The Battle of Singapore, the Massacre of Chinese and Understanding of the Issue in Postwar Japan

Hayashi Hirofumi

Shortly after British forces surrendered in Singapore on 15 February 1942, the Japanese military began operation Kakyou Shukusei [a] or Dai Kenshou [b], known in the Chinese community of Singapore as the Sook Ching (“Purge”) [c], in which many local Chinese were massacred.[1] Although the killings have been investigated extensively by scholars in Malaysia and Singapore, this article draws on Japanese sources to examine the events.

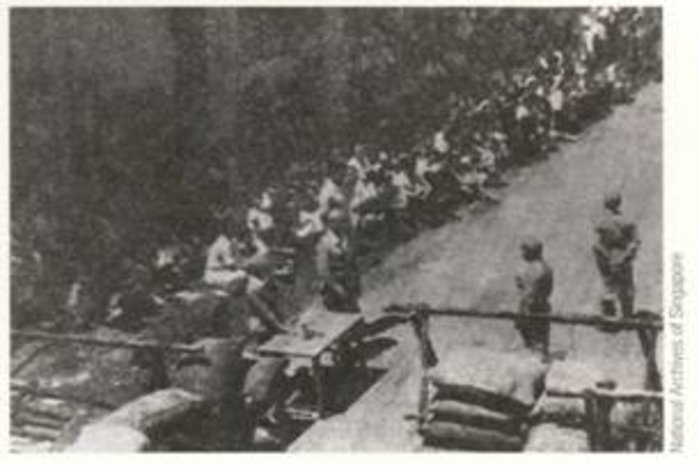

Chinese inspected by Kempeitai following the capture of Singapore

The first point to be considered is why the massacre took place, and the second is how the massacre has been presented in postwar Japan. Although even ex-Kempeitai officers involved have admitted that the killings were inhumane and unlawful, little attention has been paid to the episode in Japan. While there has been valuable research carried out on the Japanese military administration of Malaya and Singapore, no detailed Japanese study of the killing has appeared. Moreover, while the Singapore Massacre is well known to scholars, similar killings in the Malay Peninsula only came to the attention of the Japanese public in the late 1980s after I discovered documents relating to the Japanese military units involved.

Why did the Japanese Military Massacre Chinese in Singapore?

On the night of 17 February 1942, Maj. Gen. Kawamura Saburo, an infantry brigade commander, was placed in charge of Japan’s Singapore Garrison. The next morning, he appeared at Army Headquarters and was ordered by 25th Army commander, Lt. Gen. Yamashita Tomoyuki, to carry out mopping-up operations. He received further detailed instructions from the chief of staff, Lt. Gen. Suzuki Sosaku, and Lt. Colonel Tsuji Masanobu. Kawamura then consulted with the Kempeitai commander, Lt. Col. Oishi Masayuki. The plan to purge the Chinese population was drawn up in the course of these meetings. Under this scheme, Chinese males between the ages of 18 and 50 were ordered to report to mass screening centers. Those deemed anti-Japanese were detained, loaded onto lorries, and taken away to the coast or to other isolated places where they were machine-gunned and bayoneted to death.[2] My survey of official documents of the Japanese military revealed two sources that specified the number massacred. One is Kawamura’s diary that shows the figure as 5,000.[3] The other is an issue of the Intelligence Record of the 25th Army (No.62, dated 28 May 1942) prepared by the staff section of the 25th Army.[4] This secret record states that the number missing as a result of bombing and the purge was 11,110. This second record is important because it was drawn up as a secret document shortly after the purge took place. However, it includes both bombing and purge casualties and offers no basis for the figure.

In Singapore it is generally believed that the number killed in this event was about 50,000.[5] However, on the basis of materials available in Japan, Singapore, and the UK, I find no basis for this figure. Although I can not present exact figures, my estimation is that a minimum of 5000 died; I can offer no figure for the maximum. The issue of numbers remains unsettled.

The mass screening was carried out mainly by Kempeitai personnel between 21 and 23 February in urban areas, and by the Imperial Guard Division at the end of February in suburban districts. Most accounts of the killings include a map that shows the island divided into four sections, and explain that the Imperial Guards, the 5th Division, and the 18th Division carried out the mass screening in suburban districts.[6] However, on 21 February, the 25th Army ordered both the 5th and 18th Divisions to move into the Malay Peninsula to carry out mopping-up operations.[7] The order assigned the Imperial Guard Division to conduct a mass screening of non-urban areas of Singapore, with the 5th and the 18th Divisions responsible for the rest of the Malay Peninsula. According to war diaries and documents relating to these two divisions, neither played a role in the mass screening in Singapore. The 1947 British war crimes trial in Singapore[8] prosecuted the commander of the Imperial Guard Division, Lt. Gen. Nishimura Takuma, on charges related to the Singapore Massacre, but not the commanders of the 5th or 18th Divisions. This version of events is correct, and the conventional mapping of the massacre is incorrect.

Kempeitai headquarters: the old YMCA Building

It is important to note that the purge was planned before Japanese troops landed in Singapore. The military government section of the 25th Army had already drawn up a plan entitled, “Implementation Guidline for Manipulating Overseas Chinese” on or around 28 December 1941.[9] This guideline stated that anyone who failed to obey or cooperate with the occupation authorities should be eliminated. It is clear that the headquarters of the 25th Army had decided on a harsh policy toward the Chinese population of Singapore and Malaya from the beginning of the war. According to Onishi Satoru,[10] the Kempeitai officer in charge of the Jalan Besar screening centre, Kempeitai commander Oishi Masayuki was instructed by the chief of staff, Suzuki Sosaku, at Keluang, Johor, to prepare for a purge following the capture of Singapore. Although the exact date of this instruction is not known, the Army headquarters was stationed in Keluang from 28 January to 4 February 1942.

Rebuttal of the Defense

Let us consider the justification or defense for the actions of the Japanese army presented by some Japanese writers and researchers. One of the major points is that the Chinese volunteer forces, such as the Dalforce, the Singapore Overseas Chinese Anti-Japanese Volunteer Army, fought fiercely and caused heavy Japanese casualties. This is supposed to have inflamed Japanese anger and led to reprisals against local Chinese.[11] About 600 personnel from among the 1,250-strong Dalforce volunteers were sent to the front. Some 30 per cent of Dalforce personnel either died in action or were killed during the subsequent Purge.[12] It is generally said in Singapore that the Dalforce personnel fought fiercely.[13] Whatever their bravery, however, their role seems exaggerated in Singapore accounts. The volunteers of Dalforce were equipped only with outdated weapons. Japanese military histories make no reference to Chinese volunteers during the battle of Singapore, and report that the opposition put up by British forces was weaker than expected. The greatest threat to the Japanese was artillery bombardment.[14]

During the war crimes trial of 1947, no Japanese claimed that losses suffered by Japanese forces at the hand of Chinese volunteers contributed to the massacre. As noted above, the 25th Army had planned the mass purge even before the battle of Singapore. This sequence of events clearly rebuts the claims.

A second point raised is that the Chinese in Malaya were passing intelligence to the British and that Chinese guerrillas were engaged in subversive activities against Japanese forces during the Malayan campaign, for example by flashing signals to British airplanes. The Kempeitai of the 25th Army was on the alert for such activities during the Malayan campaign, but made only two arrests. Kempeitai officer Onishi Satoru said in his memoirs that they had been unable to find any evidence of the use of flash signals and that it was technologically impossible. Thus, this line of argument is refuted by a military officer who was directly involved in the events.[15]

A third explanation offered for the massacre is that anti-Japanese Chinese were preparing for an armed insurrection, and that law and order was deteriorating in Singapore. They claim that a purge was necessary to restore public order, and this point was raised at the war crimes trial in Singapore.[16] One piece of evidence cited by the defense during the trial was an entry in Kawamura’s personal diary for 19 February that purportedly said looting still continued in the city. The same evidence was presented to the Tokyo War Crimes Trial. However, the diary actually says that order in the city was improving.[17] The extract used during the trials was prepared by a Japanese army task force set up to counter charges made during war crimes trials by the Allied forces. Clearly the evidence was manipulated.

Otani Keijiro, a Kempeitai lieutenant colonel in charge of public security in Singapore from the beginning of March 1942, also rejected this line of defense, severely criticizing Japanese atrocities in Singapore.[18] Onishi stated that he had not expected hostile Chinese to begin an anti-Japanese campaign, at least not in the short term, since public security in Singapore was improving.[19]

The fourth argument is that staff officer Tsuji Masanobu was the mastermind behind the massacre, and that he personally planned and carried it out. Although Tsuji was a key figure in these events, I believe that researchers have overestimated his role. At the time of the war crimes trials, Tsuji had not been arrested. As soon as the war ended, he escaped from Thailand to China, where he came under the protection of the Kuomintang government, having cooperated with them in fighting the communists. He later secretly returned to Japan in May 1948 where he was protected by the US military, namely G2 of GHQ.[20] In this situation, the defense counsel of the war crimes trial of 1947 attempted to pin all responsibility on Tsuji, who could not be prosecuted. This point will be discussed in more detail below.

Let us now examine the reasons why the Japanese in Singapore committed such atrocities. I limit the discussion to internal factors of Japanese military and society.

First, it should be noted that the Japanese occupation of Singapore began a decade after the start of Japan’s war of aggression against China. After the Manchurian Incident in 1931, Japan invaded and occupied Manchuria, setting up the puppet state of “Manchukuo” in 1932. The Japanese army faced a strong anti-Japanese campaign and public order remained unstable. The military responded by conducting frequent punitive operations against anti-Japanese guerrillas and their supporters. Under normal circumstances, those arrested in these operations should have been apprehended and brought to trial for punishment. However, Japan forced Manchukuo to enact a law in September 1932 that granted authority to army officers, both Japanese and Manchurian, as well as police officers, to execute anti-Japanese activists on the spot without trial. This method of execution, which denied judicial due process to Chinese captives, was usually called Genju Shobun (Harsh Disposal) or Genchi Shobun (Disposal on the Spot) by the Japanese military.[21] With this law in place, the Japanese military and military police killed suspects without trial or investigation. Those killed were not only guerrillas but also civilians, including children, women, and the aged. Such inhumane methods were legalized in Manchuria. From 1937, Genju Shobun was applied regularly throughout the China-Japan War., with civilians denied the right of trial and Chinese soldiers denied prisoner of war status[22]

Yamashita Tomoyuki, the 25th Army commander who directed the invasion of Malaya, played an important role in the evolution of Genju Shobun. As chief of staff of the North China Area Army in 1938-1939, he formulated an operational plan for mopping-up in northern China that drew on the Genju Shobun experience, having earlier been stationed in Manchuria as Supreme Adviser to the Military Government Section of Manchukuo.[23] At the time, the Chinese communists had a number of base areas in northern China. In 1940, following Yamashita’s transfer, intensive cleanup operations called San guang zhengce (Kill All, Loot All, Burn All; J. Sanko seisaku) were launched involving unbridled terror during which numerous people in contested areas were massacred or driven from their villages. Yamashita was the link that connected Japanese atrocities in Manchuria and North China with those in Singapore. [24]

During the final phase of the war, Yamashita was appointed commander of the 14th Area Army in the Philippines, where he surrendered to US forces at the end of the war. While he had experienced trouble with anti-Japanese guerillas in the Philippines, he commented to the deputy chief of staff that his policy of dealing harshly with the local population in Singapore had made the local population there become docile.[25]

The army order that began the purge in Singapore and Malaya was issued to the Singapore Garrison Commander, Kawamura by Army Commander Yamashita. When Kawamura presented Yamashita a report on the operations of 23 February, Yamashita expressed his appreciation for Kawamura’s efforts and instructed him to continue the purge as necessary.[26] Yamashita was not a puppet of Tsuji but an active instigator of the Singapore Massacre.

A third important point is that the headquarters of the 25th Army included other hardliners aside from Tsuji and Yamashita. A notable example was the deputy chief of the military government of Singapore and Malaya, Col. Watanabe Wataru.[27] He was the mastermind behind the forcible donation of $50 million and the “Implementation Guidance for Manipulating Overseas Chinese”, which set out the fatal consequences of non-compliance. His earlier career included time spent as chief of a secret military agency in both Beijing and Harbin. He delivered a speech at the Army Academy in 1941 advocating strong pressure against those who “bent their knees” to the British and thereby betrayed East Asia. The lesson he derived from his experience in China was that Japan should deal harshly with the Chinese population from the outset. As a result, the Chinese in Singapore were regarded as anti-Japanese even before the Japanese military landed.

In this and other senses, Japanese aggression in Southeast Asia was an extension of the Sino-Japanese War.

Fourth, among Japanese military officers and men there was a culture of prejudice toward the Chinese and other Asian people. These attitudes had deepened following the Sino-Japanese War of 1894-95 and were embedded within the Japanese population as a whole by the 1930s.

A final consideration is the issue of “preventive killing”. In Japan, preventive arrest was legalised in 1941 through a revision of Chian Iji Ho [Public Order Law], which allowed communists and others holding dangerous thoughts to be arrested and held in custody even if no crime had been committed. A number of detainees were tortured to death by the police, notably the Tokko special political police. The Singapore Massacre bears a close parallel to this method of preventive arrest and summary execution.

Clearly, then, the Singapore Massacre was not the conduct of a few evil people, but was consistent with approaches honed and applied in the course of a long period of Japanese aggression against China and subsequently applied to other Asian countries. To sum up the points developed above, the Japanese military, in particular the 25th Army, made use of the purge to remove prospective anti-Japanese elements and to threaten local Chinese and others in order to swiftly impose military administration. However, Japanese violence proved counter productive. Strong anti-Japanese feelings were ignited in the local population and not a few younger people joined anti-Japanese movements. The result was that Japanese forces never succeeded in resolving these difficulties in the years prior to defeat in 1945.

Narratives of the Singapore Massacre in Postwar Japan

The Campaign to Undermine the War Crimes Trials in the 1950s

Although the Singapore Massacre generated scant interest among the Japanese people in the postwar era, there has been some discussion of the incident. Singapore Garrison Commander Kawamura Saburo published his reminiscences in 1952, at a time when Japan was recovering its independence.[28] This book contains his diaries, personal letters, and other materials. In one letter to his family, he expressed condolences to the victims of Singapore and prayed for the repose of their souls. The foreword to the book was written by Tsuji, who had escaped punishment after the war. For his part, Tsuji showed no regrets and offered no apology to the victims.

During the 1950s, the Japanese government, members of parliament, and private organisations waged a nationwide campaign for the release of war criminals held in custody at Sugamo Prison in Tokyo.[29] Both conservatives and progressives took part in the campaign, arguing that minor war criminals were victims of the war, not true criminals. A Japanese government committee was in charge of recommending the parole and release of war criminals to the Allied Nations. The committee’s recommendations are still closed to the public in Japan, but can be read in the national archives of the UK and USA.

As an example of the committee’s recommendations, in 1952 the British government was asked to consider parole for Onishi Satoru, who took part in the Singapore Massacre as a Kempeitai officer and was sentenced to life imprisonment by a British war crimes trial.[30] The recommendation says that the figure of 5,000 victims of the Singapore Massacre was untrue and that his war crimes trial had been an act of reprisal. Although this recommendation was not approved by the British government, it reflects the Japanese government’s refusal to admit that mass murder had occurred in Singapore.[31] Among many Japanese, the war crimes trials were, and still are, regarded as a mockery of justice, or victor’s justice.

Japanese Response to Accusations by Singaporeans in the 1960s

Beginning in 1962, numerous human remains dating from the Occupation were found in various locations around Singapore. Prolonged discussions between the Singaporean and Japanese governments relating to these deaths led to a settlement in 1967. This was reported in the Japanese press, but only as minor news. For example, the Nihon Keizai Shimbun quoted a Japanese official involved in the negotiations as saying that no executions by shooting occurred in Malaysia.[32] The Asahi Shimbun reported that it was hardly conceivable that the Japanese military committed atrocities in Indonesia and Thailand.[33] Another Asahi report criticized the Chinese Chamber of Commerce in Singapore for stoking hatred by propagating stories of barbarity by the Japanese military during the war.[34]

Personal mementoes of Singaporeans excavated during the 1960s and presently exhibited in the Sun Yat-sen villa

In 2003, the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs released documents relating to the negotiations between Singapore and Japan during this period.[35] The Japanese government had made use of a report prepared in 1946 by an army committee chaired by Sugita Ichiji, a staff officer with the 25th Army. To counter war crimes charges, the report admitted that there had been executions, but insisted that there were mitigating circumstances.[36]

The figure of 5,000 executions, according to a written opinion by an official at the Ministry of Justice who was in charge of detained war criminals, was an exaggeration: the correct figure might be about 800. The Asahi Shimbun reported this number with apparent approval.[37] Additional figures come from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which accepted that the Japanese military had carried out mass killings in Singapore, but some Japanese foreign ministry documents state that the number of victims was 3,000, while others use 5,000. One ex-foreign ministry official sent a letter to the Foreign Minister saying that Japan should repent and apologize in all sincerity, but this attitude was exceptional among officials.

Changi Beach, site of largescale executions

During negotiations with Singapore, the Japanese government rejected demands for reparations but agreed to make a “gesture of atonement” by providing funds in other ways. What the Japanese government feared most was economic damage as a result of a boycott or sabotage by the local Chinese should Singapore’s demands be rejected. The agreement with Singapore was signed on the same day as a similar agreement with Malaysia. Singapore was to receive 25 million Singapore dollars as a gift and another 25 million Singapore dollars in credit, while Malaysia was to receive 25 million Malaysia dollars as a gift.[38]

To the last, the Japanese government refused to accept legal responsibility for the massacre or to carry out a survey of the deaths. The mass media in Japan did not examine what had happened in Singapore and Malaya during the war. It is no exaggeration to say that the Japanese media at that time showed no inclination to confront Japan’s war crimes or war responsibility.

Publications in the 1970s

There were, however, some honest responses in subsequent years. In 1967 Professor Ienaga Saburo, famous for his history textbook lawsuit against the Japanese government, published a book entitled The Pacific War that dealt with the Singapore Massacre.[39] In 1970, the monthly journal Chugoku [China] published a feature called, “Blood Debt: Chinese Massacre in Singapore”, the first extended treatment in Japan of the Singapore Massacre.[40] The piece was mostly written by Professor Tanaka Hiroshi.

The 1970s also saw publication of reminiscences by some of those directly involved in the Massacre, and by people who witnessed or heard about it, including Nihon Kempei Seishi [The Official History of the Japanese Kempeitai] by the Zenkoku Kenkyukai Rengokai [Joint Association of National Kempei Veterans],[41] Kempei by Otani Keijiro, and Hiroku Shonan Kakyo Shukusei Jiken [Secret Memoir of Singapore Overseas Chinese Purification] by Onishi Satoru. Onishi Satoru was a Kempeitai section commander who took part in the Massacre. In his book Onishi admitted that the “purification” was a serious crime against humanity, but he claimed that the number of victims was actually around 1,000.[42] Otani’s book severely criticizes the Japanese military, denouncing the “purification” as an act of tyranny and criticizing it from a human perspective.[43]

Although veterans’ associations usually justify or deny that inhuman acts had taken place, the Joint Association of National Kempei Veterans has admitted that the massacre was an inhuman act.[44] A few writers who were stationed or visited Singapore during the war have also published memoirs in which they record what they had heard about the Singapore Massacre.[45] On the whole, nobody denied that the Japanese purge in Singapore was an atrocity against humanity and historians began to pay attention to the episode. However, it failed to catch the attention of the Japanese people.

Research in the 1980s and 1990s

The situation changed in 1982, when the Ministry of Education ordered the deletion of passages relating to Japanese wartime atrocities in Asia from school textbooks, and instructed textbook writers to replace the term “aggression” with less emotive terms, such as “advance”.[46] This decision was severely criticized both at home and abroad, and a growing number of historians began to conduct research into Japanese atrocities, including the Nanjing Massacre.[47]

In 1984, while the textbook controversy continued, a bulky book called Malayan Chinese Resistance to Japan 1937-1945: Selected Source Materials was published in Singapore. Sections of this volume were translated into Japanese in 1986 under the title Nihongun Senryoka no Singapore [Singapore under Japanese Occupation], allowing Japanese to read in their own language Singaporean testimony concerning wartime events.[48] The main translator was Professor Tanaka Hiroshi, mentioned earlier as the author of a magazine article on the Singapore Massacre.

Another significant publication was a 1987 booklet by Takashima Nobuyoshi, then a high school teacher and now a professor at Ryukyu University, entitled Tabi Shiyo Tonan-Ajia E [Let’s travel to Southeast Asia].[49] Based on information Takashima collected during repeated visits to Malaysia and Singapore beginning in the early 1980s, the booklet discussed atrocities and provided details of the “Memorial to the Civilian Victims of the Japanese Occupation” and of an exhibition of victim mementos at the Sun Yat-sen Villa. The volume served as a guidebook for Japanese wishing to understand wartime events or visit sites of Japanese atrocities. In 1983 he began organising study tours to historical sites related to Japanese Occupation and to places where massacres occurred in Malaysia and Singapore.

In 1987, I located official military documents in the Library of the National Institute for Defense Studies, Defense Agency that included operational orders and official diaries related to the massacre of Chinese in Negri Sembilan and Malacca in 1942. Newspapers throughout Japan reported these findings, the first time that public attention focused on the killings in Malaya.[50] The documents revealed that troops from Hiroshima had been involved in atrocities in Negri Sembilan and this information came as a major shock to the people of Hiroshima, who had thought themselves as victims of the atomic bomb and had never imagined that their fathers or husbands had been involved in the massacres in Malaya.[51]

In 1988, several citizen groups jointly invited Chinese survivors from Malaysia to visit Japan, and staged meetings where Japanese citizens listened to their testimony. A book that included these statements was published in 1989. [52] Also in 1988, the Negri Sembilan Chinese Assembly Hall published a book in Chinese called Collected Materials of Suffering of Chinese in Negeri Sembilan during the Japanese Occupation, and the following year Professor Takashima and I published a Japanese translation of this volume.[53] Another source of information was the history textbook used in Singapore by students in junior high school, Social and Economic History of Modern Singapore 2, which was translated into Japanese in 1988. The material concerning the occupation attracted the attention of Japanese readers, particularly teachers and researchers.[54]

As might be expected, there was a backlash to these initiatives. It was claimed that Japanese troops killed only guerrillas and their supporters, and that the number was much smaller than reported. Responding to these allegations, I published a book in 1992 entitled Kakyo Gyakusatu: Nihongun Shihaika no Mare Hanto [Chinese Massacres: The Malay Peninsula under Japanese Occupation][55] that substantiated in detail the activities of the Japanese military in Negri Sembilan during March 1942, when several thousand Chinese were massacred. Since then there has been no rebuttal by those who would not concede the massacres in Malaya apart from personal attacks and contesting of trifling details that have no effect on the central argument.[56]

In 1996, the Singapore Heritage Society’s book, SYONAN: Singapore under the Japanese, 1942-1945 was translated into Japanese.[57] This book comprehensively introduced Japanese readers to the living conditions and suffering of Singaporeans under the Japanese occupation. Further information appeared in a book I published entitled, Sabakareta Senso Hanzai: Igirisu no Tainichi Senpan Saiban [Tried War Crimes; British War Crimes Trials of Japanese]. This volume contains an account of the Singapore Massacre based on British, Chinese and Japanese documents.[58]

The Rightist Backlash and the School Textbook Issue Since 2000

In the 1990s, some Japanese high school history textbooks began to provide information on the massacres in Singapore and Malaya, although they devoted only one or two lines to the events. More recently, chauvinistic campaigns and sentiment have become rampant in Japan. A number of ultra right books now claim that the Nanjing Massacre is a fabrication, that the Japanese military took good care of comfort women, and so on. Under pressure from the Ministry of Education, the Liberal Democratic Party, and other neo-nationalists, statements in school textbooks about Japanese atrocities have become less common, and the Minister of Education said in 2004 that it was desirable that descriptions of Japanese atrocities be dropped.[59] Moreover, teachers who explain Japanese aggression and army atrocities are often subjected to criticism by local officials or municipal education boards.

Descriptions of the Singapore massacre in high school history textbooks are particularly rare. According to research in the 1990s, just 8 out of a total of 26 textbooks mentioned the event.[60] The most widely used textbook states simply that “atrocities took place in Singapore and elsewhere”.[61] Other textbooks say that the Japanese army massacred tens of thousands of overseas Chinese in Singapore and Malaya, but even these descriptions are limited to one or two lines, and give no details. Anyone who dared set a question about the atrocities for a university entrance examination could expect attacks not only from right-wingers but also from MPs belonging to the ruling Liberal Democratic Party.

The situation is similar with regard to junior high school history textbooks. In the eight textbooks approved by the Ministry of Education in April 2005 for use from 2006, descriptions of Korean forced labor have all but disappeared, as has the term “comfort women”. Overall, references to Japanese aggression and atrocities have been drastically reduced under pressure from the Ministry of Education, the Liberal Democratic Party, and the right-leaning mass media. If the current ultra-nationalistic trend continues, it seems likely that even the few descriptions of the Singapore massacre that do exist will be eliminated.

Civilian War Memorial in War Memorial Park, Singapore

Conclusion

Work by Singaporean and other researchers has produced valuable information about the Singapore massacre, yet it seems to me that there is room for further research. In particular, what seems lacking is collation of documents in English, Chinese, and Japanese. While Singapore citizens have accounts of the Massacre and the suffering caused by the Japanese occupation, students in Japan are unable to imagine what happened in Singapore and Malaya during the Japanese Occupation. Few Japanese students have any opportunity to learn about the Occupation, and the many Japanese who visit Singapore each year generally are unaware of the killings or of the wartime suffering of Singaporeans. It is difficult to redress the balance, but if Japan is to achieve full reconciliation with the people of Singapore and other Southeast Asian countries and gain their trust, steps in the right direction must be taken.

Hayashi Hirofumi is professor of politics at Kanto-Gakuin University and the Co-Director of the Center for Research and Documentation on Japan’s War Responsibility. His books include Okinawasen to Minshu (The Battle of Okinawa and the People), Otsuki Shoten, 2001 and Ianfu, Senji Seiboryoku no Jittai: Chugoku, Tonan-Ajia, Taiheiyo Hen (The Comfort Women and Wartime Sexual Violence: China, Southeast Asia and the Pacific), Ryokufu Shuppan, 2000. He wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: Hayashi Hirofumi, “The Battle of Singapore, the Massacre of Chinese and Understanding of the Issue in Postwar Japan” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 28-4-09, July 13, 2009.

See also, Hayashi Hirofumi, “Government, the Military and Business in Japan’s Wartime Comfort Woman System,” The Asia-Pacific Journal.

[a] Kakyō Shukusei (華僑粛正)

[b] Dai Kenshō (大検証)

[c] Sook Ching (肃清- Purge)

[1] The Japanese term “Shukusei” was used by the Japanese Army at the time. In the Chinese community of Singapore it is usually called “Sook Ching” (mandarin “Suqing”).

[2] For details on the decision-making in the 25th Army, see Hayashi Hirofumi, Sabakareta Sensō Hanzai [Tried War Crimes: British War Crimes Trials of Japanese](Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1998) and ‘Shingaporu Kakyō Shukusei [Massacre of Chinese in Singapore]’ Nature-People-Society: Science and the Humanities, Kantō-Gakuin University, No.40, Jan. 2006.

[3] Kawamura’s diary is preserved in the National Archives of the UK in London.

[4] This document is preserved in the Library of the National Institute for Defense Studies [LNIDS], Defense Agency, Tokyo.

[5] For example, Singapore Heritage Society, Syonan: Singapore under the Japanese 1942-1945 (Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society, 1992), National Archives of Singapore, The Japanese Occupation, 1942-1945 (Singapore: Times, 1996), p. 72.

[6] For example, National Archives of Singapore, The Japanese Occupation, 1942-1945, p. 68.

[7] The operational order of the 25th Army and the order of the 5th Division dated 21 February 1942 in LNIDS.

[8] In this trial seven officers were prosecuted. Among them two were sentenced to death, while other five were sentenced to imprisonment for life. This is one of most famous war crimes trials held by the British in Singapore.

[9] “Kakyō Kōsaku Jisshi Yōryō [Implementation Guidance for Manipulating Overseas Chinese]” in LNIDS.

[10] Onishi Satoru, Hiroku Shonan Kakyo Shukusei Jiken [Secret Memoir Overseas Chinese Massacre in Singapore] (Tokyo: Kongo Shuppan, 1977), p. 69 and p. 78.

[11] This claim is prevalent among researchers in Japan. It is believed even by those who are not right-wingers. I have not clarified who put forward this reason for first time.

[12] The Dalforce file in “British Military Administration, Chinese Affairs, 1945-1946” (National Archives of Singapore).

[13] Numerous books contain such assertions, particularly books in Chinese.

[14] Rikujo Jieitai Kanbu Gakko [Ground Staff College, Ground Self-Defense Force], Mare Sakusen [The Malay Campaign] (Tokyo: Hara Shobo, 1996), pp. 240-1.

[15] Ōnishi, Hiroku Shonan Kakyō Shukusei Jiken, pp. 87-8.

[16] Furyo Kankei Chōsa Chuō Iinkai [Central Board of Inquiry on POWs], “Shingaporu ni okeru Kakyō Shodan Jōkyō Chōsho” [Record of Investigation on the Execution of Overseas Chinese in Singapore], 23 Oct. 1945 (Reprinted in Nagai Hitoshi (ed.), Sensō Hanzai Chōsa Shiryō [Documents on War Crimes Investigation] (Tokyo: Higashi Shuppan, 1995).

[17] See Hayashi Hirofumi, Sabakareta Senso Hanzai, p. 224.

[18] Otani Keijiro, Kenpei [The Military Police] (Tokyo: Shin-Jinbutsu Oraisha, 1973), p. 189.

[19] Ōnishi, Hiroku Shonan Kakyō Shukusei Jiken, p. 86.

[20] The intelligence files on Tsuji are preserved in Boxes 457 and 458, Personal Files of the Investigative Records Repository, Record Group 319 (The Army Staff), US National Archives and Records Administration.

[21] Asada Kyoji and Kobayashi Hideo (eds.), Nihon Teikokushugi no Manshu Shihai [Administration of Manchuria by the Japanese Imperialism] (Tokyo: Jicho-Sha, 1986), p. 180.

[22] See Ōnishi, Hiroku Shonan Kakyō Shukusei Jiken, pp. 88-92.

[23] Bōeichō Bōei Kenkyusho Senshi-bu [Military History Department, National Defense College, Defense Agency], Hokushi no Chian-sen, Part 1 [Security Operation in North China] (Tokyo: Asagumo Shinbunsha, 1968), pp. 114-30.

[24] See Chalmers Johnson, Peasant Nationalism and Communist Power. The Emergence of Revolutionary China, 1937-1945 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1962), pp. 55-58; Yung-fa Chen, Making Revolution: The Communist Movement in Eastern and Central China, 1937-1945 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), pp. 98-116; Edward Friedman, Paul G. Pickowicz and Mark Selden, Chinese Village, Socialist State (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991), pp. 29-51.

[25] Kojima Jo, Shisetu Yamashita Tomoyuki [Historical Narrative Yamashita Tomoyuki] (Tokyo: Bungei Shunjusha, 1969), p. 325. See also Yuki Tanaka, “Last Words of the Tiger of Malaya, General Yamashita Tomoyuki,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, September 22, 2005.

[26] Kawamura’s diary. See also Hayashi, Sabakareta Senso Hanzai, p. 220.

[27] See Akashi Yoji, “Watanabe Gunsei” [Military Administration by Watanabe], in Akashi Yoji (ed.), Nihon Senryōka no Eiryo Mare Shingaporu [Malaya and Singapore under the Japanese Occupation, 1941-45] (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2001).

[28] Kawamura Saburo, Jusan Kaidan wo Noboru [Walking up Thirteen Steps of Stairs] (Tokyo: Ato Shobo, 1952).

[29] See Hayashi Hirofumi, BC-kyu Senpan Saiban [Class B & C War Crimes Trials] (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 2005), ch. 6.

[30] FO371/105435(National Archives, UK).

[31] He was released in 1957.

[32] Nihon Keizai Shimbun, 3 Nov. 1966.

[33] Asahi Shimbun, 20 Sept. 1967.

[34] Asahi Shimbun, 18 Sept. 1963.

[35] These documents are open to the public at the Diplomatic Record Office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

[36] See footnote no.14.

[37] Asahi Shimbun, 29 Sept. 1963.

[38] Hara Fujio, “Mareishia, Shingaporu no Baishō Mondai” [Reparation Problem with Singapore and Malaysia], Sensō Sekinin Kenkyu [The Report on Japan’s War Responsibility], No. 10, Dec. 1995.

[39] Ienaga Saburō, Taiheiyō Sensō [The Pacific War] (Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1967).

[40] “Kessai: Shingaporu no Chugokujin Gyakusatsu Jiken” [Blood Debt: Chinese Massacre in Singapore], in Chugoku [China], vol. 76 (Mar. 1970).

[41] Tokyo: Private Press, 1976.

[42] Ōnishi, Hiroku Shonan Kakyō Shukusei Jiken, pp. 93-7.

[43] Otani Keijirō, Kempei, p. 189.

[44] Zenkoku Kenyukai Rengōkai, Nihon Kempei Seishi, p. 979.

[45] For example, Terasaki Hiroshi, Sensō no Yokogao [Profile of the War] (Tokyo: Taihei Shuppan, 1974), Nakajima Kenzo, Kaisō no Bungaku [Literature of Recollection], vol. 5 (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1977), Omata Yukio, Zoku Shinryaku [Sequel: Aggression] (Tokyo: Tokuma Shoten, 1982), and so on.

[46] See Rekishigaku Kenkyukai [The Historical Science Society of Japan], Rekishika wa naze Shinryaku ni kodawaruka [Why Historians adhere to Aggression] (Tokyo: Aoki Shoten, 1982).

[47] Composed of historians and journalists, Nankin Jiken Chōsa Kenkyu Kai [The Society for the Study of Nanking Massacre] was established in 1984. It remains active, although the scope of research has been extended to Japanese atrocities in China and the rest of Southeast Asia.

[48] Tokyo: Aoki Shoten, 1986.

[49] Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1987.

[50] This article was prepared by the Kyodo News Service and appeared in newspapers on 8 Dec. 1987.

[51] As mentioned before, the 5th Division conducted purges throughout the Malay Peninsular except Johor. The headquarters of the Division in peacetime was situated in Hiroshima and soldiers were conscripted in Hiroshima and neighboring prefectures.

[52] Sensō Giseisha wo Kokoro ni Kizamukai [Society for Keeping War Victims in our Heart], Nihongun no Maresia Jumin Gyakusatu [The Massacres of Malaysian Local Population by the Japanese Military] (Osaka: Toho Shuppan, 1989).

[53] Originally published in 1988. The Japanese translation was as follows: Takashima Nobuyoshi & Hayashi Hirofumi (eds.), Maraya no Nihongun [The Japanese Army in Malaya] (Tokyo: Aoki Shoten, 1989).

[54] Ishiwata Nobuo and Masuo Keizo (eds.), Gaikoku no Kyōkasho no nakano Nihon to Nihonjin [Japan and Japanese in a Foreign Textbook] (Tokyo: Ikkosha, 1988).

[55] Tokyo: Suzusawa Shoten, 1992. For arguments of right-wingers, see Chapter 8 of this book.

[56] See, for example, two articles by Hata Ikuhiko in the journal Seiron, August and Oct. 1992 and Professor Takashima’s and my responses in the same journal in Sept. and Nov. 1992.

[57] Tokyo: Gaifusha, 1996.

[58] Tokyo: Iwanami Shoten, 1998.

[59] See Hayashi Hirofumi, “Nihon no Haigaiteki Nashonarizumu wa Naze Taitō shitaka” [Why Japanese Chauvinistic Nationalism has gained strength] in VAWW-NET Japan (ed.), Kesareta Sabaki: NHK Bangumi Kaihen to Seiji Kainyu Jiken [Deleted Judgment: Interpolation of the NHK TV Program and the Politicians’ Intervention] (Tokyo: Gaifusha, 2005).

[60] Zenkoku Rekishi Kyōiku Kenkyu Kyōgikai [The National Council for History Education] (ed.), Nihonshi Yōgo-shu [Lexicon of the Japanese History Textbook] (Tokyo: Yamakawa Shoten, 2000), p. 291.

[61] Shōsetsu Nihonshi [The Details of Japanese History] (Tokyo: Yamakawa Shoten, 2001), p. 332.