US Shadow over China-Russia Ties

By M K Bhadrakumar

[In recent weeks Japan Focus has highlighted tensions in the US-China relationship, notably Richard Tanter’s account of The New American-led Security Architecture in the Asia Pacific and Paul Rogers’ The United States, China and Africa. M K Bhadrakumar’s geostrategic analysis approaches the issues from an alternative perspective which highlights the weakness of the China-Russia relationship, and a comprehensive deepening of US-China ties.

On March 22, even as Chinese President Hu Jintao was preparing to leave on a state visit to

Chinese President Hu Jintao attends the welcoming

ceremony hosted by US President Bush, April 2006.

But no less lacking in political symbolism was the immaculate timing of the announcement by US computer-chip giant Intel on Monday, even as Hu was arriving in Moscow, that it would build a US$2.5 billion semi-conductor plant in Dalian, China’s northeastern port city.

If timing has a place and meaning in diplomacy, the two developments in

In

Indeed, no sooner than Hu concluded the last leg of his visit to

Bush would have noted that the exhaustive Russia-China joint statement issued in

The Kremlin also seems to realize the limits to the Russia-China strategic partnership by choosing to release in

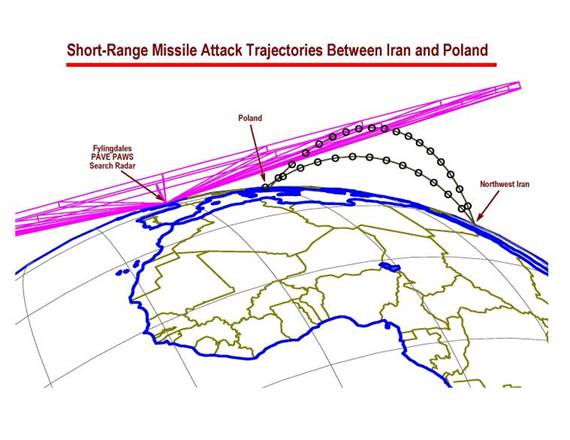

On the missile-defense controversy, the Russian foreign-policy document says, “The appearance of a

Energy cooperation

Arguably, Hu’s state visit to

But even then there wasn’t much to showcase. An energy deal for increased Russian supplies by 3 million tons of oil to

But for reasons unclear, the signing of the agreement was put off “indefinitely” at the last minute. Energy cooperation was thought to be a core sector of the Russia-China strategic partnership. Is it becoming a raw nerve?

A Chinese commentator noted, “From the perspective of energy security, European countries should diversify energy import channels and expand imports from the

Obstacles in the strategic partnership

Hu told the Russian media ahead of his visit to

Chinese media reported that Hu made “several proposals” in the direction of enhancing the two countries’ strategic partnership. First, Hu told Putin, both countries should become “sincere political partners of mutual trust”. Second, they must view their bilateral relationship as a “priority in each other’s foreign policy”. Third, they must “enhance support on issues concerning each other’s core interests”.

Fourth, mutual benefit and a long-term perspective must characterize their economic cooperation. Fifth, Hu stressed that the two countries should “help each other in security cooperation, strengthen strategic security cooperation … push forward security cooperation within the framework of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, maintain regional security and stability”.

Finally, Hu proposed,

But Hu sidestepped the central issue that lies right across the path of the China-Russia strategic partnership, which is that Moscow is watching with dismay as China shifts gear to a more mature, confident and predictable relationship with the United States at a juncture when Russia’s own relations with the US have plunged to their lowest level in the post-Cold War era and are possibly in a state of deep chill.

Without doubt,

But there is a world of difference between the respective approaches of

Besides, the core issue with regard to

On balance,

The researcher audaciously went on to speculate on the efficacy of a Group of Two to replace the largely ineffectual Group of Eight. “Indeed, the Chinese and US economies, as the twin engines powering the world economy, are supposed to shoulder more responsibilities for setting the ‘roadmap’ and ‘traffic rules’ for the development of the global economy and trade,” he argued.

US-China relations forge ahead

Commenting on the first session of the Sino-US strategic economic dialogue in Beijing last December, Yuan Peng, a leading Chinese scholar specializing in US-China relations, wrote that Bush’s dispatch of a dozen or so officials of cabinet rank to the summit implied that “Sino-US relations have stabilized and have moved forward”, and that the two countries have equally become “responsible stakeholders” in the relationship.

Again, a senior researcher with the

Interestingly, a senior Chinese diplomat, Wang Yusheng, writing in the official China Daily, adopted a patronizing attitude toward Putin’s speech. Wang noted that US officials shrugged off Putin’s “stinging broadside … indicating that the

Wang commented with icy objectivity that “it is very hard to reconcile the two countries’ [US and

A recent article in the China Daily dwelt at length on the nature of big-power politics in the post-Cold War era. It said bilateral ties are “healthy” when no third country is targeted and when the “imperative” is kept in view that a country primarily secures its own national interests while respecting those of others. Thus, “There will be competition alongside cooperation and conflicts alongside compromises. Cooperation must be based on sincerity and trust while compromise should be appropriate and disputes should never be allowed to grow into confrontation.” From this perspective, the newspaper described China-Russia relations as “a harmonious relationship with unique characteristics”.

“The two countries [

The wrangling that lies ahead in Russia-China relations can be kept to a minimum if the two countries get used to their divergent foreign-policy priorities. Fortunately for them, as the China Daily assessed recently, their relationship has “more positive than negative factors”.

M K Bhadrakumar served as a career diplomat in the Indian Foreign Service for more than 29 years, with postings including ambassador to

This article originally appeared on Asia Times on Mar. 31, 2007. Posted at