Why a Boom in Proletarian Literature in Japan? The Kobayashi Takiji Memorial and The Factory Ship

Heather Bowen-Struyk

In February 2009, I was in a book store in the international terminal of Tokyo’s Narita Airport when I saw it: Kobayashi Takiji’s 1929 novella Kani Kosen (The Factory Ship) on the endcap sporting the best-sellers of 2008.

Kani kosen, #13 best-seller of 2008 in Tsutaya bookstore in the international terminal of Tokyo Narita airport

Two young Japanese women paused near the endcap, and then one picked up the book. I asked them why they were interested in it, explaining that I research Japanese proletarian literature. One woman cautiously answered, “Kani kosen has been discussed a lot lately.” Neither woman had read it, nor did they buy it then.

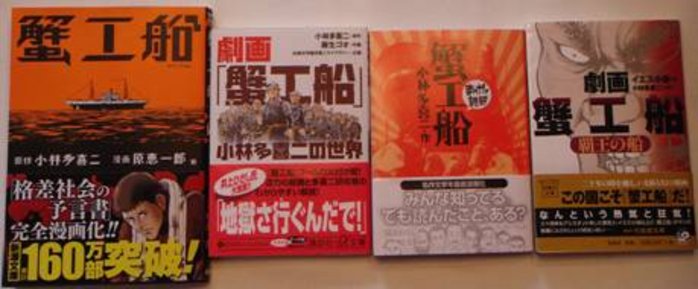

“Discussed a lot lately.” To the surprise of many, circulation of the nearly 80 year old proletarian novella Kani kosen jumped from approximately 5,000 copies per year to over 500,000 in 2008, and that does not include sales of the four manga versions which may have reached many more readers.

Four manga versions of Kani kosen

By the fall of 2008, the “Kani kosen boom”—as it is called—was being discussed everywhere, from women’s fashion magazines to Playboy, television news, general circulation journals and the blogosphere.[1] Norma Field has described the development of the boom in greater detail including the tremendous efforts and bankrolling of an unlikely supporter, the community of scholars who rose to the challenge, as well as the economic meltdown, the serendipity of brick and mortar book stores and the involvement of a new species of public intellectual in the recasting of Kobayashi Takiji’s legacy: to sum up, she describes it as “a miraculous meeting of pure contingency and absolute necessity, of commercial appetite and human need.”[2] New phrases have been coined, including a verb “kani ko suru (to do degrading labor) and the lamentation “kore ja maru de kani ko da naa!” (this is just like Kani Kosen!). In May and June of 2009, two stage adaptations were produced in Tokyo, and in the summer of 2009, blockbuster director SABU is set to release a major motion picture.[3] Media reactions have ranged from astonishment that an old book by a Communist writer would become a best-seller to optimism that the generation of young people best known as the “lost generation” is finally (maybe) ready to engage politically.

Faced with uncertain economic growth since the bursting of the economic bubble in 1991, an entire generation has now grown up without the sureties experienced by their parents. And 2008, which was a bad year for capitalism everywhere, was especially bad in Japan.[4] Temp agencies (haken gaisha) have become the artificial respirator on a critically wounded system, providing the labor-lifeblood to the corporate world and keeping just enough people employed to prevent a cardiac arrest. “Working poor” (wakingu pu-a), “divided society” (kakusa shakai) and “precariat” (a neologism combining “proletariat” and “precarious”)—buzzwords of the last year or two—give linguistic form to the experience of economic despair. The Akutagawa prize-winning novella on the newsstands in February, “Boats of Pothos Lime,” about a wrist-cutting young woman who works three part-time jobs and dreams of an extravagantly priced vacation, was hailed as “literature of the ‘temp generation.’”[5] How expensive, I found myself wondering, was the vacation that the two young women in the international terminal were taking? And what was the relationship between their international travel and their interest (and ultimately, disinterest) in Kani kosen?

Takiji (1903-1933), as he is called by his admirers, participated in the proletarian literature movement as an author, activist and member of the then illegal Communist Party until he was tortured to death while under interrogation by the special higher police on February 20, 1933. He was 29 years old.

Kobayashi Takiji (1903-1933)

For nearly a decade in prewar Japan, proletarian writers offered the most sustained critiques of Japanese imperialism, its relationship to capitalism, the complicity of the apparatuses of the state, and the unequal burden borne by the laboring masses. Kani kosen (1929) brings these issues to life aboard a crab-cannery boat fishing the contested waters between Japan and Russia.

I wanted to know more about the Kani kosen boom and the legacy of this proletarian writer, so when I found myself invited to a Takiji commemorative event on the anniversary of his death on February 20, I accompanied Norma Field, who had just published a book in Japanese on Takiji, on a trip to snowy Otaru in Hokkaido.[6] I asked a lot of questions. More than anything, I really wanted to know about young people: were they really reading Kani kosen? What did they think? Was this just a fad or something else? That, of course, was why I approached the young women in the airport. And as you can see from that anecdote, I did not get the answers I was looking for. But learning happens in unexpected ways, and this report is the result of what I learned. I walked the snowy—sometimes blizzardy—ground of Otaru, where Takiji lived from the age of 4 until he left for Tokyo as a young man, to learn more about the conditions that shaped a young activist-writer. I attended two memorial services in Otaru: one, held at his grave during the day; and the other, an evening event that filled a 450 person hall. And I listened. Following is my report, with three parts of my amateur documentary embedded: Part One: Takiji’s Life in Otaru; Part Two: The Graveside Ceremony; and Part Three: The Meaning of the Boom.

Takiji’s Life in Otaru

On the ground in Otaru, an industrial port city in Hokkaido, I confronted the reality that the Kani kosen boom has not yet manifested itself in a vibrant youth culture of protest, but it has brought a tangible excitement to the city that boasts Takiji’s grave and has a compelling claim to be his hometown. Just as with other authors, there are books that describe Takiji “literary walks” for fans to retrace places of significance to the author. But now, as a result of the boom, there is also a JTB (Japan Tourist Bureau) bus tour which I signed on to with Norma.

Takiji literary tour bus in front of a sign announcing the evening Takiji Memorial event

The tour starts at the Otaru Literary Museum, a museum that features Takiji, Ito Sei (1905-1969), Oguma Hideo (1904-1940) and several others. The curator Tamagawa Kaoru, also our guide for the tour, tells me that the museum has had a bump in attendance from the boom, but he describes the typical visitor as one who is intimidated by Takiji’s lifestyle—this does not sound like a breeding ground for activism. The pink bus picks us up at the museum, takes us around Otaru, and makes a special visit to the gravesite. There were about a dozen of us, and I was the only person under the age of 40.

How did Takiji come to be a proletarian writer and activist? Takiji’s family moved to Otaru when he was 4 years old. As Norma Field explains, Otaru was a semi-colonial frontier which represented opportunity for Takiji’s impoverished family, and with the financial assistance of an entrepreneurial uncle, Takiji received an excellent education at the liberal Otaru Commercial Higher School (now the Otaru Commercial University). After graduation, he got a good job at the Hokkaido Colonial Bank on the “wall street” of Otaru. It was then that he began dating Taguchi Taki, a woman employed in the nebulous margins of the sex industry, who became a model for some of his early fiction describing the suffering of women and children. It was also while he was employed at the bank that he published some of his most famous works including “March 15, 1928” (1928), Kani kosen (1929), “The Factory Cell” (1930) and “The Absentee Landlord” (1930)—this last work led to his being fired when he directly implicated his bank in the problem of absentee landlordism.

Most rewarding for me, I hiked the steep snowy streets—radiating up from the port set in a crater—guided by Norma and others very knowledgeable about Takiji. We visited the site of his former home down by the port, walked up the long steep hill called “hell hill” (you’ll have to watch the documentary, below, to get the explanation) to his alma mater with a gorgeous view of the harbor; we visited the former Hokkaido Colonial Bank (now a boutique hotel and chocolatier) in close proximity to the old canal with its picturesque 100 year old warehouses (now more vital to tourism than commerce); we climbed to a mountain shrine in a blizzard where he is said to have snuck away to meet his girlfriend; we toured the working class neighborhood of Temiya and visited the site of thelargest May Day demonstration north of Tokyo in 1927; we visited the Hokkai Seikan Factory (site of “The Factory Cell”) and walked past the police station, made infamous by the description of torture of those arrested in the mass arrests of March 15, 1928.

Takiji’s bronze death mask, in the Otaru Literary Museum. A sign reads: It is ok to touch.

Takiji’s move to Tokyo in 1930 led him deeper into the precarious life of a revolutionary, but clearly he learned to see and articulate the problems with capitalism through his experience growing up in Otaru:

Takiji Memorials

In 2009, there were some twenty Takiji Sai (Takiji Memorials or Takiji Festivals) throughout Japan around the February 20 anniversary of his death. These can be quite big affairs requiring a corresponding network of people who organize and attend them. The larger Takiji Sai tend to be in locales that were important to Takiji’s life like Otaru, Akita, and the Greater Tokyo Suginami-Nakano-Shibuya Memorials, but there is an increasing trend to hold Takiji Sai in other places as well, as in Osaka.[7] Takiji Sai are evening events, and in the tradition of evening proletarian events dating from the 1920s, they feature a musical program as well as a talk or two on Takiji’s life and works. The Takiji Sai event I participated in at Otaru featured a soprano, Murasaki, singing an original piece she composed for Takiji and a keynote speech by Otaru-born and raised Hamabayashi Masao, a prolific retired scholar of the revolutionary tradition in England who has published two books on Takiji in the last two years.[8] This evening event drew 450 people, mostly older than 60, apparently drawn by that combination of civic pride and intellectual interest that characterizes that generation.

But it was the daytime graveside ceremony that captured my imagination: because of its uniqueness (as Wada Kimiko said, “There’s only one grave”), because of its picturesque scenery in the snowy mountains, and moreover, because it made real for me the sorrow of Takiji’s death.

Kobayashi family grave

Over one hundred people gathered midday on a workday for commemorative speeches and to honor his grave. Mourners lined up along the snowy steps for a chance to lay a red carnation on the family tombstone while someone played a tinny version of the “Internationale” on a tape recorder. Oishi Hiroko explained the significance of these flowers: red carnations were sent to imprisoned comrades after Takiji’s death to let them know he had died because there was no way to communicate the tragedy in words.

The Meaning of the Kani Kosen Boom

Kani kosen has endured as the exemplar of Japanese proletarian literature for good reasons. After all, 5,000 copies a year for an aging novella is still pretty good, especially when we consider that the word “proletarian” had become an historical artifact during the overlapping decades of the cold war and high economic growth. Not only is it well-written, it also cleverly dramatizes key theoretical and practical concerns of the labor and arts movement in the late 1920s. Proletarian writers vigorously debated the primacy of art vs. politics, the need to popularize the movement, and the question of style: Kani kosen addresses these key issues with intellectual sharpness.

The SS Hakkō Maru, at once a crab fishing boat and a crab canning factory, sails into the dangerous—physically and ideologically—waters between Russia and Japan. Fortunately, so the men think at first, a Japanese navy destroyer lingers on the horizon should there be any trouble. Meanwhile, the fishermen and factory workers suffer mercilessly under the captain. The captain is a villain: he cares more for the catch than for the men, and more than once he puts this priority into practice by killing or letting men die in order to increase productivity.

In the language of its day, Kani kosen exposed the collusion between the imperialist bourgeoisie (Lenin’s finance capital) and the militarist nation-state at the expense of workers, while demonstrating that the only way to change exploitation was through collective organization. The strike appears destined to fail when the destroyer approaches and comes to the aid of the captain, to the surprise of many aboard the ship, but as the strike leaders are led away, the remaining men yell, “One more time!” Victory may be deferred, but it is tantalizingly within reach.

Nevertheless, the meaning of the boom seems different from the work’s enduring meaning as exemplar of proletarian literature. So much of the astonishment and optimism regarding the boom stems from the involvement of young people—much hyped in the media. Many find it promising to think that young people are interested in a work that confronts the dynamics of exploitation with old-fashioned labor organization. Shimamura Teru, Professor at Ferris University in Tokyo, draws a direct line between Takiji and young people today when he points out that a 26 year old Takiji began Kani kosen, published in the first year of the Great Depression, with the line: “We’re on our way to hell, mate!”[9]

For those intimate with Takiji’s writings, this “boom” represents the possibility of change. Ito Mari, with the Article 9 Association Over Hokkaido, plans programming targeted toward getting young people involved in the movement to protect Article 9, the no-war article of the post-war constitution.[10] When asked why the involvement of young people is so important in the assessment of the boom, she responded, “The reality is that so many young people are having trouble finding or keeping a job. The best thing that can happen for them is for a lot of them to read Kani kosen and realize how similar their situation is.” Kato Taichi, children’s book author, is skeptical that young people are really reading Kani kosen (he defines “youth” as those up to 20 years old and the “precariat” as those between 20 and 40 years old). For him, the best thing that can come of the boom is for adults (over 40) to read it and wake up and take responsibility for the mess they have created: “So many [young people] are suffering because they’re poor and each thinks it’s his own fault—90% of them haven’t read Kani kosen. ‘It’s not my fault—it’s the social system or the result of politics.’ How many can step forward and say that? Very, very few. Young people are really suffering. What if just one more adult could say, ‘It’s not your fault…” That is my hope for the Kani kosen boom. ‘It’s not your fault…”

With his restrained optimism, Sato Saburo, former curator of the Takiji Library from 2003-2008 says, “The boom has already peaked, but new readers have gotten something out of it and can create new works… The message is getting out there. It may have the capacity to change the current situation of the ruling Liberal Democratic Party or labor unions. It may not be a new boom, but I think it will continue on.”

In 1929, Kani kosen was censored and banned, and Takiji was arrested for having written the line which a factory worker says that he hopes the Emperor chokes on the crabmeat they are canning. Attempts were made numerous times in the next couple of years to republish, but each time the work was banned. Kani kosen was dangerous. Today? Kani kosen is not banned. In fact, it is included in lists of works of literature with which elite high schoolers should be familiar. Does this mean it is not dangerous? It’s too soon to say. Meanwhile, despite the apparent distance between a 1929 proletarian novella and contemporary society in one of the world’s wealthiest nations, 51% of people responding to a poll in the Mainichi Newspaper in October 17, 2008, replied that they “can relate to Kani kosen;” of those who could relate, 65% explained “because poverty is a social problem.”

Synopsis:

“Takiji Memorial: February 20, 2009” is a three-part documentary tribute to Kobayashi Takiji (1903-1933) produced by Heather Bowen-Struyk. This account is based on a trip to Otaru, Japan with Takiji-specialist Norma Field to commemorate the life, death and legacy of the young proletarian author-activist who was brutally murdered while being interrogated by the Special Higher Police on Februrary 20, 1933. In 2008, Takiji’s nearly 80 year old novella “The Factory Ship” (Kani kosen) became a best-seller (aka the “boom”), pushing Takiji and the legacy of his work back into the media mainstream. Part One is “Takiji’s Life in Otaru;” Part Two is “Takiji’s Gravesite Ceremony;” and Part Three is “The Meaning of the Boom.”

Heather Bowen-Struyk is the guest editor of the Fall 2006 positions: east asia cultures critique special issue, Proletarian Arts in East Asia: Quests for National, Gender, and Class Justice and an Asia-Pacific Journal associate. She wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: Heather Bowen-Struyk, “Why a Boom in Proletarian Literature in Japan? The Kobayashi Takiji Memorial and The Factory Ship” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 26-1-09, June 29, 2009.

See also:

Heather Bowen-Struyk, Proletarian Arts in East Asia

Heather Bowen-Struyk, The Epistemology of Torture: 24 and Japanese Proletarian Literature

Norma Field, Commercial Appetite and Human Need: The Accidental and Fated Revival of Kobayashi Takiji’s Cannery Ship

[1] Sato Saburo maintains an invaluable site in Japanese for anyone interested in Takiji. For his catalogue of discussions of the boom, see here.

[2] Norma Field, “Commercial Appetite and Human Need: The Accidental and Fated Revival of Kobayashi Takiji’s Cannery Ship” The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol. 8-8-09, February 22, 2009.

[3] In May of 2009, a play was produced in Tokyo. Details here.

[4] See the annotated catalogue of essays on The Asia-Pacific Journal: “Financial-Economic Crisis and the Asia Pacific: World Economic and Financial Crisis, Japan and the Asia Pacific”

[5] Tsumura Kikuko, “Boats of Pothos Lime,” Bungei shunju (March 2009): 338-385.

[6] Norma Field, Kobayashi Takiji: 21seiki ni do yomu ka [Reading Kobayashi Takiji for the 21st Century] Iwanami Shinsho: 2009.

[7] See Sato Saburo’s website, for constantly updated information.

[8] Hamabayashi Masao, “Kani kosen” no shakaishi: Kobayashi Takiji to sono jidai [A social history of Cannery Ship: Kobayashi Takiji and his age] Gakuyu no To mosha: 2009; and Hamabayashi Masao, Kobayashi Takiji to sono jidai: kiwameru me [Kobayashi Takij and his era: extreme eyes] Higashi Ginza shuppansha: 2004.

[9] 島村輝講演6/6 名古屋「蟹工船」と青年なぜ読まれる「蟹工船」

http://blog.goo.ne.jp/takiji_2008/e/f1104ed340b07817ca9b24999215c678

[10] http://www.9-jo.jp/