For The All Okinawa Council

Between 15 and 21 November 2015, the “All-Okinawa Council” (shimagurumi kaigi) – an Okinawan mass organization set up in July 2014 representing local communities, civil society groups, local assemblies, and business establishments – dispatched a 26-member delegation to San Francisco and Washington D.C, to present the Okinawan stance of unshakable opposition to any new base construction in Okinawa. Prominent Okinawan businessman, and chair of the Kanehide industrial and property group, Goya Morimasa, led the delegation, and the paper that follows is the document in which All Okinawa presented its case.

The Council’s mission to the US may not have produced any obvious political outcomes but it served to spread the Okinawa message, gaining attention from important media and nature conservancy organizations, eliciting potentially important support from the principal American labour organization, the AFL-CIO, and presenting a persuasive case for understanding the “Okinawa problem” or “Henoko problem” as not just a ”Japanese” matter but one in which the US government is deeply involved and US laws have been and are being infringed. The accompanying “Statement” makes that very clear. (GMcC)

Position Statement

A New U.S. Military Base Must Not be Built in Okinawa

Okinawa’s Opposition to the Construction of a New U.S. Base at Henoko (Okinawa) and the Responsibility of the U.S.

Summary

The nineteen-year controversy over the U.S. and Japanese governments’ plan to relocate US Marine Air Station Futenma to Henoko (the Henoko base construction plan) in the northern part of Japan’s Okinawa Island is at a critical juncture.

Deeply concerned over this, the All-Okinawa Council has dispatched this mission to present the Okinawan case to the United States. The All-Okinawa Council is a civil society organization with a membership of over 2000 individuals from local communities, civil society groups, local assemblies, and business establishments.

|

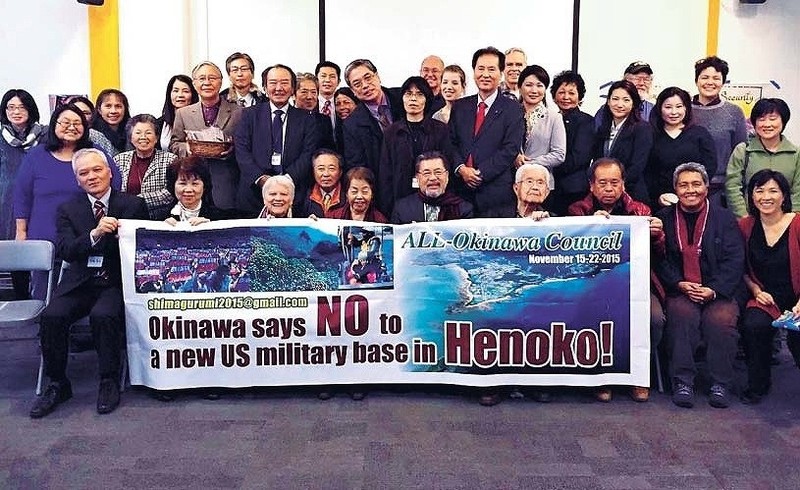

The “All Okinawa” Mission to the US, November 2015 |

On October 13, 2015, supported by an overwhelming majority of the people of Okinawa, Okinawa’s Governor Onaga Takeshi revoked the land reclamation approval for the construction of the U.S. military base granted under heavy pressure from the Japanese government in December 2013 by his predecessor, Nakaima Hirokazu. Governor Onaga’s revocation was based upon a review of the approval process conducted by a Third Party (Experts) Commission, which concluded that Nakaima’s approval had many legal flaws. With the act of revocation by Governor Onaga, the construction and related activities became illegal, and in fact the Japanese government temporarily halted them.

However, the Japanese government quickly acted to file complaints in an attempt to suspend and nullify Governor Onaga’s revocation. It declared its intention to take the issue of Governor Onaga’s revocation to court and to reinstate or “execute by proxy” the land reclamation approval. On October 29 it suspended Governor Onaga’s revocation and resume construction works and on November 12 it resumed drilling surveys.

These events are deeply disturbing to Okinawa. Opposition to the Henoko base construction plan (never lower than 70 per cent and in some cases even higher than 80 per cent in surveys over the past several years) reaches unprecedented levels. Confrontation between protesters and riot police forces escalates at Camp Schwab, the existing U.S. military base, part of which is to be incorporated into the projected new base. Day after day, protesters are arrested and detained and on occasion suffer injuries. Litigation between the Okinawa prefectural government and Japanese governments is imminent.

Meanwhile, the U.S. government appears to be merely an “active bystander.” While maintaining the position that “both the U.S. and the Japanese governments remain committed to implementing the relocation of Marine Corps Air Station Futenma to Camp Schwab on Henoko Bay,” it regards the Henoko plan as “a done deal” and a Japanese “domestic issue.” The U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) keeps issuing entrance permits to Camp Schwab so that the Okinawa Defense Bureau can continue its illegal construction works and drilling surveys.

Demands

Given this situation, the All-Okinawa Council calls upon the government of the United States to reconsider its position in regard to the Henoko base construction plan.

First, we call upon the U.S. government to acknowledge and respect the fact that the democratic voice of the people of Okinawa, manifested in the form of repeated elections, resolutions by the Prefectural Assembly (Okinawa’s parliament), mass rallies, public forums, sit-ins, and now civil disobedience, unequivocally opposes the construction plan.

Second, we call upon the U.S. government to cease issuing entrance permits to the Okinawa Defense Bureau to the Oura Bay site for construction purposes for the following two reasons:

(a) Because Governor Onaga has revoked the approval for reclamation granted by his predecessor, Governor Nakaima, and because litigation between the Okinawa prefectural government and the Japanese government is imminent over the legality of reclamation, and

(b) Because Governor Onaga’s revocation challenges the DoD’s conclusion that reclamation would have “no adverse effects on the dugong” (the endangered marine mammal and Japanese Natural Monument inhabiting the Henoko vicinity). The report of the third party (experts) commission, on which Governor Onaga’s revocation was based, clearly states that “it is easily predicted that the impacts of land reclamation [on the dugong] will be serious.” (p. 87).1 As the DoD’s conclusion was based upon its analysis of the Japanese government EIA and the study it commissioned in 2010, it needs now to review its position.

Third, we hold to the view that the values of democracy, justice, mutual understanding and trust are the underlying principles of the relationship between the U.S. and Japan, and we therefore urge both the administrative and legislative branches of the U.S. government to take the responsibility set forth by US laws and administrative agencies and international standards.

We also call the attention of the Government of the United States to the “Resolution in Support of the People of Okinawa” adopted by Berkeley City Council in September 2015.2 That Resolution demanded that:

1) The Department of Defense (DoD) undertakes an appropriate and sufficient “take into account” process as ordered by the Court under the NHPA;

2) The US Marine Mammal Commission reviews and comments on the DoD’s analysis of effects of the base on the dugong;

3) Congressional hearings take up environmental issues in the Henoko base construction plan;

4) Congressional hearings be conducted that address the lack of democratic process over the siting of this base in Okinawa;

5) Pending satisfactory resolution of the above four matters, the U.S. government should abandon base construction works at Henoko.

These are just and proper demands.

Once the U.S. government decides to address its responsibility and fulfil its legal obligations, the only logical conclusion that it can reach is that the U.S. Marine Air Station Futenma should be closed immediately and unconditionally and that the plan to construct a new U.S. base at Henoko must be cancelled.

Background

The Henoko construction plan emerged as a response to the rape of a twelve-year schoolgirl by three U.S. soldiers in Okinawa in 1995 and to the outrage and demand for base reversion it sparked. Many people of Okinawa regarded the crime as an inevitable consequence of the injustice that Okinawa, with only 0.6 % of Japan’s entire landmass, has to bear about 74% of all the US military bases and facilities in Japan.3 In response, the U.S. and Japanese governments established the Special Action Committee on Okinawa (SACO) “to reduce the burden on the people of Okinawa and thereby strengthen the Japan-US alliance.”4

In 1996, SACO drew a plan to close the U.S. Marine Corps Air Station Futenma (Futemna), situated in the middle of the crowded Ginowan City, and to relocate it to Henoko, Oura Bay, Nago City, in the northern part of Okinawa Island. It was reasoned that the area of Henoko and Oura Bay was “less congested.” The target year for the completion of the base was set at 2004.

Immediately after the plan to relocate from Futenma to Henoko was made public, the people of Okinawa began to oppose it. For a majority of the people of Okinawa, any relocation plan within Okinawa could not be regarded as “reducing the burden on the people of Okinawa.” The Japanese government however began to employ carrot and stick tactics, pouring money into local communities in the form of development projects and relocation-related funds, in the hope that the local communities would accept the relocation of Futenma to Henoko.

By 1999, then Okinawa Governor Inamine Keiichi and then Nago City Mayor Kishimoto Tateo had “accepted” the first Henoko plan, for construction of an air base with a 2,000 meters runway offshore on the reef’s edge at Henoko. However, that “acceptance” was hedged by conditions (especially that of a 15-year term and joint civil-military usage), which were unacceptable to either the U.S. or the Japanese government.5 The Japanese government nonetheless began preliminary survey works in the waters of Henoko in 2004. These survey works faced fierce protest from local people for political, environmental and quality of life reasons. Protesters occupied survey platforms day and night, and sit-ins and rallies took place on the land. The preliminary survey works were stopped and eventually this first Henoko plan was withdrawn in 2005.

In May 2006, the “U.S.-Japan Roadmap for Realignment Implementation” spelled out the second Henoko construction plan (the current plan).6 It called for the construction of a base featuring two 1,800 meter-runways in a V-shape, extending from the existing U.S. Marine Corps facility at Camp Schwab into Oura Bay to the west and Henoko Bay to the east. The target year for the completion of the base was set at 2014.

In 2007, the Okinawa Defense Bureau (ODB) began its Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) process in accord with this design. Four years later in 2011, it released an Environmental Impact Statement, concluding that the Henoko base construction would have no significant impact on the environment.7

In February 2012, then Governor Nakaima, who was elected in 2010 on a platform not to allow the relocation of Futenma within Okinawa, submitted his “Governor’s Comments” on the ODB’s EIA statement. His comments questioned the validity of the EIA and stated:

(the construction) should cause tremendous problems in terms of environmental conservation,” “even with the conservation measures provided in the EIA, the conservation of the livelihood of the local people and of the environment in the area affected is impossible.”8

Those comments reflected the absurdity of the Henoko base construction plan. Designated as “Assessment Rank I” (the highest) in the Okinawa Prefectural Government’s Guidelines on the Conservation of the Natural Environment, the area of Henko and Oura Bay is one of the most biodiversity rich areas in Japan with some 5.300 marine species including 260 endangered ones.9 The Henoko construction plan requires dumping of twenty-one million cubic meters of sand and rock (more than 3 million truck-loads of sand and rock) into this area to reclaim land for the construction of the base.10

The U.S. Congress also questioned the feasibility of the Henoko base construction plan. In April 2012, in a letter sent to Defense Security Panetta, members of the U.S. Senate Armed Services Committee, Senators Levin, McCain and Webb, expressed their concerns for the feasibility of the Henoko base construction plan.11

In October 2012, then Governor Nakaima submitted an official letter to the U.S. government entitled “Promotion of Resolutions for the U.S. Military Base Issues”.

He wrote:

I believe that the Henoko Plan, which is opposed by the City Assembly of Nago where Henoko is located, the Okinawa Prefectural Assembly, and all 41 municipality leaders within Okinawa, would be virtually infeasible. In order to implement Futenma relocation plan, a relocation site outside of Okinawa Prefecture, but within Japan, is the most logical way to speedily move forward. Therefore, Okinawa Prefectural Government wants MCAS Futenma moved off Okinawa.12

In 2013, however, the Japanese government wielded “unprecedented pressure and inducements” (in the words of the Congressional Research Service) to persuade local politicians of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party to reverse their previous stance and accept the Henoko plan.13 This paved the way for then Governor Nakaima to reverse his previous stance, to adopt the Final Environmental Impact Statement’s “no impact on the environment” conclusion, and to grant approval for reclamation in the waters of Henoko and Oura Bay in December 2013. His approval was regarded by the U.S. government as an “apparent breakthrough on Futenma base relocation.”14 It was understood that all administrative and legal obstacles for the construction of the base had been cleared.

In this context, however, Okinawa stepped up its decisive opposition to the Henoko construction plan. In January 2014, the Okinawa Prefectural Assembly passed an unprecedented resolution calling for resignation of Nakaima for his granting of land reclamation approval.15 Rallies, sit-ins, public forums took place, criticizing then Governor Nakaima’s betrayal. Opposition also manifested in the mayoral election in Nago City in January 2014 when the incumbent Susumu Inamine defeated by a large margin his opponent backed by then Governor Nakaima and the Japanese government.16 In the consequent Nago Assembly elections, candidates who opposed the Henoko construction plan won the majority of the assembly seats. The Japanese government nonetheless continued preparations for drilling surveys and construction works.

Construction Works and the Responsibility of the U.S. Government17

While then Governor Nakaima’s approval of the land reclamation was necessary for the construction of the base, it was not sufficient for actual construction works to start. The base to be built is a U.S. base, and the base will be built in part on Camp Schwab, and land reclamation is to be carried out in the waters surrounding the base. That means that, according to the Status of Forces Agreement the U.S. Department of Defense has to provide access to Camp Schwab to the Japanese government (Okinawa Defense Bureau).18 And provision of such assess is not automatic.

In 2003 Okinawan individuals and Japanese and U.S. environmental organizations filed suit in the U.S. Federal Court for the Northern District of California San Francisco Division against the U.S. DoD under the National Historical Preservation Act (NHPA). In 2008, the Court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, finding that the DoD failed to take into account the impacts of the base on the Okinawa dugong required by Section 402 of the NHPA.19 The Court ordered the DoD to comply with the law by “taking into account” the effects of the base on the dugong prior to engaging in any “federal undertaking.” The two sides began consulting with each other to figure out how the “taking into account” procedures should be carried out.

In February 2012, however, the Court decided to hold the case in abeyance until “plans for Henoko become more finalized or are abandoned.”20 It reasoned that “the matters to be considered by defendants and then by the court [were] far from finalized.” Indeed, in the same month that the Court made this decision, then Governor Nakaima submitted his “Governor’s Comments” questioning and criticizing the Japanese EIA for the Henoko base construction plan.

In April 2014, four months after then Governor Nakaima granted land reclamation approval, the U.S. DoD unexpectedly notified the Court and the plaintiffs that it had completed the “take into account” process and submitted the U.S. Marine Corps Recommended Findings April 2014 (the Findings).21 Based upon both the DoD’s analysis of the Japanese government (Okinawa Defense Bureau’s) EIA and the study it commissioned in 2010, the Findings concluded that the Henoko base “will have no significant adverse impact” on the dugong.22 This conclusion enabled the U.S. DoD to issue entrance permits to the Okinawa Defense Bureau to enter Camp Schwab as well as the waters surrounding the base to start drilling surveys and construction works. On July 1, 2014, as the U.S. DoD issued permits to ODB and its hired construction workers, they entered Camp Schwab and began clearing the ground on the base.

The start of construction works was met with fierce protest from local citizens and local governments. An around the clock sit-in began in front of the main gate of Camp Schwab and protesters in boats and kayaks began their protest against the drilling surveys at the sea. Public opinion polls recorded opposition to the construction plan at 80 percent in August 2014.23

In response, the Japanese government began to use a more heavy-handed approach to force the Henoko base construction plan forward. It sent riot police and a fleet of the Japan Coast Guard’s ships and boats to contain and capture protesters.24 In consultation with the U.S. government, it also created new “temporary restricted water areas,” expanding the previous off-limit zone of 50 meters off-shore from Camp Schwab to two kilometers.

Meanwhile, the U.S. government began to describe the Henoko base construction plan as “a done deal” and a Japanese “domestic issue,” while the U.S. DoD kept issuing entrance permits to the Okinawa Defense Bureau to Camp Schwab. The San Francisco court, despite having ruled in favor of the plaintiff Okinawans in 2008, also adopted a similar stance.

In July 2014, the plaintiffs filed a supplementary complaint, arguing that despite the U.S. DoD’s submission of the Findings, the DoD had not fulfilled the Court’s 2008 order in terms of either procedure or substance.25 According to the complaint, the plaintiffs were not informed that the DoD was engaging in the “take into account” process. The DoD has not made public the related documents, or its translations and analysis of the Japanese EIA documents. The plaintiffs asked the Court to order the DoD to comply with the NHPA. In February 2015, the Court dismissed the plaintiffs’ complaint, citing treaty considerations and the court’s inability to redress the case.26 The Court declared:

“The Court lacks the power to or any competence to enjoin or otherwise interfere with the construction of a U.S. military facility overseas that is being built consistent with American treaty obligations and in cooperation with the Japanese government.”

“While this Court does have the power to grant Plaintiffs’ request for declaratory relief that the DoD did not comply with the NHPA, and similarly has the power to order the DoD’s NHPA findings set aside, the Court will nevertheless grant the Government’s motion to dismiss these claims because any action the Court takes with respect to the NHPA findings will not redress Plaintiffs’ injuries.”

The DoD justified its issuing of entrance permits to the Okinawa Defense Bureau on the grounds that the administrative and legal procedures on the Japanese side had been cleared and that the DoD had conducted its “take into account” process ordered by the Court and found that the base “will have no adverse effects on the dugong.”

New (from December 2014) Governor Onaga Takeshi and His Revocation of Land Reclamation Approval27

In late 2014, Okinawa’s opposition to the Henoko base construction plan scored decisive electoral victories. In October, Onaga Takeshi who ran on a platform of not allowing the construction of the base defeated by a large margin the incumbent Governor Nakaima.28 In the December National Diet elections, all four Okinawan electorates returned candidates who opposed the construction, in all cases soundly defeating opponents who had approved the Henoko base construction plan.29 Tellingly, the Japanese government halted drilling surveys and construction works during the period of these elections.

After taking over governorship in December 2014, Governor Onaga began to apply his administrative power and authority to stop the construction plan. Most notably, he began challenging the land reclamation approval, which many regarded as flawed and problematic. In January 2015, Governor Onaga assembled a commission of experts, legal and environmental, to review the process of then Governor Nakaima’s approval of land reclamation for the Henoko base construction. The Third Party (experts) Commission was tasked with finding out whether if there were any legal flaws in then Governor Nakaima’s approval. If there were any, Governor Onaga would use them as grounds for revoking the land reclamation approval. The Commission spent the next six months meticulously examining documents, interviewing prefectural officers who had been involved in the approval process, and consulting with other experts. In July 2015, the Committee submitted its 132-page report to Governor Onaga. It found that there were indeed many legal flaws in the process of Nakaima’s approval of land reclamation.30

On October 13, 2015, based on the Commission’s report, Governor Onaga revoked the land reclamation approval, making the construction and related works illegal. Prior to doing so, Onaga insisted to the United Nations Human Rights Council in Geneva in September that the construction of the base would be in violation of the right to self-determination of the people of Okinawa and declaring that he would use any means at his disposal to stop it.31

The Japanese government responded quickly to Governor Onaga’s revocation. It launched two different, but related, moves in attempt to suspend and nullify it, and to reinstate or “execute by proxy” the land reclamation approval.

First, on October 14, the day after Governor Onaga revoked the approval, the Okinawa Defense Bureau (OBD) filed a complaint and a request for stay of execution with the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (MLITT), asking it to review, suspend, and nullify Governor Onaga’s revocation under the Administrative Appeal Act.32 ODB maintains that “there were no flaws with the land reclamation approval made in late 2013 and that Governor Onaga’s revocation disposition is illegal.” On October 27, Minster Ishii Keiichi of MLITT suspended Onaga’s revocation while the validity of the revocation is being examined by MLITT.33 The minister reasoned that if not the revocation suspended, “the Japan-US alliance could be adversely affected” and his decision enabled the construction work to resume on October 29.

On November 2, Governor Onaga retaliated against the Minister’s suspension of his revocation by filing a complaint with the Central and Local Government Dispute Management Council. He reiterated that there were flaws in the land reclamation approval process and argued that the ODB’s using the Administrative Appeal Act was unjustified because the law is reserved for individual citizens who have been subjected to unjustified or illegal acts by governmental agencies, not for the national government.34 Now the issue is also being examined by the management council, which is expected to deliver its decision by the end of January 2016. Meanwhile, construction work at Henoko continues.

Second, on October 27, the MLITT minister sent Governor Onaga a “correction recommendation” that Governor retract his revocation by November 6, which Governor Onaga steadfastly rejected.35 On November 9, the Minister stepped up the level of pressure by issuing a “correction instruction” that Governor Onaga retract the revocation by November 13. This too Governor Onaga rejected.36 These moves by the MLITT are considered part of the Japanese government’s design to take the issue to court and to enable the MLITT minister to reinstate or “execute by proxy” the land reclamation approval.37 The Okinawa prefectural government is also preparing for court battles.

Lawyers and experts have expressed concern that the Japanese government’s moves are illegal.38

Meanwhile, as construction works resumed and continued, protesters began engaging in civil disobedience at the gates of Camp Schwab. Since construction works resumed on October 29, protesters come to blockade the gates of Camp Schwab, putting their bodies in front of and underneath construction vehicles. Riot police are dispatched to remove protesters. Day after day, protesters are arrested and detained and on occasion suffer injuries.39 And now with so much frustration on the part of protesters, protest actions are sometimes directed towards U.S. military personnel entering Camp Schwab through the main gate.

Governor Onaga’s Revocation and the Responsibility of the U.S. Government

The critical situation surrounding the issue of the Henoko base construction plan is currently centered on two developments: litigation, now imminent, between the Okinawa prefectural government and the Japanese government, and the ongoing confrontation between protesters and riot police at Camp Schwab and in the waters surrounding the base, in which the authorities increasingly resort to violence against a resolutely non-violent opposition.

The U.S. government holds to the position of “active bystander,” insisting that “Both the U.S. and the Japanese government remain committed to implementing the relocation of Marine Corps Air Station Futenma to Camp Schwab on Henoko Bay.”40 This position accords with statements issued by U.S. government officials and U.S. Congress, including U.S. Ambassador to Japan Caroline Kennedy, that the Henoko base construction plan is “the only solution that addresses operational, political, financial, and strategic concerns.”41

|

All Okinawa meets AFL-CIO, Washington, November 20, 2015. |

Photo: Tomoyose Motoki

We at All Okinawa Council argue otherwise. The issue is far from over and it is in need of critical review. The U.S. government bears heavy and distinctive responsibilities regarding the Henoko base construction plan that we hereby call upon it to fulfil. Our demands are as set out above in this document.

Contact: [email protected].

November 15, 2015

Recommended citation: Yoshikawa Hideki and The All Okinawa Council, “All Okinawa Goes to Washington – The Okinawan Appeal to the American Government and People”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 49, No. 3, December 7, 2015.

Author

This paper was prepared for the All Okinawa Council by its joint representative, Yoshikawa Hideki, an anthropologist who teaches at Meio University and the University of the Ryukyus in Okinawa and is also the International director of the Save the Dugong Campaign Center and former Chief Executive Director of the Citizens’ Network for Biodiversity in Okinawa.” For his other writings in English, see the Asia-Pacific Journal index.

Notes

1 Kensho kekka hokokusho [Report on Examination Results], The Third Party Commission, July 16, 2015.

2 Item 36 “Resolution in Support of the People of Okinawa”

3 Okinawa no beigun kichi (Okinawa prefecture 2013).

4 The SACO Final Report, December 2, 1996.

5 Official letters exchanged in 1999 between Governor Inamine Keiichi, Nago Mayor Kishimoto Tateo and the Japanese government.

6 U.S. and Japan Roadmap for Realignment Implementation, May 2006.

7 Futenma hiko jyo daitai shisetsu kensetsu jigyo ni kakaru kankyo eikyo hyouka [Environmental Impact Assessment for the Construction of Futenma Replacement Facilities] The Ministry of Defense.

8 See the “Governor’s Comments”.

9 Futenma hiko jyo daitai shisetsu kensetsu jigyo ni kakaru kankyo eikyo hyouka [Environmental Impact Assessment for the Construction of Futenma Replacement Facilities] The Ministry of Defense.

10 See the “Letter of Request” sent by Citizens’ Network for Biodiversity in Okinawa and other NGOs to the Invasive Species Specialist Group, International Union for Conservation of Nature.

11 “Senators Levin, McCain and Webb Express Concern to Secretary Panetta Regarding Asia-Pacific Basing,” cited in Emma Chanlett-Avery and Ian E. Rinehart The U.S. Military Presence in Okinawa and the Futenma Base Controversy, Congressional Research Service, August 14, 2014. (updating previous report dated August 3, 2012, with the same title)

12 Copies of the letter (Ref. No. 660, dated on October 22, 2012) were submitted to the U.S. government officials including Secretary of the State Hillary Rodham Clinton on the occasion of then Governor Nakaima’s visit to the U.S.

13 Chanlett-Avery and Rinehart, op. cit.

14 Ibid.

15 “U.S. base at center of Nago poll” by Eric Johnston, Japan Times, January 11, 2014.

16 “Nago mayor wins re-election in blow to Abe, U.S.” by Eric Johnston, Japan Times, January 19, 2014.

17 See Hideki Yoshikawa “Okinawan Appeal to the US Congress: Futenma Marine Base Relocation and its Environmental Impact: U.S. Responsibility,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 12, Issue 39, No. 3, September 24, 2014.

18 Article III-1 of the Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) between the U.S. and Japan reads “Within the facilities and areas, the United States may take all the necessary measures necessary for their establishment, operation, safeguarding and control.”

19 See the Court’s decision.

20 See Center for Biological Diversity, et al., Plaintiff(s), vs. Leon Panetta, Secretary of Defense, et el., Defendant(s). Case3:03-cv-04350-MHP Document147. The chronology of the case is summarized in the First Supplemental Complaint submitted by the Plaintiffs. See the First Supplemental Complaint.

21 U.S. Marine Corps Recommended Findings April 2014 (Exhibit 1)

22 In July 2009, at the direction of the San Francisco court, the US Marine Corps appointed a group of experts – an ethnographer, an archaeologist, archival researchers, and a marine biologist – to investigate the cultural significance of the dugong. The Corps then relied on that report, sometimes known as “Welch 2010,” in reaching its conclusion that the base project “will have no adverse effect on the dugong.” However, the Corps’ reluctance to make the findings public is enough to rouse suspicions that that may not be so. (Exhibit 1, ibid.)

23 “Yoron chosa henoko chushi hachijyu pasento isetus kyoko hanpatus hirogaru [Public Opinion Polls: With the Government’s heavy handed approaches, 80 percent oppose the Henoko plan], Ryukyu shimpo, August 26, 2014.

24 “Tokyo steamrolling U.S. base plan ahead of Okinawa Governor race,” Asahi shimbun, August 15, 2014.

See also “Thousands march on Henoko base site,” Jon Mitchell, Japan Times, August 23, 2014.

25 First Supplementary Complaint for Declaratory and Injunctive Relief.

26 Amended Order Granting Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss.

27 See Gavan McCormack, “Okinawa as Sacrificial Victim”, Le Monde Diplomatique, October 25, 2015.

28 “Okinawa elects anti-base governor, in rebuke to Abe,” Eric Johnston, Japan Times. November 16, 2014.

29 “LDP loses heavily in Okinawa,” Japan Times, December 15, 2014.

30 “Okinawa Experts Commission Reports Flaws in Authorization Process for New Military Base at Henoko,” translated by Sandi Aritza, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue. 29, No. 3. July 20, 2015.

See also Kunitoshi Sakurai, “To whom does the sea belong? Questions Posed by the Henoko Assessment,” (translated by Gavan McCormack), The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue. 29, No. 4, July 20, 2015.

Sakurai Kunitoshi is a prominent member of the Third Party Commission and the Sakurai paper is the most extended discussion of the issue currently available in English.

31 “Onaga takes base argument to U.N. human rights panel,” Alastair Wanklyn, Japan Times, September 22, 2015.

32 Press Conference by the Defense Minister Nakatani. October 13, 2015.

See also “Minister delivers counterattack over Okinawa’s repeal of Futenma landfill work,” Japan Times, October 14, 2015.

33 Press Conference by the Defense Minister Nakatani, October 27, 2015.

See also “Minister voids Okinawan Governor’s blockage of Futenma landfill work,” Japan Times, October.

34 Minister of Defense, Gen Nakatani states that “I understand that those who can appeal are not restricted to “citizens,” and that more broadly, “those who have a complaint with the disposition” are permitted to appeal. Accordingly, in general, it is construed that a central or local government agency is eligible to appeal if it receives a disposition in the same capacity as a general business operator or the like.”

35 Press Conference by the Defense Minister Nakatani, October 27, 2015.

See also “Okinawa snubs response over landfill approval revocation,” Japan Times, November 6, 2015.

36 Press Conference by the Defense Minster Nakatami, November 10, 2015.

See also “Okinawa rebuffs state order on landfill work, court battle looms,” Japan Times, November 11, 2015.

37 Press Conference by the Defense Minister Nakatani, October 27, 2015.

38 “Construction of an outlaw marine base in Henoko,” Lawrence Repeta, Japan Times, November, 15, 2015.

39 “Henoko ni kidotai hyakunin ijyodouin, shimin haijo, kegano uttae [Over 100 riot police dispatched to remove citizens, injuries claimed], Okinawa Times, October 31, 2015.

40 State Department Daily Briefing by Mark Toner, October 13, 2015.

41 Press Release: Ambassador Kennedy’s Meeting with Okinawa Governor Onaga, June 19, 2015.