Occupation Authorities, the Hatoyama Purge and the Making of Japan’s Postwar Political Order

Juha Saunavaara

The purge of Hatoyama Ichirō and the elevation of Yoshida Shigeru as a substitute prime minister in May 1946 deeply impacted their respective political careers. More important, these actions taken by the Allied occupation authority set the course for postwar Japan’s conservative parties. This article examines the thinking of GHQ leaders that led to these actions. The bureaucratic rule of the so-called Yoshida-school was the long-term side effect of a policy that was meant to guide the development of Japan’s conservative political parties at the dawn of the occupation. The bloodlines of the two statesmen continue to influence contemporary Japanese politics as Hatoyama’s grandson, Yukio, replaces Yoshida Shigeru’s grandson, Asō Tarō, as Japan’s prime minister.

Introduction

Occupation authorities under the command of Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers (SCAP), General Douglas MacArthur, purged a legitimate candidate for the premiership in May 1946 with the purpose of clearing the way for another, more acceptable, conservative. In other words, the occupation authorities not only produced the framework in which party evolution and cabinet building took place, but also shaped the processes and the decisions that emerged. Instead of using formal directives, the occupiers continuously manipulated Japanese politicians through informal but authoritative directives. The occupation authorities’ aims and methods were dynamic and changed over the course of time. However, policy concerning Japan’s conservative parties and politicians adopted during the first months of the occupation was not simply a result of arm-wrestling between American New Deal reformers and those emphasizing the use of Japan as a bulwark against the Soviet Union, but closely followed plans and priorities developed during the war years. The planners’ duties extended from assessing the character of individual Japanese to their postwar role in the production of general roadmaps aimed at creating a democratic Japan. It is thus necessary to examine how wartime planning in the United States’ State, War, and Navy Departments, as well as in the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), influenced SCAP’s decision to purge Hatoyama Ichirō, the leader of the victorious political party of the April 1946 elections, and anoint Yoshida Shigeru.

Several theories exist concerning Hatoyama’s purge on May 4, 1946, just hours before he was to assume the prime ministership and leadership of a single-party cabinet to be built on the socialists’ extra-cabinet cooperation. Most assume that the answer can be found in the activities of the members of either the various General Headquarters (GHQ) sections or the Japanese politicians themselves over the first months of the occupation. These theories introduce different measures taken by these groups and individuals and offer plausible motives for their actions. However, they ignore a significant feature of occupation policy behind GHQ’s decision to purge Hatoyama and seat Yoshida: the preference for prewar non-party-affiliated political actors over party politicians. Related to the interpretations that emphasize the Government Section (GS) New Dealers’ decision to expel Hatoyama is the question of why they eventually accepted another conservative in Yoshida. The answer to these questions lies in the juxtaposition of the concepts of party politics and statesmanship as defined by the both occupation planners and administrators through their criticism of Hatoyama and other party politicians.

Prime Minister Yoshida (left) meeting with Hatoyama Ichirō in October 1952

The Evolution Of An Anti-Party Politician Policy

Interesting studies exist that not only explain the structure and the division of labor between the various occupation planning organizations, but also the topics and contents of the discussions that continued and constantly re-emerged during the multi-year planning process.[1] It is well-known that the participants in these meetings could only agree on a few things concerning the surrender of Japan and its post-defeat treatment. The traditional characterization of the competing views is their division into the so-called ‘China Hands’ and ‘Japan Hands.’

Believing that Republican China would be America’s most important ally in postwar East Asia, the China Hands demanded that the occupation administration force upon Japan extensive political, social, and economic reforms. The influential members of this pro-China, anti-emperor, and anti-zaibatsu group were State Department officials Stanley Hornbeck, Dean Acheson, and John Carter Vincent. George Atcheson Jr., who headed the Office of Political Adviser to the Supreme Commander for Allied Powers (POLAD) that represented the U. S. State Department in Tokyo, is often mentioned as the most visible member of this group at the start of the occupation. Yet there are also claims that despite his background as a China Hand, Atcheson became MacArthur’s trusted ally within a few months of arriving in Tokyo.[2] This group drew many of its ideas from academics and Asia experts like Owen Lattimore, Thomas Bisson, Andrew Roth, and E. Herbert Norman.[3] Occasionally, planners in other U.S. government departments also took firm stands toward Japanese society. Captain H.L. Pence of the Navy Department is often cited as a China Hand because of his propositions calling for the stern treatment of Japan. Wartime opinion polls show that this group’s views reflected those of Americans who wanted to see radical action taken against Japan.[4]

Joseph C. Grew, Eugene Dooman, Robert Fearey, Joseph Ballantine, Cabot Coville, and Earle R. Dickover formed the nucleus of the Japan Hands. These men shared the view that although Japanese society contained some anti-democratic features, Japan could prove to be a loyal U.S. ally should the proponents of democracy be returned to power. Grew, who had served as U. S. Ambassador to Japan prior to the war, and his closest subordinates, advanced a pendulum theory—the 1930s was an exceptional period in the democratic tradition and the pendulum would eventually swing back toward more liberal and cooperative development.[5] They insisted that the emperor was not responsible for Japan’s drive for military conquest. Blame lay instead with Japan’s military extremists and the other ultranationalists who disrupted the country’s earlier modernization progress. The Japan Hands supported a “soft peace” that revived, rather than created anew, Japan’s prewar political and economic institutions.[6]

The Japan Hands also believed that Japanese moderates could help in their country’s reconstruction. It is well-known that as ambassador Grew had developed close ties with people associated with the throne. Grew, together with prewar scholars like Kenneth W. Colegrove, did not hesitate to praise men like Count Makino Nobuaki in prewar and wartime publications.[7] The second group of desirable postwar Japanese leaders were the moderate and pro-Anglo-American officials in Japan’s foreign ministry, including Shidehara Kijūrō, who guided Japan’s internationalist foreign policy in the 1920s. [8] Grew argued that

…in the heat and prejudice of war some will deny that there can be any good elements among the Japanese people. Yet those critics, in all likelihood, will not have known personally and directly those Japanese who were bitterly opposed to war with the United States – men who courageously but futilely gave all that was in them and ran the gravest dangers of imprisonment if not assassination – indeed several were assassinated – in their efforts to stem the tide or, let us say, to halt the tidal wave of insane military megalomania and expansionist ambition.[9]

Grew’s support for the Japanese moderates led some to question his objectivity.[10] Owen Lattimore, for example, denied the existence of Japanese moderates and described the emperor and his henchmen as sacred cows protected by Grew and other so-called Japan experts. In 1945 Lattimore insisted that “we must . . . not be soft with the old-school-kimono “liberals” from Prince Konoe on down, who used to entertain the Embassy crowd so charmingly and made such a good impression on Wall Street, art collectors, and members of the Garden Club.”[11]

Yet it was not only Grew and his colleagues in the foreign office who believed that Japan’s postwar democratic leadership could be drawn from aristocratic Japanese and moderate diplomats. The historian Hugh Borton, who in 1940 authored Japan Since 1931, was also influential in State Department planning organizations and reached similar conclusions in two memorandums. In these documents, written in July and September 1943, Borton mentioned people and groups who could contribute to the establishment of a democratic Japan, including representatives of the emperor’s inner-circle. He also praised Ozaki Yukio, a politician without party affiliation who was often hailed as Japan’s greatest parliamentarian. The only party-affiliated Japanese that he noted positively were former cabinet leaders such as Hamaguchi Yuko and Inukai Tsuyoshi who fell victim to ultra-nationalist assassins of the early1930s. His list included intelligentsia, such as professors from Japan’s imperial universities, younger bureaucrats in the foreign ministry, former foreign service officers, and representatives of the judiciary, as potential moderate leaders for a non-militaristic Japan. To the contrary, he raised doubts over any future political role for Japan’s business leaders.[12] Divisions among wartime planners concerning the so-called Japanese moderates and prewar political parties continued after 1945 and had a significant effect on occupation policy.

Plans for occupied Japan began to take concrete form in early 1944 with general policies created under the auspices of the Postwar Programs Committee (PWC), and with Grew and his former subordinates taking charge of the various planning organizations. The War Department’s Civil Affairs Division (CAD) in Japan also demonstrated increased interest, as seen in the list of concrete questions it sent, together with the Navy Department’s Occupied Areas Section (OAS), to the State Department on February 18, 1944. These questions included inquiry on whether there were any political agencies or political parties with whom the Army could work to restore essential authority in Japan and in its subsequent administration, as well as whether any political parties, organizations or groups should be dissolved.[13]

Answers to these questions began arriving in spring 1944: no political party or agency in wartime Japan was to be preserved in the postwar period. The Imperial Rule Assistance Association (IRAA, Taisei Yokusan Kai) and the Imperial Rule Assistance Political Society (IRAPS, Yokusan Seiji Kai), a parliamentary body established after the 1942 Tōjō-elections, which comprised 98.3 per cent of the House of Representatives, were listed as Japan’s only existing political parties and were to be dissolved. The weakly organized groups in Japan’s House of Peers were judged to be closer to clubs than political parties. The State Department, temporarily under the influence of the Japan Hands, did not create much original policy but continued in many ways in line with Borton, George Blakeslee, and other academics who dominated the planning at its onset. The Japan Hands sought to preserve the emperor and campaigned on behalf of the extra-parliamentary political elite it knew well, but discarded party politics as a source of desirable elements for the reconstruction of Japan.

Pessimism over the conservative political parties and politicians also arose within the OSS. Direct OSS influence in planning remained limited, but its publications conveyed a similar message regarding party politics to the future occupiers, as described in a July 1944 Civil Affairs Handbook:

… Evolution toward a popularly controlled parliamentary government was really blocked not so much by constitutional checks as by fundamental weakness within the political parties and by inhibiting social forces… the two main political parties the Seiyūkai and the Minseitō, were pronouncedly venal, their following drawn by individual leaders rather than principles.[14]

Another set of institutional changes occurred during the war’s final year, after the State-War-Navy Coordinating Committee (SWNCC) was created to coordinate occupation planning. In November 1944, long-time secretary of state, Cordell Hull, retired and was succeeded by Edward R. Stettinius, who appointed Grew as under-secretary of state. On April 12, 1945, Harry S. Truman succeeded the deceased President Franklin D. Roosevelt. In July 1945, James F. Byrnes, an affiliate of the China Hands who advocated a tough occupation in Japan, was chosen to head the State Department. Competition among different interests was severe and new approaches challenged old policy papers. Eventually the final decisions were made inside the War Department, with Assistant Secretary of War John J. McCloy acting as the prime decision-maker. This complex process culminated in three key documents that set the course for the occupation: the Potsdam Declaration, the US Initial Post-Surrender Policy for Japan (also known as SWNCC-150/4), and the Joint Chiefs of Staff’s Basic Directive for Post-Surrender Military Government in Japan Proper (JCS-1380/15). [15] Although these documents reconsidered the basic structure and aims of the occupation, they did not question prior evaluations of Japan’s prewar conservative party politicians and the expectations regarding their postwar activities. The prewar party politicians were not expected to play a significant role in Japan’s postwar recovery.

Nevertheless, the documents that recognized the occupiers’ indirect rule through existing governmental institutions shared the premise that democratic political parties would encourage the democratic advancement of the Japanese people. They advised the removal of all obstacles to democratization. Yet, the limits of party formation were bound by how the ambiguous term “democratic” was to be interpreted. These documents provided no clear definition of what a democratic party was, nor did they identify clearly any potential action models to be employed to reach that end. Finally, they strongly emphasized the need to exclude the elements responsible for Japan’s aggression, which clouded the future of Japan’s conservative politicians.[16] The basic directives, in other words, obligated the occupation authority to set up a political party system but did not determine which Japanese should be allowed to participate in it.

These basic policy papers, together with several other official documents, transmitted Washington’s views to Manila and then to Tokyo headquarters. Although the top positions in GHQ were eventually filled by men close to MacArthur and members of the so-called Bataan Gang, other GHQ members included John K. Emmerson who was in charge of political party reporting during occupation’s first autumn, Charles L. Kades who was the second most influential GS officer, and his close aide Frank Rizzo, who all had experience in Washington planning agencies.[17] An even greater number of GHQ officials came from the offices of the Foreign Economic Administration.[18] State Department representatives in Japan included men who had experienced Tokyo in the mid-1930s. Grew turned down MacArthur’s offer to join the Tokyo Headquarters as a political adviser but actively transmitted his ideas to the general through letters.[19]

Finally, a great number of the division and branch leaders, including Pieter K. Roest who was placed in charge of the unit working with Japanese parties inside the GS, had backgrounds in different Civil Affairs Training Schools and Military Government schools.[20] Thus, they had gained their knowledge of Japan during the war and had been influenced during their training by the opinions of those officials who planned the occupation. This brain drain explains how the occupation authorities’ quickly developed a conception of political currents that worked as a basis for their search of suitable leadership for postwar Japan. Men and women transferred to Tokyo from the United States had already formed assumptions over Japan’s existing political situation and features of the desirable future model prior to their arrival in occupied Japan.

In short, while many felt that the political parties had a place in a democratized Japan, nobody envisioned the old conservative party politicians who had dominated the prewar situation being able to establish themselves as positive political forces in postwar Japan. The Japan Hands had their own answer as to where more appropriate political influences were to be found. Namely, many occupation planners shared the view that a clear distinction should be made between self-seeking party politics and what might be called statesmanship or altruistic work on behalf of the common good. The latter was believed to be characteristic of certain elite Japanese groups who either corresponded in many ways with the planners who had experience in various ministries, diplomatic corps and academic circles, or who had been affiliated with influential planning offices during the prewar period. This distinction that selected the actors who could contribute to the building of a democratic postwar Japan was the most important legacy of the planning process in the actual occupation policy concerning the conservative political parties.

Hatoyama and Yoshida – A Party Politician and a Statesman

The immediate postwar destiny of Hatoyama Ichirō and Yoshida Shigeru had much to do with the fact that although both were conservative and anti-communist, believed in capitalism, and had connections with big businesses, the occupation authorities recognized one of them as a party politician and the other as an old-school statesman. This assessment governed both the occupiers’ early evaluations of Japanese conservatives and their decision-making after the April 10, 1946 Lower House elections.

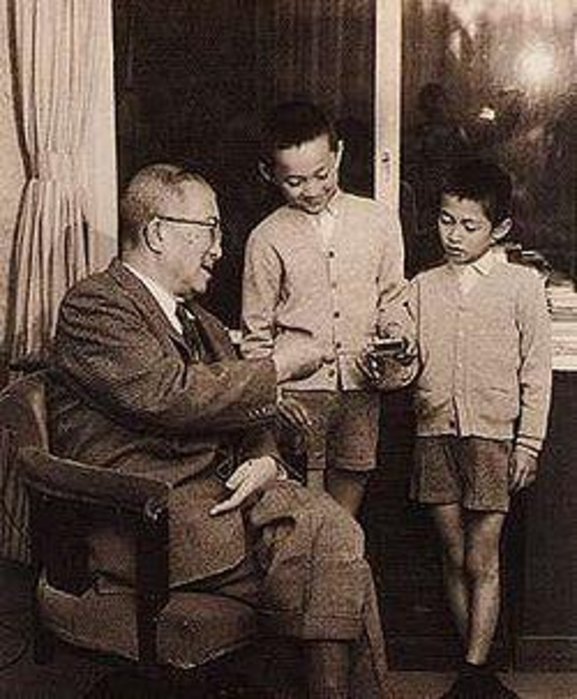

Prime Minister Hatoyama Ichirō with his grandsons Yukio (center) and Kunio (right)

Hatoyama was a party politician with a long career in the prewar Seiyūkai Party. He served as Chief Cabinet Secretary in the Tanaka Giichi cabinet at the end of the 1920s and as Minister of Education in the cabinets of Inukai Tsuyoshi and Saitō Makoto in the early 1930s. As a member of the Seiyūkai he had been an influential leader within the Kuhara Fusanosuke faction. During the war and after the dissolution of political parties, he led the Dōkōkai, a group of Diet members who did not join the Diet Members’ Imperial Assistance League organized in September 1941 under the auspices of the IRAA. According to Ben-Ami Shillony, most of the Dōkōkai’s thirty-seven members were known for their moderate and liberal inclinations.[21] Hatoyama’s name, however, never appeared in occupation planning documents. Even the report by the OSS Research and Analysis Branch issued at the end of September 1945 stated that little was known of his wartime activities. The exception was the commonly reported information that he had resigned from IRAPS in 1943 and continued to serve in the Diet as an independent.[22]

The group that had gathered around Hatoyama during the war quickly initiated efforts to establish a new party immediately after Japan’s defeat. Scholars have emphasized different points in assessing Hatoyama’s actions from his August 11 meeting with his former party comrade Ashida Hitoshi to the November 11, 1945 birth of the Liberal Party of Japan (Nihon Jiyūtō).[23] Yet, it is clear that the selection of Hatoyama to serve as party president, along with his preferred policies, attracted interest among American political observers. Hatoyama made his first visit to occupation headquarters to deliver the party’s platform the day after his nomination.[24]

Those who commented on Hatoyama offered less than glowing praise for the politician. He had been evaluated in October by POLAD’s John K. Emmerson, a former subordinate of Joseph C. Grew in the U.S. Embassy prior to the war. Emmerson identified the Liberal Party strongly in relation to its leader, but did not see in Hatoyama any fresh viewpoint. Emmerson stressed Hatoyama’s personal connection with the militarist Tanaka Giichi cabinet of the late 1920s and criticized his term as minister of education in the early 1930s. He noted Hatoyama’s vigorous anti-communist stance as presented in a speech at the inaugural meeting of the party and in interviews with various GHQ officials. He also described him as a man of unimpressive character with poor English skills.[25] The most interesting evaluation for our purposes, was made by POLAD’s John S. Service, who concluded, “Mr. Hatoyama is not impressive as a person of great conviction, forcefulness or leadership. Although pleasant in personality, he seemed more of a ‘politician’ than a ‘statesman.’”[26]

This description followed an emerging trend which saw occupation officials describe political parties and their leaders in unflattering terms. As with Hatoyama, the criticism most often linked with the conservative parties was their lack of fresh ideas or clear party programs. Parties were seen more as groups that gathered around influential individuals who shared the experience of frustration and were prone to political corruption. Moreover, these descriptions often considered their shared responsibility for the war.[27]

SCAP issued its directives, “Abolition of Certain Political Parties, Associations, Societies, and Other Organizations” (SCAPIN 548) and “Removal and Exclusion of Undesirable Personnel from Public Office” (SCAPIN 550) on January 4, 1946. These directives where translated into Japanese over the following weeks. Such directives had a major impact on conservative political parties. They ended or temporarily suspended the political careers of quite a few members of Hatoyama’s party. Still, the shock caused by the purge was far less than that of their conservative rivals who lost almost all of their incumbent Diet members and acting party leaders. Most importantly, Hatoyama himself was not affected by this particular purge. He continued his vigorous attacks on the communists and led his party in the April 1946 Lower House election. As election day approached, Hatoyama appeared to be the only feasible rival to the incumbent Prime Minister Shidehara Kijūrō.[28]

Yoshida Shigeru, on the other hand, was associated with the Anglo-American moderates. His father-in-law was Count Makino Nobuaki, and he had served as Japanese ambassador to the United Kingdom. He had also developed warm ties with Joseph Grew in the 1930s.[29] Grew praised Yoshida in the ambassador’s Ten Years in Japan as a “pronounced liberal.”[30] Yoshida, however, was not included in Hugh Borton’s early list of potential moderate leaders. Immediately after Japan’s surrender Yoshida’s name did appear on the War Department Military Intelligence Division document titled “Friendly Japanese.” This document, distributed widely internally in September 1945, listed Japanese believed to willing to cooperate with the Allied occupation forces. It described Yoshida as a liberal who favored cooperation with the rest of the world throughout the 1930s. Moreover, the Japanese Army’s resistance to his nomination as foreign minister in 1935-36 worked in his favor.[31] Yoshida was also mentioned in an OSS report dealing with the imprisonment of five prominent Japanese in June 1945. The group had allegedly plotted undercover peace negotiations with the United States and Great Britain.[32] Although this interlude was not mentioned, for example, in “Friendly Japanese,” it later strengthened Yoshida’s image as a representative of anti-war elements and as the leader of a group of like-minded people known to the Japanese police by the code name YOHANSEN, an abbreviation for Yoshida Hansen (Yoshida Anti-War).[33]

Yoshida made his entrance onto the postwar political stage at the suggestion of Prince Konoe Fumimaro, and he in turn promoted Konoe as leader of the movement to establish the Liberal Party. Yoshida replaced Shigemitsu Mamoru as foreign minister on September 17, 1945, and retained this position when Shidehara Kijūrō, another representative of the pre-1931 moderates, became premier after the collapse of the Higashikuni Cabinet on October 5, 1945.[34] By this time State Department officials had already begun to mention Yoshida as a future prime minister.[35] Yoshida’s connection with the Liberal Party, however, remained unclear to political observers.

On the other hand, like more than a few members of the Shidehara Cabinet, Yoshida Shigeru also had ties with major zaibatsu through family or personal relations. He openly sought to protect what he called the “old zaibatsu” and argued on October 19, 1945 that they had done much good for Japan in the prewar period. They also had suffered during the war and thus there was no good reason to do away with them. Instead, he held, it was the “new zaibatsu” created in the 1930s that had cooperated with the militarists and benefited from the war. As occupation authorities had recorded Yoshida’s press statement[36] it is inconceivable that such anti-zaibatsu New Dealers as Charles S. Kades, who disliked Hatoyama, would show any more interest in Yoshida.

POLAD’s role as the leading agency for policy regarding Japanese political parties began to weaken in spring 1946. Prior to then, on December 18, 1945, its leader George Atcheson Jr. authored a memorandum that was in line with the policy practiced at the start of the occupation. Using the same arguments introduced above to criticize Japan’s political parties, Atcheson doubted their capability to produce leaders for postwar Japan any time soon. He was also critical of the group that he called the pre-1931 statesmen. According to Atcheson, this group lacked the flexibility of mind that Japan needed to meet its unprecedented and urgent problems. Still, he recognized that someone had to lead Japan and therefore concluded that Japan’s leaders should be chosen from among those who were the least tainted by the war.[37] As for the pre-1931 statesmen, their inflexibility was a lesser evil than the war responsibility that tarnished party politicians. POLAD’s leader leaned toward the group recommended by the old Japan Hands during the war in determining who to support among Japan’s potential leaders.

Emphasis on the party politicians’ lack of political leadership and the use of prewar history to confirm their unacceptability did not end in spring 1946. The past served as a guide to the probable pattern of Japan’s democracy to the immediate future. Thus the leadership of the democratic movement that would necessarily work through the political parties would be found outside the Diet rather than among the party politicians.[38]

Prime Minister Yoshida Shigeru with his grandchildren in December 1952. (Asō Tarō rear center)

Intervention – Results Without Points From Style

Given the existence of various studies dealing with the political purge program,[39] I will only briefly review the details of the process that led to the purge of Hatoyama on May 4, 1946 and devote more attention to the argument made by Tominomori Eiji, who claims that SCAP treated the bureaucracy softly during the purge, at least when compared to its treatment of conservative party leaders. This leniency allowed former bureaucrats to emerge as the leaders of the conservative parties.[40] If Tominomori is correct, we need to explain why occupation authorities preferred politicians such as Yoshida and Shidehara, whose backgrounds were outside of political party activity, over career politicians with strong party ties.

In the April 10, 1946 Lower House elections the conservative parties emerged victorious as expected, though no single party received a majority. Pre-election evaluations of Hatoyama showed that occupation forces viewed his past political activities in a negative light and, like other acting party heads, he was thought to lack the necessary attributes of sound leadership. Instead, U.S. officials preferred that Shidehara be retained. Shidehara’s prestige, his impeccable character, and the personal confidence that General MacArthur and the emperor allegedly held toward him contributed to this opinion.[41] Claims by Chief Cabinet Secretary Narahashi Wataru further suggest that the occupation authorities supported the incumbent cabinet.[42] The challenge facing occupation officials was how to secure the Japanese leadership they desired while maintaining the impression that the selection process was democratic.

The collapse of the Shidehara Cabinet and the clumsy entrance of Shidehara into the political party world as the president of the Progressive Party of Japan (Nihon Shimpotō) weakened the party’s chances of forming a coalition with the Liberal Party and the Japan Socialist Party (Nihon Shakaitō). This presented the occupation with yet another problem. The obvious choice for prime minister was Hatoyama Ichirō, who was organizing a three-party coalition that required the support of the Socialist Party.

The GS, Public Administration Division interviews with the leaders of the Socialist Party and the Japan Co-operative Party (Nihon Kyōdōtō) revealed that the coalition negotiations had deadlocked over Hatoyama. In an April 19 interview, the socialists’ Katayama Tetsu made it known that he considered Hatoyama unacceptable. There were other conservative politicians with whom his party could cooperate. Four days later Nishio Suehiro suggested to GS’s Harry Emerson Wildes ways to form a coalition cabinet should Hatoyama be purged. Ikawa Tadao, a leader of the Co-operative Party, also let it be known that Hatoyama’s unresolved situation blocked settlement of the cabinet crisis.[43] Thus the GS political observers focused on getting rid of the piece that did not fit. The emergence of familiar and acceptable moderate conservatives such as Matsudaira Tsuneo, the former Imperial Household Minister and ambassador to the United Kingdom and the United States, and Yoshida, under whose leadership the left-center parties were ready to cooperate, most likely increased the occupation authorities’ temptation to intervene in Japan’s domestic politics. The nomination of suitable conservatives that the occupation authorities hoped to see at the helm of the Japanese Government would most likely be deemed acceptable by all but Japan’s left-wing parties.

The Office of the Chief Counter-Intelligence Officer (OCCIO) concluded that the available records did not prove that Hatoyama would fall within the purview of SCAPIN 550. Yet his acceptability as prime minister remained in questioned and some believed that his purge would have a salutary effect on Japanese politics.[44] A twelve-page memorandum issued by the GS on May 3, titled “Report on Hatoyama, Ichiro” depicted Hatoyama as a politician whose education and political experience gave him the potential to make an effective fight for the cause of liberalism in Japan. Unfortunately, it went on, he had failed to accomplish this over his long public career. To the contrary, it claimed, Hatoyama had aided the forces of obscurantism, reaction and militarism throughout his career. The occupation authorities decided to intervene after Shidehara recommended to the emperor that Hatoyama be nominated as prime minister. The occupation authorities even backdated the directive to purge Hatoyama to create the illusion that his purge had preceded his recommendation for the post.[45]

GHQ showed no support for the socialists’ attempts to form a minority cabinet following the purge of Hatoyama, nor did it comment on Shidehara’s decision to withhold recommendation of such a cabinet to the throne. On the other hand, experienced Japanese politicians were certainly capable of reading the situation, as shown by the list of requirements that Hatoyama’s follower was expected to fill. The leaders of the Liberal Party were looking for someone who had close contacts with GHQ, was internationally acceptable, who strongly supported the constitution and was capable of seeing the constitutional issues resolved, and enjoyed congenial relations with the Imperial Court. After attempts to promote Kojima Kazuo and Matsudaira Tsuneo failed, a small group of Liberal Party leaders, led by the purged Hatoyama himself, decided to promote Yoshida Shigeru as party president and Japan’s next prime minister.[46]

Yoshida, well aware of the political situation, sent a letter to General MacArthur on May 15 informing the Supreme Commander of Shidehara’s plan to propose him to the throne as the next prime minister. He asked the general for his opinion on the matter. MacArthur’s response was short and straightforward: he did not oppose the idea and wished Yoshida luck in his bid for the position.[47] Having cleared the way for Yoshida’s premiership, GHQ stepped back so as not to raise suspicions about its already fragile claim that the Japanese themselves had selected the new premier.

The existing interpretations of the purge of Hatoyama Ichirō emphasize either the importance of the power struggle among Japanese politicians or the role of certain GHQ officials. Some doubt that the purge would have been implemented had Shidehara recommended Hatoyama earlier. Similarly, Home Minister Mitsuchi Chūzō’s decision to withhold two documents from GHQ that supported Hatoyama, is alleged to have contributed to the purge. Finally, it has been noted that Narahashi Wataru provided information about the incompleteness of Hatoyama’s pre-election questionnaire to the Civil Information and Education Section together with the communists that facilitated the purge of Hatoyama while supporting a second Shidehara cabinet.[48] Masuda, who offers the most complete argument on the purges, emphasizes the role of the GS left-wing New Dealers in Hatoyama’s purge. Yet others stress the central role played by foreign correspondent Mark Gayn, who mobilized an attack against Hatoyama at the Tokyo Press Club on April 6 by resurrecting some unflattering passages found in Hatoyama’s Sekai no Kao (The Face of the World), which he published in 1938.[49] Having received a translated copy of the book from occupation officials, he distributed parts of it to other foreign correspondents. One of the harshest critics of the occupation authority, Gayn explained his motives as two-fold: As an American he felt that a ranking war criminal was ill fit to serve as prime minister: as a newspaperman he was looking for a front-page story.[50] His reporting certainly embarrassed Hatoyama, but it is perhaps a stretch to trace the Hatoyama purge to the reporter’s efforts.

While all of these theories are worth examining, attention needs to be paid to two critical questions. Why was the occupation leadership willing to follow the guidelines of the GS, and why did the GS New Dealers purge one conservative (Hatoyama) only to accept another (Yoshida)? Only Masuda seems to offer a compelling answer to the first question. He contends that Hatoyama’s over-confidence, typified by his open attack on the communist party that GHQ had legalized, explains why the occupation’s upper echelon sided with the GS. Furthermore, the occupation authorities used Hatoyama’s case as a lesson to the Japanese on GHQ power and the relationship between the victors and the vanquished.[51] Masuda’s first observation is especially important. Open anti-communist statements in democratized Japan most certainly irritated occupation authorities since they opened the door for criticism from the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, it does not seem that Hatoyama’s purge resulted from his own mistakes, that is that the purge grew from seeds that he himself had sowed. Masuda claims that it might have been possible for Hatoyama to advance to the premiership had he adopted a more effective way of dealing with the occupation authority, as Yoshida did. That is to say that his open challenge to, and contradiction of, stated GHQ policy sealed his destiny and forced him to delay his ascent to the office of prime minister until 1954, after the occupation had ended.[52]

Yet, regardless of Hatoyama’s statements or activities, the heart of his purge and Yoshida’s nomination lies in the occupiers’ negative attitude toward the political parties and the dichotomy between party politics and statesmanship outside the Diet. It was not Hatoyama’s eagerly expressed anti-communism that brought about his purge; in fact, the top leadership of the occupation was also anti-communist. Rather, it was his background in prewar party politics that spelled his doom. Regarding Hatoyama’s case, the upper echelon of the occupation authority agreed with the New Dealers, although for different reasons, and found the purge both desirable and eventually necessary. Although the views of these two groups clashed over Yoshida’s appointment, in the end the top leadership carried the day.

The New Deal-wing of the GS did not welcome Yoshida’s premiership, [53] but General MacArthur and his closest conservative aides did. A Civil Intelligence Section memorandum of early May suggested that, “it is most probable that a government headed by Yoshida would be similar in policy and practice to the recent Shidehara cabinet.”[54] This was what the Supreme Command wanted: the continuity of the cooperative and anti-revolutionary policy under the party cabinet supported by the alleged freely expressed will of the Japanese people. The new leadership was expected to ensure social order and thus protect GHQ from external criticism and provide a firm ground for occupation reforms such as constitutional revision. From the very beginning, the occupation authority not only accepted a government led by Shidehara and Yoshida but defended it against communist attacks. On the other hand, it continued to curtail the influence of party politicians.

Hatoyama’s purge had an enormous influence on postwar political history but he was not the only target in May-June 1946. Other prewar party politicians were displaced as well to make room for those who had existed outside the prewar party machines. The purge of Kōno Ichirō, secretary-general of the Liberal Party, and Miki Bukichi, elected speaker of the house and one of the leaders of the Liberal Party, demonstrated that a reputation as a non-recommended candidate in the 1942 election and as an opponent of the rise of military authority was not enough to spare one from the purge. Although not openly specified, their background as party politicians and their connection with Hatoyama Ichirō also made them candidates for purge, as was the case of Liberal Party leader Hayashi Jōji.[55] The only evidence that rendered Kōno unsuitable was an interpretation of a Diet speech that he gave in March 1940 that contained no clearly incriminating statements, but warned of a possible war should the United States government lack wisdom in its China policy. Miki passed the screening for the candidates running in the April election but at the end of May he was purged over evidence that occupation authorities found in the Personal History Files of the General Affairs Section of the Diet Secretariat concerning Miki’s role as adviser (komon) to the Great Japan East Asia Development League. Miki’s denying any knowledge of this alleged appointment was not enough to save him from purge.[56]

Conclusion

The purge of Hatoyama and the embrace of Yoshida manifested the victory of prewar extra-parliamentary statesmanship over what key occupation authorities viewed as corrupt and self-seeking party politics. The situation in June 1946 thus demonstrates the influence of wartime planning on occupation policy over the conservative parties. Occupation planners who harbored diverse preferences concerning the general course of the occupation agreed that the prewar party politicians should not play a major role in the creation of Japan’s postwar democracy. Views of their track record expressed doubt over the possibility of their making any future contribution to this cause. Questions concerning the future of Japanese moderates divided the occupation planners. In the end, the influence of the Japan Hands and Japan experts like Hugh Borton prevailed. The course established by occupation planning was followed faithfully at the beginning of the occupation and the occupation administration successfully selected the new leadership of the political parties and the Japanese government from people suggested by Joseph C. Grew and like-minded analysts. It is therefore not surprising that Grew praised the situation in Japan and the policy adopted by General MacArthur in a his summer message to GS’s Kenneth W. Colegrove, in which he complimented the general for pushing through a successful policy despite ill-conceived directives from a State Department that had been emptied of Japan Hands, the men with the best knowledge and capability to understand Japan’s problems.[58]

GHQ’s policy favoring old-school conservatives like Yoshida and Shidehara, however, had its limitations. Cooperation with statesmen with loose party affiliations worked well for the first one and a half years of the occupation, at a time when the more remarkable reforms like constitutional revision needed to proceed as smoothly as possible. Their enthronement was a result of an undemocratic action made to ensure that they would appear as an acceptable democratically-elected government centered on the political parties. The occupation authorities’ support of the Yoshida Cabinet began to fade as domestic opposition to his party strengthened. Spring 1947 witnessed the birth of a middle-of-the-road regime. Although GHQ sponsored the emergence of the new regime that seemed to promise maintenance of the social order, it lasted less than seventeen months. The cabinets of Katayama Tetsu and Ashida Hitoshi were soon followed by a series of Yoshida cabinets that outlasted the occupation’s tenure in Japan. Yoshida’s last term as prime minister came to an end in November 1954 but his influence did not disappear. In fact, terms like the Yoshida Doctrine and Yoshida School are used to describe the policies of his protégés such as Ikeda Hayato. Hatoyama Ichirō succeeded Yoshida after his purge ended in 1951, finally allowing him to return to politics. The intervention created a juxtaposition that initiated the rivalry between the competing conservative parties in the early 1950s and then, after 1955, within the Liberal Democratic Party.[59]

Juha Saunavaara

University of Oulu, Department of History

Graduate School of Contemporary Asian Studies

[email protected]

Recommended citation: Juha Saunavaara, “Occupation Authorities, the Hatoyama Purge and the Making of Japan’s Postwar Political Order,” The Asia-Pacific Jounal, Vol. 39-2-09, September 28, 2009.

Notes

* I am indebted to Mark Caprio for comments and suggestions on earlier drafts of this paper.

[1] See for example Dale M. Hellegers, We, the Japanese People: World War II and the Origins of the Japanese Constitution, Volume One: Washington, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001; Iokibe Makoto, Nichibei Sensō to Sengo Nihon (The Japan-American War and Postwar Japan), Tokyo: Kōdansha, 2005; Rudolf V. A. Janssens, ‘What Future for Japan?’ U.S. wartime planning for the postwar era, 1942-1945, Atlanta, GA: Rodopi, 1995; Marlene J. Mayo, “American Wartime Planning for Occupied Japan”, in Americans as Proconsuls – United States Military Government in Germany and Japan, 1944-1952, edited by Robert Wolfe, 3-51. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1984.

[2] Howard B. Schonberger, Aftermath of War – Americans and the Remaking of Japan, 1945-1952, Kent, OH: Kent State University Press, 1989, 23, 36. Concerning Atcheson Theodore McNelly, The Origin of Japan’s Democratic Constitution. Lanham: University Press of America, 2000, 36.

[3] Henry Oinas-Kukkonen, Tolerance, Suspicion, and Hostility – Changing U.S. Attitudes toward the Japanese Communist Movement, 1944–1947, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2003, 6.

[4] Iokibe, 2005, 56; Mayo, 1984, 23.

[5] For Grew’s direct references to the swing of the pendulum, see for example Joseph C. Grew, Ten Years in Japan. A Contemporary Record Drawn from the Diaries and Private and Official Papers of Joseph C. Grew United States Ambassador to Japan 1932–1942, Westport, CT: Greenwood Press Publishers, 1973, 32, 338.

[6] Theodore Cohen, Remaking Japan – The American Occupation As New Deal, New York: The Free Press, 1987, 16-18.

[7] Kenneth W. Colegrove, Militarism in Japan, Boston: World Peace Foundation, 1936, 24.

[8] John W. Dower, Empire and Aftermath – Yoshida Shigeru and the Japanese Experience, 1878-1954, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 38, 96, 106-07, 229; Schonberger, 1992, 14-15.

[9] Grew, 1973, xi.

[10] Iokibe, 2005, 78-79.

[11] Owen Lattimore, Solution in Asia, Boston: An Atlantic Monthly Press Book, Little, Brown and Company, 1945, 190. See also pages 29, 46.

[12] Documents T-358 and T-381 introduced before for example by Janssens. Janssens, 1995, 124-27.

[13] For earlier analysis of these questions see Hellegers, 2001, 160-65; Janssens, 1995, 152.

[14] OSS, R&A(#1319,2A), Army Service Force Manual (M354-2A), Civil Affairs Handbook. Japan, Section 2: Government and Administration, July 1944, 1-2. The Occupation of Japan – U.S. Planning Documents 1942-1945. Published by Congressional Information Service and Maruzen, (OJUSPD), 3-B-4. See also Army Service Force Manual (M354-2A), January, 1945, 63-66. OJUSPD 3-B-3.

[15] More on these developments in Takemae Eiji, The Allied Occupation of Japan, translated and adapted from the Japanese by Robert Ricketts and Sebastian Swann, New York: the Continuum International Publishing Group, 2002, 210, 217; Iokibe, 2005, 108-13, 146, Janssens, 1995, 257, 265-71.

[16] These basic documents can be found for example in Occupation of Japan: Policy and Progress, The Department of State, Far Eastern Series 17. s.l.s.a., 53-55, 73-81; Joint Chief of Staff, Basic Directive for Post-Surrender Military Government in Japan Proper (JCS-1380/15), November 3, 1945 . NDL, GHQ/SCAP Records, Government Section, GS(B)00291.

[17] For more about the background of these men, see Justin Williams, Sr., Japan’s Political Revolution under MacArthur – A Participant’s Account, Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1979, 35-36, 61.

[18] Dean Acheson, Present at the Creation – My Years in the State Department, New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 1987, 46-47; Dale M. Hellegers, We, the Japanese People: World War II and the Origins of the Japanese Constitution, Volume Two: Tokyo, Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2001, 580-81, 632, 645.

[19] Grew’s letters transmitted his ideas concerning both prewar and postwar Japan. Grew even sent MacArthur a copy of his book where he praised his Japanese affiliates. Grew memorandum of Conversation, 16 July 1945. OJUSPD 5-E-33. Concerning the correspondence between Grew and MacArthur: Grew memorandum of Conversation, July 16, 1945. OJUSPD 5-E-33; Grew to MacArthur, August 22, 1945. NDL, MacArthur Memorial Archives (MMA) MMA-14 (RG 10) Personal Correspondence VIP File, Reel 2, Box 5, Folder 7 Joseph C. Grew; Letter from Grew to MacArthur, 3 October 1945. MMA-14 (RG 10) Personal Correspondence VIP File, Reel 2, Box 5, Folder 7 Joseph C. Grew.

[20] See for example Williams, 1979, xiv, 52-63, 69.

[21] Ben-Ami Shillony, Politics and Culture in Wartime Japan, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981, 19-20.

[22] OSS, R&A, (#3263) report, September 28, 1945, 3-4. OJUSPD 3-C-31.

[23] For more on the formation of the Liberal Party, see Masumi Junnosuke, Postwar Politics in Japan, 1945 – 1955, Translated by Lonny E. Carlile, Berkeley, CA: Institute of East Asian Studies, University of California, Berkeley Center for Japanese Studies, 1985, 78-80; Shinobu Seizaburō, Sengo Nihon Seijishi, 1945-1952, Volume I (Postwar Japan Political History, 1945-1952, Volume I), Tokyo: Keisō Shobō, 1965, 201; Tominomori Eiji, Sengo Hoshutōshi (A History of Postwar Conservative Parties), Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2006, 1-3.

[24] Hatoyama Ichirō, Hatoyama Ichirō – Kaoru Nikki (The Diary of Hatoyama Ichirō – Kaoru), Tokyo: Jōkan Hatoyama Ichirō hen – Chūō Kōron Shinsha, 1999, 412.

[25] John K. Emmerson, POLAD, Political Parties in Japan, October 11, 1945. NDL, GS(A)02522; John K. Emmerson, POLAD, Weekly report, November 12, 1945. NDL, GS(A)02521.

[26] John S. Service, POLAD, Memorandum of conversation, November 25, 1945, 3. The United States National Archives, College Park, Maryland (NARA), RG 84, Box 11, Folder 18.

[27] John K. Emmerson, POLAD, Political Parties in Japan, October 11, 1945, 1-2. NDL, GS(A)02522.

[28] While the other names were lacking, the two leading candidates were compared. For example POLAD’s William J. Sebald did not hide his preference of Shidehara. William J. Sebald, POLAD, Weekly report, April 9, 1946. CUSSDCF Reel 1 windows 659-62.

[29] Dower, 1979, 108-09, 217-18, 229.

[30] Grew, 1973, 178.

[31] P. E. Peabody, War Department, Military Intelligence Division, Washington, for the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, (August 1945). NDL, Legal Section (LS)24079-LS24084.

[32] OSS, R&A Branch Division. Intelligence Reports, Alleged Japanese Peace Plot of June 1945. NARA, RG 226, Box 262, XL 17358.

[33] Detailed introduction of YOHANSEN activities, see Dower, 1979, 227-72.

[34] See Masumi, 1985, 42-43; Ashida Hitoshi, Ashida Hitoshi Nikki, volume 1 (The Diary of Ashida Hitoshi, volume I), Tokyo: Ikanami Shoten Kankō, 1986, 213.

[35] Department of State, Interim Research and Intelligence Service, R&A Branch, R&A 3449. Biographical Notes on the Japanese Shidehara Cabinet Appointed in October 1945. November 9, 1945. O.S.S/State Department Intelligence and Research Reports, Part II, Postwar Japan, Korea and Southeast Asia (OSS/SDIRR), Reel 2, Document 15; Department of State, Office of Intelligence Collection and Dissemination, Division of Biographic Intelligence, R&A 3767. June 14, 1946. Biographic Reports o the Members of the Yoshida Cabinet Appointed in May 1946. OSS/SDIRR, Reel 3, document 6.

[36] The Acting Political Adviser in Japan (Atcheson) to the Secretary of State, October 24, 1945. Foreign Relations of United States. Diplomatic Papers (FRUS) 1945, vol. 6, 780-781; Robert A. Fearey, POLAD, Review of Developments in Japan August 26 – November 20, 1945. Confidential U.S. State Department Central Files. Japan Internal Affairs 1945 – 1949, A microfilm project of University Publication of America, 1985. (CUSSDCF), reel 1 windows 324, 331.

[37] George Atcheson Jr., POLAD, Memorandum for the Supreme Commander, December 18, 1945, 3-4. GS(A)02521.

[38] See for example: POLAD, Sebald, Political Parties in Japan, March 12, 1946, 1-3. NARA, RG 226, Box 445, XL 46249; Civil Intelligence Section, SCAP, Occupational Trends Japan and Korea. Report No. 15, 5, March 27, 1946. NARA, RG 331, SCAP, Natural Resources Section, Library Division, Publications, 1945-51. Entry 1828, Box 9091.

[39] Various studies deal with the political purge program. Among them the most profound reading is offered by Masuda Hiroshi whose detailed interpretation of the causes and effects of the individual purge cases is based on exceptionally rich source material. Another classic study is written by Hans H. Baerwald, a former purge officer who shows how the purge served as an instrument for the democratization of Japan. Masuda Hiroshi, Seijika Tsuihō (The Purge of Politicians), Tokyo: Chuōkōron Shinsha. 2001, passim; Hans H. Baerwald, The Purge of Japanese Leaders under the Occupation, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1959, passim; Mayumi Itoh, The Hatoyama Dynasty. Japanese Political Leadership Through the Generations, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2003, 84-102.

[40] Tominomori, 2006, 20-22.

[41] William J. Sebald, POLAD, Weekly report, April 9, 1946. CUSSDCF Reel 1 windows 659-62.

[42] Narahashi Wataru, Gekiryū ni Sao Sashite – Wa ga Kokuhaku (Boating in a Swift Current – My Confessions), Tokyo: Yokushoin, 1968, 133-134; See also Masumi, 1985, 98-99.

[43] P. K. Roest, GHQ, SCAP, GS, Public Administration Division, PPB, Memorandum to the Chief of Section, April 19, 1946, 3-4. NARA, RG 331, Box 2142, Folder 2; P. K. Roest, GHQ, SCAP, GS, Public Administration Division, PPB, Memorandum to the Chief, GS, April 23, 1946. NARA, RG, 331, Box 2142, Folder 2; P. K. Roest, GHQ, SCAP, GS, Public Administration Division, PPB, Memorandum to the Chief, GS, April 26, 1946, 1. NARA, RG 331, Box 2142, Folder 2.

[44] This and the following documents were introduced by Masuda. Masuda, 2001, 43-57. Originals can be found from NDL, GS(B)03013 and GS/B)00905-00910 or NARA, RG 331 box 2275B and box 2134.

[45] Masuda, 2001, 57-58.

[46] Kōno Ichirō, Kōno Ichirō Jiden (The Autobiography of Kōno Ichirō), Tokyo: Denki Kankō Iinkai, Tokukan Kōkai, 1965, 187-89, 191-93.

[47] Yoshida Shigeru to General Douglas MacArthur, General of the Army, May 15, 1946. NDL, MMA-14, Reel 6, Yoshida Shigeru 1946.

[48] Mayumi Itoh introduces various readings concerning the purge of Hatoyama, Itoh, 2003, 84-102; Masuda, 2001, 42.

[49] Ibidem.

[50] Mark Gayn, Japan Diary, Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle Company, 1981, 159-64, 176.

Gayn’s source may have been in the Civil Information and Education section because archival sources reveal that CI&E’s Lieutenant Colonel Donald R. Nugent sent a confidential report to the OCCIO three days before the Press Club incident. Report contained excerpts from Sekai no Kao and Nugent’s conclusion according to which it should be studied whether Hatoyama was to be purged under the provisions of Category G of SCAPIN 550 and the Jiyūtō be dissolved under the terms of the statement issued by SCAP on February 18, 1946. Donald R. Nugent, C, CI&E to OCCIO, April 3, 1946. NDL, Hans H. Baerwald Papers, BAE-122.

[51] Masuda, 2001, 33-34, 59-60.

[52] Masuda, 2001, 60-61.

[53] See for example Kataoka Tetsuya, “The 1955 System: The origin of Japan’s Postwar Politics”, in Creating Single-Party Democracy – Japan’s Postwar Political System, edited by Kataoka Tetsuya, 151-168. Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press, 1992, 158; Masuda, 2001, 22, 42, 61.

[54] Civil Intelligence Section, SCAP, Occupational Trends Japan and Korea. Report No. 20, 1-4, May 1, 1946. NARA, RG 331, SCAP, Natural Resources Section, Library Division, Publications, 1945-51. Entry 1828, Box 9091.

[55] Headquarters, 81st Military Government Company, Kochi, Shikoku, APO 24, Captain Korb, Memorandum, March 22, 1946. NDL, GS(B)03008; PAD, Note to Commander Swope, May 28, 1946. NDL, GS(B)03008. In the end, Hayashi managed to escape purge at this time.

[56] G-2 to Government Section, June 18, 1946. NDL, GS(B)03182; CW, GS to G-2/CIS, June 21, 1946. NDL, GS(B)03182; General Headquarters, United States Army Forces, Pacific, Check Sheet, from G-2 to GS, June 1, 1946. NDL, GS(B)03332; GHQ, SCAP, GS, Memorandum for Record, June 5, 1946. NDL, GS(B)03332; General Headquarters, SCAP, Check Sheet, from GS to C of S, June 6, 1946. NDL, GS(B)03332.

[57] Wildes, GHQ, SCAP, GS, Public Affairs Division, PPB, Liberal Party, June 20, 1946, 8-9, 11-12. NDL, MMA-03 (RG 5), Reel 82.

[58] Grew to Colegrove, July 6, 1946. NDL, MMA-14 (RG 10) Personal Correspondence VIP File, Reel 2, Box 5, Folder 7 Joseph C. Grew.

[59] Kataoka, 1992, 11-15.