Patients Adrift: The Elderly and Japan’s Life-Threatening Health Reforms

Hiratate Hideaki

Translation by John Junkerman

Part 1: Changes in Elderly Medical Care Invite Lonely Death

Nakata Takako, 85, runs a small furniture store in Osaka. She lives alone in a wood-frame building that contains both her residence and the shop. Married during the war, she and her husband started the business after the war ended. They raised two daughters. Her husband died some 25 years ago, and she has run the business alone since then.

However, business has declined in recent years, and the shop produces almost no income. Nakata no longer restocks her inventory. Her monthly pension of less than 40,000 yen is all she has available for living expenses. Life is difficult, but she does not want to impose on her daughters.

Two years ago, Nakata was hospitalized with kidney disease. Her weight dropped from 43 kilograms to 34. Her kidney function is now less than half of normal, and she requires medication. She visits the hospital monthly for checkups, and her medication runs 3000 yen per month. Despite living on a pension, she is burdened with annual payments of 44,000 yen for national health and long-term care insurance.

Moreover, under the new system of medical care for the elderly, insurance fees will be withheld in advance from Nakata’s pension payments. “Really, they’re putting the burden on the poorest of us,” she remarks, as dark clouds loom over her livelihood.

Discarding the Elderly

In April 2008, Japan will introduce a new elderly medical care system for people over the age of 75 (Kôki Kôreisha Iryô Seido). Some 13 million people will be removed from the national health insurance system and required to enter the new system.

The current health service program for the elderly (Rôjin Hoken Seido) is funded by contributions from the national and local governments, along with the national and other insurance programs. Half of the funding for the new system will come from the national and local governments, forty percent from the insurance programs, and ten percent from the insurance fees of the beneficiaries. In addition, there will be a co-payment of ten percent for medical services and drugs, which rises to thirty percent for those with income equivalent to active wage earners (more than 5.2 million yen in annual income).

The system will be administered by wide-area alliances, which are groupings of local governments that all cities and towns throughout Japan are members of. Insurance fees will be set by these alliances, with a portion of the fee being a fixed rate and the remainder proportional to income. The Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare has estimated the monthly fee at 6,200 yen for an average pensioner, but the Tokyo metropolitan government has generated an estimate of 9,500 yen, and the fee will be different in each region of the country. This means that, for example, even the two million elderly who are being supported by their income-earning children will face the burden of a new insurance fee. Low-income elderly, living alone and receiving the minimum pension, will be given a seventy percent reduction in the fixed-rate fee and will be charged no income-based fee. But the fees are to be reviewed every two years, and as medical costs rise, there is the possibility that insurance fees will be raised or services curtailed.

The insurance fees will be withheld from pension payments of more than 15,000 yen per month. Failure to pay the fee will result in revocation of one’s insurance card and the issuance of a “qualification certificate.” This is a penalty sanction that will require full payment for medical services. Under the present elderly health insurance program, these certificates could not be issued to people over the age of 70. Now these elderly, with their reduced disease resistance and higher dependence on medical care, will be subject to these sanctions under this new, stonehearted system.

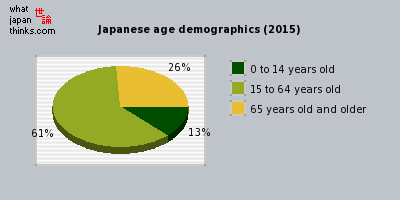

Japanese age distribution 2006 and 2015

Japanese age distribution 2006 and 2015

Mr. A, 78, and his wife, 72, live on their own. Their combined pensions are less than 70,000 yen per month. Mrs. A, who has pancreatic disease, qualifies for care under the national long-term care insurance program, and she visits the hospital twice a month. To get there, she has to use a taxi. Each trip to the hospital, including transportation and medication, costs the couple more than 20,000 yen.

For 54 years, Mr. A has taken in contract dressmaking work. During Japan’s high-growth era, he had employees working for him, but now he works alone and earns about 120,000 yen per month. Since their pension payments are exhausted by their hospital visits, the couple lives on his dressmaking income. In three years, both of them will fall under the new insurance program. “As I get older,” Mr. A says quietly, “it gets harder to work. I’m not sure how much longer I’ll have income.”

The problems with the new system are not limited to its economic burden. The payment schedule for medical treatment is independent of other insurance programs, and it is on a fixed-cost, blanket system. The allowable expense per month is set in advance for each disease. If necessary exams and treatment are cut off because of these limits, it is a de facto restriction of medical care. This is nothing short of the government delivering a death sentence, telling the elderly to die quickly. Will Nakata and Mr. and Mrs. A be able to survive this new system?

Stripping the Long-Term Care Beds

The medical-care environment surrounding the elderly is deteriorating quickly. In 2005, the government called for a major reduction in the number of long-term care beds in hospitals. Of the 370,000 such beds available in 2006, all of the 120,000 long-term nursing care beds (those covered by the long-term care insurance program) will be eliminated, and 100,000 of the remaining 250,000 long-term medical care beds (covered by health insurance) will be cut by the end of 2011. Long-term care beds will be restricted to patients with high need for medical care, while those with less acute need for care will be transferred to their homes or to residences for the elderly. This strong-arm policy guidance is intended to do away with what is called “social hospitalization” (hospital stays that are prolonged for social reasons rather than out of medical necessity).

Long-term medical care beds are essential for patients in need of extended care. However, in 2006 the government revised the payment schedule for long-term beds, creating a classification grid with three medical categories and three ADL (activities of daily living) categories, or nine classifications in all. Payments were slashed for medical category 1 patients, those with a low necessity for medical care. As a result, hospitals caring for a large number of these category 1 patients can no longer do so economically. Cases have begun to appear of patients being pressured to leave the hospital or being refused admission.

One serious problem is that category 1 patients include those who are bedridden and require sputum aspiration or tube feeding. They may not require specialized treatment, but medical care is still essential. To take away beds from elderly patients who need medical supervision and facilities amounts to “discarding” the elderly.

The Osaka Medical Practitioners Association surveyed 76 medical institutions in the city, asking whether they would discharge patients categorized as having a low necessity of medical care. Forty-two institutions replied that they would recommend discharge, but some patients would not be able to be discharged. Thirty-two of the institutions responded that most of these patients could not be discharged. In other words, 97 percent of the institutions responded that they would have difficulty discharging these patients. The numerous reasons cited included the following: “There is no facility to transfer them to.” “The patient lives alone, with no one to care for him/her.” “The patient suffers from dementia and in-home care is difficult.” “The only caregiver is an elderly spouse.” “There are medical complications.” “Housing problems.”

Furthermore, in 2005 fees for room and board (“hotel costs”) began to be assessed to patients in long-term care, and some patients have been forced to leave the hospital for financial reasons. Since the specialized nursing homes that are intended to take in these patients are already filled to capacity, the situation is particularly grave.

Hospitals are hard pressed to respond to the changes. Some have abandoned long-term care and switched their beds over to general medical care. However, to do so means meeting higher staffing levels for doctors and nurses. The government intends to shift long-term care beds to elderly health service facilities, but that is not a simple matter. Whereas hospitals are required to provide 6.4 square meters of space per patient, the elderly service facilities must provide 8.0 square meters. The larger space requirement means fewer beds. In addition, the cost of refitting facilities to compensate for lower payments represents a heavy burden.

After medical care for the elderly over 70 was made free in 1973, long-term care hospitals functioned to provide medical care to the elderly, within the context of a generally frail nursing care system. With the introduction of Long-Term Care Insurance (Kaigo Hoken Seido) in 2000, the government systematized long-term care, distinguishing the medical functions of long-term beds and general medical beds. This provided a powerful push for provision of long-term care beds.

However, the new policy of reducing the number of long-term care beds in hospitals changes the situation dramatically. “[The government] removed the ladder from under us,” comments Matsuda Takahiro, the administrator of Kita Hospital in Kyoto. The hospital maintains seven long-term care beds, and fifty-three nursing-care beds. At the time of the introduction of Long-Term Care Insurance, the hospital spent 800 million yen on a new building, replacing its general medical care beds with long-term care beds.

When the government stopped reimbursing for “hotel costs,” the hospital lost 2 million yen a month in income, and it has lost another 400,000 under the new payment schedule. It has covered the losses by reducing salary bonuses to employees and contracting out its food service.

There are countless hospitals like Kita that took out loans to rebuild and provide facilities that would allow them to survive in Japan’s aging society. Despite this, the government has shifted course within the space of a few years toward eliminating long-term care beds, resulting in widespread distrust of government. Some hospitals, lacking the prospect of viable business, are likely to close, while others may go bankrupt from the burden of multiple layers of debt. The price for cutting beds and eliminating hospitals will, in the end, be paid by the patients.

The State of Home Healthcare

Behind the introduction of the new elderly medical care system and the reduction of long-term care beds is the government’s hidden agenda to dramatically reduce the cost of healthcare. Total payments for medical treatments were reduced in 2006 by 3.16 percent, paring approximately one trillion yen from the national health bill of thirty trillion yen. The total number of days for hospital stays contracted, and the imposition of time limits on rehabilitation regimens has meant that some patients had their assistance discontinued before they were fully recovered. Further, in a country where more than eighty percent of the people die in hospitals, efforts are being made to transfer elderly patients from hospitals to residential facilities, such as in-home care and fee-charging elderly service providers, in order to reduce the cost of terminal medical care. To foster in-home care, entities called long-term in-home care support clinics have been established.

The Kamaishi Family Clinic in Kamaishi, Iwate Prefecture provides outpatient services, at the same time that it functions as one of these support clinics. Three doctors, including clinic director Terada Naohiro, and nine nurses look after more than three hundred at-home patients.

Terada had staffed the in-home care department of the Kamaishi City Hospital, but when that hospital merged with the Iwate Prefectural Kamaishi Hospital in April 2007, it was unclear how the needs of at-home patients would be met. Unwilling to leave his bedridden patients to their own devices, Terada decided to open a clinic for outpatient and in-home care, in part of the building that used to house the city hospital. At the same time, a private long-term care hospital had opened, providing backup support for the in-home care. With the availability of hospital beds, “patients can rest assured,” Terada says. “We were able to provide uninterrupted care,” despite the hospital merger.

Support clinics are required to provide house calls 24-hours a day and visiting nurse services. In turn, the government provided the clinics with a generous payment schedule. For example, the allowance for terminal care, attending a patient within 24 hours of his or her death, was raised from 1000 to 10,000 points (each point presently worth ten yen). Perhaps drawn by this payment schedule, some ten thousand clinics have registered as support clinics. But there are people in medical circles who question whether these clinics can actually deliver the required services. This is because the requirement to provide round-the-clock house calls is a high hurdle for doctors who are also seeing outpatients during the day.

The Shimada Clinic in Osaka is staffed by two doctors, including owner Shimada Ichiro, and seven nurses. The clinic services about fifty at-home patients, but it has not registered as a support clinic. House calls are scheduled around morning and afternoon outpatient office hours, but with travel time included, only two calls can be made in an hour. In addition to seeing patients, there are charts and referrals and opinions to be written, as well as accounting, and Shimada often doesn’t make it home before 1 a.m. Physically unable to handle the demands of round-the-clock, year-round house call availability, Shimada says, “Even if we wanted to, the question of whether we could provide adequate treatment 24-hours a day makes me uneasy.” It’s difficult to manage this unless a doctor is part of a regional network of practicing physicians who share the burden. One of the issues facing local medical associations is how to construct such networks to provide sufficient in-home care and to correct regional imbalances in the availability of support clinics.

The importance of in-home medical care will only increase in the future. Family problems often come into play with regard to the content of in-home care. Not only doctors, but nurses, care managers, and aides are required to work together, sharing information and developing common approaches.

But in the end, in-home care depends on the family’s ability to provide. The increase in the payment schedule for in-home care has also meant an increase in the financial burden on the patient. In other words, adequate in-home care is limited to those elderly patients who are blessed with both sufficient care-giving and financial ability.

Revisions to the long-term care insurance program continue to undermine families’ ability to provide care. Japan’s expenditure on healthcare, as a percentage of GDP, is the lowest of the developed countries (8 percent in 2004, compared to 15.3 percent in the US, and about 10 percent in Germany, France, and Canada, for example), while the co-payment burden is the highest. At a time when Japan is facing the accelerated aging of its population, health spending needs to be increased. As things stand, elderly patients without family and financial resources will be left to drift, with no place to turn, and finally to face a lonely death.

Part 2: Physician Shortage Causing Regional Healthcare Collapse

Sasayama in Hyogo Prefecture, with a population of 44,000, is an old castle town where historic residences of samurai still line the streets. At the center of the city is the Hyogo College of Medicine Sasayama Hospital. Converted from a national hospital in 1997, it has provided emergency services to the local area.

However, in January 2007, a prefectural policy committee deliberating the region’s medical infrastructure announced a plan to merge the hospital’s obstetrics and pediatric units with the Hyogo Prefectural Kaibara Hospital in Tamba. Sasayama Hospital has only one physician in each of these units. Merging them could lead to a situation where the hospital’s continued existence is at risk. This has caused concern in the community, and an organization has been formed by hospital and area labor unions to push for improved medical care.

The organization has launched petition campaigns to pressure the prefecture to maintain the hospital and full medical services, while also inviting physicians to study sessions that raise awareness among the citizens. There is a sense of crisis that, without obstetric and pediatric care, people will not feel secure about having and raising children in the area, which could accelerate a trend toward depopulation.

Obstetrics Units Closing throughout Japan

The merger of obstetrics units has also caused disruption in Tamba, the city that neighbors Sasayama. There, the seventy-year old Kaibara Red Cross Hospital has performed two hundred deliveries annually, while receiving three thousand emergency room visits. It is a core hospital for the Tamba area.

However, in March 2007, the obstetrics unit of the Red Cross Hospital was consolidated with the prefectural Kaibara Hospital and the three staff physicians were let go. But the prefectural hospital was unable to handle the increased number of deliveries, and it has had to impose restrictions on “satogaeri shussan,” young women who return from big cities to give birth in their hometown.

Further, after the closure of the Red Cross Hospital obstetrics unit, the number of staff physicians dropped from thirteen two years ago to only four. The surgery and orthopedics units have also been forced to suspend operations. There is now only one part-time pediatrician. The hospital was unable to keep its emergency room open 24-hours a day, and the number of beds has been reduced from 100 to 55. The closure of the obstetrics unit has put the hospital’s continued operation at risk.

The decrease in obstetrics units is not unique to the Tamba region. According to a survey by the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, there were six thousand obstetrics facilities in 2002; by 2005, this number had fallen to three thousand. In addition to a shortage of obstetricians, the growing number of facilities that have discontinued deliveries out of safety concerns has exacerbated the situation. In 2006, a pregnant woman who died while being shuffled from hospital to hospital in Nara Prefecture made national news, and there were numerous cases of women suffering miscarriages in ambulances on their way to the hospital last year.

“The tragedy in Nara hits close to home,” remarks an individual associated with the Iwate Prefectural Isawa Hospital in the city of Oshu. Isawa Hospital had performed 550 deliveries annually, the most in the prefecture. Especially after the obstetrics unit of an Oshu city hospital closed, it was the only medical facility available that performed high-risk deliveries.

However, in May 2007 two of the three staff obstetricians left the hospital on maternity leave and retirement, and the unit was merged into the prefectural Kitakami Hospital. As a result, in cases of high-risk deliveries, the patient must be taken by ambulance to Kitakami or Ichinoseki, putting the mother and baby’s life in potential danger. Midwives working out of maternity hospitals now operate without physician backup.

A midwife in Tono in northern japan conducts an examination. In communities like this, urban obstetricians receive data by remote on their cell phones to advise women when they should go to an urban hospital to give birth.

A midwife in Tono in northern japan conducts an examination. In communities like this, urban obstetricians receive data by remote on their cell phones to advise women when they should go to an urban hospital to give birth.

Pediatric units are likewise endangered. According to the Ministry of Health surveys, 3,938 hospitals had pediatric units in 1994, but this number had fallen to 3,231 by 2004. At the same time, the system for providing nighttime emergency pediatric care has weakened.

At Isawa Hospital there is now only one pediatrician on staff, and local residents are worried that service may be suspended in the future. The region around Oshu had many practicing physicians and provided a level of medical care second only to the prefectural capital Morioka. But the collapse of the medical support system for maternity and child-rearing has resulted in a crisis in regional healthcare and is a cause of great concern to the residents.

Towns Rocked by “Medical Depopulation”

An increasingly serious shortage of physicians lies behind the closure of obstetrics and pediatric units at Japan’s hospitals.

There are about 270,000 practicing physicians in Japan, or 2.0 per one thousand population. The OECD average is 3.1, and Japan ranks 27th out of the 30 member countries. Japan has the lowest ratio among the G7 industrialized economies (the US stands at 2.4, Germany and France at 3.4). To reach the OECD average, Japan would need to add some 140,000 doctors.

In this context, Japan introduced a new clinical training program in 2004. Post-graduate clinical training was made mandatory, but because the trainees were allowed to freely choose the hospitals they train in, some university medical departments left with no trainees then withdrew doctors who had been dispatched to associated hospitals, thus exacerbating the shortage problem.

Another factor at play is the intense workload of hospital-staff physicians. According to a survey by the Japan Federation of Medical Workers Unions, three in ten staff physicians put in over eighty overtime hours a month, which is considered the risk threshold for karoshi (death from overwork). More than eighty percent of these doctors work continuous shifts of 32 hours more than three times a month (including nighttime on-call duty). These workloads have led increasing numbers of doctors to quit hospital work. For female doctors, the difficulties this poses for having and raising children contributes to the problem. The low level of Japan’s spending on healthcare and the policies it has adopted to reduce medical costs are also seen as contributing to the shortage of physicians.

At the same time, since hospitals depend on payments for services rendered, the shortage of physicians puts pressure on hospital finances and has forced public hospitals to curtail or suspend their operations.

Nagano Red Cross Kamiyamada Hospital was a 250-bed general hospital in Chikuma, Nagano Prefecture. However, it lost many physicians after the introduction of the new clinical training program and this, in combination with the 2006 reduction in the fee payment schedule, resulted in financial difficulties. In 2008, the hospital will close its wards and become an outpatient clinic, and it will close entirely the following year.

Kamiyamada Hospital maintained a visiting nurse base station and provided support to many at-home elderly patients. When it becomes an outpatient clinic, its hospitalized patients will have to be moved to other hospitals, and when it closes for good, the elderly patients will be abandoned. Local residents complain that they will be unable to take their elderly family members the long distance to a new hospital for checkups, and they worry about the lack of nighttime emergency room services.

Public hospitals run by regional governments have also begun to close. Iwate Prefecture has operated twenty-seven hospitals, more than any prefecture, servicing one third of the hospitalized patients and one half of the outpatients in the region. However, under a five-year reform plan for the prefectural hospitals adopted in 2003, the hospitals were reorganized into core hospitals that provide specialized medical care, and local hospitals and clinics that provide initial medical care.

Five of the prefectural hospitals were to be reduced to outpatient clinics by 2008. One of these, Ohasama Hospital in the city of Hanamaki, was converted to a clinic in April 2007. A 50-bed hospital that was established in 1950, it was renovated in 2001 to provide essential medical services to the 6,500 residents of the town of Ohasama.

Then in 2003 it was designated for conversion to outpatient clinic status. Local resident Sasaki Isao, 76, recalls, “After building that beautiful hospital, to turn it into a clinic was just making fools of all of us.” Sasaki and others established the Committee to Defend Ohasama’s Health and Welfare, circulated petitions demanding the hospital be kept open, and appealed to the prefectural assembly. The assembly rejected their request, but a revision was made that allowed the clinic to maintain nineteen beds for inpatients. However, the ophthalmology, orthopedics, and cardiovascular units are staffed by part-time physicians, and at-home medical services have been curtailed. There have been reports of patients dying because of the suspension of medical services.

Because the clinics are affiliated to core hospitals, they do not control their own budgets. “In the future, they may well eliminate the beds, or shut down the clinic entirely,” Sasaki worries. There are only four buses a day from Ohasama to the prefectural Hanamaki Kosei Hospital, and that hospital itself is slated to merge with Kitakami Hospital in 2008. This will be even further away, and so far there is no bus service in place. Without the assurance of adequate healthcare, young couples will not settle in the area. Twenty-five percent of population of Hanamaki is over 65, and the percentage is higher in Ohasama. The trend is toward leaving the elderly behind in these “medically depopulated” towns.

Consolidation Betrayed

The situation along the coast in Iwate is even more dire. The prefectural hospital in Kuji is an emergency sub-center, but it has been unable to hire a fulltime anesthetist. At the prefectural hospital in Miyako, there is no staff physician in the cardiovascular unit. At the prefectural hospital in Rikuzentakata, there is no pediatrician. Meanwhile, the obstetrics unit of the prefectural hospital in Kamaishi has merged with the unit at the prefectural hospital in Ofunato, while Ofunato’s cardiovascular unit has been consolidated with the unit at Kamaishi. However, though such consolidations are meant to compensate for the shortage of physicians, they do not always result in improvements in regional healthcare.

In Kamaishi, the city hospital and the prefectural hospital were consolidated in April 2007. The city hospital had no staff physicians in pediatrics or obstetrics, and was running a growing deficit. In September 2004, the city announced a consolidation plan based on predictions of continuing population loss and a surplus of beds at the two hospitals. “By consolidating with the prefectural hospital as a core hospital, one plus one will equal two, or maybe three,” the city claimed.

But the prefectural hospital did not increase its capacity, and the fourteen physicians from the city hospital were not given positions at the consolidated hospital. It was clear that merging staff was difficult, when they come from different medical departments and work environments. The result was not the “consolidation” of two hospitals, but simply the elimination of the city hospital.

Local citizens pay the price. Where the city hospital was in the center of town, the prefectural hospital is located six kilometers away. With patients now concentrated at one hospital, outpatient visits now require day-long waits. And the units for ear, nose and throat care, orthopedics, ophthalmology, and respiratory diseases are all staffed by part-time physicians. Given this state of affairs, even people associated with hospitals complain that, “Far from being a plus, the consolidation was a minus.”

Even before consolidation, the prefectural hospital’s emergency room was under heavy demand, and it was not rare for people to die en route to the hospital. It takes more than two hours by ambulance to get to an alternative emergency room in the capital city of Morioka. Closing the city hospital, which handled six hundred emergency cases a year, puts the city’s residents’ lives at risk. With a mix of resignation and fear, residents say, “You can’t get sick in Kamaishi.” “If you get sick, all you can do is die.” The burden of healthcare has more and more become an individual’s responsibility.

In Fukushima Prefecture, the National Fukushima Hospital in Sukakawa merged with the national hospital in Koriyama in 2004. At the time of the merger, Fukushima Hospital was planned to have twenty treatment units, with four hundred beds and a staff of forty-five physicians. There were plans for a neonatal intensive care unit and a center for the treatment of severe mental and physical handicaps. Area residents had particularly high expectations for the planned construction of a cardiovascular unit. This was because there were no public hospitals in the central part of the prefecture, and it took more than two hours by ambulance to get to private hospitals in Koriyama.

However, the hospital was only able to hire one third of the projected staff of physicians, and the number of treatment units was pared to twelve. The 50-bed internal medicine ward was closed, and the cardiovascular unit never got built.

Other local governments are attempting major reorganization of their healthcare systems. There are four public hospitals (city, national, Red Cross, and mutual insurance hospitals) in the city of Maizuru, Kyoto Prefecture, which provide services to the northern half of the prefecture and parts of neighboring Fukui Prefecture. These hospitals face the common problems of the shortage of physicians and cuts in the treatment payment schedule, while the number of hospital admissions and outpatient visits have been decreasing. If things are left as they are, all four hospitals could fail and regional healthcare would collapse.

In 2004, there was a confrontation between Maizuru City Hospital and the city’s mayor over operating deficits at the hospital, which led to the resignation of the entire internal medicine staff, and the forced removal of 150 hospitalized patients in what amounted to a closure of the hospital. Seeking to avoid a repeat of this bitter clash, the city has put together a committee to discuss the status of healthcare in the region and ways to most effectively make use of the available resources. An interim report proposes reorganizing the public hospitals into two, or possibly one. But the variety of hospital administrations and the barriers between various medical departments pose issues that remain to be resolved.

The collapse of regional healthcare has been caused by the shortage of physicians and the policy of reducing medical expenditures. This is clearly a failure of national healthcare policy. Drastic measures need to be taken to increase the number of physicians and to boost funding for medical treatment. The disappearance of hospitals has become a reality, and the right to receive medical care is being taken away. Japan must not become an archipelago of healthcare in ruins.

Hiratate Hideaki is a journalist, and the author of Shikatsu Line: “Utsukushii Kuni” no Genjitsu” [Life and Death: The Reality of the “Beautiful Nation”]. This article appeared in the November 2 and November 16, 2007 issues of Shukan Kin’yobi. John Junkerman, a Japan Focus associate and documentary filmmaker living in Tokyo translated the article for Japan Focus. His film, “Japan’s Peace Constitution” is distributed in North American by First Run Icarus Films. Posted on March 11, 2008.

See John Creighton Campbell, The Health of Japan’s Medical Care System: “Patients Adrift?” for a discussion of this article.

http://japanfocus.org/-John_Creighton-Campbell/2730