Translated by Hiroaki Sato

Translator’s note:

What follows is a translation of the second half of Ōe Kenzaburō’s article, “America ryokōsha no yume—jigoku ni yuku Huckleberry Finn,” which was first published in the September 1966 issue of the monthly Sekai (The World). The untranslated first half begins, “America. I shall never become entirely free from the oppressing, demonic power of the word America,” and describes how the writer has lived since boyhood “within the conflicting, extremely complicated [inferiority] complex that the word America evokes.”

Ōe first read Huckleberry Finn as a boy in a remote Japanese mountain village. The United States and Japan were at war at the time, and his mother told him that if his teacher caught him with the book, he should tell her that “Mark Twain” was the pseudonym of a German author. As Ōe recalled in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech, “The whole world was then engulfed by waves of horror. By reading Huckleberry Finn I felt I was able to justify my act of going into the mountain forest at night and sleeping among the trees with a sense of security which I could never find indoors.” Twain’s novel would make its presence felt throughout Ōe’s own books—which often center on marginal people and outcasts, on existential heroes sickened by civilization who choose to “light out for the territory”—including his new novel, Death by Water.

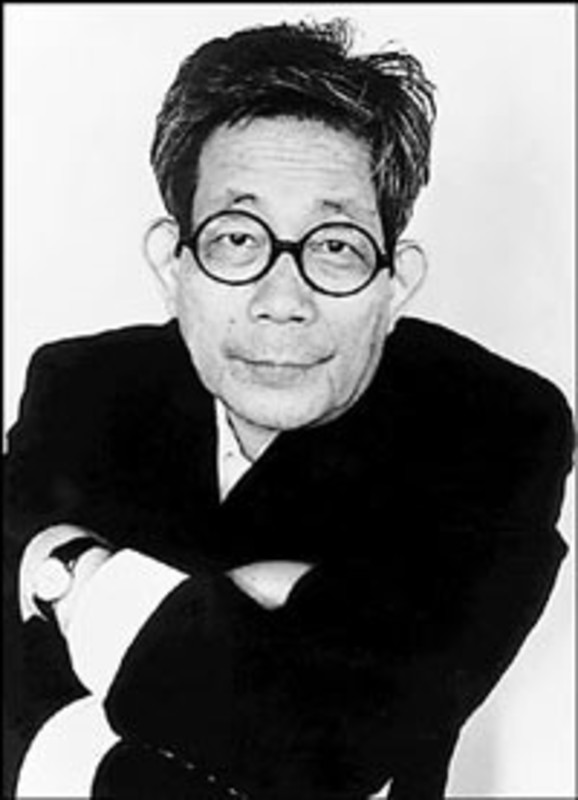

Ōe, who won Japan’s prestigious Akutagawa Prize when a 23-year-old student, in 1958, becoming the youngest writer to do so, was a French literature major at the University of Tokyo. He attended an international summer seminar at Harvard University in 1965 at a time when he was preoccupied with issues of the Vietnam War, the atomic bomb, and race relations, subjects that he would explore in his writing and speeches over subsequent decades. Ōe won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1994.

Hiroaki Sato

The summer of 1965, one morning, about the hour when the already sharp sunshine was further heating the air that was dry and not hard to bear, I was in America—Cambridge, Massachusetts—facing the subway entrance at Harvard Square, the plaza in front of the university, and the newsstand surrounding it selling foreign magazines and newspapers, not to mention America’s domestic magazines and newspapers, waiting for the moment for the traffic signals to change so I might cross. I was holding on my chest a large paper bag with salami sandwiches and bread that I was going to take to the sea that afternoon and eat with friends, orange juice, also a bottle of bourbon. In my trouser pocket I had a small edition of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn that felt bulky on my thigh through lightweight summer trousers. Sweat, heat. But with that inciting mood of a summer morning that invigorates human beings, and also, with a sense of exhaustion, I was enjoying the morning as I chatted with a French woman writer who was already beginning not to be young, who was standing by me also staring at the traffic signals.

Like me, she was a member of Harvard University’s international summer seminar, and in accordance with the unwritten rule of the seminar, I was speaking with her in English. I should have been able to talk with this French writer in French, too, but the fact that we were, quite naturally, speaking in English seems important for recreating my mood of that morning. I had arrived in America some fifty days earlier. That evening, as I joined the crowd in the plaza, I experienced a tumultuous feeling about the racial diversity of the people around me. And I felt excluded from that tumult. For all that, just about fifty days later, I, like my French comrade, was using the same language as those around me without any particular sense of strangeness. Furthermore, we two outsiders were exchanging views critical of the political trends of that country, in the language of that country. The atmosphere that enabled us to do so naturally deeply pervaded that university town.

I had just spoken of American bombing of North Vietnam, noting that Gen. LeMay was a leading force in pushing the hard-line policy in the Joint Chiefs of Staff, that LeMay had developed the plan for dropping the atomic bombs in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and that he had received the First Order of Merit with the Grand Cordon of the Rising Sun from the Japanese government for his contribution to the expansion of the Japanese Self-Defense Forces.1 Several months later I read America’s radical independent journalist, I.F. Stone, touching on the heart of the matter and quoting LeMay in a recent AP interview to the effect that ‘We can accomplish our mission better by the use of the Air Force than by the use of the ground forces.’ By ‘our mission,’ he meant: North Vietnam, you better surrender; otherwise, we’ll burn your country up. In his recently published autobiography,2 he pointed out that, when the Korean War erupted, ‘what I proposed at once was to attack the North and incinerate all the major cities just as the U.S. did to Japan during the Second World War.’ ‘I believed that that would end the war extremely fast, with minimal damage.’ That was also LeMay’s prescription for winning in Vietnam.

LeMay reveals that for three years—that is, since 1962—he had been urging the Joint Chiefs of Staff that the way to end the war in Vietnam was to let them know that ‘we’re going to bomb them back into the Stone Age.’ ‘We’ll push them back to the Stone Age not with our ground forces but with the naval and air forces.’ This is one of his favorite phrases; in World War II he boasted that the Japanese air raids ‘were driving them back to the Stone Age.’ The Stone Age is a metaphor for the days when brute force reigned supreme; instinctively LeMay harks back to it.”

Gen. LeMay’s obsession with the Stone Age is a direct result of his experience of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the steadily ballooning stockpile of nuclear weapons. Our government had decorated such a man. Of Hiroshima’s protests, a government official said, “My house was burnt down during an air raid, too, but that was twenty years ago. To go beyond love and hate to award a medal to a soldier who bombed numerous Japanese cities during the war, that’s fitting for the people of a great nation, easygoing and good, isn’t it?” I once wrote of this, calling it a betrayal of human beings in Hiroshima. Yet I, too, did not realize that these words and the decoration would encourage Gen. LeMay to have greater confidence in bombing North Vietnam. When we think that LeMay, in planning to napalm North Vietnam, rather than bearing in mind the images of Hiroshima’s ghastly corpses and those who are still alive and suffering, had nothing but the memories of the First Order of Merit with the Grand Cordon of the Rising Sun and the easygoing people of the victim nation, should not we Japanese have a terrible image before our eyes?

When I talked about Gen. LeMay’s roles of today and yesterday, the French woman writer told me that several days ago, on the 20th anniversary of the dropping of an atomic bomb on Hiroshima, a disk jockey at a local Massachusetts station who sang, “Happy Birthday, Hiroshima Day! Happy Birthday, Hiroshima Day!” was fired on the spot.

I asked her, “Did you hear the broadcast yourself or did you read a report on it in a newspaper?” Just then, four American youths riding in a Volkswagen with its top down (resembling a deep boot that can carry human beings) raced by just inches from us, shouting words of derision at us. The words I was able to understand were something like, “Hey, did you learn your lesson?” and a phrase that I had thought had become extinct, “yellow peril.” Also my woman friend was ridiculed, though of course it was not the fact, for having sexual relations with the yellow race.

And so I suddenly remembered that it was the morning of August 15 (the date of Japan’s surrender) and, realizing that I had been utterly unconscious of it till then, I felt deeply disturbed on both counts. Then, the bundle of elastic threads of mutually contradictory remembrances and emotions concerning America, and the enormous sense of humiliation, sense of liberation, and sense of freedom on that day twenty years earlier and since, overwhelmingly filled me with almost blinding force. At the same time, caught between the expression of the woman friend who, standing next to me as she was, pretended not to have noticed the ridicule from the Volkswagen and the voice of nakedly sexual derision, I felt my face turning red. The phrase “yellow peril” reminded me of the picture of a bespectacled buck-toothed ugly midget figure that was an exact caricature of the “Jap” that cheerful American female college students had shown to a group of Japanese students in my high school days. I was looking at myself through the eyes of that American comic artist. I, who until that moment, was feeling comfortable in the Harvard Square crowd, suddenly found myself alone, a bespectacled buck-toothed midget, an ugly Japanese in a comic strip. And, with no evidence whatsoever, I felt as if this comical caricature of me was trying to seduce the white woman standing next to me, and was most upset, involved as I was with sexual feeling. I felt deeply isolated and helpless, in a sort of terror. I felt like running into the entrance of the dark bar just behind us and hiding among the alcoholics who inhabit it from morning on. But the signal had changed to the blue light shaped like a walking human being and the French woman writer, having taken one step into the street, was looking back at me in puzzlement. It was obvious that I had to cross, so I felt even more intimidated. Looking at the newsstand at the center of the plaza as if it were something dazzling, my legs feeble, body clumsily bent, comically yes, I was about to step forward . . . when, as if utterly unrelated to our conversations up to then, my friend spoke furiously. Her language, too, had switched from English to French, her tone challenging:

“I can’t understand why you see a film like “Dr. Strangelove” and aren’t put off by the way wars and nuclear weapons are treated in it.”

***

Reflecting on this experience on a summer morning in Cambridge that lasted only a few seconds, I am led in two directions. Toward two books, but the latter in particular, which allows me to link to my essential sense of America.

The first book is what The Saturday Review called “a novella of a hair-raising racial protest like a scream in the dark” that the black writer Chester Himes published in the year World War II ended: If He Hollers Let Him Go. There is a black youth. The war begins, and he is working at a shipyard; he is in love with a daughter of a prosperous black elite family. He is a youth with potential who plans to go to college once the war is over. But from a certain moment on, he becomes a completely scared human being. Or he ends up noticing that he is a human being who has been scared throughout his life. The black youth comes to be hunted down for an attempted rape through trickery by a white female worker. After being captured and jailed, he is eventually sent to the military. Why did the youth end up becoming so scared, and how did he come to realize that he had been scared all his life?

When the war started, the youth saw Japanese Nisei in Los Angeles being sent to the camps. “Maybe it had started then, I’m not sure, or maybe it wasn’t until I’d seen them send the Japanese away that I’d noticed it. Little Riki Oyana singing ‘God Bless America’ and going to Santa Anita with his parents next day. It was taking a man up by the roots and locking him up without a chance. Without a trial. Without a charge. Without even giving him a chance to say one word. It was thinking about if they ever did that to me, Robert Jones, Mrs. Jones’s dark son, that started me getting scared.”3

That morning in Cambridge, I was identifying with both the Japanese Nisei being sent to a concentration camp and the black youth who began to be scared by having premonitions about his similar fate. Of course, no one came to take me up by the roots. But for nearly fifty days until that morning, since my arrival in America, I had not been scared for a single moment. I had not looked at myself with the caricaturing eyes of an American, that is, with the most sharply objectifying eyes that the Japanese in America could suffer. When I was watching TV with seminar comrades in the common room of the dormitory, even when more or less caricatured Japanese appeared on the screen, no one paid attention to me, and I couldn’t care less, either. In other words, for nearly fifty days, I had had the illusion of having blended into American society like a colorless solvent. But my experience that morning (to be fair, it was the only experience of that kind that occurred during my four-month stay in America) gave me, at least in the world of my consciousness, an opportunity to imagine the presence of the eyes of Americans looking at me with the most sharply caricaturizing intent, and an opportunity to reflect on it.

Now, the other book that I, guided by the experience that morning, began to think about afresh, is Adventures of Huckleberry Finn that happened to make my summer trouser pocket bulky. At that moment, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn in my trouser pocket, truly like a weight, stabbed vertically into the depths of my consciousness. To me Adventures of Huckleberry Finn was the only book by an American that I had loved to read through the time before and after the summer experience going back twenty years from that moment, but until then, I had not thought that it had any special meaning, nor had I thought about why I had cut it off from my extremely complicated inferiority complex toward America through the time before and after the summer twenty years earlier. I came to think, I must examine anew what kind of image of a human being Adventures of Huckleberry Finn had continued to have for me. Why was it that for me, Huckleberry Finn was for some reason thought to be different from an ordinary American? Isn’t Huckleberry Finn the most popular hero to boys in today’s America as well? And also, have I not found, among the heroes of postwar American literature authors who must have grown up reading Huckleberry Finn, the heirs of Huckleberry Finn? In The Adventures of Augie March, in The Deer Park, in From Here to Eternity, in Catcher in the Rye, in Rabbit, Run. The twentieth-century Huckleberry Finn who drove a car across the highways that cover the entire American land, instead of a raft floating down the Mississippi River, is the hero of On the Road. It is not that, when traveling by car in America, I had not understood that the car provides spiritual and physical experiences similar to that of a raft one hundred years ago. About this, I must write in greater detail on another occasion.

In the midst of the Second World War, at a time when I was seeking to avoid being consumed by feelings of enmity, loathing, contempt, and terror of everything American, Adventures of Huckleberry Finn first came to my attention. And in no time Huckleberry became the first hero I acquired through literature. I cannot remember who my benefactor was who gave me the Iwanami paperback edition of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, translated by Nakamura Tameji, but thinking that it was my late father allowed me to have the best memory of him.

To the story of Huckleberry, by order of the author, the chief of ordnance, 1st Infantry Regiment, Royal Guard, England, added a caution: “Persons attempting to find a motive in this narrative will be prosecuted; persons attempting to find a moral in it will be banished; persons attempting to find a plot in it will be shot.” So I became passionate about neither the motive, nor the moral, nor the plot, but about one image. It was a terrifying image of Huckleberry Finn going to hell. It is natural for a wartime child to think more often about death than a peacetime child. The teacher of my elementary school (kokumin gakko) often tested us thus: “Come, tell me, if His Majesty the Emperor tells you to die, what will you do?”

The expected answer was, I will die, sir, I will disembowel myself and die. Of course, I was sure in some way that His Majesty the Emperor was unlikely to come all the way to a village in a valley like this looking for me, a dirty little thing, but in repeating this solemn lie about death so many times, it seemed that I ceased to feel any connection to the word hell.

After his cavern exploration with Tom Sawyer (also a unique hero, but I was never attracted to him), Huckleberry was adopted by a strict and mannerly widow, and removed from his drifter’s life. But Huckleberry was tormented by that new life. “The widow’s sister tried to educate him.4 Then she told me all about the bad place, and I said I wished I was there. She got mad, then, but I didn’t mean no harm. All I wanted was to go somewheres; all I wanted was a change, I warn’t particular.”

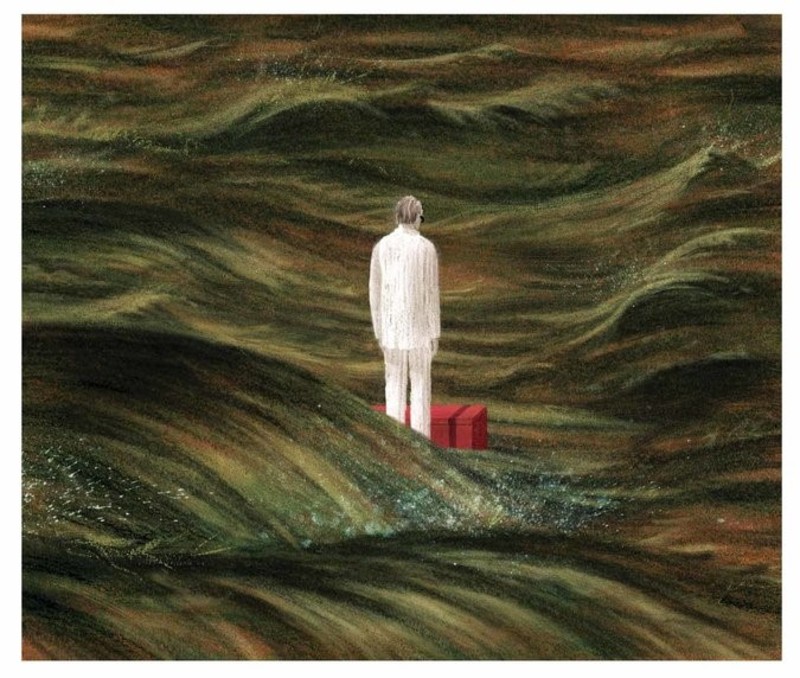

In the end Huckleberry set out on a journey with the black slave Jim floating down the Mississippi River on a raft. The same Jim creates a profound dilemma for him, and Huckleberry ends up confronting his own hell.

“Jim said it made him all over trembly and feverish to be so close to freedom. Well, I can tell you it made me all over trembly and feverish, too, to hear him, because I begun to get it through my head that he was most free—and who was to blame for it? Why, me. I couldn’t get that out of my conscience, no how nor no way. It got to troubling me so I couldn’t rest; I couldn’t stay still in one place. It hadn’t ever come home to me before, what this thing was that I was doing. But now it did; and it staid with me, and scorched me more and more. I tried to make out to myself that I warn’t to blame, because I didn’t run him off from his rightful owner, but it warn’t no use.”

“It would get all around, that Huck Finn helped a nigger to get his freedom; and if I was to ever see anybody from that town again, I’d be ready to get down and lick his boots for shame. That’s just the way: a person does a low-down thing, and then he don’t want to take no consequences of it. Thinks as long as he can hide it, it ain’t no disgrace. That was my fix exactly. The more I studied about this, the more my conscience went to grinding me, and the more wicked and low-down and ornery I got to feeling. And at last, when it hit me all of a sudden that here was the plain hand of Providence slapping me in the face and letting me know my wickedness was being watched all the time from up there in heaven, whilst I was stealing a poor old woman’s nigger that hadn’t ever done me no harm, and now was showing me there’s One that’s always on the lookout, and ain’t agoing to allow no such miserable doings to go only just so fur and no further, I most dropped in my tracks I was so scared.”

After such troubling thoughts, Huckleberry writes a letter secretly telling the rightful owner that a white man has happened to capture Jim, and then must decide whether to send it or not. “It was a close place. I took it up, and held it in my hand. I was a trembling, because I’d got to decide, forever, betwixt two things, and I knowed it. I studied a minute, sort of holding my breath, and then says to myself:

“‘All right, then, I’ll go to hell’—and tore it up.

“It was awful thoughts, and awful words, but they was said. And I let them stay said; and never thought no more about reforming. I shoved the whole thing out of my head; and said I would take up wickedness again, which was in my line, being brung up to it, and the other warn’t. And for a starter, I would go to work and steal Jim out of slavery again; and if I could think up anything worse, I would do that, too; because as long as I was in, and in for good, I might as well go the whole hog.”

Compared with Tom Sawyer who is inside the social order, Huckleberry, who is outside society, freely chooses hell for his own sake. In doing so, Huckleberry must have enabled our side, Japanese children, to observe him as a free hero who was not glued to America, in any of the eras influenced by fear or hatred of America, or total dependence on America. Furthermore, now, I thought I often discovered in the world of civilization of today’s America something resembling an attitude toward nature deeply chiseled with nature and superstitions, following the antisocial flight of Huckleberry in the age of great forests and rivers. Needless to say, I do not say this in the schematic grasp of human beings as hip and square, since the fad of the Beat Generation. That is, this does not about the superficial amusement of finding the heirs of Huckleberry in hippies and calling all other average Americans squares, along with Tom Sawyer. Rather, in my clear and extensive impression that I might even call classical, I felt, in today’s America, for example on New York’s Fifth Avenue, the existence of Americans with their destitute hearts listening to the calls of nighthawks and the barking of dogs in the depths of forests. I think I will think about it anew as one way the Americans who are the descendants of Oscar Handlin’s so-called “uprooted” (The Uprooted, the Grosset’s Universal Library edition) can still be in the great forest of ultra-modern civilization.

Recommended citation: Ōe Kenzaburō, “Huckleberry Finn and the American Dream in the Shadow of the Vietnam War”, The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Vol. 13, Issue 43, No. 1, October 26, 2015.

Notes

- See Hiroaki Sato, “Great Tokyo Air Raid was a war crime”

- Curtis LeMay, with MacKinlay Kantor, Mission with LeMay: My Story (Doubleday, 1965).

- Chester Himes, If He Hollers Let Him Go, with a foreword by Hilton Als (Thunder’s Mouth Press, 2002), p. 3.

- Ōe includes this sentence, obviously his own, in the quotation.