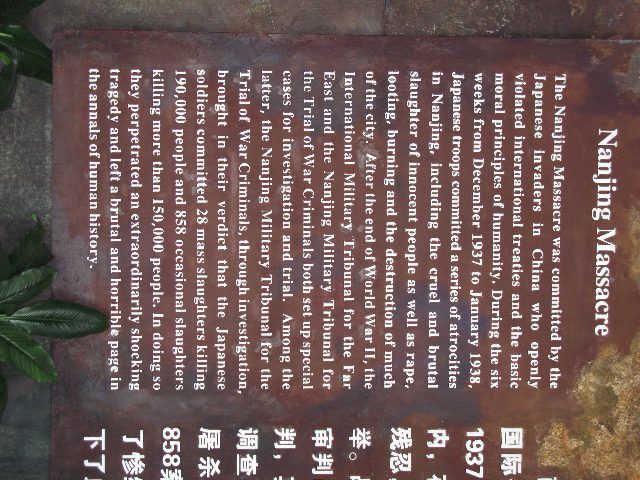

Nanjing’s Massacre Memorial: Renovating War Memory in Nanjing and Tokyo

Jeff Kingston

On a scorching July 7, 2008, officers of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces visited Nanjing for an artillery demonstration, a visit barely mentioned in the Chinese media even though it was the first time Japanese soldiers had returned to the scene of the crime since Japan surrendered in 1945. Unlike in recent years, there were no special commemoration rites on this anniversary of the 1937 Marco Polo Bridge incident. This reflected the Chinese leadership’s decision to turn down the heat on history in the wake of President Hu Jintao’s spring 2008 visit to Japan and the subsequent inking of an agreement on gas field development in disputed maritime territory near the contested Senkaku/Diaoyutai Islands. [1]

Indeed, since Prime Minister Koizumi left office in 2005, the Chinese government has made improvement of bilateral ties a priority. Prime Minister Wen Jiabao visited Japan in April 2007 and made a conciliatory speech lavishing praise on Japan’s post-WWII peaceful development, expressing gratitude for Japan’s generous assistance to China and acknowledging Japan’s apologies for wartime aggression. Televising this speech in China indicates that the state is trying to calm widespread anti-Japanese animosity among the people. Leaders in both nations reckon that too much is at stake to hold the bilateral state relationship hostage to the past, but the political context in which war memory is contested remains fluid. Whether the Chinese leadership can insulate contemporary relations from popular anger over the shared past remains uncertain and depends on factors beyond its control.

In the recent past, survivors gathered at Nanjing’s Massacre Memorial (NMM) to bear witness to the suffering of victims, tapping into and elaborating on the narrative of national humiliation that is central to national identity in modern China, a nation that keenly recalls its bainian guochi, “one hundred years of humiliation” at the hands of foreign powers. [2] Now, as China celebrates its debut as a major power with the staging of the Olympics and as it works to repair relations with Japan, the state seeks to shift the national humiliation narrative to the backburner. Many people, however, remain vigilant supporters of this narrative, constraining the leadership’s diplomatic and reconciliation initiatives. Outbursts in 2004 at the Asia Cup soccer tournament hosted by China and on the streets of Shanghai in 2005 suggest that anti-Japanese sentiments are a potent factor keeping the state’s reconciliation initiatives on a short leash and subject to public scrutiny and criticism. Patriotic education in China focusing on Japan’s wartime misdeeds and the CCP’s crucial role in defeating the Japanese ensures that younger Chinese are aroused over this history. The combination of this patriotic education and the actions and words of Japan’s conservative elite convince many Chinese that Japan remains unrepentant and evasive about its war responsibility, thus limiting the ability of the state to maneuver and compromise over history.

In light of these contemporary concerns, noncommemoration of the Marco Polo Bridge Incident in 2008 is striking given that the exchange of shots in 1937 served as a pretext for Tokyo to launch the large-scale invasion that ignited the Sino-Japanese War of 1937-45. Later that year, on December 13, 1937, Japanese troops entered Nanjing and unleashed a reign of terror, executing POWs and civilians, raping women by the thousands while burning and looting the city. The rampage extended over the next six weeks, leaving the once grand capital of China a shattered and smoldering husk. [3]

Bronzes in front of NMM depicting victims caught up in the Japanese maelstrom.

Mother and dead child in bronze nearly as tall as the NMM.

Competing Narratives

Nationalist narratives of war memory in Japan and Çhina have recently been refurbished. Renovation of the Yûshûkan Museum, on the grounds of Yasukuni Shrine where Japan’s war dead are venerated, was completed at the end of 2006 and renovation of the NMM was completed at the end of 2007. The NMM draws attention to the horrors inflicted in ways that are bound to make Japanese visitors uncomfortable. The rapt crowds gathering around some of the more gruesome displays attest to the allure of gore, and may well tap into and inflame anti-Japanese sentiments. But whether this translates into a nationalism the state can mobilize in support of its agenda is hardly certain. While emphasizing the barbarous actions of the Japanese invaders, the central message the NMM seeks to convey—a plaque near the beginning of the exhibit spells this out—is that China must modernize and grow powerful and rich because it is backward countries that endure such indignities and horrors. To get rich is not only glorious, it is also the basis for security.

Never forget national humiliation. Group photos are a common sight at the NMM.

Based on my conversations with Chinese visitors, it would be mistaken to assume that everyone embraces this message uncritically in its entirety. The presence of the sign signifies the concern that visitors might ‘miss’ this message. Whether visitors take their cue from the state is hardly certain and overlooks ways in which the narrative of war memory is contested in China within the leadership and between the state and the people. The more than10 million visitors to the NMM since it opened in 1985 attest to its popularity, but it would be a mistake to assume that all visitors come to learn about and reflect on history; there are groups who pass through the facility as casual tourists seeing the famous sights of Nanjing, stopping to pause for group photo sessions outdoors—photos inside are prohibited—sometimes longer than they spend absorbing the displays. It is also possible that many diaspora Chinese, attracted to the “forgotten holocaust” theme in Iris Chang’s book, The Rape of Nanking (1997), share the outrage she felt when she visited the NMM in ways that may overlap, but also differ from those of Chinese residents in China where the politics of identity resonate differently. A Taiwanese professor I met by chance confided that even though he bears no grudges, the NMM is a welcome recognition of the atrocities committed against ‘his’ people by a regime that had long overlooked this dark chapter in favor of trumpeting its own heroic victories against the Japanese.

Central to my argument is that monolithic views of war memory in China and Japan miss the ways that these narratives are contested not only among nations, but also among the citizens of each nation. As Phil Deans points out for China, “ …an important distinction must be made between the state-sanctioned discourse on patriotism and the popular mass discourse on nationalism. ‘Patriotism’ (aiguozhuyi) here is an official position, approved of and supported by the CCP, whereas nationalism (minzuzhuyi) may go beyond the state’s approved and preferred boundaries of discourse.” [4]

Tokyo and Nanjing are only three hours distant by plane, but in terms of public history and war memory they are poles apart. Yet there are also forces working toward reconciliation over the shared history of China and Japan. The 2006 establishment of a bilateral Sino-Japanese history panel to develop a mutually acceptable narrative, sixteen years after a similar Korea-Japan panel was launched, is a state-led gambit to shape public discourse over history. However, this panel seems unlikely to resolve fundamental disputes over what happened and why, or to muzzle discordant voices in either country.

Although the political leadership in both nations has decided that contemporary relations should not be held hostage to history, and are in fence-mending overdrive, several Chinese told me that there is little popular support in their country for such efforts. The emergence of history activists in China from the mid-1980s means that the state is no longer able to turn down the volume on history as effectively as it could in the past. Indeed, popular outbursts about historical controversies undermine and circumscribe state initiatives. As one Nanjing-based scholar explains, reconciliation must be based on recognition of what happened and there are too many troubling signs that such recognition is absent among too many Japanese. Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo is ground zero for this selective amnesia and a compelling symbol of Japan’s incomplete repentance and inadequate contrition.

The narrative of Nanjing in 1937-38 on display at the renovated Yûshûkan Museum on the grounds of Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo is a lesson in the politics of war memory. [5] There one can view a video of Japanese troops raising their arms while bellowing a collective “banzai” from atop Nanjing’s city wall that abruptly cuts to a scene of a soldier ladling out soup for the elderly and young while the narrator explains that the Japanese troops entered the city and restored peace and harmony. Throughout the exhibit, Japan’s invasion of China is portrayed as a campaign to quell Chinese terrorism, a post-9/11 narrative that demonstrates just how much the present impinges on the past. At the Yûshûkan, there is no mention of invasion, aggression, massacres or atrocities committed by Japanese troops in China, or, for that matter, of Japan’s defeat in the war. Indeed, Japanese suffering is the only suffering on display.

A family fleeing in hope of reaching safety.

Visitors confront the iconic 300,000-the number of massacre victims claimed by the Chinese government throughout the exhibits.

Back to the Inferno

Nanjing’s new Massacre Memorial unveiled at the end of 2007 is a sleek but somber tomb-like structure fronted by a moat and several bronze statues depicting the suffering endured by those caught up in the Japanese maelstrom. As one passes the turnstile—admission became free after local protesters complained the museum was profiting from others’ trauma—eyes are drawn across an expanse of gravel to a long black marble wall flanked on the left by a towering cement cross decorated with the dates of the massacre and a large bell on the right. On the wall the iconic number 300,000 is emblazoned and incised in several languages. This is a recurrent image throughout the exhibit, one that insists on the number of victims. Inside there is a chamber where visitors can hear the amplified sound of a drop of water every twelve-seconds, said to be the frequency of death during Nanjing’s six-week ordeal. My Chinese companions thought that a bit hokey, but to me it provided a refreshingly subtle contrast to the screams of torture one hears visiting the old Seodaemun jail in Seoul once run by Korea’s colonial masters.

Visitors descend into the museum, a mood-transforming experience as the past is exhumed and the inferno relived. Down the walkway visitors first confront a replica of the city walls with the sounds of bombardment, air raid sirens wailing, anti-aircraft guns blazing and a video of Japan’s attacking bombers. From this sensory assault, one proceeds to a tranquil darkened room with a reflecting pond shimmering with electric “candles” over which projected images of victims’ faces float towards the visitor, beneath a ceiling glowing with the talismanic 300,000, as a bell solemnly tolls.

Projected faces of victims float across a pond shimmering with candles beneath a glowing reminder of the death tally.

A sign explains: “A human holocaust: An Exhibit of the Nanking Massacre Perpetrated by the Japanese Invaders.” Here, Iris Chang’s legacy resonates loudly as the NMM appropriates her central and controversial metaphor; the subtitle of her book is: “The Forgotten Holocaust”. The NMM ensures it is no longer forgotten. Interestingly, the holocaust theme was absent from the original NMM. The displays of photographs, newspaper articles, diary excerpts and artifacts trace the three hundred kilometer trail of sorrow and pillage from Shanghai to Nanjing, with a video of the aerial bombing projected overhead. What happened to the citizens of Nanjing, and to captured and surrendered Chinese soldiers, are richly featured, leaving visitors in no doubt about the scale of the destruction as the Imperial Armed Forces raped, looted and burned their way from the Shanghai littoral all the way to Nanjing. What happened there then is understood here as a culmination and concentration of the malevolence witnessed all along the invasion route. Perhaps responding to the Yûshûkan’s post-9/11 narrative, and with far greater justification, the NMM portrays Japanese troops as terrorists.

The massacre remembered at the NMM

Bronze attesting to a common crime committed by the Japanese troops in Nanjing and elsewhere.

Chinese father and son look at bronze depicting familiar sight in December 1937 of relative carrying dead and maimed relatives away.

One unexpected display shows the Kuomintang (KMT) forces that defended and then abruptly abandoned the capital, leaving its remaining denizens to their fate. This display was not in the original NMM, only appearing from the mid-1990s. Nanjing was the Nationalist capital and the massacre was, therefore, a story in which the CCP has no role. War memory during the Mao era featured examples of heroic resistance by the CCP, so Nanjing was pushed to the margins of war memory discourse. Nanjing based scholars recall that a study on the Nanjing Massacre by local researchers was suppressed in the early 1970s. It is only with the emergence of a parallel victim’s narrative in the post-Mao era that Nanjing gained greater prominence in the narrative of war. [6]

It is striking that the newly included KMT display avoids recriminations or schadenfreude about the KMT’s sudden abandonment of the city to the mercy of Japan’s Imperial Armed Forces. The Taiwanese professor I met on a river cruise said he was pleasantly surprised by the impartial inclusion, pointing out that Chinese textbooks tended to dwell almost as much on the misdeeds of the KMT as those of the Japanese. [7] Indeed, visitors learn that the leader of the KMT forces defending Nanjing was General Tang Shengzhi, but the NMM glides over his escape to safety while leaving his troops in the lurch. It is an ignominious story, one featured in abridged form at the Yûshûkan, of top echelon officers abandoning their troops with no notice, leaving many trapped by the encircling Japanese troops. Some tried to flee, many surrendered only to be executed, while others shed their uniforms and tried to blend into the civilian population. Subsequently, Tang enjoyed a distinguished career in the PRC, rising to Governor of Hunan Province. Even in the Chinese translation of Iris Chang’s book, The Rape of Nanking (1997), his reputation is protected as authorities prevailed on the translator to cut a footnote in which she drew attention to his opportunism.

A mass grave site excavated on the site of the NMM.

Among the unremitting gamut of displays, there is also an excavation of a mass burial site with several skeletons piled one upon another, helter-skelter, grisly evidence that was unearthed from beneath the museum. [8] In this gallery of horrors there is a Shooting, Sabering, Burning and Drowning corner that graphically portrays in photographs, confessions, testimony and soldiers’ diaries the means of massacre. We also learn that many of the tens of thousands of raped women were murdered as a standard procedure to eliminate witnesses. On display are some of the victims humiliated as they were forced to pose for pornographic photos by their rapists.

Problematically, the NMM displays include some photographs and representations that have been discredited, providing ammunition for Japanese revisionists who will no doubt seek to discredit the entire enterprise over a few mistaken attributions and misleading displays in the same manner they tried to bamboozle much of the Japanese public about Iris Chang’s book and divert attention away from the mountains of evidence that corroborate her main claims and those of the NMM.

This brings us to the numbers debate. By insisting on the iconic 300,000, the NMM risks playing into the hands of Japan’s revisionists who would like nothing better than a sterile numbers debate diverting attention away from how much is known about the sacking of Nanjing. Moreover, emphasizing the abacus of history diverts scrutiny away from more crucial issues such as why the troops were allowed to run amok for so long and why the cover-up, minimizing and denial persist to this day.

The massacre verdict at the International Military Tribunal for the Far East (Tokyo Trial).

The estimates of victims vary widely and depend a great deal on the time-frame and spatial limits. [9] The higher estimates include victims well beyond the city walls and extend before and beyond the six weeks from Japan’s initial incursion in Nanjing on December 13, 1937. The International Military Tribunal for the Far East sanctioned an estimate of 200,000 victims. In Japan, estimates of Nanjing victims range from zero by those associated with the illusion school who contend that the massacre is a fabrication, to 10,000-50,000 by those who are associated with what is known as the centrist school, a group of scholars who understand that there is no credibility in denial, but some possibility to cloud the debate by minimizing and mitigating the atrocities, to those who accept higher figures. Most Japanese specialists on the Nanjing Massacre accept figures in the range of 80,000 to 110,000 victims, depending on time and place.

The key point is that the atrocities perpetrated in Nanjing and the city environs were the savage standard operating procedure all along the invasion routes from the Shanghai littoral. The invading Japanese troops were forced to live off the land, in practice meaning the routine plundering of villages, rape and murder of women, and a devastating scorched earth policy that enveloped the entire region stretching three hundred km northwest of Shanghai to Nanjing.

This bronze of a beheaded man lies in the courtyard of the Massacre memorial.

Politicizing History

Yang Xiamen, a professor of International Relations at the Jiangsu College of Public Administration in Nanjing, and the translator of Iris Chang’s, The Rape of Nanking (1997), says, “Ironically, thanks to the revisionists (in Japan), the government spent lots of money and time to collect all of this evidence and build this museum to display it.” In his view, one shared by five other Chinese scholars I met, Japanese efforts to minimize, downplay or obfuscate the extent of wartime atrocities and Japan’s responsibility since the early 1980s provoked a Chinese official response and public anger about Japan’s lack of contrition. Yang also suggests that the globalization of human rights discourse in the 1990s sharpened bilateral debate over contentious history issues.

The controversy over history was triggered in 1982 by Japanese media reports concerning the role of the Japanese Ministry of Education in instructing high school textbook publishers to alter the word “invasion” to “advance” in describing Japan’s escalation of hostilities in China from July 1937. [10] Yang acknowledges that specialists in China now know that this incident was misreported, but at the time the textbook issue was part of what Chinese perceived as a larger trend of whitewashing history in Japan. This example shows the power of the media in generating ill will and distorting public perceptions and the difficulties in undoing the damage. Even if specialists in China do understand now that the textbook row was in some respects ‘invented’ by the Japanese press, this does not stop them from citing it as the key incident in the deterioration in relations between China and Japan in the early 1980s. [11] This is not to defend Japanese secondary school textbooks as models of accurate and uncompromising war memory any more than their Chinese or US counterparts, but rather to emphasize how public memory is prone to lingering distortions that resist correction or reconsideration. [12] Moreover, as Ienaga Saburo’s lawsuits stretching from 1965-1997 reveal, even if this particular instance of government interference was inaccurate, there were systematic attempts by the Japanese government and powerful interest groups to downplay Japanese atrocities against a larger backdrop of a conservative-dominated discourse seeking to promote a vindicating and valorizing narrative of war memory that remains offensive to the people and government of China (and many Japanese). [13 ]

Did the Chinese government whip up a unifying anti-Japanese nationalism in the early 1980s to shore up Deng Xiaoping’s legitimacy and deflect attention away from his adoption of controversial market-oriented reforms? [14] At a luncheon roundtable on July 7, 2008, Chinese specialists on the massacre all rejected this view, arguing that the government was not so savvy or prescient to instrumentalize history in this manner. In their view, Japanese whitewashing of the nation’s shared history forced the Chinese government to abandon its emphasis on building a future oriented relationship as evident in Beijing’s agreement, following normalization of relations in 1972, to renounce compensation. They blame attempts by Japanese revisionists to beautify war memory and shirk responsibility for igniting the ongoing bilateral battle over history that is impeding reconciliation.

Although unmentioned in our discussion, the textbook imbroglio did not occur in a vacuum. The ongoing dispute over the Senkaku/Diaoyutai islands flared up in 1978 when members of the Japan Youth Association erected a lighthouse on the disputed territory and conservatives eager to assert a heroic and noble narrative were prominently weighing in on public discourse concerning war memory in Japan. This territorial dispute heated up following the reversion of Okinawa to Japanese sovereignty in 1972 involving a denial of China’s claims, an assertion that assumed greater importance due to the provisions of the 1968 Law of the Sea. The secret enshrinement of Class “A” war criminals in 1978 at Yasukuni Shrine, first reported in Japan in April 1979 and in China in August 1980, also poisoned the atmosphere and undermined goodwill gestures.

Despite the consensus among the Nanjing-based scholars I met, others argue that Deng realized that the success of his modernization agenda in transforming China from a backward, impoverished nation depended on large-scale infrastructure projects, technology transfer and foreign investment. Given Deng’s pragmatic inclinations, invoking history to help China get what it needed from Japan made sense, although this does not mean raising concerns about the shared past is merely instrumental as Japan’s revisionists contend. Clearly, China does have legitimate grievances over the killing of at least 10 million Chinese in addition to widespread devastation that Japan has failed to assuage by remaining obdurate over war responsibility. [15] Using the past to serve the present meant abandoning what Reilly terms “China’s benevolent amnesia towards Japan” and invoking wartime aggression to help pressure Japan to pay the bills by vastly expanding its bilateral economic assistance programs.

Reilly argues that the victimization narrative that emerged in the 1980s bore a strong resemblance to earlier propaganda campaigns. The Chinese were mobilized by the promotion of patriotic education from the early 1980s, reinforced by government-sponsored films and history museums such as that in Nanjing. However, unlike previous propaganda campaigns, the victimization narrative resonated powerfully among the Chinese people for the very good reason that they had endured tremendous suffering, not only under the Japanese, and suddenly found political space and resources to voice their pain. Reilly describes the state-sanctioned groundswell of popular activism in China in the 1980s on history issues that tapped into deeply ingrained memories of wartime suffering and widespread distrust of Japan. [16 ] Thus, just as the Chinese were finding a collective identity in their shared wartime experiences, “the Japanese” (the Japanese image in China tends towards the monolithic with scant recognition of the deep differences that characterize war memory there) appeared to be backtracking on history, minimizing what happened, while failing to accept responsibility and express atonement.

In this increasingly tense atmosphere, even small gestures, omissions or slight changes in expression carried enormous implications. Any signs of downplaying the suffering inflicted and Japan’s responsibility therefore only served to reinforce popular images of ‘perfidious’ Japanese. The textbook and territorial controversies thus came at a critical juncture in China’s evolving war memory while Prime Minister Nakasone Yasuhiro’s official visit to Yasukuni on August 15, 1985, the first official visit on this politically symbolic date since the 1978 enshrinement of Class “A “ war criminals, rubbed salt in the wounds. [17]

The Japanese government may be eager to declare an end to the postwar era and assert an identity free from the baggage of the shared past— indeed this was Prime Minister Koizumi’s aspiration in trying to make Yasukuni visits ‘normal’— but its neighbors show no signs of letting Japan off the hook of history any time soon.

This is precisely because history issues are far too useful at home, because they box Japan in diplomatically, and also because the Japanese state has waffled about its war responsibility. The enormously popular NMM keeps the past alive and ensures that it is examined and that Japan’s responsibility for crimes against humanity is remembered.

Currently, as the Chinese state tries to insulate contemporary relations from popular anger over history, it finds that it is not so easy to get the genie back in the bottle. Patriotic education and state sanctioned history activism since the 1980s politicized history at the grassroots, ensuring that the younger generations with no first hand experience of the invasion are keenly aware and aroused about their nation’s shared history with Japan. With the spread of the Internet they have a powerful tool to contest history issues and now have a social basis in China’s growing middle-class. [18]

It is important to emphasize that insisting on Japan assuming responsibility for committing atrocities is not merely playing the history card. China, after all, suffered enormously from Japanese depredations and reactions at the elite and mass level are more than an instrumental tactic in support of a wider foreign policy agenda. Japanese revisionists harp on how China’s leadership instrumentalizes war atrocities such as the Nanjing massacre, but this glosses over the very real suffering inflicted and serves to reinforce Japan’s negative image as a country unable to demonstrate remorse and contrition over horrific acts. The Japanese have handed the Chinese the hammer of history by failing to fully acknowledge and assume responsibility for what happened so it is not surprising that the Chinese use it.

A baby suckling at the breast of a dead mother.

Lessons of History

The NMM is much more than a gallery of horrors and does try to suggest lessons to be learned, but it is not certain that chief among those lessons is patriotic duty. Although Buruma argues that the memorial at the time he visited in 1990 before the recent renovations seemed designed to evoke Chinese patriotism, this seems an inadequate interpretation now, two renovations later, because it fails to distinguish between state patriotism and popular nationalism. [19] The renovated and expanded NMM is a splashy, spacious and well-maintained multi-media affair bearing little resemblance to the ‘sad, ill-maintained” site he recalls. [20] Similarly, the Yûshûkan Museum, which used to look like a neglected antique warehouse when I first visited in the late 1980s, now is a state of the art museum. None of the Chinese who accompanied me on a tour or others I questioned agreed with Buruma’s assessment. Visitors feel sadness and anger, and seem more likely to emerge from the museum convinced that the Japanese are truly barbaric rather than embrace a patriotism beholden to state directives.

In contrast with the Yasukuni Shrine, which has an ambiguous relationship with the state as a private religious institution that serves as a national memorial for the war dead, the NMM is unambiguously linked with the state and reflects the government’s agenda. It was built in the early 1980s at a time when relations with Japan were frayed over history issues. Then (and now) Chinese believe that Japan is in denial and incompletely contrite about the consequences of its aggression in China. The NMM fits with the state-sanctioned shift in war memory in the 1980s towards emphasizing Chinese victimization, a counter to the noble sacrifice narrative espoused at Yasukuni Shrine.

The most recent NMM renovation took place in 2006-2007, in the wake of Koizumi’s controversial tenure (2001-2005) when bi-lateral relations sank to a postwar nadir due to his six visits to Yasukuni Shrine. The renovation serves as a riposte to the Yûshûkan’s Nanking narrative of denial, official adoption of the hinomaru flag and kimigayo anthem, the 2006 revision of the Fundamental Law on Education emphasizing patriotic education, public discourse about amending Article 9 of the Constitution and the retreat of Japanese textbooks in 2005 from the more forthright representations of the shared past that began to emerge in the 1990s. For example, in 1997 all junior high school textbooks gave high estimates for the number of Nanjing victims while those published in 2005 mostly avoid citing the number of victims and the “massacre” is once again referred to as an ‘incident’. [21]

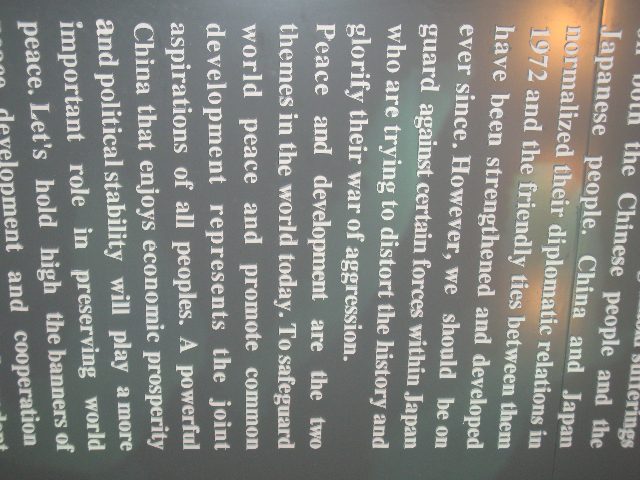

This sign at the NMM draws attention to the role of revisionists, here referred to as “certain forces”, in stirring controversy by distorting history.

The renovated NMM does attempt to challenge monolithic images of Japan by drawing attention to the role of revisionists in provoking contemporary disputes over history, but given the surrounding exhibits and prevailing stereotypes that is expecting a lot from one panel. Perhaps small gestures are as far as the state risks going in modestly toning down the anti-Japanese tenor of the NMM. Chinese government officials, party leaders and intellectuals need to look over their shoulders lest they spark public ire by being seen to be too soft on Japan; the Internet and the socio-political consequences of modernization endow history activists with the means, autonomy and space to pressure the state. Displays about Japanese politicians visiting Yasukuni Shrine and Japanese textbook content update negative images of Japan and ensure that the NMM is not just about the past. Requests in early 2008 by Japanese revisionists for changes in some of the NMM exhibits were studiously ignored. In contrast, the Yûshûkan revised a display blaming FDR for provoking war with Japan to revive the US economy in response to criticisms by George Will, a conservative columnist in the US. Subsequently, and quietly, revisions were also made sometime in 2007 to a panel describing Nanjing, removing an offensive reference to the Japanese troops restoring order in December, 1937 which used to conclude: “Inside the city, residents were once again able to live their lives in peace.” [22] It is intriguing that there was significant media attention to the changes in the FDR panel while the revisions to the Nanjing panel were not publicized and remain overlooked.

As Reilly points out, the state has lost control of popular discourse over history and the emergence of history activists threatens the state monopoly over shaping and expressing war memory. These activists do not determine policy, but they do constrain public debate about war memory and Japan. As Deans argues, “While the Chinese leadership appears to want to pursue a pragmatic policy towards Japan, the mobilization of the historical legacy in the context of popular Chinese nationalism constantly limits the ability of the Chinese leadership to develop and maintain a rational relationship.” [23] Thus, in assessing the NMM it is crucial to go beyond the monolithic message the state wants to convey and explore how individuals understand the memory and meaning on display.

Cindy Zhang, a twenty-two year old Chinese undergraduate studying in Nanjing, confided that the NMM had not aroused her patriotism at all. In the following passages excerpted from an email, she shares her reactions following her first visit while accompanying me on July 7, 2008:

“What disappointed me most about the memorial was that I had expected the exhibition to be condensed and focused, but, as it turned out, things were just the opposite. Although much disappointed, I had to give the memorial the right to be huger than necessary – were it not so huge, it would have been “politically incorrect” in some sense.”

Here, Cindy challenges the Nanjing taboo, suggesting that the NMM is influenced by political correctness and is a bit more than it needs to be. Although she does not elaborate on whether this is in terms of state preferences or popular sentiments, it is clear that she is aware of the wider context in which history is being depicted, contested and possibly manipulated. She adds,

“After the visit, I often wondered why I was not the least touched or moved by the exhibition. One reason is that I was already familiar with that history so that nothing on display made me feel aghast or strike me as particularly overwhelming. I have watched the movie Schindler’s List for over a dozen times; every time I watched it, I cried my soul out. But I never shed a tear for books or movies related to the Nanjing Massacre. I have been intentionally keeping myself at an emotional distance from the Massacre not only to prevent myself from being crushed by the cruel history but also to keep my mind cool and unaffected so that I can analyze the history in a rational way rather than let my perception be overwhelmed with and misled by too much emotions.

Here, Cindy refers to the contemporary context of war memory and her desire to remain aloof from the fray, resisting the NMM’s grisly but powerful appeal to emotions.

In closing she writes:

“As for the relationship between the Chinese and the Japanese, I would like to share some of my thoughts. To begin with, neither side should take the Massacre too personally. When people take things personally, their emotions gain over their reason, giving rise to unjustified hatred, which often leads to calamity. In about thirty years, all people who once lived to have any kind of personal experience about the Massacre will be dead. The future relationship between the Chinese and the Japanese in regard to the Massacre solely depends on how people who have no personal experience of this matter view and interpret it. I suggest that both the Chinese and the Japanese accept the Massacre as an established historical fact, try to analyze it in an objective manner and draw up schemes to prevent similar calamities from happening. I believe that the national characteristics of the Chinese and those of the Japanese played crucial roles in the Massacre. In the light of this, a thorough and in-depth analysis seems particularly important.

I would also suggest that China, including its government and its people, stop assuming the role of a once scarred victim and stop [emphasizing] its old tragedy too frequently. If one indulges in the past, no matter good or bad it is, one loses hold of the present; the past is to be learned and remembered, not to be a burden that hinders the march into the future. As for the Japanese, their national characteristics contain some particularly dangerous elements that are likely to result in calamities like the Massacre. Hopefully, they can face those elements with a positive attitude.”

Cindy’s detached perspective on history may not be representative, but suggests that monolithic images of the Chinese state manipulating history and stoking patriotism are misleading, overlooking the reality of individuals assessing history on their own terms. Her point about the need for China to turn away from the wailing wall of the past is reassuringly subversive even if again it may not be representative.

Towards the end of a numbing array of multi-media displays, three hours in a fast-paced tour, there is a room with a battery of eighteen video monitors that show films and documentaries about the massacre, although not the recent Japanese film that denies it happened. Alongside, there is a twenty-by-twenty meter archival wall with folders containing what information is known about the documented deaths in Nanjing 1937-38. It is a wall that insists that there is much to answer for and overwhelming evidence that Japanese forces perpetrated extensive crimes against humanity, much of it drawing on the testimony and eyewitness reports of Japanese soldiers and journalists.

It is an imposing edifice that Japanese revisionists have tried to undermine by pointing to small flaws, mistaken attributions and exaggerations. They try to discredit the victims’ “forest” of evidence by grasping at branches on the “trees”. [24] Sadly, the discourse over Nanking has bogged down in endless debates over exactly how many civilians, combatants and POWs were killed by Japanese soldiers. [25]

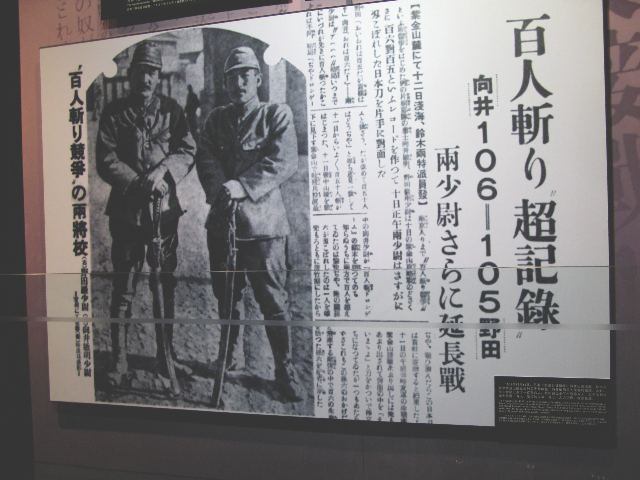

What is clear is that an inordinate number of civilians and unarmed POWs were executed in cold blood, not in the heat of battle as apologists assert. Moreover, Japanese officers and officials at the time systematically sought to cover up the very crimes that perpetrators, surviving victims, officials and observers have all acknowledged. The 100-man beheading contest attributed to two Japanese officers heading for Nanjing, and featured at the NMM, was a media invention aimed at stirring enthusiasm for the war and selling more newspapers to a hero-hungry public. [26] However, the inclusion of this concocted tale serves a purpose because it highlights what the media thought the Japanese public craved, implicating them in the horrors that ensued.

A copy of a Japanese newspaper article about the 100-man killing contest is on display

The final image as one emerges from the NMM is a towering obelisk inscribed with PEACE (in English and Chinese) that flickers in a reflecting pool. It is a jarring juxtaposition to the violence and mayhem featured inside, an unconvincing accessory that fails to persuade. None of the Chinese who accompanied me on this tour felt the message either masked or matched the museum’s intentions and impact. One young Chinese man bluntly confided that the museum left him angry, reinforcing his already hostile views towards the Japanese. He said, “Yes we like Japanese technology, gadgets and machines, but not the people. At that time they always referred to us Chinese as pigs, but here we see who was really an animal and inhumane.”

The Peace tower doesn’t seem to fit with the NMM’s intent or impact

The lessons of history at the NMM.

Monolithic Myths, Fragile Relations

In China and Japan, public discourse reproduces and reinforces monolithic images of the other that are broadly negative. The central problem for Japanese revisionists is the impossibility of reconciling their narrative of noble sacrifice with the gruesome evidence of cavalier slaughter and rape as presented at the NMM. Their strategy depends on instigating and instrumentalizing Chinese grievances over the shared past. Revisionist emphasis on denying, minimizing, mitigating and otherwise shifting responsibility for the atrocities committed by Japan’s Imperial Armed Forces 1931-45 may not gain much popular support in Japan, but does cast a long shadow over relations with China and ignites anti-Japanese sentiments. Provoking the Chinese over history naturally produces anti-Japanese outbursts in China that amplify anti-Chinese nationalism among Japanese in ways that play into the hands of Japan’s revisionists. In short, inflaming the Chinese pays handsome dividends for revisionists, and so they act accordingly.

Thus, while leaders in both countries seek to build mutually beneficial, forward-looking relations, their efforts remain fragile and vulnerable. In Japan, a country with numerous cases of home-grown food-safety problems that affect millions of consumers, tainted frozen gyoza (dumplings) imported from China that affected ten Japanese consumers in the winter of 2008 sparked an anti-Chinese, media-induced hysteria of epic proportions. Positive attitudes toward China imploded in the wake of the gyoza hysteria and the media was still making it an issue during the G8 Summit in July, 2008. The LDP was roundly thrashed in the national press for not immediately disclosing all it knew about ‘gyoza-gate’ in the run-up to the Olympics, essentially found guilty of placating the Chinese at the expense of Japanese consumers. Hu Jintao and Fukuda Yasuo might have grander visions for bilateral relations, but can not ignore or escape such populist brushfires.

This latent grassroots hostility can easily erupt precisely because the media in both countries sensationalizes the present and the past. In 2003, 300 Japanese businessmen were caught up in a raid involving 400 prostitutes at a hotel in Guangdong for holding an alleged ‘orgy’ on September 18, the anniversary of the Mukden Incident of 1931. While not condoning the executives’ conduct, enforcement of laws against prostitution in Guangdong appear to be quite lax in general while the notion that these inebriated salarymen were trying to make a political statement is ludicrous. The Chinese media, however, whipped up popular anger among an incensed population who were led to believe that the timing of the ‘orgy’ was a calculated insult.

Where does the NMM fit into this public discourse on history? Of course there was considerable media attention at the unveiling of the renovated NMM in December 2007 commemorating the 70th anniversary of the massacre, but films, television dramas, textbooks and the Internet reach wider audiences. The NMM is more like the repository of “evidence” that buttresses other representations of the Nanjing Massacre. It is ground-zero of Japanese evil, a site that reinforces the perception that Japanese conduct in Nanjing was emblematic of its fifteen-year war in China, a locus of concentrated Japanese malevolence that exists to honor local suffering and counter Japanese denial. [27]

The NMM draws heavily on testimony and diaries of Japanese soldiers, some of whom were shocked by what they experienced. It also includes an exhibit on Azuma Shiro, a veteran of the Nanjing massacre who wrote forthrightly about what he observed and did back in December 1937-January 1938. The court case he lost over whether some points he made in his account were plausible is seen in China to be typical of Japanese attempts to cavil rather than assume an encompassing responsibility with dignity and remorse. Thus, ambivalence in Japan about the gruesome past has burdened Japanese with the appearance of shirking, explaining why Chinese imagine that denial is more widespread than it really is.

Conclusions

Visitors to the NMM, and the Chinese in general, never learn that a majority of Japanese people do not embrace the valorizing and exonerating view of the war cherished and endlessly promoted by Japan’s revisionist conservative elite. [28] As Seraphim elucidates, the memory battles in Japan are hotly contested, exposing fundamental political cleavages that are central to debates over the past and ensuring that Japan’s ambivalence towards its shared history with Asia draws considerable criticism based on invidious comparisons with Germany.[29]

She correctly asserts that the notion of collective amnesia in Japan regarding war responsibility is, media representations to the contrary, grossly inaccurate, overlooking the vigorous contestations and wide divergence of opinions concerning war memory that abound in post-WWII Japan. Alas, those who espouse narratives of denial and minimization are prominent in the political mainstream and in some influential media in Japan and can not be dismissed as “unsavory crackpots” to borrow Buruma’s felicitous phrase.

Chinese, however, uncritically accept Iris Chang’s monochromatic view of war memory in Japan, endlessly reinforced in the Chinese mass media, suggesting that a majority of the Japanese are in denial about the wretched past and eager to embrace a vindicating narrative. In China there is little recognition of the vibrant scholarship on Nanjing by Japanese researchers who have toiled for decades to present an accurate view of what happened and why. [30] There is also little awareness of the interest groups in Japan that have contested narratives of the wartime past up until the present. There is far greater awareness about conservative politicians’ public denials of the massacre and their extensive involvement in study groups aimed at rebutting the facts of the massacre. The outpouring of Japanese books, films and manga raising doubts about the massacre leads many Chinese to question the sincerity of the joint declaration of November 1998 in which the Japanese government reiterated that, “Japan is keenly aware of its responsibility for the massive suffering and loss inflicted on the people of China resulting from its invasion of China at one time in the past, and expresses its deep regret.“

The revisionists may be a megaphone minority in Japan, but they cast a disproportionately long shadow in China precisely because they are entrenched at the center of state power. The political influence of the revisionists is undeniable even if their views of history are not widely embraced by the Japanese public. Public opinion polls show that a majority of Japanese people reject reactionaries’ insistence on denying and minimizing the atrocities perpetrated by the Imperial Armed Forces, and most think the government should do more to acknowledge war responsibility and atone for the excesses. The textbook written by the Dr. Feelgoods of Japanese history that has garnered so much media attention because it downplays the “bad bits” has been adopted by less than 1% of school boards around the country. Former Prime Minister Abe Shinzo’s egregious attempts to reinterpret the history of comfort women and the battle for Okinawa are part of the reason he is remembered as one of Japan’s most hapless leaders. PM Koizumi’s visits to Yasukuni were criticized by a who’s who of the conservative elite, including five former prime ministers and the conservative Yomiuri Shimbun. It is understandable why the Chinese government refrained from summit meetings between leaders and limited other high level government exchanges during Koizumi’s tenure, but it is also important to recognize that official actions and popular sentiments are often discordant in both countries, especially regarding issues of war memory and responsibility.

Just as Japanese have much to discover about the tensions in China between the state and grassroots history activists over war memory, the Chinese people can learn much from understanding the realities of Japanese public discourse over war memory. Chinese may be surprised to learn that they can find common ground with many Japanese over war responsibility. The media tends to sensationalize this discourse and generates misperceptions that fan hostility. As a teacher I have noticed how much better informed Japanese students are now than they used to be twenty years ago about this shared past. Thus only one of the more than one hundred research papers on Nanjing submitted in my classes in recent years expressed anything but condemnation and contrition. The only sign of contemporary Japanese contrition at the Massacre Memorial, however, are mute, decorative garlands of origami cranes, looking rather forlorn, piled as they are on a shelf visitors hurry past on their way to the exit. Though it may be scant consolation to Chinese that few Japanese seek a national identity rooted in an airbrushed history, knowing this might be a useful step towards reconciliation.

Over 200 footprints of survivors of the massacre are cast in bronze at the NMM.

The NMM serves as a barometer of the evolving discourse over history. Since opening in 1985 there have been at least three significant renovations, the last in 2006-2007 vastly expanding and modernizing the space. Certainly the curator has an eye to drawing visitors and the new multi-media exhibits and tranquil spaces for contemplation have considerable visual and sensory appeal. The NMM grew into a political space created by the shift towards a victims’ narrative in the 1980s and the timing of its construction ties it with the 1982 textbook row. According to some observers, it is also linked with Deng’s desire to raise the ante over history as a means of opening the spigots of quasi-reparations from Japan in the form of economic and technological assistance. In the mid-1990s the NMM brought the KMT into the story line, perhaps reflecting shifting attitudes towards Taiwan and growing confidence. The holocaust theme now on display owes much to Iris Chang’s legacy; German holocaust memorials were not part of the original design or inspiration in the early 1980s. The recent renovation also appears to be a riposte to the renovation of the Yûshûkan Museum the previous year in which the revisionist narrative vindicating and valorizing Japan’s ‘noble quest’ prevails. Indeed, the NMM appropriates the post-9/11 theme of the Yûshûkan that justifies Japan’s actions in China in terms of quelling terrorist threats, by referring to the Japanese invaders as terrorists. In addition, the NMM renovation took place at a time when bilateral relations were in a deep freeze caused by PM Koizumi’s six provocative visits to Yasukuni Shrine between 2001 and 2005. Since Koizumi’s departure, leaders in both countries have emphasized thawing relations and nurturing the habits and inclinations of cooperation, consultation and expanded exchanges, but there is no denying a hostile environment. Japan’s official adoption of the hinomaru flag and kimigayo anthem, legislation compelling patriotic education and efforts to revise the Peace Constitution are provocations that link the current state with the wartime regime. The impact on Chinese perceptions, both official and popular, should not be underestimated and help explain why the NMM remains relevant and why the renovations are linked to an anticipated bid for World Heritage status. Most of the survivors will be gone by the 80th anniversary in 2017, but the NMM will remain as a poignant reminder of the nation’s ordeal and the perils of nationalism, then and now.

Jeff Kingston is Director of Asian Studies, Temple University (Japan Campus) and a Japan Focus associate. He wrote and photographed this article for Japan Focus. He is the author of “Burma’s Despair, Critical Asian Studies, 40:1 (March 2008), 3-43, several recent articles on East Timor and Japan’s Quiet Transformation: Social Change and Civil Society in the 21st Century (Routledge, 2004). Posted on Japan Focus on August 22, 2008.

Notes

[1] It is striking that on July 7, 2004, Denton writes, “… special ceremonies were held, including personal oral narrations by living witnesses.” This of course occurred during Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro’s term in office (2001-2005) when he heated up the bilateral history war and froze diplomatic exchanges by repeatedly visiting Yasukuni Shrine, six times in total. Four years and two Japanese prime ministers later, the frenzied Chinese response to Koizumi’s provocations has abated, and key dates in the two nations’ shared history are no longer natural opportunities to poke the wounds of history and engage in recrimination. See Kirk Denton, “Heroic Resistance and Victims of Atrocity: Negotiating the Memory of Japanese Imperialism in Chinese Museums”, Japan Focus, Oct. 17, 2007.

[2] On national humiliation as identity and nationalist contestations see Peter Gries, China’s New Nationalism: Pride, Politics and Diplomacy. University of California Press, Berkeley, 2004.

[3] The documentary by Bill Guttentag and Dan Sturman, Nanking, (Thinkfilm, 2007) evokes the horrors and devastation of the Japanese invasion and ensuing onslaught. This documentary focuses on the role of western residents of Nanjing in establishing an International Safety Zone for noncombatants with readings from their letters and diaries spliced with archival footage and interviews with survivors.

[4] Phil Deans, “Diminishing Returns”: Prime Minister Koizumi’s Visits to the Yasukuni Shrine in the Context of East Asian Nationalisms”, East Asia (2007) 24, pp. 269-294 (287)

[5] For a discussion of the politics of war memory in Japan see, Jeff Kingston, “Awkward Talisman: War memory, Reconciliation and Yasukuni”, East Asia, 24 (2007), pp. 295-318. For the politics of war memory in China, see Mark Eykholt, “Aggression, Victimization, and Chinese Historiography of the Nanjing Massacre”, in Joshua Fogel, ed., The Nanjing Massacre in History and Historiography, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2000, pp. 11-69.

[6] Denton, op.cit., elucidates the evolution of war memory in China from heroic resistance to victims of atrocity. In Nanjing, for obvious reasons, it could only be about victimization. In interviews with six Chinese scholars specializing in the Nanjing massacres, there was no support for this analysis of evolving war memory. They see no clear dichotomy between narratives of heroic resistance and victimization in public history as described by Denton, arguing instead that both perspectives are inextricably intertwined, along the lines that Gries argues.

[7] Zhu Jianrong confirms this perception, arguing that a content analysis of Chinese textbooks indicates that there has not been any increase of anti-Japanese content in the 1990s contrary to prevailing misperceptions. Zhu Jianrong, “Japan’s Role in the Rise of Chinese Nationalism: History and Prospects”, in Tsuyoshi Hasegawa and Kazuhiko Togo, ed., East Asia’s Haunted Present: Historical Memories and the Resurgence of Nationalism. NY: Praeger Security International, 2008, pp. 180-189. Zhu draws on an unpublished study of Chinese textbooks cited on p. 183.

[8] The old museum also displayed excavated skeletons, but they had been laid out to make them more easily recognizable. The new excavations left the skeletons undisturbed to better convey the chaos of the mass burials and make the evidence more compelling precisely because it does not appear “constructed”. This “hot” evidence also is aimed at creating a sense of immediacy to convince skeptics that the museum site is indeed a mass graveyard where Japanese hoped to bury their crimes. Interview, Yang Xiamen, July 7, 2008.

[9] For an assessment of the numbers debate see Fujiwara Akira, “The Nanking Atrocity: An Interpretive Overview,” Japan Focus, Oct. 23, 2007.

For an intriguing discussion of atrocities and how they are remembered (or not) see Mark Selden, “Japanese and American War Atrocities, Historical Memory and Reconcilation: WWII to Today,” Japan Focus, Apr. 15, 2008.

[10] On the idea of the museum arising from the 1982 textbook controversy see Daqing Yang, “Mirror for the Future or the History Card? Understanding the ‘History Problem’ “ in Marie Soderberg (ed.), Chinese-Japanese Relations in the Twenty-First Century: Complementarity and Conflict. (London: Routledge, 2002). The misreporting of the revision by Nippon Television and subsequently the Asahi Shimbun is extensively analyzed by Caroline Rose, Interpreting History in Sino-Japanese Relations, Routledge Curzon: London, 1998. For an overview of the textbook controversy see Claudia Schneider, “The Japanese History Textbook Controversy in East Asian Perspective”, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science (May 2008), 617, pp.107-122. Also Daiki Shibuchi, Japan’s History Textbook Controversy: Social Movements and Governments in East Asia, 1982-2006. Discussion Paper #4 (March 2008), Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies.

For details and analysis of Ienaga Saburo’s pioneering lawsuits challenging state censorship of textbooks, see Yoshiko Nozaki and Hiromitsu Inokuchi, “Japanese Education, Nationalism, and Ienaga Saburo’s Textbook Lawsuits”, in Laura Hein and Mark Selden, ed., Censoring History: Citizenship and Memory in Japan, Germany and the United States. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2000, pp. 96-126.

[11] The textbook controversy was invoked at a luncheon roundtable with six Chinese scholars July 7, 2008.

[12] There was a trend in the mid-1990s towards a more forthright reckoning in Japanese secondary school textbooks, but this provoked a backlash among the “Dr. Feelgoods” of Japanese history and the establishment of the Society for History Textbook Reform (Atarashi Rekishi Kyokasho o Tsukurukai, hereafter referred to as Tsukurukai). This group favors an exculpatory and valorous historical narrative. As part of Tsukurukai’s efforts to shape public history and war memory, it published a textbook in 2001 (revised in 2005) for junior high schools. Extensive media coverage both in Japan and internationally conveys an impression that this textbook reflects the public mood and that Japanese are seeking an identity grounded in a more assertive nationalism based on an unapologetic view of Japan’s shared history with Asia. Moreover, as Sven Saaler concludes, the Tsukurukai text has significantly shaped public discourse over this past to the extent that other publishers have revised their textbooks by retreating from the somewhat more critical mid-1990s narratives and have moved closer towards the Tsukurukai narrative. The media hype translated into unusually high sales of the textbook, including large volume sales to conservative organizations, reinforcing and amplifying its influence over public discourse. Bestowing best-seller status on this text then feeds the media frenzy and stimulates more curiosity. Sven Saaler, Politics Memory and Public Opinion: The History Textbook Controversy and Japanese Society. Deutsches Institut fur Japanstudien: Munich, 2005. Also see David McNeill and Mark Selden, “Asia battles over war history: The legacy of the Pacific War looms over Tokyo’s plans for the future,” Japan Focus, April 12, 2005.

and Yoshiko Nozaki “The Comfort Women Controversy: History and Testimony,” Japan Focus, July 29, 2005.

[13] See Franziska Seraphim, War Memory and Social Politics, 1945-2005. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press, 2006. [14] For analysis of this perspective and the rise of history activism see James Reilly, “China’s History Activism and Sino-Japanese Relations”, China: An International Journal 4.2(2006), pp. 189-216. On Deng’s desire to embarrass the Japanese and protect his back from domestic opponents see Ian Buruma, The Wages of Guilt : Memories of War in Germany and Japan, NY: Farrar, Straus Giroux, 1994, p. 126. This interpretation is rejected by Zhu Jianrong, op.cit., who holds that Deng sought good relations with advanced industrialized nations including Japan and avoided making an issue of the past because he knew China needed Japan’s assistance to modernize. He argues that Jiang Zemin played a key role in whipping up anti-Japanese nationalism in the 1990s.

[15] Reilly, Seraphim and Deans, op.cit., all argue that China has played the history card to extract quasi-reparations.

[16] According to Reilly, the genie of history activism unleashed by the state morphed into an autonomous grassroots movement the state could no longer control and more recently into what he terms oppositional activism. op.cit.

[17] The Treaty of Peace and Friendship with China was ratified in Japan on October 18, 1978, a day after the 14 Class-A war criminals were secretly enshrined at Yasukuni Shrine. Conservatives opposed to normalization of relations with China were also mollified by the passage of the Gengo Law in 1978 that gave legal status to the practice of linking official dates to the year of an Emperor’s reign, i.e. 2008 is Heisei 20. Deans, op.cit., 282.

[18] Zhu, argues that successful modernization has created a large middle class that demands, “…respect from other nations. Nationalism thus acquired a social basis.” Zhu, op.cit., p.184.

[19]Ian Buruma, “The Nanjing Massacre as a Historical Symbol,” in Nanking 1937: Memory and Healing, ed. Feifei Li, Robert Sabella and David Liu (Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2002), pp. 1-9.

[20] Ian Buruma (1994), op.cit., p. 185

[21] Schneider, op.cit., p. 116.

[22] I am indebted to Sven Saaler regarding this point. Personal communication, 8/15/2008).

[23] Deans, op.cit. p. 288.

[24] See Daqing Yang, “The Challenges of the Nanjing Massacre: Reflections on Historical Inquiry”, in Joshua Fogel, ed., The Nanjing Massacre in History and Historiography, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2000, pp. 133-179.

[25] See Takeshi Yoshida. “The Nanjing Massacre” Changing Contours of History and Memory in Japan, China and the US”, Japan Focus, December 19, 2006. Also see Yoshida’s , The Making of the “Rape of Nanking”: History and Memory in Japan, China, and the United States. Oxford University Press: New York, 2006.

[26] For analysis of the alleged contest see Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi, “The Nanking 100-Man Killing Contest Debate: War Guilt amid Fabricated Illusions, 1971-75”, Journal of Japanese Studies 26-2, Summer 2000, 307-340.

[27] For related discussion see Selden, op.cit.

[28] For a more accurate and nuanced assessment of Japanese attitudes and public opinion regarding history see Philip Seaton, Japan’s Contested War Memories: The ‘Memory Rifts’ in Historical Consciousness of WWII. Routledge: London, 2007.

[29] Seraphim, op.cit.

[30]For example see Bob Wakabayashi, ed., The Nanking Atrocity 1937-38: Complicating the Picture. Bergahn Books, NY, 2007.