Making the Invisible Empire Visible

Film Review by John Junkerman

Mention “The Insular Empire” to the average American, and they’d likely have no idea what you were talking about. They probably still wouldn’t get it if you gave them another clue: “America in the Mariana Islands.” These are the title and subtitle of a new film by Vanessa Warheit, which began screening on PBS earlier this year.

It is the singular misfortune of the residents of Guam and the Northern Marianas to have been born on tiny islands of great strategic value in the mid-Pacific Ocean. The consequence has been their colonial subordination for four centuries to a succession of empires: Spain, the United States, Germany, Japan, and, since the Pacific War, the US again.

A “colony” of the American “empire”? Of course, the US does not acknowledge that the “territory” of Guam and the “commonwealth” of the Northern Mariana Islands are colonies. But, as the film points out, the residents of these islands bear American passports yet have only token representation in the US Congress. They have the ‘right’ to fight in the US military (soldiers from Guam have died in Iraq and Afghanistan at a per capita rate four times as high as any US state), but they don’t have a vote in the election of the commander-in-chief. One third of Guam is controlled by the US military and the island is slated for a massive military buildup, but as a “non-self-governing territory,” the islanders have no say in the matter.

The principle of government with the consent of the governed, over which the American colonies fought the War of Independence, does not apply to the Mariana Islands. Yes, these are colonies.

It is one of the ironies of the American “empire of bases” (in Chalmer Johnson’s apt phrase) that the empire remains largely invisible to all but the soldiers who occupy these bases spread across the globe and the citizens of the lands that host them. What is true of the de facto American empire is even more true of these colonies: to Americans, they are no more than tiny specks in the ocean, 6,000 miles from the coast of California. This film, the first comprehensive telling of the story of the Marianas to the American public, performs the invaluable service of making this invisible empire visible.

The film could not be more timely. The transfer of 8,000 Marines (and nearly 10,000 dependents and civilians) to Guam from the Futenma air base on the equally militarized Japanese island of Okinawa is scheduled to take place in 2014. Preparations for the $12 billion base construction project (which will include extensive dredging of coral reef so the naval base can accommodate aircraft carriers, among numerous other expansions) are already underway. The project will bring in some 79,000 people, including temporary construction workers, boosting the population of the already crowded island by 40 percent. While welcomed by some sectors on Guam as an economic transfusion, the buildup threatens to destroy the island’s natural beauty and cause an environmental disaster. The US Environmental Protection Agency in February blasted the military’s draft environmental impact statement as “environmentally unsatisfactory,” citing expected shortages of drinking water, the over-burdening of the island’s crumbling sewage treatment infrastructure, and inadequate plans to mitigate ecological damage.

But the military’s presence and proposed expansion are not the focus of this film, only in part because the military refused to allow the filmmakers access to the bases and declined requests for interviews. Rather, the film aims to illuminate the history that has left these islands pawns in America’s global chess game. It is a complex history: despite being part of the same archipelago, Guam (an American colony since the Spanish-American War in 1898), and the Northern Marianas (which include the islands of Saipan and Tinian) have different colonial pasts and distinct political status today. This history is deftly told with inventive graphics and superbly researched archival footage, reflecting the eight painstaking years spent in producing the film.

The islands’ complex history is matched by a deeply conflicted identity. Much of the population is intensely loyal to the US, reflecting the pervasive presence of the military and the high levels of enlistment, yet the islanders are perpetual second-class citizens. English is spoken and the dominant culture is American (the world’s largest K-Mart is on Guam), yet there are persistent efforts to preserve the indigenous Chamorro language and culture. Guam’s economy is heavily dependent on tourism and the military, but a different course of development might have been chosen if the islanders had control of their land and destiny (choices that the Guam Buildup will put forever out of reach).

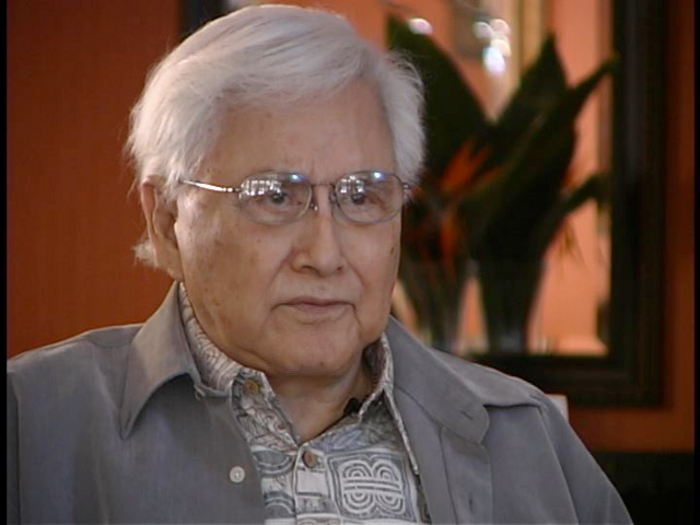

Warheit has provided depth and character to these issues of identity by following four individuals, two each from Guam and the Northern Marianas, through the course of the film. The eldest, Carlos Taitano, a former speaker of the Guam Legislature, was born in 1917 and thus witnessed and participated in Guam’s postwar history, during which “the people of the Marianas were a distant afterthought,” he observes. A businessman (the island’s Coca-Cola bottler) and an advocate of statehood, he died in 2009, before the film was released, his distant dream unrealized.

|

Carlos Taitano |

When Hope Cristobal represented Guam in the Miss Universe pageant in 1967, she visited the States for the first time and encountered anti-Vietnam War protests in San Francisco, opening her eyes to a counter-military narrative she had never imagined on Guam. She has since become an advocate for Guam’s self-determination and the director of a museum of Chamorro culture. It is, in many ways, a reclamation project: when she was a schoolgirl, she was punished for speaking the Chamorro language (recalling the forced Americanization of Native Americans, and the parallel Japanization of the Okinawa islanders), and few young people now speak the language.

|

Hope Cristobal |

Where Guam was occupied by the US Navy and Air Force, Saipan (in the Northern Marianas) was used by the CIA as a secret base to train Chinese and Southeast Asian insurgents, and Lino Olopai found work on the base as a security guard. Pete Tenorio worked as a caddy on the CIA’s golf course. The Northern Marianas were then a UN trust territory under US administration, until 1975, when a plebiscite approved a “covenant” that made the islands an American commonwealth.

Lino Olopai and Pete Tenorio appear in an excerpt of the film.

Tenorio entered politics and eventually was elected “resident representative” of the commonwealth, with an office in Washington, DC, where he negotiates not with Congress but with the Department of the Interior’s Office of Insular Affairs. “People here [in the US] are just not aware of this relationship,” he says in frustration, “and if they’re not aware, what’s our solution to it?” Olopai pressed for independence at the time of the plebiscite and when the commonwealth status was approved, he left Saipan for the Caroline Islands to reconnect with his roots. There he learned the dying art of celestial navigation, which he has continued to teach to others since his return to Saipan.

While the US military is not the focus of the film, its presence is inescapable. US soldiers march in uniform in Guam’s annual Liberation Day parade, commemorating the defeat of the Japanese occupation of the island on July 21, 1944. More than 60 years later, the military is still lionized as Guam’s “liberator,” but, as Hope Cristobal comments, “The US has not given us anything but the military.” If the Guam Buildup goes forward as planned, there will be precious little room left on Guam for anything but the military.

For many years, Cristobal made an annual trek to the UN, to appeal for Guam’s self-determination before the Special Committee on Decolonization. In one of the most poignant moments of the film, her daughter Hope Cristobal, Jr. follows in her footsteps and testifies at the UN. The road ahead for Guam is a long one, she comments, “but even if you make one ripple in this big ocean, it still counts.”

The compact (59-minute) and information-packed format of the film make it a valuable resource for teaching and organizing. For information on PBS broadcasts and other screenings of the film, consult the blog here. The film is available on DVD, and a Japanese-subtitled version will be available soon, through the same blog address. The film’s website is here.

John Junkerman wrote this review for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

See also, LisaLinda Natividad and Gwyn Kirk, Fortress Guam: Resistance to US Military Mega-Buildup

John Junkerman is an American documentary filmmaker and Japan Focus associate living in Tokyo. His most recent film, “Japan’s Peace Constitution” (2005), won the Kinema Jumpo and Japan PEN Club best documentary awards. It is available in North America from First Run Icarus Films. He co-produced and edited “Outside the Great Wall,” a film on Chinese writers and artists in exile that will be released in Japan and abroad later this year.

Recommended citation: John Junkerman, “Making the Invisible Empire Visible,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 20-1-10, May 17, 2010.