Exhibiting World War II in Japan and the United States

Laura Hein and Akiko Takenaka

Like most people, museum professionals generally dislike being at the center of a firestorm of criticism. Yet in recent years, many Japanese and American museum curators have suffered this fate for their exhibits on World War II. As many scholars have noted, war remembrance is fraught with difficult issues, prominently including how to portray the motives, policies, and conduct of one’s own government during the war. In both countries, curators, particularly those at public institutions, faced a sudden increase in vitriolic political criticism in the mid-1990s over how to remember the wartime past.

The controversies over exhibiting war have highlighted the relationship between museums and their audiences and the professional responsibilities of curators. Controversy has erupted most often when the target audience was young people, both in Japan and America. In the United States, museum professionals have endured fierce battles over depictions of racial minorities, including foreigners, as well as the morality of the two atomic bombs dropped on Japan. Japanese curators have struggled over whether to explain Japan’s involvement in the Asia-Pacific War as a battle of self defense or of imperial ambition, and what to say about war crimes committed in other Asian countries. Debate in both countries often has assumed that the important constituencies are all domestic, even though some of these museums are significant international tourist destinations.

There was little conflict over museum portrayals of World War II in either country until the huge battle over the National Air and Space Museum’s 1995 exhibit on the Enola Gay (the airplane used to drop the atomic bomb on Hiroshima) and a series of conservative attacks on Japanese peace museums that began in 1996. The curators at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington D.C. had originally planned to locate the Enola Gay’s historic run in the context of the war that led up to that event and also depict the destruction of the city of Hiroshima and its inhabitants using artifacts borrowed from the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. Their proposal also explored the implications of having entered the nuclear age. However, when they circulated the initial draft for comments, veterans’ groups publicly attacked these aspects of the planned exhibit as anti-American and unacceptable. In the end, the curators capitulated, and the new annex to the museum in Virginia now displays the Enola Gay without discussing the human suffering caused by its use or the ambiguous legacy of nuclear weaponry since 1945.

The Enola Gay. Like most of the images here,

this is courtesy of the U.S. National Archives

Postwar public opinion in Japan has been strongly pacifist since 1945, at least until the end of the Cold War and the death of the Showa emperor led to a major reassessment of the war years. Many older Japanese root their pacifism in personal memories of loss and suffering. In the 1990s, however, many Japanese began taking a more self-critical look at their wartime past. War remembrance soon grew more polarized over such issues as the stance of the wartime government toward its own citizens and the culpability of ordinary Japanese in mistreatment of Asians. Finally some Japanese today believe that postwar peace and prosperity was only possible because the wartime leadership was defeated and discredited, while others argue for a more positive legacy from the war years. In other words, in the 1990s in Japan the war was remobilized as an ideological site of nationalist remembrance, with one side asserting the right to an American-style militarized national identity and the other continuing to insist on a pacifist interpretation of war remembrance.

This fast changing international and domestic climate soon affected museum depictions of the war. Several cities and prefectures, including Osaka, Kawasaki, Saitama, and Kanagawa opened peace museums in the early 1990s that both critically depicted Japan’s role in the Asia-Pacific War and also preserved local Japanese memories of their own war losses, while Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and Nagasaki Prefectural Peace Museum incorporated new material critical of Japan’s war. In 1996, Japanese conservative nationalist groups, alarmed by these changes, went on a counter-offensive. These groups, such as the Liberal View of History Study Group (Jiyushugi shikan kenkyukai), led by Fujioka Nobukatsu, had earlier attacked middle-school textbooks as “self-flagellating” and sought not only to end Japanese criticism of Japan’s wars in the 1930s and 1940s but also to change public opinion in favor of future rearmament. They attacked the Nagasaki museum curators’ plan to “include in their exhibit” photographs of “the Nanjing Massacre, Unit 731 and their experiments with biological weapons, and the comfort women.” In response, the Nagasaki museum removed some of the new exhibit.[1]

So how did museums respond to these attacks on their patriotism? Japanese and American museums have deployed many of the same strategies—some effective and some self-defeating—for meeting those challenges. Neither has found ideal ways of addressing these issues, although, as we explain, some directions seem to hold greater promise than others.

War and Peace Museums

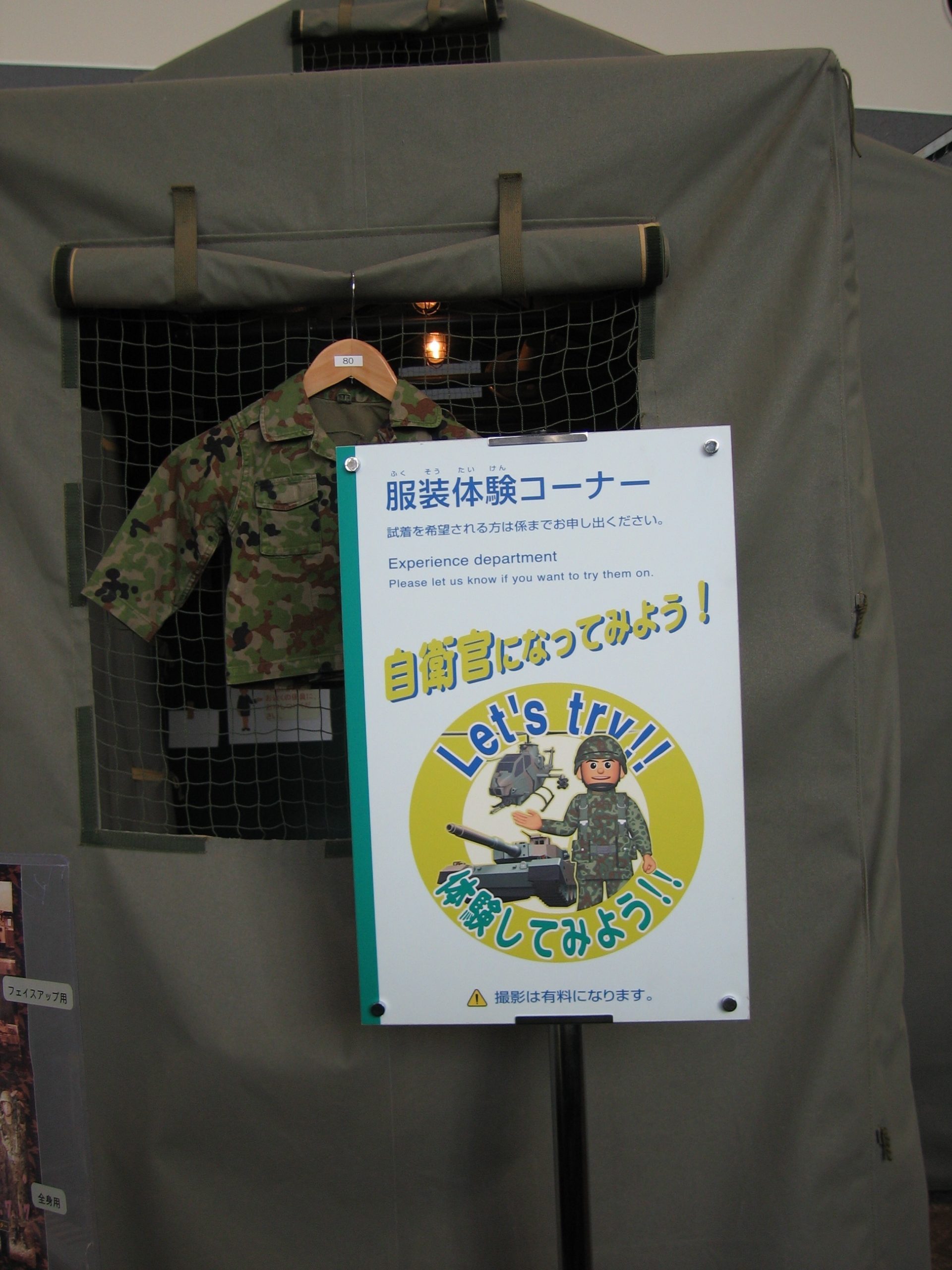

Japan is home to over two hundred museums and exhibit halls that focus on the Asia-Pacific War, and the United States has well over one hundred The stances of these museums vary considerably within each country, reflecting the highly politicized and diverse nature of war remembrance everywhere. In both nations, many museums unabashedly celebrate national military actions. In Japan, this is particularly true of those managed by the Self Defense Forces (SDF). The Army, Navy and Air Force divisions of the SDF own and operate 130 so-called Public Relations Facilities (koho shisetsu), usually inside their bases throughout Japan. Their exhibits celebrate Japan’s war in China, which started in 1931 and expanded into the Pacific in 1941. In fact, the ultimate goal of the SDF museums seems to be to create an uninterrupted celebratory history of the Japanese military from the establishment of the imperial armed forces in the late nineteenth century through today. The most popular SDF facilities include “Sail Tower” at the Sasebo base in Nagasaki and the newest: the PR Center in Asaka City, Saitama, that opened in 2002, which offers virtual experiences of war to its visitors in the forms of flight and firing simulators, a “battle dress uniform” corner where visitors can try on military attire, and helicopters, tanks and other vehicles on which visitors selected by lotteries are invited to ride. .[2] These museums are comparable to such institutions as “the world’s largest and oldest military aviation museum,” the United States Air Force Museum at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base in Ohio, the 1991 California State Military Museum in Sacramento, and the National Museum of the Pacific War in Fredericksburg Texas, established by the Admiral Nimitz Foundation. Founded by military units or veterans’ groups, these museums emphasize military strategy, the heroism of the nation’s commanders and soldiers, and the ingenuity and sheer force of its military technology.

Display at the Japan Army Self Defense Force, Asaka PR Center

“Battle Dress Uniform” corner Asaka

Other museums reject the legitimacy of war altogether and condemn World War II in particular. The oldest and best-attended of these, the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, established in 1955 by Hiroshima City, spreads anti-nuclear messages internationally. The organizers of that museum were motivated by a desire to commemorate the victims of the atomic bomb, provide evidence of their suffering, and work towards the abolition of nuclear weapons. Impelled by the knowledge that the generations who experienced the war will soon be gone, a number of so-called “peace museums” opened in Japanese cities in the 1990s to record and preserve the experiences of local fire-bombing victims and to pass on the message that war is a disastrous way to solve disputes. These include the private Oka Masaharu Memorial Nagasaki Museum (Oka Masaharu Kinen Nagasaki Heiwa Shiryokan), notable for focusing primarily on Japan’s war crimes in Korea and China and the travails of forced laborers from those areas. While there is nothing dedicated to the cause of peace on the scale of the Hiroshima Museum in the United States, smaller institutions such as the Peace Museum in Chicago proclaim a similar message. This kind of museum has endured the most controversy in Japan.

The Hiroshima Bridge that was the target of Enola Gay, August 8, 1945

The Atomic Dome in the Hiroshima Peace Park

Peace Osaka

The publicly funded Japanese municipal museum with perhaps the most profoundly self-critical analysis of the Asia-Pacific War is the Osaka International Peace Center, or Peace Osaka, which opened in a corner of the Osaka Castle Park in September 1991. The museum evolved out of long-term efforts by local citizens’ groups and news media to remember the impact of the war on Osaka, efforts that included collecting, recording and exhibiting the air-raid experiences of local residents. [3]

Peace Osaka Exterior

The main objective of Peace Osaka was to educate contemporary local residents about the approximately fifty American air-raid attacks that the city suffered during the last years of the war. In order to explain why the city was attacked so many times, the planners agreed on an exhibit that portrayed Japan as not only the victim but also the aggressor: it showed that while the air-raids and the atomic bombs caused tremendous suffering, the war was the result of Japan’s assaults in Asia. The exhibit also explained that Osaka Castle Park, in the heart of the city, was used as a munitions factory during the war. While this information was absolutely accurate, mention of it acknowledged that Osaka had been a military as well as a civilian target, potentially justifying the American bombardment. In other words, the museum was established by local residents, many of whom had contributed to smaller exhibits since the 1970s, in order to institutionalize “collective remembrance,” built around testimony of local suffering due to the policies of both the U.S. and Japanese governments. These Osaka residents also wanted to incorporate remembrance of Asian suffering inflicted by the wartime Japanese into the museum’s narrative. The fundamental message was that war should always be avoided.

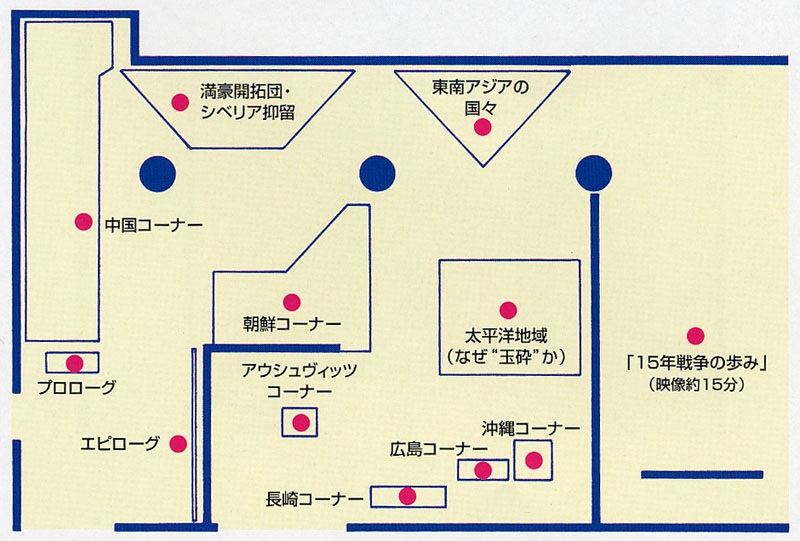

Osaka Castle Park Map

When the museum opened, the same message was reflected in curatorial decisions. The first wall panel sets the tone with its assertion that “Japanese people (nihon no kokumin) caused great hardship to Asian and Pacific people. Japanese also suffered….We must work for global peace.” The first of three sections, Exhibit Room A, shows the Osaka air raids and how they affected people’s daily lives through artifacts, replicas (including life-sized models of 1-ton bombs and incendiary bombs, which are the first objects to greet the visitor entering the room), film footage, photographs, and artwork. Exhibit Room B examines the fifteen year war as experienced by Japanese civilians and Asians who lived in the colonies and occupied territories. The exhibit discusses such Japanese actions as the bombing of Chongqing and the Nanjing Massacre, for which Japanese commanders were later convicted of war crimes at the Tokyo Tribunal, and also other atrocities for which they were not prosecuted, such as the activities of the biowarfare Unit 731. The final exhibit expands the message that peace everywhere is the paramount goal by addressing contemporary conflicts throughout the world, the ongoing danger of nuclear weapons, and environmental degradation. Business Manager Otsuki Kazuko explained that curators believed that no visitor could attain full understanding of the Osaka war experience without viewing both Exhibit Rooms A and B, emphasizing the extent to which Osaka was economically, politically, and socially part of the Japanese Empire during the war years. [4]

Floor Plan, Room B, Peace Osaka

Exhibit Room B, Peace Osaka

There was no outspoken opposition to this portrayal of the war until 1996, when conservative groups, after their success in Nagasaki, turned their attention to Peace Osaka. Just as with the Nagasaki case, conservative media outlets including the Sankei newspaper and journals Shokun and Shukan shincho published numerous articles penned by members of right-leaning groups with such innocuous names as the Japan Policy Institute (Nihon seisaku kenkyu sentaa) and the Japan Conference (Nippon kaigi), as well as by members of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), which had dominated postwar politics since its creation in 1955 but had recently been forced to accept a coalition government. On October 18, the LDP caucus of the Upper House published a “Research report on Japanese war museums (Zenkoku no senso hakubutsukan ni kansuru chosa hokokusho),” in which they criticized Peace Osaka as a “center for propaganda activities based on a politically biased ideology Stepping up the campaign, in March 1997, Osaka-based members of several of these neonationalist groups formed the Group to Correct the Biased Exhibits of War-Related Material (Senso shiryo no henko tenji o tadasu kai or Tadasu kai for short), whose exclusive focus seems to be attacking Peace Osaka. [5]

Although the planners of Peace Osaka had done an excellent job of addressing difficult issues honestly, involving knowledgeable experts in creating the exhibits, and mobilizing public opinion when creating the museum, for reasons explained below, the staff later failed to draw on any of these resources in response to the attacks. Their other major mistakes have been to avoid direct discussion of the issues at the heart of the conflict and to try to avoid controversies—particularly criticism from the right—at any cost. For example, unlike other peace museums where volunteers discuss the exhibits with visitors, Peace Osaka has prohibited their own oral history narrators from talking about subjects other than their personal experiences. It has also withdrawn educational worksheets that it had created for school children after receiving criticism that they were “too biased.” The museum staff, buffeted between competing views has adopted a defensive posture to maintain the status quo as their main strategy for brokering among them.

Strategies for Managing Controversy

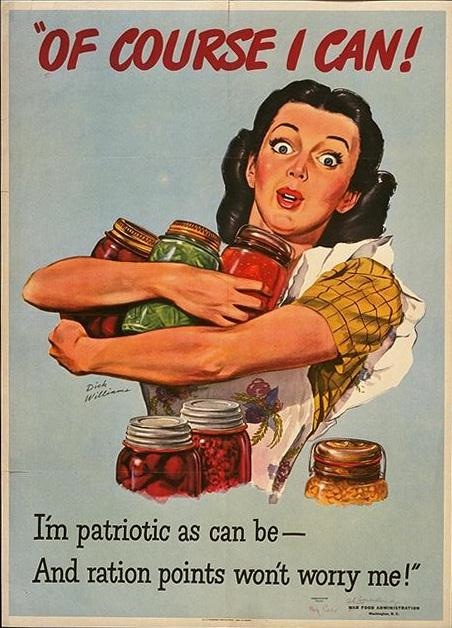

Other museums have handled competing pressures in different ways. One common, albeit unsatisfying, strategy is to limit war-related exhibits to uncontroversial aspects of any given subject, with only tiny hints of larger interpretive contexts and minimal reference to hot-button issues. This often means focusing on the experience of civilians and emphasizing daily life on the home front or front lines rather than battle strategy. One American example is the 1995 exhibit at the National Museum of American history on “World War II: Sharing Memories” which opened immediately after the Enola Gay fracas. Much of that exhibit focused on the home front, particularly the contributions women made to the war by planting vegetable gardens, buying government bonds, and working at jobs previously held by men.

WWII U.S. Government poster: winning the war on the home front

Even the sections on the military focused on foot-soldiers rather than generals and made the point that soldiers’ chief concerns were often unconnected to national policy. The section on “The Things They Carried” showed the contents of individual soldiers’ pockets.[6] In another example of minimal analysis on a controversial topic, the National D-Day Museum, which opened in 2000 in New Orleans, limited its discussion of the use of the atomic bomb to a photo of the mushroom cloud and the bland observation that its use “changed the world forever[7]

In Japan, everyone can agree that life was very difficult for both civilians and soldiers during the war. There is far less agreement on four related issues, however. First, some Japanese wish to blame wartime suffering on the policies of the government, which started a bloody war it could not win with little concern for the well-being of its own national subjects, while others focus only on the enemy airplanes, warships, and guns that were the direct cause of most Japanese casualties. Secondly, Japanese differ on how to think about the responsibilities of ordinary citizens for the war. Third, some Japanese have long argued that all Japanese should recognize the suffering they caused others as well as themselves, while others find that topic inappropriate for history education directed at school children, because it interferes with the task of cultivating “a healthy nationalism.” Finally, some Japanese believe that postwar peace and prosperity was only possible because the wartime leadership was defeated and discredited, while others argue for a more positive legacy from the war years. The solution to bridging these differences is often an exhibit focused only on daily life of ordinary citizens with little reference to these difficult issues.

Women getting rations in wartime Japan

Two museums in Tokyo, both funded by the state for the consolation of groups that were adversely affected by the war, employ this tight focus: the Showakan in Kudanshita and the Peace Memorial Prayer and Exhibit Hall (Heiwa Kinen Tenji Shiryokan), located on the 31st floor of the Sumitomo Building in Shinjuku, Tokyo. The mandate to “console” survivors has sharply limited the scope of both museums. Initially named “Memorial Hall for the Children of the War Dead” (Senbotsusha Iji Kinenkan), and later “Peace Prayer Hall in Commemoration of the War Dead” (Senbotsusha Tsuito Heiwa Kinenkan), the Showakan was intended as a memorial to comfort senso iji, or children who lost their fathers during the war. The project was initiated in 1979 as the state’s indirect response to requests for monetary reparations from the then-grown children whose fathers had died as soldiers. These “war orphans” who pushed for reparations are members of the politically powerful Japan Association of Bereaved Families (Nihon Izokukai), which propagates a very positive view of the war. Former Prime Minister Hashimoto Ryutaro, who also served as president of the Japan Association of Bereaved Families, fought for this project out of his belief that “the current prosperity of Japan was built upon the pain and suffering of its people during and immediately after the war,” endorsing the view that the war was beneficial and justified the willing and valued sacrifice of its soldiers. Yet the Showakan concentrates entirely on civilians.

Showakan exhibit: Family prepares for air raid

This is because one of the museum’s initial regulations had stipulated that the exhibits show as little war as possible – a decision reached by the planning committee after contemplating the request by the Association of Bereaved Families that the exhibit avoid giving the slightest impression that the fathers of the senso iji had died unnecessary deaths or behaved less than honorably.[8]

The Shinjuku museum is based on a clashing premise: that war is never worth the suffering. Ironically, however, it sends the same message as does the Showakan because both institutions were designed to console survivors by publicizing the story of their suffering. The Shinjuku Peace Hall was established in 2000 to “console three groups of people by educating the general public about the difficulties they faced”: soldiers who are not eligible for pensions since they did not fulfill their service requirements (mostly because they were drafted near the end of the war); Japanese detained in Siberia after the war; and civilian repatriates from Manchuria and other parts of East Asia. The Exhibit Hall is meant to teach visitors about the hardships these groups experienced through its display of artifacts and visual aids. While the Fund was established in response to complaints by the three groups, each of whom felt they were not receiving the reparations they deserved, it is oriented more toward publicity than monetary reparation. The exhibit has a rather peculiar format, of three sections, each with precisely the same layout, organization, and numbers of items displayed; a result of the effort the organizers took to be absolutely fair.

Diorama of repatriates in Shinjuku Peace Memorial Prayer and Exhibit Hall

Curator Furudate Yutaka has defined the most important goal of the Exhibit Hall as pleasing all visitors, by which he means all Japanese visitors. [9] He believes that the displays must not have a narrative or present a particular viewpoint that might offend anyone. His strategy is to drastically limit contextual explanations of the chosen topics—including such questions as why so many Japanese civilians were living in Manchuria in 1945. Furudate believes that if he strips away all interpretive framing of the exhibit, which is likely to provoke controversy, and reduces it to only the materials directly relating to the daily lives of foot-soldiers, Siberian prisoners, and civilians trapped in China, the enormity of their suffering will convey the anti-war message he hopes to send. While some context is provided in the brief timeline presented at the entrance of the hall, the exhibits themselves focus on artifacts and personal narratives in order to convey the typical experience of each group. The one strong perspective that does emerge—precisely because it is not controversial–is that war causes great suffering. The result is that his museum in many ways closely resembles the Showakan exhibit, even though the Exhibit Hall’s planners and core constituencies are far less vocally supportive of the war than is the Association of Bereaved Families. Neither museum feels politically free to state its philosophical position boldly, and both concentrate on the same limited subjects, hoping that the public will draw likeminded conclusions or at least will refrain from attacking the museum staff down the road.

A second common strategy for avoiding controversy in both countries has been to present a pastiche of individual experiences rather than one overarching narrative. Many curators of history exhibits now evoke a variety of personal memories and images among museum goers without trying to integrate them completely—collecting memories rather than collectivizing them. This approach, which tries to extend the range of individual perspectives as much as possible without losing a sense of the representativeness of each interviewee, was pioneered in literary form for World War II by Studs Terkel in The “Good War”, and his vision is now reproduced in many other artistic forms, museum exhibits among them. Such a collection of individually distinct memories is often a conscious political act that asserts the humanity and individuality of people who were persecuted as an undifferentiated group, as with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum’s videotapes of the recollections of survivors.

This strategy has been particularly useful for acknowledging the sensitive history of race relations in the United States. Even curators who fervently wish to avoid any controversy can no longer choose one white soldier to stand in for everyone; the simple act of organizing an exhibit as a collection of varied stories immediately highlights the specific experiences of non-whites. Yet often exhibits go farther because many curators, like many other Americans, now see the struggle for racial equality as central to the American story. American museum exhibits on World War II now routinely discuss what the D-Day Museum calls the “lamentable American irony of World War II,” that the armed forces were racially segregated throughout the war. This is a huge development fueled by African-American insistence that their struggle for equal treatment not be forgotten. Similarly, new attitudes about race made possible long-term exhibits such as “A More Perfect Union” at the National Museum of American History which opened in 1987 and treated wartime internment of Japanese Americans as a violation of civil rights that diminished constitutional protections for all Americans, not just for those of Japanese descent.[10]

The Army censored this photo because it showed African American Soldiers on burial detail,

as usual, and the Army was sensitive to criticism that this assignment was race-based.

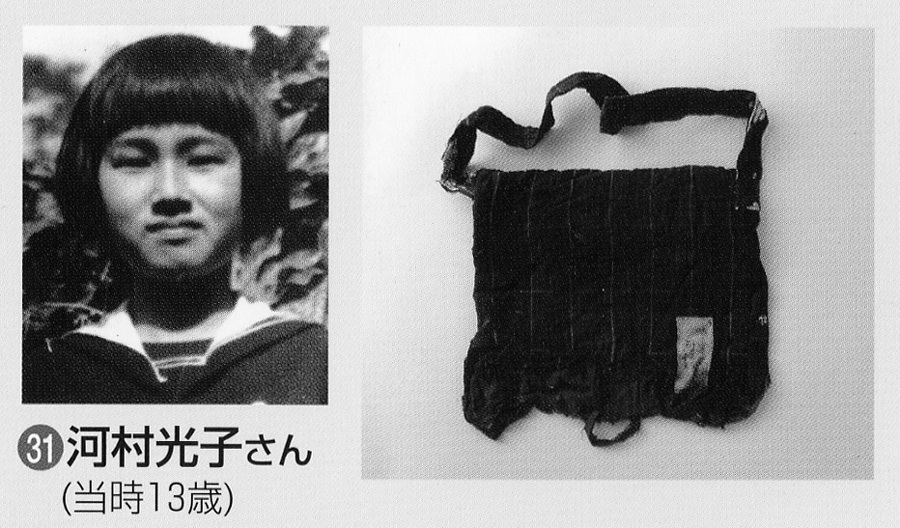

Like their American counterparts, many Japanese museums, including the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, Peace Osaka, the Okinawa Prefectural Museum, and the two Tokyo museums, provide written or videotaped personal testimony for visitors’ perusal. Some of these museums, including Peace Osaka and Showakan, also encourage elderly volunteers to talk to visitors about their experiences within the walls of the museums. The Hiroshima Museum has space for temporary exhibits, which typically focus on individual life stories and testimony, including a 2004 show about school children mobilized for war work. Yet these museums generally present personal narratives as illustrations of a typical experience rather than using them to sketch out the full range of individual experiences. The Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum is a significant exception, in that it has incorporated into its video collection the oral narratives of non-Japanese survivors, including forced laborers from Korea.

Curators and Their Audiences

In the United States, the controversy over the Enola Gay exhibit spurred museum professionals to intensify a process already underway: reexamining their practices in order to more effectively interact with the public they served. Museum professionals inside and outside the Smithsonian learned from the mistakes made at the Air and Space Museum. As one curator put it, “The Enola Gay controversy moved the Smithsonian from being a 19th century organization to a 20th century one. It became more professional and sophisticated about meeting public and scholarly expectations.” Another Smithsonian curator concurred, “In the post Enola Gay world of history museums, curators must think increasingly carefully about the tone of exhibitions. Once we did not much worry about what the public brought with them to exhibits, but that is not the case anymore. The public is demanding to be considered a partner in the creating of meaning. This is good, but the trick is how to share authority with your public while not simply abandoning the job of the curator and the historian.”[11] The essential point is that museum professionals rethought their relationship with their audiences as one in which curators and visitors collaborate in creating the narratives they use to understand the world around them.

Many of the most articulate and thoughtful museum professionals have concluded that if museums wish to continue be places where people can create meaning for themselves, curators must give up the idea that there is a single correct interpretation of an event as major and complex as World War II. They now believe that museum exhibits should be open-ended and also should reflect a multiplicity of views. As Lonnie Bunch, now Director of the National Museum of African American History and Culture, who has written extensively on strategies for handling political controversy over exhibits, explained, “Museums must not look to educate visitors to a singular point of view. Rather the goal is to create an informed public.” Leslie Bedford argues that “the public has the right to participate” and the “days of an authoritative curatorial voice are gone.” Museums, in this view, “are in the business of creating environments that facilitate the construction of appropriate meanings that engage people in the stuff of science, art, and history.”[12]

Another way to describe this approach is that curators, after recognizing that people have a right to challenge curators’ claims to determine how to interpret the past, have reconceived the exhibition as something that develops out of interaction with the audience. As Lisa Roberts argues, “Interpretation is in part an act of negotiation—between the values and knowledges upheld by museums and those that are brought in by visitors.” Conceptually, the goal is to “share the job of interpretation, of creating meaning, with our visitors” while at the same time, challenging them to think in fresh ways about their past. But most of all, as Leslie Bedford argues, it is “important to realize how profoundly people want to participate and leave their mark, and make sense of things in their own way.” Rather than giving up all control, sharing the job of interpretation with the public requires explaining far more explicitly than in the past how curators choose topics, themes, and objects for display.[12]

This attitude is less prevalent in Japan, in part because most peace museum staff members are not professional museologists, especially those at institutions that are funded and operated by cities and prefectures. Rather, most are career civil servants, who just happened to be appointed to the curatorial division of a peace museum as part of their regular rotation through local government. These people, whose other appointments typically include such jobs as issuing vehicle licenses and managing national health insurance, usually have little prior knowledge of operating a museum or curating exhibits, let alone professional post-graduate training. Civil servants’ appointments typically last three to five years, after which they move to completely different positions. Moreover, these local officials lack expertise in the history of the war, making it difficult for them to articulate an effective defense of their institutions.

One way that new attitudes about the relationship between museums and their audiences has changed exhibit practice in the United States is that American museums now typically provide materials for visitors to both add their own comments and read those of earlier visitors. This has worked well in exhibits related to WWII. Indeed, this was the most popular aspect of World War II: Sharing Memories. Space for public debate was also a major feature of a 2004 on-line exhibit at the Exploratorium in San Francisco, based on Yamahata Yosuke’s photographs of Nagasaki taken just after the atomic bombing there.

While Japanese museums also typically give visitors opportunities to provide feedback, usually in the form of questionnaires and/or notebooks located at the end of exhibits, most museums do little with the accumulated information. Nor do visitors have the opportunity to read the comments by other visitors. In the case of Peace Osaka, the staff is reluctant to incorporate comments for fear of generating controversy requiring changing the exhibits, and currently use the questionnaire sheets only to catch simple mistakes, such as incorrect dates, names, or English translations.

Hiroshima, by contrast, uses feedback from visitors to create a controlled dialog among curators. The museum staff gathers questionnaire sheets, notebooks, and exit interviews of visitors to the museum, and circulates the collected information internally. Employees also shadow selected visitors to understand their movement patterns and conversations as they go through the museum. Their findings are then used to modify the exhibits. These are standard methodologies used by museums all around the world and it is not surprising that Hiroshima, one of the few museums to have professionally trained staff, has most fully adopted them.[12]

Confronting Irreconcilable Differences

Yet, while essential, reshaping the museum-audience relationship into a more collaborative endeavor between museums and the public will never be enough because there is no undifferentiated “public” in either America or Japan The challenge is not just to articulate multiple viewpoints or extend the right to participate in exhibit-making. The more difficult and important task is developing strategies by which curators can negotiate between irreconcilable groups within the public–something that many museum professionals have yet to fully acknowledge. Moreover, whenever one group demands sole control over interpretation, it is impossible to satisfy everyone. If, as increasing numbers of museum professionals believe, the entire public has a right to participate in ascribing meaning, groups demanding monopoly control cannot be accommodated without invalidating the entire project. This is a dilemma difficult to resolve.

More precisely, in both nations, the ugliest fights have occurred when the audience in question was young people. Rather than allowing them to reach their own conclusions about the war, both American critics of the Enola Gay exhibit and Japanese ones of Peace Osaka demanded sole interpretive authority in order to shape the attitudes of young people about the war. American veterans who opposed the original Enola Gay exhibit were so insistent because they feared that introducing questions about the moral or strategic value of using the atomic bombs and even simply recognizing Japanese suffering would lead younger American viewers to think of the Allies and Axis as morally equivalent combatants. The central issue was whether displaying civilians in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in a sympathetic manner—people who indisputably had been harmed by American state action—was dangerous for American children. Tom Crouch recalls that one of the key moments in the negotiation process with the American Legion occurred over precisely this point. A Vietnam-era vet told Crouch that he had given the first script of the exhibit to his 13-year-old daughter to read and she had been horrified by American use of the bomb on civilians. The veteran then told Crouch “I can’t let you mount an exhibit that does that.” [13] This individual, like his allies, feared what young people would do with information that he has had for decades, showing the vastness of the gulf they imagine exists between the generations.

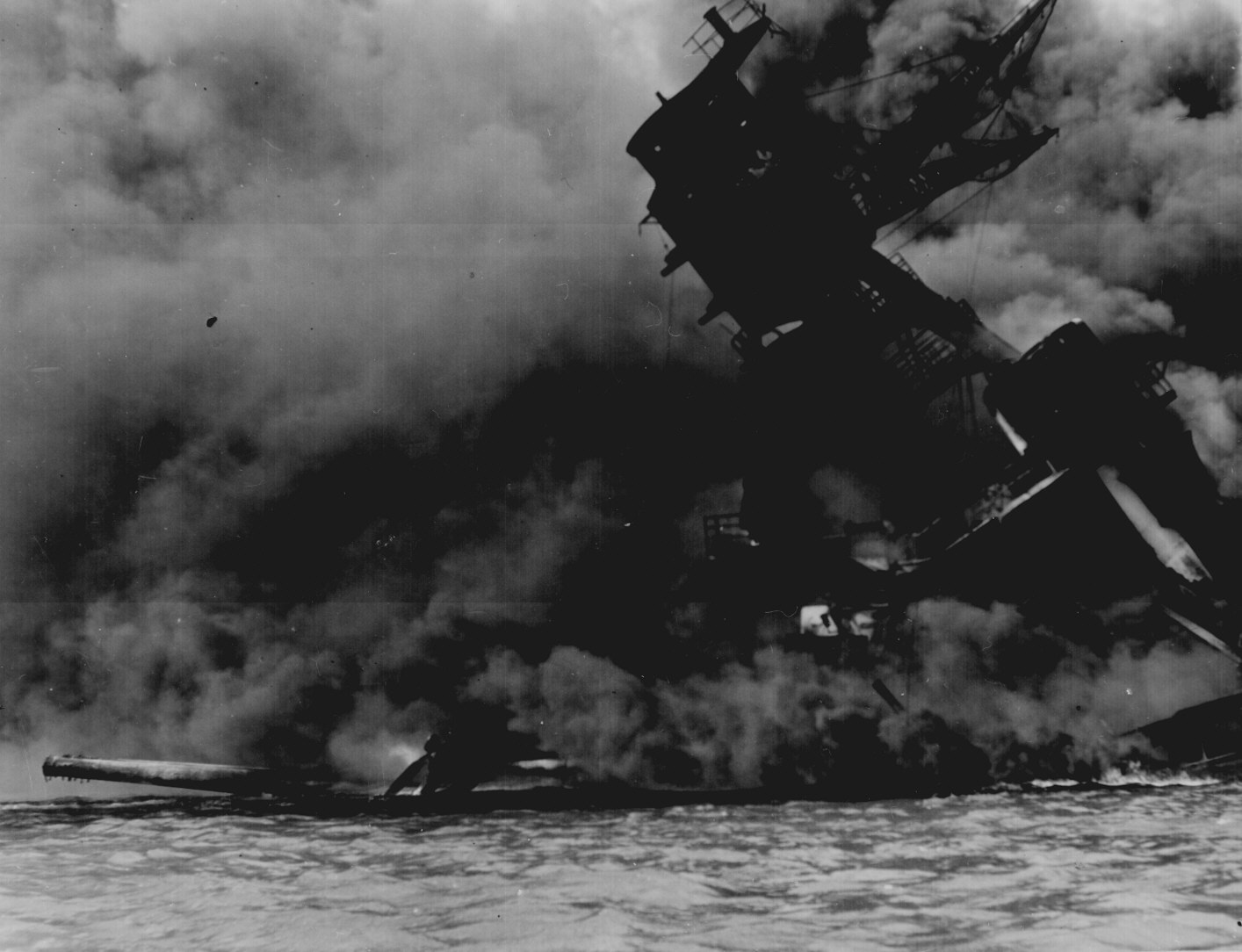

In Japan, too, most controversies about war memory focus on shaping the attitudes of young people, as evidenced by the perennially thorny issue of textbook representations of the war. Initially World War II museums were peripheral to this issue because so many of them were originally conceived of as a religious memorial to the dead and/or a service to survivors. Indeed, many of the war-related museums in Japan combine the function of a religious or secular memorial (or both—the line is usually blurred) with the educational mission of a museum. This combination is not unknown in the United States, where prominent examples include the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum and the USS Arizona Memorial at Pearl Harbor, but is more common in Japan.

Japan’s oldest war museum, the Yushukan Museum, is the most famous of these memorials and the most fully situated within Shinto ritual. This museum is annexed to Yasukuni Shrine, the controversial “war shrine” that memorializes all Japanese who died in uniform since the Meiji Restoration, including war criminals from the Asia-Pacific War. Those war criminals, convicted at the Tokyo Trials, were belatedly enshrined in 1978, in an earlier postwar attempt to control the museum’s representation of the war. Like many other Shinto shrines, the museum exhibits the belongings of the people memorialized there as a religious practice.[14]

Yushukan Atrium exhibits a Zero Fighter

Yet many of the state-sponsored and private peace museums also have an ambiguous memorial function, signified by the term “kinenkan” or “prayer hall” in their names. As indicated in their founding statements, these museums originated out of a project to “memorialize and honor (irei kensho)” the deceased. Peace Osaka, for example, is a “site to memorialize the war victims of Osaka The museum fulfills that memorial function in part by collecting the names of all the local war dead in order to set their souls at rest, like the explicitly religious Yasukuni shrine. The Okinawa Prefectural Peace Memorial Museum similarly states that one of its goals is to “mourn for those who perished during the war,” while the Himeyuri Peace Memorial Museum was built because the survivors of the Himeyuri corps (female students mobilized as nurses during the Battle of Okinawa) believe that working toward peace is the best way to console the souls of their colleagues who lost their lives in 1945. This responsibility to the souls of the dead intensifies the problem created by defeat and helps explain why many museum officials and visitors feel uneasy about exploring the proposition that the dead gave–or were forced to give–their lives for a useless cause. The Okinawa Peace Museum addressed this issue in a unique and politically powerful way: by naming everyone who died in the Battle of Okinawa, regardless of nationality, and so separating the issue of commemorating the dead from nationalist celebration.

Filipino Boy, Juan Castillo, wounded by Japanese bayonet

Interestingly, both the 1995 exhibit World War II: Sharing Memories, and the Showakan were originally designed primarily for the sake of elderly visitors who remembered the war. “The Things they Carried” section of “Sharing Memories,” in particular, was designed to encourage older American visitors to reflect on their own lives by presenting collages that conveyed individual differences within a common experience. The curators hoped that the objects themselves would lead veterans to recall their own lucky talismans and wartime gear. Similarly, the Showakan’s Curatorial Division manager, Watanabe Kazuhiko, explains that the initial objective of the hall was not peace education, but a display of everyday artifacts from the war and occupation years, in order to provide a “therapeutic effect” for the now-mature senso iji visitors by reminding them of benign aspects of their past. Most people agreed that older people already understand the context of the artifacts and assumed that they had the right to draw their own conclusions about the exhibit, a generosity not extended to young people.

Yet, as it turns out, an increasingly large share of Japanese history museum-goers are kids on school trips. For example, 65 percent of Peace Osaka’s visitors are elementary and junior high school children on field trips. Echoing the anxieties of their American counterparts, Japanese critics of peace museums fear young Japanese will accept what they think of as a “Tokyo Trials view of history,” one that indicted Japan’s war without recognizing either Japan’s legitimate complaints in the 1930s or acknowledging the fact that the United States, Britain, Germany, indeed most major combatants, engaged in such behavior as aerial bombardment of civilians, although only Japan and Germany were prosecuted for it after the war. They worry that young Japanese will believe that Japan still carries a moral taint, and that this belief will keep them from asserting Japan’s global interests in the future.

These exhibit designers are searching for a single unified narrative of the war that will convey to children an unambiguous message: that the war was a disaster for all involved, in the case of Peace Osaka, and that Japanese fought for a noble cause, in the cases of the Showakan and Yushukan. At the Air and Space Museum, the victorious critics forced the curators to acquiesce to the message that the use of the atomic bombs in 1945 was both righteous and necessary. In each example, the sharpest conflicts occurred when one group (sometimes inside the museum, sometimes outside) insisted that teaching patriotism required refusing to engage criticisms of one’s own government. In this view, the state has the right—sometimes framed as the obligation– to present its own actions in the best possible light to its own younger citizens. Frequently this means withholding information that has been common knowledge for decades. More fundamentally, in both nations these celebrants of state power deprive young people of the opportunity to engage exhibits through their own ethical and historical questions, leaving them ill-equipped to face a complex and morally ambiguous world.

Museum exhibits on World War II have another largely neglected audience—international visitors. Even though most debate assumes the primary audience is domestic, many museum visitors come from overseas, particularly in major tourist locations such as Honolulu and Hiroshima. Moreover, cities such as Washington and Osaka have substantial populations of permanent residents who hold foreign passports. Neither American nor Japanese museums have fully grappled with this fact, although Japanese museums try harder to accommodate foreign visitors than do American ones. In general, Japanese must accommodate international opinion on the topic of World War II far more than do Americans, reflecting greater American power in the world. This imbalance, of course, is one important source of rightwing Japanese anxiety about the attitudes of their younger compatriots.

One way museums accommodate foreigners is bilingual or multilingual signage and recorded material. Both the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and the Yushukan have translated all their captions into English, and visitors can listen to the survivor testimony on computer monitors in the Hiroshima museum in five languages. Other museums, such as Peace Osaka and the Okinawa Peace Museum have translated key sections of their exhibits into English. The Okinawan museum also posts a smaller portion of their exhibit in Korean and Chinese.

The Hiroshima Museum demonstrates its concern for international visitors in other ways. For example, it offers no opinion on whether the United States committed a war crime by using the atomic bombs on civilians. The museum’s silence is almost certainly out of sensitivity to American attitudes, because there is no controversy among Japanese on this point. In contrast to the United States, few Japanese today view the use of the atomic bomb as an ambiguous moral issue. The near-universal opinion there is that the attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki were clearly war crimes under the definitions incorporated into law and applied retroactively in the postwar Nuremberg and Tokyo War Crimes Trials.

By contrast, American exhibits on World War II have not expanded their focus to encompass foreigners in the same way that they have included the perspectives of American women, African Americans, and Japanese Americans. Nor is it likely they could do so without sparking criticism, since this sharp distinction between citizens and foreigners is obvious in many other aspects of contemporary American life, including American history textbooks and American responses to the 9/11 terrorist attacks

The Enola Gay exhibit controversy suggests that Americans are not yet willing to take Japanese opinions into consideration when designing exhibits about the war despite widespread American demands that Japanese modify their war memories. Although many Americans think the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum should include information about the attack on Pearl Harbor to help explain why the atomic bombs were used almost four years later, they see no need for the Arizona Memorial in Pearl Harbor to include mention of the later devastation at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Yet, according to Yujin Yaguchi, many Japanese visitors would like just that, not to diminish the losses in Hawai’i, but “to complete their sense of the narrative framework of the war.” They do not visit Pearl Harbor out of nationalist pride. Rather, to them, the key message is that war is a tragedy for everyone, and recognition that neither side emerged unscathed best conveys that message[15]

Pearl Harbor: USS Arizona after Japanese attack on December 7, 1941

Yet the well-established trends in museum practice described above can become equally powerful tools for expanding American imaginations beyond their compatriots. First, the focus on individual experience is easily extendable to include foreigners. In fact, the simple act of shifting one’s imaginative focus to individuals rather than nation-sized protagonists makes the nationality of those individuals seem far less important then their participation in common humanity. John Hersey pioneered this mental shift in his account of six individuals in his 1946 book, Hiroshima, which has had an enormous impact on American readers ever since. In a similar spirit, the National D-Day Museum in New Orleans, while unabashedly nationalist, collects reminiscences of the war from all participants—including Japanese, Filipino, and Chinese– not just Americans.

Hiroshima Memorial Museum exhibit on students working in central

Hiroshima on August 8th, focusing on them as individuals

Moreover, recognition of the humanity of Japanese-Americans automatically calls attention to Japanese nationals, since immigrants were barred from becoming U.S. citizens because they were not white. Most of them retained Japanese citizenship not because of loyalty to Japan but because of racist discrimination. Moreover, some American citizens of Japanese descent were trapped in Japan during the war, many of them in Hiroshima. They were treated as enemies by both the American and Japanese governments. These issues all are reflected in the permanent exhibit and collection of personal memories of the war at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles.

White Man’s Neighborhood: in the aftermath of Pearl Harbor

And, if racism is a problem when it occurs at home then surely it is a problem internationally. Building on the pioneering work of John W. Dower in War Without Mercy, many Americans now recognize that racism was a significant factor in both American and Japanese conduct during the war. The National D-Day Museum devotes a section of its permanent exhibit to “racial stereotyping, demonization, and warfare in the Pacific Theater of World War II,” acknowledging that racism played a large role in intensifying the violence on both sides of that conflict.

Cartoon by David Low on display at the National D-Day Museum

Further, simply documenting the troubling history of global genocide, war crimes, state terrorism, and systematic cruelty itself encourages comparative thinking, particularly about instruments of mass death such as the atomic bombs. The process of defining and explaining subjects necessarily involves abstraction and therefore a template for comparison. If bombing civilians at Guernica or Shanghai was wrong, how exactly were Nagasaki and Hiroshima different? One may conclude that they were, but simply going through the mental exercise establishes criteria for comparison and judgment. Evidence that many Americans have already taken such an imaginative journey for various aspects of state terrorism or war crimes is visible in debates such as over whether genocide is taking place in the Darfur region of the Sudan, including a discussion of “genocide emergency Darfur” on the U.S. Holocaust Museum’s website, or over the propriety of reparations to African Americans for slavery. The concept of “holocaust” has been borrowed to describe actions as diverse as the Nanjing Massacre of Chinese by Japanese soldiers in 1937, the AIDS crisis among gay men in the 1980s, and legal abortion in the United States since 1973, spurring much debate over principles of comparison. The International Coalition of Historic Site Museums of Conscience, a “world-wide network of organizations and individuals dedicated to teaching and learning how historic sites and museums can inspire social consciousness and action,” explicitly presents the subjects of children as victims of war, state terrorism, human trafficking and slavery, and racism, among others, as equivalent across national boundaries. This website links thirteen museums, including the Terezin Memorial in the Czech Republic, the Gulag Museum at Perm-6 in Russia, the District Six Museum in South Africa, the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, and the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site in Atlanta. While each of these museums focuses on a specific history of persecution, by linking them as equivalent “sites of conscience,” the international coalition effectively uses the global technology of the world wide web to pose the question of comparability of experience across national borders.[16]

Finally, to return to the history of American use of the atomic bomb on Japanese civilians in 1945, many Americans have never been comfortable with the official A-bomb narrative because it never fit well within the story of a nation that fights only for the right reasons when it must—or within a framework of proportionate retribution. Indeed, people come to look at the Enola Gay airplane at the National Air and Space Museum because they already see it as a complex symbol of many things. Robert R. Archibald, a former curator at the museum who spent several hours eavesdropping on visitors at the eviscerated 1995 exhibit, reports that an American woman struck up a conversation with a Japanese tourist, asking her, “How does it make you feel when you look at this?” Soon a dozen people had joined them. As Archibald explains, “The ensuing discussion was precisely the one that politicians and representatives of veterans’ organizations worked so furiously to prevent. There was no demeaning of the sacrifices made by veterans nor was there any question of their jubilation at the war’s end. Yet standing there in the shadows of the Enola Gay, there was profound acknowledgment that this airplane had ushered in the atomic age and the threat of unparalleled destruction.”[17]

Precisely because the Enola Gay never has been a simple symbol of the end of the war, it never can become only that. If, as museum professionals now emphasize, visitors brings their own meaning to exhibits, display of the Enola Gay will forever provide an invitation to debate the moral and strategic legitimacy of the use of the bomb in August 1945 even though the exhibit itself attempts to assert only one point of view. As museum professionals now understand, precisely because those concerns are invoked but not addressed by the presenters of the airplane, visitors will feel their absence and raise them over and over again.

Notes

[1] Asahi News Oct. 25, 1993 and January 3, 1996. Kamata Sadao “Nagasaki genbaku shiryokan no kagai tenji mondai, Kikan senso sekinin kenkyu 14 (Winter 1996), 22-31.

[2] Boei hakusho 12 nendo-ban, shiryo-hen: jieitai no koho shisetsu nado . Accessed May 27, 2005. Harada Keiichi, “Senso to heiwa no shiryo ni tsuite: Jieitai gokoku jinja no shiryokan tanbo-ki,” Kikan senso sekinin 14 (Winter 1996):15-21.

[3] The Asahi newspaper started an annual exhibition in August 1975, as did the Yomiuri newspaper. In 1977, groups such as “The Group to Record War Experiences (Senso taiken o kiroku suru kai),” the Osaka branch of the “Japan China Friendship Association (Nitchu uko kyokai),” and the “Osaka History Educators’ Association (Osaka Rekishi Kyoikusha Kyogikai),” collaborated to mount the exhibition series “War and ourselves (Watashitachi to senso).”

[4] Otsuki Kazuko interview with Akiko Takenaka, February 3, 2005, Osaka.

[5] Koyama Hitoshi, “Peace Osaka mondai: saikin no keika ni tsuite,” Hisutoria 159 (April 1998), 133-136. Also Senso shiryo no kenko tenji ‘tadasu kai’ Osaka de Kessei, Sankei March 2, 1997l.

[6] Steven Lubar “Exhibiting Memories,” in Exhibiting Dilemmas: Issues of Representation at the Smithsonian, Amy Henderson and Adrienne L. Kaeppler eds., (Washington, 1997), 15-27.

[7] See website of the National D-Day Museum in New Orleans. Accessed June 22, 2004.

[8] Tanaka Nobumasa, Senso no kioku” sono inpei no kozo: Kokuritsu senso memoriaru o toshite (Tokyo, 1997), 21-22. Ogawa Naotaro, “Showakan to sono shuhen,” Rekishi chiri kyoiku 597 (Aug. 1999), 98-102. For a brief account in English, see Ellen Hammond, “Commemoration Controversies: The War, the Peace, and Democracy in Japan,” in Laura Hein and Mark Selden eds., Living with the Bomb, M.E. Sharpe, 1997, 100-121. For Showakan, Watanabe Kazuhiro interview with Akiko Takenaka, Tokyo, Jan. 26, 2005.

[9] Furudate Yutaka interview with Akiko Takenaka, Tokyo, January 30, 2005.

[10] Accessed June 3, 2005. This exhibit is now only on line.

[11] Quotes from Lonnie Bunch interview with Laura Hein, May 28, 2004 and Steven Lubar “Exhibiting Memories,” p. 24.

[12] Quotes from Lonnie Bunch, “Fighting the Good Fight,” Museum News, 21 (March-April 1995), 32-35, 58-62 and Leslie Bedford, Director, Leadership in Museum Education Program, Banks Street College of Education, interview with Laura Hein, May 21, 2004.

[13] Tom Crouch, interview with Laura Hein, June 29, 2004.

[14] John Breen, Yasukuni Shrine: Ritual and Memory, Japan Focus, June 3, 2005.

[15] Japanese Visitor Experiences at the Arizona Memorial,” Yujin Yaguchi, in Laura Hein and Daizaburo Yui, Crossed Memories: Perspectives on 9/11 and American Power, Center for Pacific and American Studies, The University of Tokyo, 2003, pp. 138-151.

[16] Available here.

[17] Robert Archibald, “Epilogue to ‘The Last Act,’” Museum News November-December 1996, pp. 22-23, 56-57, quote p. 57

This essay is an abridged version of “Exhibiting World War II in Japan and the United States since 1995” , Pacific Historical Review, 76.1 (February 2007): 61-94 . Copyright © 2007 by the Pacific Coast Branch, American Historical Association. Reprinted by permission of The University of California Press, Journals and Digital Publishing. Posted at Japan Focus on July 20, 2007.

Laura Hein is a professor of Japanese history at Northwestern University and a Japan Focus coordinator. The Japanese translation of Reasonable Men, Powerful Words: Political Culture and Expertise in 20th Century Japan is being brought out by Iwanami Press in July 2007 as Riso aru hitobito to chikara aru kotoba—Ouchi Hyoe guruupu to kodo.

Akiko Takenaka teaches architectural history and theory in the Department of the History of Art at the University of Michigan. She is the author of “Architecture for Mass-Mobilization: The Chureito Memorial Construction Movement, 1939-1945,” in Alan Tansman ed., The Culture of Japanese Fascism (Duke University Press, forthcoming). She is currently working on a book manuscript on the history and politics of Yasukuni Shrine (tentatively titled Yasukuni: Nationalism, Violence, Memory).