Internment Without Charges: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment

By Linda Gordon

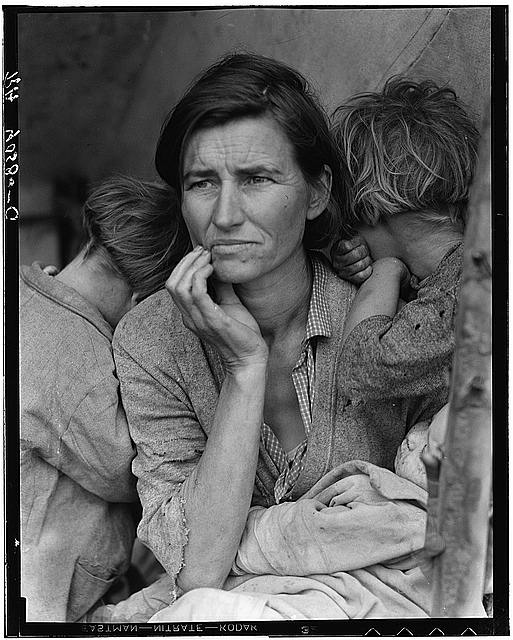

In 1942 the U.S. War Relocation Authority hired documentary photographer Dorothea Lange to photograph the World War II internment of approximately 120,000 Japanese Americans. Lange is now a world-famous documentary photographer, best known for chronicling the Great Depression of the 1930s. Her work is the subject of more than a dozen glossy art books. Even those who do not know her name will recognize some of her pictures. One of her photographs has been called the most famous image in the U.S.

Photograph known as “Migrant Mother”

In October 2005 her photograph of the “White Angel Bread Line” sold at auction for $822,400, at that time the second highest price ever paid for a photograph.

Between February and July 1942 Lange worked assiduously to cover the internment throughout California. She made more than 800 photographs. But some military authority found them so evidently critical that the photographs were impounded for the duration of the war. Afterwards they were quietly placed in the U.S. National Archives where, because they are government property, they are in the public domain—free to be used by anyone for any purpose whatsoever.

A few scholars have published a small number of the photographs—fewer than six, to my knowledge—but they have never been published or exhibited as a group. This is surprising, given Lange’s reputation, and the fact that the U.S. government officially apologized for the unjustified and racist internment of 120,000 Japanese Americans. A selection of these photographs, approximately one-eighth of the total, are now published for the first time in Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment (Norton, 2006), edited by Linda Gordon and Gary Y. Okihiro. A selection of Lange’s images, and the captions she wrote to accompany them, are also displayed below.

Lange’s photographic critique is especially impressive given the political mood of her time—early 1942, just after Imperial Japan bombed Pearl Harbor, destroying a substantial portion of the American Pacific fleet. American anger was especially strong because most did not know how deliberately President Roosevelt, eager to help the British, had provoked the Japanese. But this anger was soon organized from above to focus not only on the treacherous Japanese attack, ignoring the historical context of U.S.-Japan conflict in Asia, and the nature of Japanese colonialism, but on the Japanese as a race. Anti-Japanese racism was already well developed on the west coast, and after the attack it was ratcheted up by politicians and the press; after rumors surfaced of plans to intern Japanese Americans, big agribusiness interests joined in the barrage of defamation, probably because they thought (correctly) that they could buy Japanese farms at discounted prices. Now the pejorative verbal and visual rhetoric about Japanese Americans was intensified and expanded to include completely uncorroborated allegations of disloyalty and treason.

Hysterical waves of fear of further Japanese attacks on the west coast of the U.S. crested on a century of racism against East Asians. Rumors of spies, sabotage, and attacks circulated widely. A few authenticated Japanese attacks—for example, in February 1942 submarines shelled a Santa Barbara oil refinery; in June a submarine shelled the Oregon coast; in September a submarine launched incendiary bombs near Brookings, Oregon—escalated the fear-driven hysteria, although no one was hurt, damage was minimal, and the Japanese American community was not implicated. But significantly, the order calling for the internment preceded these attacks. Military leaders especially ratcheted up the anti-Japanese fever. General John DeWitt, head of the U.S. Army’s Western Defense Command, opined that “the Japanese race is an enemy race and while many second and third generation Japanese born on American soil, possessed of American citizenship, have become ‘Americanized,’ the racial strains are undiluted …. The very fact that no sabotage has taken place to date is a disturbing and confirming indication that such action will be taken …” That kind of hysterical illogic went largely unchallenged. As the Los Angeles Times justified the policy, “A viper is nonetheless a viper wherever the egg is hatched …”

In this situation, as the writer Carey McWilliams remarked, you could count on your fingers the number of “whites” who spoke publicly against sending Japanese Americans to internment camps. Liberals and leftists, even those who explicitly opposed racism, remained silent because they swallowed the claim that this was a necessary measure to defeat the Nazi-Japanese-Italian alliance—a claim made by their beloved President Roosevelt. The Communist Party was then willing to accept any policy that purported to aid the Soviet resistance to the Nazi invasion. Even the liberal Dr. Seuss contributed a racist anti-Japanese cartoon.

In February 1942 FDR ordered the internment of the Japanese Americans, regardless of their citizenship, and the War Relocation Authority (WRA) was established on March 18 to organize their removal. These prisoners were never even charged with a crime, let alone convicted. Two-thirds of them were U.S. citizens, born in the U.S.—the remainder could not have become citizens because at that time people of Asian origin were prohibited from naturalization. The WRA was then headed by Milton Eisenhower (brother of Dwight), who had previously worked for the Department of Agriculture; he might well have been acquainted with Paul Taylor (Lange’s husband), and Lange’s reputation as a documentary photographer for the Farm Security Administration had probably reached him. Equally important, no doubt, Lange lived in San Francisco, a major center of the Japanese American population. Still, her hiring was ironic. No doubt she had received an enthusiastic recommendation because her work had so perfectly advanced the earlier agency’s agenda of documenting rural poverty. The WRA probably expected the same compliance now but did not get it.

Another question arises: Why did the WRA want photographic documentation of the internment? Paul Taylor thought that making a photographic documentary record was by then was simply “the thing to do” in government. Another factor: “government” was by no means of one mind—if the Army’s Western Command, which ran the evacuation and the camps, had been in charge, there might not have been any photographs. A photographic record could protect against false allegations of mistreatment and violations of international law, but it carried the risk, of course, of documenting actual mistreatment. (A measure of how important it seemed to prevent such a calamity was that the internees were forbidden to have cameras.)

Lange was already opposed to the internment when offered the job documenting it. She had several Japanese American acquaintances, mainly through Taylor, a maverick progressive economics professor at U.C. Berkeley who mentored several Japanese American graduate students. Taylor was one of the very small group of Anglos who protested Executive Order 9066 ordering the evacuation. Both Lange and Taylor had been active in the struggles of migrant farmworkers, who were primarily Mexican, and this engagement had made them acutely aware of racism west-coast style.

Nevertheless, what Lange saw was worse than she had expected. Every stage she observed—the peremptory directives to Japanese Americans to “report,” the registration, the evacuation, the temporary assembly centers and the long-term internment camps—deepened her outrage. This in turn increased her determination to finish the job and capture the actual conditions, and doing so required withstanding considerable adversity. She worked nonstop 16-hour days for half a year, driving north, south and east many miles through California’s agricultural valleys where most Japanese Americans lived. She traveled on roads that were far from superhighways in cars not air-conditioned despite the scorching heat that prevailed toward the end of her undertaking. She did this as a disabled woman already beginning to feel the pain of bleeding ulcers and the muscular weakness we now know as post-polio syndrome. She patiently faced down continual harassment from army officers and guards who threw at her any regulation or security claim they could think of to prevent, slow, or censor her work. She was away from home for most of 5 months, worrying constantly about her older son, who at age 17 was rebelling to the extent of being called a juvenile delinquent. She undertook to photograph something she considered odious in order to create this record. She steeled herself to witness suffering. She compromised some of her most tenaciously held photographic and aesthetic values in order to record everything she could.

Not least among her difficulties, she maintained a facade of neutrality in her dealings with army brass so that they wouldn’t fire her. This was a close call. Lange developed a particularly adversarial relation with Major Beasley (referred to by some as Bozo Beasley), who tried to catch her in various infractions. Once she gave a photograph to Caleb Foote, a leader in the Fellowship of Reconciliation, who used it as the cover of a pamphlet denouncing the internment. Beasley thought he had her. But luckily for Lange, a congressional investigating committee had published the picture, thus putting it into the public domain. Another time Beasley thought he had caught her out in holding back a negative but when he called her in and demanded that she produce the missing negative, she showed him that it was filed just where it ought to have been.

I believe that she imagined her photographs producing a narrative, because by this time she had become convinced that pictures communicated best when telling a story. In doing this she went far beyond her assignment—making, for example, scores of images of the lives and contributions of Japanese Americans before the Executive Order. So in designing this book, Gary Okihiro and I arranged the photographs not in the order she took them—because the internment process was in different stages in different parts of California—but in the order I believe she would have wanted: tracing the experience of the Japanese Americans from life prior to the evacuation order through the relocation and the internment experience.

The before-evacuation photographs emphasized the respectability and American-ness of the Japanese Americans and the ironies of their internment.

(Please scroll down; Lange’s photos are large to show detail. Captions for all numbered photos are as recorded in the National Archives.)

536053: San Francisco, California. Flag of allegiance pledge at Raphael Weill Public School, Geary and Buchanan Streets. Children in families of Japanese ancestry were evacuated with their parents and will be housed for the duration in War Relocation Authority centers where facilities will be provided for them to continue their education.

536474: Florin, Sacramento County, California. A soldier and his mother in a strawberry field. The soldier, age 23, volunteered July 10, 1941, and is stationed at Camp Leonard Wood, Missouri. He was furloughed to help his mother and family prepare for their evacuation. He is the youngest of six years children, two of them volunteers in United States Army. The mother, age 53, came from Japan 37 years ago. Her husband died 21 years ago, leaving her to raise six children. She worked in a strawbery basket factory until last year when her her children leased three acres of strawberries “so she wouldn’t have to work for somebody else”. The family is Buddhist. This is her youngest son. Her second son is in the army stationed at Fort Bliss. 453 families are to be evacuated from this area.

537475: Mountain View, California. Scene at Santa Clara home of the Shibuya family who raised select chrysanthemums for eastern markets. Madoka Shibuya (right), 25, was a student at Stanford Medical School when this picture was taken on April 18, 1942. Evacuees of Japanese ancestry will be housed in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration.

As the round-up proceeded, the photographs show people ripped from their lives on short notice, forced to sell property at great losses, to give up homes and furnishings, leave jobs and schools; lined up, registered, tagged like packages; waiting, waiting, often guarded by armed soldiers; allowed to bring only what they could carry. Lange frequently used her unequaled mastery as a portrait photographer.

537773: Byron, California. Field laborers of Japanese ancestry from a large delta ranch have assembled at Wartime Civil Control Administration station to receive instructions for evacuation which is to be effective in three days under Civilian Exclusion Order Number 24. They are arguing together about whether or not they should return to the ranch to work for the remaining five days or whether they shall spend that time on their personal affairs.

537745: 2031 Bush Street, San Francisco, California. Friends and neighbors congregate to bid farewell, though not for long, to their friends who are enroute to the Tanforan Assembly center. They, themselves will be evacuated within three days.

It is in the close-ups that we sense that the greatest injury was often the humiliation.

537566: Centerville, California. A grandfather awaits evacuation bus. Evacuees of Japanese ancestry will be housed in War Relocation Authority centers for the duration.

The temporary assembly centers were degrading beyond imagining. At the Tanforan assembly center in San Bruno, a former racetrack, the internees lived in former horse stables.

537930: San Bruno, California. Near view of horse-stall, left from the days when what is now Tanforan Assembly center, was the famous Tanforan Race Track. Most of these stalls have been converted into family living quarters for Japanese.

They are surrounded by prison regulations: no cameras, no books or magazines in Japanese, meals in large mess halls with food often ladled out from garbage cans, collective toilets, whole families sleeping in one “room” barely partitioned off from adjoining families, singles sleeping in huge wards with long rows of cots.

537924: San Bruno, California. “Supper time” Meal times are the big events of the day at assembly centers. This is a line-up of evacuees waiting for the “B” shift at 5:45 pm. They carry with them their own dishes and cutlery in bags to protect them from the dust. They, themselves, individually wash their own dishes after each meal because dish washing facilities in the mess halls proved inadequate. Most of the residents prefer this second shift because sometimes they get second helpings, but the shifts are rotated each week. There are eighteen mess halls that together accommodate 8,000 persons for three meals a day. All food is prepared and served by evacuees. The poster seen in the background advertises the candidacy of Mr. Suzuki for this precinct.

We realize now that she has forged a theme, both visual and emotional, that winds through her photographs: waiting in line. The internees line up for their preliminary registration, they wait in chairs, they stand waiting before tables at which officials ask questions, fill out forms, give out instructions. Then they wait for buses or trains to carry them away. They wait in line for meals, for bathrooms, for laundry sinks.

537941: San Bruno, California. Many evacuees suffer from lack of their accustomed activity. The attitude of the man shown in this photograph is typical of the residents in assembly centers, and because there is not much to do and not enough work available, they mill around, they visit, they stroll and they linger to while away the hours.

They suffer acutely from idleness, having been deprived of work, school, avocation, community—and freedom.

Manzanar was the only long-term internment camp Lange was able to visit. The snow-covered Sierras looking down from the east did nothing to cool the 100-degree-plus heat, and there were neither trees nor hills to break the fierce winds, whether icy or hot. Lange was awed by the hostile environment: “meanest dust storms … and not a blade of grass. And the springs are so cruel; when those people arrived there they couldn’t keep the tarpaper on the shacks.” Unlike the other camps, Manzanar needed no high barbed fence or guards—as with Alcatraz, geography formed the prison walls.

539961: Original caption: Manzanar, California. Dust storm at this War Relocation Authority center where evacuees of Japanese ancestry are spending the duration.

Here they settle in and recreate a life.

538152: Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. William Katsuki, former professional landscape gardener for large estates in Southern California, demonstrates his skill and ingenuity in creating from materials close at hand, a desert garden alongside his home in the barracks at this War Relocation Authority center.

537991: Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California.

Grandfather of Japanese ancestry teaching his little grandson

to walk at this War Relocation Authority center for evacuees.

537962: Manzanar Relocation Center, Manzanar, California. An elementary school

with voluntary attendance has been established with volunteer evacuee

teachers, most of whom are college graduates. No school equipment is as yet

obtainable and available tables and benches are used. However, classes are

often held in the shade of the barrack building at this War Relocation Authority

center.

I came to these photographs in the process of writing a biography of Dorothea Lange, in which I will be examining the visual culture of the depression and “New Deal,” the representation of poverty, race, and class conflict. These photographs, however, could not await the completion of the biography. Their relevance to internment-without-charges today seemed to me to require bringing them to public attention.

Dorothea Lange challenged the political culture that categorized people of Japanese ancestry as disloyal, perfidious, potentially traitorous, that stripped them of their citizenship and made them unAmerican. She wanted to stop the internment, and although she could not do that, she surely hoped that it would not be repeated. She was as eager to defeat the Axis powers as any other supporter of democracy, and worked on other photographic projects to honor those who contributed to the war effort—for example, portraits of defense industry workers. She too thought World War II was a “good war,” honorable and necessary. If her photographs of a major American act of injustice had nuanced this verdict just a bit, that fact would hardly have undermined the national commitment. And the added nuance might well have contributed to developing among Americans a capacity for more complex, critical thinking about ensuing U.S. race and foreign policy.

Photograph of Lange herself, photographing the internment

Linda Gordon is a professor of history at New York University and the author of the Bancroft Prize-winning The Great Arizona Orphan Abduction and other books dealing with the history of controversial social policies, such as birth control and protection against family violence. Gordon and Gary Y. Okihiro are the editors of the recently published Impounded: Dorothea Lange and the Censored Images of Japanese American Internment. This article was written for Japan Focus and posted on November 2, 2006.

Linda Gordon is interviewed and profiled at History News Network

For other important articles on Japanese American internment:

* See A. Wallace Tashima, “From the Internment of Japanese Americans to Guantanamo: Justice in a time of trial.”

* See Jean Miyake Downey, “Satsuki Ina’s From a Silk Cocoon, Japanese-American Incarceration Resistance Narratives, and the Post 9/11 Era.”

* See Greg Robinson, “The McCloy Memo: A New Look at Japanese American Internment.”

* See Mark Selden, “Remembering ‘The Good War’: The Atomic Bombing and the Internment of Japanese-Americans in U.S. History Textbooks.”