Japan Stares into a Demographic Abyss

By Hisane MASAKI

TOKYO – Japan’s population is shrinking and graying, at a rate probably unprecedented in history, and there is no sign the trend will stop soon: the nation’s birth-rate figures for 2005, due to be released shortly, are expected to hit a new record low. Not only is Japan’s birth rate already among the lowest in the industrialized world, but its pace of decline is the fastest, raising grave concerns about a possible erosion of the economy’s international competitiveness as the population thins out.

In response, a number of Japanese firms have started to improve their child- and elderly-parent-care programs, driven not only by concerns about a possible labor shortage after the baby-boomer generation starts retiring next year but also by growing awareness of the need to secure qualified workers, especially women, over the long term amid the dwindling working population. Some electrical appliance manufacturers have even introduced programs granting their employees leave to receive fertility treatment.

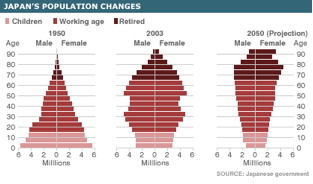

Japan is at a historic juncture demographically, with the rapid aging of the population and precipitously declining birth rates. Japan’s population began to decline for the first time since World War II last year, two years earlier than expected. The working-age population had already begun to shrink several years earlier. Japan’s total fertility rate – the number of babies born to every woman during their reproductive years – stood at 1.29 in 2003 and 2004. If the current low birth levels continue, in the absence of changing immigration patterns, Japan’s population, now 127.7 million, is forecast to shrink to half of its present size in 70 years, and to a third in 100 years. The percentage of people aged 65 or over has reached 20% of the total population, while that of children aged 14 or under has declined to 14% – a phenomenon eerily apparent on the streets of Japanese cities, where the laughter of children has become increasingly rare.

The Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare will release this month or next the 2005 total fertility rate, which is widely believed to have hit a new record low of around 1.26 or possibly even lower. A minimum rate of 2.07 is reportedly needed if Japan is to avoid a population decline, but the actual rate has been lower ever since logging 2.14 in 1973. The rate dropped to about 1.5 in the early 1990s and below 1.3 in 2003.

Japan’s birth rate has actually declined faster than earlier government predictions. A median forecast released by National Institute of Population and Social Security Research in 2002 called for the nation’s total fertility rate to stop declining after dipping to 1.306 in 2007 and to stabilize at 1.387 from around 2035. According to the Cabinet Office, in 2003 the total fertility rate was 2.04 for the United States, 1.89 for France, 1.34 for Germany and 1.29 for Italy.

The Japan Aging Research Center in Tokyo predicts that the nation’s total fertility rate will plummet to 1.16 in 2020 from 1.29 in 2004, leading the center to predict in a recent report that the population will shrink by about 30% to 88.3 million in 2050.

Inertia and ineptitude

Another record low birth rate, if confirmed, will highlight once again that a series of measures taken – and highly publicized – by the Japanese government in the past decade or so to reverse the declining trend have been a complete failure. Among those measures are the Angel Plan, introduced in 1994, and the New Angel Plan, introduced in 1999. Under those plans, wide-ranging programs were implemented to encourage people to have children.

Critics point out that government measures taken to date have been almost useless. They even claim that the government has not been serious enough about the problem, citing the fact that 70% of the social-welfare budget goes to programs for the aged, such as pensions and medical services, with only 4% set aside for services for children, such as child benefits and child-care services. The government’s education-related spending is also the lowest among industrialized countries in terms of its ratio to gross domestic product (GDP).

Japanese have become increasingly concerned about the future as social-security costs, such as pension contributions and insurance premiums for medical care and nursing care for the elderly, as well as tax burdens, are expected to keep rising sharply amid declining birth rates and the rapid graying of society. While having to pay more pension premiums today, current Japanese workers face the prospect of reduced pension benefits after retirement as the ratio of employees to retirees plummets.

In addition, more and more Japanese are living alone. Even as Japan’s population began to contract last year, the number of households rose in all 47 of the nation’s prefectures and hit a record high of 49.52 million, reflecting an increase in the number of elderly citizens and youths who live alone.

A major reason for the falling birth rate is the growing trend to marry late or not at all. The average age at first marriage in 2004 was 29.6 years for husbands and 27.8 for wives. The average age when a woman gives birth to her first child was 28.9 years in 2004, versus 27.5 in 1995. Marriages decreased for the third straight year to 720,429, or 19,762 fewer than in the previous year. And marriages per 1,000 people were 5.7, the lowest on record.

The proportion of elderly in

Japan is rapidly increasing

Economic factors are most often cited as the primary reason more and more Japanese get married in later life or choose – or are even forced to choose – to remain single. Working women find it particularly difficult to combine employment and child-rearing because of the poor quality of child-care services available, unfavorable employment practices, and rigid working conditions.

According to a recent Cabinet Office survey, only about 40% of Japanese parents said they wanted to have more children, the lowest percentage among the five countries surveyed (the others were Sweden, the US, France and South Korea). Of the Japanese polled who did not want to have more children, 56% cited financial reasons for their reluctance. Meanwhile, 81.1% of Swedes polled said they wanted to have more children, with the comparable number reaching 81% in the US and 69.3% in France.

“In those three countries, there are good child-support services and tax benefits,” a Cabinet Office official said. “I think that’s the reason for the [high] birth rates.”

In South Korea, 43.7% said they wanted to have more children.

Acceptance of foreign labor

The rapid demographic changes have alarmed Japanese policymakers. In addition to a further shrinkage in the working population, the continuous decline and rapid graying of the population are matters of deep concern because they will ultimately mean lower consumer spending as well as a drop in the savings rate. All of this poses a serious potential threat to the competitiveness of the world’s second-largest economy.

Meanwhile, pressure is also growing, especially from domestic industries, to accept more foreign workers to alleviate an anticipated serious labor shortage.

Late last month, the Council on Fiscal and Economic Policy, headed by Prime Minister Koizumi Junichiro, released an interim report on the government’s global strategy to reinvigorate the economy, which calls for the acceptance of foreign workers in fields that are not currently open to them, to help maintain high economic growth in light of the low birth rate and the graying of society. The global strategy, to be finalized this month, will be incorporated into the annual basic policy on economic and fiscal management and structural reform to be compiled in June.

The interim report calls on the government to review the types of jobs open to foreign nationals and allow greater flexibility in hiring foreigners in service fields, such as the nursing-care industry where demand for workers has increased because of the graying of society. The report also calls on the government to seek to attract more foreign workers. In mid-May, the council will draw up guidelines for increasing the number of foreigners employed in Japan.

The council’s call to allow more foreigners to work in Japan highlights its deepening concerns over the possibility of maintaining high economic growth if more foreigners not permitted to obtain jobs here. According to estimates by the Health, Labor and Welfare Ministry, by 2030 the number of workers will drop by about 10 million from its current level to about 56 million. The Cabinet Office also forecasts that one in every 20 people will have to be employed in the nursing industry in 2030 to provide the current level of care.

But many Japanese remain concerned about a possible influx of foreign workers. They fear, among other things, that public security would deteriorate, as the number of crimes committed by foreigners has been rising sharply in Japan. Echoing such concerns, Health, Labor and Welfare Minister Kawasaki Jiro cautioned recently against allowing more foreign workers. Kawasaki said the government should expand employment opportunities for senior citizens, women and young men for the time being.

Kawasaki also noted that a rise in foreign workers would reduce employment opportunities and lower salary levels for Japanese. Experts state that if the government decides to allow greater numbers of foreigners into the country, it must first act to prevent public discord or disorder that could result from cultural differences. The council’s interim report says the government will map out general guidelines this year for solving problems foreign workers might face in areas such as health and education, as well as measures to prevent friction between Japanese and foreigners.

On April 30, one piece of bright news came from the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare, which said Japan’s labor force – those currently employed or seeking jobs – rose to 66.54 million in fiscal 2005, up 150,000 from fiscal 2004 and marking the first increase in eight years. The gain came as the ongoing economic recovery encouraged women and retirees to re-enter the job market.

After falling to a recent low in fiscal 2002, 220,000 women joined the labor force over the following three years, bringing the total number of female workers to 27.52 million in fiscal 2005. Meanwhile, the number of those aged 60 or older who are either employed or looking for jobs reached 9.67 million in fiscal 2005, up 450,000 from five years earlier. The country’s labor force is expected to remain under downward pressure, however, as the population of workers between 15 and 64 will likely further decline.

Competition for domestic labor

Meanwhile, many major Japanese companies have recently begun to compete for a better work environment to secure qualified workers, especially female ones, amid the shrinking working population.

For example, Matsushita Electric Industrial Co has extended the period during which both male and female employees can take child-care leave. Employees are allowed to take leave twice, for up to two years in total, to care for preschool children. Some other companies have extended paid child-care leave or are allowing employees to work fewer hours. Toshiba allows workers to take paid leave for child care by the hour. This allows parents to take their children to and from kindergarten or attend to sick children.

Mitsubishi Electric and Ishikawajima-Harima Heavy Industries used to let their employees work reduced hours only to care for preschoolers. But both firms have changed their programs to allow them to do so until their children become third-graders. Sharp has promised to rehire any female employees who quit after childbirth to care for a child, any time up until the child enters primary school. Some electrical-appliance manufacturers, including Matsushita and Toshiba, have even introduced programs under which employees are granted leave to receive fertility treatment. Matsushita’s “child plan leave system” allows such leave to be taken for up to one year.

In addition, Toyota Motor opened its third nursery for employees in its home base of Aichi prefecture. Nissan Motor Co has set up what it calls “maternity protection leave”, which allows female workers in factories or other manufacturing facilities to take leave as soon as they learn of their pregnancy. Kawasaki Heavy Industries Ltd introduced a system under which employees’ leave period for child-rearing or nursing care can be counted in the years of continuous services they have given to the company, based on which retirement allowance is calculated.

Hisane Masaki is a Tokyo-based journalist, commentator and scholar on international politics and economics. His e-mail address is [email protected].

This is a slightly revised version of an article that appeared at Asia Times on May 8, 2006. Posted on Japan Focus May 14, 2006.