Healing Old Wounds with Manga Diplomacy. Japan’s Wartime Manga Displayed at China’s Nanjing Massacre Memorial Museum

Ishikawa Yoshimi, interviewed by Kono Michikazu

KONO MICHIKAZU This year I was in Nanjing on August 15, the anniversary of Japan’s surrender in World War II. I was with you, in fact, attending the opening of an exhibit that was the product of three years of effort on your part: “My August 15,” an exhibition by Japanese manga artists at the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall. One should probably note here that a contentious debate continues to rage between Japan and China, and among Japanese scholars as well, over the facts of the so-called Nanjing Massacre,* including the number of victims and the authenticity of certain documents. And the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall, which has “300,000 Victims” engraved in large letters near the main entrance, is regarded by many in Japan as a kind of rallying point for anti-Japanese sentiment in China. What a bold, pathbreaking idea, to choose this memorial hall, and the symbolic date of August 15, to exhibit cartoons describing the wartime suffering of the Japanese, whom the Chinese have tended to view solely as aggressors!

I’d like to hear something about the origins and history of the exhibition. I understand that in August 2000 you led the Japan-China Manga Friendship Tour, which brought a group of fifteen manga artists to China—cartoonists like Chiba Tetsuya, Matsumoto Reiji, and Morita Kenji. Was that how it all began?

Touring China With A Busload Of Clowns

ISHIKAWA YOSHIMI Yes, that’s right. I happened to have gotten acquainted with several of the chief officers of the publisher of Renmin Ribao [People’s Daily] over the years, and I was aware that for thirty years that organization had also put out a weekly cartoon newspaper called Fengci yu Youmo [Satire and Humor], one of the only publications of its type in the world. I found it fascinating that the organization responsible for the official news organ of the Communist Party of China put out a paper like this as well. And I found myself wondering if it would be possible to create some opportunity for Japanese manga artists to visit China and rub shoulders with Chinese cartoonists, and perhaps even compile and publish a book together. That plan came to fruition in August 2000. My contacts at the People’s Daily put me in touch with a company that published the book, and the reception surpassed all expectations. There’s been considerable cultural exchange between Chinese and Japanese economists, writers, musicians, and so forth, but this was the first attempt to bring Chinese and Japanese cartoonists together.

|

The opening of the manga exhibit in Nanjing on August 15, 2009, the anniversary of Japan’s surrender |

KŌNO Who was your point man among the manga artists?

ISHIKAWA Morita Kenji. As a child, Morita lived through the traumatic evacuation and repatriation of Japanese settlers in Manchuria following World War II, as did Chiba Tetsuya and the late Akatsuka Fujio. He’s also a very well liked and respected figure and a director of the Japan Cartoonists Association. Cartoonists tend to be mavericks; it would have been impossible to get them organized without the help of someone like Morita. He persuaded others to take part so that the project could move forward.

KŌNO I’ve heard you say that for a trip to China, there are no more entertaining travel companions than cartoonists. In what way were they entertaining?

ISHIKAWA Well, in the first place these are people who make a living by thinking up nutty jokes and antics. Their behavior is no different from their comics. To put it another way, there’s nobody less suited than they are to going about as a group. They’re undisciplined. They’re slobs. You can’t do a thing with them. Turn your back on one of them for an instant, and before you know it he’s approached some woman and is drawing a caricature of her while a whole crowd of children gathers around. That sort of thing happens constantly, wherever you go, so as tour guide, I’m on pins and needles the whole time. Once we were supposed to meet with some VIPs, but one of the group hadn’t shown up. Suddenly we heard a commotion. I ran out to see what was going on, and there he was, dressed sloppily, arguing with the doorman. He’d been stopped at the entrance because they couldn’t believe someone who looked like that was on his way to meet with VIPs. You have grown men clowning the whole time and quoting that line from Akatsuka Fujio’s manga—”Everything’s okay!” You couldn’t find a more entertaining group.

KŌNO I heard that on the first trip one of them was dressed up as a samurai the whole time.

ISHIKAWA That’s right. And someone always goes missing. It happened this time in Nanjing, too—I won’t say who. We tell everyone to please get on this boat, but someone decides he wants to get on that one instead. They don’t care what anyone says. I guess if they weren’t that way, they wouldn’t be able to draw such funny cartoons.

Getting Past The Censors

KŌNO How popular were Japanese manga in China at the time of the 2000 tour?

ISHIKAWA Oh, they were tremendously popular. When the government began to allow television stations to air Japanese programs, anime series like Tetsuwan Atomu [Astro Boy] and Ikkyū-san became an overnight sensation. All the children we met knew about them. Soon pirate editions of manga like Doraemon and Meitantei Konan [Detective Conan] were pouring onto the market, triggering a huge manga boom.

KŌNO And it seems you were quick to recognize the potential of manga. In the autumn of 2000, you stated that the time was approaching when manga would be Japan’s most potent medium of international exchange.

ISHIKAWA Over the past ten years I’ve been involved in a variety of activities to promote exchange between Japan and China, sitting on the planning committee for programs commemorating the thirtieth and thirty-fifth anniversaries of the normalization of diplomatic relations, for example. I’ve discussed bilateral relations with China’s political leaders, scholars, and others. And I’ve concluded that in the final analysis, the problems that continue to divide Japan and China all boil down to people’s perception of the events of the 1930s and 1940s. The Chinese people remain very bitter about the war that raged on Chinese soil for fifteen years, beginning with the Manchurian Incident of 1931. Their feelings about this go far, far deeper than most Japanese people imagine. Unless we can overcome that somehow, there’s always going to be bad blood between our two nations. On the other hand, the Chinese are almost completely unaware of the suffering endured by the Japanese people during World War II. That’s because they’ve been taught since childhood that the Chinese people were the victims, that they stood up to the Japanese aggressors, resisted them valiantly, and ultimately prevailed. They’ve never given any thought to what sort of experience World War II was for the Japanese people.

I came to the conclusion that unless we could bridge this vast perception gap, the problem would simmer indefinitely, flaring up again each time someone in Japan said something that rubbed the Chinese the wrong way. I wondered if there wasn’t some way at least to get the Chinese and Japanese people looking at things from a shared perspective. I began to think about what one could do to make the Chinese aware that the Japanese had their own painful memories of the war.

|

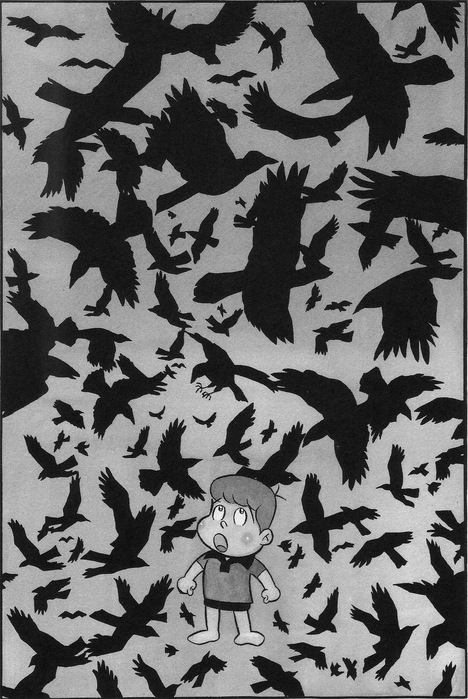

The Red sky and crows © Akatsuka Fujio |

Just around that time, Morita had brought together a group of cartoonists, primarily people who had been involved in the evacuation from Manchuria, for his “My August 15” project. In 2003 he had the artists submit cartoons and short essays describing where they were and what they were doing on the day Japan surrendered. They held an exhibition of those works in the form of illustrated letters, and the following year they published a book.*

When I saw the book, it was like a bolt of lightning. I felt intuitively that we could make use of it to communicate the Japanese experience to the Chinese people. First of all, I wanted to translate it and get it published in China. Everyone in the Japanese Foreign Ministry and every China expert I talked to said it couldn’t be done, but I figured nothing ventured, nothing gained. I inquired at four top publishing companies in China, but they all turned me down. “The Party will never allow it,” they said. “Even if we published it, no one would buy it.” Of course, I had never thought of it as something with real market potential. I just thought if we could only get a Chinese edition out in book form, somebody was bound to read it, and that could set something in motion.

Finally I decided to take it to the People’s Daily. Xu Pengfei, the editor in chief of Satire and Humor, is a friend of mine, so I decided to ask him what he thought. He was enthusiastic about the cartoons, but he thought the text would probably run into trouble with the Party censors. So, I got the best translator I could find, had all the problematic parts translated with great care, and took the text to the top brass at the People’s Daily. They knew me already, so they read it carefully, but their reaction was, “This is going to be a problem.” I asked, “Which parts?” And they showed me in great detail everything that was wrong. I think they figured we’d give up at that point. But instead we reworded all those passages without changing the basic meaning, and I took it to them again. We repeated this process several times. The artists had agreed to leave all the negotiations to me on the understanding that I wouldn’t compromise their work. It was looking like we were close to clearing the final hurdle when the publisher told me to bring in the cartoons. For the first time, I gave them the manuscript complete with the pictures.

Three months passed with no word. I was beginning to think that it wasn’t going to happen after all, when I received a communication asking that I come to Beijing. I figured I had no choice, so I went again, and this is basically what they told me: “We agree that these are highly artistic works that aptly convey the feelings of the Japanese people. But there’s a danger that these pictures will inadvertently awaken memories among the Chinese people and stir up trouble. We’re concerned that the reaction could snowball far beyond anything the artists intended. That would destroy the purpose of your project. So, we were wondering if you would mind cutting these five pictures.” Finally we’re getting somewhere, I thought.

Well, to make a long story short, in the end two of the five pictures were cut, two were slightly revised by the artists, and one made it into the publication just as it was. I knew from the beginning that we were involved in something akin to diplomatic negotiations and that we weren’t going to get everything we wanted. The censors had to save face, after all. So, I was prepared to give way wherever it was possible to compromise. But there was one cartoon that I fought hard to preserve intact. In the end we were able to resolve the impasse thanks to Xu Pengfei, who is also chairman of the China Artists Association Cartoon Committee, which promotes exchange between Chinese and Japanese cartoonists. He said, “The artist who drew this is a friend of mine, and I’m going to make sure that it stays in no matter what.”

Last year, after many months of this, we achieved our objective with the publication of the Chinese edition by the People’s Daily. This was huge. After all, the People’s Daily is directly under the CPC Central Committee’s Publicity Department, so the fact that they published it means that it cleared China’s toughest censors. Everyone was amazed to hear that the People’s Daily was publishing it. The whole process had taken about a year and a half. The book was distributed to school libraries and all kinds of institutions in China, and it elicited some amazing reactions. Children who had never heard about the US firebombing of Japanese cities shed tears before my very eyes, saying they had never seen such sad cartoons.

|

Bucket relay fire drill © Kitami Ken’ichi |

A Risky Undertaking

Meanwhile, though, I was beginning to feel that it would be a shame to stop at publishing a book. I was wondering if it would be possible to exhibit the original artwork. People around me said, “Just be satisfied that you got the book published!” And when they heard that I wanted to hold the exhibition at the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall, they dismissed the possibility out of hand. But I was betting it could happen. I had no rational reason for hope, yet I felt oddly confident.

An opportunity presented itself by chance last November, after I was back in Japan. I happened to be looking over a list of people visiting Japan from China, and I noticed that the group included Zhu Chengshan, chief curator of the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall. With the help of an acquaintance of mine in the Chinese embassy, I was able to set up an appointment. I went by myself, met him for the first time, and explained what I had in mind. I won’t reveal the details of our conversation, but suffice it to say that Zhu expressed his openness to the idea on the spot. “I don’t see why not,” he said. “I’ll give it serious consideration.”

Immediately after the winter holiday, I traveled to Nanjing and started lobbying hard to let them know I was serious. Zhu responded very positively, saying, “By all means, let’s do it.” He said there would probably be some backlash in China, but reading the book, he had been impressed by the illustrations and the way the letters conveyed the feelings of the Japanese people at the time of Japan’s surrender. He said, “This memorial hall wasn’t built to fan anti-Japanese sentiment. Its purpose is to help ensure that our memories of the war don’t fade, not to condemn the Japanese people.” He said he was determined to be the first to mount an exhibition in China describing the wartime experiences of the Japanese.

I had some idea of the dangers involved in holding such an exhibition in China, and I was moved by Zhu’s courage. It was a risky undertaking that could have ended in disaster if things went wrong. But Zhu said, “It’s worth doing here precisely because it’s risky.” I was deeply affected by that. Zhu is a really decent and courageous individual. So many people in Japan had told me that he was as anti-Japanese as they come, and I had to wonder if they were talking about the same person.

KŌNO Was it your idea to have the opening on August 15?

ISHIKAWA No. I said that it would take about five months to finish all the preparations, so the exhibition could probably open in June. Zhu said, “Since the title specifically mentions August 15 as an important day to the Japanese people, why not have the opening on August 15?” Nanjing would be at its hottest, but Zhu felt that it was the job of the memorial hall to convey what August 15 meant to the Japanese people, and he wanted to be true to that concept. He also said that his plan was to keep the exhibition open there for three months and then, if possible, have it travel to the Marco Polo Bridge Memorial Hall. After that, he wanted to install it as a permanent exhibit at the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall.

I went back to Japan all fired up, and two months later I returned to Nanjing by myself with 162 pictures for exhibition. We had talked about ways of attracting more visitors, such as a side exhibit of forty original drawings by famous manga artists and a display of bound Japanese manga, and we followed through on that. My feeling was that we needed to make the exhibit welcoming, accessible, and attractive to kids.

KŌNO Still, I imagine you had reason to worry right up until the opening.

ISHIKAWA You bet I did. This was the equivalent of exhibiting pictures of the wartime experiences of the Chinese at Yasukuni Shrine. That’s how risky it was. And with all the activity on the Internet now, there was no telling what kind of flame wars might break out online. I did my best to appear unconcerned, but inside I was very uneasy. In China you can never be sure that a particular controversy won’t ignite a wildfire of protest. I know for a fact that there were a lot of high-level discussions within the Chinese government before the exhibition opened, and the greatest precautions were taken on the day of the opening.

Fortunately, when I contacted the Memorial Hall a few days after the opening, I was told that there had been only two complaints lodged, and apart from that the reaction was largely favorable. Of course, there were people who commented that the Japanese had started the war, after all, so they were just reaping what they had sowed. But I was hoping people would express a variety of opinions, that the pictures and text would give rise to discussion, because I think it’s important that we enter into a constructive dialogue concerning World War II. Soon after the opening, museums in places like Harbin and Tianjin were expressing an interest in hosting the exhibition. I want it to receive as wide exposure as possible because, after all, it’s a country of 1.3 billion people.

Finding Common Ground

KŌNO I also met Zhu Chengshan, and the first thing that struck me about him was his youth. He’s in his late fifties, and that’s surprisingly young considering that he’s held the post of chief curator for eighteen years of the memorial’s twenty-four-year existence. Also, I had assumed he was of the prewar generation because I had heard he was an extreme hard-liner in terms of his historical perspective on Japan. In any case, Zhu said he had never met a Japanese like you before.

ISHIKAWA He told me that he had visited Japan about forty times and had met with any number of Japanese politicians, scholars, and others, yet he had the feeling he had only met two basic types. On the one hand were the apologetic ones, who were constantly expressing their guilt over the brutal behavior of the Japanese in China. And on the other hand were those who focused solely on the casualty count of the Nanjing Massacre, taking issue with the Chinese position that the victims numbered three hundred thousand—or in some cases saying that the name of the memorial should be changed or a certain photograph removed from the exhibits. But according to Zhu, I didn’t fall into either of those categories.

KŌNO Yet I understand that you suggested some changes in the memorial.

ISHIKAWA What I pointed out was that people from countries all over the world—regardless of their role in World War II—visit the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum to pay their respects to the victims of the atomic bomb. But it’s still very difficult for Japanese tourists to visit the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall, notwithstanding all the efforts of those responsible for it, and I don’t think that’s because the Japanese are cowards. It’s because the entire memorial is devoted to the atrocities perpetrated by the Japanese. The memorial may have been established to prevent people from forgetting about the war, but I think it has veered in a slightly different direction.

That’s what I said. Then I showed him the book of pictures by Japanese cartoonists and proposed an exhibition. It would attract Japanese visitors to the memorial, and the Chinese would learn something about the Japanese people. I suggested that this kind of sharing of war memories was consistent with the fundamental purpose of the memorial, which was originally intended as a memorial to war and peace, not a monument to hatred of the Japanese. And Zhu agreed.

KŌNO The memorial gets a huge number of visitors, as many as six million a year. I understand that ethnic Chinese in other countries usually make it part of their itinerary when they visit Nanjing, China’s old capital. Since the exhibition coincided with summer vacation, I saw a lot of Chinese families, too, but I was also surprised by the number of visitors speaking English. They said twenty thousand visitors were admitted to the exhibition on the opening day.

ISHIKAWA Before the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, large numbers of Chinese, particularly those loyal to the defeated Kuomintang [Nationalist Party], fled from the mainland to Taiwan, and many emigrated from there to North America and elsewhere. For two or three generations these émigrés have passed down the story of the horrors that occurred when the Japanese army overran China’s beautiful ancient capital. These overseas Chinese communities have produced people like Iris Chang, author of The Rape of Nanking [1997]. The first place many of these second- and third-generation ethnic Chinese want to go when they visit China is Nanjing. They visit the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall and go home deeply shocked. The hall has undergone two major expansions, resulting in the large modern structure you see now, with a site area of seventy-four thousand square meters, and most of the funding for that was donated by overseas Chinese. From the beginning the memorial was built with contributions from ordinary people, not government funding, but we need to understand that today it’s these passionate overseas supporters who are sustaining the memorial. These are the same people whose vigorous lobbying pushed the US Congress to pass a resolution that severely condemned Japan for the Imperial Army’s use of “comfort women” in the 1930s and 1940s. That’s why it’s so very important for these second- and third-generation overseas Chinese to see and respond to works by the creators of Doraemon and Anpanman.

Leveraging Our Cultural Assets

KŌNO The Japanese were among the first to emphasize the concept of “soft power,” and for a while we were feeling pretty good about our cultural impact, what with the overseas media praising Japan’s “gross national cool” and so forth. But the government never pursued the idea wholeheartedly. It seems to me that South Korea and China have thought more seriously about the possibilities and taken concrete measures to realize them. For example, General Secretary Hu Jintao’s report to the Seventeenth National Congress of the CPC talked about the need to “enhance culture as part of the soft power of our country.”

ISHIKAWA Japan doesn’t understand how to capitalize on its cultural assets. You might say we lack capable producers. Former Prime Minister Asō Tarō talked about the power of manga, and in a way he was right. But we don’t have a clue how to use it. I think that’s because we don’t really understand what’s so special about Japanese manga.

Of all the people in the world, children are the most exacting and truthful critics. And Japanese manga have totally captivated these most exacting of critics. These are people who judge purely on the basis of what they like, regardless of nationality or race or language. Conversely, once children decide they don’t like something, nothing their parents say or do will make them like it. But one thing that entrances children all over the world is Japanese manga. I was sure the CPC would realize this. And adults can’t say no to the things their children love. I was confident on that score.

Every time we do a demonstration of manga in China, we get the same question: Why are Japanese manga so popular? I answer this way. Where do Japanese cartoonists start when they draw a face? Generally speaking, they start with the eyes. There’s no hard and fast rule, but that’s how most of them go about it. That’s because the eyes are the crucial element. The eyes of Japanese cartoon characters appeal to children the world over. Children judge people almost solely by their eyes—whether they’re friendly eyes, angry eyes, or what. Think about whose eyes are the most appealing from a child’s viewpoint. The eyes that Japanese cartoonists draw are so kind and gentle—huge, sweet eyes without a hint of malice. Children the world over are enchanted by those eyes.

What we need is producers with ideas about how and where to leverage the power of Japanese manga. And the same is true for Japanese cuisine and every other aspect of Japanese culture. Japan has plenty of great material, but we’re lacking in people with the ability to translate all that into soft power. That’s our biggest obstacle.

KŌNO Well, it’s clear to me you’ve breached that barrier with the soft-power triumph of “My August 15,” and I feel lucky to have caught a glimpse of that triumph. Unfortunately, we had to catch a plane back to Japan the morning after the opening, but I was touched that Zhu Chengshan got up early on his day off to see us off at the airport.

I hope your exhibition will go on to even greater success.

Ishikawa Yoshimi, interviewed by Konō Michikazu, “Healing Old Wounds with Manga Diplomacy,” was published in_Japan Echo_, Vol. 36 No. 6, pp. 52-56. Reproduced by permission of the publisher.

Translated from an original interview in Japanese. Interviewer Kōno Michikazu is former editor in chief of Chūō Kōron. The Japanese original, published by JB Press, is available here.

The critic and non-fiction author Ishikawa Yoshimi (1947-) is therecipient of the 1989 Ōya Sōichi non-fiction prize for Sutoroberi rōdo (Strawberry Road, 1988). President of Akita Prefectural Junior College of Arts and Industrial Arts between 2001 and 2007, he serves on the Shin Chūnichi Yūkō 21-seiki Iinkai (Committee on China-Japan Friendship in the 21st Century). He is the author of, among others, Igi ari: ugokanu Nihon wo ugokasu tame ni (Objection! In Order to Move Japan that Does Not Move, 1998) and Rokujū-nendai-tte nani? (What’s the Sixties?, 2006).

Manga illustrations included here are from Boku no Manshū: mangaka-tachi no haisen taiken. Chūoku Hikiage Mangaka no Kai (ed.) Aki Shobō, (1995) 2005.

*The Nanjing Massacre (also called the “Rape of Nanking”) refers to the outbreak of atrocities by Japanese soldiers against Chinese citizens in Nanjing (Nanking) in the months after the city was taken by Japanese forces near the end of 1937.—Ed.

*The book, Watashi no 8 gatsu 15 nichi (My August 15), is available for purchase here. (site in Japanese only).

Recommended citation: Ishikawa Yoshimi, “Healing Old Wounds with Manga Diplomacy. Japan’s Wartime Manga Displayed at China’s Nanjing Massacre Memorial Museum,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 10-1-10, March 8, 2010.