Healing the Wounds of War: New Ancestral Shrines in Korea

Heonik KWON

Since the decades of authoritarian anticommunist rule ended in the late 1980s, and the geopolitical order of the cold war collapsed in the wider world shortly thereafter, there have been several important changes in the political life of South Koreans. One notable change is found in the domain of ritual life or, more specifically, in the activity of death commemoration and ancestor worship. In increasing numbers of communities across South Korea, people are now actively reshaping their communal ancestral rites into a more inclusive form, introducing demonstratively into the ritual domain the politically troubled memories of the dead, which were excluded from the public sphere under the state’s militant anticommunist policies.

It is argued that, for South Koreans, the prospect of genuine political democracy is inseparable from imagining an alternative public culture, free from the hegemony of anti-communism as an all encompassing state ideology.[1] In this context, overcoming the legacy of anti-communism is a necessary condition for the political community’s progress towards a post-cold war era, and thereby for joining the outside world, which, it is believed, has moved away from the grid of bipolar politics. Because the experience of the global cold war was exceptionally violent for Koreans, involving a catastrophic civil-and-international war, the above conceptualization of historical transition has involved myriad reflections and disputes about the nation’s violent past and its enduring effects.[2] This has been the case at the community level as well as nationally. The changes in ancestral rituals should be considered in this broad contemporary historical context, and as efforts to reconstitute the broken communal identity by restoring the normative aspect of its hidden genealogical heritage, which was outlawed by the state and stigmatized as a dangerous “red” (i.e. Communist) element in public consciousness.

Existing literature on South Korea’s democratic transition tends to focus on organized mass mobilization in the public sphere, notably the activism of dissident political leaders, intellectuals, students and the labor force. Although this focus is justified for a society where influential political discourses typically extend throughout the national society, it is also problematic through its lack of analytical attention to the organized actions and social developments taking place in local communities and more intimate spheres of life.[3] This article seeks to draw attention to processes of democratic transition at community level. It shows how communities, once devastated by violently bipolarizing political forces in the midst of the global cold war, are now struggling to overcome the wounds of past conflicts and violence, and how people in these communities are pressing for political justice and moral reconciliation. My discussion will focus mainly on Jeju Island at the southern maritime edge of the Korean peninsula, and will examine new ancestral shrines arising in parts of this island and the process of family and community repairs associated with these sites of memory. Although this process is not restricted to this region, the experience of Jeju provides an exemplary case in this matter.[4] The claims for justice and related activities of community repair developed in Jeju earlier than in most other parts of South Korea and have been particularly strong. I argue that the islanders’ new ancestral shrines not only demonstrate a process of genealogical reconstitution, but also constitute politically mixed religious shrines whose presence in the community testifies to both an enduring legacy of violent bipolar politics and a vigorous communal will to overcome this painful legacy. These developments interact with recent changes in South Korea’s domestic politics but also, more broadly, with the end of the cold war as a geopolitical paradigm of the last century. Therefore I will situate the islanders’ commemorative activities within a critical dialogue concerning an existing idea about social democracy after the cold war, and will show how this influential idea is based on a problematic understanding of bipolar political history, ignoring such violent realities as those endured by the Jeju islanders.

Jejudo

The democratic family is the backbone of successful political development beyond conventional left and right oppositions, writes the sociologist Anthony Giddens. Painting an outline of social democracy in the post-cold war world, Giddens repudiates both what he calls the “rightist” idealization of the traditional, patriarchal familial order and the “leftist” view of the family as a microcosm of an undemocratic political order. In their stead he proposes a new model of family relations, which in his view can synthesize the imperative of communal moral solidarity with the freedom of individual choice, as a unity based on contractual commitment among individual members. This social form of democratic family relations, according to him, will respect the norms of “equality, mutual respect, autonomy, [and] decision-making through communication and freedom from violence.”[5]

Giddens writes about family and kinship relations at length in a work devoted to the political history of bipolar ideologies because he believes that families are a basic institution of civil society and that a strong civil society is central to a successful social development beyond the legacy of left and right oppositions. His Third Way agenda is premised on the notion that new sociological thinking is demanded after the end of the cold war. According to him, political development after the cold war depends on how societies creatively inherit positive elements from both right and left ideological legacies, and its main constituents will be “states without enemies” (as opposed to states organized along the frontline of bipolar enmity), “cosmopolitan nations” (as opposed to the old nations pursuing nationalism), a “mixed economy” (between capitalism and socialism) and “active civil societies.” At the core of this hopeful, creative process of grafting, Giddens argues, are the “post-traditional” conditions of individual and collective life, an understanding of which requires transcending the traditional sociological imagination that sets individual freedom and communal solidarity as contrary values.[6] The “post-traditional” society, according to him, is expressed most prominently in the social life of “the democratic family.”

The merit of Giddens’s approach is that his view of the political transition from the cold war does not privilege the changes taking place in state identities and interstate relations. Instead, he relates these changes to other general issues in social structure, including individual identity and the relationship between state and society. For Giddens, “the new kinship” – based on mutual recognition of individual rights, active communal trust and tolerance of diversity – will be a key agent in making a general break with the era of politically bifurcated modernity, which appropriated individual freedom and collective solidarity into falsely contradictory, mutually exclusive categories.[7]

Giddens’s discussion of the social order after the cold war is based primarily on the specific historical context of Western Europe. In his accounts, the positions of “left and right” appear mainly as those about visions of modernity and schemes of social ordering. According to the Italian philosopher Noberto Bobbio, left and right are correlative positions, like two sides of a coin, in which “[the] existence of one presupposes the existence of the other, the only way to invalidate the adversary is to invalidate oneself.”[8] This privileged experience of left and right oppositions as both being integral parts of the body politic, however, may not extend to other historical realities of the cold war. In the latter, the left and right were mutually exclusive positions, rather than correlative ones, in the sense that taking the position of one side meant denying the other side a raison d’être, or even physically annihilating the latter from the political arena. In the situation of an ideologically charged armed conflict or systemic state violence, left or right might not be merely about an antithetical political distinction, but rather a question that is directly relevant to the preservation of human life and the protection of basic civil and human rights. Against this historical background of the cold war experienced as a “balance of terror” rather than “balance of power”[9], moreover, we may consider the relevance of family or kinship relations in the general social transition from the bipolar order with an approach that differs from Giddens’s.

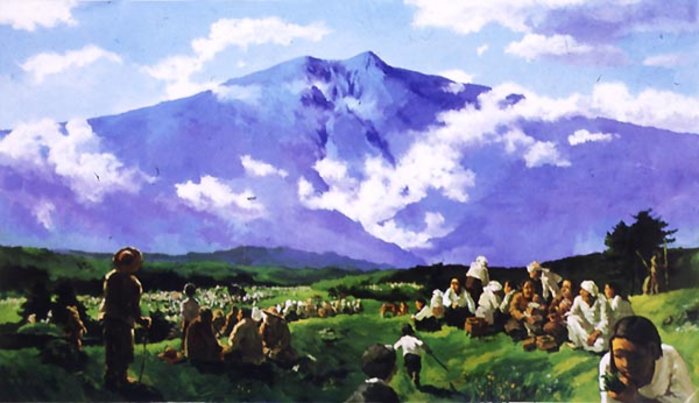

People of Jeju 1948, painting by Kang Yo-Bae

In April 2004, many places on Jeju Island were bustling with people preparing for their annual commemoration of the 4.3 (April 3rd) incident. The “incident” refers to the communist-led uprising triggered on 3 April 1948 in protest against both the measures undertaken by the United States’ occupying forces to root out radical nationalist forces from post-colonial Korea, and the policies of the US administration to establish an independent anticommunist state in the southern half of the Korean peninsula. But the reference is also to the numerous atrocities of civilian killings that devastated the island following the uprising, caused by brutal counterinsurgency military campaigns and counterattacks by communist partisans. This violent period was, in many ways, a prelude to the Korean War (1950-53).

Refugee Children of Jeju, May 1948

Hillside Villagers Evacuated to the Coastal Area

The 4.3 incident has only recently become a publicly acknowledged historical reality among the islanders, in contrast to the past decades during which the subject remained strictly taboo in public discourse. The situation has changed since the beginning of the 1990s and nowadays the islanders are free to hold death-anniversary rites for their relatives who were killed or who disappeared in the chaos of 1948. Every April, the whole island turns briefly into a gigantic ritual community consisting of thousands of separate but simultaneous family or community-based events of death commemoration.

The Commemoration of 4.3 Victims, Jeju Peace Park

The Chamber of 4.3 Victims, Jeju Peace Park

It is now a familiar experience for visitors to the island during the month of April to find themselves inadvertently party to a ritual occasion that the anthropologist Kim Seong-nae calls “the lamentations of the dead.” Presided over by local specialists in shamanic ritual, these occasions invite the spirits of those who have suffered a tragic death, offer food and money to them, and later enact the clearing of obstacles from their pathways to the nether world. A key element in this long and complex ritual procedure is when the invited spirits of the dead publicly tell of their grievous feelings and unfulfilled wishes through the ritual specialists’ speeches and songs. In a family-based performance, the lamentations of the dead typically begin with tearful narration of the moments of death, the horrors of violence and the expression of indignation against the unjust killing. Later, the ritual performance moves on to the stage where the spirits, now somewhat calmed down, engage with the surroundings and the participants. They express gratitude to their family for caring about their grievous feelings, and this is often accompanied by discussion (between the dead and the living, mediated by the ritual specialist) about the health of the family or its financial prospects. When the spirits of the dead start to express concerns about their living family, this is understood to mean that they have become free from the grid of sorrows, which the Koreans describe as a successful “disentanglement of grievous feelings.”[11]

In a ritual on a wider scale that involves participants beyond the family circle, the lamentations may include the spirits’ confused remarks about how they should relate to the strangers gathered for the occasion, which later typically develop into remarks of appreciation and gratitude. The spirits thank the participants for their demonstration of sympathy to the suffering of the dead, referring to those who have no blood ties to them and to whom, therefore, the participants have no ritual obligations. If the occasion is sponsored by an organization that has a particular moral or political objective, moreover, some of the invited spirits may proceed to make gestures of support for the organization. Thus, the spirit narration from the victims of a massacre may explicitly invoke concepts such as human rights if the ceremony is sponsored by a civil rights activist group, and other modern idioms such as gender equality if the occasion is supported by a network of feminist activists. The lamentations of the dead closely engage the diverse aspirations of the living.

Rite of Spirit Consolation, northern Jeju

Several observers of Korea’s modern history have noted that South Korea’s recent democratic transition, and the vigorous popular political mobilization since the late 1980s that enabled this transition, are not to be considered separately from the aesthetic power of ritualized lamentations.[12] The country’s civil rights groups disseminate the voices of the victims of state violence as a way of mobilizing public awareness and support for their cause, and employ forms of popular shamanic mortuary processions to materialize the dead victims’ messages. The lamentations of the dead are a principal aesthetic instrument in Korea’s “rituals of resistance.”[13] The voices of the dead are considered both as evidence of political violence and as an appeal for collective actions for justice. Political activism in South Korea is so intimately tied to the ritual aesthetics of lamenting spirits of the dead that even an academic forum may not dispense with the aesthetic form. When the annual conference of Korean anthropologists chose the cultural legacy of the Korean War as its main theme in 1999, the conference included a grand shamanic spirit consolation rite dedicated to all the spirits of the tragic dead from the war era. In these situations, the history of mass war death is not merely an object of academic debate or collective social actions, but takes on a vital agency of a particular kind that influences the course of communicative actions about the past.

In Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche wrote, “A thought comes when “it” wants to and not when “I” want; thus it is a falsification to say: the subject “I” is the condition for the predicate “think.” It thinks: but there is…no immediate certainty that this “it” is just that famous old “I”.”[14] The remembering self’s incomplete autonomy and the remembered other’s incomplete passivity are perhaps implicit in any form of commemoration. The lamentation of the dead is a radical example of this inter-subjective nature of remembrance.

The lamentations of the dead constitute an important aesthetic form in Korea’s culture of political protest, and this should be considered against the nation’s particular historical background; most notably, its experience of the cold war in the form of a violent civil war and the related political history of anti-communism. The proliferation of the spirit narration of violent war death in the present time relates to the repression of the history of mass death in the past decades. The rich literary tradition of Jeju testifies to this intimate relationship between the grievance-expressing spirits of the dead and the inability of the living to account for their memories.

Hyun Gil-eon’s short story Our Grandfather, for instance, tells of a village drama caused by a domestic crisis when a family’s dying grandfather is briefly possessed by the spirit of his dead son. The possessed grandfather suddenly recovers his physical strength and visits an old friend (of the son) in the village. The villager had taken part in accusing the son of being a communist sympathizer during the 4.3 incident, thereby causing his summary execution at the hands of counterinsurgency forces. The grandfather demands that he publicly apologize for his wrongful accusation. The villager refuses to do so and instead gathers other villagers to help in his plot to lynch the accuser. The return of the dead in this magical drama highlights the villagers’ complicity in the unjust death of the son and the long imposition of silence about past grievances. The story’s climax comes when the son’s ghost realizes the futility of his actions and turns silent, at which moment the family’s grandfather passes away.[15]

Just as the silence of the dead was a prime motif in Jeju’s resistance literature under the anticommunist political regimes, so their publicly staged lamentations are now a principal element in the island’s cultural activity after the democratic transition. Between the past and the present, a radical change has taken place in that the living are no longer obliged to play deaf to what the dead have to say about history and historical justice. What is continuous in time, however, is that the understanding of political reality at the grassroots level is expressed through the communicability of historical experience between the living and the dead.

The rituals displaying the lamenting spirits of the dead have become public events in Jeju since the end of the 1980s and were part of the forceful nationwide civil activism in the 1990s. In Jeju, the activism was focused on the moral rehabilitation of the casualties from the 4.3 incident as innocent civilian victims, instead of their previous classification as communist insurgents. The rehabilitative initiatives have since spread to other parts of the country and resulted in the legislation in 2000 of a special parliamentary inquiry into the 4.3 incident. This was followed by legislation passed in May 2005 on the investigation of incidents of Korean War civilian massacres in general. These initiatives led to forensic excavations on a national scale in the subsequent years for suspected sites of mass burial as well as the completion of a memorial park (Jeju 4.3 Peace Park) in Jeju in 2008. The 2005 legislation includes an investigation of the round-up and summary execution of alleged communist sympathizers in the early days of the Korean War, an estimated two to three hundred thousand civilians.[16]

Jeju Peace Park

These dark chapters in modern Korean history were relegated to non-history under the previous military-ruled authoritarian regimes, which defined anti-communism as one of the state’s prime guidelines. Since the early 1990s, in contrast, these hidden histories of mass death have become one of the most heated and contested issues of public debate, and their emergence into public discourse is, in fact, regarded by observers as a key feature of Korea’s political democratization. The province of Jeju is exemplary in terms of this development. It initiated an institutional basis for a sustained documentation program for the victims of the 4.3 atrocities, and province-wide memorial events, it continues to excavate suspected mass burial sites and plans to preserve these sites as historical monuments. The provincial authority also hopes to develop these activities to promote the province’s public image as “an island of peace and human rights.” These laudable initiatives have undergone considerable setback since the current conservative administration in South Korea took power in 2008. The new administration regarded the previous efforts to account for past grievances and historical injustice from a crude economic perspective, defining them as an unproductive activity, and this provoked indignant public reactions in Jeju.

The above achievements of Jeju islanders were made possible by their sustained community-based grassroots mobilization, activated through networks of non-governmental organizations and civil rights associations, including the association of the victims’ families. For those active in the family association, the early 1990s was a time of sea change. Before 1990 the association was officially called the Anti-Communist Association of Families of the Jeju 4.3 Incident Victims and, as such, it was dominated by families related to a particular category of victims – local civil servants and paramilitary personnel killed by the communist militia. This category of victims, in current estimation, amounts to 10 to 20 per cent of the total civilian casualties. The rest were the victims of the actions of government troops, police forces or the paramilitary groups, and previously were classified as communist subversives or “red elements.” Since 1990, the association gradually has been taken over by the families of the majority side, relegating the family representatives from the anticommunist association era to minority status within the association. This was “a quiet revolution,” according to a senior member of the association, a result of a long, heated negotiation between different groups of family representatives.[17]

During the transition from a nominally anticommunist organization to one that intends to “go beyond the blood-drenched division of left and right,” the association faced several crises: some family representatives with anticommunist family backgrounds left the association, and some new representatives with opposite backgrounds refused to sit with the former representatives. Conflicts still exist not only within the provincial-level association, but also at the village level. Nevertheless, the association’s resolute stand that its objective is to account for all atrocities from all sides, communist or anticommunist, has been conducive to preventing the conflicts from reaching an explosive level. Equally important was the fact that many family representatives (particularly from the villages in the mountain region, which suffered both from the pacification activity of the government troops and from the retributive actions from the communist partisan groups) had casualties on both sides of the conflict within their immediate circle of relatives. The democratization of the family association was a liberating experience for the families on the majority side, including those who were members of it before the change. Under the old scheme, some of the victims of the state’s anticommunist terror were registered as victims of the terror perpetrated by communist insurgents. This was partly a survival strategy of the victims’ families and was partly caused by the prevailing notion that the “red hunt” campaign would not have happened had there been no “red menace.” The “quiet revolution” of the 1990s meant that these families are now free to grieve for their dead relatives of 1948 publicly and without falsifying the history of their mass death.

The above development has affected the islanders’ ritual commemorative activities. As previously noted, earlier works on this issue emphasized the relevance of shamanic rituals in the politics of memory. It has been argued that the shamanic rituals are relatively open to the intrusive actions of politically troubled ancestral spirits, thus giving the latter an opportunity to express their grievances about their violent historical experience – an opportunity unavailable in ancestral rites.[18] These works describe communal ancestral rituals as having been under the grip of the state’s anticommunist policies, whereas shamanic rituals are considered to have been relatively free from political forces. This changed in the 1990s. Many communities in Jeju have recently begun to introduce previously outlawed “red” ancestral identities into their communal ancestral rituals, thereby placing their memorabilia in demonstrative coexistence with the tablets of other “ordinary” ancestors, including the memorabilia of patriotic “anticommunist” ancestors.

The last process has resulted in the rise of diverse, highly inventive new communal ancestral shrines across communities in Jeju and elsewhere in South Korea. One of them is the monument in the village of Hagui, in the northern district of Jeju island, completed in the beginning of 2003. In the white stone at the centre of the picture is inscribed, in Chinese characters, “Shrine of spirit consolation.” The two black stones on the left commemorate the patriotic ancestors from the colonial era, the patriotic fighters from the village during the Korean War and, later, from the military expedition to the Vietnam War. The two black stones on the right side commemorate the hundreds of villagers who fell victim to the protracted anticommunist counterinsurgency campaigns waged in Jeju before and during the Korean War.

New Communal Ancestral Shrine, Hagui

The completion of this village ancestral shrine has a complex historical background. An important factor was the division of the village into two separate administrative units in the 1920s, which the locals understand now to have been a divide-and-rule strategy of the Japanese colonial administration at the time, and the distortion of this division during the chaos following the 4.3 uprising. Hagui elders recall that the village’s enforced administrative division developed into a perilous, painful situation at the height of the counterinsurgency military campaigns. The logic of these campaigns set people in one part of the village, labeled then as a “red” hamlet, against those in the other, who then tried to dissociate themselves from the former. After these campaigns were over, Hagui was considered a politically impure, subversive place in Jeju (just as the whole island of Jeju was known as a “red” island to mainland South Koreans). Villagers seeking employment outside the village experienced discrimination because of their place of origin, and this aggravated the existing grievances between the two administratively separate residential clusters. People of one side felt it unjust that they were blamed for what they believed the other side of the village was responsible for; and the latter found it hard to accept that they should endure accusations and discrimination even within a close community. It was against this background that a group of Hagui villagers petitioned the local court to give new, separate names to the two village units. Their intention was partly to bury the stigmatizing name of Hagui, and also to eradicate signs of affinity between the two units. This was just after the end of the Korean War in 1953. Since then, the village of Hagui was separated in official documents into Dong-gui and Gui-il, two invented names that no one liked but which were, nevertheless, necessary.

The above historical trajectory resulted in a host of problems and conflicts in the villagers’ everyday lives. Not only did a number of them suffer from the extra-judicial system of collective responsibility, which prevented individuals with an allegedly politically impure family and genealogical background from taking employment in public sectors or from enjoying social mobility in general; but some of them also had to endure sharing the village’s communal space with someone who was, in their view, culpable for their predicament. This last point relates to the enduring wounds of the 4.3 history within the community, caused by the villagers’ complex experience with the government’s counterinsurgency actions and the retributive violence perpetrated by the insurgents. These included, as shown in the story of Our Grandfather, being coerced into accusing neighbors of supporting the enemy side. These hidden histories are occasionally pried open to become an explosive issue in the community, as when, for instance, two young lovers protest against their families’ and the village elders’ fierce opposition to their relationship, without giving them any intelligible reason for doing so.

The details of these intimate histories of the 4.3 violence and their contemporary traces remain a taboo subject in Hagui. The most frequently recalled and excitedly recited episodes are instead related to festive occasions. Some time before the villagers began to discuss the idea of a communal shrine, the two units of Hagui joined in an inter-village sporting event and feast organized periodically by the district authority. They had done so on many previous occasions, but this time, the two football teams of Dong-gui and Gui-il both managed to reach the semi-final, each hoping to win the championship. During the competition, the residents of Dong-gui cheered against the team representing Gui-il, supporting the team’s opponent from another village instead, and the same happened with the residents of Gui-il in a match involving the team from Dong-gui. This experience was scandalous, according to the Hagui elders I spoke to, and they contrasted the divisive situation of the village with an opposite initiative taking place in the wider world. (At the time of the inter-village feast, the idea of joint national representation in international sporting events was under discussion between South and North Korea.) The village was going against the stream of history, according to the elders, and they said that the village’s shameful collective representation on the district football ground provided the momentum for thinking about a communal project that would help to reunite the community of Hagui.

In 1990, the village assemblies in Dong-gui and Gui-il each agreed to revive their original common name and to shake off their separation of the four decades since the Korean War. They established an informal committee responsible for the rapprochement and reintegration of the two villages. In 2000, this Committee for Village Development proposed to the village assemblies the idea of erecting a new ancestral shrine based on contributions from the villagers and from those living elsewhere. The idea attracted a broad support from the villagers including those who came to settle in the village in recent years. It also received strong endorsement from the village elders’ associations; among the most enthusiastic supporters was the elder who had joined the partisan group as a boy and whose elder brother had been killed by the insurgents. The donations to the project came from many elderly widows, who had lost their husbands to the counterinsurgency violence during the 4.3 chaos, as well as from a successful businessman settled in Seoul, the eldest son of a villager killed by the insurgents. When the shrine was completed in 2003, the Hagui villagers held a grand opening ceremony in the presence of many visitors from elsewhere in the country and from overseas (many from Hagui live in Japan). The black memorial stones on the left (from the spectator’s perspective) are inscribed with names of patriotic village ancestors, including one hundred names from colonial times, dozens of patriotic soldiers from the Korean War or the Vietnam War, and a dozen villagers killed by communist partisans during the 4.3 chaos. The one hundred patriotic ancestors from the colonial era include a few persons whose dedication to the cause of national liberation was combined with a commitment to socialist or communist ideals. The merit of these so-called left-wing nationalists was not recognized before the 1990s.[19] The twelve villagers killed by the insurgents belonged to the village’s civil defense groups hastily organized by the South Korean counterinsurgency police forces. Most of them were not equipped with firearms and had been forcibly recruited to the role. Whether to place the names of these twelve individuals on the side of patriotic ancestors or that of tragic mass death was one of the most difficult, contested questions during the three-year preparation for the shrine.

Two stones on the left

The two stones on the right commemorate 303 village victims of the anticommunist political terror during the 4.3 incident, and dedicate the following poetic message to the victims:

When we were still enjoying the happiness of being freed from colonial misery,

When we were yet unaware of the pains to be brought by the Korean War,

The dark clouds of history came to us, whose origin we still do not know after all these years.

Then, many lives, so many lives, were broken and their bodies were discarded to the mountains, the fields and the sea.

Who can identify in this mass of broken lives a death that was not tragic?

Who can say in this mass of displaced souls some souls have more grievances than others?

What about those who could not even cry for the dead?

Who will console their hearts that suffered all those years only for one reason that they belonged to the bodies who survived the destruction? …

For the past fifty years,

The dead and the living alike led an unnatural life as wandering souls, without a place to anchor.

Only today,

Being older than our fathers and more aged than our mothers,

We are gathered together in this very place.

Let the heavens deal with the question of fate.

Let history deal with its own portion of culpability.

Our intention is not to dig again into the troubled grave of pain.

It is only to fulfill the obligation of the living to offer a shovel of fine soil to the grave.

Our hope is that some day the bleeding wounds may start to heal and we may see some sign of new life …

Looking back, we see that we are all victims.

Looking back, we see that we are all to forgive each other.

In this spirit, we are all together erecting this stone.

For the dead, may this stone help them finally close their eyes.

For us the living, may this stone help us finally hold hands together.[20]

Two stones on the right

The democratization of kinship relations is at the heart of political development beyond the polarities of left and right. This is not merely because family and kinship are elementary constituents of civil society as Giddens describes it, but primarily because kinship has actually been a locus of radical, violent political conflicts in the past century, which, by extension, means that social actions taking place in this intimate sphere of life are important for shaping and envisioning the horizon beyond the politics of the cold war.

The end of the cold war as the dominant geopolitical paradigm of the past century has enabled people to publicly recount their lived experience of bipolar conflict without fearing the consequences of doing so, and it also has encouraged many scholars of cold war history to turn their attention from diplomatic history to social history. These two developments are interconnected and together constitute the now emerging field of social and cultural histories of the cold war. In societies that experienced the cold war in the form of a vicious civil war, recent research shows how the violently divisive historical experience continues to influence interpersonal relations and communal lives.[21] The reconciliation of ideologically bifurcated genealogical backgrounds or ancestral heritages (“red” communists versus anticommunist patriots or, in other contexts, revolutionary patriots versus anticommunist “counter-revolutionaries”) is a critical issue for individuals and for the political community.[22] In these societies, kinship identity, broadly defined inclusive of place-based ties, is a significant site of memory of past political conflicts, and also can be a locus of creative moral practices.

The experience of the cold war as a violent civil conflict resulted in political crisis in the moral community of kinship. It resulted in a situation that Hegel characterizes as the collision between “the law of kinship,” which obliges the living to remember their dead kinsmen, and “the law of the state,” which forbids citizens from commemorating those who died as enemies of the state. The political crisis was basically a representational crisis in social memory, in which a large number of family-ancestral identities were relegated to the status that I have elsewhere called “political ghosts,” whose historical existence is felt in intimate social life, but is nevertheless traceless in public memory.

Hegel explored the philosophical foundation of the modern state partly with ethical questions involved in the remembrance of the war dead, drawing upon the legend of Antigone from the Theban plays of Sophocles. Antigone was torn between the obligation to bury her war-dead brothers according to “the divine law” of kinship on one hand and, on the other, the reality of “the human law” of the state, which prohibited her from giving burial to enemies of the city-state.[24] She buried her brother, who died as the hero of the city, and then proceeded to do the same for another brother, who died as an enemy of the city. The latter act violated the edict of the city’s ruler, and she was condemned to death as punishment. Invoking this epic tragedy from ancient Greece, Hegel reasoned that the ethical foundation of the modern state is grounded in a dialectical resolution of the clashes between the law of the state and the law of kinship. For Judith Butler, the question pivots on the fate of human relatedness suspended between life and death and forced into the tortuous condition of having to choose between the norms of kinship and subjection to the state.[25]

The epic heroine Antigone met death by choosing family law over the state’s edict; survival, for many families in post-war South Korea, meant following the state’s imperative to sacrifice their rights to grieve properly and seek consolation for the death of their kinsmen. The state’s repression of the right to grieve was conditioned by the wider politics of the cold war. Emerging from colonial occupation only to be divided into two hostile states, the new state of South Korea found its legitimacy partly in the performance of anticommunist containment. Its militant anticommunist policies included making a pure ideological breed and denying impure traditional ties. Sharing blood relations with an individual believed to harbor sympathy for the opposite side of the bipolar world, in this context, meant being an enemy of the political community. Left or right in this political history was not merely about bodies of ideas in dispute, but also about determining the bodily existence of individuals and collectives. Likewise, the process “beyond left and right” in this society has to deal with corporeal identity. If someone has become an outlawed person by sharing blood ties with the state’s object of containment and exclusion, that person’s claim to the lawful status of a citizen requires legitimizing this relatedness. This is how kinship emerges as a locus of the decomposing bipolar world in the world’s outposts, and as a powerful force in the making of a tolerant, democratic society.

Giddens writes: “If there is a crisis of liberal democracy today, it is not, as half a century ago, because it is threatened by hostile rivals, but on the contrary because it has no rivals. With the passing of the bipolar era, most states have no clear-cut enemies. States facing dangers rather than enemies have to look for sources of legitimacy different from those in the past.”[26] He then proceeds to chart what he considers to be the new sources of state legitimacy, for which he highlights the political responsibility to foster an active civil society, that is, to further democratize democracy. In this light, Giddens paints the form of the democratic family as the backbone of active civil society after the cold war. As a new social form, the democratic family is meant to structurally reconcile individual choice and social solidarity, and to achieve a dialectical resolution between individual freedom and collective unity.

In Giddens’ scheme, the social form of kinship has no direct association with the oppositions of left and right. Its role for societal development beyond the cold war is mediated by the state’s changing identity and the related reconfiguration of its relationship to civil society. The end of the cold war, for Giddens, primarily affects the state, in the sense of losing the legitimacy of prioritizing external threats. The displacement of the state from the dualist geopolitical structure forces the state to build alternative legitimacy in an active, constructive engagement with civil society. The challenge is to forge a constructive internal relationship with society in place of hostile external relationships with other states. The idea of the “democratic family” enters this picture as a constitutive element of civil society, that is, as an important site of post-cold war state politics.

The composition of “new kinship” presented by Giddens, however, allows little space for kinship practices that arise from the background of a violent modern history such as Jeju’s. His account of right and left unfolds as if this political antithesis had principally been an issue of academic paradigms or parliamentary organizations, without mass human suffering and displacement. Giddens discusses social and political developments beyond left and right on the assumption that the end of the cold war is coeval with the advance of globalization and that these two changes constitute what he sees as “the emergence of a post-traditional social order.”[27] If the end of the cold war is at the same time an age of globalization, as Giddens claims, and the third way vision speaks of the morality and politics of this age, it is puzzling why this vision, claiming to speak for the global age, draws narrowly on the particular history of the cold war manifested as a contest and balance of power, ignoring the war’s radically diverse ramifications across different places. Moreover, Giddens blames Hegel for advancing a teleological concept of history, which he believes was sublimated in cold war modernity.[28] From his history of left and right, it transpires that, for him, Hegelian historicism is one of the notable philosophic ills that nations and communities should be alert to in pursuing a progression away from the age of extremes toward a relationally cosmopolitan and structurally democratic political and social order. This essay argues to the contrary – that Hegelian political ethical questions are crucial for historical progression away from the age of violent bipolar politics.

The world did not experience the global cold war in the same way or remembers it now in an identical way. It is true that the period of the cold war was a “long peace” – the idiom with which the historian John Lewis Gaddis characterizes the international environment in the second half of the twentieth century, partly in contrast to the war-tone era of the first half.[29] Gaddis believes that the bipolar structure of the world order, despite the many anomalies and negative effects it generated, contributed to containing an overt armed confrontation among industrial powers. As Walter LaFeber notes, however, this view of the cold war speaks of a half-truth of bipolar history.[30] The view represents the dominant Western (and also the Soviet) experience of the cold war as an imaginary war, referring to the politics of competitively preparing for war in the hope of avoiding an actual outbreak of war, whereas identifying the second half of the twentieth century as an exceptionally long period of international peace would be hardly intelligible to much of the rest of the world. The cold war era resulted in forty million human casualties of war in different parts of the world as LaFeber mentions,[31] how to reconcile this exceptionally violent historical reality with the predominant Western perception of an exceptionally long peace is a crucial question for comparative history and for grasping the meaning of the global cold war.

Seen in a wider context, therefore, we cannot think of the history of right and left without confronting the history of mass death. Right and left were both part of anti-colonial nationalism, signaling different routes toward the ideal of national liberation and self-determination. In the ensuing bipolar era, this dichotomy was transformed into the ideology of civil strife and war, in which achieving national unity became equivalent to annihilating one or the other side from the body politic. In this context the political history of right and left is not to be considered separately from the history of the human lives and social institutions torn by it, nor is the “new kinship” after the cold war to be divorced from the memory of the dead ruins of this history. Family relations are important vectors in understanding the decomposition of the bipolar world. This is not merely because they are an elementary constituent of civil society, as Giddens believes, but above all because they have actually been a vital site of political control and ideological oppression during the cold war. Seen against this historical background, it is misleading to define the state in the post-cold war world merely as an entity without external enemies. Rather, we have to think of the state, as Hegel did, as an entity that has to deal with internal hostilities and reconciliation with society, a significant part of which the state condemned to an unlawful status. What has happened in Jeju since the early 1990s can be placed along this hopeful trajectory of reconciliation, and the recognition of the rights to remember and console the dead has been a central element in this important social progress beyond left and right.

Lanterns to the Dead

Heonik Kwon teaches anthropology at the London School of Economics and is an Asia-Pacific Journal associate. He is the author of After the Massacre: Commemoration and Consolation in Ha My and My Lai, which received the inaugural Clifford Geertz prize from the American Anthropological Association. His Ghosts of War in Vietnam, was awarded the first George Kahin prize by the Association for Asian Studies in 2009. A shorter, earlier version of this article was published in The Korea Yearbook 2007 (Leiden: Brill, 2008).

Recommended citation: Heonik Kwon, “Healing the Wounds of War: New Ancestral Shrines in Korea,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 24-4-09, June 15, 2009.

Notes

The research for this article is part of a more extensive research on the commemoration of the Korean War, supported by the Academy of Korean Studies research grant (AKS-2007-R20) and by the British Academy research development award (BARDA-48932).

[1] Yun, Taik-Lim (2003), Inlyuhakja_i gwagŏyŏhaeng: han ppalgaengi ma_l_i yŏksarŭl ch’atasŏ [An anthropologist’s journey to the past: in search of history in a “red” village], Seoul: Yŏksabipyŏngsa, pp. 148-52.

[2] In this article the idea of “global cold war” is used deliberately, in distinction to that of the ‘cold war’. The term “cold war” refers to the prevailing condition of the world in the second half of the 20th century, divided as it was into two separate paths of political modernity and economic development. In a narrower sense it means the contest of power and will between the two dominant states, the United States and the Soviet Union, which (according to George Orwell, who coined the term in 1945) set out to rule the world between them under an undeclared state of war, being unable to conquer one another. In a wide definition, however, the global cold war also entails the unequal relations of power among the political communities, which pursued or were driven to pursue a specific path of progress within the binary structure of the global order. The cold war’s former dimension of a contest of power has been an explicit and central element in cold war historiography; the more recent aspect of a relation of domination is a relatively marginal and implicit element. This duplicity of bipolar political history relates closely to the definitional problem inherent in the reference of the cold war, which contracts the violent experience of political bipolarity endured in many non-Western regions. Following Westad, I use the term “global cold war” as a reference that incorporates both of these two analytical dimensions. See Westad, Odd Arne (2005), The Global Cold War: Third World Interventions and the Making of Our Times, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

[3] Despite South Korea’s appearance of being a highly industrialized and urbanized modern society, as observers note, political relations actually have strong elements of a traditional agrarian society, where public life and political association rely heavily on existing solidary relations based on a common place of origin or lineage identity, including close interpersonal ties traced to common educational backgrounds. Traditional social identities continue to matter in Korean public culture, and this applies to the process of democratization. See Kim, Kwang-Ok (2000), “Jŏnt’ongjŏk ‘gwankye’ŭi hyŏndaejŏk silch’ŏn” [The contemporary practice of ‘traditional’ relations], in Hankuk Munhwa Inlyuhak [Journal of Korean cultural anthropology], 33 (2), pp. 7-48.

[4] Park, Myong-Lim (1999), “Minjujuŭi, isŏng, gŭrigo yŏksayŏngu: Jeju 4.3gwa hankuk hy_ndaesa” [Democracy, rationality and historical research: the Jeju 4.3 incident and modern Korean history], in Jeju 4.3 je 50junyŏn Ginyŏmsaŏp Ch`ujin Bŏmkukminwiwŏnhoe [The National Committee for the 50th Anniversary of the Jeju 4.3 Incident] (eds), Jeju 4.3 Yŏnku [Jeju 4.3 studies] Seoul: Yŏksabipyŏngsa, pp. 425-60.

[5] Giddens, Anthony (1998), The Third Way: Renewal of Social Democracy, Cambridge: Polity Press, pp. 90-93.

[6] Giddens, Anthony (1994), Beyond Left and Right: The Future of Radical Politics, Cambridge: Polity Press, p. 13.

[7] Ibid., p. 14.

[8] Bobbio, Norberto (trans. Allan Cameron) (1996), Left and Right: The Significance of a Political Distinction, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, p. 14.

[9] Cumings, Bruce (1991), Parallax Visions: Making Sense of American-East Asian Relations at the End of the Century, Durham NC: Duke University Press, p. 51.

[10] Kim, Seong-Nae (1989), “Lamentations of the Dead: Historical Imagery of Violence,” Journal of Ritual Studies 3 (2), pp. 251-85.

[11] Kwon, Heonik (2004), “The Wealth of Han,” in M. Demeuldre (ed.), Sentiments doux-amers dans les musiques du monde, Paris: L’Harmattan, pp. 47-55.

[12] Kim, Kwang-Ok (1994), “Rituals of Resistance: The Manipulation of Shamanism in Contemporary Korea,” in C. F. Keys, L. Kendall, and H. Hardacre (eds), Asian Visions of Authority: Religion of the Modern States of East and Southeast Asia, Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, pp. 195-221.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Cited from Bettelheim, Bruno (1985), Freud and Man’s Soul: An Important Re-interpretation of Freudian Theory, London: Fontana Bettelheim, p. 61.

[15] Hyun, Gil-Eon (1990), Uridŭlŭi jobunim [Our grandfather], Seoul: Koryŏwŏn.

[16] See the activity of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Republic of Korea, available here, and also here.

[17] Interview with Mr. Kim Du-Yon in Jeju City, South Korea, January 2007.

[18] Kim Seong-Nae, “Lamentations of the Dead”; see also Janelli, Roger L. and Dawnhee Yim Janelli (1982), Ancestor Worship and Korean Society, Stanford: Stanford University Press, pp. 151-67.

[19] The South Korean administration has recently begun to nominate some of these “leftist” anti-colonial activists and intellectuals as national heroes. The rewriting of Korea’s history of independence movements or nationalist movements in a more inclusive form that recognizes the heritage of radical as well as moderate nationalist movements, which is quite active today among historians in South Korea, has had a positive influence on the development of local initiatives for political reconciliation, including those in Hagui.

[20] A full text of this poem in Korean is available online here.

[21] See Mazower, Mark (ed.) (2000), After the War Was Over: Reconstructing the Family, Nation, and State in Greece, 1943-1960, Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press; Tai, Hue-Tam Ho (ed.) (2002), The Country of Memory: Remaking the Past in Late Socialist Vietnam, Berkeley: University of California Press.

[22] Kwon, Heonik, (2006), After the Massacre: Commemoration and Consolation in Ha My and My Lai, Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 154-64.)

[23] See the Japan Focus article available here.

[24] Stern, Steve (2002), Hegel and the Phenomenology of Spirit, New York: Routledge, p. 140.

[25] Butler, Judith (2000), Antigone’s Claim: Kinship Between Life and Death, New York: Columbia University Press, p. 5.

[26] Giddens, The Third Way, pp. 70-71.

[27] Giddens, Beyond Left and Right, p. 5.

[28] Ibid., pp. 53-9, 252.

[29] Gaddis, John Lewis, The Long Peace: Inquiries into the History of the Cold War, New York: Oxford University Press, 1987.

[30] LaFeber, Walter, “An End to Which Cold War?” in M. J. Hogan (ed.) The End of the Cold War: Its Meaning and Implications, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1992, pp. 13-4.

[31] Ibid., 13.