Henoko, Okinawa: Inside the Sit-In (Japanese Original Text at Peace Philosophy Centre)

Kikuno Yumiko

Translation by Norimatsu Satoko and Kikuno Yumiko

Introduction by Norimatsu Satoko

On the rainy and cold Christmas Day of 2009, we got lost several times driving down the winding narrow roads towards Henoko, a small fishing village on the North Eastern shore of Okinawa Island, about a two-hour drive north of the capital, Naha. We were looking for the “Tent Village,” where activists were sitting in to protest against the government’s plan to build a new US Marine Corps airbase as a “replacement facility” of Futenma Air Station. Yes, this issue has been at the centre of the news reports in Japan for the six months since the new coalition government took power, but do we really know what has happened for the last eight years in and around this tent, on and off this coral beach, and in the ocean where endangered marine mammal dugongs come by for feeding? The victory of Inamine Susumu, the anti-base candidate in the January 24 mayoral election of Nago, where Henoko is located, was anticipated but was not known yet when the 40-minute lesson on the history of Henoko activism was given inside the tent to two visitors from the mainland and from overseas. Thinking back, the protesters at Henoko were among the citizens of Nago and Okinawa who served as advocates of democracy during the thirteen years of chasm between the pro-base government of Nago and the popular will opposing the new base, expressed in the 1997 plebiscite. In the Western world, the sit-in by the workers of Gdansk shipyards is well-known as one of the longest in modern times, and one that launched the transition to democracy in Poland and helped end the Cold War. But the multi-year Henoko “sit-in” story is little known outside of Japan, if not outside of Okinawa. Here is the first short account from “inside” the movement by one of its stalwarts.

Okinawa used to be the independent Ryukyu Kingdom, blessed with a bountiful environment and friendly trade relations with many other Asian countries. In March 1609, Satsuma-han (now Southern Kyushu Island) invaded the Ryukyu Kingdom. In 1879, the Meiji Government forced the Kingdom to surrender Shuri Castle by means of the “ Ryukyu Disposition,” which brought down the curtain on the Ryukyu Kingdom. Ryukyuan culture was subsequently lost under the assimilation policy of the Japanese government. Towards the end of the Asia-Pacific War, war was forced upon Ryukyu Islanders in the Battle of Okinawa, in which 200,000 lives were lost, including over 90,000 local civilians who were killed or forced to commit suicide. Today, Okinawa is burdened with 75% of all U.S. military bases in Japan. It seems so unfair that the Ryukyu Islands have had to endure such a tragic history. I want to bring my heart closer to Okinawa and its people, especially in light of the “Futenma Base Transfer” controversy.

On December 25, 2009, I visited “Henoko Tent Village” in Okinawa, with Satoko Norimatsu, Director of the Peace Philosophy Centre, a peace education centre in Canada. The “village” has acted as a base for the 13-year long nonviolent anti-base movement. On the day we visited it was raining, which made Henoko beach look like it was crying. We were welcomed by Toyama Sakae, the “mayor” of Henoko Tent Village, and by other activists, including Nakazato Tomoharu, “Yasu-san,” and “Na-chan.” Mr. Toyama invited us to have a seat and proceeded to explain the history of the movement to save Henoko.

The Tent Village “Mayor” Toyama Sakae explains the history of protest at Henoko. Toyama is pointing at the “V-shaped Runway Plan” in the 2006 agreement between Japan and U.S. officially described as a “replacement facility” of Futenma Air Station.

In 1995, the rape of a 12-year-old Okinawan girl by three U.S. Marines triggered a huge anti-base movement throughout the Islands of Okinawa. Then in 1996, Japan and the United States agreed to the plan put forward by the Special Action Committee on Okinawa (SACO), which stipulated that the Futenma Air Station would be relocated to Henoko, on the East Coast of Northern Okinawa, in an attempt to appease Okinawans angered not only by the rape but above all by the heavy U.S. base presence in the densely populated South. The following year, in 1997, residents of Henoko started an organization called “Inochi o mamoru kai,” “the Association for Protecting Life.” They began a campaign opposing the effort to establish a new U.S. base at Henoko. The majority of Nago citizens also voted against the agreement, in a referendum held that same year. However, the Mayor of Nago at that time accepted the plan. These events marked only the beginning of what has been a long and unfinished struggle in Henoko.

The Tent Village on the Henoko Shore. It was day 2,077 of the sit-in when we visited.

Success in stopping plan to build an offshore U.S. airbase

In 2002, the Japanese government decided to construct a 3,000 meter-long U.S. air station two kilometers off the coast of Henoko. If this new U.S. base were to be built, the beautiful view from Henoko of the horizon over the ocean would disappear entirely. On April 19, 2004, the Naha Defense Facilities Administration Bureau (DFAB) tried to proceed with construction, but approximately 70 people erected a sit-in human barricade to keep dump trucks from passing through. At 5 a.m. on September 19, 2004, approximately 400 activists gathered and prepared for a confrontation with riot police. The DFAB learned of the sit-in and decided to access the site by going through Camp Schwab, chartering fishing boats from Henoko fishermen (whom they paid exceedingly well), and setting out to sea rather than risk confronting the barricade.

Protesters being briefed on the day’s activities in the tent village, in March 2005

The battle subsequently moved from land to sea. The anti-base activists attempted to stop the DFAB from setting up scaffolding towers to conduct the drilling – their plan being to drill at a rate of 63 borings per year. The activists set out to sea in canoes, surrounding the buoy markers, an hour before the construction workers started their workday. Despite repeated attempts over a two month period to halt underwater surveying, four towers were completed. After that, some activists took to wrapping their bodies with a chain and locking themselves to the motor set on the top of the tower in an attempt to interrupt the operation. In the course of this resistance some of the protesters, including one woman in her fifties, were pushed off the top of the scaffolding tower and were injured.

In November 2004, about 20 neighboring fishing boats joined the protesters. This support was a big help in interrupting the drilling. Activists in their fishing boats and canoes had to maintain a presence around the scaffold tower from 4 a.m. to 5 p.m. They covered themselves with straw mats to keep warm on the frigid waters. It was especially hard for women to spend long hours on the ocean without going to the bathroom, so they often participated without consuming any water.

A protester’s ship approaching one of the scaffolding towers, July 2005

DFAB commenced night shifts starting in April 2005 and since that time, protesters have had to spend 24 hours a day hanging on to the towers. Activists are unable to leave the towers even for a minute, for if they do, DFAB crews would jump in and start working. Activists, consciously adhering to the principle of non-violent civil disobedience, have ensured they are already in place each day before DFAB crews arrive in order to avoid an altercation. At one point, activists remained on the towers for a 50 day period, alternating two 12 hour shifts. In the mean time, other anti-base organizations within Okinawa visited the Naha DFAB office many times in an attempt to convince officers to cease night-time operations, which posed a danger to DFAB workers and protesters alike. Night shifts were also keeping dugongs away from their feeding area. As a result of the protesters’ unwavering campaign, the Government finally abandoned the plan to build an offshore air station on October 29, 2005. The number of people who participated in the campaign totalled 60,000, including 10,000 who protested at sea.

Henoko suffering more from new Japan-U.S. agreement

On October 29, 2005, Japan and the U.S. agreed on a new plan to build a 1,800 meter-long runway inshore from Henoko, partially on the peninsula, instead of entirely offshore. This time even the Mayor of Nago and the Governor of Okinawa, who had both supported the offshore base, opposed the plan, noting that it would be located a mere 700 meters from a residential area. However, in April 2006, Nukaga Fukushiro, Japan’s Defense Agency chief at the time, told Nago mayor Shimabukuro Yoshikazu about yet another new plan, this time to build a V-shaped runway. Nukaga explained that one side of the runway would be used only for landing and the other side only for taking off. This plan would be safer, Nukaga insisted, because fighter planes would not fly over residential areas. In the end, the Defense Agency chief prevailed and the mayor of Nago green-lighted the V-shaped runway. However, according to Toyama, military flight training mostly involves what is known as “touch-and-go” landing — landing then immediately taking off without coming to a full stop. This is the way the Marines have been training at Futenma Air Station. Likewise, a U.S. official document states that they wouldn’t necessarily restrict use to one side of the V-shaped runway for taking off and the other for landing. The opponents of the base suspected that the true motive for the V-shape plan is that it would allow training to occur regardless of wind direction. When the opposition parties questioned the Japanese government about this at a Diet session, the answer was “It will be possible to use both sides of the runway for taking off, depending on what type of training is being conducted,” thereby contradicting their original argument. Mr. Toyama and his colleagues informed Nago City about this Diet exchange and requested that the City rescind its approval of the V-shape runway, but to no avail.

Protesters receive instruction on canoe handling, May 2007

In April 2007, it was decided that Naha DFAB would begin an environmental assessment of the area where the V-shaped runway would be constructed. The activists pointed out that this particular assessment procedure was in violation of the Environment Impact Assessment Law. The law requires that an actual construction schedule for a major project such as the runway can only be decided after an assessment has been made, whereas in this case, a completion date of 2014 had already been set before any assessment had been started. Such a procedure was in clear contravention of the Assessment Law. To conduct the survey, some 120 pieces of equipment would be set in the water, including 30 passive sonars, 14 underwater video cameras, and machines used to check the adherence of coral eggs and ocean currents.

On May 18, 2007, the first day of the survey, the Japanese government sent the Maritime Self-Defense Force minesweeper tender “Bungo” to Okinawa in order to stop the protest activities. It was unprecedented for the Self-Defense Force to be introduced against a civil protest. Then Defense Agency chief Kyuma Fumio ordered that working ships be reinforced and increased Japan Coast Guard officer-bodyguards from 30 to 100. At the time, Kyuma was reported as saying, “I don’t want to repeat that frustrating experience of 2005 when we had to give up the construction of an airbase offshore Henoko.” As a result, Japanese Coast Guard vessels, thirty working ships and sixteen rafts, anchored offshore from Henoko, reminiscent of the U.S. Fleets that surrounded Okinawa Island during the Battle of Okinawa. Against such an armada, there was little the protesters could do. They were held up by the Japan Coast Guard for nearly three hours almost every day, and at one point, several workers of the government agency came to remove an activist who had dived underwater beneath some of the equipment. In the end, most equipment was installed despite the life-risking protests.

Early morning on May 18, 2007, protesters on canoes set out to the sea, trying to stop the Defense Bureau’s assessment. It was the morning of the unprecedented Maritime Self-Defense Force dispatch of a minesweeper to suppress the civil protest.

The Henoko activists know that they can’t completely thwart the government’s survey, but they continue their land-based and maritime actions, hoping to interrupt and delay the survey to buy time until the Nago mayoral election (January 2010) and the Okinawa gubernatorial race (November 2010). Mr. Toyama said, “Following the survey, the Naha Defense Bureau has to apply for a reclamation permit, and this requires approval by the prefectural governor. If a candidate opposing the base construction wins the next gubernatorial election, we will be able to stop the base construction plan. That’s the kind of vision we hold as we continue our protest.”

Mr. Toyama also told us about environmental concerns the likes of which we have never heard before. Twenty-one million cubic meters (2,100,000 ten-ton truckloads) of sand will be needed to reclaim 160 hectares of land from the sea for the proposed construction. The government agency would have to exploit most of the sand along the East Coast of Okinawa, as well as cutting down thirty hectares of trees around Henoko Dam in order to dig out two million cubic meters of soil and gravel. The Dugong would die out because the sea grasses that they feed on would be destroyed, and the Henoko Dam would be unable to supply enough clean water to residents. Naha DFAB explained the area was a convenient place to extract soil and gravel quickly and reliably. Mr. Toyama said, “We have been told that the new U.S. base is necessary for our security, but this plan will threaten that very security because it will ruin even our drinking water.”

Members of “Inochi o mamoru kai,” the Association for Protecting Life, in the Tent Village, February 2010

Future prospects

In terms of the political aspect, Mr. Toyama explained, “The three ruling parties [DPJ, SDP, People’s New Party] are reviewing the U.S. military realignment plan in order to lessen the burden of Okinawans, and I feel hopeful about their consideration of a place other than Henoko for relocating Futenma. The current [Hatoyama] government expressed opposition to the Henoko relocation before the Lower House election last year. If instead they apply for the reclamation permit as planned for April 2010, they would be contradicting themselves and be left without a leg to stand on. In the last election of the House of Representatives, candidates opposing the new base construction won all four election districts in Okinawa, so I expect the trend will continue into the upcoming Nago mayoral election and the Okinawa gubernatorial race in 2010.” He added, “The construction industry occupies a large portion of secondary industry in Okinawa and most of the base supporters are subcontractors who are given public works contracts by the big general construction companies, such as Mitsubishi. However, seventy-percent of Okinawans oppose construction of a new base in Okinawa and only fifteen percent approve it.” In terms of the environment, the U.S. District Court in San Francisco ruled in 2008 that the U.S. base construction plan in Henoko violated the National Historic Preservation Act of the United States. Although this judgment did not require withdrawal of the plan, it ordered the U.S. Department of Defense to provide environmental protection measures. Hopefully this decision will have an impact on the actions of the U.S. government.

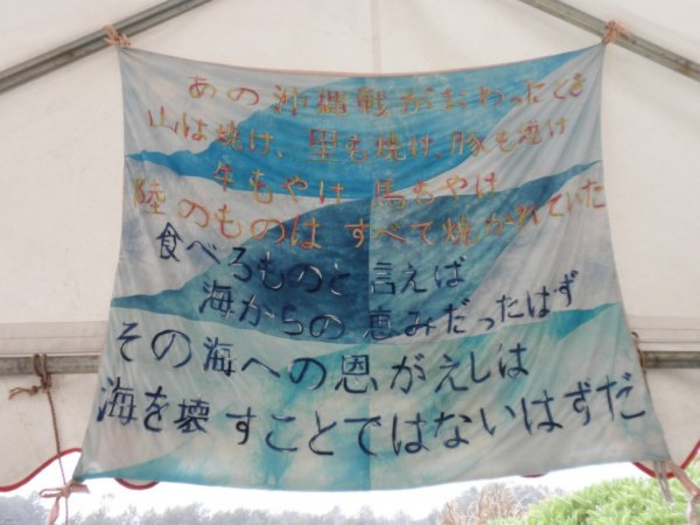

While listening to Mr. Toyama’s explanation, I heard the creaking sound of the pipes that supported the tents. It sounded like the painful cries of Henoko. I looked around inside the tent and found a large tapestry that read:

“At the end of the Battle of Okinawa,

Mountains were burnt. Villages were burnt. Pigs were burnt.

Cows were burnt. Chickens were burnt.

Everything on the land was burnt.

What was left for us to eat then?

It was the gift from the ocean.

How could we return our gratitude to the ocean

By destroying it?”

400 years after the Japanese invasion of the Ryukyu Kingdom, have we ever listened to the voices of Okinawa? Have we ever truly understood their suffering? Have our hearts ever reached out to the 13-year long struggles in Henoko? I said to myself, “I am sorry for Henoko… and Okinawa…We won’t let another military base be built in Henoko or anywhere else in Okinawa.”

Many thanks to Mr. Toyama and the other activists in the Tent Village for giving us such a thorough explanation of the situation.

Author Kikuno Yumiko on Henoko Shore. Beyond the border is Camp Schwab. Barbed wire is decorated with strips of colourful cloth with messages for a base-free Okinawa by visitors to Henoko.

We thank Miyagi Yasuhiro for his advice on content, Blog “Chura umi o mamore” and Blog “Henokohama Tsushin” for permission to use photos from their sites.

Kikuno Yumiko is Editor of “U-Yu-Yu,” a community journal based in Miyakonojo, Miyazaki, and works for the city’s community revitalization project.

Norimatsu Satoko leads various peace initiatives in Vancouver and beyond, including, Peace Philosophy Centre and Vancouver Save Article 9.

The introduction and translation were prepared for the Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: Kikuno Yumiko and Norimatsu Satoko, “Henoko, Okinawa: Inside the Sit-In,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 8-1-10, February 22, 2010.

See the following related articles on the Okinawan anti-base struggle:

Urashima Etsuko and Gavan McCormack, Electing a Town Mayor in Okinawa: Report from the Nago Trenches.

Iha Yoichi, Why Build a New Base on Okinawa When the Marines are Relocating to Guam?: Okinawa Mayor Challenges Japan and the US.

Tanaka Sakai, Japanese Bureaucrats Hide Decision to Move All US Marines out of Okinawa to Guam.

Gavan McCormack, The Battle of Okinawa 2009: Obama vs Hatoyama.

Miyume TANJI, Community, Resistance and Sustainability in an Okinawan Village: Yomitan.

Hideki YOSHIKAWA, Dugong Swimming in Uncharted Waters: US Judicial Intervention to Protect Okinawa’s “Natural Monument” and Halt Base Construction.