Kimie HARA

The post-war Asia-Pacific witnessed many conflicts involving major regional players. These include the divided Korean Peninsula, the Cross-Taiwan Strait problem, and the sovereignty disputes over the Southern Kuriles/“Northern Territories”, and the Tokdo/Takeshima, Diaoyu/Senkaku, and Spratly/Nansha islands. These and others, such as the ongoing Okinawa problem, emblematic of the large US military presence in the region, and the US-imposed outcomes in Micronesia, all share an important common foundation in the post-war disposition of Japan, notably the 1951 San Francisco Peace Treaty. Prepared and signed by multiple countries under US initiative, this treaty largely framed the post-war political and security order in the region, and with its associated security arrangements, laid the foundation for the regional Cold War structure, namely the “San Francisco System”.

My recent book, Cold War Frontiers in the Asia-Pacific, from which the present article draws, examines the history and contemporary implications of the “San Francisco System” with particular attention to frontier and unresolved territorial problems that are among its important legacies. Drawing on extensive archival research as well as contemporary documentary analysis, it uncovers key links between regional problems in the Asia-Pacific and their underlying association with Japan, and explores clues for their resolution within the multilateral context in which they originated. The work’s contents illustrate its range and scope.

Introduction: Rethinking the “Cold War” in the Asia-Pacific. (1) Korea: The Divided Peninsula and the Tokdo/Takeshima Dispute. (2) Formosa: The Cross-Taiwan Strait Problem. (3) The Kurile Islands: The “Northern Territories” Dispute. (4) Micronesia: “An American Lake”. (5) Antarctica. (6) The Spratlys and the Paracels: The South China Sea Dispute. (7) The Ryukyus: Okinawa and the Senkaku/Diaoyu Dispute. Conclusion

Cold War Frontiers in the Asia-Pacific: Divided Territories in the San Francisco System

Micronesia: “An American Lake”

(d) Japan renounces all right, title and claim in connection with the League of Nations Mandate System, and accepts the action of the United Nations Security Council of April 2, 1947, extending the trusteeship system to the Pacific Islands formerly under mandate to Japan.[1]

The territories disposed in Article 2 (d) of the San Francisco Peace Treaty were the Pacific Islands formerly under League of Nations mandate to Japan, commonly known as Micronesia. On April 12, 1947, the United Nations Security Council decided to create the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI) by placing them under its strategic trust, with the USA as the administrative authority. The TTPI was one of eleven trusteeships established by the UN after the Second World War, but the only one designated a “strategic area”. Japan, not a member of the UN at that time, accepted the decision in the Treaty.

Trusteeship is a transitional arrangement preceding self-government, not a final disposition of territorial sovereignty. In this sense, the Peace Treaty left an “unsolved problem” with Micronesia, as with the other territories disposed of in it. However, the “problem” of sovereignty was settled in the 1990s. In 1994, with the independence of Palau the last, all UN trust territories disappeared from the globe. These islands are currently three sovereign states — the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), the Republic of Marshall Islands (RMI) and Republic of Palau (ROP) — and a US territory, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands (CNMI).

However, some problems remain over the status of these islands. The FSM, RMI and ROP joined the UN, thus becoming members of the international community. However, they are also in a status of “Free Association” with the USA, their former administrative authority. Under Free Association they are deemed sovereign, but the USA is granted particular powers in defense and security in return for economic assistance. Thus, according to Gary Smith, “while ‘sovereign’, they are less than independent.”[2] In addition, the CNMI, a US territory, has neither control over its 200 nautical-mile Exclusive Economic Zone, nor representation in Congress.

Micronesia encompasses over 2,000 islands, fewer than 100 of which are inhabited, spread across an ocean area from 1º to 20º N. latitude and from 130º to 170º E. longitude covering some 3,000,000 sq. miles (7.7 million sq.km)., larger than the US mainland. The land area, however, totals only 687 square miles (1760 sq. km), less than half the area of Rhode Island, the smallest state in the USA.[3] Since the Spanish proclaimed sovereignty over the Marianas in 1564, they have known four foreign rulers, Spain, Germany, Japan and the USA, the last two under the general supervision of the League of Nations and United Nations respectively.

Treatment of Micronesia in the Peace Treaty is based on “the action of the United Nations Security Council of April 2, 1947”. Therefore, this article focuses on the events leading up to the 1947 UN action. [Unless specified, e.g., as “Federated States of Micronesia (FSM)”, the terms “Micronesia”, “Japanese Mandated Islands” and “Trust Territories of the Pacific Islands (TPPI)” here indicate the same geographical area.]

FROM YALTA BLUEPRINT TO SAN FRANCISCO SYSTEM: THE COLD WAR AND MICRONESIA

Micronesia in the Yalta Blueprint – UN Trusteeship

Micronesia’s sovereignty did not belong to Japan, which received a League of Nations mandate over these former German possessions under the 1919 Treaty of Versailles. The December 1943 Cairo Declaration implicitly referred to Micronesia in stipulating that “Japan shall be stripped of all the islands in the Pacific which she has seized or occupied since the beginning of the First World War in 1914.”

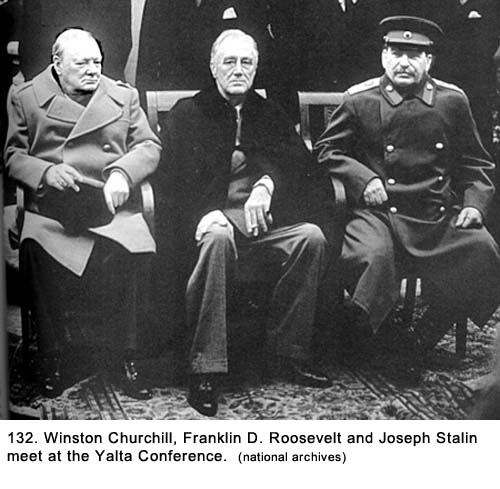

American occupation of the islands was complete before the Yalta Conference of February 1945. Beginning with invasion of the Marshalls, it was completed by a sweep through the northern Marianas by mid-1944.[4] Among agreements made at Yalta, relevant to the post-war disposition of these islands, were those on the UN and post-war trusteeship.

The UN was established in 1945 as successor to the League of Nations, with the objective of restoring international order after the Second World War. The name “United Nations” was coined by President Roosevelt in 1941 to describe the countries fighting against the Axis, and was first used officially in January 1942, when 26 states joined in a Declaration, pledging to continue their joint war effort, and not make peace separately. The need for an international organization to replace the League of Nations was first stated officially by the USA, UK, USSR, and China in their Moscow Declaration of October 1943. At the Dumbarton Oaks Conference of August-October 1944, those four drafted proposals for a charter for the new organization, and at the Yalta Conference in February 1945, substantial agreements were made to establish international trusteeship under the UN.

At Yalta, the three leaders agreed on a draft UN Charter, which included the basic provisions of the trusteeship system.[5] They agreed that territorial trusteeship would apply only to: (1) existing League of Nations mandates, (2) territory to be detached from the enemy as a result of war, (3) any other territory that might voluntarily be placed under trusteeship.[6] They also agreed that unlike the mandate system, all trust territories would have a clearly recognized right to eventual self-determination, but that in some cases the administering authority would have the right to fortify its territory, a power denied under the League, for international peace and security.[7]

It should be noted that the UN is the organization created by the Allied Powers in their post-war planning. It was the “United Nations” of the victorious Allies, and its mechanism was tinged in various ways with a strong power principle. For example, the original membership was limited to the Allied countries, five of them were given veto power in the Security Council, and former enemies, members of the Axis powers, received discriminatory status. The trusteeship system was created in this context.[8] Various wartime principles were unconditionally applied to the enemies, but applied very flexibly, or not at all, to the Allied Powers. For example the principle of self-determination of peoples, enthusiastically promoted by the USA, was not applied to all colonies. Category (3), as mentioned above, implicitly acknowledged the European allies’ interests, i.e., their colonialisms’ continuation.

Micronesia in the San Francisco System: Strategic Trust

In August 1945, nuclear weapons ended the war with Japan unexpectedly early, and their development dramatically changed the nature of post-war international relations, i.e., they became a major factor defining the Cold War. On August 17,1945, by General Order No. 1, the Japanese-Mandated islands along with Bonin and other Pacific Islands were placed under the Commander-in-Chief, US Pacific Fleet. In 1946 the USA began to use Bikini and Eniwetok atolls in the Marshall Islands for nuclear tests.[9]

Prior to the Japanese surrender, the UN founding conference was held in San Francisco in April 1945. As agreed at Yalta, all the states that had adhered to the 1942 declaration and had declared war on Germany or Japan by March 1, 1945, were invited to the conference, which was co-hosted by the US, UK, Russia and China.[10] The USA submitted a draft of the trusteeship system in the UN Charter that included a definition of “strategic trust”.[11] The Charter was signed on June 26, and came into effect on October 24.

On February 26, 1947, the USA submitted to the UN Security Council a trusteeship proposal, which designated the Japanese Mandated Islands an area of strategic trust, with the USA as administering authority. On April 2, the Security Council unanimously adopted the proposal, with a few modifications.[12] Japan, not then a UN member, renounced its right to these islands and accepted the trusteeship agreement in the Peace Treaty in 1951.

“Strategic trust” differed from other trusteeships, in that it allowed the administering authority to fortify and close any parts of the strategic area for “security reasons.” The trusteeship agreement could not be altered or terminated without the administering authority’s consent. Furthermore, the strategic area was the responsibility of the Security Council, where the USA had the power of veto.[13] The USA therefore gained exclusive control of these islands for as long as it wanted. Together with its bases in Okinawa, also placed under US control in the 1951 Peace Treaty, the USA obtained formal acquiescence to its control over the Pacific north of the Equator from Hawaii to Asia. In other words, the Peace Treaty laid the foundation for designating the North Pacific “an American Lake”.

When and how did the idea of strategic trust come about? Why was only the TTPI designated a strategic area? Why was only the disposition of Micronesia decided without waiting for the Japanese Peace Treaty? Why did the other powers, especially the USSR, accede to the arrangement? This examines the post-war disposition of Micronesia with the territorial arrangements of the San Francisco Peace Treaty at the center of analysis.

THE “UNRESOLVED PROBLEM”: DISPOSITION OF MICRONESIA IN THE PEACE TREATY

Early US Studies– behind the Yalta Blueprint

In the series of US studies on the post-war Japanese territorial dispositions dating from 1942, all State Department Far East specialists were guided by the Atlantic Charter principle of “no territorial aggrandizement” – territories should not be acquired by force, and those so acquired should be taken away. While the islands of Micronesia were under Japanese administration, they were not under Japanese sovereignty, and unlike the far-flung empire spanning East and Southeast Asia, they were not directly acquired by Japanese force of arms.

T-Documents:

Among the wartime State Department studies was a series of T-documents on the post-war disposition of Micronesia, prepared by the Division of Special Research and discussed in the Territorial Subcommittee in 1943. They are T-328 “Japan’s Mandated Islands: Description and History” dated May 27,[14] T-345 “Japan’s Mandated Islands: Legal Problems” dated July 8,[15] T-365 “Japan’s Mandated Islands: The Mandate Under Japanese Administration” dated August 9,[16] T-367 “Japan’s Mandated Islands: Has Japan Violated Mandated Charter and the Convention of 1922?”[17], and T-370 “Japan’s Mandated Islands: The Maintenance and Use of Commercial Aircraft” both dated September 1.[18]

As the numbers and titles of these records suggest, Japanese administration of Micronesia was examined in detail from various angles in State Department. It was considered appropriate to deprive Japan of control of its mandated islands after the war. As the title of T-367 suggests, it was strongly based on the point “Has Japan Violated Mandated Charter and the Convention of 1922?”[19] The report concluded:

In summary, Japan violated the Mandate Charter and the United States Convention of 1922 by erecting fortifications and building naval bases on the islands; the United States Convention, by infringing the rights of the American missionaries, and by refusing to permit certain American citizens to visit the islands and United States naval vessels to enter the open ports of the mandate; and apparently the Mandate Charter by failure to meet its obligations to the natives.[20]

For the disposition of these islands, T-345 suggested:

For every reason, practical, ethical and possibly even legal, it may seem advisable to the United States and others of the United Nations to deal with Japan’s mandated islands by means of a new multilateral treaty or treaties, which while respecting the principle of trusteeship embodied in the Treaty of Versailles would dispose of these islands in accordance with their own best judgment. These treaties may create a new system of trusteeship for various dependent areas including these islands. Such treaties will doubtless be signed at least by the principal United Nations and possibly at the demand of the victorious powers by the defeated states as well. The coming post-war settlement in short may be regarded, ethically and possibly legally, as superseding the settlement of 1919.[21]

These documents suggest that by the time of the Cairo Declaration there was already a blueprint for placing Micronesia under international trusteeship. While State Department envisaged trusteeship, there was, however, no consensus in the US Government as a whole regarding these islands’ precise post-war political status.

The US Military and Micronesia: JCS 183 Series

Unlike State Department, the military advocated US acquisition of Micronesia. Although the USA had become a strong advocate of such principles as “no territorial aggrandizement” or “self-determination of peoples” during the Second World War, it, too, was an imperial power that had expanded its territories to and in the Pacific in the late 19th century.[22] The main reason for the military’s claim to Micronesia was defense from Japan. Historically, the US military had seen Japan as a threat since the late 19th century, and its fears intensified especially after Japan gained control of Micronesia and fortified it. During the Second World War, US forces suffered severe losses from Japan’s effective use of these islands as strategic bases. The USA recognized Micronesia’s strategic value once again from the experience of this war. [23]

At the end of 1942, in response to a request by President Roosevelt, the newly created Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) undertook studies on the future position of post-war bases in the Pacific, the JCS183 series “Air Routes Across the Pacific and Air Facilities for International Police Force”.[24] As the title indicates, Roosevelt envisaged the bases as part of a US contribution to an “International Police Force”. While an international organization was hoped for, and the US, UK, Russia and China were expected to assume world-wide responsibilities for security, the military did not have confidence in future international cooperation. The study warned that if “a workable international organization cannot be established or …such an organization, once established …break(s) down again due to subsequent divergence of national policies,” then, “Consideration of our own national defense and the security of the Western Hemisphere and of our position in the Far East must, therefore, dominate our military policy during and after the war. Adequate bases, owned or controlled by the United States, are essential to properly implement this policy and their acquisition and development must be considered as among our primary war aims.”[25] The study argued that bases should be maintained in the area between Hawaii and the Philippines, including Japanese-Mandated Islands and Bonin as “essential to our national defense or for the protection of US interest.”[26]

Just as Japan saw Micronesia as one of the most important regions for its national defense, the US military in the course of the Pacific War came to regard it as a strategically focal area. After capturing Micronesia’s main islands, the USA dispatched B-29s from Tinian to attack Japanese positions one after another. Filling the gaps between US territories across the Pacific, i.e., the US mainland – Hawaii – Wake – Guam, if under US control, these islands would provide ideal unsinkable US aircraft carriers in regard to Asia. However, if under enemy control, they would expose US Pacific territories to a significant threat.[27] As the cost in lives and money mounted in the course of the war, not only the military but also Congress and the public supported their acquisition. A Gallup poll in May 1944 showed that 69 percent of respondents supported some sort of permanent US control over the islands after their conquest, whereas only 17 cent opposed it.[28] Roosevelt nevertheless intended to discuss the subject of trusteeship at the Dumbarton Oaks Conference in September 1944. However, it did not do so, due to strong opposition by the Army and Navy.[29] The USA was moving quietly but definitively toward the formation of a global network of bases that would become pivotal to the hegemonic strategy of the postwar era.

CAC-Document:

Against this background, CAC-335 “Japan: United States: Disposition of the Mandated Islands”[30] was prepared in December 1944 – January 1945 in State Department. The document presented several possibilities for the post-war status of these islands, which in accordance with the Cairo Declaration were to be taken from Japan. It provided detailed analysis, centering around (1) international trusteeship with the USA as the administering authority, and (2) transfer to the USA in full sovereignty, and recommended the first.

CAC-335 stated:

– Such a course would be consistent with the theory of international organization supported by the United States, which calls for collective security “by their own [member’s] action”, and for national administration of non-self-governing territories placed under international trusteeship.

– As these islands are already an international trust, a change from a trust status would be harmful to the whole concept of trusteeship and international organization. The Mandated Islands clearly cannot be treated as conquered enemy territory nor the rights in them of the Principal Allied and Associated Powers and of the League of Nations disregarded.

– This solution is therefore the only one which will obtain in combination the two objectives which are essential in connection with the disposition of the islands: United States control of vital security bases and the recognition of international authority over the Mandated Islands.[31]

The following rationales were added.

– International authority over the islands will strengthen and add to the prestige of the projected international organization which the United States is seeking to establish.

– American public opinion, as judged by polls and surveys, strongly favors “permanent control” by the United States of the Japanese Mandated Islands and wishes the United States to “keep these islands after the war”: a majority apparently wish this control to be exercised under some form of international authority.[32]

However, it also recognized the negative aspects of this solution.

– This suggested arrangement is more complicated than unrestricted United States sovereignty and involves the possibility of jurisdictional friction with the international organization.

– There is some question whether the United States will be able to obtain complete control of the bases under this plan.[33]

As for US sovereignty, which the JCS preferred as important for US security, it mentioned arguments that

– they should be assigned to the United States without international supervision.

– United States sovereignty over these islands would not necessarily interfere with an international security system.[34]

However, various considerations were raised against this solution.

– Annexation would be widely regarded as inconsistent with the provision in the Atlantic Charter against “territorial aggrandizement” and of the provision in the Cairo Declaration against “territorial expansion”.

– Among peoples in the Far East annexation of islands in the south and west Pacific might create an apprehension that American policy is embarking on an imperialistic course toward the Far East, and consequently might weaken the traditional confidence of these peoples in the United States.

– Annexation might be widely regarded as inconsistent with the principle of trusteeship which the American Government may wish to advocate, and make it difficult for the United States to urge upon other states acceptance of international supervision over dependent areas in which they claim a special interest.

– It might force the United States to pay a substantial price for sovereignty: the necessity of acquiescing in objectionable demands of other states.[35]

Behind the Establishment of the UN Trusteeship System

The US military was not content with the trusteeship proposal, as it did not necessarily guarantee exclusive US control over Micronesia. In February 1945, at Yalta, the military again requested that discussion of trusteeship for Micronesia be avoided. Secretary of War Stimson asked that there be no open mention of the matter until “the necessity of … acquisition by the United States is established and recognized”. He argued

Acquisition of them by the United States does not represent an attempt at colonization or exploitation. Instead, it is merely the acquisition by the United States of the necessary bases for the defense of the Pacific for the future world. To serve such a purpose, they must belong to the United States with absolute power to rule and fortify them…[36]

Roosevelt nevertheless raised the subject at Yalta, but in general terms, without focusing attention on Micronesia.[37]

Strategic Trust:

Established at the end of 1944, the State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee (SWNCC) began fully to function as a central policy-making organization on Japanese issues at the beginning of 1945. In formulating policies on the Japanese Mandates, attention focused on means of altering the trusteeship provisions in the draft UN Charter to fit Micronesia’s peculiar qualities and to satisfy the US plan to build bases. In other words, it tried to pursue the policy of non-annexation insisted on by State Department, but at the same time to meet the military’s strategic objectives. What resulted was the concept of “strategic trust”, which had a number of distinguishing characteristics. First, it allowed the administering power to fortify the territory and close parts of it at will for security purposes. There had been no concept of designating strategic areas in the League of Nations’ mandate system, which prohibited military use. The conclusion of T-367 may be recalled. Thus, this innovation would enable the USA to do legally what Japan had done illegally. Second, the “states directly concerned” should have final authority to change the status of the strategic trust. Finally, unlike other trusteeships, affairs concerning a strategic trust would be dealt with in the Security Council, where the USA would have veto power.[38]

The draft of the trusteeship system submitted to the UN founding conference in April 1945 included description of strategic trust, but specified only the machinery and principles of trusteeship for inclusion in the UN Charter,[39] in conformity with a memorandum presented on April 18, 1945 by the Secretaries of State, War and Navy to Truman, who had just become President. It stated:

It is not proposed at San Francisco to determine the placing of any particular territory under a trusteeship system. All that will be dis¬cussed there will be the possible machinery of such a system.[40]

Truman approved this, and sent it to the US Delegation as a directive.[41] Adopted on April 26 and coming into effect on October 24 1945, the UN Charter provided in Chapter XI declarations regarding non-self-governing territories (Articles 73 and 74), in Chapter XII the international trusteeship system (Articles 75-85) and in Chapter XIII the trusteeship council (Articles 86-91). Pertinent extracts from articles bearing on the disposition of the Japanese Mandated Islands are:

(Article 77)

1. The trusteeship system shall apply only to such territories in the following categories as may be placed thereunder by means of trusteeship arrangements: (a) territories now held under mandate; (b) territories which may be detached from enemy states as a result of this war; and (c) territories voluntarily placed under the system by states responsible for their administration.

2. It would be a matter for subsequent agreement as to which territories would be brought under a trusteeship system and upon what terms.(Article 79)

The terms of trusteeship for each territory to be placed under the trusteeship system, including any alteration or amendment, shall be agreed upon by the states directly concerned, including the mandatory powers in the case of territories held under mandate by a Member of the United Nations, and shall be approved as provided for in Article 83 and 85.(Article 82)

There may be designated, in any trusteeship agreement, a strategic area or areas which may include part or all of the trust territory to which the agreement applies, without prejudice to any special agreement or agreements made under Article 43.[42](Article 83)

1. All functions of the United Nations relating to strategic areas, including the approval of the terms of the trusteeship agreements and of their alteration or amendment, shall be exercised by the Security Council. …(Article 84)

It shall be the duty of the administering authority to ensure that the trust territory shall play its part in the maintenance of international peace and security. To this end the administering authority may make use of volunteer forces, facilities, and assistance from the trust territory in carrying out the obligations towards the Security Council undertaken in this regard by the administering authority, as well as for local defense and the maintenance of law and order within the trust territory.(Article 85).

The functions of the United Nations with regard to trusteeship agreements for all areas not designated as strategic, including the approval of the terms of the trusteeship agreements and of their alteration or amendment, shall be exercised by the General Assembly…[43]

In a letter dated June 23, 1945 to the Secretary of State, the Secretaries of War and Navy stated that

The Joint Chiefs of Staff … are of the opinion that the military and strategic implications of this draft [United Nations] Charter as a whole are in accord with the military interests of the United States.[44]

It should be noted that there was as yet no governmental consensus on specific methods of trusteeship application, including area designation. As discussed in the next section, the military was then considering strategic trust not for Micronesia, but for different areas in the Pacific such as Okinawa and Iwo Jima. Therefore, under such circumstances, and also to provide room for interpretation, the provisions of the trusteeship system were confined to general references in the UN Charter.

Micronesia as a testing ground

During the first meeting of the UN General Assembly, held in London in January – February 1946, UK, Australia, Belgium and New Zealand announced their intention to put their mandated territories under trusteeship, and so did France shortly thereafter. The USSR initially opposed renewal of Italy’s mandate to administer Somaliland, but it was eventually approved. Only the USA and South Africa did not follow suit.[45] In fact Secretary of State Byrnes cabled Washington for permission to discuss the former Japanese mandates on this occasion. However, the military, specifically Navy Secretary Forrestal, persuaded Truman to refuse.[46]

One of the definite causes of US (in)action became clear in the same month. On January 24, 1946, half a year after the atomic bomb test in New Mexico, the USA announced that it was preparing to test atomic bombs at Bikini atoll in the Marshalls.[47] Two days before this announcement, the Joint Chiefs of Staff informed the Secretary of State that they considered it essential to US national defense that the USA have strategic control (1) of the Japanese mandated Islands, by assumption of full US sovereignty, and (2) of Nansei Shoto, Nanpo Shoto and Marcus Island, through trusteeship agreements designating those islands as strategic areas.[48]

On May 24, 1946, JCS presented study report JCS1619/1, which repeated the above views in respect of the Japanese Mandated Islands and the Nansei – Nanpo Shoto area,[49] but for Marcus Island proposed assumption of US sovereignty. The report stated that “security requirements of the (Nansei – Nanpo Shoto) area might be satisfied by establishment of trusteeship with the USA as administering authority, in which Okinawa and adjacent small islands and Iwo Jima are designated as a strategic area.”[50]

The JCS report further argued “Acquisition of full sovereignty by the United States would prevent possible efforts, during processing of trusteeship agreements through the United Nations, to weaken U.S. strategic control by dividing the area into more than one trusteeship or by preventing designation of the entire Japanese Mandated area as a strategic area.”[51] Expecting Soviet opposition, JCS was extremely skeptical about the prospects for obtaining exclusive US trusteeship over the Japanese Mandates. “Even though a strategic trusteeship over the entire area were guaranteed to the United States,” it argued “there is no certainty that the required exclusive U.S. control could not later be jeopardized through elimination of the veto power in the Security Council, followed by modification of the terms of trusteeship in a manner contrary to U.S. interests.”[52] Furthermore, it drew attention to “the possibility that, as a result of some crisis or impasse, the United States might be forced into a compromise, for reasons of expediency, which would nullify exclusive U.S. control of the area.”[53]

The report also attempted to justify US annexation of Micronesia by linking it to Soviet territorial gains in Europe and the cession of the Kuriles specified in the Yalta Agreement, made public early that year.[54] It stated:

It is believed that the USSR is the only power which might object, solely for ideological reasons, to the sovereignty over these mandates passing to the United States. Such Soviet position in this regard should be open to serious question, since the USSR has in fact assumed sovereignty over Latvia, Estonia, Lithuania, and Eastern Poland, although without US recognition, and apparently proposes to assume full sovereignty over the Kuriles.[55]

In addition,

Our interest in the Kuriles, in respect to trusteeships in the Pacific, is the implication of the precedent which would be set by the USSR in the assumption of full national sovereignty by any state over areas to be detached from the sovereignty of Japan.[56]

Linkage between Micronesia and the Kuriles was discussed also in the context of the trusteeship alternative.

In event the Kurile Islands are proposed for trusteeship, the USSR should be designated as sole administering authority in implementation of the Yalta Agreement. There are at present no indications that either Karafuto or Formosa will be offered for trusteeship.[57]

Truman’s statements of intent

Before the end of the war, Truman made several announcements that appear related to the future of these islands. These were released while the State Department and the military still held divergent views, and thus the expressions were unspecific. Nevertheless, he indicated that some arrangement would be made to secure US bases using trusteeship or some UN framework. For example, on August 6, 1945, after the atomic bomb was dropped in Hiroshima but before the USSR entered the war against Japan, he stated in a broadcast reporting on the Potsdam Conference:

…though the United States wants no territory or profit or selfish advantage out of this war, we are going to maintain the military bases necessary for the complete protection of our interests and of world peace. Bases which our military experts deem to be essential for our protection and which are not now in our possession, we will acquire. We will acquire them by arrangements consistent with the United Nations Charter.[58]

On January 15, 1946, in a press conference shortly after the opening of the General Assembly in London, Truman spoke about Micronesia.

The United States would insist that it be sole trustee of enemy Pacific Islands conquered by our forces and considered vital to this country’s security. Other former enemy islands now held by us but not considered vital to this country will be placed under United Nations Organization Trusteeship, to be ruled by a group of countries named by the United Nations Organization.[59]

Considering the USA’s historical involvement in establishing the UN, and the need to maintain consistency in US policy, outright annexation was impossible.

SWNCC 59 Series

From June through July 1946, in order to hammer out a unified US government policy, SWNCC59/1 “Policy concerning trusteeship and other methods of disposition of the Mandated and other outlying and minor islands formerly controlled by Japan” and its revised version, SWNCC59/2, were drafted and discussed. State Department prepared the basic drafts, in which US policy was formulated within the context of the UN Charter. The State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee informally approved SWNCC59/2 on July 15, 1946, and on the same day appointed an ad hoc committee with H. Borton as the steering member. From August through September, while the JCS retained the position that the USA should obtain sovereignty of Micronesia, the ad hoc Committee developed a draft trusteeship agreement.[60] Combining State Department’s draft of August 8 and JCS’ counter-draft of August 24, the SWNCC completed a draft trusteeship agreement text on September 19. It had the following distinguishing features.

(a) It designated the whole area as strategic;

(b) It specified that the goal should be self-government, not independence, thus announcing in advance that independence was not an objective;

(c) It provided, however, for full use of the Trusteeship Council on economic and social matters outside of any closed areas;

(d) It restricted any possible fiscal, administrative or customs union to a union “with other territories under United States jurisdiction” instead of with “adjacent” territories, as the original State draft; proposed; and

(e) It provided that the agreement could not be “terminated” without the consent of the United States.[61]

State Department persistently tried to formulate a trusteeship policy consistent with overall US policy. Yet it did not necessarily deny the future annexation of Micronesia on which the military insisted. After several months of indecision following the establishment of the UN, the US government moved to make known its intention to place these islands under trusteeship rather than annex them. If the trusteeship proposal was rejected, the USA would hold on to them as a de facto matter.[62] There was no need for haste to make the final decision on devolution. A memorandum requesting comments on this draft trusteeship proposal, sent from the SWNCC to the JCS, stated,

It is not intended that the submission by the State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee or consideration by the Joint Chiefs of Staff of this draft agreement shall prejudice the ultimate decision as to whether the strategic control desired by the United States over former Japanese-held islands is to be accomplished through sovereignty or through United Nations trusteeship.[63]

John Foster Dulles was then the US representative on the Fourth (Trusteeship) Committee in the UN General Assembly. In October, he urged the Government’s top decision-makers, including the President, “to make an authoritative and definite statement of US intention with regard to the Japanese Mandated Islands” at the next General Assembly meeting. He told Secretary Forrestal that “from an over-all standpoint the United States needed to demonstrate to the rest of the world its capacity to act decisively in relation to international affairs”. He explained that a number of countries doubted whether the USA had that capacity, and whether it was safe for them to associate themselves with the USA. The differences of opinion within the US Government over disposition of the Japanese Mandated Islands were already well known, and the indecision, if prolonged, could weaken the US position in the world. Thus, “while some decision was of first importance, irrespective of what the decision was”, he thought it important that the decision be for strategic trusteeship rather than annexation.[64] Dulles gave similar explanations to military leaders such as Admirals Nimitz and Sherman, while emphasizing that he thought it “entirely possible” and “proper to get” the military rights the Navy felt indispensable.[65]

On October 22, Truman brought the Secretaries of State, War and Navy together to discuss submission of the trusteeship agreement. He told them that the UN would first stipulate the form of a contract on trusteeships, and the USA would then offer the islands formerly under Japanese mandate for trusteeship under that form.[66] The military was apprehensive of this procedure. Navy Secretary Forrestal expressed the fear that “once negotiations were under way, subordinate officials of the State Department or some delegate to the United Nations might compromise and accept an arrangement that would jeopardize proper maintenance of the bases.”[67] In response, Byrnes assured him that only changes approved by the President or Secretary of State would be accepted.[68] On November 6, 1946, Truman announced that “The United States is prepared to place under trusteeship with itself as the administering authority, the Japanese mandated islands and any Japanese Islands for which it assumes responsibilities as a result of the Second World War”.[69]

Toward an American Lake: Reactions of Concerned States and US Reactions

From October to December 1946 the UN General Assembly was held in New York, and some of the pending trusteeship proposals were put up for approval, in the hope that the UN Trusteeship Council could be established.[70] On November 7 Dulles communicated to the Fourth (Trusteeship) Committee Truman’s statement of the previous day. Copies of the draft agreement were transmitted for information to the Security Council’s other members (Australia, Brazil, China, Egypt, France, Mexico, Netherlands, Poland, USSR and UK) and to New Zealand and the Philippines, and were later transmitted to the newly-elected Security Council members, Belgium, Colombia, and Syria.

Negotiations with the USSR

Soviet opposition was expected. Alger Hiss, Director of the Office of Special Political Affairs, recorded the anxieties Dulles expressed by telephone on the day before the US policy was officially announced.

He [Dulles] feels that the Russians are planning a campaign of obstruction to the proposed agreements. They have indicated they will emphasize the need for provisions looking toward early independence which would be unacceptable to the mandatory powers. If the Russians have a veto right they would then be able to prevent the establishment of the trusteeship system. Mr. Dulles said that he was inclined to feel that although the establishment of the trusteeship system is important, that establishment is really of less substantive importance than is the propaganda issue which the Russians are raising about what states are really the defenders of the dependent peoples. He said that once the trusteeship agreements were approved there will be relatively little of substance which the Trusteeship Council will itself accomplish and, as in the case of the mandate system, the administering powers will be responsible in fact for what goes on in their territories. … He indicated that he was anxious that we not get in a position of appearing to rush through the Assembly against Russian opposition agreements which are satisfactory to colonial powers. He said he thought the Russians would try to class us with the colonial powers.[71]

As expected, the Soviet media reported Truman’s policy announcement of November 6. On November 11 Pravda (Special Tass correspondent in New York Dispatch) wrote:

The unusually broad scope of the American plans likewise arouses surprise, as they include not only Pacific islands under Japanese mandate but also any other Japanese island US desires to possess. At same time various comments are aroused by USA’s attempt to make a considerable part of the Pacific Ocean with vast number of islands its strategic zone, which may be connected with plans for preparing a future war…[72]

Quoting the New York Herald Tribune of November 7, Pravda also wrote that the US proposal was intended to turn the Pacific Ocean into an “American lake” from San Francisco to the Philippines.[73] Red Fleet on November 19 carried an article “The USA and the Japanese mandated islands”, quoting a US military official, and criticizing the US plan as “US imperialist aspirations, and far from constituting interests of defense”.[74]

As stated earlier, the UN Charter requires each trusteeship agreement to be acceptable to the “states directly concerned” and for such agreements for strategic areas to be approved by the Security Council. How to handle these points was the critical key to approval of the US proposal. Dulles tactfully took the position that the definition of “states directly concerned” should not be determined until the Trusteeship Council was established.[75] As the country in possession of the islands, and to pursue its own strategic interests, the USA had to become the only state “directly concerned”. [76] However, it was better not to deal with this until the setting was ready and deals made.

The USSR was not necessarily against US trusteeship of Micronesia, but the terms of trusteeship had to be acceptable to it, and it did not favor the USA’s suggested procedure. During the General Assembly and Council of Foreign Ministers meetings in New York, behind-the-scenes negotiations were held, at which the USSR repeatedly tried to have the USA agree that the Security Council’s five permanent members be regarded as “states directly concerned” in all trusteeship agreements.

Dulles noted that in an unofficial meeting on November 28, Gromyko and Novikov

intimated that the Soviet Union was not particularly interested in being considered a “state directly concerned” so far as the African mandated territory was concerned, but that they stood absolutely on the proposition that they were a “state directly concerned” in so far as related to enemy territory, specifically the Italian colonies, any Japanese islands and the Japanese mandated islands. …It was their view that under the Charter there was no right to fortify for national purposes. … the only right was for international peace and security and that the only body which could administer international peace and security was the Security Council. … The concrete result of their theory was that the United States would not have the right to maintain bases in trusted Pacific Islands except as might be specifically authorized in each case by the Security Council, i.e., by Russia, and subject to its supervision and inspection.[77]

The US counter-argument was that

trusteeship would make it easier to move toward internationaliza¬tion of military establishments if and when the Security Council actually demonstrated that it could be relied upon to maintain the peace. However, that had not yet been demonstrated and until it was demonstrated we [USA] would want in the Pacific Islands the same rights that the Soviet Union would presumably exercise in such islands as the Kuriles Islands. We said that the Soviet Union had shown no disposition to accept for the Kuriles Islands the regime which it was seeking to impose on us as regards Pacific islands which might come under our administration.[78]

This was the argument linking Micronesia with the Kuriles discussed earlier (in the above JCS studies). The Soviet riposte was an effort to differentiate the cases.

They [USSR] said that this was different because it had been agreed between the United States and the Soviet Union that the latter could annex the Kuriles [sic] Islands.

The US side replied.

We [USA] said that that was an informal agreement which had not yet been ratified by peace treaty and that other nations than the United States were concerned in this matter, notably China.[79]

Needless to say, “China” here is the ROC. The record continues,

I [Dulles] said … that the United States would not agree to a double standard under which the Soviet Union did not subject to Security Council control areas in its possession which it deemed vital; whereas the United States, as to comparable areas in its possession, would be subject to control and inspection by the Soviet Union. Messrs. Gromyko and Novikov affirmed strongly that, if necessary, the Soviet would fight the issue through to the floor of the Assembly, and they expressed confidence that they could defeat approval of trusteeship agreements with provision for bases, etc.[84]

The USSR, however, then appeared to reconsider. A note of December 7 stated

The Soviet Government is prepared to take into account the interests of the United States of America in connection with this question, but at the same time it considers it necessary to express its view that the question of trusteeship over the islands formerly under Japanese mandate, as well as over any Japanese islands, must be considered by the Allied Powers in the peace settlement in regard to Japan …[81]

This appears to suggest that the USSR intended to make a deal over Micronesia and the Kuriles in the peace treaty settlement. On December 13, 1946 the General Assembly approved the first trusteeship agreements, for eight non-strategic former League of Nations mandates,[82] and on December 14 adopted a resolution on organization of the Trusteeship Council.[83]

In just over two months the Soviet position changed again. On February 20, 1947 Molotov informed Byrnes that the USSR intended to support the US proposal at the Security Council, without waiting for the Peace Treaty.

The Soviet Government has carefully considered your note of the 13th [12] of February of this year and has arrived at the conclusion that it is not worthwhile to postpone the question about the former mandated islands of Japan and that the decision of this question comes within the competency of the Security Council.

As regards the substance of the question, the Soviet Government deems that it would be entirely fair to transfer to the trusteeship of the United States the former mandated islands of Japan, and the Soviet Government takes into account, that the armed might of the USA played a decisive role in the matter of victory over Japan and that in the war with Japan the USA bore incomparably greater sacrifices than the other allied governments.[84]

The author could not obtain Byrnes’ “note of the 13th [12] of February replying to Molotov. However, available information appears to suggest three reasons for the Soviet change of attitude. (1) The USA limited the area of trusteeship application to Micronesia, (2) The Japanese Peace Treaty was expected to be concluded in the near future, and (3) A deal over the Kuriles.

For the area of trusteeship application, as seen in the next section, Byrnes sent a note to the British Ambassador on the same day as his note to Molotov (February 12). In it the USA justified its trusteeship proposal by differentiating Micronesia, a League of Nations mandate, from the other enemy territories. The revised US draft excluded the Nansei-Nanpo Shoto, such as Bonin, Okinawa and Iwo Jima, originally included in the trusteeship area (as denounced in the November 11 Pravda article). The USA stated that it was “proposing the agreement in full compliance with the trusteeship provisions of the Charter and was acting on the recommendation of the General Assembly of February 1946 which invited states administering former mandated territories to submit trusteeship proposals.”[85]

After the Paris Peace Conference of July – October 1946, peace treaties were signed with Italy, Hungary, Romania and Finland on February 10, 1947, i.e., ten days before this Soviet note. Thus, it was widely expected that a Japanese peace treaty would be next, and would feature at the Foreign Ministers’ Conference to be held in March-April in Moscow.[86]

Finally, the Soviet attitude was apparently largely based on a deal over the Kuriles. This was discussed not only among the two countries’ UN representatives (e.g., Dulles, Gromyko and Novikov etc.), but also at their Foreign Ministerial meetings. The record of the December 9 meeting shows that Byrnes repeatedly said he would communicate with “Mr. Dulles” before getting back to Molotov, who urged US acceptance of the Soviet position.[87]

Byrnes clearly indicated in his Memoirs that the Soviet change of attitude was because of linkage with the Kuriles.

Mr. Molotov asked me to agree that the five permanent members of the Security Council should be regarded as “states directly concerned” in all cases. … Such a definition of “states directly concerned,” I replied, was a matter of Charter interpretation within the United Nations itself, and should not be the subject of a bilateral arrangement between our two governments. I then added that I would bear his position in mind when considering the ultimate disposition of the Kurile Islands and the southern half of Sakhalin. This brought a very quick response. The Soviet Union, he said, did not contemplate a trusteeship arrangement for the Kuriles or Sakhalin; these matters had been settled at Yalta. I pointed out to him that Mr. Roosevelt had said repeatedly at Yalta that territory could be ceded only at the peace conference and he had agreed only to support the Soviet Union’s claim at the conference. While it could be assumed that we would stand by Mr. Roosevelt’s promise, I continued, we certainly would want to know, by the time of the peace conference, what the Soviet Union’s at¬titude would be toward our proposal for placing the Japanese-mandated islands under our trusteeship. Mr. Molotov quickly grasped the implication of this remark.[88]

The Security Council later voted on the US trusteeship agreement. The USSR did not use its veto, and the issue was resolved smoothly in accordance with US intentions. Byrnes also wrote,

I was delighted, but not surprised, to see that the Soviet representative voted in favor of our proposal.[89]

UK and Australia

The USSR was not the only country to display a negative attitude to the US trusteeship policy. Western Allies such as UK and Australia had no objection to US control of Micronesia itself, and had since wartime even favored US annexation of these islands.[90] However, they responded negatively to the US proposal, arguing, as did the USSR, that it was premature, and should wait for the Japanese peace treaty.

On January 21, 1947 British Ambassador Lord Inverchapel sent a memorandum to the Secretary of State. It stated that the British Government “regard the action of the United States Government as a declaration of intention which cannot take effect in advance of the Peace Treaty with Japan and consider that it would be premature at this stage to place proposals formally before the Security Council.”[91] In particular, from the British point of view such US action “would be open to the serious practical objection that it would confuse the issue about trusteeship for the former Italian Colonies.”[92]

On the same day (January 21), Australian Ambassador Makin also sent a memorandum to the Secretary of State. It stated,

In the view of the Australian Government, the ultimate solution of the ques¬tion of the Japanese mandated islands lies in their being controlled by the United States. At the same time the Australian Government does not regard this as an isolated question but as an integral part of a comprehensive settlement for the entire Pacific ocean area. To isolate the question of mandated islands from the settlement with Japan as a whole is, in the opinion of my Government, an approach almost untenable both politically and juridically.

With the fullest desire, therefore, to support the ultimate objective of the United States, the Australian Government regards both the timing and the procedure as erroneous, and believes that the course proposed by the United States will have the effect of adding to the difficulties of achieving their objective.[93] …..The United States Government recently undertook… to support the claim of Australia to be a principal party in the negotiation of the Japanese settlement. In view of this the Australian Government finds it difficult to understand the approach made by the United States Government on the question of the mandated islands, which appears to disregard Australia’s vital interest in the disposal of the territories concerned.[94]

In its reply of February 12 the USA defended its position.

The United States Government has no desire to contribute to any confusion of the issue about the Italian colonies. It does not see any obvious or direct connection between the two cate¬gories of territories in question. Although the territories in both categories are under military occupation, the status of the former Japanese Mandated Islands, having been for many years under an international mandate and never having been under the sovereignty of Japan, appears to be entirely different from that of the Italian colonies in these respects.[95]

After the United States’ formally submitted its draft trusteeship agreement to the Security Council on February 26, Australia proposed that the Security Council’s decision be finally confirmed at the Japanese peace conference, and that states not members of the Security Council that participated in that war should have an opportunity to discuss the terms of trusteeship.[96] Following this, New Zealand and India asked to be allowed to participate in discussion.[97] At last, after the discussions were broadened to include representatives of Canada, India, the Netherlands and the Philippines, Australia withdrew its objections.[98]

On April 2, 1947 the Security Council unanimously approved the US draft agreement with only a few minor amendments.[99] Eleven UN trust territories were then created, ten of them former League of Nations mandates. The only change in the administrative authority from the pre-Second World War period, was in former Japanese-mandated Micronesia.[100]

Micronesia in the Peace Treaty Drafting

In October 1946, when the General Assembly met in New York, the Peace Treaty Board, established in the Far Eastern Department of State Department, began post-war drafting of a peace treaty. Since the US decision to announce its trusteeship agreement plan had been taken around the same time, it appears that both the trusteeship agreement and the Japanese peace treaty were expected to be concluded in the near future. Soviet acceptance of the US trusteeship plan also apparently hinged on expectation of an imminent Japanese Peace Treaty, including a deal over the Kuriles. However, it took four years and five months from adoption of the trusteeship agreement (April 1947) to conclusion of the Japanese Peace Treaty (September 1951).

In the disposition of Micronesia, the various peace treaty drafts prepared in State Department from March 1947 focused mainly on Japanese renunciation. The dissolution of the League of Nations had not of itself terminated the Japanese administration, and it was therefore considered that the Peace Treaty must include Japan’s formal renunciation of her interest in, title to, or right to administer the islands. These drafts also attempted to extend the UN resolution formula to the other territories, i.e., Nansei – Nanpo Shoto such as Okinawa and Bonin Islands, and the British drafts prepared in 1951 also focused on Japanese renunciation of Micronesia. The US-UK joint draft prepared in May 1951 became the Peace Treaty text cited at the beginning of this Chapter.

AFTER SAN FRANCISCO: THE END OF TRUSTEESHIP

From signature of the trusteeship agreement until 1951, the islands of Micronesia were placed under civilian administration by the US Department of the Interior, except for most of the Marianas, which were soon returned to the Navy, and remained under Naval administration until 1961.[101] Some parts of the Marshalls also remained a closed area under Naval administration, and continued to be used for nuclear testing. The Northern Marianas, except Rota, were also closed, for use as a CIA training ground for guerillas to be landed in China.[102] However, in the whole Trust Territories of Pacific Islands (TTPI) consisting of more than 2000 islands, the number used for such military-related activities was very small, and there was no specific plan for using the others. For the USA, the greatest significance of the trusteeship was probably that it prevented enemies from using these islands’ strategic potential.[103] The general public, including Americans, were not allowed to visit the islands, and inhabitants’ travel overseas was also restricted.[104]

Yoshida Shigeru signs the San Francisco treaty as John Foster Dulles (left), Dean Acheson and Styles Bridges, the ranking minority member of the Senate Armed Forces Committee, look on

US policy toward the TTPI changed radically in the 1960s. The Kennedy administration introduced the Peace Corps, and extended many US federal programs, especially in health and education, to the TTPI. Planning for the territory’s future political status also began.[105] The major factor inducing this change in US policy was the independence movement of various UN trust territories that was developing then.[106] In 1965, the Congress of Micronesia was formed. Made up of representatives of the original six districts of TTPI (the Marshall Islands, Palau, Ponape, Truk, Yap, Saipan), it served for over a decade as the main agency of local self-government. In 1967 it established a Joint Committee on Future Political Status (JCFPS), which in 1969 issued a report recommending the TTPI’s future status be that of a sovereign state. Following this report, the USA entered into formal negotiations to end the trusteeship and determine the islands’ future political status. By 1975, with the independence of Papua New-Guinea, the other ten trusteeships created after the Second World War were all terminated. However, it took another fifteen years to terminate the TTPI.

Flag of the Trust Territories of the Pacific Islands

Flag of the Trust Territories of the Pacific Islands

As mentioned earlier, the goal of a trusteeship was self-government, not necessarily independence. The critical decision to move Micronesia “into a permanent relationship with the US within our [US] political framework” was approved by President Kennedy and adopted in his National Security Action Memorandum No. 145 of 18 April 1962.[107] He appointed a commission under Anthony Solomon to prepare a plan to promote Americanization.[108] A major goal of the Solomon Plan (1964) was “for a huge infusion of money and procedure to bind Micronesia to USA and, when that had been achieved, to offer a choice (through a plebiscite) of independence or permanent affiliation with USA, which the planners were confident would give USA permanent control of Micronesia as it wanted for US strategic reasons.”[109] The Solomon Plan was not formally adopted, but many of its proposals were implemented.

At the time when negotiations to terminate the TTPI began, the USA was facing a big turning point in its post-war world strategy involving a radical transformation in the Asia-Pacific regional international structure. In July 1969 US President Nixon announced the change in US Asian strategy that became known as the “Nixon doctrine”. The new US policies included withdrawal from Vietnam, reduction of US military bases in Asia, and increases in the self-defense effort of each country allied with the USA.[110] In addition, after return of the Bonin Islands to Japan in 1968, reversion of Okinawa was expected in the near future. There was no guarantee that the USA could freely continue to use its forward bases in Japan and the Philippines indefinitely. In addition, technological advances in weapons such as missiles could facilitate withdrawal of major forward defense lines as far back as Micronesia.[111] Thus the new US Asia policy increased Micronesia’s strategic importance.

During the early stages of the status negotiations, the US government intended to keep all six districts of the TTPI together as a single entity, as did the UN. But, the TTPI declined the offer of US territorial status. The USA then offered “commonwealth” status, similar to that of Puerto Rico. Under increasing pressure to release the TTPI, and also with the primary interest in it as a strategic fall-back area, US administrators, especially in the military, acted to bond the Northern Mariana Islands more closely to the USA by offering more jobs and money, higher pay, better schools with more qualified teachers, better hospitals, roads and other facilities. If the Marianas chose independence, they would lose these extra privileges.[112]

Thus the Marianas were encouraged to break away from the rest of Micronesia and join Guam as a US territory. As Crocombe wrote, “(a)lthough this was not US official policy – at least not acknowledged as such – it is what happened.”[113] In 1975, after a plebiscite, the Marianas separated from the other TTPI districts, to establish a Commonwealth of the Northern Marianas Islands (CNMI) in political union with the USA.[114] The US military’s goal of annexing Micronesia was finally realized in the CNMI, but by the inhabitants’ choice. As a result, the CNMI became the US forward base and defense line of the US territories in the Pacific.[115]

Negotiations with the remaining TTPI districts took almost a decade longer. In 1978 they voted on a Constitution. Yap, Turk, Ponape and the new Kosrae TTPI districts ratified a Constitution, forming the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM). The Marshall Islands and Palau ratified separate constitutions in 1979 and 1981 respectively, breaking away from the FSM, gaining self-government, and choosing free association with the USA for their future political status.

The Compact of Free Association defines the basic relationship between the USA and these associated states.[116] It recognizes an Associated State as sovereign, self-governing with the capacity to conduct foreign affairs consistent with the terms of the Compact. It sets the nature and amount of US economic assistance, and places full authority and responsibility for security and defense matters with the USA. Associated States are expected to refrain from actions that the US government sees as “incompatible with its authority and responsibility for security and defense”, and are therefore obliged to consult the US government in conducting their foreign affairs.[117] So if an Associated State engages in foreign policy moves viewed by the USA as “incompatible” with its defense responsibilities, it would be subject to potentially heavy economic penalties. These provisions are non-reciprocal; the Associated State has no say over US foreign or defense affairs.[118] In the words of Richard Herr, Free Association is the mechanism for “re-invention of the nineteenth-century concept of the ‘protected states’.”[119] The Micronesian states had to negotiate with the USA from a weak position, having grown heavily dependent on US assistance.

The governments of the FSM and the Republic of Marshall Islands (RMI) signed the Compact of Free Association in 1982, and it came into force in 1986. A major subsidiary agreement of the Compact with the Marshall Islands allows continued use for up to thirty years of the US Army missile test range at Kwajalein atoll. Although post-TTPI arrangements were made, the trusteeship was not terminated until 1990. By Article 83 of the UN Charter, the trusteeship status of a strategic area can be altered only by UN Security Council resolution. Denouncing the Free Association system as “new colonial rule”, not to mention the Commonwealth arrangement with the Marianas, the USSR regularly vetoed the trusteeship termination resolution.[120]

However, the dramatic changes in Soviet foreign policy in the late 1980s brought the end of trusteeship in Micronesia. On December 23, 1990, one year after the “end of the Cold War” declaration at the US-USSR Malta summit, the FSM, RMI and CNMI officially ended their trusteeship by Security Council resolution, and on 9 August 1991 the FSM and RMI joined the UN.[121]

Palau’s government signed the Compact of Free Association with the USA in 1986. However, Palau’s Constitution, which precluded nuclear activity, and US policy of neither confirming nor denying its use of nuclear-armed vessels, meant that it could not take effect until approved by the Palauan people in 1994. The USA wanted access for its military – nuclear or otherwise – but the Constitution mandated seventy-five percent voter approval to override the nuclear ban,[122] and seven plebiscites failed to make the change. In the meantime, the USA kept pressuring the Palauans to change their minds by various means, including withholding funds.[123] After the sixth plebiscite, the Constitution was amended, reducing the nuclear ban waiver requirement to a simple majority. On November 9, 1993, in the eighth plebiscite, sixty-eight percent of those voting approved the Compact.[124] On October 1, 1994, with Palau moving to Free Association with the USA, all UN trust territories disappeared.

The US “post-Cold War” security policy maintains strong focus on the Pacific region, and the Compact continues to provide a strategic insurance as well as valuable resources for it, particularly in the area of missile defense testing and development. Many economic provisions, including federal financial and program assistance, as well as the defense provisions, expired on the Compact’s fifteenth anniversary for the FSM and RMI (2001), but renegotiation resulted in new twenty-year agreements in 2003. For the ROP, US economic assistance expires in fifteen years (2009), and its defense responsibility in fifty years (2044). The Compact itself has no expiration date, thus Free Association continues, unless both parties agree to end it. The “American Lake” thus continues even after the end of trusteeship in Micronesia.

SUMMARY

US Government interest in the Pacific Islands has always been predominantly military and strategic. The idea of placing Micronesia under UN trusteeship with military bases existed in the Yalta blueprint. However, those bases were to be part of a US contribution to an “International Police Force” anticipating international cooperation, including with the USSR. For Micronesia, the foundation of the San Francisco System was laid in April 1947 by action of the UN Security Council, with Soviet consent. The concept of strategic trusteeship developed in embryonic form in the era of conventional warfare, but the atomic bomb, ironically first dispatched from Micronesia, introduced a new era.[125] To satisfy both strategic interests and diplomatic requirements, US policy on post-war Micronesia was formulated so as to alter the UN Charter’s trusteeship provisions. Negotiating astutely in the UN, the USA secured exclusive control of Micronesia. John Foster Dulles, who was involved in the key negotiations, later played the central role in drafting the Japanese Peace Treaty.

As mentioned earlier, trusteeship is a transitional arrangement, and not a final disposition of territorial sovereignty. No expiry date was specified for the TTPI, i.e., the USA gained indefinite control of the islands. The TTPI was an “unresolved problem” created by the Cold War. Following the end of the US-USSR Cold War, the TTPI came to an end in the early 1990s. As far as the Micronesian Islands are concerned, the “unresolved problem” of sovereignty was settled. Their continuing peculiar status, however, is a remnant of the Cold War, developed during the 1960s and 1970s, when the Asia-Pacific region was experiencing a structural transformation. The Micronesian economies remain heavily dependent on US funding today. In defense and security affairs, Micronesia is part of US territories. A contemporary implication of the San Francisco System is thus still observed in Micronesia’s status.

This article originated as chapter 4 of Cold War Frontiers in the Asia-Pacific: Divided Territories in the San Francisco System (Oxford and New York, Routledge, 2007), and is reproduced here by kind permission of the publisher. It appears here with a new introduction in a slightly edited form. Posted at Japan Focus on August 10, 2007.

See the related article by Kimie Hara, Cold War Frontiers in the Asia-Pacific: The Troubling Legacy of the San Francisco Treaty.

Notes

1. Conference for the Conclusion and Signature of the Treaty of Peace with Japan, San Francisco, California, September 4-8, 1951, Record of Proceedings, p.314.

2. Gary Smith, Micronesia; Decolonisation and US Military Interests in the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, Peace Research Centre, Research School of Pacific Studies, Australian National University, 1991, p.2.

3. Ibid.; Current Notes, No.23, 1952, p.40; Donald F. McHenry, Micronesia: Trust Betrayed, Altruism vs Self Interest in American Foreign Policy, New York and Washington: Carnegie Endowment For International Peace, 1975, p.6; Carl Heine, Micronesia at the Crossroads, A Reappraisal of the Micronesian Political Dilemma, Honolulu: An East-West Center Book, The University Press of Hawaii, 1974, p.3.

4. Ron Crocombe, The Pacific Islands and the USA, Rarotonga and Suva: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, and Honolulu: Pacific Islands Development Program, East-West Center, 1995, p.xxv; Harold F. Nufer, Micronesia under American Rule: An Evaluation of the Strategic Trusteeship (1947-77), Hicksville, New York: Exposition Press, 1978, p.26.

5. Roger W. Gale, The Americanization of Micronesia: A Study of the Consolidation of U.S. Rule in the Pacific, Washington DC: University Press of America, 1979, p.53.

6. FRUS: The Conferences at Malta and Yalta 1945, p.859. This later became Article 77 of the UN Charter adopted on October 24 that year. I

7. Gale, op.cit., p.53.

8. Ibid.

9. Between 1946 and 1958, at least sixty-six nuclear tests were conducted at Bikini and Eniwetok atolls. [Peter Hayes, Lyuba Zarsky and Walden Bello, American Lake, Nuclear Peril in the Pacific, Harmondsworth, England: Penguin, 1986, p. 72; Kobayashi Izumi, America gokuhi bunsho to shintaku tochi no shuen – soromon hokoku, mikuroneshia no dokuritsu (US Confidential paper and Termination of the U.N. Trusteeship – Solomon Report, Independence of Micronesia), Tokyo: Toshindo, 1994, p.13-4.]

10. US President F. D. Roosevelt, an earnest promoter of the UN, died before the conference, and was replaced by Truman.

11. Gale, op.cit., p.60.

12. FRUS 1947, Vol. I, pp.258-78; Nufer, op.cit., p28.

13. Stanley DeSmith, Microstates and Micronesia, New York: New York University Press, 1970, p.132; Gale, ibid., p.63.

14. RG59, Records of Harley A. Notter, 1939-45, Records of the Advisory Committee on Post-War Foreign Policy 1942-45, box 63, NA.

15. Ibid., box 64.

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.

18. Ibid.

19. On February 11,1922, Japan and USA signed a convention, by which Japan granted the USA and its nationals equality with Japan in cable rights, pledged that “no military or naval bases shall be established or fortifications erected in the territory” promised to send the USA a duplicate of its annual report to the Council of the League of Nations, etc. (T-328, pp.8-9, ibid.)

20. T-367, p.14, ibid.

21. T-345, ibid.

22. For example, in 1898, the US military took over Guam in the Spanish-American War, and annexed Hawaii. It also attempted to acquire other Spanish colonies in Micronesia, but was beaten to it by Germany. Wake Island was annexed as a US cable station. In 1899 the USA acquired Eastern Samoa (American Samoa).

23. Glen Alcalay, “Pacific Island Responses to U.S. and French Hegemony”, Arif Dirlik ed., What is in a Rim: Critical Perspectives on the Pacific Region Idea, 2nd Edition, Boulder, Colo.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 1998, p.310.

24. For a discussion of JCS 183, see Robert D. Eldridge, “Okinawa in U.S. Postwar Strategic Planning, 1942-46”, Kobe daigaku daigakuin hogaku kenkyu-kai, Rokkodai ronshu, hogaku seijigaku-hen, Vol. 45, No.3, March 1999a, pp. 64-71; Gabe Masaaki, “Bei togo sanbo honbu ni okeru okinawa hoyu no kento, kettei katei – 1943 nen kara 1946 nen –”, Keio gijuku daigaku hogakubunai hogaku kenkyu-kai, Hogaku kenkyu, Vol. 69, No.7, July 1996, pp. 84-87.

25. “JCS 183/6, Air Routes Across the Pacific and Air Facilities for International Police Force: Air Bases Required for use of an International Military Force (April 10, 1943),” cited in Eldridge, op.cit., 1999a, p.68.

26. Ibid., p. 70.

27. Kobayashi, op.cit., 12.

28. New York Times, March 29 and April 3, 1945; Gale, op.cit., p.52.

29. Gale, ibid., p.53; FRUS 1945, Vol. I, General: The United Nations, p.311-312.

30. “Japan: United States: Disposition of the Mandated Islands (CAD-335, preliminary, January 26, 1945)”, RG59, Records of Harley A. Notter, 1939-45, Records relating to Miscellaneous Policy Committees 1940-45, box 116, NA.

31. Ibid.

32. Ibid.

33. Ibid.

34. Ibid.

35. Ibid. This recommendation of international trusteeship was approved at the Inter-Divisional Area Committee on the Far East of State Department held on January 25, 1945, before the Yalta Conference, in State Department. (RG59, Records of Harley A. Notter, 1939-45, Records relating to Miscellaneous Policy Committees 1940-45, box 119, NA.)

36. FRUS 1945: The Conference at Malta and Yalta, pp.78-81.

37. Gale, op.cit., p.53.

38. Dorothy Richard, United States Naval Administration of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1957, v.3, p.13; Gale, op.cit., pp.54-55.

39. FRUS: The Conferences at Malta and Yalta 1945, p.859.

40. “Memorandum by the Secretaries of State, War, and Navy to President Truman, Washington, April 18, 1945”, FRUS 1945, Vol. I, pp.350-351.

41. Text of this draft (the 16th draft of US proposals for trusteeship made since the beginning of interdepartmental consideration early in 1945) was adopted by the US delegation at its nineteenth meeting on April 26. After clearance by telegraph with the War and Navy Departments copies were transmitted to the Acting Secretary of State by tele¬gram on April 27, and to President Truman in memorandum of May 1.

42. (Article 43) “1. All Members of the United Nations, in order to contribute to the maintenance of international peace and security, undertake to make available to the Security Council, on its call and in accordance with a special agreement or agreements, armed forces, assistance, and facilities, including rights of passage, necessary for the purpose of maintaining international peace and security.; 2. Such agreement or agreements shall govern the numbers and types of forces, their degree of readiness and general location, and the nature of the facilities and assistance to be provided.; 3. The agreement or agreements shall be negotiated as soon as possible on the initiative of the Security Council. They shall be concluded between the Security Council and Members or between the Security Council and grounds of Members and shall be subject to ratification by the signatory states in accordance with their respective constitutional process.”

43. The Charter of the United Nations, Scranton, Pennsylvania: The Haddon Craftmen, 1945, pp.196-199. Underlined by author.

44. Scholarly Resources, Inc., Microform Publication: U.S. State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee, Policy Files, 1944-1947, Microfilm Roll No.8, NA.

45. The UK placed Tanganyika, the Cameroons and Togoland under trusteeship. So did Australia for New Guinea, Belgium for Ruanda-Urundi, and New Zealand for Western Samoa. Nauru became a trust territory jointly administered by the UK, Australia and New Zealand. France agreed to place its portions of Togoland and the Cameroons under trusteeship as well. Somaliland was an Italian trust territory.

46. Walter Millis (ed.), James Forrestal, The Forrestal Diaries, New York: Viking Press, 1951, p.216, p.130-131; Gale, op.cit., p. 56.

47. Gale, ibid., p.56-58. Kobayashi, p.14.

48. (JCS570/5-SWNCC249/1) JCS1619/1, p.23; SWNCC 59/2, p.49, Microfilm LM54 Roll 8, NA. [“Nansei Shoto” is the chain of islands located south-west of the Japanese main islands, stretching between Kyushu and Taiwan. “Nanpo Shoto” is another chain of islands located south of mainland Japan, and north of Micronesia.