Between 2012 and 2014 we posted a number of articles on contemporary affairs without giving them volume and issue numbers or dates. Often the date can be determined from internal evidence in the article, but sometimes not. We have decided retrospectively to list all of them as Volume 10, Issue 54 with a date of 2012 with the understanding that all were published between 2012 and 2014.

Sakamoto Junji with an introduction by Linda Hoaglund

Introduction

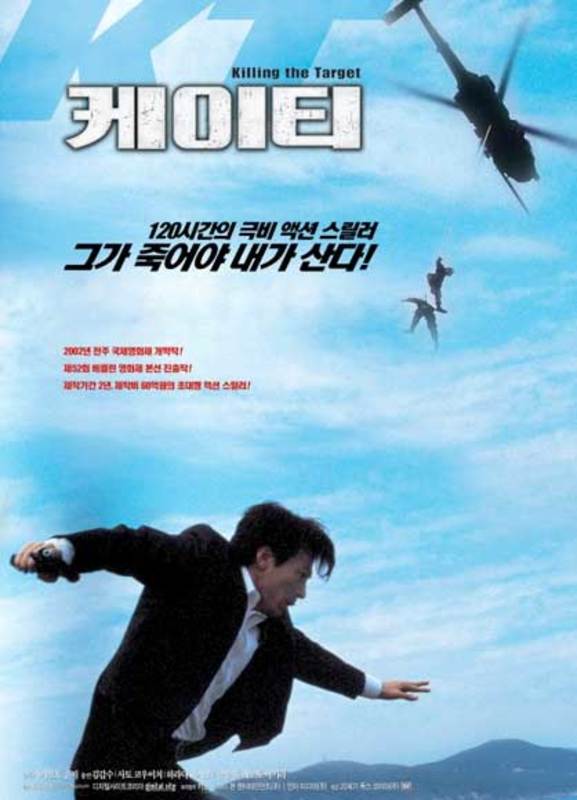

When Sakamoto Junji, the veteran film director, wrote in Asahi about the recently passed state secrets act, he referred to KT, his film invited to compete in the Berlin Film Festival in 2002. KT is a political thriller based on the 1973 kidnapping of Kim Dae-jung from a Tokyo hotel. At the time Kim was a South Korean legislator, dissident, and an outspoken critic of South Korea’s military dictatorship and the abduction caused an international furor at the upper reaches of the Japanese, South Korean and U.S. governments. Five days later, Kim mysteriously reappeared in Seoul; blindfolded, wounded and dazed.

Twenty-five years later, Kim was elected President of a democratic South Korea and on the eve of his inauguration the Korean government finally disclosed the Korean CIA’s role in the kidnapping. In his fictionalized account, Sakamoto speculated that the Japanese Self Defense Forces had also been covertly involved. The gripping film, featuring a sizzling score by Hotei Tomoyasu (Japan’s most famous guitarist), is now available for streaming on Netflix and finally eligible for the international audience it deserves outside of Japan. The creative courage that drove Sakamoto to peer into the dark side of Japan’s relationship with Korea a decade ago compels him today to speak out about the perils of the state secrets act.

Sakamoto Junji

Sakamoto’s article from the Asahi Newspaper 12/24/13

“A secret unit of Japan’s Self Defense Forces was involved in the kidnapping of Kim Dae-jung (now deceased), former president of South Korea, from his hotel in Tokyo in 1973… That was the fictional premise of KT, the film released in 2002 that I directed.

I researched still classified documents and approached people who knew the secrets to interview them. I used fiction to close in on the facts of that kidnapping, whose investigation had been politically terminated in order to shroud them in darkness. Even before we rolled the camera, a stranger began staking out my home and my producer received phone calls from someone demanding to read the script. My guts told me we were encroaching on areas that those in power did not want touched.

KT

As filmmakers, it’s our job to shed light on buried facts, drag them out into public view and burn them onto film. But from now on, those involved will refuse to speak for fear of being judged by the law and we will no longer be able to give birth to films whose themes are classified. I myself might be arrested.

When a nation determines its policies, it must study the historical record. If the mistakes of those in power are made secret, we can no longer even investigate them. The State Secrets Act should be abolished and we the people should start over from scratch and debate the issue.

The ruling party repeatedly forced votes on the “Secrets” act. Ironically, I think this was good. Their strong-arm tactics sparked rage in people’s hearts. We the people will not allow the government or the ruling party to run amuck on the issues of “exercising the right to collective self defense” and revising the constitution. We the people also have the right to dismiss the ruling party.”

Because I had subtitled KT into English, I was asked to accompany Sakamoto to Berlin to interpret for him. One question he was frequently asked by international journalists was, “Why a film about this subject, now?” I remember him responding, “Since 2000, Korean television dramas have become the darlings of Japanese TV audiences and later this year, Japan and Korea will jointly host the World Cup soccer games. My Korean-Japanese producer and I agree that now is the time to depict the historical causes of the tensions that still fester beneath the amity between the two countries.” Reviewing my computer files about KT, I came across the Director’s statement Sakamoto had written for the international press kit. I quote from it here as it feels all too relevant a decade later.

From the director’s statement for the Berlin Film Festival 2002

“… In 1972, as I watched tanks take control of Seoul under Martial Law, I concluded, “Thank God I wasn’t born in Korea. That country’s in greater peril than even Japan.” Although it was not taught in school, I instinctively grasped that Japan was somehow complicit in Korea’s peril. The Kim Dae-jung kidnapping incident in 1973 only heightened my acute anxiety. Even as a teenager I saw right through the official resolution of the case, and knew that it had been enforced by those who maneuver behind the scenes, in the shadows of Japan and Korea.

I decided to make a film in which I would approach a nation’s history as if it belonged to a character, setting my sites on Korea, our closest neighbor. There, I discovered the dark void I had always sensed, but purposefully ignored. Staring into that void took courage, but I had come too far.”

Translated with the permission of Sakamoto Junji by Linda Hoaglund, Director

ANPO: Art X War

Things Left Behind

Recommended citation: Sakamoto Junji introduced and translated by Linda Hoaglund,