Katarzyna Cwiertka

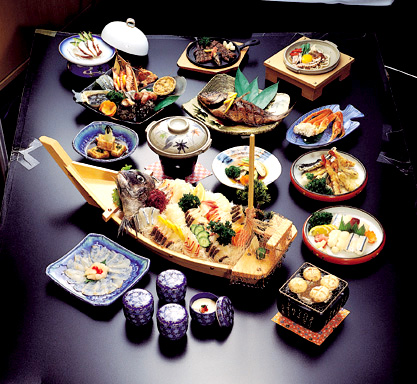

During the last two decades, Japanese food succeeded in penetrating a wide spectrum of global gastronomy. From posh dining through healthy meal to a quick bite, Japanese cuisine is present in practically every niche of the ever diversifying restaurant market. While classic establishments proudly dish up kaiseki menus for the connoisseurs of exclusive dining, teppanyaki steak-houses provide culinary entertainment to those with less privileged taste buds, and sushi and noodle bars appeal to young customers.

Equally spectacular has been the growth of publications in English concerning Japanese cuisine. Along with conventional cookbooks and guidebooks on how to order in Japanese restaurants, other genres of culinary writing on Japan are thriving as well. Current bestsellers, such as Sasha Issenberg’s Sushi Economy and Trevor Corson’s The Zen of Fish – both dealing with sushi boom in the US – appeal to broad audiences obviously fascinated with the cultural, social and historical backgrounds of recent culinary trends.

Books on Japanese cuisine sell particularly well due to an aura of exoticism and revered traditionalism that surrounds them. Cooks and publicists cultivate the image of Japanese cuisine as refined craftsmanship that had been handed down, practically unchanged, from generation to generation. A recent initiative of Japan’s Agriculture Ministry to inspect and certify Japanese restaurants abroad (which came to be known in popular jargon as the ‘sushi police’) vividly illustrates its eagerness to perpetuate the myth of Japanese culinary tradition.[1]

However, if contemporary Japanese cuisine was to be labelled at all, ‘multicultural’ and ‘innovative’ would, in my opinion, be much more appropriate terms. That the economic prosperity of the last few decades is largely responsible for the abundance of food choices in Japan seems obvious. Greater disposable income made formerly expensive and exclusive types of food widely affordable and, moreover, created opportunities for ordinary Japanese to embrace foreign tastes and global culinary trends. However, the culinary multiculturalism dates back several decades further. It was part and parcel of the culinary transformation of modern Japan that can very generally be described as the making of Japanese national cuisine, a set of foods, tastes and practices that most Japanese today ardently identify with. A persistent homogenization of local food practices and attitudes into a national standard, although not a goal in itself, was the major outcome of this process.

Japanese national cuisine was shaped by a variety of forces that emerged in Japan since the late nineteenth century. However, perhaps surprisingly, militarism stands out as the most powerful. This influence of militarism does not complement the general image of Japanese cuisine, with its strong emphasis on aesthetics of presentation and harmony with nature, and is therefore very little known.

As elsewhere, modern armed forces played a critical role in turning the inhabitants of the Japanese isles into a nation. [2] The conscription experience confronted young Japanese farmers with objects, practices, and opinions that they would otherwise have had little opportunity to encounter. This holds as true for diet as it does for the custom of smoking cigarettes or inculcation of patriotism. Military menus reinforced the spread of the ideal of rice as the centrepiece around which a meal was constructed, and of soy sauce as a key flavouring agent. These had originally been the characteristic features of the meal pattern of the upper classes and the urban population, still a minority of the Japanese population even in the early twentieth century. The majority – mostly peasants – relied on other staples, or perhaps on a mixture of rice with vegetables and other grains. Peasants customarily flavored their food with home-made soybean paste (miso), while soy sauce, either home-brewed or purchased from commercial brewers, was reserved for special occasions. Thus, by virtue of conscription, the sons of farmers enjoyed the new ‘luxury’ of being sustained by menus that would have been considered too extravagant for daily consumption back home.

Furthermore, a military canteen was for thousands of drafted peasant sons the site of their first encounter with multicultural urban gastronomy. During the 1920s, when the army reorganized its menus, it introduced meat-based and deep-fried dishes that at the time appeared almost exclusively on the menus of Chinese-style and Western-style urban eateries. These hybrid dishes were designed to provide conscripts with sufficient calories at relatively low cost. They were not only hearty, relatively inexpensive and convenient to cook in large quantities, but also unknown to most soldiers.

Recruits hailed from all over the country and they had been used to different kinds of food. For example, during the experiments conducted by a prominent staff member of the Army Provisions Depot, Major-general Kawashima Shiro (1895–1986) in winter 1936/1937, 22 per cent of soldiers who participated in the experiment found the miso soup served too sweet, while 10 per cent found it too salty. Military cooks had problems making the food suit the taste preferences of the majority of soldiers and sailors and tried to overcome regional differences in diet by including local dishes, such as miso soup with pork, vegetables and sweet potatoes (satsumajiru) from southern Kyushu or kantoni, (today better known as oden) from the Tokyo region, in the military menus. However, curries, croquettes and Chinese stir-fries introduced on a large scale during the 1920s turned out to be the best solution for making the taste of military menus agreeable to the majority of conscripts, since at the time the men were still equally unfamiliar with Western and Chinese food. By serving foreign foods that were new to all recruits, army and navy cooks not only helped to level regional and social distinctions in the military, but also speeded up the process of nationalizing and homogenizing food tastes in Japan.

The extensive reforms of army catering that took place during the 1920s involved not only the alteration of menus, but also the introduction of modern cooking equipment, such as meat grinders, vegetable cutters and dish washers that helped economize on labour. Furthermore, a new educational program for army cooks was launched and practical implementation of the disseminated knowledge was constantly monitored. Soon, army kitchens were propagated as the example to follow by civilian canteens at schools, factories and hospitals. The model continued to be reproduced in restaurants and civilian canteens, where former military cooks and dieticians found employment after 1945. Gradually, the military connotations of the food faded and the innovations implemented by the armed forces were amalgamated into the mainstream civilian culture of the post-war era.

By the time the Sino-Japanese War (1937-45) broke out, the efficiency-driven military models were being rapidly extended beyond mass catering to encompass practically every individual. The advertising campaign for ship biscuits (kanpan), launched in 1937, vividly illustrates the intricate connections between the military, the food industry and public nutrition in wartime Japan. Kanpan had been the staple in the Japanese armed forces for decades, but before 1937 remained largely unknown to civilian consumers. Approximately 90 per cent of total biscuit production in Japan at the time was constituted by products other than kanpan, but by 1944 the ratio was reversed. The new product was widely advertised, often carrying patriotic texts that called for solidarity with the soldiers at the front. However, it was the multi-faceted efficiency of kanpan, rather than its military imagery that assured its dissemination among the civilian population. It provided three times more calories than rice (which became increasingly scarce); it was easy to store and transport; and it was ready-to-eat. The last point was particularly important, since by the 1940s fuel for cooking was rationed and the confiscation of scrap metal, needed for the production of airplanes, tanks and other frontline necessities, deprived many households of cooking equipment.

The wartime mobilization of people and resources, which was successively tightened as the war continued, had an unprecedented homogenizing impact on Japanese cuisine. As the fixed components of the urban landscape, such as public transport, cinemas, department stores and restaurants one by one disappeared under the pressure of mobilization for total war, urban life increasingly came to resemble rural existence. Every free space in the cities – schoolyards, river banks, parks, and later also bombed out areas – was turned into vegetable gardens in order to supplement food supply. The divide that had for centuries separated the rural and urban diet rapidly declined.

The rationing of rice, introduced in 1941, was critical in this respect. On the one hand, since rice rations alone were insufficient, rationing forced urban consumers to rely more on staples other than rice, including tubers grown in their emergency gardens. On the other hand, it entitled peasants and other social groups that previously could not afford rice to its more regular consumption. In other words, the rationing had the enduring effect of singling out rice as the national staple, granting all Japanese the right, even if only in theory, to a rice-centered diet. This experience provided a firm foundation for the regional and social homogenization of Japanese cuisine during the 1950s and ’60s.

Japanese militarism and imperialism continued to shape Japanese foodways even after the fall of the regime in 1945. More than a million Japanese who resided in Korea, Taiwan, Manchuria, China and other territories under Japan’s domination acquired a taste for foreign food and played a critical role in its popularization in post-war Japan. For example, returnees from Manchukuo were responsible for the dissemination of northern Chinese dishes, such as gyoza dumplings. Needing to create jobs for themselves, many began making and selling gyoza to hungry customers. Gyoza were particularly suited to the circumstances of the late 1940s, since they were made of wheat flour, which was easier to acquire than rice, and practically anything qualified as stuffing. At approximately the same time, Koreans sold grilled tripe and offal at stalls in black markets. Since the 1920s Koreans had migrated in great numbers from the colony, and several hundred thousand were drafted as forced laborers in Japan during the war. Most were repatriated shortly after 1945, but more than half a million remained, constituting the Korean community in postwar Japan. When the rationing of meat was lifted in 1949, grilled meat gradually replaced offal on the menus of these stalls and eateries run by Koreans. The yakiniku restaurants so ubiquitous all over Japan today are their direct descendants.

These examples alone vividly demonstrate that militarism and war were not merely agents of destruction, but have also served as catalysts of innovation. The legacy of war and empire directly shaped Japanese cuisine and dietary practices, not to mention their long-term impact on agricultural production of food, its distribution and processing. This chapter of Japanese history is no less relevant to the culinary culture of contemporary Japan than Edo gastronomy that had given birth to the sushi culture.

It goes without saying that the construction of Japanese national cuisine that began with the political reforms of the Meiji period (1868-1912) was deeply embedded in the existing environment and relied on knowledge, skills and values that the Japanese people had accumulated over the centuries. Many of the constitutive elements that today stand for culinary Japaneseness do have deep historical roots. However, it was the process of nation building, largely sustained by imperialism, expansionism, and post-war economic affluence that shaped the outcomes that we know today as Japanese cuisine.

Notes

[2] See, for example, Eugen Weber, Peasants into Frenchmen: The Modernization of Rural France, 1870-1914 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1976).

This article, written for Japan Focus, draws on the author’s Modern Japanese Cuisine: Food, Power and National Identity. Posted at Japan Focus on July 20, 2007.

Katarzyna Cwiertka is Lecturer at the Centre for Japanese and Korean Studies at Leiden University , and specializes in social history of modern Japan and Korea with particular focus on food and cuisine.