From Trinity to Trinity

Hayashi Kyoko

Translated by Kyoko Selden

After checking them against a list of prize-winning numbers, a family member of tender age handed me my New Year cards, informing me that I had won three sheets of post-office stamps. One of the cards was from Rui. I read it again: “I am leaving the hospital as I reach retirement age; I plan to enjoy the afternoon tea time of life.” “Now I finally know your age. Bravo,” I said. I had said the same thing on first reading the card that New Year’s morning.

I had known her for nearly thirty years, but never knew how old she was. When I asked her which year she had been born in, she had evaded the question with a laugh, mimicking the voice of a little girl: “When I grow up, I want to be like you, big sister.”

Another was a greeting card from a boutique in Kamakura with a message that said, “Happy Millennium!” The third was a New Year’s greeting from Doctor S, who had been bombed at Hiroshima while serving as a military doctor.

His printed card, written in an old-fashioned epistolary style, read:

It is three and eighty years since I was brought into this world. Having lived through the turmoil of the Taishō and Shōwa eras, if questioned as to what I have accomplished, I maintain some modest pride about having tried my utmost to be a doctor who stands on the side of his patients. A hibakusha myself, I have walked Japan and the world pleading for the abolition of nuclear weapons. These efforts were made with the thought that this was my responsibility to those who swallowed their resentment amidst the infernal fire. Physically weakened in recent days, I have been made to realize the severity of life’s slope in one’s eighties. Yet, super powers possessing nuclear weapons act as if the world were their own. As long as I live, I have no alternative but to pass down the realities of the bombing to younger generations. By way of a New Year’s greeting, I humbly ask you to guide my way, lead me by the hand, and lend me your support.

New Year, 2000

This card brought me back to reality from the peaceful sentiments I had felt on reading Rui’s. In it I hear the heavy breathing of one climbing the last stretch of life’s slope and am also made to realize that my own seventieth year is right before my eyes. This is the reality for those who were bombed on August 6th or 9th. Hibakusha now walk toward death with weakened legs and backs. I once announced, when I was still in mid-life, that I would live until I made news: “Today, the last hibakusha died.” But this wish has been unexpectedly hard to fulfill.

Starting last spring, there had been concerns about the impending computer crisis in the year 2000. Stirred by these projections, I stocked up on water and instant noodles. Thinking that I was now ready to survive into the 21st century, my heart felt full.

The year 2000 was namely the 21st century. If so, I should process my August 9th with some finality before the 20th century ended—a century that was on its way out, trailing its power-smoke smeared skirts. Writing a list of those things I had already completed and what I had left undone, I planned a busy schedule for the coming year.

But I had it wrong. “The year 2000 is still the 20th century.” So taught by the young family member, I stopped short for a second. The wrong date imprinted in my memory, however, was hard to erase. “Never mind, let it be wrong,” I thought to myself as I pushed my schedule forward.

The first of the things weighing on my mind was a pilgrimage. This was because Kana and I had made a promise on her 60th birthday that the two of us would some day make a pilgrimage together. But more precisely, I had taken such a journey in the summer of 1998.

Students of the same grade at a girls’ school, we were both bombed during mobilization at the Mitsubishi Armory,1 1.4 kilometers from the epicenter.

The Mitsubishi Steel and Armaments Works

The Mitsubishi Steel and Armaments Works

The primary target for the Nagasaki attack was the Mitsubishi Shipyard, the second being the armory where we had been mobilized to work. The sky over Nagasaki that day was covered with thick clouds, so the shipyard was not visible from Bock’s Car.2 From a rift barely appearing between clouds, the armory showed, and the a-bomb was released. Kana, in a different work area from mine, sustained a heavy injury to her head, which cracked under a falling iron weight. Pulling out a bottle of alcohol from her first-aid bag, she sprinkled the contents on her open wound. The amount of blood doubled and streamed into her eyes and mouth. “I ran from the place, covering the wound with my hand,” she told me.

Since then, whenever August 9th approached, she confined herself in the dark with rain shutters closed, in her camellia-surrounded house on an island to the south of the city. Because she repeated this every year, we simply waited for an autumn day when she would return to a more normal frame of mind. In January of that year, however, she suddenly cut off communication. She left, without telling anyone her destination.

Rumor reached me that she was ill, but no details were available. In order to fulfill our promise, I decided to make the pilgrimage myself. Properly, it should be a tour of the eighty-eight amulet-issuing temples in Shikoku. Yet, although still some years away from reaching Doctor S’s age, I lacked the confidence to walk the entire distance of the Shikoku pilgrimage route, which included many precipitous mountain trails. Cutting the route short to thirty-three temples, I toured the Kannon images on the peninsula where I live. Putting the furoshiki hand cloth Kana had given me the day of her recital in my rucksack,3 I toured the temples along the coast, collecting vermilion stamps on the cloth at amulet offices.

The 88 temple pilgrimage route

The 88 temple pilgrimage route

The cloth, dyed red with the stamps from the thirty-three temples, is still displayed in the miniature family temple at my house. Once the summer had passed, the grease of the red ink started running into the texture of the white background of the cloth, giving off a damp smell. I should give it to Kana before mildew forms, but I still don’t know her whereabouts.

I stopped looking for her, however. Many of the New Year’s cards I received from friends this year bore messages that declined to remain in touch: “Having reached age seventy, this will be the last New Year’s greeting I will send.” This, I gathered, meant leaving future greetings for the other world.

There was one other thing that I had left undone and had to take care of: going to Trinity. The Trinity Site of the Manhattan Project is where the U.S. conducted the first atomic test explosion on earth. At that time, the U.S. possessed the only three a-bombs in existence. One was the uranium bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima. The remaining two were plutonium bombs, one of which was used for the test. The other was dropped on Nagasaki.

When I told Rui that I was visiting Trinity, she asked smoothly, “Are you an a-bomb maniac?” “I wonder,” I answered with a wry smile. Even now I still wish to cut my ties to August 9th. When I wake on certain mornings, I find saliva dyed pink with blood that has oozed from my gums while I sleep. Each time this happens this thought is renewed.

I first traveled to the U.S. in 1985 to join my son Kei during his three-year stay there for a job. Having begun his American life one step ahead of me, he met me when I arrived and drove me on the highway that ran along the Potomac River. It was June, when dogwoods had finished blossoming and the young leaves of Virginia lent their green hue to the sunlight. Perhaps in a regatta practice, a slim-bodied boat went down the brown stream of the river. From the tall maple trees canopying above us, silver-winged seeds fluttered down, shining, onto the water.

In the sky and on the road ahead, too, silver wings flurried.

It was then. The thought suddenly occurred to me that if I pulled the road in toward me, hand over hand, I would come upon the a-bomb test site. Before leaving Japan, I had received an accusing letter from Instructor I from N Girls’ Higher School:4 “The U.S. is the country that dropped the a-bomb on us; have you forgotten that you are a hibakusha?” Following August 9th, in the schoolyard, this teacher had burned the bodies of many students who had died by the bomb, students whose parents had died as well and whose bodies no one claimed. Some students fell into her arms as she stood at the school gate waiting for them. The sorrow of those students remains within her arms, unchanged since that day. I will not forget the 9th in my lifetime either. But if I continued to feel resentment, I would also feel the need to seek revenge.

I will go and observe how Americans live. So responding, I also told myself not to think of anything beyond that. While riding on the white road that stretched endlessly before me, however, the sensation that I was on land connected to the test site keenly weighed on my chest. I must go there, I decided without a second thought.

One day when the remainder of my stay in the U.S. was soon coming to an end, I asked Kei to take me to the Trinity Site. Huh? Tilting his head, he asked: What’s that? He had lived as a second-generation hibakusha. Yet, between him and myself, there had been no detailed discussions about the bombing or the a-bomb disease. When he was a college student, he once said, “No one likes to be condemned a prisoner without a term.” This was when he heard the news about Hiroshima-born second-generation hibakusha male siblings dying of leukemia in succession. I felt I had a debt to pay to Kei, and Kei was trying to distance himself from the 9th.

I returned to Japan without fulfilling my wish. Not that I had given it up. Trinity was the departure point of my August 9th. It was also the terminal point for me as a hibakusha: from Trinity to Trinity.

By traveling this circuit, I would absorb the August 9th hanging between those points in my life cycle. I would put an end to my ties to August 9th, which were impossible to sever, by swallowing them. This was my thought when I carried out my plan to visit Trinity. This was in the autumn of 1999.

I asked Tsukiko, who lives in Texas, to take me around. So I’m a substitute for Kana, commented Tsukiko as she accepted light-heartedly. Tsukiko and Kana, two years her junior, grew up together. During the war, Tsukiko had moved to Shimabara to escape the air raids,5 so she was not bombed. Around 1955 she went to Texas as a college student, and married a classmate who was a cowboy. She had four children with him, all boys. We had met through Kana. We were seeing each other after thirty years.

The convenient way to go to Trinity was to fly direct from Narita airport to Houston, Texas. I would then transfer to a flight for Albuquerque, New Mexico, and make that my base for moving around. Tsukiko and I arranged to meet at Houston airport. I flew to Houston, seated toward the tail end of a Continental aircraft. When I asked how I would recognize her, she answered, “look for a Japanese woman, no longer young.” We embraced each other without hesitation and headed toward Albuquerque. A district manager for a food company, Tsukiko’s waist was twice what it had been in her girlhood. She wore a ring with a single diamond.

New Mexico, where Trinity Site is located, is also where the American painter Georgia O’Keefe ended her life. She loved the mountains and wild lands of New Mexico and lived in Santa Fe, famous as a winter resort. She left this world at age 99. Which means a century. For one century, she lived as painter and woman, always active and engaged. Honoring her will, her ashes were scattered across New Mexico’s heights. We were riding in a car on that very earth. My purpose lay in Trinity, but I also secretly looked forward to becoming acquainted with the land where the life and death of Georgia O’Keefe became one. On September 30th, the day after our arrival at Albuquerque, we drove through the State of red soil to Santa Fe, Tsukiko behind the wheel. She had added this to our itinerary as a conversation piece for her husband, who was more interested in Santa Fe than Trinity.

After a ride of fifty minutes or so from the hotel, I spotted a sign for the Air Force base beyond the road for general traffic. The National Atomic Museum seemed to be located within this base. You had better take a look, said Tsukiko, as she tried to follow the car in front of us through the gate. From within a glass-sided guards’ office, a black soldier in military uniform waved his hand, ordering us to halt. He explained that personal identification or permission was required for a private car to enter the base. General public visitors to the museum were to leave their cars in the parking lot and transfer to special buses used inside the base. Tsukiko and I switched to a small bus driven by a red-haired man. A light-hearted driver, he whistled a tune while operating the vehicle. A twenty-minute ride through the base, crisscrossed by ordinary roads that made the area part military and part civil, brought us to the museum. It was a more modest building than I had imagined. Registering our names and nationalities, we went inside.

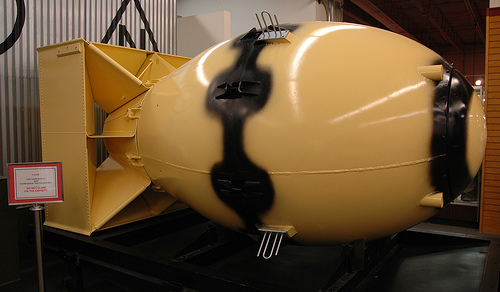

Men of a mature age were seated in chairs in a room near the entrance. It seemed that slides were being shown with the lights off. I looked in. The woman at the entrance of the room shook her head, pointing toward the far end of the hallway. She told me not to enter because a meeting was in session. I walked toward a large, free space connected to the hallway she pointed at. In the nearest corner was a sales place for gifts such as mushroom cloud T-shirts. As I walked past gift items, jewelry pins in a basket caught my eyes. Mixed among Stars and Stripes, double-headed eagles, and so forth, there were Fat Man pins. A gold hem surrounded the yellow body that was shaped like a round-bodied goldfish.6 The area where its ventral fan should be was painted black and inscribed FAT MAN in gold. The real Fat Man was a colossal bomb with a diameter of 1.52 meters, 3.25 meters in length, weighing 4.5 tons. The pin seemed to be designed as a one-hundredth scale model.

About 3 centimeters long, the small brooches conveyed a sense of Fat Man’s weight in their own way. I took one of them in my hand and gazed at it for a while. I wished to buy it as a souvenir. But then, its parent was the a-bomb that attacked Nagasaki.

As I wavered, a young white man, who was handing some change to a silver-haired woman, said to me, “The yellow goes well with your white sweater.” “Thank you,” I said and turned around to look across the shop.

Since entering the museum, I had felt as if someone were watching me.

In the shop, compartmentalized with wooden shelves and panels, were displayed small items like picture cards and U.S. Air Force banners. White sightseers were walking through the merchandise, but nobody was looking at me. Paying the young man for the pin, I moved to the next booth. At the center was a tattered Stars and Stripes in a glass display case, along with paneled photographs showing the history of the base and the Air Force as well as the history of the “ATOMIC BOMB” that united the three forces into one. On the wall leading to these panels, was a photograph of J. Robert Oppenheimer, father of the a-bomb and first director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory.

In 1953 Dr. Oppenheimer was purged from public service over security issues. The reasons were that he opposed the production of hydrogen bombs and, apparently, “knew too much.” The hydrogen bomb test at the Bikini atoll occurred the following year in 1954. If viewed in the Japanese way, he was what is known as a kokuzoku,7 a public enemy.

In the photograph on display, probably from when he occupied a seat of glory, he had a confident, intellectual gaze. A hero and enemy—as I walked on while thinking about this person who had traversed the bright and dark sides of life, my eyes caught the line, “Countdown to Nagasaki,” written on a large panel.

Oppenheimer with Gen. Leslie Groves

Oppenheimer with Gen. Leslie Groves

On the left, covering one-third of a white panel as large as an elementary school blackboard, was a photograph of the Japanese archipelago and its southern islands on the Pacific Ocean. On the wide space to its right, was an explanation in small print. While reading selectively, I noticed the vague backdrop to the text. The sepia landscape was of ruins. A white, winding path without pedestrians stretched upward from the lower right corner.

On the map of the Japanese archipelago and its southern islands was an acute-angled triangle drawn in red. I followed the three connected points with my eyes. One was Nagasaki, Kyūshū. At the end of a line that led south at a sharp angle from Nagasaki was Tinian in the Mariana Islands. Was the third point Okinawa? The red lines indicated the path taken by Bock’s Car, which flew out of Tinian at 3:49 a.m. (2:49 a.m. Japan time) on August 9, 1945, attacked Nagasaki, and returned to Okinawa.

Time stopped for me as I stood before the panel.

“Count down to Nagasaki.” When time toward death was beginning to tick, what were Kana and I doing at the armory at Ōhashi?

I stood before a trash bin, bitten by fleas as always, sorting waste paper collected from the entire factory. Kana was struggling with iron material at a work place that was seen to require the heaviest work. The words of the director—at the factory that had little paper for recycling—who said he heard a faint roar, prompted me to strain my ears toward the sky at the moment the bomb was released from the aircraft.

Eyes closed, I lowered my head, facing the photograph. The ruins in the background of the written explanation were of Nagasaki City, with Mount Inasa on the opposite shore.8 “Visible effects about equal to Hiroshima,” was the first report following the attack from Charles Sweeney, aircraft commander of Bock’s Car.9 Again, “The sight of the sudden destruction of most of one city hard to believe right away, even for an eye-witness”—this described the ruined city in the photograph.

What appeared in the photograph was, however, the surface of things. Behind the printed landscape were Instructor T, classmates A and O, and others who met instant death.

As I stood there unable to leave, someone moved in the corner of my eye. A man, with a belly that bulged so that the thread holding his shirt buttons seemed about to break, had just stood up from a chair. He was an elderly gentleman with a red, pointed nose tip.

Eyeing me, he withdrew into a little room meant as a rest area for staff and closed the door behind him. I looked toward the chair on which he had been seated. In front of several chairs was a TV set. Three white men sat, viewing a black and white documentary film. The old man seemed to have been adding his own explanation to the film’s narration. Perhaps the three found something unnatural about the way the elderly man stopped short and rose. They turned toward me. They may have guessed that I was Japanese. They shifted their eyes back to the screen, playing innocent. I looked at the screen from behind them. It was an Hiroshima-Nagasaki a-bomb documentary.

I had viewed a mushroom-cloud rising documentary of August 6 th and 9th several times. The film I was watching now, however, was being projected at the home site, in the cardiac region of the “United States.”10 The version I had seen may have been edited for overseas audiences. For better or worse, I felt like knowing the true mind of this country. The screen showed the final operation of transporting the huge canister known as Jumbo to the base of a steel tower,11 created in preparation for testing the plutonium bomb. Scientists seem to have felt less than confident about the a-bomb test: if the test were to fail, how would they handle it?

Plutonium is said to be a transuranic element, the most toxic on earth. It would be a disaster if a test failure caused the element to scatter all over the U.S. Jumbo was invented as a protective capsule. It was so large that a specially made trailer with 64 wheels was employed for transportation to Trinity.

The image on the screen changed to show the mushroom cloud that rose in the sky over Hiroshima. The backs of the three men seemed to tense up. “Oh,” I exclaimed, just loudly enough for them to hear. I wanted to put up an appearance of watching the cloud with the same curious surprise as theirs. But why should I have to go along with them? It was a mentality that I myself did not understand. On the other hand, I wished to let them know that a hibakusha was present.

The flashes that spread over Hiroshima collected under my eyes into a single, fat column. Next, an image of Hiroshima City without people was projected. One of the men looked at me with a searching eye.

Yes, it had been more than this, I commented in my mind.

I was thoroughly a hibakusha then. Until entering the museum, I had no consciousness of being Japanese or a hibakusha. Rather, what preoccupied me was my position in relation to Tsukiko, a long-time resident of the States. Starting when the elderly man left his seat, however, I became aware of being Japanese and a hibakusha, and the conduct of these Americans began weighing on my mind. The fact that the visitors were all white except Tsukiko and myself, too, seemed to make me feel as if I stood in opposition to them.

There were neither blacks nor Mexicans here. Not just here; all the visitors to Los Alamos and Trinity Site were white. Because my stay was short, I say this with no conviction. But, given that this was the core location of the bomb, the all-white scene appeared out of the ordinary.

The elderly man’s gaze destroyed my myth: I had implicitly believed that the abolition of nuclear weapons was common human sense. In listening to the explanations, perhaps the men felt intoxicated by the thought of a powerful mother country. The elderly man, who seemed older than I, must have fought in the 1940s. The history on display at the Atomic Museum represented the glory that his generation had won. I moved to a corner away from the men. In a glass case was a Japanese-language leaflet along with a photograph of the formally dressed Emperor. Because it was the flier I had heard of that hinted at the planned attacks of the 6th and 9th, I could not bring myself to read it. I passed by.

Had I picked up a copy prior to the attack and fled deep into the mountains . . . this thought crossed my mind momentarily. But I have lived my life the way I have. Even if I were now to be informed of a perfect opportunity for escape, there was nothing that could be done about it.

Tsukiko, who was walking ahead, returned and said, “Fat Man and Little Boy are on display in the corner over there.” I could see the two bombs on the wall at the front. Little Boy, which was dropped on Hiroshima, was slender, painted ultramarine. Fat Man, just like the jewelry pin, was yellowish white, or the color of egg yolk mixed with milk. This was a model of the bomb that had been dropped on Kana and me. I felt the fish-shaped belly of Fat Man with my hand. Beneath the smooth film of paint, I felt the roughness of the steel surface. “I wonder if the iron melted,” I said to Tsukiko. “I don’t know,” she answered bluntly, adding as she left the room, “I’ll be waiting outside, take your time.”

I retraced my steps to the center of the room and looked at the a-bomb models placed side by side. The two masses of iron stood hushed like coffins.

Fat Man display at the National Atomic Museum

I read in the Atlas of History of World Exploration that Spaniards began colonizing New Mexico in 1598.12 It lies as the destination of the Rocky Mountain Range that runs in the salt winds from the Pacific, from north to south, through Montana, Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado. I also learn that New Mexico became part of the United States following the Mexican war. It became a state in 1912, so it is among the most recent states on the mainland. This makes New Mexico younger than O’Keefe. Walking though its towns, one notices that there are many people of Mexican, Spanish, and Native American origins. The white population increases, I have heard, around the annual balloon festival held in Albuquerque.

Santa Fe is interesting in the history of conquests. Any land to which people direct their eyes seems to have an enticing charm before it has ever been trodden. Between 1528 and 1605, explorations were actively undertaken by Spanish parties pressing up from the south. To quote:

The first Spanish explorations, in the early 16th century, were more of an extended reconnaissance, frequently heroic, almost always arduous. They were fueled by a series of lingering geographical myths: the existence of a western sea-passage to the Orient; the search for the Seven Cities of Cibola. . . ; and the gold-rich land of Quivira described by an Indian to Coronado’s expedition, eager for tales of riches, in 1540.13

Santa Fe was among the areas that Coronado’s exploration party passed through en route to Quivira. Quivira has ceased being an illusory city, but, when checked against today’s map, the assumed location of this legendary place falls around central Kansas, further west than where many streams join the Missouri River in the area west of Topeka.

Enticed by the native American legend, exploration parties passed through Santa Fe as they made their way east and west in search of the city of treasure and gold. One party traveled from Santa Fe to the Gulf of California, another to St. Louis.

In the eighteenth century, the “urge to link New Mexico and California sparked the expedition of Friars Silvestre Escalante and Anastasio Domínguez, who became hopelessly lost on the desert mesas of Utah and trapped in the precipitous canyons of the Colorado.”14 The two friars departed from Santa Fe, hiked along the foot of the Rockies to enter Utah, then returned to Santa Fe after moving around the Colorado Plateau. The trail they took, drawn on an old map, makes a mushroom-shaped circle. The aim of the white explorers was as diverse as human desire, and explorations ended as an illusion. But nothing about Santa Fe was illusory for the Native Americans. For them, a golden city did not literally mean a city that possessed gold and silver; indeed, it was the sight of fine, red clay houses standing on red clay earth that represented the golden city.

Native Americans were naturally less than friendly toward explorers who disrupted their land at a time when tribal conflicts among them were also virulent. In order to divert their hostile eyes, explorers marched on through the wilderness with missionaries and friars at the fore. This reminded me of costumed ding-dong advertisement musicians marching through the streets in broad daylight. The wilderness scene that I imagined was somewhat comic, yet forlorn, and suggestive of bleak, boundless winds.

Most of the explorations were unsuccessful. They ended as bloody events, the explorers either becoming embroiled in tribal disputes or succumbing to their own internal rifts.

This earth, once abandoned as “a wilderness where no white culture can prosper” was, ironically, to be pioneered by aggressors’ greed and bloody battles.

Along that road, the rental car carrying me and Tsukiko headed for Santa Fe. In order to fend off the heat and sunlight, houses were thickly walled with the same red clay as that of the earth. This indeed was the golden city of Native American legend and desire.

After passing through the golden city, the landscape changed to that of a wasteland, scattered with the mesas that so troubled exploration parties.

“If you’re interested in sightseeing,” Tsukiko said while looking at a brochure, “one way would be to take freeway Route 40, which is part of Route 66, and enjoy the exquisite view of the streets covered with turquoise before entering Santa Fe.”

If the streets were so paved, maybe earth faults of turquoise the color of autumn sky ran across the mountains and on rock surfaces. Just imagining this was exciting, but the spread of the wild land seen from the car window was too good to give up: the brown, thorny prairie as rough as a scrubbing brush and the spacious mesas that looked like mountains sliced horizontally in a straight line by a well-honed falchion.15 I found a sense of restfulness in this space with no electric poles, television antennae, or buildings.

The road cut through the wilderness, which kept evolving in a large circular shape. Mesas in groups of three or four, which looked as if they had been placed deliberately as the earth’s stepping stones, slowly moved backward. Now and then, a group of low tablelands emerged right next to the road. Even those only as tall as a two-storied house were equipped with mesa-like countenances, with deep creases carved into their steep sides.

Across the walls of the mesas that added unevenness to the horizon, clouds of dust danced. Winds were racing through, for sure.

The monotonous plateau that I had seen below from the airplane a day earlier concealed this unexpected expression.

When the plane from Narita turned its head from the west coast of the continent toward Houston, I had a sense of something solid that bounced back from the earth’s surface. Looking out the window, I saw, through the white clouds flying past, a mountain range that looked moistened in steel color. “The Rockies,” said the TV screen that traced our course. With snow patches that remained, the mountains firmly grasped the earth like the roots of a large tree.

The aircraft began shaking, and when it was calm again, the landscape beneath my eyes changed to grassland. That wheat-colored prairie with no visible towns, villages, or gas stations was New Mexico. Amid the grass, water shone. A deep brown river, darker than the color of the grass, flowed in the form of a thrown rope. Beyond a curve of the river, I saw a foam-like white pool. I asked a young woman, seated next to me on her way home to her husband working at a Japanese company in Houston, if that might be Salt Lake. “I think Salt Lake is larger,” she said, leaning forward to take a look. There were two or three such white pools along the river. Utah, where Salt Lake is located, is a neighboring state though not directly adjacent; it was no miracle if there were salty lakes in New Mexico.

This riverine landscape, where water shone at the roots of grass and clouds of dust rose occasionally, had seemed totally flat when viewed from the air. After landing and driving in a car, I found that the world that till then had seemed a plain, was full of unexpected rises and falls.

In particular, the mesas that I saw for the first time seemed mysterious. These blocks of red clay—perhaps no man-made edifice outdoes them in size—were stately, large, and tall, and completely flat on top. Moreover, they did not have such petty-minded, gently spreading skirts, as would be expected of Japanese mountains.

If the Rockies and Himalayas rose due to diastrophism, what processes had the mesas undergone to appear on earth in square form?

Ordinarily I live on level ground, 5 or 6 meters above sea level. For me, nature that is higher than where I stand consists of mountains, or in other words, elevations from the earth’s surface. Mesas, I learn, are plateaus left behind after erosion. Passing winds brushed away the dirt, and the rain and light chiseled the earth’s surface, sculpturing plateaus in the course of hundreds of millions of years.

Sitting back in my seat, I gazed at O’Keefe’s world. Everything I saw from the car window could be found in her paintings.

I sense solitude and female corporality in the nature she depicted. As far as I know, only a few of her works directly portray human beings, but we see hints of the female body, both young and mature, amidst the natural objects like flowers and mountains that she fondly painted. In them may have been the ultimate form of the life she pursued.

Pink sand dunes smoothly connected like a girl’s breasts. Caverns reminiscent of a woman’s organs. The sandy land and the sky glowing in the setting sun suggest a woman in her early years of old age who has finished reproduction.

As nature reflects the body and the body mingles with nature, the body is given life in the form of mountains and flower nectar. O’Keefe committed her ashes into that repetitive cycle. A form of rebirth, perhaps?

As I was following my thoughts about this painter, a Native American reservation came into view. It was a settlement of twenty or thirty-one storied houses. Between those houses that stood in no particular pattern, was parked a small-size Japanese-made truck with a Romanized company name written on its body. Beyond it, at the far end of the path of trodden grass, was a casino with a small pennant fixed among the eaves. Another path branched off leading to a church. The cross atop the steeple with the sun behind it distanced itself as we drove by.

A black cross bearing a shadow—this had been O’Keefe’s favorite theme. She had made several paintings of a cross in the wilderness using the same composition: a wooden cross occupying the entire length of canvas, set against the space of New Mexico. The space differs from painting to painting in terms of the time depicted—night, dawn, and so forth—but the sun is invariably drawn at the back of the canvas. Invariably again, the crosses are all black. What thoughts did she put into depicting the cross in the shadow that stood between herself and the sun?

I closed my eyes. The sun in the wilderness reddened, pushing time forward by the minute.

We were heading for Los Alamos on a steep mountain road. One side of the road formed a cliff, and the mesas we had seen on the way to Santa Fe were visible far below. Winds blowing through the valley seemed to have brushed away the plants, for there was no green grass on the steep sides of the mesas. Stones and dirt had also been blown away, so that the sidewalls had holes resembling worm-eaten cabbage. From a distance, the round holes looked no larger than if they had been made with an adult fist. Holes of the same size were scattered on the surface of the sidewalls, and here and there grey rock showed partially. These holes were traces left by rocks that had been buried and then fallen off when winds swept away dirt. Rocks lay scattered at the base of the mesas. They were its dead members. I recalled my second trimester class that began after the war. Fifty-two students gone, our grade was one class fewer when the classes were reorganized.

When instruction for us survivors began, many desks in the classroom were missing their occupants. While taking roll, the teacher called the name of a girl who used to be seated before a now empty desk. “Absent,” someone responded. Each time this happened during roll call, I visualized the face and figure of the girl whose name had been called. It was painful to imagine the appearance of someone who was not where she should be. The space around each of those desks, white with dust, looked particularly expansive, conveying a sense of emptiness.

The mesas from which rocks had fallen were tranquil, having sucked away the sounds of the wind. “How many days would one survive here?” I said to Tsukiko behind the wheel. She replied to this abrupt question, “In that sunlight? No thank you, not for me.” “The surface of the cliff looks warm,” I continued. “If I lean against it with closed eyes, I may be able to go in perfect bliss.” Tsukiko laughed. “Running a family ranch, I know that any notion of the sun’s grace is naïve thinking,” she said.

After climbing all the way up, we looked down from the flat height at the city of Los Alamos below us. Tsukiko parked the red rental car at the center of a parking lot under the shining blue sky. This was the location that had been chosen as one of the three base areas for the Manhattan Project. The plutonium and enriched uranium produced at the two other locations, Hanford and Oak Ridge, were transported to Los Alamos, where atomic bombs were assembled. The Los Alamos National Laboratory built back then has been dismantled and rebuilt in a corner of the mountain across the road.

Tsukiko and I entered the Science Museum. After writing down our country and personal names, as we had at the Air Force Museum, the attendant who had waited the while explained to us the lay of the land where the Los Alamos National Laboratory was located, pointing at an aerial photograph. The building, a stylish one, stood on a lot situated atop a mountain of rock that spread its roots on the earth, and was the same color as the surface of the Rockies that I had seen from the airplane. The brave-looking mountain made me think of the day that would eventually come when the people of this country would fully conquer the Rockies. Between 1797 and 1812, the British explorer David Thompson first trod the Rocky Mountain Range, where only Native Americans had trafficked. It has not yet been two centuries since it was first discovered.

While listening to these explanations deep in thought, I learned that a documentary would be screened in about ten minutes. Entering the room behind several other people, we took seats in the rear. Spectators here were also, without exception, white. The film projected onto a large screen was an a-bomb history of the same kind as the film we had viewed on the TV screen at the Air Force Museum. I didn’t feel like seeing any more of it, and sat absent-mindedly while watching the ceiling of the dark room. I had had enough of atomic bombs and Bock’s Car. The characters who appeared in the film were all heroes: Dr. Oppenheimer, shaggy-haired Dr. Einstein, who was also on the labels of wine sold in the souvenir shop, and soldiers departing on an a-bomb carrier. They looked proud. While understanding this to be a record of victors, I found myself examining each detail with various objections and denials.

“The world needs not your tests.” In my tired mind, I reiterated these words I had read in a book.

At the Los Alamos National Laboratory, an accident occurred on August 21, 1945, days after World War Two was concluded. A young researcher by the name of Harry Daglian was at work, when “a plutonium source suddenly went critical and seared Mr. Daglian’s body” (Hibakusha in the U.S.A., by Haruna Mikio).16 The scientist died five or six weeks later.17

Tsukiko and I left the Science Museum. The sky over Los Alamos, just before noon, was clear and blue, and everything including the breeze and rustling of leaves seemed peaceful. But where would we go?

I’d love to see the river, I said. On the way to Santa Fe, we had crossed a bridge across the reddish brown river, the Rio Grande. On the railroad that stretched along the river, a rust-colored cargo train passed by. It was an old-fashioned train, reminiscent of the age of prairie wagons. The river was quite rapid there, tossing the tips of bush branches that hung in the water.

“We can go upstream,” said Tsukiko, who traced the river on a map with a fingertip.

It was that night. I learned about the Tōkai-mura accident.18 Unable to sleep, I wrote a long letter to Rui.

Dear Rui,

I am now at a hotel in Albuquerque, New Mexico, U.S.A. It is October 1, just past 10 p.m. Perhaps it’s the morning of the 2nd in Tokyo. One hour ago I returned to the hotel, casually turned on the TV, and learned about the critical accident at Tōkai-mura.

The scale of the accident greatly concerns me. I am writing you because I feel restless with too much time left on my hands before tomorrow morning, when I will head for Trinity.

When I told you about my plans to visit Trinity, you asked if I was an a-bomb maniac. The space in this world that the 52 people in my grade had occupied, the 52 spaces I cannot touch even if I extend my arms in a full embrace, what can I fill them with?

After leaving the Science Museum, I asked to stop the car on a pebble-scattered dirt road by the Rio Grande, and went down to the racing water. This being a country road, hardly any cars passed by. As I proceeded casually, Tsukiko told me not to walk into the grass. In Texas, she said, the first thing one checks for when rising in the morning and putting on shoes, when opening a desk or kitchen drawer, or when getting in the car, is the presence of scorpions and rattlesnakes. Dangers that cannot be imagined in Japan lurk here in familiar nature.

The dry riverbed where the car was parked lay between two streams, which seemed to join downstream. One was clear, and the other was reddish brown just like the main stream of the Rio Grande.

I sat down by the clear stream on the riverbed of stones that had turned white while being bleached under water. Five or six ducks swam in the upper course. They appeared to be wild ducks hatched and grown in nature. I saw eggs abandoned on the pebbles of the riverbed.

Will they hatch, warmed by the temperature of the pebbles and the heat of the sun? I have heard that ducks do not sit on their eggs. In terms of childraising, this would be like walking off the job. Here too are patients for you, Rui.

After locking the car and pulling on the door handle to make sure it was properly locked, Tsukiko sat by my side and then asked, “Why did you feel like seeing the river?” “The three of us often played together,” I answered, “stepping from stone to stone in the Nakajima River.” I was referring to a river that flows through Nagasaki City.

“That was long ago,” Tsukiko replied. But the Rio Grande is ten times fiercer than the Nakajima River in terms of both quantity and the flow of water. If possible, I wished to put my fingers in the main stream that formed streaks as it flowed near the bridge, and directly touch this river on the American Continent. The coolness of a stream, even a muddy one, is refreshing, isn’t it? Nature is never gentle, but holds no ill will. The sky lets torrents fall when it can no longer retain water drops, and rivers make their own paths as they like. Even as they swallow towns and force people to float, they have neither good nor ill will. A river that chisels the soil and divides the grass as it flows, with no concrete dykes or protective walls, its water permeating the desert and dirt—sublime, isn’t it?

In the human world, there are too many purposes and promises that have to be honored. I would like to have moments that are free of aim and reward, much like running water that has no purpose in and of itself. How liberated my heart would feel.

I asked Tsukiko, “Why was it that you left the museum?”

“The air conditioning in the museum was poor,” Tsukiko answered. “It was suffocating,” I agreed. She remained silent for a while then said abruptly, “I’m neither American nor Japanese. When I’m home with my husband and sons, I’m the only Japanese. But at that museum, I found myself to be half American. I can’t clearly locate myself, having lived longer in the States than in Japan. “Your citizenship?” “I gave up my Japanese citizenship the year my mother died,” Tsukiko replied.

A group of wild ducks swam this way, directing their shoehorn bills toward us. Apparently they knew they could get food from humans. I had thought they were part of untouched nature, but that was not the case. Feeling repugnance at their familiarity, I picked up a pebble and threw it into the water. Tsukiko then picked up an egg-sized stone and threw it with a swing of her arm. It made a big sound and sent up a spray. We had a hearty laugh.

The ducks playing in the Rio Grande River were tame to humans, but the water gushing out afresh every day continues to flow on the red earth at its own speed. It would seem that the river cleanses the mind by allowing one to spit out accumulated anxiety. I want to tell you, Rui, about an incident I encountered a week or so before leaving Japan. Since that day, I have been waking when the hour comes and listening, with my entire body, for a sound from the garden.

It was near dawn. I heard something hit hard against the glass door of the corridor. A pigeon had once hit it. This time the sound indicated greater weight and surface. From the back of my throat I uttered a sound that did not form words. Right away, I got out of bed and looked to the garden from the corridor. The rectangular back of a man was visible in the dark. He didn’t run, but walked away slowly without turning. I looked at the clock. It was 3:45. After checking to make sure that all the doors were locked, I woke Kei. Then the question arose as to whether I had really seen the man’s back in the dark, when the day had not quite yet dawned. I positioned myself at the same place in the corridor and looked out at the garden. One might call this inspecting the scene. Tree leaves and scattered pebbles showed in the purple air.

“I clearly saw his back,” I said, “and an untucked shirt.” “And below that?” Kei asked. “I didn’t see.” All that was imprinted on my eyes was a long, narrow, bony back.

In the morning, I walked around and checked the garden. I was petrified. For he had left something behind. While calling the police, I trembled. The surrounding space narrowed in all at once on me, and I experienced a sense of crisis as if we were about to be assaulted. The man’s aim had been to intrude. The item left behind made that clear.

We decided to install a sensor in the small garden, and to put on a crime prevention light and bolt the rain doors before going to sleep.

Rui, this incident made me realize my own loss of the sense of crisis. I had been embracing a groundless sense of freedom from care, thinking that our daily peace was protected.

I had kept glass doors slightly open to let the wind in on sultry summer nights, and sometimes I forgot to lock up. In the meanwhile, danger was always present. It’s up to me and my family to protect ourselves—I knew that through and through, and yet….

I didn’t want an innocent child to be touched by violence. When I repeatedly cautioned thus, Kei said, “If we take appropriate measures and there’s still a break in, then that’s that.” Yes, yes. But somehow it sounded wrong. Was it all right to be so complacent?

“Besides,” he added, “it’s not just the young people who might be assaulted. It could be you.” The thought had not entered even a corner of my mind, and I felt somewhat relieved.

Rui, how many years ago was it that you happened to be on a high-jacked airplane?

If one were to risk one’s life without considering the life or death of one’s adversary, there would be no need to go easy on him. One would attack him, or kill him. —What about when it’s between country and country, then? You would question this, Rui. You were always one to start by questioning daily life, then moving on to the larger questions facing countries and the world.

I put my pen down.

The sun rose late, and the morning of October 2 was still dark. I had to finish breakfast before my departure. When I was leaving Japan, an acquaintance who knows much about the States told me, “Hot spring buns won’t be sold either at Los Alamos or Trinity Site.20 Bring your own food and water,” because no food will be available there. I needed to fill my stomach with pancakes, green banana, and ruby-colored jelly provided at the hotel to prepare for whatever might happen in the desert. The dining room was open from 5 a.m. for guests going to the balloon fiesta. All ready for the trip, I went down with a knapsack on my shoulder. We planned to leave at 6:30.

The dining hall was full with balloon visitors. This is probably the only season that hotels in New Mexico become crowded, and this year Trinity Site was being opened on the same day as the annual Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta. The gate to Trinity Site opens twice a year, on the first Saturdays of April and October, allowing visits to Ground Zero.

When I returned from the Rio Grande River, the hotel parking lot was full of camp cars whose bodies were painted with pictures of colorful balloons. It seemed that contestants gathered from all over the world to compete for ingeniousness in balloon design. At a supermarket I bought a photo book titled Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta, which introduced the participating balloons. I learned that the Spanish word “fiesta” means a holy day for celebrating saints. The balloons had names: “Prism,” “Spider,” or the more dashing, “Go,” which was solid red against the blue sky. Americans who gathered in the dining room were more cheerful and relaxed than those I saw at the museums.

Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta

Albuquerque International Balloon Fiesta

A man whose aloha shirt revealed corn-color chest hair, a woman in shorts who was so opulent that her chest almost touched her belly—they greeted one another as they ate bagels and pancakes. There was also a woman who stood, drinking coffee in a stylish manner. They had hearty appetites, perhaps in implicit readiness to go out to the desert.

Plates of the buffet breakfast were quickly emptied. A young woman holding fruit and desserts on a silver tray walked around filling the plates. A woman with cherry-pink lipstick asked me with a wink, “Ready?” “Yes,” I answered cheerfully. The fiesta had already begun.

Loading the trunk of the car with drinks, Tsukiko and I too departed. Not a balloonist camper remained.

Trinity Site is on the outskirts of Alamagordo, about 190 kilometers southeast of Albuquerque. Our car entered the dusty wasteland as the rows of road lamps, dim in the morning mist, came to an end. The vista spread before us in a large circle, and distant mountain peaks to the east and to the left of the road began shining in gold. The morning sun was behind the mountains, the surfaces of which were still sunk in darkness. On the right side of the road, light spread from the mountain peaks to the grassy field at its base, minute by minute. As our car raced on, the mountain ridge to the east rose high and then fell low, with the sun sinking behind it and rising again. In response, the mountains to the west now became dark, then again, in the next moment, the grass on their surface shone like the golden hair of a little child.

Soon, as the dewy grassy fields rolled forth like river mist, the morning sun appeared in full from behind the mountains. 40 minutes had passed since leaving the hotel. We encountered no other cars. We met no other living creatures, not to mention people.

After 8 a.m. or so, we arrived at the freeway rest area, constructed of lumber. This was the first building we had seen after beginning our drive. It had a rectangular wooden frame with no windows or doors, and was only equipped with water and a washroom. The washroom was the only area that had walls or a door. A Native American stood guard. “I want to have a smoke, may I?” Tsukiko asked and drove into the concrete parking lot before the building. Several trucks and passenger cars were parked there. A man napped after a presumably long drive, with booted feet resting on the windowsill of his truck. Tsukiko parked next to him.

Tsukiko smoked as she crossed the wooden footbridge that led to the raised floor of the rest area. Reading the red letters on a standing signboard, she turned around and reported, “Watch out for rattle snakes, it says.” “Rattle snakes?” I asked, surprised.

“Yes, rattle snakes. ‘Walk only on the narrow concrete path and the wooden bridge. Dogs are not allowed to be unleashed into the prairie. You are responsible for any injuries incurred by snakes if you disregard this warning.’ OK?” Tsukiko confirmed, as I rounded my back in the cold morning air.

I crossed the wooden bridge after her, and stood facing the wild land to the west. The prairie stretched westward to the foot of the mountains. I inhaled deeply. Beneath the grass, snakes must be waiting for game to approach. Judging from the warning against stepping into the grass, they also lurked beneath our feet in the grass that I saw through crevices of the bridge.

What shape are they and what color eyes do they have, I wondered. Blue? Red? Rattlesnakes are killers, so, just like Fat Man and Little Boy, they probably have sleek body lines. I tentatively placed the form of the rattlesnake portrayed in Steinbeck’s “The Snake” in the prairie to the west.

A character observes the way the snake stalks its game, and says, “See! He keeps the striking curve ready,” and continues to explain: “Rattlesnakes are cautious, almost cowardly animals. Their mechanism is extremely delicate.” The main character of this short story, the “dusty grey” snake, is “nearly five feet long” and “comes from Texas.”

Rattlesnakes are perfectly suited to the wild land that was beginning to dry out in the morning sun. And it would not be strange if a 5-foot snake were to look up at Tsukiko or me. A 5-footer was not welcome. I kept to the wooden bridge and concrete path, and got in the car.

The sunlight had become painful to the eyes. Two hours and 40 minutes after departure, there was a slight change in the landscape. The wild scrub-brush land itself showed no sign of change, but I now saw plants the height of a boy growing here and there. People with detailed knowledge of the area would be able to read the geography from the look of the plants, but the Trinity Site is hidden and not on the map. What gave me a premonition that we had come close was a steel tower on a tableland ahead of us along with a huge parabola antenna.

“This must be it,” Tsukiko said as she slowed down. Five or six cars were parked fifty meters ahead of us. A female attendant, who was talking to one of the drivers, raised her hand to stop us. She approached and tapped on the window. Saying that Trinity Site was under the jurisdiction of the U.S. Army, she requested that we roll down the window. What lay ahead was more of the same wilderness. A fence made of logs and barbed wire was open, the gate to Trinity Site.

The attendant looked at us. “Two?” After verifying the number of visitors, she handed us two copies of a printed form. She told us to read and sign it. It was called “13 Entry Rules.” The gate opened at 8:30, closed at 2:00. Entering the Site, say at 2:00, if one stood at Ground Zero and circled the area within the fences once, it would be past 3:00. Evening dusk comes early in the wilderness, and it is dangerous. As if to warn of this danger, the standing signboard clarified the locus of responsibility: “End of State Maintenance,” meaning that this was the point where the property changed from state to federal land.21 From here on it was outside the jurisdiction of New Mexico, and the State was not responsible for any accident that might occur. Now I looked at the printed rules. Easy as it was to jump the fence itself, a series of verbal warnings enclosed the place ten- and twenty-fold. Among them were:

*Demonstration, picketing, sit-ins, protest marches, political speeches, and similar activities are prohibited.

*No weapons of any kind are allowed on White Sand Missile Range.

*You may not pick up or take Trinitite from Ground Zero. Trinitite is an artifact from a National Historic Landmark.

*Watch out for snakes. Rattlesnakes have been seen at Ground Zero and the ranch house.

*Pets should be kept in vehicles. If allowed out, all pets must be on a leash. If you leave your animal in your vehicle, be sure the windows are partially open to allow sufficient ventilation. The heat generated in a closed vehicle can kill a pet in very little time.21

After signing the document, we were allowed in. We drove along the long, narrow road sided by fences. Stopped again, we parked the car as guided by an attendant. Beyond that point was Trinity Site where no cars were allowed.

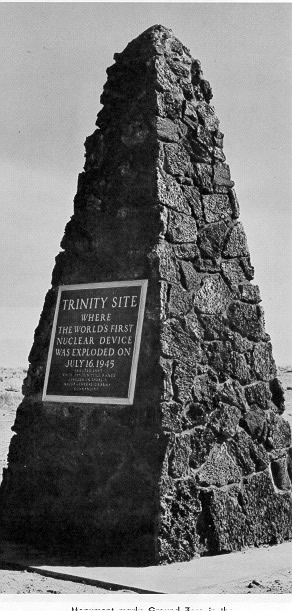

The “trinitite” mentioned in the rules referred to pieces of glass,22 but could also by extension mean everything in Trinity Site including pebbles, grass, flowers, dirt, and sand. Trinity Site refers to the small wilderness surrounded by fences approximately 3 meters high within the wilderness. Its approximate center is Ground Zero, the epicenter of the plutonium explosion test. At Ground Zero stands a National Historical Monument, an obelisk built with stones, perhaps also about 3 meters tall. In short, everything within Trinity Site, down to the dirt that sticks to a visitor’s shoes, is top national secret and open to the public.

National Historical Monument at White Sands Missile Range

National Historical Monument at White Sands Missile Range

Inside the fences was a grassy area 6 or 7 baseball fields in size. This area, including the space outside the enclosure, was probably used as the missile testing range. I hadn’t thought that the White Sands in tourist photos and White Sands the missile range were one and the same place, but I learned that “42,000 missiles had been fired here.” The warning sign told us, as a matter of commonsense, to be careful because fired materials could be buried in some places.23 A booklet titled Trinity Site 1945-1995 amply explained the danger level: “Radiation levels in the fenced, ground zero area are low…. A one-hour visit to the inner fenced area will result in a whole body exposure of one-half to one millirem. . . a U.S. adult receives an average exposure of 90 millirems every year. . . the Department of Energy says we receive between 35 and 50 millirems every year from the sun and from 20 to 35 millirems every year from our food. . . . The decision is yours.”24

If one stays within the fenced area for one hour, 0.5 to 1 millirem of radiation will be added to the body. The yearly exposure for an American adult being 90 millirems, the amount at Trinity Site cannot be considered low.

Getting out of the car, we walked toward the fenced area carrying mineral water bottles, which were permitted. Approximately 200 visitors were there. Many were families, and fathers holding children’s hands caught my eyes. Perhaps mindful of the thorny desert plants and short, possibly radioactive grass under their feet, visitors walked silently, looking down. The only things that moved were humans walking through Trinity Site. It is unlikely that birds nest in a desert devoid of trees.

I listened for sounds in the hushed wilderness. I wished to hear the sounds of the small but powerful grass seeds that split open in the warm sun. Even the scratchy noise an insect makes on sand while sliding down a doodlebug pit would have been fine. I wanted to hear the sounds of a living creature.

I walked toward Ground Zero, stopping when I reached just outside the circle of visitors surrounding the stone monument. I lifted my face upward and looked around. It was a boundless expanse of bleak land where nobody could hide. Nothing was taller than the earth’s surface except for humans, the fences surrounding Trinity Site, the distant red mountains connected to the horizon, and the Ground Zero monument that stood before me.

In July over fifty years ago, an atomic flash had streaked from this point in all four directions. I have heard that on the test day, there had been a torrential rain from early in the morning, which is rare in New Mexico. The test was carried out despite the storm.25 The flash singed the rain to white foam, ran across the wilderness, burnt the sides of the unarmed mountains, and danced up to the sky. A hush followed. Living creatures on the wild land were silenced before they could even assume an attack posture.

From the bottom of the earth, from the distant mountain range exposing its red surface, and from the brown wilderness, soundless waves pressed toward me. I squeezed myself. How hot it must have been.

Until I stood on Trinity Site, I had thought that the first victims of nuclear damage on earth were us humans. I was wrong. There were elderly victims here. They were here, without being able to weep or cry out.

Tears came to my eyes.

Since beginning the walk along the fenced-in corridor as guided by the attendant, the awareness of myself as a victim, which I had felt so strongly, had disappeared from my mind. It seems that in walking toward Ground Zero, I had reverted to being fourteen years old, before I was bombed. It may be that, as I started walking toward the unknown place called Ground Zero, I had returned to “a time” before experiencing August 9th. When I stood before the Monument, I experienced the true bombing.

As I look back, I shed not a single tear on August 9th. While running away and mingling with groups of people who had lost their shape—hands, legs, and faces–I did not shed a tear. A line formed like that of midsummer ants on the scorched field of Urakami. It was composed of people who could still walk and sought treatment. Facing the line, one doctor gave treatments. He was seated on a cracked stone, a bandage around his head. The city of Nagasaki, which had turned to rubble, was in clear view all the way to the sea, and here too, humans were the only things taller than the earth’s surface. Eyeing the landscape that loomed in the sunlight, I fled with all my might.

Three days later, my mother walked 28 kilometers from the place to which the family had fled to find me. On the way, she mentioned my work site to students headed for rescue work to Urakami and asked, “if you find thin bones they belong to my daughter, so please bring them back.”

When she found me safe, she embraced me to her chest and cried, saying, “You are alive.” Even then, I did not shed tears. It may be that, for the first time as a human being, I now shed the tears that I did not shed on August 9th. Standing on the silent earth, I trembled at the earth’s pain. To this day, the days of my life had been of merciless pain that stung my body and mind. Yet that may have been an epidermal pain that was derived from the 9th. I had temporarily forgotten that I was an hibakusha, but, on this silent earth, I was in fact seeing the landscape of my escape, which I had suppressed in a corner of my heart over the years—seeing myself on that critical day.

The back of an old man walking toward Ground Zero caught my eye. He was walking alone, away from the groups of people. Around 72 or 73 years of age and with a long strongly built torso, he could be a disabled former serviceman. Perhaps he had weak eyesight, for he wore dark glasses. Nobody accompanied him. I imagined that he joined a bus tour to visit Ground Zero while he could still walk. I was drawn to his form that conveyed sadness. What was the first half of his life like? Judging from the fact that he took the trouble to visit Trinity Site, he probably fought in World War Two like the old man at the museum or Tsukiko’s husband.

The elderly man, who was feeling Trinity Site with his stick as he walked, stopped outside the crowd surrounding the stone monument. With one hand placed over the other on top of the stick, he viewed the monument from a distance.

Three or four boys in camouflage clothes ran past him. Another played alone, throwing a red Frisbee to the sky.

Fat Man, housed at the Atomic Museum in the Air Force base until yesterday, was on display within the fence, having been transported there overnight. It was the sibling of the plutonium bomb used in the test explosion. Twice a year, it returns home.

Tsukiko and I were walking hand in hand before we realized it. A few five-petaled flowers, closely resembling a kind of quince seen in hills and fields in Japan, were abloom amidst the grass. There were also glossy, yellow flowers. We crouched to gaze at those flowers that kept themselves flat to the ground. “I wonder if Kana is alive,” Tsukiko said softly. “Yes, trust me,” I replied.

After taking a look at what was left of the crater after the test explosion,26 we walked toward the exit, which had also served as our entrance. There was a crowd. I had not noticed it before, but things like radium dials from old watches and clocks were placed on a table.27 A female safety personnel officer applied a Geiger counter to a radium dial. The pointer swung and the counter began to buzz.

Some of these items might date as far back as that morning after the rainstorm. “These are still radioactive,” the attendant explained pointing at the counter’s pointer. The sound became loud, then weak, undulating. “Oh,” Americans shook their heads, moved by the power that remained from decades ago. “That’s something,” Tsukiko and I too shook our heads.

The attendant looked as much as to say, “I hope you’re impressed.” As I gazed intently, moved, I started to feel comical about myself and the people surrounding the table. I felt like applying the Geiger to my body for them to see. If the counter started to make harsh sounds, everyone would be shocked, I thought.

Although it partly depends upon the material, the life of radioactivity sent out on earth is said to be semi-permanent. According to an acquaintance living in France, a counter began to make noise once in Madam Curie’s laboratory.

By the side of those rusty instruments was a glass case containing a stone. It was a perfectly round pebble with a diameter of about 1 centimeter. It looked grey as a whole, but on taking a good look I saw that it was made of white, brown, green, and red grains of sand mixed together. Pointing at the lusterless stone, the attendant began to explain.

“This round stone comes from sand and dirt blown up by the atomic bomb test explosion. They danced around, came together in the air, melted at a high temperature, and turned into this solid spherical shape. We call these stones ‘pearls’.” It was admirably spherical.

A member of the Bock’s Car crew that attacked Nagasaki writes: “On earth, something was happening in excess of the test performed in the desert of Alamogordo in New Mexico.” I wonder if humans who melted at high temperature turned into sphere-shaped pebbles and danced in the air. Young people’s bones, I hear, are shiny pink. I wished, at the very least, that the bones of the friends I had lost were lovely, pink pearls. In front of the table displaying the “pearl,” local reporters were preparing for an interview. Surrounded by people, stood two Japanese men. They were hibakusha from Hiroshima, about to be interviewed. Wearing T-shirts, the two stood looking tense amidst American onlookers.

They stood upright, with uplifted faces.

That night, I wrote to Rui once again. I attached a poem to the letter:

One second after the explosion of the plutonium bomb

what I saw was

a ball of fire 1,000,000 degrees Centigrade at the core 7,000 degrees on the surface

with a radius of 340 meters

a blast at a speed of 250 meters per second

shooting radioactivity and heat rays of 300,000 degrees

making the sun 6,000 degrees on the surface

lose its dazzling brightness

and fall red and large.That light and cloud rivers of corpses

the death cries of fathers mothers and children

the howling of the flaming sea running at full speed

the night groaned on the devastated fields

each of the several tens of thousands who breathed their last—

Xavier and the Apostles

who stand atop the Urakami Church

you know all these.

Fathers mothers siblings friends

the place you live now

is Paradiso,28 a distant land brimming with water and light.

We survivors too will eventually depart

but fat alley cats walk slowly

people move their big bellies swaying

our destination

ah, where will it be?By now a few hydrogen bombs, it is said, are enough to make

rising clouds and smoke stream all the way to the ends of the earth

a nuclear winter will then cover the globe

and all living things will become extinct.

Beyond Hiroshima and Nagasaki history

at length has come to this.

Xavier and the Apostles

standing upon the remains of the Urakami Church

some day if the world ends at that moment

what will you see?

—In the fortieth summer—Itō Yasuko29

At the time of the bombing, the poet was a second-year student at N Higher Girls’ School. Her older sister was one grade above me (she died at age 42).

—The world needs not your tests—

What are your thoughts, Rui?30

Notes

1 Students, 7th graders and up, were mobilized as workers during World War Two. At first it was only occasional, but was extended to a period of four months in 1943, then all year in 1944 and 1945.

2 Bock’s Car, the plane that dropped the a-bomb on Nagasaki was named after Frederick Bock, the plane’s original commander (replaced by Charles Sweeney for the flight to Nagasaki); also sometimes spelled “Bocks Car” or “Bockscar.”

3 This refers to the recital celebrating Kana receiving a new professional name when she became an accredited master singer of Edo-style songs sung while plucking the shamisen. The event is mentioned in the title story in the same volume, “Human Experiences over a Long Time” (Nagai jikan o kaketa ningen no keiken). It is customary for such a performer to prepare a square furoshiki wrap or an oblong hand cloth, dyed with their new name or a design associated with it, for each member of the audience to take home.

4 Prior to 1945, girls’ higher schools provided 4 or 5 years of secondary education. High schools of 3 years that followed 5 years of middle school, were only for boys.

5 The Shimabara peninsula in western Kyūshū is across the Tachibana (Chijiwa) bay from the Nagasaki peninsula. It is famous for the Shimabara Uprising (1637-38), in which early Christians fought against the Tokugawa Shogunate that banned Christianity.

6 The reference is to ranchū, a variety of fancy goldfish, egg-shaped, fan-tailed, and without a dorsal fin, developed in Japan by cross breeding different specimens of lionhead goldfish, their Chinese precursor.

7 Literally, “traitor to the country.” The expression was often used during the war.

8 The Urakami River runs through Nagasaki City and pours into Nagasaki inlet. The city center lies to the east of the water, Mount Inasa to the west.

9 From the message Commander Frederick Ashworth ordered radio operator Sergeant Abe Spitzer to transmit to Tinian soon after leaving Nagasaki. Lane R. Earns, “Reflections from Above: An American Pilot’s Perspective on the Mission Which Dropped the Atomic Bomb on Nagasaki.”

10 In terms of the a-bomb, New Mexico was the heartbeat of the “United States,” which the author spells in katakana syllabary instead of, as elsewhere, referring to the U.S. as America (amerika in katakana).

11 The steel-made, 240-ton Jumbo was designed to contain the explosion from the 5 tons of conventional explosives used to compress the plutonium in case the chain reaction failed, so that the precious plutonium could be recovered. In the end it was decided that Jumbo was unnecessary. It did serve, however, as one measure for calculating the effect of the explosion. It survived, although not the steel tower on which it was placed. Two years later it was buried in the desert near Trinity after a failed attempt to destroy it. Recovered in the 1970s, it is still displayed near the entrance of the Trinity Site fence. See George Walker, Trinity Atomic Website (1995-2003).

12 Felipe Fernández-Armesto (ed.). The Times Atlas of History of World Exploration: 3,000 Years of Exploring, Explorers, and Mapmaking (NY: Harper Collins Publishers, 1991), 90.

13 Ibid., p. 91.

14 Ibid., p. 93.

15 The reference here is to a kitchen scrubbing brush without a handle, brown and oval-shaped.

16 Haruna Mikio, Hibakusha in the U.S.A. Tokyo: Iwanami, 1985.

17 Harry Daglian died on September 15, 1945.

18 A critical accident that occurred on September 30, 1999 at the JCO Co. Ltd. Conversion Test Building at Tōkai-mura, about 75 miles northeast of Tokyo, when workers were converting enriched uranium into oxide powder for use in preparing fuel for the experimental Jōyō fast breeder reactor. The chain reaction, which gave off intense heat and radiation, could not be stopped for 18 hours. At least 49 people were contaminated with radiation, including 39 JCO staff, seven residents, and three firefighters who transported the injured workers. Two of the workers died.

19 Steamed buns with sweet bean fillings are sold at Japanese hot spring resorts, enjoyed there or brought home as local gifts.

20 Quoted from information supplied by the Public Affairs Office, White Sands Missile Range, NM, June 30, 2007.

21 Quoted from the current “White Sands Missile Range Top 10 Entry Rules,” Public Affairs Office, White Sands Missile Range, NM, June 29, 2007.

22 The blast left a large crater coated by radioactive glass of light green color, later called trinitite. The crater was filled in soon afterwards, and the remaining trinitite was mostly removed when the site was bulldozed in 1952. But visitors can still find plenty of pieces in the dirt. “New Theory on the Formation of Trinitite” under Trinity Site on the White Sands Range’s official website.

23 There are large signs at all missile range entrances, warning that White Sands Missile Range is a military test range where weapons have been tested for many years and that unexploded munitions may exist. The exact wording on a large red and white sign, with the English on top and Spanish on the bottom reads: “WARNING Entering active test range. Areas potentially contaminated with explosive devices. Stay on the roads. Do not disturb any items. If items are found call police at 678-1134.” (Public Affairs Office, White Sands Missile Range, June 30, 2007.)

24 “Radiation at Ground Zero” in White Sands Missile Range’s official site, where instead of the Department of Energy, it cites the American Nuclear Society.

25 The test was initially planned for 4:00 a.m. It was postponed to 5:30 due to thunderstorms that began at 2:00. It was feared that the danger from radiation and fallout would be greatly increased in the rain, and that the lightning and thunder might accidentally set off the test bomb. Shortly after 3:00 the weather improved, and after the meteorologist’s weather report at 4:40 a.m., at 5:09:45 the twenty-minute countdown began. Richard Rhodes, The Making of the Atomic Bomb (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1988), 666-67; Peter Wyden, Day One Before Hiroshima and After (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1984), 210-11.

26 See footnote 19.

27 The display manned by safety personnel has pieces of Trinitite from the test explosion and “items that show radiation in other settings from later years—radium dials on old watches and clocks, the glaze in red Fiesta wear from decades ago, etc.” Monte Marlin, White Sands Missile Range, June 29, 2007.

28 “Haraiso” in the original, from the Portuguese “Paradiso,” as written by early Japanese Catholics.

29 The poet was one year junior to the author at the girls’ school. She sent this poem in a letter to the author.

30 In his commentary included in volume 6 of the Collected Works (Hayashi Kyōko zenshū, 2005), the critic Kuroko Kazuo quotes an earlier version of the ending, which refers to the deaths of two victims of the Tōkai-mura nuclear accident (see 18 above) instead of the death of a Nagasaki survivor. He suggests that, by the name Rui, “it is natural to consider that the author deliberately implies humanity.” Written phonetically in katakana throughout the story, the name shares the same sounds with the kanji rui in jinrui (humanity). Kuroko’s point is consonant with the characterization of Rui as “one to always start by questioning daily life then moving on to the larger questions facing countries and the world” (p. 156). “What are your thoughts?” This final line is at once the narrator’s question to her friend and one the author poses to humanity.

This translation benefited from the editing assistance of Yumi Selden and Miya Elise Mizuta.

About the author

Hayashi Kyōko was born in Nagasaki in 1930. She spent much of her prewar and wartime childhood in Shanghai. Returning to Nagasaki in March 1945, five months before the war ended, she attended Nagasaki Girls High School. Hayashi was working at a munitions plant in Nagasaki at the time of the atomic bombing on August 9. She was seriously ill for two months, and like the majority of bomb survivors, suffered thereafter from fragile health and remained in fear of [or just: fragile health and fear of] the symptoms that affected offspring of survivors.

Hayashi made her literary debut with the Akutagawa Prize-winning “Ritual of Death” (Matsuri no ba, 1975, trans. Kyoko Selden, 1984), which records her exodus from the area of devastation and eventual reunion with her family. Hayashi continued to write of the atomic bomb in a novella “Masks of Whatchamacallit” (Nanjamonja no men, 1976, tr. Kyoko Selden, Review of Japanese Culture and Society, 2004) and a sequence of twelve short stories called Cut Glass, Blown Glass (Giyaman bîdoro, 1978). “Yellow Sand” (Kōsa, trans. Kyoko Selden, 1982) has a special place as the fifth story in the sequence and deals with the author’s experience in Shanghai. The other eleven stories concern the bombing, with the only reference to Hayashi’s Chinese experience found in a flashback in “Echo” (Hibiki). Hayashi gives a fuller account of her Shanghai experience in The Michelle Lipstick (Missheru no kuchibeni, 1980), while in Shanghai (1985 winner of the Women’s Literature Prize), a travelogue, she revisits the city thirty-six years after she had last seen it.