Rokkasho, Minamata and Japan’s Future: Capturing Humanity on Film

Kamanaka Hitomi, Tsuchimoto Noriaki and Norma Field

Translated by Ann Saphir

In this first decade of the twenty-first century, nuclear weapons and nuclear power have returned to haunt us with a vengeance. In fact, they had never disappeared, of course, but the end of the Cold War and a hiatus in the construction of nuclear power plants—owing much to citizen activism, let us recall—lulled many of us into putting these concerns on the backburner. Now, thanks to 9.11 and newly visible

It is just such a reprocessing plant, completed in

From Hibakusha at the End of the World

In the dialogue translated below, Kamanaka and Tsuchimoto Noriaki, the celebrated documentarist of Minamata, discuss such issues as radiation and Minamata mercury poisoning, the history of activist documentary film-making and screening in Japan, the relationship between formal matters of narration and subtitling to political stance, and questions of partiality, trust, and usefulness to a cause. Like her predecessors, including Tsuchimoto and Ogawa Shinsuke, the documentarist of the

Such reflection is being generated throughout

The issues of nuclear power and nuclear weaponry are never far apart for Kamanaka herself. In the course of a discussion at the University of Chicago during her April 2007 visit for the U.S. premiere of Rokkasho Rhapsody, Kamanaka disclosed that she herself had been affected by her exposure to DU in Iraq, specifically during the December 1998 bombing of Baghdad known as Operation Desert Fox (just prior to the Clinton impeachment), after which she contracted cancer. Though diffident about claiming the identity of hibakusha for herself, she has consented to having this biographical detail shared more widely in the hopes that US soldiers might be alerted to their own symptoms. [2]

Norma Field

[1] For a

[2] Rokkasho Rhapsody is not yet available for distribution in the

A podcast of Kamanaka’s discussion with documentarist Judy Hoffman and film scholar Michael Raine following the screening of Rokkasho Rhapsody is available at this website.

A transcription of Kamanaka’s classroom discussion with Dave Kraft of Nuclear Energy Information Service, including her discussion of her DU exposure and cancer, may be found together with other materials gathered for the Celebrating Protest series at the

One of Kamanaka’s interlocutors in

Development and Pollution: Capturing Humanity on Film

A Conversation Between Tsuchimoto Noriaki and Kamanaka Hitomi

Matsuura Hiroyuki (Moderator): The issue of low-level radiation depicted in Ms. Kamanaka’s film, Hibakusha — At the End of the World, is in many ways a replay of the problematic pattern of Minamata disease on a more global level. The structural aspects of the issue also remind us of Director Tsuchimoto’s series of works on Minamata.

Low-level radiation and Minamata disease have many points in common. In both, the body is sickened with an “invisible poison” spread through the environment through human means; in both, the poison is absorbed through the food chain into the body, where it accumulates; “science” and “data” obstruct efforts to aid and compensate the victims; and both involve regional economic issues linked to the lives of local people.

In addition to works on Minamata disease, Mr. Tsuchimoto pioneered films that fostered a public awareness of the danger of Japan’s nuclear policies, such as A Scrapbook About Nuclear Power Plants (1982) and Umitori–Robbing of the Sea: Shimokita Peninsula (1984), as well the problems of “regional development.”

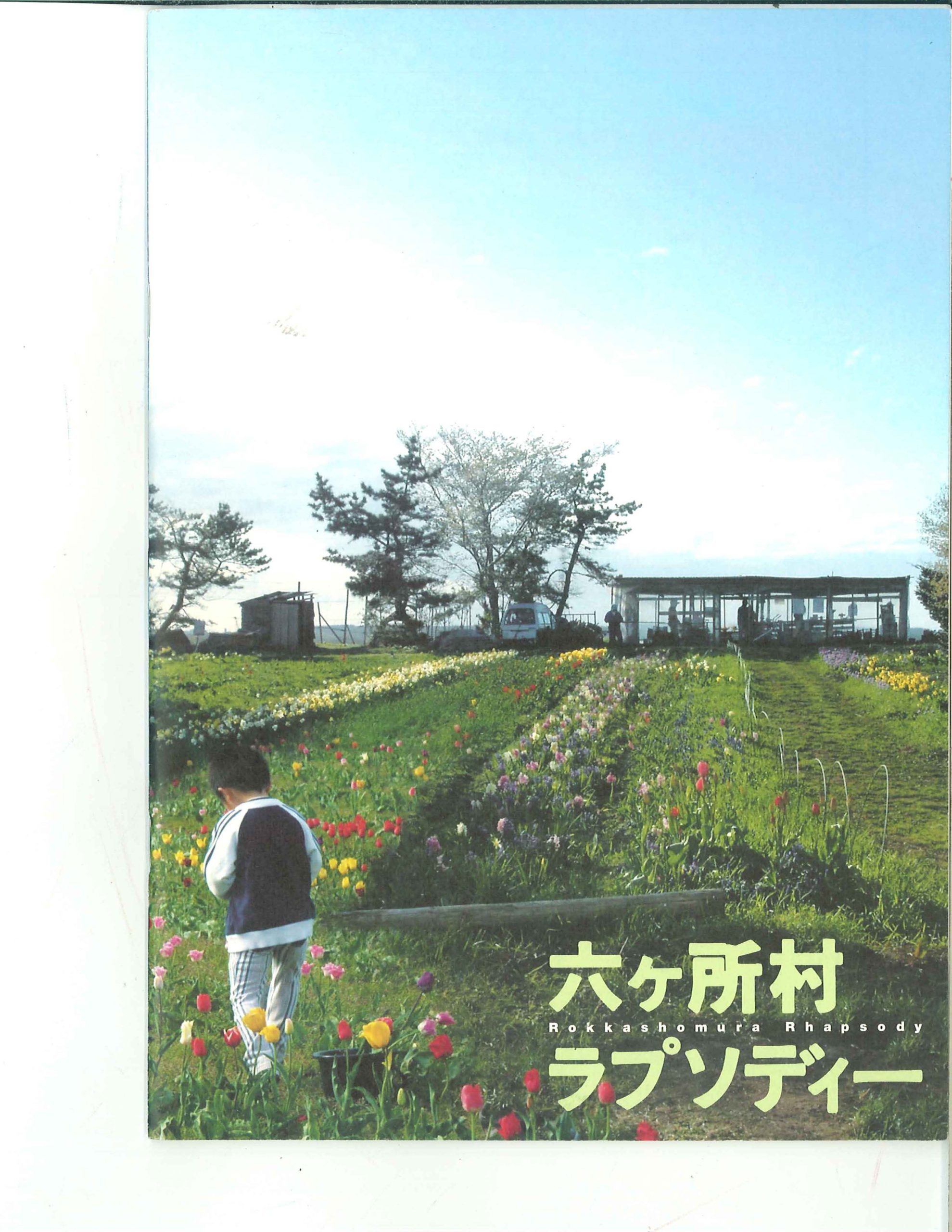

Ms. Kamanaka is taking up the issue of Rokkashomura’s nuclear reprocessing plant in her new work, Rokkashomura Rhapsody [released 2006].

These two documentarists from different generations will speak freely about their thoughts and impressions with regard to their work and documentary film in general.

Issues in Trace Intake and Low-Level Radiation Exposure in Minamata, Rokkasho, and

Tsuchimoto: Mr. Matsuura said that low-level radiation presents the same issues as Minamata, and that’s absolutely so. The problems of low-level radiation exposure also relate to the future of Minamata. If you were to represent the numbers of victims with their symptoms as a pyramid, it doesn’t exactly fit the pattern where the critically ill form the apex and the base is a broad gray area. It wouldn’t exactly be wrong to say that, but in reality the base is broad and messy.

Early on it was understood that the main contaminated fish were sardines and swordfish, as well as squid and octopus and shellfish. But recently the problem has been associated with long-lived ocean fish. There’s not much effect on the body if you eat a fish that’s only lived for a half a year or a year. But the longer a fish lives, the more mercury is accumulated in its body. So if it’s a fish that’s lived longer than about three years, it comes out very clearly in the numbers. Mercury pollution is getting worse in many parts of the world’s oceans. That’s because of the relationship between mercury on the one hand and industrialization and widespread use of chemical fertilizers on the other.

Even in

I used to think that after witnessing Minamata disease, humankind would have learned a lesson. But if you look at where the world’s mercury levels have gone since, it’s clear that’s simply wrong. Mercury is an extremely useful substance that’s used as a catalyst in liquid, gas or solid form. In the Amazon and such places it is used to process gold, and gold is used a lot in cell phones.

KAMANAKA: That’s right. Precious metals are used in cell phones, though in very small amounts. I don’t know how we can dispose of all those cell phones.

TSUCHIMOTO: That’s why I think your film shows how the problems of low-level radiation exposure and disposal of trace amounts are new additions to the horror of the atomic bomb. I think this is a very farsighted message. Researchers have known about it. But we are the only ones to communicate it.

KAMANAKA: While scientists have said for the last fifty years that it’s fine if it’s only a small amount [of a toxic substance], your Minamata films opened my eyes to the fact that even a small amount is dangerous. It was Minamata that showed us images of how mercury is concentrated in the body and goes to the brain and the nervous system of the fetus, and how chemical substances work in nature. Despite how myths around trace intake have been punctured in Minamata, I realized our society had not yet caught up.

TSUCHIMOTO: And we have dioxin that was spread through the defoliants used in the Vietnam War. That kind of thing is inexcusable on the part of the

KAMANAKA: That is what I feel is most difficult. Among film people, there are some who say dismissively, “This is a documentary film that accuses XYZ,” but the point of Hibakusha is not to make accusations. It’s not that scientists are wrong, or politicians are wrong, but rather that we who are supporting the situation must give it some thought. That’s it in a nutshell: I have to be able to provide something that the audience can understand with their brains but that also creates such an acute sense of awareness that they begin to say to themselves, “We can’t let things go on like this” – that’s what I want to be able to get them to feel.

TSUCHIMOTO: Along those lines, I’ve been thinking of something lately. I’ve been making films about Minamata for a long time, and the people who really start to think deeply about Minamata, even among those who have seen my movies, are those who have visited Minamata and met patients and had a chance to talk directly with them. Those are the people who are really taking full responsibility for the problem. I’m honored that my movies motivate so many people. But the current state of the information industry turns even useful information into products for consumption. The receiver thinks, “I already know this. I get it, and I feel done in.” But then, they don’t do anything. Because the information industry provides the answer—“You are not going to enter that kind of world, you want to live a different life”—and makes them feel relieved by alternating threats with flattery so that in the end, they don’t have to do anything. In other words, they have been sucked into thinking, “It’s okay as long as I’m comfortable; I won’t let my children get close to X or Y, I won’t go to any place like that.”

KAMANAKA: I think you have to be able to see the reality that you can’t escape by being like that. Because wherever you try to escape, it will come find you.

What’s hard about Rokkashomura is that no one has gotten sick yet. While there’s a buildup of radioactive materials, there aren’t any patients. The damage will take a while to appear, and even then, if it takes the form of an illness that anyone can get such as cancer or leukemia, it will be hard to prove that it’s caused by radiation. How do we make people recognize the harm caused by the power plant industry, that is, by radiation? It’s troubling, how hard it is to visualize getting to that point.

Rokkasho PR Center of Japan Nuclear Fuel, Ltd.,

owner-operator of the reprocessing plant

TSUCHIMOTO: And in Tokaimura, that nuclear chain reaction incident claimed two victims[1], but until the incident actually happened they had believed absolutely that nothing like that could ever occur. There’s maybe nothing you can do but keep your eyes on such examples. Once it’s visible on the outside, the problem has already become horrendous.

TSUCHIMOTO: You found your way to this subject while researching in

KAMANAKA: At the time we didn’t see why such low levels of radiation were affecting children’s health.

TSUCHIMOTO: This is something I heard from a doctor, but the human species has been exposed to many poisons in its hundreds of thousands of years of history, so there is apparently always a structure in the body that can protect you against, for instance, inorganic mercury. When I was young, I once watched sleepless for seven days and six nights from beginning to end as a friend lay dying after trying to commit suicide by drinking inorganic mercury. We should have made him drink eight or nine raw eggs to absorb the mercury and throw it up. And it’s the kind of poison that makes you want to vomit. In other words, people have learned a lot about such poisons.

In the human body there are barriers around the brain or the placenta through which poisonous materials structurally cannot pass. But with organic mercury it’s different. I think you will understand if you see the film, but, as with the patients who were affected as fetuses, it’s clear it passes through the placenta.

KAMANAKA: It violates the deepest part of the human species.

TSUCHIMOTO: It trashes the long history that’s gone into making the human body what it is.

KAMANAKA: And that’s where you can find one answer to the question of why such a small amount of a chemical substance made by humans would be so dangerous. As you know, organic mercury is a heavy metal. The radioactive substances of plutonium and uranium are also heavy metals. Because they are similar to naturally occurring minerals, the body can’t tell the difference. There are certain organs in the body in which minerals concentrate, like bones, for instance, that take up large amounts of calcium. Strontium 90, a radioactive substance, is very similar to calcium. So the body doesn’t know what kind of substance it is but mistakes it for calcium because it is similar, and so it goes ahead and absorbs it. Because strontium lodges in the bones and doesn’t dissipate, it just stays there and gives off radiation, harming the marrow and destroying the blood-production system and leading to leukemia.

Neither the government nor the mass media try to spread the word about a mechanism that is so simply described.

So even if people hear that radioactive substances are dangerous, if the local promoters of nuclear power don’t have that information and are told that the radiation from a plant is too little or too weak to matter, they are simply persuaded it won’t harm the body. I think there is a passive attitude on a subconscious level that lulls them into thinking it’s safe. Rather than stop using something because it’s dangerous, they want to believe it’s safe so they can keep using it.

TSUCHIMOTO: Many people are begging doctors and experts to say something’s “harmless,” that there’s “no possibility of trouble,” that it “should be safe.” There are few people who, if reassured by an expert, will continue to pursue it and ask, “Is that really true?”

KAMANAKA: That’s a point that really bothers me.

TSUCHIMOTO: All we can do is thoroughly introduce the issues under investigation by people like Harada Masazumi in Minamata and Dr. Hida in Hibakusha.

Something that struck me as very familiar when I saw Hibakusha was that doctors don’t speak clearly about cause and effect. Any doctor knows that you can’t definitively determine a cause and effect relationship between what you ate and your symptoms. All you can do is gather data that shows with depleted uranium, for instance, how many cases of leukemia there are in a given area, or how prevalent thyroid diseases are, or how common breast cancer is in women.[2]

In the recent Supreme Court ruling[3] on Minamata there are two critical points. In Minamata disease, numbness of the hands and feet is the most common symptom. Doctors say that numbness of the hands and feet could be from more than a hundred reasons. That’s true: my hands and feet are losing sensation because I am diabetic. So many patients cannot get certified or are rejected because it cannot be proven that their symptoms are from Minamata disease.

People would see that a patient might complain of numbness one day, but other days they wouldn’t have any numbness, and rumors would get started – they’re lying, they’re faking it. That was very hard on people with Minamata disease. There was nothing that could be done about those comments, either. Because they say there really are days when you feel tingling and others when you don’t. The real cause was in the brain. When one part of the brain is impaired by mercury, you get waves where it creates very serious numbness; by contrast, when you aren’t stressed, the numbness goes away. That was confirmed by the court.

And then there’s epidemiology. Whatever else you say, in areas where there are many patients, even people who stay healthy and are told they don’t have Minamata disease even though they’ve continued to eat the fish, they all tend to have serious symptoms like thyroid problems. Compare that to residents of other areas where they eat just as much fish as Minamata, for instance, in

That’s why in

KAMANAKA: There’s a specific history to the analysis of radiation poisoning. Data showing that there shouldn’t be any harm from exposure to radiation of less than a certain level of sieverts was calculated from the Hiroshima Model. So with depleted uranium, it is asserted that because the radiation level is low, there should be no damage.

TSUCHIMOTO: The issue is who says that.

KAMANAKA: That, of course, comes from the nuclear power industry. The International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) is seen internationally as the most authoritative organization, but they attach more importance to the impact of “external radiation exposure” where the body is bombarded by radiation from the outside. The impact of “internal radiation,” where the radiation comes from radioactive substances that have been taken up into the body, is given unfairly short shrift.

It is this ICRP’s recommendation — that it’s okay for the human body to be exposed to less than one millisievert a year — that led to the theory that depleted uranium munitions are okay because they come in below that level. But in reality, the facts contradict this “data.” If you look at it the other way, you have to come to the conclusion that internal radiation exposure can damage the human body at even lower doses. But based on decades of cumulative data, even if a few people in 100,000 got sick, for instance, the argument is that the benefits to society of using it take precedence.

TSUCHIMOTO: The idea that technological and industrial development should take priority is the worst product of 20th century thinking.

KAMANAKA: Here’s the logic: it would take this much money to reduce radiation contamination, and if you make businesses shoulder that burden their growth might be impeded. Imagine how it would be, for instance, if electricity rates went up and many people lost money. You might be led to say, maybe it can’t be helped that a number of people die. As long as we ourselves are not the victims, we close our eyes to the facts.

The Realities of High Economic Growth and “Local Development”

TSUCHIMOTO: Since the high economic growth period that began about 1955, the ideology of the survival of the fittest has been clearly evident in Japanese society.

I traveled often to Rokkashomura in the late 1950s and later in the early 1980s, and what everybody was afraid of back then was money. Around that same time I made a field trip to see the changes brought about by an industrial complex in Kashima in

There’s a terrific book called Untold “Development” — From Kashima to Rokkashomura (published by Henkyosha, distributed by Keiso Shobo, 1973). Do you know it? I think it’s out of print now, but the author, Ishikawa Jiro, worked in

An industrial complex was planned for Kashima, a remote area as far as

He did a lot of research and put it together to make this book. The book was extremely well read in some circles. One person from Rokkashomura, who at the time opposed the Mutsu-Ogawara development [4], said, “I want somebody like this to be a part of our group,” and invited him to join. He accepted and, without taking any money except to cover food and transportation, he came to live in Rokkashomura for a while. But then he was kicked out because of a difference of opinion with the progressive parties over elections.

I think that the Rokkashomura mayor at the time, Terashita Rikisaburo, understood in his bones the horror of money. The first job Mayor Terashita had after graduating from high school was at Chosen Chisso (a unit of Nippon Chisso Corporation, the predecessor company to the Chisso that caused Minamata disease). He was a factory worker, and he saw with his own eyes all manner of discrimination against Koreans. He was someone who could anticipate the horrors that would come with the influx of major capital to a village like his own, which he could see was as behind-the-times as a colony. So that’s why he wouldn’t budge an inch on “development.”

KAMANAKA: When I listen to the older men and women in Rokkashomura, they say , there’s nothing they can say to young people. Ask them why and they’ll say it’s because they need money. Long ago they didn’t need money. They would simply trade squid and vegetables. But that doesn’t work with today’s lifestyles. They want cars, they need to send their children to college, and everything costs money.

And with their way of life, money wasn’t coming in, so they couldn’t keep on as farmers and fishermen. This is what they say very clearly.

TSUCHIMOTO: In the short time span since the Meiji Period, I don’t think there is any place that has been as ruined as Rokkashomura.

Mategoya (fishing huts, no longer in use)

on Ogawarako, a brackish lake in Rokkasho

After the war, they began clearing land to make their living and in a little over a decade, talk of development projects would surface, construction companies would come swaggering in and if you showed the slightest interest, it would quickly become known, and rich people would buy up land on speculation. It was not just the state — it was the whole society that came to be like that.

KAMANAKA: It feels like the values that are important for human beings are always tripped up by money. I saw it in small increments as I gathered my materials. Fathers would go to the city in the winter as seasonal workers because they couldn’t make enough money with just fishing or farming. When that happens, it’s the mother who raises the children and keeps the home together. Fatherless families emerge and family life falls apart. The father’s in

The family that should come together to face the world and protect the household is already destroyed. The father is no more than the money he sends back. So when even more money becomes available, the things that are the most important are easily given up, is what I think.

When I saw your film Umitori—Robbing of the Sea:

A wilderness of land caused by money. I am sure the land that used to be called the periphery was rich once. There is the “smell” of richness. But they threw all that away.

TSUCHIMOTO: And they have gotten nothing in return.

KAMANAKA: I agree.

The Meaning of Pursuing a Single Subject, Documentary Filmmaking by Women

TSUCHIMOTO: All things considered, I’m glad to have worked on Minamata for such a long time.

KAMANAKA: I really wanted to ask you about that. It seems as if it would be hard to keep exploring a single subject for a long time. What do you think?

TSUCHIMOTO: It’s enormously rewarding. It did happen once while I was still absorbed by Minamata disease that I suddenly lost my appetite for it. I thought about how many years I’d spent on Minamata disease: it turned out to be about twenty years. I had to eat, so I thought about other topics and actually worked on

Once you’ve worked on a place like this, you’re able to find any example you might want to illustrate what it is to be human. In Minamata I can find this kind of poverty and that kind of wealth, this sort of resilience and that sort of slyness. For example, there was a case in which a patient died cursing and hateful after immense suffering. And on the other hand there was a patient who recovered from that state and attained enlightenment, gaining as much as had been suffered. There’s quite a range of cases.

KAMANAKA: But I think Minamata is unique. Other parts of

TSUCHIMOTO: Right. But why do you think that is?

KAMANAKA: Is the culture of Minamata different?

TSUCHIMOTO: Basically it’s because they’re living with fish and nature.

KAMANAKA: I agree. When I met Sugimoto Eiko (a Minamata disease patient who appears in director Tsuchimoto’s Shiranui Sea and Minamata Diary), I was surprised

because she spoke of that which “was given.” What was the local term?

TSUCHIMOTO: It’s “nusari.”

KAMANAKA: Yes, “nusari.” Both good and bad are given by the sea. She told me that we have to accept both and live, even though sometimes we get bad things from the sea.

KAMANAKA: When I began making documentaries in the mid-1980s, I didn’t know what kind of documentary film I wanted to make or what kind of subject to pursue. I went to

TSUCHIMOTO: I have some female director friends such as Tokieda Toshie and Haneda Sumiko, and what impresses me about them is how they could handle any kind of project they were given while at Iwanami Film. [5] Because they were workers and couldn’t afford to fool around, they accepted any proposal unless it was really awful. That’s why they don’t have a consistent series of work even though they stayed at Iwanami until they retired. They made some superb films, though. Ms. Tokieda’s three works, I Hate Hospitals, With the Farmers, and Weaving Earth, which explored local medicine in Saku,

KAMANAKA: I heard that Ms. Haneda told Ms. Hamano Sachi (the film director), “Women directors really get going after they turn fifty.” I felt really encouraged.

TSUCHIMOTO: Although I was involved in political movements until I was twenty-eight years old, I never thought that entering the film industry so late was a disadvantage. What I did before then was to my benefit. Nishiyama Masanori, who made Yuntanza Okinawa, also came to me as an assistant director when he was twenty-eight years old. He watched my

The history of film is still so short–you ought to work with the idea that you’re going to be the one to establish what people will later recognize as a history of women directors. Supposing you go on to pursue in different ways the subject that moved you at the start of your career, it’ll be good if the outcome is an interpretation of your work that shows, this is what I’ve spent my life seeking. I want you to leave behind works that show the results of living a life like this.

KAMANAKA: Wow, that’s hard!

TSUCHIMOTO: My films are also a result of my life. Thirty years ago, when I finished my first work Minamata: The Victims and Their World, I thought I had filmed what I should film and was going to stop. When I expressed my relief at finishing, Ishimure Michiko stared me in the face and said “Mr. Tsuchimoto, it’s not going to end with this.” [6] Her words galvanized me. The late Mr. Maeda Katsuhiro (film producer) said to me, “Wouldn’t it be nice if there was one film person who did one thing for a long time?” This was also a hint. I owe so much to Ms. Ishimure and him.

But if I’m to earn my living in film, people around me are not going to encourage me to keep pursuing the same thing. You might be able to continue until you make the third film, but after that you’re going to hear, “Enough already, I get it.” At the same time, I get to feeling that way, too — “Maybe I should do other things.” Of course, I’m interested in other topics, and besides, it’s hard to make money if I work on a single thing. There was even a time when I couldn’t support myself. Surprisingly enough, there’s a wife who’s been willing to let me develop, and that’s why I’ve been able to work so freely, but it’s really difficult.

KAMANAKA: Making films takes all my energy, and I feel lucky to be able to do it. But if I lose money, I won’t be able to move on to the next project.

TSUCHIMOTO: But Hibakusha has the power to make you produce your next work. There’s something that makes me eager to see how you’d make a sequel. That’s because you’re clearly a person with a message.

The Effect of Narration and Subtitles (The Politics of Films without Narration)

TSUCHIMOTO: In your book, you say this about your editing method, “Because the order in which the scenes were shot is the order of my seeing and finding out, I cannot change it.” That was impressive.

KAMANAKA: I was criticized by my first teacher for that. He said that the order should be changed.

TSUCHIMOTO: Depending on how you shoot, you may not be able to change the order.

KAMANAKA: That’s right. Although you can make a film more intelligible by organizing it neatly, I think you lose something, even though it might not show. What it is, and I guess you are also the same, is that the film reflects the feelings and thoughts that I have while I’m shooting, although it may not look like it. The sense that I’m there, that I exist. If I change the chronological order, I feel like that sense is cut off. I don’t want to cut the continuity or the thread that ties me to the scenes I film. This is how I made Hibakusha.

TSUCHIMOTO: Because that’s how you make your films, which is what I expected, the finished product itself isn’t cool.

KAMANAKA: Right, it’s not cool.

TSUCHIMOTO: The American documentary filmmaker Frederick Wiseman was also about thirty-six years old when he began working in film. He had been a lawyer. Now he has about forty titles to his name. I feel an affinity for him. I give him huge credit for the uniqueness of his narrative.

KAMANAKA: His works aren’t narrated. It’s amazing he can make a film without narration.

TSUCHIMOTO: He can do it because he’s who he is. There are many people who say they don’t want to use narration these days. It’s become fashionable, and there’re many films that don’t use narration that you don’t know what to do with when you watch them because they’re immature.

KAMANAKA: I use narration.

TSUCHIMOTO: I do too. I didn’t use it in On the Road (1964) and Prehistory of the Partisan Party (1969), though.

KAMANAKA: I need narration no matter what. I actually think it’s very important to be “easy to understand.”

TSUCHIMOTO: In your case, you have something you’re dying to say, right? It’s not good if the audience doesn’t hear it. That makes complete sense.

KAMANAKA: But as a film style it remains very orthodox. Style is not my priority, but I have this nagging feeling that as cinematic expression the best documentary films are those without narration.

TSUCHIMOTO: I think it’s fine to have scenes without narration, but to try to make that the style for your whole film is to try to be better than the film you just shot. If you and your film have the same foundation, I think it’s fine not to worry about having some scenes where the pictures form the narration and others where you narrate.

KAMANAKA: That I can be free about how I make my films is something that I learned from your films and those by Mr. Ogawa.

TSUCHIMOTO: In my opinion, the reason Wiseman doesn’t have narration is that he wouldn’t be able to make money if he said something radical in the

Narration is central to being “labeled.” That’s why Kamei Fumio put lots of narration in his

KAMANAKA: In Hibakusha, there is little narration in the scenes in the

Structural Issues of the Nuclear Power Industry

TSUCHIMOTO: The home of novelist Minakami Tsutomu is where the nuclear plant is located at

But he gets angry when I try to make a record of it. I brought my daughter, and when she tried to turn on a tape recorder, he noticed and seemed ready to smack her on the head.

One thing he said that I will never forget is that people who do the construction work should be local people. Because local people will do the work carefully.

KAMANAKA: That’s right.

TSUCHIMOTO: Most construction site workers are subcontractors. Usually sub-subcontractors, so their budgets are tight and they want to finish quickly. They’ll do things like mix sand from the ocean, which is full of salt, into the concrete, so no wonder the building doesn’t last.

Whenever it’s reported that inspectors failed to detect a problem in a nuclear plant’s construction, Minakami said, “Of course. Those construction site workers didn’t think they would be living there the rest of their lives, so of course they did a sloppy job.”

From the point of view of the builders, taking “safety” precautions would raise costs too much. Rokkashomura is no exception.

KAMANAKA: That’s right. I went to Rokkashomura again last week, and was finally able to film a study group of people who work at the facility. I heard the stories of people whose work was to go into the casks (special containers for spent nuclear fuel), take the nuclear waste and bring it to the storage pool. They work with great care, and so are convinced they are quite safe, and because their families live in town, they believe nothing bad could happen there and they wouldn’t let anything happen. And they say that the opposition keeps screaming that it’s dangerous, but they haven’t studied the situation adequately. When you hear them talk you almost want to nod your head and say, “Yes, that’s right!” But it doesn’t change the fact that the system itself is fragile.

No one ever talks about the horrible structure of the nuclear power industry whose existence is built on the assumption that there’ll be a certain number of sacrifices and there’s nothing to be done about it. And there’s no sense of this as part of their gut feelings, either.

The industry is structured so that where the villagers work, no matter how rigorous the safety procedures, there’re bound to be accidents and mistakes, but that fact is invisible.

TSUCHIMOTO: It’s just as you say. Another problem with nuclear plants, I think, is that when there’s an accident there are always people who lie about it. And the small lies lead to bigger lies. Everybody who works there has a collective responsibility for those people. There’s always someone whose conscience tells them, “I knew there was something wrong.” It’s clear how the small lies symbolize their overall corruption.

The mayor of Rokkashomura committed suicide in 2002.[8] Nobody can say anything about someone who died. I think we have to keep a close watch on the collective structure of lies in the workplace and the region and the fact that such lies are the source of the greatest devastation.

KAMANAKA: People who lived in Minamata and worked for Chisso but didn’t have symptoms of Minamata disease kept denying the lying that was going on and the accusations by victims against the perpetrators. Why that was so was in large part because Chisso put food on their plates. Things were set up so that if they attacked Chisso, they would put their own lives at risk. It’s the same in Rokkashomura. The money generated by a reprocessing plant is enormous. But the benefits each villager sees is miniscule. Where’s the black hole it’s all being sucked into?

TSUCHIMOTO: Construction, I’d imagine. But you can imagine how little money goes to local workers in the construction industry. Once the construction is complete, the work is done, and you’re unemployed again. So it’s the same situation as in Minamata where you suppress all criticism because you want to keep food on the table.

The local people feel they’re all one family, so even if there’s an injustice, they can’t criticize it.

TSUCHIMOTO: But when there’s an accident, and people from the inside lie during the investigation in order to cover it up, that’s a crime, don’t you think? It’s different from those who work as day laborers. They have an excuse, but for someone who works there regularly, it’s a crime.

KAMANAKA: To begin with, it’s odd that there’s no agency charged with surveillance to ensure against accidents. An investigation of the cause of an accident just becomes an announcement from the “imperial headquarters.” It’s always a report that says, “There was an accident but it didn’t cause any health damage.”

TSUCHIMOTO: I think the study group that you mentioned of people working at the reprocessing plant is a great thing. They aren’t just unthinkingly working to make a living. They’re thinking about whether or not working there is good, and there’s no reason why that couldn’t be taken in a positive direction. If you’re a local resident, you don’t want the land that your grandchildren will live on to be polluted, so if you gain knowledge through study, you might be able to put the brakes on the drive for efficiency. But there’s a “class aspect” even to that kind of study. What kind of knowledge is going to be absorbed? Being sincere about studying isn’t enough; the issue is the truth of the matter. There’s a lot of local pride, so please portray them with utmost care.

Film as “Mirror”

KAMANAKA: On the one hand there are the people who rely on the plant to put food on the table and on the other hand there are the people who oppose it. They live in the same village, but there is no communication between the two sides.

When I went to shoot the transportation of spent nuclear fuel, there were people outsideside the fence shouting, “Stop!” and on the inside those who silently took the material from the casks and brought it in. The protestors want the plant to be shut down because they view an accident as inevitable, and even if there is no accident they see a continuing risk of radiation contamination.

The people who work in the plant say that there is less radiation from the plant than is to be found in nature, and that because they are carrying out their work very carefully there won’t be any accidents.

There’s an enormous gulf between the two sides. I think this is the heart of the matter. And I think that what gets ignored is whether the nuclear power industry can bring real happiness to the people who live in Rokkashomura.

What I am interested in is less the opinions of the protesters than what is going on in the hearts and minds of those who have accepted the plant. What kind of thought process makes it possible for them to say that the plant where they work, which might spread radioactive material, is “good”—and believe it?

TSUCHIMOTO: That’s where, as you make your films, you must hold up the “mirror” that is unique to films. Naturalism won’t do it.

KAMANAKA: Yes, that’s right. A moment ago you said that when you were filming Minamata you set yourself the task of not imitating yourself. I also think that I can’t use the same filming techniques I used in Hibakusha. What I want is for the people who are in my films to suddenly realize, “What we’re doing is …,” as if they were seeing themselves in a mirror, and for those people who think Rokkashomura has nothing to do with them to be startled to find themselves in the film. I show up in that mirror, too.

TSUCHIMOTO: I think you can only find an effective mirror in what comes from that place. There is no way other than to find your mirror in something that exists locally.

KAMANAKA: This period in which I’m filming Rokkashomura is not conducive to providing something that can serve as that kind of mirror. That’s why what I’m getting is more of a diffused reflection.

TSUCHIMOTO: What I mean by a mirror isn’t something that just shows what’s dominant in a given era. I don’t think it’s necessarily bad for the filmmaker to empathize with the opposite side, in other words, the promoters of the plant. To explore why they are so easily duped and carried along.

KAMANAKA: I have a lot of empathy for them. In this day and age, how should we think about what it means to live in and be happy in Rokkashomura? I think we need a different point of view from what we’ve had up to now. But I haven’t found it yet. That’s exactly why I want to understand the real thoughts and lives of the people who support nuclear power. It’s an aspect that hasn’t had a lot of light shined on it, and my work is an attempt to see if they can be understood and empathized with. But when you go back and forth between the promoters of nuclear energy and those opposed, there is a dramatic switch in values, and sometimes it’s terrifying.

TSUCHIMOTO: As you said before, you have to show in a concrete way that if you take another point of view, there’s another structure that becomes visible, and what that is is something you, Kamanaka-san, will have to find.

For me, I would find it in Minamata. Without Minamata, I don’t think I could make a documentary that could stand the test of time, in terms of having an impact on the next generation.

KAMANAKA: Will it be a documentary that can stand the test of time…? But I do think that for my part, I’m doing something challenging. Because it’s not that anything dramatic is happening, just that these are images taken of the everyday life of “ordinary people” who live in the vicinity of a giant nuclear facility. In terms of images it’s extremely hard to turn into a film.

TSUCHIMOTO: There’s a photographer, Higuchi Kenji, who takes pictures of nuclear power plant workers. What’s impressive about him is that he always manages to get on location when there is a regularly scheduled inspection of a nuclear power plant. I’ve tried countless times to do this but never could, so I gave up. But he gets inside. And he takes pictures of workers who are rounded up to do the job.

The people who go forward with plans for a nuclear power plant are bureaucrats who have never done more than glance at a site. They are the kind of people who are completely devoted to “data.” And when plans are handed down as company policy, the same ideology usually prevails at the local offices. Those who have doubts and see that “something is wrong” are down a rung at the site itself. But the people at that level are also positioned to exploit subcontractors and sub-subcontractors. So even though you talk about people working at a plant, there’s a hierarchy. The doubts harbored by such subcontractors never come to the surface, because they’re not used to making such things public. But if there were an accident and they had to take responsibility, I would want to zero in on what goes on in their minds.

The Cheapness of Human Life and Dignity – Refusing to Forget Memories of Inhumanity

KAMANAKA: What I feel when I have gone to both Minamata and Shimokita is the “richness” of Minamata. But I think people who live in Rokkashomura and

I think there must be something in Rokkashomura that is similar to the idea of “nusari” in Minamata, but I haven’t reached it yet. Ms. Sugimoto Eiko, who came up earlier in our conversation, is said to have writhed and cursed until she attained a calm—as if a demon had been washed away. Rokkashomura may still be in the middle of that process.

I very much feel the strength of the love Minamata people have for their land and sea. It bothers me that Shimokita people don’t emanate the same kind of love. Even though I believe it must be there.

Monomizaki Point jutting into the Pacific.

TSUCHIMOTO: Do you think it’s the difference between newer settlers and long-time natives?

KAMANAKA: But the people of Tomari ought to have it. They’ve lived there for many generations, gathering all sorts of seaweed and seasonal fish and cooking them according to their traditions. It’s become their blood and flesh, so they can’t not love their land. How can they accept the existence of a nuclear facility?

TSUCHIMOTO: But at first everyone was against it. There were only a tiny number of “spies” who supported it. And then half of them began supporting it….

KAMANAKA: Now there’s no trace of that. 99% say, “We’ve accepted it.”

Windfarm. The area receives strong winds from both east and west throughout the year. Two companies are using windpower to generate electricity.

TSUCHIMOTO: In Minamata, there was a labor union with thousands of people that in the end was down to about ten. Those ten people stayed in it until they died. It was really fantastic. If you ask why they were able to stick with it, you find it had nothing directly to do with the issue of mercury contamination. It was their memories of inhumanity, of how the company “didn’t treat us like human beings,” that kept them fighting to the end.

KAMANAKA: It’s because it’s

Given that context, I think it’s amazing that Kikukawa Keiko has continued to voice her opposition to the contamination that may occur in Rokkashomura because of the harm it may cause the children of the future. I have great hopes that she may become a mirror for us.

Whenever something happens, I say I want to reach out and hear not only from opponents but also from those who want to coexist with the nuclear plant. People who want to coexist with the plant feel they get unequal treatment because their views are almost never taken up in the media.

TSUCHIMOTO: That’s something we need to fully acknowledge.

KAMANAKA: For instance, the village dry cleaner is in favor of the plant, and he says clearly he made that choice on his own. What he says is part of the truth. There aren’t that many people in the history of Rokkashomura who have gone in front of a camera and said “I’m in favor” and given their reasons for it.

TSUCHIMOTO: What part of Rokkashomura does he live in?

KAMANAKA: In Tomari. Tomari is really fertile. Every time I go there I’m surprised by what I’m given to eat.

TSUCHIMOTO: Tomari has a great fishery. There isn’t a fishing cooperative from Ogawara to Shimokita peninsula that can compete with it. Back when I was going there, the fishing cooperative opposed the plant because they thought that if they couldn’t fish any more they couldn’t support themselves. There’s not much land that could be sold, and if the fishing industry failed, it would be disastrous.

KAMANAKA: But now there are very few people who can make their living from fishing. In all my interviews the fishermen complain that the catch has shrunk, that they can’t catch squid or fish anymore. I wondered if that was really the case, so I did some research. Take for instance sand lances, which are in season now. The catch is now at 17% of its former level. Squid is down to 60% of its former level. It’s been declining since its peak in the 1960s.

The fishermen say the ecological system of the ocean has changed, that it’s the fault of global warming, and that nuclear power can prevent that…

TSUCHIMOTO: Supporters of nuclear energy say that the radiation from a nuclear power plant is no higher than what occurs naturally. But as the late Takagi Jinzaburo (citizen scientist, former head of the Citizens’

KAMANAKA: The reprocessing plant at Rokkashomura is state-of-the-art, and I believe it has the strictest controls in the world.

TSUCHIMOTO: But even there, accidents happen, and they lie about it. The accident at Tokaimura was tragic. It’s unbelievable that they used buckets.

KAMANAKA: Even in the accident at Mihama, there had not been an inspection of the piping in twenty-seven years….[10]

TSUCHIMOTO: Five people died.

KAMANAKA: But it’s impossible to do regular inspections of a plant’s entire piping system, because there are tens of thousands of sections, and just to get to some of them would take thirty minutes. There are many pipes that can only be reached by crawling through areas where radiation exposure must be monitored, and your dosimeter would sound an alarm even before you got there. To do it you would have to use a lot more people. And then you would get more workers who would get radiation poisoning just from performing inspections. But the argument doesn’t go that far. It goes more like, doing that would cost too much money for the industry to survive, and in view of the benefits to society such reforms don’t need to be carried out.

And at that point, human life suddenly becomes cheap. The idea of making ammunition from depleted uranium is also an extension of that careless way of thinking.

When you think about American soldiers, you realize they’re also being dragged off to war zones, made to use depleted uranium munitions, and poisoned by radiation. The soldiers are treated as disposable. Even so, they support the government … It’s the same story in Rokkashomura. They’re forced to believe that it’s the only way they can live….

TSUCHIMOTO: The other day I had a conversation with Kim Dong-won, the director of the South Korean film Repatriation (2003). When I asked why the former North Korean political prisoners who appear in that film resisted recanting for so long, he said that what kept them from doing so didn’t have so much to do with one political regime or the other, but their anger at being insulted and feeling they couldn’t forgive their humiliating treatment. When Kim Dong-won heard that, he thought to himself, “That’s it,” and began making the film. At first he was timid around the former political prisoners. Even though they were released on bail, these were people labeled “Reds” who had come into his neighborhood. And for more than thirty years they didn’t change their beliefs, so he thought at first they must be unmoving, ideological hard-liners. But actually it wasn’t so. Their inhumane treatment and the humiliation they were subjected was repeated each day, so it was impossible for that memory to fade.

KAMANAKA: It wasn’t ideology.

TSUCHIMOTO: It was more like anger against being beaten down as a human being.

The Possibilities of Documentary Film and Screening Activism

KAMANAKA: Documentary film is suited for portraying that kind of thing, I think.

If you try to express the same thing in writing, it necessarily becomes ideological or dramatic. With film, all that appears is a single individual with anger, and if you watch to see why he’s angry you’ll see that it’s an anger that comes from his insides. I think documentary is the better method to portray that.

What I want to portray is whatever is being felt deep down by ordinary, nameless people, whether in Rokkashomura or

With Hibakusha, I said to people. “Please screen it on your own,” and it’s been shown in over 300 venues all across the country through this “viewer-sponsored screening” method. I really like the way you took it upon yourself to go around and show your films on your own, but I don’t think that strategy has come down to this generation very well.

TSUCHIMOTO: We were able to do that because it was Minamata. Because your film achieves a certain standard, it can get around by itself. My Minamata films sometimes had legs of their own, but in areas where it was crucial to show them–remote places–it wasn’t possible for them to get there on their own momentum, so in those places, in other words, on the Shiranui coast (where Minamata disease was first detected), we did a film tour.

And then to show them to indigenous Canadians we had to get a translator to go on a film tour, because the Canadian government itself hated our showing the film. If you show such films to victims, you never know what they’ll start saying, was their thinking. And then for 150 days in the course of two years, we showed the film all over. So you can say I sowed some seeds there, because in

KAMANAKA: Without activist screening becoming a movement, information that should be transmitted won’t be, because it will never be carried on television. Even though there is a flood of information, some information is intentionally hidden.

“What is science?” “Does science really make us happy?” When I make films, I come up against such questions countless times. If you were to ask if scientists ever ask themselves whether what they do really makes people happy, you would have to think the answer would be, probably not. That kind of perspective is missing from the get-go.

TSUCHIMOTO: The Zenkyoto movement (All Campus Joint Struggle Committee) made that an issue, but they couldn’t carry through with it. Students in the Zenkyoto movement sincerely questioned how they could keep their knowledge from becoming entangled in and used by the establishment, and from becoming simply subcontractor

intellectuals for the establishment.

KAMANAKA: By the time I started college, I had absolutely no point of contact with the student movement. Students around me had no interest and only thought about how to make their lives as students more fun. So my student life was one where talking about anything political made people treat you like an idiot.

But I went to

TSUCHIMOTO: How many years were you in the

KAMANAKA: I was in

TSUCHIMOTO: Fundamentally, ideology isn’t something that’s so poisonous …

KAMANAKA: True. It’s thought, isn’t it. But as a filmmaker, when I look at the facts right in front of my eyes, I’m almost never seeing from an ideological standpoint.

TSUCHIMOTO: As for me, that sort of thing was drilled into the marrow of my bones. So when I’m looking for other ways to grasp something, I go about it very consciously. Look, I used to spout a cheap politics when I was part of the student movement. I’ve had some soul-searching to do on that.

KAMANAKA: I spent my life as a student without any ties to a movement, and when I entered the film world and started making documentaries I made works that didn’t incorporate any political or social-movement themes. I bragged that making films was itself a sort of activism for me, but then I started to make films like Hibakusha, and began a movement to ban depleted uranium munitions. After all it’s difficult to separate one’s work from one’s activism.

There are a lot of people who don’t watch my films as pure visual art. So Hibakusha was pretty much ignored by famous critics, although some individuals wrote about it. People have come to think of it as an “activist movie.” But as I’ve screened it in various places, a lot of people from the general audience who say they’ve never seen this kind of documentary before write to tell me their thoughts. And when I read their comments I think to myself, “These people have a better sensibility than the critics” (laughing).

Who to Get Close to, Who to Side With

TSUCHIMOTO: People call me an author who takes sides. It’s a question of whom I’m going to side with, how I’m going to cheer them on. In Chua Swee Lin, Exchange Student (1965), I sided with the exchange student. I portrayed Minamata completely from the victims’ side. I think that’s all right. If you use abstract words and pretend to be fair and don’t do anything, don’t say anything, then you’re clearly siding with the mainstream of that age.

KAMANAKA: And in that sense I think there’s something risky. When you use documentary film as a mode of expression, standing firm on the ground where you want to lend your support—I’m finding that really hard right now as I film Rokkashomura.

TSUCHIMOTO: I don’t necessarily try to make films that are useful for the people I think I should be close to. Because I want to have a future together with these people, if I see something that’s not right in what they’re doing, I think that saying so clearly is also a form of being on “their side.”

KAMANAKA: Oh yes, I think so too.

TSUCHIMOTO: Probably that’s so. Isn’t that okay? If you don’t take sides, you may not be able to see the true shape of things. If you say, “Let’s think about which is more important,” you sink into relativism.

So in all cases, I side with the murdered over the murderer, the harmed over the wrongdoer, the poor over the rich.

KAMANAKA: That’s so, but I feel that such structures themselves have become extremely vague.

TSUCHIMOTO: Isn’t that because whether we’re talking about an individual author or an educator, things are degenerating overall? There’re fewer critics who are pushing people to break new ground for our day and age.

Solidarity in Collaborative Productions

TSUCHIMOTO: Are you going to continue to follow hibakusha in

KAMANAKA: I would like to go to

TSUCHIMOTO: Oh, that’s good.

KAMANAKA: First we’ll collect 500,000 yen, send a video camera and tapes, and ask him to film whatever he likes. When there is a new development, we’ll collect money again to give support. When we get to post-production, then we’ll get support from somewhere—and keep expanding in that way.

I think about how I, as someone whose work is visual, can help

TSUCHIMOTO: My film on

After I finished the English version, I was not sure how to make the Afghan version. Then I thought, why don’t I ask the Afghan director. So I sent him money and asked him to add the subtitles. This is also a collaboration, if you will. It usually costs a lot to film museums such as the Hermitage, but the

KAMANAKA: I also think if citizens in

TSUCHIMOTO: This is something I say in my book, but in this age of images, I’m wondering if it’s a good thing to go filming a foreign country. The people who know the country best are the people who live there. Any country has cameras and broadcasting stations. And there has been a phenomenon we can call “documentary visual imperialism,” where people used their wad of cash to make others obey them, like a certain public broadcaster.

KAMANAKA: I basically agree with you. But there are also cases when a film is allowed to be made because it’s a foreigner doing it. I do think that foreigners enter the country as “others” and can tackle some social problems that local filmmakers can’t. Still, the basic principle should be for people who face the problems to be the agents of expression.

TSUCHIMOTO: That’s how I think, too. It’s a question of how we support their work, both in terms of content and money. I think that’s real solidarity.

Notes:

(Notes added by the translator are set off in brackets and marked “Tr.”)

[1] The Tokaimura Criticality Accident. Japan’s first accident involving a nuclear chain reaction, on Sept. 30, 1999 at the Tokaimura uranium processing plant (fuel conversion plant) operated by JCO Co. Ltd. Three workers were exposed to high levels of radiation, of whom two died from acute radiation exposure. In order to save time, workers preparing fuel for a high-speed experimental reactor didn’t follow proper procedures. They added more than the prescribed amount of uranium to the tank, which resulted in a self-sustaining nuclear fission chain reaction. The criticality continued intermittently for about twenty hours, emitting neutron and gamma radiation. Households within a 350-meter radius of the plant were evacuated, and residents within a one-kilometer radius were asked to stay indoors. Some 700 people, including JCO employees, local residents and firefighters were irradiated.

[2] [The Precautionary Principle often cited by environmentalists addresses just such situations: “When an activity raises threats of harm to human health or the environment, precautionary measures should be taken even if some cause and effect relationships are not fully established scientifically. In this context the proponent of an activity, rather than the public, should bear the burden of proof.” Tr.]

[3] Supreme Court ruling on Minamata. On October 15, 2004, in the first judicial finding of government responsibility for

[4] [The Mutsu-Ogawara Development Project emerged in 1969 as part of the Comprehensive National Development Plan, epitomizing policy emerging from the period of high-growth economics. Under this plan, several regional mega-industrial centers were to be created, all to be linked by high-speed trains and super highways. The Mutsu-Ogawara project, involving an enormous tract of land in

[4] [Ogawa Shinsuke (1935-1992) is another celebrated documentarist best known for his series on the student-farmer Sanrizuka airport struggle. Motivated by the years spent living with the farmers resisting the construction of what is now known as Narita Airport as well as the quelling of the protest, he and his production company eventually moved to a rural area in Yamagata in northern Japan and turned their attention to documenting the details of the agricultural existence while pursuing the history of postwar Japan as reflected in the village. Find a brief introduction here (accessed 1 November 2007). Tr.]

[5] [Iwanami Film Productions was the brainchild of Hokkaido University Professor Nakaya Ukichiro and Kobayashi Isamu of Iwanami Publishers, who wanted to make new kinds of science films. After the company was established in 1950, it attracted such talented members as Hani Susumu, Kuroki Kazuo, Tawara Soichiro (commentator), and a host of photographers, translators, cameramen, and producers, resulting in many prizewinning works. The company filed for bankruptcy in 1998. Its collection was sold to Hitachi Media Productions in 2000. For information on Tokieda Toshie and the atmosphere at Iwanami during its formative years, see this website; for information on Haneda Sumiko, see this website (both accessed 1 November 2007). Tr.]

[6] [Ishimure Michiko is the author of Kugai jodo, arguably the most famous literary work on Minamata. It is now available in English translation by Livia Monnet from the Center for Japanese Studies,

[7] [For two accounts of Kamei (1908-1987), who went to Leningrad for study in 1928, and who, despite the precautions Tsuchimoto refers to here, ended up being jailed for Fighting Soldiers (1939), see here and here, both accessed 1 November 2007. Tr.]

[8] Rokkashomura mayor’s suicide. Rokkashomura Mayor Hashimoto Hisashi committed suicide on May 18, 2002, after he was questioned by the Aomori Prefectural Police in connection with a bribery case relating to public construction in the village. There is great demand for public construction in Rokkashomura, where there is a concentration of nuclear fuel cycle facilities and huge sums invested in construction.

[9] [Tsuchimoto is surely referring to Sellafield, a nuclear site on the Irish Sea in

[10] Mihama Accident. On August 9, 2004, there was an accident at the Mihama No. 3 nuclear power station operated by Kansai Electric Power Corporation (KEPCO) in

Recorded at Cine Associe in Suginami,

This is a slightly abridged translation of a dialogue between Kamanaka Hitomi and Tsuchimoto Noriaki published in Kamanaka Hitomi, Hibakusha: From the Scene of Documentary Filmmaking (Tokyo: Kage Shobo, 2006). Translated by Ann Saphir with the kind permission of the participants and the publisher.

Ann Saphir is a Chicago-based journalist. Norma Field teaches in the Department of East Asian Languages & Civilizations at the

Posted at Focus on December 23, 2007.