The Nuclear Age at 64: Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the Struggle to End Nuclear Proliferation

1. Hiroshima Mayor’s Statement

PEACE DECLARATION

That weapon of human extinction, the atomic bomb, was dropped on the people of Hiroshima sixty-four years ago. Yet the hibakusha’s suffering, a hell no words can convey, continues. Radiation absorbed 64 years earlier continues to eat at their bodies, and memories of 64 years ago flash back as if they had happened yesterday.

Fortunately, the grave implications of the hibakusha experience are granted legal support. A good example of this support is the courageous court decision humbly accepting the fact that the effects of radiation on the human body have yet to be fully elucidated. The Japanese national government should make its assistance measures fully appropriate to the situations of the aging hibakusha, including those exposed in “black rain areas” and those living overseas. Then, tearing down the walls between its ministries and agencies, it should lead the world as standard-bearer for the movement to abolish nuclear weapons by 2020 to actualize the fervent desire of hibakusha that “No one else should ever suffer as we did.”

In April this year, US President Obama speaking in Prague said, “…as the only nuclear power to have used a nuclear weapon, the United States has a moral responsibility to act.” And “…take concrete steps towards a world without nuclear weapons.” Nuclear weapons abolition is the will not only of the hibakusha but also of the vast majority of people and nations on this planet. The fact that President Obama is listening to those voices has solidified our conviction that “the only role for nuclear weapons is to be abolished.”

In response, we support President Obama and have a moral responsibility to act to abolish nuclear weapons. To emphasize this point, we refer to ourselves, the great global majority, as the “Obamajority,” and we call on the rest of the world to join forces with us to eliminate all nuclear weapons by 2020. The essence of this idea is embodied in the Japanese Constitution, which is ever more highly esteemed around the world.

Now, with more than 3,000 member cities worldwide, Mayors for Peace has given concrete substance to our “2020 Vision” through the Hiroshima-Nagasaki Protocol, and we are doing everything in our power to promote its adoption at the NPT Review Conference next year. Once the Protocol is adopted, our scenario calls for an immediate halt to all efforts to acquire or deploy nuclear weapons by all countries, including the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, which has so recently conducted defiant nuclear tests; visits by leaders of nuclear-weapon states and suspect states to the A-bombed cities; early convening of a UN Special Session devoted to Disarmament; an immediate start to negotiations with the goal of concluding a nuclear weapons convention by 2015; and finally, to eliminate all nuclear weapons by 2020. We will adopt a more detailed plan at the Mayors for Peace General Conference that begins tomorrow in Nagasaki.

The year 2020 is important because we wish to enter a world without nuclear weapons with as many hibakusha as possible. Furthermore, if our generation fails to eliminate nuclear weapons, we will have failed to fulfill our minimum responsibility to those that follow.

Global Zero, the International Commission on Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament and others of influence throughout the world have initiated positive programs that seek the abolition of nuclear weapons. We sincerely hope that they will all join the circle of those pressing for 2020.

As seen in the anti-personnel landmine ban, liberation from poverty through the Grameen Bank, the prevention of global warming and other such movements, global democracy that respects the majority will of the world and solves problems through the power of the people has truly begun to grow. To nurture this growth and go on to solve other major problems, we must create a mechanism by which the voices of the people can be delivered directly into the UN. One idea would be to create a “Lower House” of the United Nations made up of 100 cities that have suffered major tragedies due to war and other disasters, plus another 100 cities with large populations, totaling 200 cities. The current UN General Assembly would then become the “Upper House.”

On the occasion of the Peace Memorial Ceremony commemorating the 64th anniversary of the atomic bombing, we offer our solemn, heartfelt condolence to the souls of the A-bomb victims, and, together with the city of Nagasaki and the majority of Earth’s people and nations, we pledge to strive with all our strength for a world free from nuclear weapons.

We have the power. We have the responsibility. And we are the Obamajority. Together, we can abolish nuclear weapons. Yes, we can.

August 6, 2009

Akiba Tadatoshi

Mayor

The City of Hiroshima

2. Nagasaki Mayor’s Statement

2009 Nagasaki Peace Declaration

We, as human beings, now have two paths before us.

While one can lead us to “a world without nuclear weapons,” the other will carry us toward annihilation, bringing us to suffer once again the destruction experienced in Hiroshima and Nagasaki 64 years ago.

Doves fly in Nagasaki on August 9, 2009 at 11:02 a.m.

This April, in Prague, the Czech Republic, U.S. President Barack Obama clearly stated that the United States of America will seek a world without nuclear weapons. The President described concrete steps, such as the resumption of negotiations on a new Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty (START) with the Russians, pursuit of the U.S. ratification of the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT), which bans all nuclear explosions in the air, the sea, underground and in outer space, and seeking to conclude a treaty to ban the production of highly enriched uranium and plutonium, both essential components of nuclear weapons. The President demonstrated strong determination by saying that “as the only nuclear power to have used a nuclear weapon, the United States has a moral responsibility to act,” which profoundly moved people in Nagasaki, a city that has suffered the horror of atomic bombing.

President Obama’s speech was a watershed event, in that the U.S., a superpower possessing nuclear weapons, finally took a step towards the elimination of nuclear armaments.

Nevertheless, this May, North Korea conducted its second nuclear test, in violation of the United Nations Security Council resolution. As long as the world continues to rely on nuclear deterrence and nuclear weapons continue to exist, the possibility always exists that dangerous nations, like North Korea, and terrorists will emerge. International society must absolutely make North Korea destroy its nuclear arsenal, and the five nuclear-weapon states must also reduce their nuclear weapons. In addition to the U.S. and Russia, the U.K., France and China must sincerely fulfill their responsibility to reduce nuclear arms under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT).

In a bid for thorough elimination of nuclear armaments, we urge the strongest efforts towards the Nuclear Weapons Convention (NWC), which the U.N. Secretary General Ban Ki-moon last year called on governments to negotiate actively. It is necessary to insist that not only India, Pakistan and North Korea, but also Israel, a nation widely believed to possess nuclear weapons, and Iran, a nation suspected of nuclear development, should participate in the convention in order to ensure that those nations totally eliminate their nuclear weapons.

Supporting the speech delivered in Prague, the Government of Japan, a nation that has experienced nuclear devastation, must play a leading role in international society. Moreover, the government must globally disseminate the ideals of peace and renunciation of war prescribed in the Japanese Constitution. The government must also embark on measures to establish a firm position on the Three Non-Nuclear Principles by enacting them into law, and to create a Northeast Asian Nuclear Weapon-Free Zone, incorporating North Korea.

We strongly urge U.S. President Obama, Russia’s President Medvedev, U.K. Prime Minister Brown, France’s President Sarkozy and China’s President Hu Jintao, as well as India’s Prime Minister Singh, Pakistan’s President Zardari, North Korea’s General Secretary Kim Jong-il, Israel’s Prime Minister Netanyahu and Iran’s President Ahmadinejad, and all the other world’s leaders, as follows.

Visit Nagasaki, a city that suffered nuclear destruction.

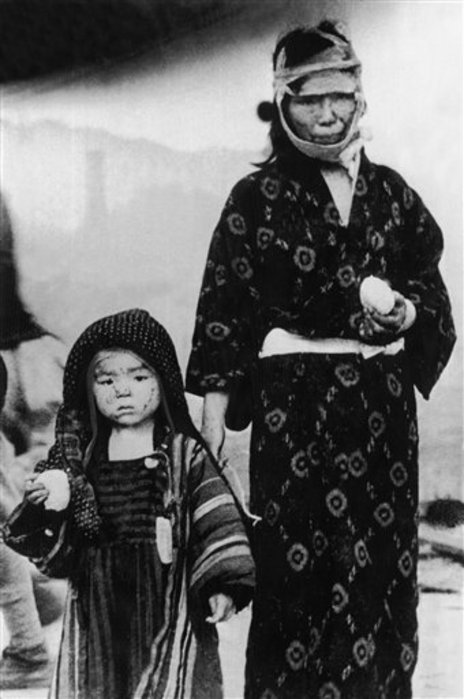

Visit the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum and stand at the site of nuclear devastation, where the bones of numerous victims are still interred. On August 9, 1945 at 11:02 a.m., Nagasaki was devastated by intense radiation, heat rays of several thousand degrees Centigrade and horrific blast winds. Fierce fires destroyed Nagasaki, turning the city into a silent ruin. While 74,000 dead victims screamed silently, 75,000 injured people moaned. Everybody who visits is sure to be overwhelmed with the anguish of those who died in this atomic bombing.

You will see those who managed to survive the atomic bombing. You will hear the voices of elderly victims, who try to tell the story of their experiences even as they continue to suffer from the after-effects. You will be stimulated by the passion of young people, who carry out their activities in the belief that although they did not share the experience of the atomic bombing, they can share the awareness that strives for the elimination of nuclear armaments.

Now, in Nagasaki, the General Conference of Mayors for Peace is being held. In February next year, the Nagasaki Global Citizens’ Assembly for the Elimination of Nuclear Weapons will be held, attended by NGOs from both within Japan and overseas. For the next year’s NPT Review Conference, citizens, NGOs and cities strive to strengthen their unity.

People in Nagasaki are circulating petitions calling for President Obama to visit Nagasaki, a city that experienced atomic bombing. Each of us plays a vital role in creating history. We must never leave this responsibility only to leaders or governments.

We ask the people of the world, now, in each place, in each of your lives, to initiate efforts to declare support for the Prague speech and take steps together towards “a world without nuclear weapons.”

Some 64 years have passed since the atomic bombing. The remaining survivors are growing old. We call once again for the Japanese government, from the perspective of the provision of relief for atomic bomb survivors, to hasten to offer them support that corresponds with their reality.

We pray from our hearts for the repose of the souls of those who died in the atomic bombing, and pledge our commitment to the elimination of nuclear armaments.

Taue Tomihisa

Mayor of Nagasaki

August 9, 2009

3. UN Secretary General Brockmann’s Statement

The gruesome reality of atomic destruction has lost none of its power to inspire grief and terror—and righteous anger . . . toward the elimination of nuclear weapons.

Remarks by H.E. Miguel D’Escoto Brockmann, Pesident of the United Nations General Assembly at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Ceremony, August 6, 2009

Dear brothers and sisters,

1. I am honoured, and deeply moved, to be with you on this most solemn occasion, in which we remember one of the greatest atrocities the world has ever witnessed.

2. I am here today as President of the General Assembly of our United Nations, but also in my personal capacity.

3. As a Roman Catholic priest, and a disciple of Jesus of Nazareth, I want also, from the depth of my heart, to seek forgiveness from all my brothers and sisters in Japan for the fact that the captain of the fateful B-29 Enola Gay, Paul Tibbets, now deceased, was a member of my Church. I am consoled, to a certain degree, that Father George Zablecka, the catholic chaplain of the mission, recognized, after the event, that this was one of the worst imaginable betrayals of the teachings of Jesus. In the name of my church, I ask your forgiveness.

4. Sixty-four years later, the gruesome reality of atomic destruction has lost none of its power to inspire grief and terror — and righteous anger.

5. We cannot, have not, and will not succeed in eliminating the danger of nuclear weapons being used again, unless and until we have eliminated nuclear weapons from the face of the earth and until we have placed the capacity for making those weapons under reliable and lasting international control.

6. I understand that this is a tall order, full of technical and political complexities. Yet, if we are to keep faith with the victims and survivors of the first nuclear terror, we must resolve, here and now, to take convincing action to begin working toward the explicit goal of complete nuclear disarmament.

7. Taking into account that Japan is the only country in the world that has experienced the atrocity of nuclear bombardment, and that furthermore, Japan has given the world a magnificent example of forgiveness and reconciliation, I believe that Japan is the country with the most moral authority to convene the nuclear powers to this emblematic City of Peace, holy Hiroshima, and begin in earnest the process to lead our world back to sanity by starting the way to Zero Tolerance of nuclear weapons in the world.

Thank you.

Rev. Miguel d’Escoto Brockmann, born in Los Angeles, is a Nicaraguan diplomat, politician and Catholic priest.

4. Under a Cloud: Lessons and legacies of the atomic bombings

Jeff Kingston

Jeff Kingston revisits the epochal events of August 1945 in Hiroshima and Nagasaki and draws on interviews in Japan, India and Pakistan to assess their ongoing political and social fallout.

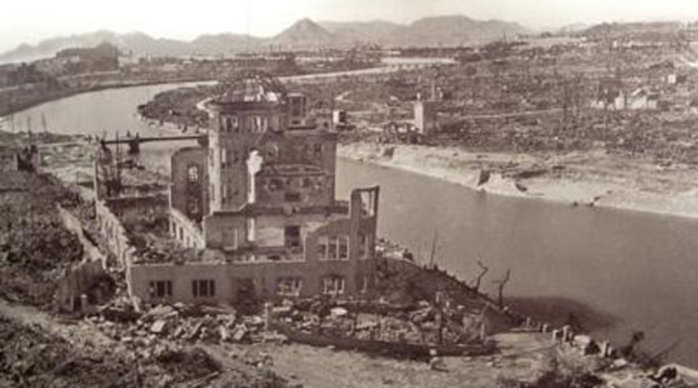

Ground Zero, Hiroshima, August 6, 1945.

Global fashion icon Issey Miyake recently made headlines by divulging in a New York Times article he penned on July 13 that he is a hibakusha, a survivor of the atomic bombings of Japan.

Grassy knoll: The Atomic Bomb Memorial Mound in Hiroshima holds the ashes of 70,000 unidentified victims of the bomb.

Only 7 when he witnessed the incineration of his hometown of Hiroshima at 8:15 a.m. on Monday, Aug. 6, 1945, he recalled: “I still see things no one should ever experience: a bright red light, the black cloud soon after, people running in every direction trying desperately to escape — I remember it all. Within three years, my mother died from radiation exposure.”

Miyake had remained quiet all these years, not wanting to be defined by his past or to become known as the “hibakusha designer.” But he was inspired to speak out after an April 5 speech by U.S. President Barack Obama in Prague, in which he announced his intention to work toward abolishing nuclear weapons, declaring, ” . . . as a nuclear power, as the only nuclear power to have used a nuclear weapon, the United States has a moral responsibility to act.”

Miyake explained that he wants to support this process by reminding people of the nightmare he hopes nobody else ever endures. Like other hibakusha, he also hopes that during Obama’s first official visit to Japan, tentatively scheduled for November, the president will go to Hiroshima to jump-start his avowed quest for nuclear disarmament by viscerally reminding everyone of what is at stake.

On last Thursday’s 64th anniversary of the first atomic-bombing, Hiroshima Mayor Akiba Tadatoshi lent his support, saying that most people in the world want the elimination of nuclear weapons. He declared: “We are the Obamajority. Together we can eliminate nuclear weapons. Yes we can.”

To this day, though, expert opinion remains divided between those who think the atomic bombs saved lives and caused the quick Japanese surrender that followed on Aug. 15, 1945, and those who challenge those claims and provide alternative explanations of why U.S. President Harry S. Truman used the bombs.

Nonetheless, since 1945 both the Japanese and U.S. governments have pushed the controversy off to the side in their shared focus on harmonious bilateral relations. For the Japanese government, too — relying as they do on the U.S. nuclear umbrella — the atomic bombings are an especially delicate issue.

Former Defense Minister Kyuma Fumio had to resign in 2007 after igniting a public outcry by suggesting that the U.S. decision “could not be helped.”

And just this week, Tamogami Toshio, the former Air Self-Defense Force chief ousted over his apologist views concerning Japan’s militarist past, sparked a furor and reopened wounds in his speech, “Casting Doubt on the Peace of Hiroshima,” delivered there on Aug. 6. He said, “As the only country to have experienced nuclear bombs, we should go nuclear to make sure we don’t suffer a third time.”

Across the once-war-torn Pacific, however, raising awareness in the United States about the devastation has been a dilemma because highlighting the suffering endured by the Japanese is sometimes perceived as a way of deflecting attention away from the torment Japan inflicted throughout the region.

Indeed, in 1995 the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. fueled controversy by planning an exhibition to present, and challenge, the case for Truman’s decision to drop two atomic bombs on two Japanese cities. However, intense political pressures forced the axing from the exhibition of the revisionist critique of Truman’s decision.

In the wider world, meanwhile, ongoing nuclear weapons proliferation suggests that the lessons of Hiroshima and Nagasaki are not as appreciated as they should be.

It is against this background that The Japan Times invited a writer from Pakistan and one from India to discuss the implications of proliferation, along with two Japanese academics asked to share their thoughts about the legacy of the atomic bombs.

Jeff Kingston is Director of Asian Studies at Temple University Japan Campus in Tokyo and an Asia-Pacific Journal associate.

This five-part series of articles appeared in The Japan Times on August 9, 2009.

5. A-bombings ‘were war crimes’. ‘Mass killing of civilians by indiscriminate bombing’ condemned by International Peoples’ Tribunal

An interview with Yuki Tanaka

Guilty.

Mother and child, Nagasaki Aug 9, 1945. Yamahata Yosuke

Sixty-two years after the first atomic weapon was tested in New Mexico, international jurors issued a verdict on the atomic bombings, finding U.S. leaders guilty of war crimes and crimes against humanity.

Judgment Of The International Peoples’ Tribunal on the Dropping of Atomic Bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki (July 16, 2007)

” . . . the Tribunal finds that the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki violated the principles prohibiting the mass murder of civilians, wanton destruction of cities and villages resulting in excessive death not justified by military necessity. Therefore, these acts constitute War Crimes . . . ” The following is the text of an interview with Yuki Tanaka , research professor at the Hiroshima Peace Institute, editor of “Bombing Civilians” (2009) and an organizer of the tribunal.

Why did you decide to organize the tribunal?

I wanted to place Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the wider history of bombing civilians. They are the worst cases, but we want to establish the principle that mass killing of civilians by indiscriminate bombing is criminal, anywhere.

Yuki Tanaka, an organizer of the International Peoples’ Tribunal. Hasegawa Jun

Also, the atomic bombings were not dealt with at the Tokyo Tribunal (the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, 1946-48). The Allies did not want to be accused of war crimes involving the bombing of civilians because they had engaged in so much of it in Europe as well as Japan.

I worked to establish a tribunal in order to raise the issue of the criminality of the atomic bombings to counter the U.S. argument that they were necessary to end the war.

It is important to focus on the criminality of the acts regardless of the strategic or tactical reasons.

What impact do you hope to have?

When I talk to groups in the United States, they say the atomic bombings were necessary to end the war.

I reply that if I have a sick child requiring expensive medicine I can’t afford, and then I rob and kill a neighbor to get the money and buy the drug and save my child’s life, the murder is still a crime even if it was to save my child. So a good reason for committing a crime does not justify a criminal act.

Killing 70,000 to 80,000 people in one second . . . isn’t this a massacre and crime that clearly violates international law? No matter the reason, a crime is a crime.

The U.S. needs to admit its wrongdoing and apologize for the same reason Japan needs to apologize to the Chinese. It is important to educate people in the U.S. that killing large numbers of civilians is a crime not to be repeated, but it has been continuously repeated in Korea, Vietnam and the Middle East. This is not a problem of the past, it is still a problem in the present. This is educational for Japanese too, because if you want Americans to admit and atone for their crimes, Japan also must do so.

What is your goal?

Our main goal is reconciliation with the U.S. In order to reconcile, the U.S. must first recognize that it committed crimes and apologize. Otherwise there can be no reconciliation. The hibakusha (atomic- bomb survivors) want an apology, and for them this is a necessary condition for reconciliation. If the U.S. did so it would improve the relationship tremendously.

In Prague, U.S. President Barack Obama (in a speech on April 5) became the first president to accept some responsibility for the atomic bombings, saying that the U.S. must accept moral responsibility by abolishing nuclear weapons. This took many Japanese by surprise, but there is still the matter of legal responsibility. Once the criminality of atomic weapons is established it will be easier to abolish them.

So at the government level there already is reconciliation, but not among the victims. The hibakusha are not reconciled, and are still waiting for an apology. Even after they die, the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the descendants of hibakusha will still demand justice and keep the issue alive, just as in Nanjing the Chinese have sustained their campaign for justice. It won’t fade away. The past continues to haunt the present.

A woman prays in Nagasaki’s Urakami Cathedral on Aug 9, 2009.

The U.S. has sought refuge in the concept of collateral damage to justify civilian casualties. It makes it seem that such deaths are an inevitable and unavoidable cost, an inadvertent consequence — whereas they are the main target. Bombings of civilians has been accepted to some extent as normal in war. It is a crime.

People here hope that Obama will visit Hiroshima later this year and make a clear apology and accept legal responsibility, not only moral responsibility, but that is unlikely.

The entire verdict of The International Peoples’ Tribunal can be accessed here.

6. ‘It is time to discuss this more frankly’

Kazuhiko Togo, Professor of International Politics at Kyoto Sangyo University, is a former Ambassador to the Netherlands and the author of 2005’s “Japan’s Foreign Policy 1945-2003” and 2008’s “Rekishi to Gaiko” (“History and Diplomacy”). He is also a grandson of Shigenori Togo (1882-1950), who, after serving as Ambassador to Germany and then to the Soviet Union, was appointed Foreign Minister from 1941-42 and again from April to August 1945. After the war, he was sentenced to 20 years’ imprisonment for war crimes, and died in prison.

What do you think are the critical issues concerning the atomic bombs in contemporary Japan?

Ambassador Togo’s written response is as follows: Surprisingly, there has been little serious debate in Japan about the Hiroshima-Nagasaki atomic bombs (of Aug. 6 and Aug. 9, 1945) in the context of Japan-U.S. relations. Conservative opinion leaders tended to look at the issue in the context of the U.S. nuclear umbrella, while liberal opinion leaders tended to look at this issue as an object of universal evil that requires global abandonment. But Defense Minister Fumio Kyuma’s statement in June 2007 that “the dropping of atomic bombs could not be helped” provoked anger among Japanese people, and his ensuing resignation shows that something is changing.

The government has no intention to politicize this issue with the U.S. government, and I concur that clearly this is a wise policy. But at the level of academics and opinion leaders, the time has come to discuss the issue more frankly. Here are four points that in my view come to the mind of many Japanese:

First, are the Americans truly aware about the nature of atrocities committed? People who were subjected to the bomb are still suffering from physical pain, and they are literally dying because of the radioactive aftereffects. The apocalyptic description of the massacre is shocking enough, but how many Americans are aware that the bombs continue to have such a lingering fatal impact? Japanese victims of the bombs in general have accepted the postwar settlement and are suing only the Japanese government requesting more adequate compensation. But does this postwar settlement justify U.S. disinterest in this unprecedented human suffering caused by the U.S. during World War II?

Second, in accordance with the existing norms of international law and the simple logic of fairness and human rights today, how can one justify the killing of Japanese women, children and elderly people for the sheer sake of protecting the life of American soldiers, whose destiny was to fight and die for their country? It is axiomatic to say that indiscriminate bombing of noncombatants and cities was a common practice during World War II, including by Japan. But does this “relativization” justify the catastrophic level of atrocities inflicted on Japanese civilians by the atomic bombs?

Third, were the atomic bombs really necessary to end the war? Efforts made by American scholars to question this point are commendable.

Two key questions remain. First, from April 1945 the Japanese government was engaged in serious efforts to end the war. Their efforts culminated in the dispatch of a formal instruction to the Japanese Ambassador in Moscow on July 13 that the Emperor wanted to terminate the war, and asking (Soviet premier Joseph) Stalin to receive his special envoy (former Prime Minister Fumimaro) Konoe to negotiate the terms of surrender. Stalin and (U.S. President Harry S.) Truman agreed on July 18 at Potsdam (in Germany) to remain evasive in responding to the Japanese request. Stalin was determined to attack Japan before it capitulated. But why did Truman stay evasive?

The second key question concerns the final order to drop two bombs in early August that was issued on July 25 by (U.S. Secretary of War Henry L.) Stimson and (U.S. Secretary of State George) Marshall, with, no doubt, Truman’s approval although a written record was not found, and the Potsdam Declaration was issued on July 26. The key clause that might have facilitated a Japanese surrender, i.e., preservation of the Imperial household, was not included in the Potsdam Declaration despite experts’ recommendation. It gives an impression that Truman reserved sufficient time for the two bombs to be dropped before Japan’s capitulation. Is this perception correct, and if so, why did he do so?

Distant echoes: The Korean Cenotaph in the Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima, which commemorates some 70,000 Koreans killed or irradiated by the atomic bombings.

Fourth, are the Americans aware that it is not the conservatives who are now most vocal in condemning the dropping of the two bombs as violating international law, but rather that it is the best of Japanese liberals who have condemned the U.S. actions as crimes against humanity? Saburo Ienaga (a prominent historian), who sued the Japanese government for 30 years for not allowing more detailed descriptions in school textbooks of atrocities committed by Japanese soldiers, made it clear that “the three major atrocities committed during World War II are Auschwitz, Unit 731 (the Imperial Japanese Army’s germ-warfare unit) and Hiroshima.” Another example is (Hiroshima Peace Institute professor) Yuki Tanaka, known as a strong advocate of comfort women’s rights, who helped organize an international people’s tribunal in 2006 that found U.S. leaders guilty of war crimes for dropping the atomic bombs.

It is difficult for me to propose some definite solution on this controversial, political and emotional issue. In general, I support the proposal by veteran journalist Fumio Matsuo for a reciprocal wreath presentation by the U.S. president at Hiroshima and the Japanese prime minister at the (USS) Arizona Memorial in Pearl Harbor as an initial gesture of reconciliation. But more important may be the expansion of exchanges among citizens’ groups for the sheer purpose of improving mutual understanding during this initial stage of reconsidering this historical memory.

8. Many in India hail its nukes

Pankaj Mishra is an Indian writer and frequent contributor to the New York Review of Books. His most recent books are “An End to Suffering: The Buddha in the World” (2004) and “Temptations of the West: How to be Modern in India, Pakistan and Beyond” (2006).

In remembrance: The Memorial Cenotaph in the Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima. Built in 1952, the arch shape — through which the A-bomb Dome is visible — was chosen to represent a shelter for the souls of the atomic bomb’s estimated toll of 140,000 victims, including those who died from radiation illnesses. Beneath the arch, a cenotaph bears the names of those who perished.

In India, have lessons been learned from the atomic bombings of Japan in 1945?

I wish I could say yes, but that is not the case.

Let’s go back to the 1945 war-crimes tribunal in Tokyo (the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, 1946-48). There, (Indian) Justice Radhabinod Pal, who was once well known in India but is now all but forgotten, argued that the Allied powers were also guilty of war crimes, citing the atomic bombings. This alienated his fellow judges at the tribunal, but as a result he became famous and respected in Japan.

In the late 1940s, Indian opinion severely judged the atomic bombings, but since then public opinion has shifted dramatically — especially since India’s first nuclear-weapon test in 1974. At that time there was not much domestic public reaction, but in 1998 when India tested nuclear warheads there were massive celebrations across the country and the Indian middle class was ecstatic. The capacity to blow up the world was seen as a great advance and marked India’s arrival, at least in the minds of the people, as a great superpower.

It is depressing that the lessons of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have not been learned. The atomic bomb is just seen as a bigger, more powerful and more destructive bomb, and there is no appreciation for the devastating consequences and radioactive fallout. This is why officials and pundits can speak blithely about nuclear exchanges.

Pal’s views about atomic bombings as war crimes are completely forgotten.

Writer Pankaj Mishra, who questions India’s “nation rising” euphoria and the superpower status many there feel its nuclear weapons bestow. Nina Subin

The media has not been helpful, and rather is part of the problem because it has been jingoistic and nationalistic regarding nuclear weapons. India is in the grip of a “nation rising” euphoria and sees nuclear weapons contributing to the glory and international prominence of India, putting it on an imaginary par with the United States, Russia and China as a great superpower. Nuclear weapons are emblematic of national pride and widely supported by the public out of their ignorance about what they can do and what would happen if India launched one.

Were the atomic bombings war crimes?

In the early post-World War II era, yes, they were overwhelmingly seen as war crimes. Today, among those who know about the atomic bombings, virtually everyone would condemn them as war crimes. But most Indians are simply not aware of this history.

Is there support in India for nuclear disarmament?

There is a consensus that using nuclear weapons is a bad idea because the neighbor can retaliate. However, there is also a consensus that having nuclear weapons is a good idea. Back in 1998, the ruling Congress party opposed the tests, but it has since changed its stance, and all parties now support having nuclear weapons.

Antinuclear activists were discouraged under the Bush administration (U.S. President George W. Bush (2001-09) and by the deal made with India on nuclear programs. This deal reflected the influence of the India-American lobby that has a similar clout on India-related issues as the Jewish lobby has on Israeli matters. The Bush administration deal symbolized India’s rise as the central ally of the U.S. in Asia as a counterweight to China. This fantasy of India as a great superpower appeals to them because a deal with the U.S. means “Big Daddy” endorses India.

(U.S. President Barack) Obama has abandoned this Cold War thinking, and that is raising anxieties in the Indian government. But antinuclear activists are heartened by Obama’s comments about disarmament and the revival of the antinuclear movement in the U.S.

9. ‘No public discourse’ in Pakistan about its nukes

Kamila Shamsie is a Pakistan-born novelist who was educated in the United States and now lives in London, from where she recently gave the interview below. In her 2009 novel “Burnt Shadows,” Shamsie explores the indelible mark that the larger sweep of history leaves on people caught up in its maelstroms. It is an ambitious epic delving into personal sufferings against the backdrop of tragic histories spanning six decades, three generations and five countries.

Novelist Kamila Shamsie, whose latest book addresses how unimaginable horrors easily become possible in war. Mark Pringle

The book opens in Nagasaki in 1945, where the protagonist, a young Japanese woman named Hiroko Tanaka, falls in love only to lose her German fiance, Konrad Weiss, in the atomic bombing. Trying on her mother’s summer kimono she steps out to the veranda just as the flash and blast incinerates the city, burning the garment’s beautiful swan design onto her back.

Nagasaki, August 9, 1945 in the aftermath of the bomb

This hibakusha (atomic bomb survivor) later travels to New Delhi to visit the family that might have become her in-laws, ends up marrying a Muslim man working for them, and is then caught up in the 1947 Partition of British India (between present-day India, Pakistan and Bangladesh) — eventually settling in Pakistan.

Following miscarriages brought on by exposure to radiation, which afflicted many hibakusha, she gives birth to a son. However, the lives of Hiroko’s and Konrad’s families continue intersecting with devastating consequences — an allegory for what happens in a world run by whites in their self-interest, despite any fitful good intentions they might have.

This is a novel that accuses, but also tries to convey the personal consequences of war, racism and geopolitics. Shamsie connects the dots, showing how powerfully the past shapes the present — and shadows the future. Hiroko comes to a rueful awakening, lamenting, “I understand for the first time how nations can applaud when their governments drop a second nuclear bomb.”

Her book makes us think about how unimaginable horrors easily become possible in war.

What inspired this novel?

The story idea came from the 1998 nuclear tests by India and Pakistan, and then when they were at the brink of war in 2002. I wanted to write a story set in Asia with the shadow of nuclear weapons in the background. It was to be about a Pakistani man and a Japanese woman, and that led me to Nagasaki — with the India-Pakistan confrontation a murmur looming behind.

I wasn’t able to visit Nagasaki due to difficulties securing a visa, all the documents they wanted and the need for a sponsor. And I knew that even if I went I could not see prewar Nagasaki. The city itself is not the focus of my book as much as what people can decide to do to others in the context of war.

When I was researching about the atomic bombs I was reading (U.S. Pulitzer Prize-winning author and journalist) John Hersey (1914-93) about Hiroshima, and he mentioned the presence of Germans there. So then I had my character for Konrad, the fiance.

Nagasaki is the most cosmopolitan and Christian city in Japan, with a long history of exchanges and contacts with the outside world. Thus it is ironic that of all cities it was one to suffer this fate.

My grandmother was half-German and living in Delhi during World War II. It was difficult for her as a German to live in British India at that time. So she became the inspiration for Konrad’s sister, even though her life was very different. And once Hiroko left Nagasaki after the bomb and visited Konrad’s relatives in India it was natural that she was caught up in the Partition, which brought her together with a Pakistani man and took her to Pakistan — my center of gravity.

The arc of the story continues to touch on the encounter between different parts of the world, one that was transformed, especially for Pakistan, by 9/11. And so her son is also caught up in these tragedies of history that become tragic personal histories.

I once attended a lecture and the speaker drew our attention to Nagasaki, asking how it was possible to make that decision to drop the second bomb even after the consequences of the first were known.

Before Hiroshima, it may have been possible to imagine the horror, but it was not known. But (U.S. President Harry S.) Truman knew about Hiroshima, knew what it had done to the people — and yet did not stop the second bomb. This to me is truly horrific. To make that decision to repeat the atomic bombing speaks to the pathologies of war. There is nothing you won’t do or justify in the context of war. That single moment, that single weapon, killing tens of thousands of people in an instant.

Do the atomic bombings shape public discourse in Pakistan?

The lessons of Hiroshima and Nagasaki have had too little impact on public discourse in India and Pakistan. In the few days between the 1998 nuclear tests by India and those subsequently conducted by Pakistan, hibakusha visited Pakistan and begged the government not to proceed. A Pakistani filmmaker made a documentary with riveting and horrible images of what happened in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and tried to get viewers to imagine what Pakistan’s cities would look like if nuclear weapons were used.

I, too, am trying to bring forward into the present the echoes of this past.

But in Pakistan it is all about India. “They have them so we need them” is the mentality. So there really is no public discourse about the implications of nuclear weapons. In the school curriculum nothing is taught about the consequences of nuclear weapons, and there is no raising of awareness about the effects of radiation.

At the time of the tests in 1998, the state controlled the media so there was no questioning or examining the government’s decision. In the English- language media there has been some critical opinion voiced, but there is a consensus supporting the decision to test because India has nuclear weapons. They are viewed as a deterrent and a guarantee that the rest of the world will step in to prevent a war because so much is at stake.

In Pakistan, nuclear weapons are looked on as just a bigger bomb, and in an abstract way people accept the need for it without thinking through the logic of fallout affecting people in both countries. (Abdul Qadeer) Khan is despised by Pakistan’s liberal intellgentsia, but seen as a hero by the general public because without his efforts (to develop atomic weapons) they believe Pakistan would be at India’s mercy.

Did international sanctions after Pakistan’s nuclear tests have much impact?

Sanctions by Japan were not as important as those imposed by the United States. Pakistan is really dependent on the U.S., and the impact was huge, sending the economy into a nosedive. Pakistan was on the verge of bankruptcy. Then 9/11 rescued Pakistan’s economy because suddenly it was needed for its geostrategic usefulness.

But the sanctions did not cause people to wonder about whether the nuclear tests were a good idea. Instead they made them feel unfairly persecuted, and made people aware how dependent and vulnerable Pakistan’s economy is.

What message are you trying to convey through your writing of five novels to date?

As a novelist, I try to avoid saying there is a single message in my books, because it is about what readers bring to the reading and see in the novel. In “Burnt Shadows,” I write about the threat of what nations can do to each other in the name of self-interest and defense.

Do you think the atomic bombings were war crimes?

It is hard to figure out what part of war is not a crime. It’s all criminal. War is the absence of morality, what we can get away with. Everyone in war commits war crimes.

I wish the myth of Truman as a great president was challenged. How could he be great when he made the decision to use atomic weapons?

But I don’t believe that other nations are any different from the U.S. The difference is that the U.S. was in a position to use them and it did. It is the imperial power of this era, and thus it is more involved in war and the inevitable crimes that entails. But it is too easy to blame the U.S. — nations and people need to look at themselves and their actions and choices.

Can you imagine a nuclear war might happen?

Yes. India and Pakistan were so close to war in 2002. Once you engage in war — and you have this weapon — there is the possibility of using it. The gap between conventional and nuclear war is not as great as people believe. If you are desperate and losing a war, there is no certainty it would not be used with horrific consequences for everyone.

Recommended citation: Akiba Tadatoshi, Taue Tomihisa, Miguel d’Escoto Brockmann, Jeff Kingston, “The Nuclear Age at 64: Hiroshima, Nagasaki, and the Struggle to End Nuclear Proliferation,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 33-1-09, August 17, 2009.