Between 2012 and 2014 we posted a number of articles on contemporary affairs without giving them volume and issue numbers or dates. Often the date can be determined from internal evidence in the article, but sometimes not. We have decided retrospectively to list all of them as Volume 10, Issue 54 with a date of 2012 with the understanding that all were published between 2012 and 2014.

Maki Sunagawa and Daniel Broudy

The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 44, No. 4, November 10, 2014

Introduction

In recent years in Okinawa, local citizens have been divided over the issue of Henoko as an appropriate location for a particular kind of development. The United States military has, since the mid-1960s, been mapping out designs for a comprehensive facility for the U.S. Marine Corps at Henoko in Northern Okinawa. According to archived documents uncovered by Makishi Yoshikazu (真喜志好一),[1] the proposed military development of this region of the main island has been debated for decades and, like a vampire, time and again keeps returning from a long sleep to make its presence felt in public discourse.

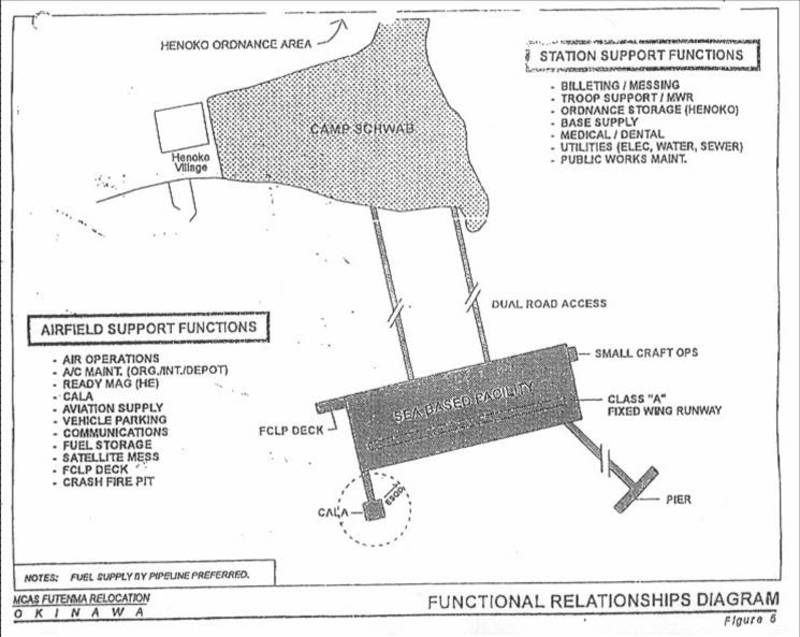

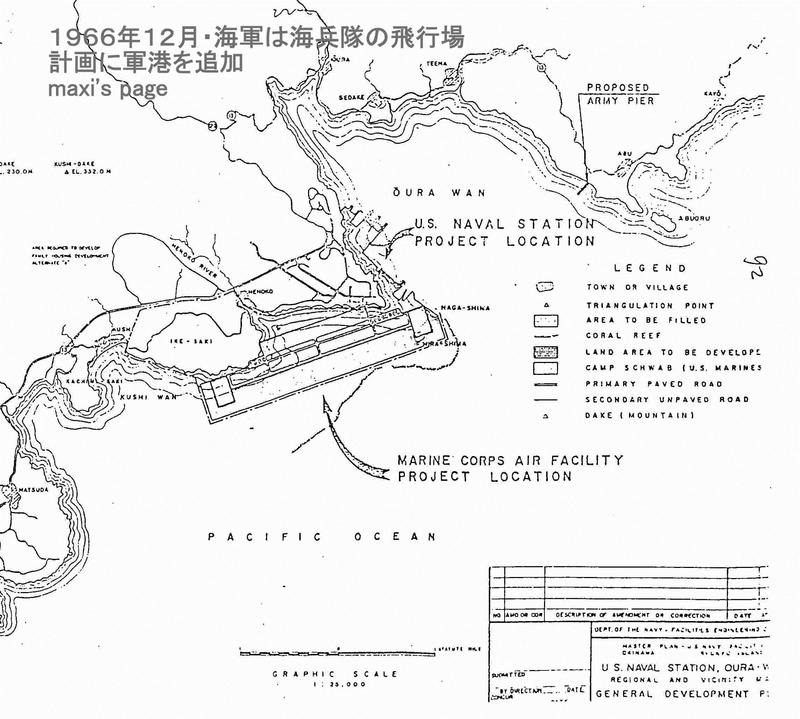

The accompanying images, featuring two distinct blueprints from the Vietnam era, illustrate the nature of the designs, as US forces have sought to establish a military air station on the coral reef system adjacent to Camp Schwab.

Of course, this kind of development is not only against the law, according to anthropologist Yoshikawa Hideki (2014),[2] but also highly unethical, as it would mean the destruction of the ecosystem and a natural habitat for marine animals in the waters just off the coastline in this area of the main island.[3] Besides these flaws in the logic guiding Washington and Tokyo’s decisions, Yoshikawa points out that “officials [from the Department of Civil Engineering and Construction] have admitted that they have no expert knowledge or experience regarding the conservation of dugong, coral, [or] alien species.”[4] For decades, government and local citizens have weighed the issue of whether yet another U.S. military base will benefit the island against the cost of damaging more of the environment.

The issues continue to be fought out in local elections. Last year, the campaign of Nago City Mayor Inamine Susumu, whose district includes Henoko, centered on the promise to thwart Tokyo and Washington’s plan to develop Henoko for U.S. military use. Mayor Inamine overcame not only the resources mobilized by his local political opponent, he also contended well with the larger political forces associated with Governor Nakaima (who had recently betrayed the citizens of Okinawa in Tokyo) and the centers of economic and political power in Tokyo and Washington. Nakaima, it will be recalled, had run his own earlier gubernatorial campaign on the pledge that he would never accept the planned base at Henoko.

But with Tokyo and Washington moving ahead with plans for the base, Mayor Inamine decided to take the anti-base case to Washington and New York. Inamine’s visit from May 18-24, 2014 was both pragmatic and symbolic. He was able to express, in person, the grievances of the local people that the long occupation of Okinawan land by U.S. military forces has created. The trip provided an opportunity to challenge the Okinawa Governor who had handed Tokyo and Washington a much-coveted Christmas gift on December 25, 2013 — official permission to begin construction of the new U.S. military facility.[5] This article examines and critiques the symbols used by the political forces in Naha, Tokyo and Washington supporting base expansion to control the meanings of key terms in the debate[6] (i.e. development), and discusses the continuing struggle to shape the outcome.

Local citizens, and members of the occupying military forces, routinely see the ever-present symbol of the prefecture, largely in public places, in television media, and in official written discourse. It is simple and elegant. The white circle represents the Roman character “o” (standing for Okinawa) while the outer red circle represents the surrounding ocean, and the inner solid circle represents peace, harmony, and development within the larger global context. One can hardly mistake the importance of the meanings expressed in the prefecture’s symbol. When it appears in official communications, citizens know that the communication carries the authority of the government. It is startling that in a democracy so few citizens challenge the uses of the symbol which allows those in political power to manipulate public opinion on issues as pressing as the proposed destruction of Henoko Bay.

Local citizens, and members of the occupying military forces, routinely see the ever-present symbol of the prefecture, largely in public places, in television media, and in official written discourse. It is simple and elegant. The white circle represents the Roman character “o” (standing for Okinawa) while the outer red circle represents the surrounding ocean, and the inner solid circle represents peace, harmony, and development within the larger global context. One can hardly mistake the importance of the meanings expressed in the prefecture’s symbol. When it appears in official communications, citizens know that the communication carries the authority of the government. It is startling that in a democracy so few citizens challenge the uses of the symbol which allows those in political power to manipulate public opinion on issues as pressing as the proposed destruction of Henoko Bay.

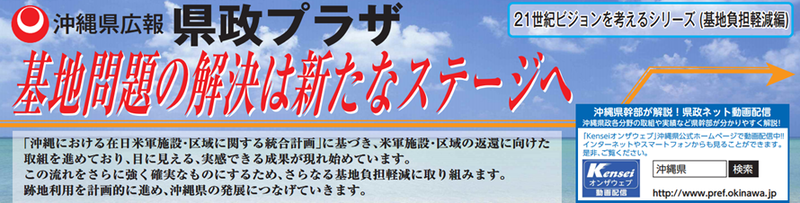

The following communication was recently published (October 5, 2014) in the Ryukyu Shimpo and The Okinawan Times, Miyako Mainichi, and Yaeyama Mainichi by the Okinawan Government Planning Office (企画推進課), American Military Affairs Office, and Community Security Policy Office (地域安全政策課). The top portion features the ubiquitous symbol for the prefecture connoting its official status with accompanying (kanji) characters for Okinawa and public relations (広報). In bold black, next to the name of the official office is the title of the communication, a definition of what is being proposed, which is a “Prefectural Government Plaza” (県政プラザ). “Plaza,” cast in Japanese katakana, connotes the positive images of the European concept of a public space where citizens are free to meet. The subtitle in bold red, just below the black bold title, combining kanji and kana, proclaims a “new stage” in the military base “solution.” The katakana evoke positive developments that represent a literal “step up” from previous societal lows. The feeling is that when people can finally accept the Henoko plan, we can all move forward together. The “21st Century Vision” that the present government is putting forward represents a great “relief” as the name connotes an ability of the government to strategically shape the future.

The central message in the text below the gold line calls attention to the local government’s hard work in solving the Futenma base issue through productive dialogues with Tokyo and with U.S. military authorities. They promise to “keep working hard” to secure “liability relief” from the central government, and in order to maintain positive forward momentum. The strategy is to keep the audience focused on the visible problem of Futenma MCAS, that dangerous eyesore in the center of densely populated Ginowan City, which is slated to be closed once the Henoko Base is constructed.

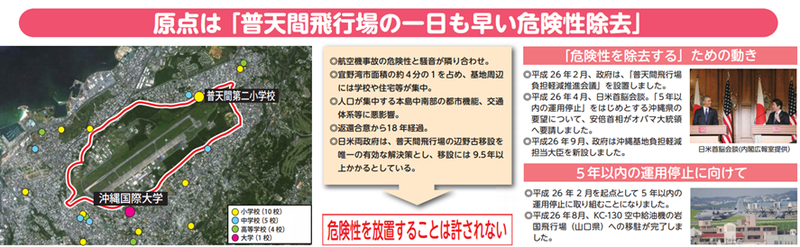

In the following section of the advertisement, readers are greeted with an array of images and textual information. The headline in white, with pink background, invites readers to contemplate a future when they can realize fast (早い) relief from the ever-present dangers (危険性) of Futenma. The kanji for “fast” reinforces the necessity for taxpayers to act quickly, much like an infomercial for Ginsu Knives featuring a “valuable” cutting board for those who “order now.”

In the following section of the advertisement, readers are greeted with an array of images and textual information. The headline in white, with pink background, invites readers to contemplate a future when they can realize fast (早い) relief from the ever-present dangers (危険性) of Futenma. The kanji for “fast” reinforces the necessity for taxpayers to act quickly, much like an infomercial for Ginsu Knives featuring a “valuable” cutting board for those who “order now.”

The aerial image of Futenma MCAS features a red border (connoting danger) outlining the base and a legend corresponding to the various schools in close proximity to this danger zone. No one who has lived in Okinawa for any length of time, especially in Ginowan City, can fail to recognize the great dangers that exist for people who live and work in communities crowded around this base. The image and its mockup of school danger zones reinforces a long-understood reality but presents it as some fresh government insight that we should, as citizens, be happy to be apprised of. And grateful to a caring government.

To the right of the image, an explanation box outlines five main points: a) we live with daily aircraft noise and under threat of a potential plane crash in our communities; b) the base occupies one quarter of the city while the surrounding areas just outside the base hold many schools and residences; c) the base creates negative effects on civic functions and transportation in such a densely-populated area; d) eighteen years have already passed since Washington agreed to return the land; and e) both the Japanese and American governments insist that relocation of Futenma base to Henoko is the only available solution and that the process of constructing Henoko and removing Futenma will require more than nine years. Having reflected on the first four points, presented as new information, readers see the fifth presented in the strict terms of black and white as the government’s one and only plan for solving the problems.

Zero alternatives are entertained, and this conclusion for the urgent problem is further reinforced in the box featuring a message in red pointing to the only way forward. On the right, the image of President Obama and Prime Minister Abe calls attention to their hard work to come to a reasonable agreement featuring details of three high-level meetings in February, April, and September of 2014. The first meeting resulted in significant progress in the development of “Futenma Airbase Burden Relief Promotion Committee,” a taskforce needed to show citizens that both governments are fully committed to relieving Okinawans of the Futenma burden. At the second meeting in April Prime Minister Abe asked President Obama to work to have Futenma closed within five years. The final meeting in September showed even greater progress when a new government minister was appointed to head the “Burden Relief Committee.”

The final image is a view of Futenma MCAS featuring a KC130 taxiing to the runway. Readers wondering what kind of work has already been done to move the Futenma base learn that an unknown number of KC130s have already been relocated to Iwakuni Air Station on mainland Japan in August 2014. It remains unclear, though, whether the aircraft have been permanently moved.

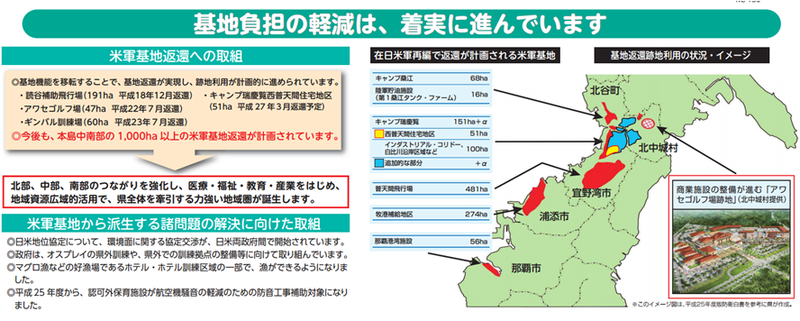

In the following section of the advertisement, the color green predominates. The positive images of a green environment flood the imagination as we read about the “burden removal that is moving forward” (基地負担の軽減は、着実に進んでいます). A green map of central Okinawa depicts the troubling US bases scattered across the land from Naha City to Chatan Town. The bases, depicted in red splotches, are singled out as areas that will be returned once the new Henoko base is completed, turning the populous central and southern areas green. To reinforce the value of building the Henoko base which will destroy the natural bounty of Oura Bay, citizens learn that they can look forward to yet another massive shopping mall, with accompanying industrial facilities, on land once long occupied by a military golf course. Worth noting is that this region, known for its extremely rich soil, was, before its theft from local farmers, producing some of the island’s richest crop harvests. The artist’s rendering of a new business development surrounded by greenery evokes many positive images of a time when this area was rich with nature itself.

The textual information reinforcing the map points to a hopeful future when the southern region of the island and the northern region can be more closely linked as the bases that effectively divide the island and severely hamper travel disappear. As with the preceding section, the box of text points an arrow downward to the only logical conclusion that readers are compelled to draw: if we can strengthen the geographical links between northern, central, and southern Okinawa, we can enjoy a new and more tightly knit prefecture born of our collective efforts.

In the final part of this ad, readers are shown a future free from bases in areas from Chatan Town to Naha City. They can also see another artist’s concept of land once occupied by Futenma as tree-lined streets bound by a light rail system that cuts a path directly through the old airstrip. The old asphalt tarmac, concrete flight line, and steel hangers give way to new apartment buildings, houses, and shopping areas. Local school children, from elementary and junior high, were also enlisted in the effort to put an innocent spin on the hopes of the future with submissions of art work that imagined a future without the presence of the Futenma base.

The three central points conveyed in the header communicate the idea that the investment for developing the land is imperative to bringing Okinawa into a brighter future and that the government’s plan lays the groundwork for this future. These points also emphasize that government leaders will also pay close attention to citizens’ opinions about the direction of development for Okinawa as a whole. The cruelest irony is that the government has ignored the opinions of citizens about the “development” of Henoko.

Conclusion

In his 1999 article, “US as Global Overlord,” Herbert Schiller notes that one of the most tested and effective ways of maintaining order in society is to control the meanings of important words, which can be accomplished through power and access to powerful forms of media. Schiller calls this society’s “informational infrastructure,” which the elite use to create (and recreate) and circulate “the governor’s view of reality.”[7] In the case of Okinawa, we are all confronted with a governor who can easily draw upon the forces of the informational infrastructure at his disposal and advance his narrow view of development for the people and the land.

The signs, symbols and textual information analyzed in this local government propaganda point to spaces, land areas, and imagined communities in the future that develop, oddly, from the destruction of these present places. The voices of the public that have called for a return to democracy are being drowned out by calls for militarily-driven ‘development’ at all costs — notably at the expense of the environment threatened by a huge reclamation project. The impending decision in the political race for the governor’s seat in Okinawa’s November 16 election, has powerful consequences for environmental destruction which are being concealed by pervasive myths of future economic development. If Schiller was right about the power that Governors hold over the meanings of key words, how might we as citizens develop independently beyond this narrow view presently offered to us?

Perhaps, as with Nago City, where popular anger saw the tenure of Susumu Inamine renewed, it remains possible to hope that the island-wide campaign of resistance to military base expansion at the expense of the environment will prevail against the present Governor. A recent political rally for Onaga Takeshi, campaigning against the base, brought out fifteen thousand citizens who are neither fooled or intimidated by the official propaganda. At this writing, despite the pro-base propaganda discussed here, and a wealth of other forms not mentioned, Onaga appears to be on his way to the Governorship.

Maki Sunagawa is a first-year researcher in the Graduate School of Intercultural Communication at Okinawa Christian University where she is taking up studies in social semiotics and the signs for development that prevail in public relations literature. She is presently working towards a graduate qualification focused on the McDonaldization of Okinawan culture influenced by long-standing conditions of foreign occupation.

Daniel Broudy is Professor of Rhetoric and Applied Linguistics at Okinawa Christian University. He has taught in the United States, Korea, and Japan. His research includes the critical analysis of media discourse, signs, and symbols. He is co-author of Rhetorical Rape: The Verbal Violations of the Punditocracy (2010), serves as a managing editor for Synaesthesia communications journal, and writes about current discourse practices that shape the public mind. He is the co-editor to Under Occupation: Resistance and Struggle in a Militarised Asia-Pacific.

Notes

[1] For further details, please visit: http://www.ryukyu.ne.jp/~maxi/

[2] Hideki Yoshikawa, “An Appeal from Okinawa to the US Congress: Futenma Marine Base Relocation and its Environmental Impact: U.S. Responsibility,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 39, No. 4, September 29, 2014

[3] According to a complaint lodged in United States District Court for the Northern District of California, San Francisco Division, “This plan would destroy the most important remaining habitat of the Okinawa dugong, a genetically isolated and unique population of dugong (a marine mammal) and a protected cultural property under the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA)” (2014 p. 2).

[4] Yoshikawa, op. cit.

[5] For further details, please visit: http://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/96_abe/actions/201312/25mendan.html

[6] Herbert Schiller “US as global overlord: Dumbing down, American-style” Le Monde Diplomatique, August 1999.

[7] Schiller, Ibid.

Asia-Pacific Journal articles on related subjects –

Hideki Yoshikawa, An Appeal from Okinawa to the US Congress

Gavan McCormack and Urashima Etsuko, Okinawa’s Darkest Year

Jon Mitchell, Nuchi Du Takara, Okinawan Resistance and the Battle for Henoko Bay