Korean War Traumas

Heonik Kwon

This is the first of two paired articles which view the U.S.-Korean War through the lens not of great power conflict, or even of civil war, but from the perspective of its impact on Korean society in countryside and city, and the continuing traumas that remain unresolved sixty years late. The second article is

Han Kyung-koo, Legacies of War: The Korean War – 60 Years On.

Soi dau is a familiar expression for people of the war generation in the southern and central regions of Vietnam (the regions that comprised South Vietnam before 1975). The term soi dau refers to the Vietnamese ceremonial delicacy made of white rice flour and black beans. Used as a metaphor, it also conveys how people of this region experienced the Vietnam War (1961-1975). In the latter context, soi dau refers to the turbulent conditions of communal life during the war, when the rural inhabitants were confronted with successive occupations by conflicting political and military forces: at night the village was under the control of the revolutionary forces and in daytime opposition forces took control. Life in these villages oscillated between two different political worlds governed by means of two hostile military forces. The people had to cope with their separate yet total assertions for absolute loyalty and with the world changing politically day and night, over many days and nights, to the extent that this anomalous world sometimes appeared to be almost normal.

One side came and seized food and young people from families; the other side came and punished those who had provided food and labor to the enemy. One group came and asked the locals, “Are you with us?” The locals said with one voice, “We are with you, totally and always.” Sometimes the soldiers didn’t believe what the villagers said, no matter how vigorously and sincerely the villagers asserted their loyalty, and this often—much more often than the existing history books tell us—resulted in tragic incidents.

|

Children survey the ruins of their village in South Vietnam |

The traces of these incidents are still vigorously alive in many Vietnamese villagers in the form of unremarkable village mass graves or in other less tangible forms such as apparitions by grievous spirits of the dead. Soi dau conveys the simple truth that when you eat this sweet, you must swallow both the white and black parts. This is how soi dau is supposed to be eaten, and this is what it was like living the tumultuous life in the village seized under the brutal dynamics of Vietnam’s civil and international war.

|

Interrogation by South Vietnamese forces |

The histories of the Vietnam War and the Korean War are closely interrelated in the historiography of the Cold War. The lived realities of these wars, likewise, had many common features. Members of the war generation of Koreans are aware of many expressions similar in meaning to soi dau, although these may not necessarily take the metaphor of food and ingestion as is the case in Vietnam. In her story, In the Realm of Buddha, the eminent South Korean novelist Park Wan-suh speaks of a woman’s enduring, troubling memory of the Korean War as if this was an alien object stuck in her throat which she is neither able to swallow nor spit out. [1] Kim Song-chil, a history professor, kept a diary of occupied Seoul from June 28 to September 28, 1950. [2] Among the many amazing things his diary tells us, we learn how confused the historian felt when he had to change the flag on the door of his house; from the South Korean to the North Korean national flag and later back to the South Korean one. We also learn how the war and occupation distorted intimate human relations of trust. One of Kim’s neighbors joined the occupying authority and was active in the town’s People’s Committee. The neighbor’s wife and Kim’s wife were close to each other, having had a long relationship of neighborly intimacy and mutual support. The neighbor’s wife was worried about her husband’s pro-North activity and what would happen to her family if the world changed again. She confided her worries in the historian’s wife, the one person in her neighborhood she genuinely trusted. Kim’s wife wished to comfort her but couldn’t say much, however, knowing that if she said the wrong things to her neighbor, and if the woman’s husband heard about what she had said, that might bring calamity to her own family. Park Wan-suh’s other biographical writings tell similar stories about the breakdown of neighborly trust: her uncle’s house was requisitioned by occupying forces to provide an eating place for North Korean army officers. [3] Because of this, he was later arrested and executed when the tide of war changed and South Korean and U.S. troops recovered the town. Her uncle’s arrest was triggered by his neighbor who had accused him of being a “collaborator.” The polarization of society affected Park’s immediate family, too. Her brother, a schoolteacher, had been active in a radical political movement before the war started but, yielding to family pressure, he later signed up for the Alliance of Converts, the prewar South Korea public organization that was intended to re-educate the former radicals in the “right way” of anticommunist patriotism. When Seoul was occupied by the North, he was pressured by his former comrades to join the town’s civil support activities for the revolutionary war and subsequently conscripted into the North Korean People’s Army as a southern “volunteer.” When the tide of war changed and Seoul had new liberators, her brother’s past career and his absence from home became a life-threatening liability for Park’s family. In a desperate attempt to survive, Park Wan-suh, then a first-year college student of literature, joined an anticommunist paramilitary youth group as a secretarial clerk.

|

U.S. forces search a North Korean village |

These were traumatic experiences. They were not the same as the classical shell-shock familiar to the history of World War I; they were, nonetheless, no less destructive. These civil war traumas were different from the post-traumatic syndromes caused by the trench warfare in terms of their loci. The growing biographical, literary, and ethnographic accounts of the grassroots Korean War experience which have been made available in South Korea recently, make it abundantly clear that this war was a traumatic experience not only for the combatants but also for the many more unarmed civilians and people who had no professional role in the conflict. The traumas experienced by the civilian population were social traumas—both in distinction to combat traumas and, more importantly, because these were the traumas experienced by social persons and relational beings rather than necessarily by isolated individuals and their separate bodies. Indeed, “relation” or “relational trauma” appear to be key words in the recent literature about Korea’s civil war experience, as testified forcefully by the moving stories of Hyun Gil-on’s Gwangye (“relations” or “webs of relations”), an eminent contemporary South Korean writer of Jeju origin. [4] The relational trauma refers to the fact that the Korean War’s physical and political violence induced its brutal and enduring effects primarily into the milieu of intimate communal and family relations. It also testifies to the fact that the main thrust of the Korean War’s political violence actually targeted not merely the enemy soldiers’ physical bodies and their collective morale but also the morality and spirituality of intimate human communal ties.

|

Refugees at Inchon fleeing South on January 3, 1951 |

Some may argue that this is always the case in mass-mobilized modern wars, and especially in the king of all people’s wars in terms of brutality of war, modern civil war. There is a certain truth to this view, and I believe that there is merit in placing the Korean War experience in the broad comparative historical context of modern warfare. However, the social, human-relational traumas of the Korean War tell us not merely about the general human condition in the wars of the twentieth century but also convey the unique character and nature of the Korean conflict.

The Korean War was not a single war; it was rather a combination of several different kinds of war. It was a civil war, of course, waged between two mutually negating postcolonial political forces, each of which, through the negation, aspired to build a common, larger, singular and united modern nation-state. It was an international war fought, among others, between two of the most powerful states of the contemporary world, the United States and China. It was a global war waged between two bifurcating international political, moral, and economic forces having different visions of modernity, which we, for want of a better term, commonly call the Cold War. Hidden underneath these well-known characteristics of the Korean War, however, there was another kind of war going on in the Korean peninsula from 1950 to 1953. Steven Lee calls this war the Korean War’s war against the civilian population. [5] The South Korean sociologist Kim Dong-choon calls it “the other Korean War,” emphasizing the fact that the reality of this war is not well known in existing history or to the outside world or, for that matter, even to Koreans themselves. [6] The historian Park Chan-sung calls it “the war that went into the village,” highlighting the disparity between the Korean War history as a national narrative and that as village history. [7]

|

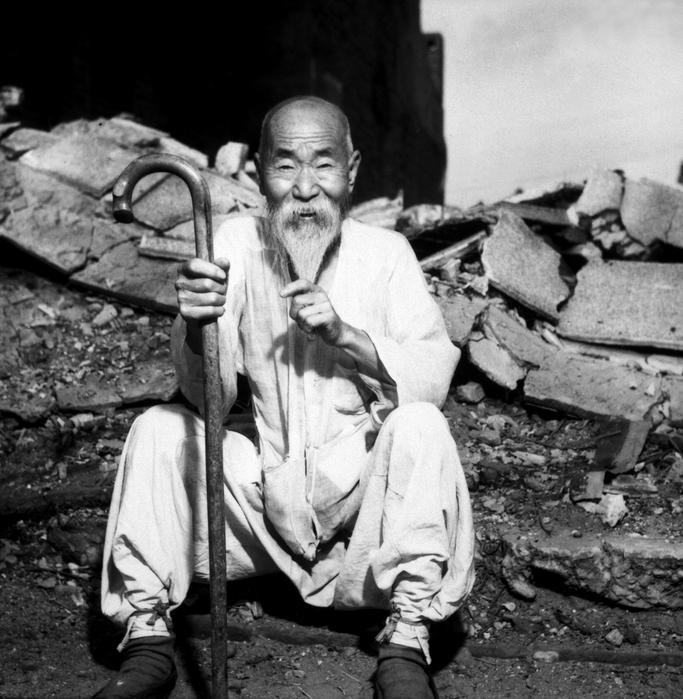

An old man rests in the ruins of Seoul Girl carries her brother in midst of war in the South |

What these scholars try to draw to our attention is the fact that the Korean War was not necessarily or primarily a violent struggle between contending armed forces. Instead, they show that the war was centrally about the struggle for survival by unarmed civilians against the generalized, indiscriminate violence perpetrated by the armed political forces of all sides.

The South Korean state committed preemptive violence in the early days of the war against hypothetical collaborators with the enemy (including numerous members of the Alliance of Converts), and this set in motion a vicious cycle of violence against civilians in the ensuing chaos of war: it radicalized the punitive actions perpetrated under North Korean occupation against the individuals and families who were classified as supporters of the southern regime, which in turn escalated the intensity of retaliatory violence directed against the so-called collaborators with the communist occupiers when the tide of war changed. When the North Korean forces left their briefly occupied territory in the South, they did the same thing as the South had done before and committed numerous atrocities of preemptive violence against people whom they considered to be potential collaborators with the southern regime.

The reality of the Korean War’s war against civilians became a subject of taboo after the war was over. South Koreans were not able to recall this reality publicly until recently, while living in a self-consciously anticommunist political society; the story of this war remains untold among North Koreans who, living in a self-consciously revolutionary political society, are obliged to follow the singular official narrative of war, a victorious war of liberation against American imperialism. But the stories of the Korean War’s other war existed throughout the postwar years in numerous communities and families: in whispered conversations among family and village elders; quiet talk among trusted relatives during family ancestral death-day ceremonies; in the silent agonies of parents who couldn’t tell their children the true stories of how their grandparents died during the war; the anxieties of aging parents who don’t know how to meet death without knowing about and hearing from their children whom they still want to believe are surviving on the other side of the bipolar border; in the furious self-expression of some forgotten ancestral spirits who intrude into a shamanic rite and thereby startle the family gathered there; in the anxious worries of two young lovers in a village who don’t understand why their families object to their marriage so furiously without providing any intelligible reason for doing so; and in the struggle of a grey-haired man who tries to reconcile with the memory of his mother who he long believed had abandoned him and who, he later discovered, had to abandon him in order to save him while being forced to marry the villager who was responsible for the death of his father and grandfather. These stories make up only a tiny fragment of the gigantic iceberg of the Korean War human dramas existing and still unfolding in Korea. Today, some of these dramas also involve courageous and innovative communal efforts to confront the Korean War’s enduring pains and wounds. [8]

The year 2010 marks the sixtieth anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean War. In traditional Korean custom, the sixtieth anniversary is an occasion of considerable cultural and moral import. It is when the community celebrates the longevity of sixty years, retraces the past years of intimate relationship, and gives blessings to prosperous future relations. It is also when Koreans believe, like other peoples of northeast Asia, that a new spirit of historical time emerges to replace the old. In the lunar calendar, 1950 was the year of the White Tiger, a time that comes once in every sixty years and which Koreans associate with the eruption of a historical event that may have great significance for peoples and communities. The war in the White Tiger year of 1950 was indeed a great historical event not only for Korea but also globally, although the greatness of this event was primarily destructive in nature. The year 2013 will mark the sixtieth anniversary of the end of the Korean War. In this traditional sensibility, moreover, the period between the two sixtieth anniversaries, 2010 and 2013, makes a vital time of commemoration and reflection. How people choose to commemorate the destruction of the Korean War during this period and how, accordingly, the history of destruction comes to take on new meanings, hopefully constructive and generative meanings, will surely have great relevance for the security and prosperity of the northeast Asian region and much beyond, not to mention the future of the two Koreas.

The South Korean anthropologist and Japan specialist Han Kyung-koo sets out to reflect on the meanings of the Korean War at the entry point to the war’s sixtieth anniversaries. Han is attentive to the horizon of the Korean War’s social traumas in their diverse manifestations. He argues that the Korean War resulted in “a virtual collapse of longstanding personal relationships and value systems.” However, he also observes that the destruction cleared the ground from which a new process of modernization and new normative order subsequently arose. We need to hear more of these thoughtful reflections on the historical meanings and social legacies of the Korean War, as we move closer to the sixtieth anniversary of the end of the Korean War in July 2013. This is in the hope that the totality of the Korean War, which continues to the present despite the fact that the guns went silent in July 1953, will be able to meet a genuine end with a formal peace treaty and establishment of mutual diplomatic relations among all parties to the war as it approaches the important anniversary occasion. The hope is that in 2013 Korea and its neighbors will be able to commemorate the Korean War, for the first time in modern history, in a celebratory atmosphere and in the way that truly merits the spirit of a sixtieth year anniversary in traditional Korean culture.

|

This article is part of a series commemorating the sixtieth anniversary of the Korean War. Other articles on the sixtieth anniversary of the US-Korean War outbreak are: • Mark Caprio, Neglected Questions on the “Forgotten War”: South Korea and the United States on the Eve of the Korean War. • Steven Lee, The United States, the United Nations, and the Second Occupation of Korea, 1950-1951. • Han Kyung-koo, Legacies of War: The Korean War – 60 Years On.

Additional articles on the US-Korean War include: • Mel Gurtov, From Korea to Vietnam: The Origins and Mindset of Postwar U.S. Interventionism. • Kim Dong-choon, The Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Korea: Uncovering the Hidden Korean War • Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Remembering the Unfinished Conflict: Museums and the Contested Memory of the Korean War. • Sheila • Tim Beal, Korean • Wada Haruki, From • Nan Kim |

Notes

[1] This essay is based on a speech delivered at the conference “The Korean War Today” at the Korea Society, New York, on September 10, 2010, as part of a sixtieth year Korean War anniversary event. I thank the Korea Society and Charles Armstrong for inviting me to this memorable occasion. The story “In the Realm of Buddha” by Park Wan-suh is available in English: The Red Room: Stories of Trauma in Contemporary Korea, translated by Bruce Fulton and Ju-chan Fulton (Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2009).

[2] Kim, Song-chil, In the Face of History: A Historian’s Diary of 6.25 (Seoul: Changbi, 1993, in Korean).

[3] Park, Wan-suh, Who Ate Up All the Shinga? An Autobiographical Novel, translated by Young-na Yu and Stephen Epstein (New York: Columbia University Press, 2009).

[4] Hyun, Gil-on, Relations (Seoul: Koryowon, 2001, in Korean).

[5] Steven Hugh Lee, The Korean War (New York: Longman, 2001).

[6] Kim, Dong-choon, The Unending Korean War: A Social History, translated by Sung-ok Kim (Larkspur, CA: Tamal Vista Publications, 2009), pp. 3-38. See this article.

[7] Park, Chan-sung, The Korean War That Went into the Village: The Korean War’s Small Village Wars (Paju, Kyunggi-do: Dolbege, 2010, in Korean).

[8] See this article.

Heonik Kwon teaches anthropology at the London School of Economics and Political Science. An Asia-Pacific Journal Associate, he is the author of After the Massacre: Commemoration and Consolation in Ha My and My Lai and Ghosts of War in Vietnam, which was awarded the first George Kahin prize by the Association for Asian Studies in 2009. His new book is The Other Cold War.

Recommended citation: Heonik Kwon, “Korean War Traumas,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 38-2-10, September 20, 2010.