East Timor ’s Search for Justice and Reconciliation

By Jeff Kingston

[With East Timors President Xanana Gusmao presenting to the United Nations the report of the Commission of Reception, Truth and Reconciliation, Japan Focus presents a revised, expanded and updated version of Jeff Kingston’s earlier report on the issues drawing on interviews with Gusmao, Foreign Minister Jose Ramos-Horta and others. The issues reverberate beyond East Timor and Indonesia to such nations as the United States, Japan and Australia that supported Indonesian repression in East Timor over a quarter of a century from the 1975 invasion. This article reproduces major findings of the report on the Indonesian reign of terror in the final stages of the referendum period and beyond and condemns the failure to act on the part of the US and other powers. The text of the entire Commission report is available from the National Security Archive. Japan Focus]

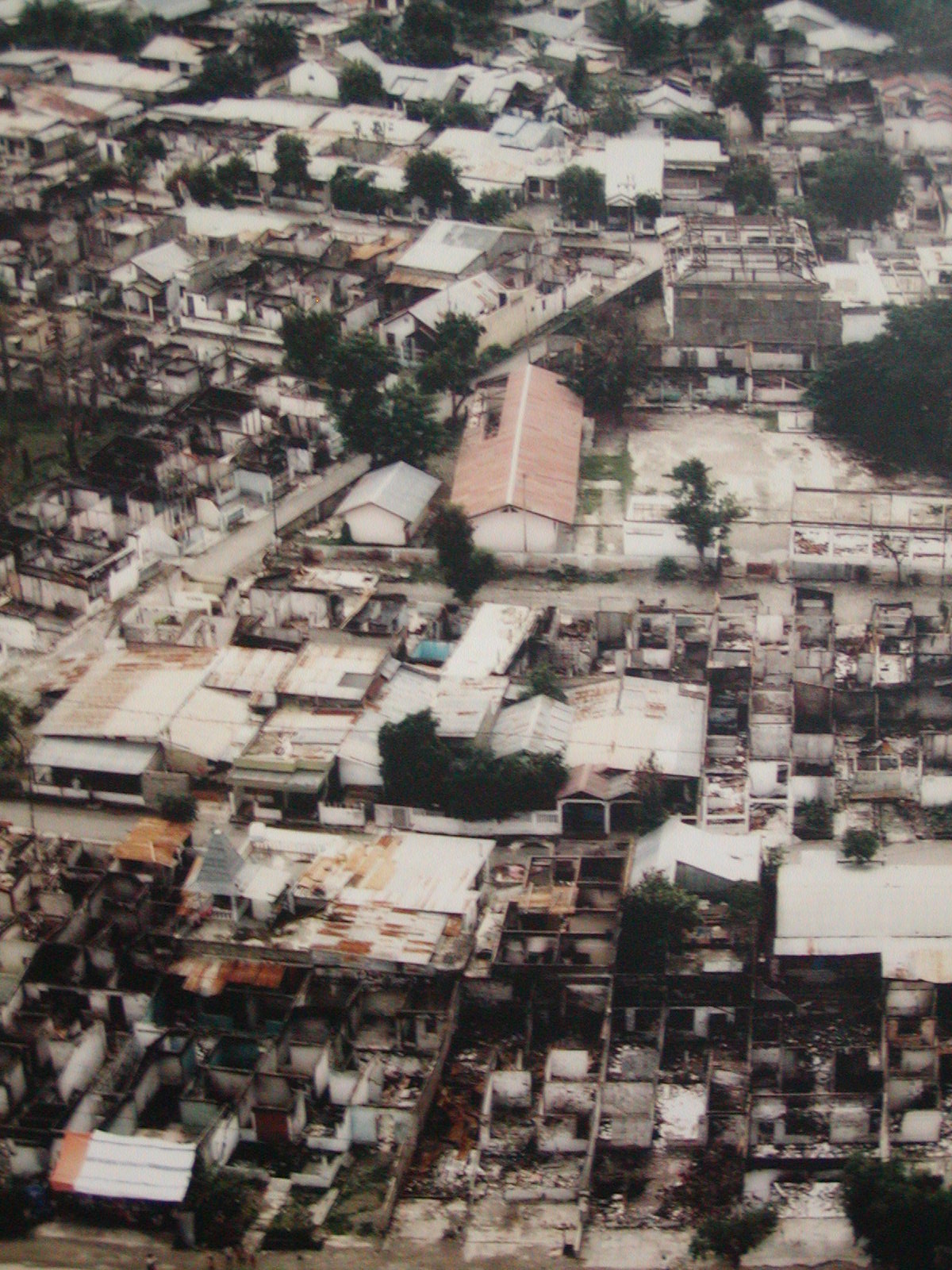

Dili after the attack.

East Timor ’s 924,000 citizens are finding that the truth does not set them free and that justice and reconciliation are elusive. A recent report published by East Timor’s Commission of Reception, Truth and Reconciliation (CAVR is the commonly used Portuguese acronym), estimates that there were a minimum of 102,800 conflict-related deaths and perhaps as many as 200,000 during Indonesia’s brutal occupation between 1975-99. [1] There were ”…approximately 18,600 unlawful killings and enforced disappearances of East Timorese non-combatants perpetrated between 1974-1999.”

The CAVR reports that “…many people died from hunger and illness in excess of the peacetime baseline for these causes of death.” Starvation, rape, torture and resettlement were systematically organized to pacify the island. It finds that “The overwhelming number of these deaths occurred in the years 1977-78…”, and during large scale Indonesian military attacks in the interior and later in Indonesian detention camps and resettlement areas where food and medical care were grossly insufficient. Responsibility for this carnage, in addition to widespread torture and rape, rests largely with the Indonesian military. However, the CAVR also attributes 10% of the toll to internecine violence among the four main East Timorese parties and reprisals against those who collaborated with the Indonesian military.

Finally in 1999, when a referendum on independence was held under UN auspices, the world paid attention to East Timor’s nightmare. Despite widespread intimidation and violence, almost all East Timorese showed the courage to vote and overwhelmingly chose independence from Indonesia. They paid the price. As promised in the event of such an outcome, Indonesian controlled militia razed towns, villages and churches, while brutalizing the population and forcibly relocating as many as 250,000 Timorese to Indonesian-controlled West Timor. The CAVR report, entitled Chega! (Enough!), concludes that there is credible and extensive evidence that planning for and knowledge of this scorched earth campaign extended to the highest echelons of the Indonesian military.

Bringing these high-ranking officers and their goons to justice has been frustrating largely because there has been insufficient political will in Indonesia and the international community to hold them accountable. An Ad Hoc Tribunal established by Jakarta did conduct trials and there were some convictions and sentences, but all but one of these convictions have been overturned on appeal and the remaining defendant remains free while his appeal is pending. In a May 2005 report submitted to UN Secretary General Kofi Annan, a panel of experts criticized this fundamentally flawed judicial process. [2] Not only did the big fish get away, even the designated scapegoats have walked.

On Dec 20, 2005 the CAVR dissolved amidst controversy and recriminations. The President has not yet made the report public generating widespread dismay within East Timor and the international community. In early December he explained to me, ”I accept the report from A to Z and will not change anything. I believe that the public has the right to be informed. We must disseminate it in the proper way. We are not a human rights organization. Everything will be done in the right way in the right time. At the end of January I will present the report to the secretary general in New York and will stop in Tokyo on my return to request financial assistance for a series of workshops aimed at disseminating and socializing it in 2006.” [3] As promised he presented the report to the secretary General on Jan. 20, 2006.

The following excerpts are from the 215 page executive summary.

FINDINGS

*On the function of history: “…our nation chose to pursue accountability for past human rights violations, to do this comprehensively for both serious and less serious crimes…and to demonstrate the immense damage done to individuals and communities when power is used with impunity…our mission was to establish accountability in order to deepen and strengthen the prospects for peace, democracy, the rule of law and human rights in our new nation. Central to this was the recognition that victims not only had a right to justice and the truth but that justice, truth and mutual understanding are essential for the healing and reconciliation of individuals and the nation. The CAVR was required to focus on the past for the sake of the future.”

* Indonesia’s responsibility : “…rests primarily with President Soeharto, but is shared by the Indonesian armed forces, intelligence agencies and the Centre for Strategic and International Studies which were principally responsible for its planning and implementation.”

* On the possibility that rogue elements in the military were acting on their own initiative without the knowledge of superiors in Jakarta: “Throughout the occupation Indonesian military commanders ordered, supported and condoned systematic and widespread unlawful killings and enforced disappearances of thousands of civilians…The sheer number of these fatalities, the evidence that many of them occurred during coordinated operations…and the efforts of domestic and international non-government [organizations] to inform the military and civilian authorities in Jakarta that these atrocities were happening rule out the possibility that the highest reaches of the Indonesian military, police and civil administration were ignorant of what was going on.”

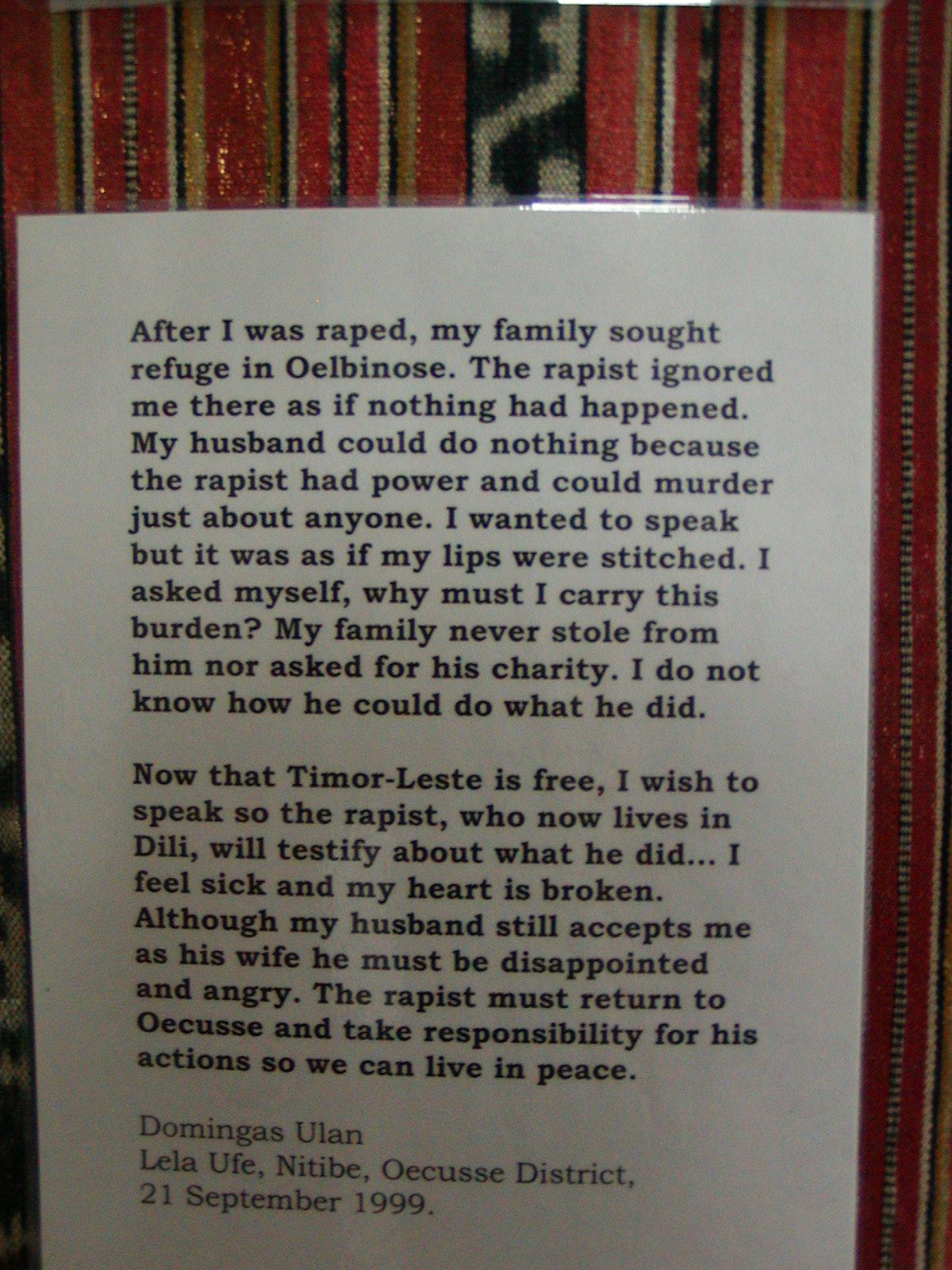

*Sexual violence committed by the Indonesian military was: “…widespread and systematic … in which members of the Indonesian security forces openly engaged in rape, sexual torture, sexual slavery and other forms of sexual violence throughout the entire period of the invasion and occupation.” This involved, “…keeping lists of local women who could be routinely forced to come to the military post…so that soldiers could rape them. Lists were traded between military units.” In addition, “…rapes and assaults were repeatedly conducted inside victim’s homes, despite the presence of parents, children and other family members.” “Often these women were the targets of proxy violence. That is, because the woman’s husband or brother who was being sought by the military was absent, the woman would be raped and tortured, as a means of indirectly attacking the absent target.” The report concludes that sexual violations were used as a tool of terror and degradation involving practices such as, “…forcing prisoners to walk long distances through communities while naked, public rape and multiple instances of rape and torture in military posts…The purpose was also to humiliate and dehumanize the East Timorese people. It was an attempt to destroy their will to resist, to reinforce the reality that they were utterly powerless and subject to the cruel and inhuman whims of those who controlled the situation with guns.”

The impunity enjoyed by the rapists meant, “that the practice of capturing, raping and torturing women was conducted openly without fear of any form of sanction by senior military officers…This impunity could not have continued without the knowledge and complicity of members of the Indonesian security forces, the police force, the highest levels of the civilian administration and members of the judiciary.”

The rapists have fathered children yet provided no support for rearing them. “This was particularly problematic because former victims of rape and sexual slavery at the hands of Indonesian military forces were often considered ‘soiled’ and unsuitable for marriage by East Timorese men and faced ongoing social stigma…. Misperceptions on sexual violence continue to lead to the victimization of women.”

*On the role of militias in the 1999 violence: “In 1999 Indonesian security forces and their auxiliaries conducted a coordinated and sustained campaign of violence designed to intimidate the pro-independence movement…Military bases were openly used as militia headquarters, and military equipment, including forearms were distributed to militia groups.

* Regarding the 1999 referendum: “When the result of the ballot was announced, the Indonesian military and its militia allies carried out its threatened retaliation, to devastating effect, but this time governments were unable to ignore the contrast between the extraordinary courage and quiet dignity displayed by the voters of Timor-Leste and the terrible retribution wreaked by the TNI and its East Timorese partners.”

* Regarding the international community: “In reality key member states did little to challenge Indonesia’s annexation of Timor-Lest or the violent means used to enforce it. Most nations were prepared to appease Indonesia as a major power in the South-East Asian region.”

*On Japanese complicity: “ Japan was Indonesia’s major investor and aid donor and had more capacity than other Asian nations to influence policymaking in Jakarta, but it did not use this leverage.”

* On US responsibility: “ As a Permanent Member of the Security Council and superpower, the U.S. had the power and influence to prevent Indonesia’s military intervention but declined to do so. It consented to the invasion and allowed Indonesia to use its military equipment in the knowledge that this violated US law and would be used to suppress the right of self-determination.”

* The Vatican, despite pleas for support, was, “… concerned to protect the Catholic Church in Muslim Indonesia, maintained public silence on the matter and discouraged others in the Church from promoting the issue.”

* France and the UK: “…increased their aid, trade and military cooperation with Indonesia during the occupation.”

* Australia: ”…did not use its international influence to try to block the invasion and spare Timor-Leste its predictable humanitarian consequences. Australia acknowledged the right of self-determination, but undermined it in practice by accommodating Indonesia’s designs on the territory and opposing independence.”

The CAVR final report found that between 1974 and 1999:

*A vast majority (85%) of the human rights violations directly reported to the Commission were committed by Indonesian security forces acting alone or through auxiliaries.

*Violations were “massive, widespread and systematic.” Indonesian forces used starvation as a weapon of war, committed arbitrary executions, and routinely tortured anyone suspected of sympathizing with pro-independence forces.

*The Indonesian government and the highest commanders of the Indonesian army violated international humanitarian law by targeting civilians.

RECOMMENDATIONS

In addition to various initiatives for community healing, victim counseling, financial aid and memorialization,

- The CAVR calls on the Security Council to establish an international tribunal, “…should other measures be deemed to have failed to deliver a sufficient measure of justice and Indonesia persists in obstructing justice.”

- Based on 8,000 individual statements, and a series of public hearings throughout East Timor, the CAVR concludes that, “…the demand for justice and accountability remains a fundamental issue in the lives of many East Timorese people and a potential obstacle to building a democratic society based upon respect for the rule of law and authentic reconciliation.” It finds that, “Overwhelmingly they have expressed to the Commission that they seek some kind of accountability on the part of the perpetrators, and simple assistance to enable them and their children to participate on an even footing in the new democratic Timor-Leste.”

- Justice and accountability must involve, “Those who planned, ordered, committed and are responsible for the most serious human rights violations [who] in many cases have seen their military and civilian careers flourish as a result of their activities.”

- To promote reconciliation and democratization, Indonesia should strengthen, “…the independence and efficiency of its judicial system in order to be able to genuinely pursue justice and revert the record of impunity that regrettably has been the norm regarding the crimes committed in Timor-Leste.”

- Regarding the bilateral Commission for Truth and Friendship established by Indonesia and East Timor as a means to seek truth and closure, possibly involving amnesty, ” The CAVR believes that nothing should compromise the rights of victims to justice and redress.” The CTF is enjoined to act,

“…with a view to strengthening, not weakening, the chances of criminal justice.” And amnesty should only be granted, “…if this is based on judicial due process consistent with international standards.” This means that those guilty of serious crimes would be ineligible for amnesty.

- Indonesia is urged to revise, “…official accounts and education materials relating to Indonesia’s presence in Timor-Leste to ensure that these give the Indonesian people and accurate and comprehensive account of the period 1974-1999.” Further it should, “…destroy all intelligence files maintained on East Timorese…” and expunge from “… ‘blacklists’ the names of East Timorese and non-East Timorese human rights activists.”

- Reparations are largely the obligation of Indonesia and should include, “business companies which profited from war and related activities in Timor-Lest between 1974-1999.”

- Lasting reconciliation, “…cannot be achieved without establishing the truth, striving for justice, and providing reparations to victims.”

- Reparations: “At least 50% of programme resources should be directed to female beneficiaries.”

- Indonesia , “As the occupying power which committed most of the violations…has the greatest moral and legal responsibility to repair the damage caused by its policies and agents.” However, “If Indonesia is slow to respond…the International community should make their contributions while pressing Indonesia to fulfill its responsibilities.”

- Reparations are requested, “…from the Permanent members of the Security Council.” And “…governments who provided military assistance, including weapons sales and training, to the Indonesian government during the occupation and business corporations who benefited from the sale of weapons to Indonesia.”

- Duration of the reparations program, “…an initial period of 5 years, with the possibility of extension. It is recommended that the scholarship program for children continues until the last eligible child turns 18 years old, that is, in 2017.”

The CAVR report makes several recommendations for achieving justice including that:

*The United Nations should renew the mandates and funding of the Serious Crimes Unit (SCU) and Special Panels in Timor-Leste, established to try those responsible for the violations. Both bodies should be placed under the jurisdiction of the UN.

*The international community should apply the principle of universal jurisdiction to bring cases against Indonesian perpetrators, especially those previously indicted by the SCU. The international community should pressure Indonesia to achieve accountability for the abuses committed in Timor-Leste and make cooperation contingent upon progress toward this. The government of Indonesia should declassify information held by its security forces that could contribute to justice, and should educate its people and public institutions about the crimes committed in Timor-Leste.

The report, thus, calls for reparations and judicial proceedings as a foundation for reconciliation. It calls for setting up a reparations program for victims of the conflict, to be funded not only by Indonesia, but also by the foreign governments, and weapons dealers, who were complicit in the invasion.

President Gusmao opposes reparations, asking,” How can we go to the world community, one that was indifferent to our plight for too long, when it did finally help us achieve independence and made enormous contributions exceeding $1 billion to help us cope with our emergency situation? We still need their help and should not be ungrateful for what they have contributed. They are making amends for their mistakes.” This conflation of development aid and reparations does not sit well with critics who say that this allows donors to sidestep their responsibility. The CAVR report also distinguishes between development assistance and reparations, both necessary but not substitutes since reparations involve symbolic atonement.

The President believes that there is no support within the Security Council for an International Tribunal and thus East Timor needs to seek another way forward to sustain the process of reconciliation. He told me that there is nothing new or untrue about the CAVR findings, which begs the question, what could possibly be the harm of releasing a report based on public hearings that presents nothing new? As a Timorese he sympathizes with the conclusions regarding responsibility, but as a leader he argues that the national interest is not well served by remaining fixated on the suffering Timorese endured during their long struggle for independence.

In his view, “We can best honor that struggle and these sacrifices by building a better democracy here, improving governance and providing better services to the people. We also must respect the courage of the Indonesians in accepting our independence and not disrupt their progress towards democratization by demanding formal justice. The political situation remains fragile in Indonesia and there is a risk that we could help unite forces opposed to SBY’s (President Susilio Bambang Yudhoyono) reform agenda. It is absolutely in our interest to see our huge neighbor succeed in these reforms; this is our best protection.”

He also expressed concern that, “ Going down the path of prosecuting Timorese for their past actions during our struggle for independence will open old wounds, divide people at a time when we need unity and lead to chaos. This is dangerous because it could become a policy of political persecution.” He recalled his days as the leader of the armed resistance and the profound sadness he felt on losing soldiers. “ In 1981-82 every time I lost a soldier I cried like a child—I was so miserable. I wondered how can I assure myself that we can endure and prevail. I cried thinking of those who lost their lives fighting for independence. My men respected my sorrow but one day a platoon leader came to me and told me to stop crying. He said they already died. Now your duty is not to cry for everyone that dies. Take care of us that are still alive. This is a good lesson in how to look at the current situation. I understood his wisdom and believe that it is important now that we have independence to show respect for those who gave their lives by taking care of those who survived.”

Foreign Minister Jose Ramos-Horta, a Nobel laureate, rhetorically asked me, “Why didn’t the UN establish a tribunal here back in 1999 when they had 7,000 PKO here who could have arrested the culprits in West Timor? There is not much we can do to bring Indonesians to trial by ourselves. This isn’t only pragmatism. I sincerely believe that Indonesia is making progress on democratic reforms and strengthening the rule of law. However this takes a long time and the situation is fragile. SBY (President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono) is weak and does not fully control the military and can’t challenge them in this way without risking that his opponents would gang up on him. It is important that we do not destabilize the slow process of democratization in Indonesia because it is our best guarantee. They have shown the courage to accept our independence. Knowing that the situation is so difficult and that the UN Security Council doesn’t want an International Tribunal it doesn’t make sense for us to pursue it.” [4]

Left unsaid, but undoubtedly on the minds of the leadership, is the recent resumption of military cooperation between the US and Indonesia. Eduardo Gonzales, Senior Associate at the International Center for Transitional Justice (ICTJ), observed, “The geopolitical setting has changed dramatically since 9/11. Now Indonesia is a valued ally in the global war on terror. Because of that there is little inclination in the international community to press Indonesia hard on what happened in 1999. Sadly, such geopolitical considerations create double standards of justice.” [5] Gonzales strongly supports prosecution of perpetrators, arguing that the failure to do so “erodes the quality of independence and democracy in East Timor.” However, he agrees with Ramos-Horta that the UN has failed to act on several occasions when it could have promoted justice and prosecution.

The CAVR report is also inconvenient because it opens old wounds between domestic political groups that fought a civil war and engaged in violent internecine reprisals. The president conveyed to me in no uncertain terms that he is most concerned about the frank discussion concerning these internal conflicts. In his view, prosecuting those who committed such crimes carries significant potential for reviving dormant antagonisms and a descent into renewed chaos.

Clearly, the past resonates loudly in contemporary East Timor and people are finding that the truth is not setting them free. At issue is how to achieve accountability, justice and healing. The President believes that the way forward is based on getting at the truth of what happened, granting amnesty where appropriate and turning the page on this dark chapter while the Church, civil society organizations and many victims emphasize breaking the cycle of impunity and prosecuting those responsible for committing crimes.

The President defends an ongoing bilateral initiative with Indonesia called the Commission for Truth and Friendship (CTF) despite criticism that it emphasizes reaching closure, has no judicial mandate and only ensures impunity for ranking perpetrators. The Catholic Church in East Timor held a workshop on December 10, 2005 that pilloried the CTF because it was established without public consultation and offers scant prospects of truth or justice for the victims.

One organizer told me that the CTF is a doomed effort to promote collective amnesia. In the court of public opinion, the CTF lacks credibility and seems more likely to fan antagonisms than improve bilateral relations or promote reconciliation. Three commissioners from the CAVR agreed to serve on the CTF, apparently with varying degrees of reluctance and misgiving. Their concurrent tenure on both commissions has raised concerns about a conflict of interest given that they began serving on the CTF precisely when the final CAVR report was being written up. Some NGO activists have raised concerns that the final report thus may have been softened in line with the objectives of the CTF. Having seen the report and spoken with various people involved with the CAVR, including a commissioner, it is hard to conclude that any such meddling took place. It seems unlikely.

What are the prospects for the CTF? In the court of public opinion, the CTF has little credibility. It is seen as a deeply flawed process aimed at burying the past before it is fully examined and heading off recourse to justice. I was told that only the Indonesian generals who committed crimes welcome the CTF.

The President counters that Indonesia should be given another chance to come clean, doubts that amnesty will be granted and emphasizes that the CTF does not prejudice any future judicial initiatives. He takes a long-term view, arguing that progress in seeking justice and accountability for crimes committed by Germany and Japan is an ongoing process and not yet fully resolved. In his view, the time is not yet ripe for formal legal justice, but this could change depending on the international community. In the meantime, he says that it is his duty to promote reconciliation and devote scarce resources to the more pressing needs of the Timorese that are all too evident. As a leader he stresses that, “…we have to see what we can do, not what we wish to do. “

But Father Martinho Gusmao, the Director of the Justice and Peace Commission in the Catholic diocese of Bacau told me, “There is no need for reconciliation between Indonesian and Timorese people. We have no problems. The problem is that Indonesian security forces committed crimes here and they need to be held accountable. This is also part of the process of building democracy here. We need to see that nobody is above the law, and the victims in our country need to see that the victimizers -whoever they are-are prosecuted. Amnesty is meaningless and will not promote reconciliation, only resentment. Victims want their day in court.” [6]

The opposition leader Mario Carrascalao agrees and termed the government quarantine of the report “a grave mistake,” adding ”The government is worried about the impact on foreign relations. This is normal. But the report presents the voices of victims and their demand for justice and the government should respect this by releasing it.” [7]

Responding to criticism leveled by international human rights organizations, Ramos-Horta says “Its great for the human rights activists to be heroic in Geneva and New York where they don’t have to live with the consequences of their heroism. They say we don’t care about the victims? We care. The president and I have lost relatives, friends and comrades over the years. We know the cost of war, the value of peace and the necessity of reconciliation.”

Following our interview he caused a stir in publicly asserting that civil society organizations in East Timor have no moral authority to criticize the president’s efforts to promote reconciliation with Indonesia through the CTF.

In 2006 we will learn whether the CTF can deliver the truth, and whether it will lead either to justice or reconciliation.

1)Chega!: The Report of the Commission for Reception, Truth and Reconciliation in Timor-Leste (CAVR), Executive Summary. CAVR: Dili, 2005. 215 pp.

2)”Report to the Secretary-General of the Commission of Experts to Review the Prosecution of Serious Violations of Human Rights in Timor-Leste (the then East Timor) in 1999.” May 26, 2005. Members of the Commission: Justice P.N. Bhagwati ( India), Dr. Shaista Shameem ( Fiji) and Professor Yozo Yokota ( Japan).

3) Interview with President Xanana Gusmao Dec 16, 2005.

4) Interview with Foreign Minister Jose Ramos Horta Dec. 13, 2005.

5) Interview with Eduardo Gonzalez, Senior Associate, International Commission for Transitional Justice.

6) Interview with Father Martinho Gusmao, Director of Justice and Peace Commission of Bacau, December 17, 2005.

7) Interview with Mario Carrascalao, December 16, 2005.

Jeff Kingston is Director of Asian Studies, Temple University Japan. This is a revised and expanded version of an article that appeared earlier at Japan Focus. Posted at Japan Focus on January 22, 2006.