The New Guinea Comfort Women, Japan and the Australian Connection: out of the shadows

Hank Nelson

Japan’s Prime Minister Abe Shinzo, determined to promote Japan as (in the words of his book) a “beautiful country,” whose school students will be taught to love it and whose citizens will be offered a version of its history in which they can take pride, finds himself in the incongruous position of sinking deeper and deeper into a shameful mire over his refusal to accept state responsibility for the mass mobilization of women for the sexual slave services for the Imperial Japanese Army during the Asian and Pacific wars to 1945.

From late in 2006, his running dispute with neighbor countries, China and South Korea, on this issue evolved into something even more serious, and apparently for him unexpected, a dispute with the government of the US. The House International Relations Committee, headed by Michael Honda, in January tabled a resolution calling on Japan to apologize unequivocally and unconditionally, compensate the surviving women, and educate present and future generations in the shameful truth of the “Comfort Women” system. In February it conducted a special sitting at which three representative women testified. The government of Japan has done its best to block the Honda Committee, but those efforts, and Abe’s tortuous and contradictory efforts to maintain his denialist stance but somehow also abide by the 1993 Japanese government statement accepting responsibility (the Kono Statement) may have been counter-productive.

The Japanese Prime Minister seems most concerned not to offend the Bush administration. Thus the incongruous spectacle of him in Washington offering to President Bush a carefully-worded expression of regret about the Comfort Women, which President Bush in turn “accepted” and praised, as if he somehow represented the women whom Abe steadfastly has refused to meet and whom he apparently views as liars.

US President George Bush and Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo

in Hanoi November 18, 2006.

Abe’s denialism rests on his insistence that there are no official records of direct state responsibility, ignoring the fact that the Japanese Diet in the 1990s actually compiled a considerable file of such records, and denying the legitimacy of the direct testimony of the women on many occasions in the past sixteen years. Yet evidence from many points of the old Japanese empire keeps coming to light to contradict him.

The Rabaul story is one of the least-known episodes in this sorry story. Here, prominent Australian historian of the Pacific, Hank Nelson, delves into the archival and memoir literature to reconstruct an astonishing story: the logistically massive Japanese state effort to transport, organize, supervise, and supply some 2,000 women in sexual service stations for its occupying forces, an operation that began almost from the day in 1942 when Rabaul, on New Britain Island at the remotest New Guinea fringe of the Japanese empire, fell into their hands. The Rabaul evidence amply documents the central role of the Japanese military in establishing, managing, and creating regulations to govern the comfort stations, which were established in Rabaul within weeks of its capture by Japanese forces in early 1942.

This is a story that illuminates more than the nature of the comfort women phenomenon in the Pacific, one involving Korean, Chinese, Taiwanese and Japanese women. It also offers important insight into racial hierarchies involving Australians, Japanese and New Guineans, and class (rank) hierarchies within the Japanese military.

Since Australian Prime Minister John Howard in March 2007 joined Mr. Abe in declaring that the two countries shared “democratic values, a commitment to human rights, freedom and the rule of law,” perhaps, with the publication of this evidence, the movement to demand Japan face the truth over the “Comfort Women” system will open a new, Australian, front, alongside Korea, China, the US and Canada. (GMcC, Japan Focus)

The Consolation Unit: Comfort Woman at Rabaul

From late 1942 Australians knew that the Japanese had shipped women to Rabaul where they worked in brothels catering for Japanese troops. Japanese captured on the Kokoda Track and elsewhere described the brothels, and New Guineans who had been in Rabaul talked about them. Australian military and civilian prisoners saw the brothels, and a few of those Australians observed them over a long period. Japanese who served in Rabaul have left reminiscences about the brothels and one Korean woman has testified that she worked in Rabaul. As a result, there is scattered material on perhaps 3000 comfort women in an Australian Territory, but when Australian reporters and commentators need to give the comfort women an Australian relevance, these women are never mentioned. Their experiences are not used to provide evidence on the recurring debates about whether the comfort women were coerced or free and whether they were recruited, shipped and employed by private contractors rather than the Japanese military or government.

Japanese marine attack Rabaul in 1942.

—————————————————–

As Prime Ministers John Howard and Abe Shinzo met in March 2007 to sign a security pact, questions about Japan’s role in World War II, its national memory of that war, and its willingness to admit to, and apologise for, atrocities all resurfaced.[1] Clint Eastwood’s two films, Flags of Our Fathers and Letters from Iwo Jima, a Japanese documentary aiming to show that the rape of Nanking was enemy propaganda, questions about official visits to the Yasukuni shrine which presents its own perspective on war and houses the spirits of convicted war criminals; the (predictable) failure of the teams of Japanese and Chinese scholars to reconcile two national histories; and the problem of the Japanese recognising its own victims of war while it is yet to accept its responsibility for making others victims have sharpened concern about how the Japanese present their own history.[2] And renewed interest by the American congress in the comfort women and the suggestion by Abe that the women were not compelled to work as prostitutes and the military did not have direct responsibility for the women ensured that the harrowing memories of the comfort women were again news.[3] To establish relevance, the Australian media turned to Jan Ruff-O’Herne who grew up in the Dutch East Indies and in the postwar married a British serviceman, Tom Ruff. In 1960, the Ruff-O’Herne family migrated to Australia. The first European woman to break her silence, Jan Ruff-O’Herne first told her daughters in 1992 and then gave testimony in Tokyo about suffering brutal serial rape in the House of the Seven Seas in Java. [4] But in all the Australian reports on comfort women there was no mention that ‘Consolation Units’ had operated for two years in Rabaul – in what had been the capital of the Australian Mandated Territory of New Guinea. Whether by accident or design, Australians have chosen not to remember the brothels in an Australian territory and not to use evidence from Rabaul to contribute to debates about the comfort women.

From late 1942 the Australians were advancing on the Kokoda Track and they began picking up Japanese prisoners. Determined to fight to the last, many, like First Class Private Miyaji Chihara, were starved, wounded and unconscious when captured.

Interrogated by the few Allied interpreters then available, most of the prisoners spoke freely. The Australians were keen to find out what had happened to over 1000 Australian soldiers and civilians captured in Rabaul, and Miyaji said he had seen them labouring on the wharves – as indeed they had been.[5] He also said that there were brothels in Rabaul where Japanese and Korean women were working. Another prisoner, Superior Private Arita Kazo, an old soldier who had first been called up in 1933 and had fought in China, said that in fact there were four brothels in Rabaul.[6] When the Allied Interpreter and Translation Section consolidated its reports in March 1945 it quoted Japanese prisoners saying variously that there two brothels in Rabaul and a more detailed claim from Superior Private Aoki Yoshio who said that there were twenty, five of them in the Kokopo area, but they were mainly used by officers and the men from the ranks rarely got a turn.[7] The differences in numbers of brothels may be explained by the prisoners being in Rabaul at different times, or having different levels of knowledge or no care for truth when talking to their enemies. They may well have given false names.

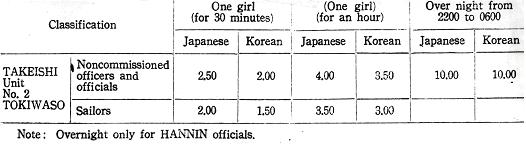

The Allied interpreters had also been presented with two documents from the Japanese 15 Anti-Aircraft Defence Unit on the Rabaul navy brothels (‘special warehouses’) setting out times, fees and the code of behaviour:

4. The drinking of liquor within the special warehouse is forbidden.

5. Those who seek pleasure will purchase tickets at the window and exchange them for ‘B’ tickets with the hostesses.

6. Hostesses will refuse pleasure to those who do not use prophylactic rubbers.

7. Each man must carry his own prophylactic rubbers. (In case of shortages at the canteens, there are some at the brothel for sailors of the unit at ten sen per package.)

8. The uniforms of petty officers and sailors, when entering and leaving special warehouses, will be dress uniform.

9. Violations of any of the above regulations by the hostesses will result in the withdrawal of their right to practice.[8]

The rates in yen were set out in a table:[9]

The racial discrimination that meant a Korean woman was cheaper than a Japanese, was strangely not applied to officers who chose to have one woman overnight.

Late in 1942, New Guineans who had been conscripted in Rabaul to work for the Japanese force that fought from Buna through Kokoda escaped or were liberated by the advancing Australians. Questioned by men from the old New Guinea service, three New Guineans who fled during an air raid said with some glee that the Japanese had recruited police from sanitation line – the men who had carried the cans from Rabaul’s outside dunnies (toilets). And they said that there was a Japanese brothel in Chinatown, on the northeast of central Rabaul.[10]

After the Americans landed on southern New Britain at the end of 1943 and Australian troops and coastwatchers pushed closer to Rabaul, the Australians were able to talk to other people who been in Rabaul. Peter Kyllert, a Swede and his German-born wife, had decided to stay on their plantation, a short sail out of Rabaul on New Britain’s west coast. But his status as neutral and his wife’s as an ally had won him few favours with the Japanese. By 1944 he was ill and was relieved when the coastwatchers picked him up in September. Kyllert had been into Rabaul in the early months of the Japanese occupation, and later mixed race and New Guinean people leaving Rabaul had passed through his plantation. He brought disturbing rumours about the fate of Australian prisoners, and that New Guineans were behaving in ways unthinkable in prewar Rabaul with its strict distinctions between races. He said that after the first few months when many New Guineans had gone bush, they were drifting back to Rabaul.

One of the main reasons why the natives were anxious to go into Rabaul was because women imported by the Japanese to satisfy the physical desires of their troops were also available for the natives. A quaint custom adopted by many of these women was to allow the natives to fondle them, have intercourse and assist in bathing them.[11]

The lure of Rabaul was probably increased by rumour and male fantasy – the job description looks like those other fantasies such as the brewery that wanted beer tasters – but the New Guineans who saw the white prisoners working under Japanese guards, copping the occasional kick or slap, scrounging for food, and making their own tea had entered a world inconceivable before January 1942.[12]

One New Guinean who had actually worked at a brothel gave a more prosaic account. Chouka of Manus had been ‘boss boy’ for Rod Marsland on Lagenda plantation near Talasea and stayed there for fourteen months after Marsland left in March 1942. In Rabaul, the Japanese told Chouka that either he worked or he went to gaol. He was sent to crew a fishing schooner but deserted:

I then went and worked for the GEISHA girls in Chinatown. Some were Japanese girls, but the majority were Koreans. I was used as general labourer and cut wood etc. We were not allowed to consort with the girls and they appeared to be under the control of the Military Police. During the day time the soldiers regularly visited the brothels all day long and at night only the girls’ particular friends slept there all night.[13]

Chouka said there were ‘plenty’ of women; and he knew of seven brothels in Rabaul and one in the Catholic Father’s house at Kabaira a few miles to the west of Rabaul. For his labour, Chouka was paid five shillings a month (the minimum wage under the prewarAustralian administration). He could spend his shilling invasion notes in a Japanese store, but demand always exceeded the supply of goods, and no rice, tinned meat, knives or axes were ever available. Chouka and others escaped in a canoe from Rabaul and, travelling at night, reached Talasea and the advancing Australians in May 1944.[14] Chouka – and others – brought comfort to those Australians who feared the old, and proper, order had been destroyed, and that a precedent had put at risk the sanctity of white women.

From September 1945, the few Australians who had survived imprisonment in Rabaul were free to talk about what they had seen and heard. While Australians were determined to document Japanese atrocities, they showed little interest in the comfort women. Testimony about the women in the brothels was generally presented and received as exotic, evidence of the enemy’s curious immorality and Japanese commanders’ readiness to indulge the lust of their troops. Some Australian officers of Lark Force captured after the Japanese landing were shipped to Japan on the Naruto Maru in July 1942.[15] Few had kept diaries in the first months of captivity in Rabaul, but in Zentsuji in Japan they had more time and some reconstructed their time in Rabaul. Captain David Hutchinson-Smith of the 17th Anti-Tank Battery wrote the most detailed account. After a ‘deft cuff’ for failing to bow appropriately,

Hutchinson-Smith was asked a series of questions including several that surprised him: ‘Where were the women for the use of the officers and soldiers? Why did we not have them? Did we use the nurses? Why not?’[16] In frightening circumstances, that same assumption underlay the reception of the Australians nurses. On the day of their landing the Japanese lined up the Australian civilian and military nurses at Kokopo and as they had no doctor with them accused them of being there for the use of the troops. After standing ‘for an eternity’ with their hands in the air under the gaze of men pointing sub-machine guns at them, the nurses were told they would not be shot ‘today’.[17]

Hutchison-Smith says that Japanese women arrived about a week after the fall of Rabaul, and that:

I saw several taking a stroll with their officer friends in the late afternoon, wearing brightly-coloured kimono and obi (sashes). They affected elaborate hair styles and their faces were over-painted and over-powdered. They minced along on high-stilted wooden geta (sandals) and protected themselves from the sun with attractive oiled silk umbrellas in brilliant hues. The sight was a strange one as they clogged along with tiny, pigeon-toed steps, a few paces behind their lords and masters, here in the new southern stronghold.[18]

Later, Hutchinson-Smith said, he saw another and ‘more obviously seamy side’ of ‘Japanese service life’. A building between the Bank of New South Wales and the Crown Law Office – near the junction of Park Street and Mango Avenue – housed the women who provided sexual services for the lower ranks and labour units. It was just one of several buildings around town where the women worked. These ‘slaves’, Hutchinson-Smith claimed, were ‘of no particular breed. Some were dark, almost black, but with strange, partly Japanese features’. To Hutchinson-Smith these women were ‘filthy, revolting creatures’ and it was the plight of these women that made the Australian prisoners of war fear for the fate of the nurses.[19]

Captain John Murphy, captured on a coastwatching mission in 1943, was the only Australian military prisoner alive in Rabaul at the end of the war. Having served as a government officer in the civil administration of New Guinea in the prewar, he was on familiar ground. He was imprisoned in Chinatown in Ah Teck’s tailor’s shop where he had been fitted for his newest pair of civilian trousers.[20] In another Chinatown building they would sometimes see, Murphy said, the women of the ‘8th Consolation Unit’: a barefoot ‘frumpy lot’ they were unlike the painted geishas the prisoners expected. They flashed their bodies, beckoned and mocked the prisoners. An American pilot imprisoned with Murphy, Joseph Nason, recalled that one day as the prisoners were returning from a work site, a guard, Okano, called the women: ‘One of the girls leaned over the balcony and squealed, “Fuckee, fuckee!” with appropriate gestures of her hand’ but the prisoners in their weakened state had no capacity to respond, let alone overcome what other moral and practical inhibitions might have restrained them. Seeing the lack of response, one of the women ‘coyly drew back her kimono and displayed her sex. The other girls playfully tried to cover her up again, but their efforts resulted in even more exposure’.[21] Nason asked a quiet (and embarrassed guard) where the girls were from and he said they were from China and Korea. When asked if they came willingly, he claimed he did not know.

One night the prisoners heard a ‘wild disturbance’ and pistol shots coming from the direction of the ‘Comfort House’. Soon after, a brutally battered Japanese soldier was flung into their cell. That in itself was unusual: for a Japanese soldier to be so degraded that he was cast among prisoners of war meant that he had committed a gross violation of Japanese military law. The prisoners soon found that the soldier had died, but by leaving him propped up in a sitting position they were able to claim his rations for four meals. New Guineans were brought in to carry away the body. The prisoners were told that the dead soldier’s crime was trying to get into the Comfort House at a time when it was reserved for officers.[22]

After their first frightening confrontation with the Japanese assault troops, the Australian nurses were confined in one of the buildings of the Catholic mission at Vunapope, southeast of Rabaul. There they had had their faces slapped, evaded gauche attempts at fondling and knew that they were at risk: two Australian soldiers from the 2/10th field ambulance and some wounded men captured with them had been taken away and killed. Then, just after the fall of Singapore they had what they were to remember as ‘the Day of the Girls’. One morning after breakfast, they looked out to see ‘a moving mass of colour spreading from the lawn below … to the front of the cathedral. There were hundreds of these tiny women in bright kimonos flitting about like swarms of butterflies’.[23] The women waited while the mission brothers were removed from their quarters and then they moved in. The Japanese officers certainly knew that the building the women occupied had been the home of the celibate missionaries, many of them from Germany and Austria; but it is uncertain whether they selected the building as part of some extravagant humiliation of a religion, a race or an associate of imperialism or simply because it was one of the few buildings with many rooms and many beds. Alice Bowman, one of the civilian nurses who had worked in the prewar government service, said that all who could watched the strange scene unfolding before them. Amid much speculation about what it all meant, the nurses concluded that if the women met the sexual needs of the Japanese troops they would be under less pressure. Perhaps they were right: in June 1942 the seventeen army and civilian nurses and one civilian woman were shipped to Japan having suffered annoyance and threat but no severe beatings or sexual assaults.

Gordon Thomas had first gone to Rabaul in 1911 and he was one of only four civilians to have been in Rabaul on 23 January 1942 and to be still in the town area in August 1945.[24] Thomas had been editor of the Rabaul Times, and by inclination and profession he was a writer. Soon after he was interned, Thomas began keeping a diary and in the postwar he turned it into an account of his three and half years in Japanese-controlled Rabaul. His manuscript was never published. Thomas seems to have been retained and survived in Rabaul because he was sent to work as cook for three other civilians who were directed to operate W. R. Carpenter’s freezer.[25] Thomas and the prisoners often saw the comfort women and sometimes spoke to them. Japanese servicemen, particularly officers, would call at the freezer for ice, or just a glass of water containing ice. Many were accompanied by ‘their kimonoed ladies’.[26] Before Japanese troops left for battle, Thomas says, Rabaul was like Berlin, Paris, London and Rome in similar circumstances – it was ‘Wine, Women and Song’ and the ‘lassies let their hair down’.[27] At the freezer the men and women who wanted to party collected ice, raided the food stocks and got their beer cooled.

Some women came to the freezer without men: ‘the Little Ladies from the brothels swarmed round the place at every opportunity’.[28] After the ‘novelty wore off’, Thomas says, the prisoners came to ‘curse’ the women. Thomas had come to assert a grumpy proprietorship over the kitchen, and he resented the women taking over his utensils, his plates, his ingredients and his stove to cook their own ‘weird concoctions’ while listening to ‘screeching’ Japanese records on the gramophone.[29] Thomas records the names that the prisoners gave to two of the women, ‘Titzy’ and ‘Pearl’, whose visits and demands for ice water were so frequent that the Japanese instructed the prisoners to cut their supply.[30] Thomas described Titzy:

she was an unlovely looking wench, apparently from some very rural district in Korea, where they bred them fat and strong in the hocks, and particularly stupid….

Poor old Titzy! She must have been dumb, even in a professional way for, of all the harlots in Rabaul, she was the only one – so I was told – who had a baby, which of course died slightly after birth.[31]

He described one other woman:

There was one wizened up little Nip woman, who came regularly, usually during the day-time. She was a cook or caterer for several of the brothels and looked for all the world like a little monkey. I remember one day Mac [George McKecknie] studying her closely for a while, then turning with a smile remarked:

‘My God! No wonder she’s a cook’

‘I beg your pardon!’ I said, registering hurt dignity at my own calling being ridiculed.[32]

In making his disparaging remarks about the women, Thomas was picking up the vocabulary then used about Japanese soldiers; he – and other ex-prisoners – were reflecting anger at their own treatment and the cruelty they had seen inflicted on others; and they were unlikely to tell the public and their wives and girlfriends that they had found the comfort women attractive.

Gordon Thomas saw the comfort women arrive and he reported their leaving and fate. Before he was sent to be the cook at the freezer, Thomas was working with other civilian internees on labouring jobs around Rabaul. In the second week of his internment, Thomas was shifted from New Britain Timber’s saw mill in Malaguna to the wharf, and he was there when over 200 Korean women landed. He too noted the coloured kimonos, the ‘fancy “hair dos”’ and the clatter of the wooden shoes. The ‘Ladies of a Thousand Delights’ were:

Gay, chattering little bodies, laughing and running around like children. In fact many of them were little more than children. Our task consisted of loading their bundles and suit-cases from the deck of the vessel to lorries waiting near the wharf.

We carried out our task with our usual levity; laughing and joking like the proverbial clown, even though our hearts were breaking. The guards were experiencing quite a kick from seeing the lordly whites waiting upon women, which was about the lowest possible task for anyone in the East to be called upon to do.

My comrade in the line of prisoners carrying the luggage was a well-known and popular priest who, it was easy to see, was cracking hardy. The task over, we stood beside the lorries, wiping our brows when I heard the priest speaking in his broad Irish voice:

‘I wonder what His Holiness would say if he knew I was portering for prostitutes!’

The delightful brogue, the serious tone of his voice and the general situation tickled my fancy, and I burst out laughing…. For some time the ‘portering for prostitutes’ was the joke of the crowd.[33]

As in much of his writing of war and peace, Thomas was conscious of the preciousness of white prestige: it was at the centre of his beliefs about the proper ordering of colonial society. In Thomas’s ideal world, the whites acted as worthy, firm but fair overlords and other races accepted their lesser places. In that world, whites both deserved and demanded respect. Chaos and violence followed when the triumph of the undeserving and envious of other races seized power. This was always a threat and could happen quickly if the whites were lax or committed elsewhere – as they were by Hitler in World War II.

Thomas said that the women whose bags he carried were not the first to arrive, and in fact Thomas thought the first group had landed just a day after the invasion. Within three weeks, there were over 3000 of these ‘little ladies’ ashore and they were working at ‘top pressure’.[34] It might have been expected, Thomas speculated, that with most of the women working in Chinatown night and day, there would be brawling and rowdiness, but in fact queues and times were carefully regulated. Navy, air force and army were each allocated their separate establishments, the limit of one visit a fortnight was accepted and military police ensured good order. The one fight that Thomas saw and described in detail was between the women of neighbouring buildings in Chinatown. Several had their clothes torn off, and the brawl was eventually stopped by the military police who poured water on the fiery ‘Amazons’.[35] Officers, Thomas said, had exclusive access to separate brothels, some of which were on Namanula Hill, the top site overlooking the town and the harbour on the west and with views out to St George’s Channel on the east. Under the Australians, the administrator, two judges, two doctors and patients in the European hospital had enjoyed the breeze, space and views on Namanula: those Australians with less money and fewer pretensions drank at the Pacific and Cosmopolitan Hotels on the edge of Chinatown. The Japanese and Australians – and the Germans before them – made the same distinctions about space and privilege.

The women who worked on Namanula, Thomas said, were Japanese, but in Chinatown and along the harbour most of the women at the end of the queues meeting men from the ranks were Koreans. An ‘irate Korean’ told Thomas that they ‘were supposed to come south for the purpose of working in factories and on cacao and coffee plantations. Only on their arrival in Rabaul did they discover the real nature of their employment.’[36] To ensure that no reader thought he obtained his knowledge through experience, Thomas claimed he was ‘reliably informed’ that the Korean women were ‘handling’ about twenty-five to thirty-five clients a day. At that rate, Thomas calculated, they could meet the sexual needs of the 100,000 Japanese in Rabaul and of the crews of visiting ships, and that was why the local Asian women were ‘not molested by the invaders’.[37] A few of the comfort women, Thomas claimed, also catered for private clients for cash or other rewards.[38]

On 18 December 1943 Thomas wrote a note on what he could see through the wire screen on the prisoners’ sleepout at the freezer. The screen itself was now broken by bomb blast, the ceiling had fallen in and shrapnel and bullet holes marked the walls. Weeds had started growing on the protective earthworks, everywhere was evidence of the digging of deeper trenches, and:

Of late the number of men bound for the House of a Thousand Delights has diminished considerably, for these ladies are few now. They have been sent away for safety’s sake. Rabaul is no longer deemed a safe retreat…. Life has become wearisome; the unending sameness; the mental lassitude; the tension preying upon one’s nerves ….[39]

In his reminiscences, Thomas recalled the leaving of the last of the women. To cheers, they went down the street sitting on top of their bundles and cases. The last ‘splash of colour’ had gone from the town. There was, Thomas said, a ‘sad ending’: the ship carrying them was bombed a day out of Rabaul and only ‘half-a-dozen or so escaped to tell the tale’:

They had an unenviable task – regimented to amuse the troops; black-birded into prostitution; or perhaps it might be better termed Victims of the Yellow Slave trade. At any rate they were said to be pressed into service, not knowing to what they were coming. And they had done their job.[40]

For Thomas, that was a compassionate statement about the enemy, and he went on to observe that while the Korean women had suffered, the Japanese system of brothels was preferable to having thousands of troops force local women into compliance, depend on the ‘promiscuity of amateurs’, or enter ‘un-natural sex relations’.[41]

Some of the events that provide the background to Thomas’s descriptions can be confirmed. The Allied aerial assault on Rabaul intensified from a major raid of 12 October 1943 when 349 aircraft attacked airfields and shipping.[42] The attacks were part of the plan to neutralise Rabaul, rendering the Japanese forces there incapable of offensive action as the Allies landed at Torokina on Bougainville in November and the western end of New Britain in December. In November, carrier based aircraft joined the attack on Rabaul, and the destruction of nearly all buildings intensified. In February 1944, the Allies moved closer when they captured Nissan (Green) Island. The last of the Japanese cargo ships left Rabaul in February 1944, and where there had been up to 600 aircraft based in Rabaul in 1943, by the end of February 1944 nearly all Japanese aeroplanes had been destroyed or withdrawn.[43] When the Allies occupied Emirau Island to the north in March 1944 the encircling of Rabaul was complete and the Japanese forces were largely dependent on subsistence. While the 100,000 strong force could defend itself, it could not project its strength beyond Rabaul; it did not even offer an effective threat to Allied troops holding areas on other parts of New Britain.

Leaving at the end of 1943, the comfort women were taking some of the last ships to escape from Rabaul, and as Thomas heard, some left too late. The chances of ships getting through the Allied cordon of patrolling aircraft, surface ships and submarines were diminishing. On 30 November 1943, the Himalaya Maru left Rabaul carrying a total of 1,366 soldiers, wounded servicemen and ‘solace women’. Attacked by United States aircraft, the Himalaya Maru sank off New Hanover on 1 December, some survivors being picked up by other ships in the convoy.[44] A Japanese doctor has reported treating two women in Kavieng, the only comfort women to survive the sinking of a transport.[45] George Hicks in his general history of comfort women says that there are ‘accounts’ of women being taken from Rabaul to Guadalcanal, their ship being sunk and only a few able to swim ashore on Bougainville.[46] Something of the dangers involved in travel by sea can be gauged from the fact that in the last convoy of surface transports to leave Rabaul on 20 February 1944, two of the three transports were sunk on 21 February and the third, which had picked up survivors, was sunk on 22 February off Kavieng and so ‘the convoy and people aboard perished in the south sea’.[47]

In the postwar, many Japanese ex-servicemen have written reminiscences of the war in New Guinea, the number increasing from 1960.[48] Although few have been translated, some of those that have provide frank accounts of comfort women.[49] Watanabe Tetsuo was in the last stages of his medical degree when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbour. His graduation was brought forward, he was appointed a surgeon-sub-lieutenant, and in January 1943, having survived his first battles at sea, he and other officers (including petty officers) from the torpedo ship, Hiyodori, were in Rabaul.[50] Refused entry to a crowded restaurant, the captain took the officers to a commanders’ combined restaurant and brothel. That brothel became the resort of the Hiyodori ‘family’. One night during an air raid the bombs fell close:

At such times, one of the brothel’s women used to try to cover me with her body saying ‘I do not want a soldier to be hurt here.’ If the bomb had hit us directly, we would have both gone. I used to wonder if my death would have been filed as ‘killed in action’.[51]

The story may well be true, but the punch-line, ‘killed in action’ when in sexual embrace has been used about many soldiers in many campaigns. Watanabe says that at another ‘restaurant’ where about ten Japanese women worked, they included a mother and daughter.[52]

On his last visit to Rabaul late in 1943, Watanabe went to the officers’ ‘restaurant’ in the botanical gardens. He described Rabaul in words similar to those used by Gordon Thomas: it was then a ‘desolate town’, many buildings had been destroyed, few people moved in the streets and the harbour once crowded with shipping was being used by just a ‘couple of barges’. At the restaurant one of the women told him – correctly – Rabaul had been attacked by carrier-borne aircraft and that the women were soon to go back to Japan. Watanabe was posted to the mainland, and in August 1945 was one of the survivors on Kairiru Island off the Sepik coast.

Another naval surgeon, Igusa Kentaro, graduated from the Tokyo University Medical School, served on a battleship and then in land-based units, the 81st Guard Corps in Rabaul and the 83rd in Kavieng.[53] Arriving in Rabaul in February 1943, he was as a ‘newcomer’ assigned to inspect and treat the ‘Special Necessary Personnel’, the ‘SNP’, the ‘love girls or contract prostitutes’. In Rabaul, he was responsible for 110 women and, after he shifted to Kavieng in May, about thirty-two, all reserved for the navy. Some of the girls were accustomed to their work, but others were ‘from poor families and probably had boyfriends back home … and looked as pure as virgins’:

In the Navy, SNP were classified into four categories: those available to admirals, to high ranking officers, to low-ranking officers, and those available to enlisted men and non-commissioned officers. When I examined them [in Rabaul], these categories numbered five, twenty, thirty and fifty girls respectively. I had no way of knowing their birthplaces, but in Kavieng their numbers were smaller and their categories were no longer strictly divided as in Rabaul. They were available to enlisted men by day and to officers by night, sixteen girls constituting one group and each group being cared for by supervisors and their wives. The girls were from Wakayama and Okinawa Prefectures.[54]

The women, Igusa said, had to wash their genitals after each contact, and some of the inexperienced women were unable to do this effectively, and this, Igusa thought, may have been a reason why they became infected with venereal disease. Some were so badly swollen they ‘cried and begged for help’, but, Igusa claimed, the newly released sulpha drugs brought about quick cures. It appears that the women continued to work through times of infection and severe discomfort.[55]

On their regular weekly inspections, the women lay exposed on a table with a screen preventing the doctor and his orderly from seeing their faces. Igusa, who showed what is hoped was a professional interest in the women’s genitals, said that some of the ‘adolescent girls and young women’ trembled ‘probably from shame’.[56] Igusa ‘heard’ that ‘almost all of them’ died at sea when they were evacuated in early 1944.[57] The two that were brought ashore in Kavieng were returned to Rabaul, but whether they eventually got home is uncertain.[58]

There are claims of comfort women still living in New Guinea at the end of the war. One American report says that after Japanese troops pulled out of Mussau Island, Chinese and Korean women were abandoned there. Following the Americans landing on nearby Emirau, the women were rescued from ‘horrible’ conditions.[59] One of the first of the Korean women prepared to give public testimony in 1991, known by the pseudonym Lee Jin Hee or simply Plaintiff A, said that she had been conscripted from the family farm in 1942 under the ‘virgin delivery order’. She attempted to escape, but was picked up by other recruiters and shipped to Rabaul. After working for about ten days in a hospital laundry, she was forced to work as a comfort woman in a church. Taking advantage of the severe bombing, she was one of ten who escaped into the jungle and they lived by subsistence gardening. In their isolation, the escapees did not learn about the end of the war until some time after the event. She claimed to have been shipped home in about April 1946.[60] I have not seen any confirming evidence of Australian units collecting enemy women, and there are many references of patrols picking up Japanese soldiers and conscripted or volunteer labourers from India, China and Indonesia. But this does not mean that the report of the women on Mussau or Lee Jin Hee’s testimony is wrong, and Lee does give details consistent with her being in Rabaul.[61]

* * * * *

In the immediate postwar, the Australians were keen to find evidence of Japanese war crimes. Under the War Crimes Act of 1945, the Australians put some 924 Japanese on trial, 390 of them in Rabaul, although not all of them for crimes committed in the Rabaul area. Of the 644 who were found guilty, 148 were sentenced to death. In the preliminary enquiries and trials, the Australian investigators wanted evidence of crimes against Australians but they also considered crimes against Indian, Chinese and Indonesian men (nearly all of whom had been brought to New Guinea by the Japanese) and against New Guineans.[62] The Australians were not concerned about crimes by Japanese against Japanese or people from Japanese colonies. As most comfort women were from Korea and nearly all the rest were Japanese or Formosan, they were excluded from investigation. But there is some evidence of Chinese and Indonesian or Malay comfort women in New Guinea, and although the ‘Chinese’ might have been women from Formosa, there may well have been women who came within the Australian category of victims of war crimes.[63] The Australians made no use of the evidence that they had concerning the treatment of the women, and could have extended, and neither did any of the other victorious nations.

The enormity of the crime in Rabaul is difficult to calculate. The total numbers of comfort women vary greatly in the reports: the best informed of the foreigners, Gordon Thomas, says over 3000 while the normally authoritative United States Strategic Bombing Survey suggests ‘500-600’.[64] Given the many brothels, from Kabaira to Kokopo, and that there were said to be 253 Formosans alone, there were probably well over 600, but just how many is uncertain.[65] Again it cannot be known how many freely and knowingly chose to go to Rabaul, but it would have been a minority. What seems to have happened in Rabaul is that perhaps 2000 or more women were deceived and forced into prostitution of a most demanding kind – they were meeting the demands of men day and night. Many suffered injury and infection and few survived the journey home. The women sent to Rabaul to satisfy the sexual needs of Japanese servicemen probably had a higher death rate than any Australian unit that fought in World War II. Japanese military units suffered equal and greater casualties in the southwest Pacific, but not if they served exclusively in and around Rabaul.

Although the first comprehensive account of comfort women by Senda Kako was published in 1973, it was not until the early1980s that the question of their treatment began to engage the interest of a broad group of committed researchers.[66] By the end of the 1980s there was a growing movement, particularly among Korean and Japanese women, to force the Japanese public and government to acknowledge the forced prostitution of the women, the first comfort women had spoken, and a Japanese man engaged in the conscription of Korean labourers had written his reminiscences.[67] The experiences of the comfort women were widening into general issues of soldiers and rape – and civilians as sex tourists.[68] Interest quickened in 1991 and 1992 when the first Korean comfort women made public statements, initiated a court case in Japan, and the Prime Minister, Miyazawa Kiichi, apologised for the mistreatment of Korean women. It was then that Jan Ruff-O’Herne decided to go public after ‘fifty years of silence’. She arrived in Tokyo in December 1992 spoke on television and gave her testimony.[69] The comfort women had become an issue in Australia, but in spite of the fact that one of the Korean women, identified as Lee Jin Hee, spoke of her extraordinary experiences in Rabaul there were few attempts to draw on the material that Australians had collected since 1942, or to make the obvious point that the comfort women had worked on Australian territory and many had died in Australian territorial seas.

In the fifteen years since the comfort women became international news, the two most important publications that extend the discussion to Rabaul are George Hicks’ general history, The Comfort Women, 1995, and Peter Stone’s detailed history of the war in Rabaul, Hostages to Freedom, 1994.[70] Both Hicks and Stone provide three or four pages on comfort women in Rabaul, and although Stone appears to have been published after Hicks he has acknowledged drawing on Hicks’ material. It is a limited contribution to a major debate, and the academic historians have been missing. The most original work remains Noriko Sekiguchi’s documentary film, Senso Daughters, with its frank and lively interviews with New Guineans, but Sekiguchi had completed her work before the Korean women and Ruff-O’Herne had testified.

In the debates of March 2007, there was the usual confusion of the denial of a long-standing apology, then a re-affirmation, and a legacy of doubt. Prime Minister Abe initially appeared to deny that women were forced to work in military brothels and he would order a new study to establish the truth. In the face of international opposition, Abe ‘apologised here and now as the prime minister’ and he and other senior members of the government asserted that the 1993 statement made by Kono Yohei, then cabinet secretary, still stood.[71] The Kono statement acknowledges that the women were coerced and that the military were involved. Unfortunately, the sequence of events seemed to show senior members of the government acknowledging a wartime atrocity only when forced to do so. Similarly, the Japanese scheme to compensate comfort women is qualified: the Asian Women’s Fund was supported by the Japanese government but it was a private initiative. Through the debate, some Japanese continued to assert that there was no evidence to support anything more than opportunistic private contractors meeting the demands of hundreds of thousands of young men in military camps.

The various accounts of the deployment and exploitation of the women at Rabaul reinforces evidence from elsewhere and adds to understanding the system and the experience of those who endured it. Thomas says that a ‘brothel was in full swing’ within twenty-four hours of the landing.[72] Even if that is untrue, Thomas himself saw women arriving about a fortnight after the first troops came ashore; and the nurses and Hutchinson-Smith also report seeing them early.[73] The Japanese South Seas detachment had taken seven days’ sailing from Guam to lie off Rabaul by 22 January 1942 and the supporting force that had left from Truk had taken four days. If the first of the comfort woman arrived in Rabaul within three days of the Japanese landing then they were already at sea before the outcome of the landing was known. Even if the women did not arrive for two or three weeks – that is when seen by Thomas – this was a rapid deployment. Given the need for a quick build-up of forces, weapons and stores and the demand for space on early convoys, the comfort women must have been given a high priority. It is inconceivable that a private contractor would have responded within the time available and been given space on military transports for his business venture.

Rabaul was always an operating base for the Japanese. Major forces were leaving for the Coral Sea, Kokoda, Guadalcanal and mainland New Guinea, and from as early as May 1942 they were returning with casualties. By the end of the year they were returning with few survivors. Aircraft were taking off from four different airfields to attack the Allies, and Rabaul was always within range of Allied bombers. Aerial attacks on Rabaul were light in the early months of 1942, but Rabaul was bombed on the day after the Japanese landing, and bombing raids, often by just three or four aircraft at night, were frequent. Although complete Allied dominance of the air over Rabaul was not achieved until late 1943, occasional heavy raids were carried out in the second half of 1942.[74] Minseibu, the civil administration section, was not set up in Rabaul until 10 March 1942, and its activities were always subject to the prosecution of the war.[75] In Rabaul, the comfort women were not part of the service provided for men on leave – on rest and recreation as it would be termed in another war – they were always in some danger and the men they encountered were in units that may have been manning anti-aircraft guns a few hours earlier.

The evidence about the management of the brothels says explicitly or implicitly that they were controlled by the military.[76] The brothels in Rabaul were divided by service – army or navy – and time and choice of women varied with rank. The translated document from the 15 Anti-Aircraft Defence Unit with its detailed regulation of dress and behaviour and the listing of times and prices would be recognized by most ex-soldiers as a standard ‘routine order’ – except that is about attending a particular brothel. The doctors who inspected the women were commissioned officers and Igusa, writing before the debate became internationally significant, said – as though it was a simple matter of fact – that the women were sent to the ‘front by order of Vice Admiral Sawamoto Yorio, Vice Secretary of the Navy Ministry under Secretary Chief Admiral Hantaro Shimada’.[77] It is also true that there is evidence of non-military men and women managing brothels, but they were at a low level and working within a system which determined where the brothels were, who visited and when, and the amount – if anything – that was paid.

Both the Japanese and Australian descriptions of the behaviour of the women – from trembling modesty and innocence to flamboyant sexual aggression – indicate that some of the women were prostitutes before recruitment (or had become hardened to the work over time) while others were sexually inexperienced. Igusa makes a poignant comment on ‘naïve girls’ from the country who had left poor families and boyfriends at home and Thomas does not disguise his sympathy for the conscripted Koreans. The comments on some of the women out walking with their officer boyfriends may well be confirmation that some of the women were accustomed to a life in which they exchanged sex for favours in cash, kind and status. But one well-known survival ploy of women who face serial rape, destruction of their reproductive capacity and any chance of a successful married life is to cultivate a relationship with one man who has the power of personality and office to demand exclusive sexual possession. It is expressed most frankly by the anonymous author of A Woman of Berlin who knew that to get food and avoid being preyed on by drunk and sober Russians she had to form a liaison with an officer who was going to stay in the area and who had the authority to protect her.[78]

Observers asserted that the presence of the comfort women protected other women from rape. Thomas drew that conclusion explicitly: ‘to my mind, [they were] one of the outstanding reasons why the local Asiatic women were not molested by the invaders’.[79] While there may be some truth is this conclusion, it fails to take into account two factors. Firstly, the Japanese army in other parts of Papua and New Guinea – Buna, Salamaua, Lae, Madang and Wewak – was not guilty of outrageous sexual crimes. While the numbers of Japanese at mainland centres were less than in Rabaul where there were close to 100,000, they were still substantial: 11,000 around Lae and Salamaua in September 1943, and 35,000 in the Sepik in October 1944.[80] In fact, there were probably fewer cases of reported rape and aggressive demands for sex on the mainland than in and near Rabaul. As there were no comfort women on the mainland, they cannot be used to explain the relative restraint of the Japanese. Secondly, the number of rape cases in the Rabaul area may have been understated. The United Straits Strategic Bombing Survey says that at Ratangor where many of Rabaul’s Chinese had taken refuge ‘rape was common in the first year of the occupation’.[81] Peter Cahill, who interviewed Rabaul Chinese about the war, said that his views changed when the respected Chin Hoi Meen told him that ‘Chinese girls had to be supplied to [the Japanese] on demand’.[82] Cahill also quotes the Reverend Mo Pui Sam of the Methodist Mission who stayed in the area: ‘many girls and women were raped. The soldiers of the Japanese First Battalion … raped Chinese women’.[83] Very few Chinese women, Cahill claims, agreed to live with officers and accept their protection, but many were forced into meeting their demands. After the comfort women had left, Chinese men had to draw up a roster of women to be made available each night: the alternatives were threats of beatings, death or incarceration in a soldiers’ brothel.[84] Cahill lists the causes of death of the 86 Chinese who died during the occupation and this includes 37 killed by the Japanese.[85] The Chinese in Rabaul may not have suffered horrific atrocities, but they were victims of violent and sexual assault to an extent that casts doubt on those who have seen the Japanese in New Guinea as disciplined in their relationships with women.[86]

Noriko Sekiguchi has revealed something of those New Guinean women who chose or were pressed into sexual relationships with the Japanese. The documents provide limited information, a point conceded in an intelligence report of 1943 largely concerned with Rabaul:

Stories of rape of native women are rare and generally uncorroborated. Some natives have stated that if a lorry containing Japanese soldiers passes a lone native woman it generally stops and she is picked up, raped as the lorry going along [sic] and put down at some other place. I have heard a number of such stories, but they are nearly all hearsay and may not be founded on fact. At any rate the natives themselves believe them. Raping of native women seems to have been fairly common in the Buna Area, but it was condoned by the men who seemed to accept it as the normal thing in war.[87]

While there has been considerable understatement of the sexual exploitation of Asian and mixed race women by the Japanese, it is probably still fair to say that while particular New Guinean women were raped, the rate of violation was less than the Allies expected, and less than could have been expected from most occupying armies. But there is no obvious relationship between the sexual safety of Asian, mixed race and New Guinean women and the presence of comfort women.

Japanese Zero Airfighter in New Guinea

Those same Japanese servicemen in Rabaul were violent and criminally negligent in their failure to care for prisoners of war and civilians. The killing of 160 surrendered Australians at Tol Plantation is generally known, but the deaths of well over a thousand other American, New Zealand, British, Chinese, Indian and Malay prisoners and conscripted labourers is often overlooked.[88] The killing of groups of New Guineans is rarely recorded, for example, the execution of seventeen New Guineans and one mixed race man at Vunarima in 1944.[89] The association of the violence of battle and rape demonstrated elsewhere by the Japanese forces and other armies was not obvious around Rabaul.

The terms used to refer to the comfort women are numerous and rich in euphemism and implicit judgment. ‘Comfort women’ is itself a euphemism and then there is: consolation unit, geisha girls, kimonoed ladies, lassies, ladies of a thousand delights, slaves, solace women, special necessary personnel, love girls, contract prostitutes.[90] The Australian newspapers in their recent articles have opted for ‘sex slaves’.[91] The contrast in the observer’s perception and the suggestion of the conditions under which the women were recruited and worked between ‘sex slave’ and ‘lady of a thousand delights’ is vast. The vocabulary is indicative of values that change with time, gender and nationality; but it is interesting that ‘slave’ was used by the Australians who saw the women in 1942. [92]

Hank Nelson is emeritus professor in the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies of Australian National University, and author of many studies in Australian and Pacific history, particularly in relation to the Second World War in Australia and the Pacific. This paper was first presented at a Division of Pacific and Asian History seminar at the Australian National University, Canberra on 8 May 2007. It has been submitted for publication to the Journal of Pacific History. Posted at Japan Focus on May 22, 2007.

[1] Age, 13 March 2007. Those issues were again headlines when Abe met President George Bush in Washington in April 2007 (Weekend Australian, 28-9 April 2007).

[2] Nanking rape rewritten’, Australian, 2 March 07, p.12; ‘Tokio and Beijing in historical divide’, Australian, 23 March 07, p.11

[3] Canberra Times, 9 March 07; Weekend Australian, 3-4 March 07. Tessa Morris-Suzuki, ‘Japan’s “Comfort Women”; It’s time for the truth (in the ordinary, everyday sense of the word)’, provides an excellent summary of the current debate and its background. Keiko Tamura also provided information.

[4] Jan Ruff-O’Herne, 50 Years of Silence, Editions Tom Thompson, Sydney, 1994.

[5] Allied Translator and Interpreter Section (ATIS), Interrogation Reports, Vol 1, Chihara Miyaji, Australian War Memorial (AWM) 55.

[6] ATIS, Interrogation Reports, Vol 1, Kazo Arita, AWM 55.

[7] Allied Translator and Interpreter Section, Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers, Amenities in the Japanese Armed Forces, using information available to 31 March 1945, p.19, AWM55, 12/92.

[8] ATIS report on amenities, p.17.

[9] ATIS report on amenities, p.17. ‘Hainin’ indicates of petty officer rank.

[10] ‘Reports from Rabaul – Interrogation of three natives escaped from Buna, 1942’, AWM 54, 608/4/1.

[11] Signed statement of 10 September 1944, ‘Statements made in September 1944 …’, AWM 54, 1010/4/155.

[12] When Australian prisoners of war of the Japanese had to fill in forms giving their occupation, many told their captors that they were brothel testers or beer tasters. The rumour of the brewery advertising for beer tasters is an Australian working man’s fantasy, not then one of New Guineans who were prohibited from drinking alcohol – a condition of the mandate.

[13] Native Conditions in Rabaul, Statement of Chouka of Mouk Island, Manus, 1944, MP1587/1, Item 97I, National Archives of Australia (NAA), Victoria.

[14] Presumably Chouka gave his interview in Pidgin. The term ‘consort’ seems unusual, but Chouka could certainly express the idea in Pidgin. There are also statements from Chouka (Choka) in the Angau War Diary, attached to August 1944, AWM52, 1/10/1. ‘Chauka’ was awarded Loyal Service Medal 194. It is the same man as the citation gives the same history (Appendix HQ A14 to Angau War Diary, August 1944).

[15] H. Nelson, ‘Zentsuji and Totsuka: Australians from Rabaul as prisoners of war in Japan’, in Y. Toyoda and H. Nelson, eds, The Pacific War in Papua New Guinea: Memories and Realities, Rikkyo University Centre for Asian Area Studies, Tokyo, 2006, pp.423-56, and ‘The Return to Rabaul 1945’, Journal of Pacific History, Vol 30, No 2, 1995, pp.131-53 give accounts of the fate of those captured in Rabaul.

[16] D. Hutchinson-Smith, Guests of the Samurai, typescript, copy held by H. Nelson and copy also in AWM, p.9.

[17] Sister ‘Tootie’ McPherson in H. Nelson, Prisoners of War: Australians under Nippon, ABC, Sydney, 1985, p.76.

[18] Hutchinson-Smith, p.35.

[19] Hutchinson-Smith, p.35.

[20] Murphy quoted in H. Nelson 1985, p.158.

[21] Joseph Nason and Robert Holt, Horio You Next Die, Pacific Rim Press, Carlsbad, 1987, p.107.

[22] James McMurria, Trial and Triumph, privately published, 1991, p.13.

[23] Alice Bowman, Not Now Tomorrow: ima nai ashita, Daisy Press, Bangalow, 1996, p.67.

[24] Gordon Thomas, ‘The Story of Rabaul’, Pacific Islands Monthly, March 1946, pp.30-1 and April 1946, pp.32-3, is a summary history of Rabaul and reflects Thomas’s affection for and romantic recall of old Rabaul.

[25] The four civilians were Alfred Creswick (engineer with Coconut Products), James Ellis (electrical and refrigeration contractor), George McKechnie (marine engineer) and Gordon Thomas. Thomas was in Ramale, just inland from Rabaul, when the Australians reoccupied Rabaul.

[26] Gordon Thomas, Rabaul 1942-1945, typescript ms, p.96. H. Nelson has a copy and Pambu has made a microfilm. There are slight differences in the typescripts as a result of minor editing.

[27] Thomas, ms, p.96.

[28] Thomas, ms, p.116.

[29] Thomas, ms, p.116.

[30] Thomas, ms, p.144.

[31] Thomas, ms, pp.117-8.

[32] Thomas ms, p.145.

[33] Thomas, ms, pp.33-4. The priest was probably Father W. Barrow who was a priest in Rabaul. He became ill and was released to join other members of the Catholic Church at Vunapope. As an Irishman, he was from a neutral country. He died later in 1942. Father McCullagh, the only MSC priest to be interned with the civilians in Rabaul and to die on the Montevideo Maru, did not join the civilian internees until after the incident described by Thomas. McCullagh was an Australian.

[34] Thomas ms, p.34.

[35] Thomas, ms, pp.138-9.

[36] Thomas ms, p.34.

[37] Thomas ms, p.35.

[38] Thomas ms, p.35.

[39] Thomas ms, appendix iii.

[40] Thomas ms, p.158.

[41] Thomas ms, p.158A

[42] John Miller jr, United States Army in World War II The War in the Pacific Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul, Department of the Army, Washington, 1959, p.230.

[43] The United States Strategic Bombing Survey (Pacific) The Allied Campaign against Rabaul, Naval Analysis Division, Washington, 1946, pp. 23-5.

[44] Hisashi Noma, The Story of Mitsui and O. S. K. Liners lost during the Pacific War: Japanese Merchants Ships of War, published in English and Japanese, 2002, p.160. One of the New Guineans, Yanganoui, who escaped from Rabaul and was interviewed in 1944, said the comfort women left on a hospital ship that was sunk and all died ( AWM54, 779/9/4, Interrogation of natives evacuated from Pondo and Gazelle Peninsula); but Noma claims that the only Japanese hospital ship sunk was the Buenos Aires Maru. It did leave Rabaul late in 1943 and was carrying women. Noma claims they were 63 nurses (Noma p.150); but Keiko Tamura who has researched the fate of the nurses says that some comfort women were also on board.

[45] Kentaro Igusa, The Jungle and Leaf of Hibiscus: Memoirs of a Navy Surgeon in the South Pacific, privately published, Canada, 1987, p.16. The late David Sissons brought Igusa’s book to my attention.

[46] George Hicks, The Comfort Women, Allen and Unwin, Sydney, 1995, pp.82-3.

[47] Noma Hisashi, p.221. He gives no indication that there were women on board.

[48] Hiromitsu Iwamoto notes some 471 books: ‘Japanese perceptions on the Pacific War in Papua New Guinea: views in publications’, in Yukio Toyoda and Hank Nelson eds, p.50.

[49] The most prolific of those translated is probably the fighter pilot ‘ace’, Sakai Saburo.

[50] Watanabe Tetsuo, The Naval Land Unit that vanished in the Jungle, translated and edited by Hiromitsu Iwamoto, privately published, 1995, pp.8-13. The Japanese version was published in 1982.

[51] Watanabe, p.14.

[52] Watanabe, p.13.

[53] Igusa, p.1.

[54] Igusa, p.17. The Okinawans, although not in the same category of colonised peoples as the Koreans, were outsiders. Wakayama projects south from the Osaka area. When David Sissons wrote his pioneering article on Japanese prostitutes in Australia he found that most of them were from Nagasaki and the nearby peninsula of Kumamoto (‘Karayuki-san: Japanese prostitutes in Australia 1887-1916’, Historical Studies, Vol 17 No 68 pp.323-41 and No 69 pp.474-88. The origins of the women are given in part one).

[55] Igusa, p.18.

[56] Igusa, p.19

[57] Igusa, p.16.

[58] A third doctor has recorded his reminiscences, Captain Aso Tetsuo. Having been in both China and Rabaul and having trained in obstetrics and gynaecology, he had detailed knowledge. His 1939 report on comfort women in China is a basic document. A Christian and an English speaker, he became a friend of one of the Australians, Lieutenant Frank Nicholas, in Rabaul after the Japanese surrender. His diary of being in Rabaul after the surrender has been translated, but not his other writings. AWM PR86/278. Keiko Tamura brought Aso to my attention. His Rabauru nikki (Rabaul diary) was published privately in 1972.

[59]The web site refers to John G. Bishop, Cameras over the Pacific which was probably privately published in 2003.

[60] Hicks, pp.150-1.

[61] I was reading the reports for other reasons, but a reference to finding Japanese or other women should have been sufficiently unusual for me to note it.

[62] See, for example, the trial of General Imamura in which several of the crimes committed by his subordinates were against Indians (Trial of senior Japanese officers, NAA Victoria, MP742/1, 336/1/1205). For investigation of crimes against New Guineans see NAA Victoria, MP742/1, 336/1/1955.and AWM54, 1010/6/65 Reports which were subject of a trial referred to as the Vunarima Massacre Case …

[63] Observers say that they saw women who were ‘almost black’ (Hutchinson-Smith) and these may have been Malay or Indian women, but it is unlikely that they were local Melanesians. Thomas spoke Kunanua, the language of the Tolai people from around Rabaul, and it is likely that he and others would have mentioned seeing any local women in the brothels.

[64] Thomas, ms, p.24; and Strategic Bombing Survey, p.35.

[65] A Report on Taiwanese Comfort Women, The information on the 253 sent to ‘Rabble’ is said to come from a contemporary Japanese source.

[66] Hicks has a concise summary of the emergence of the comfort women into public consciousness, chapter 8, pp.153-78.

[67] A Japanese woman, Shirota Suzuko, had described her experiences on radio, and Yoshida Seiji had written My War Crimes: The Forced Draft of Koreans, San-ichi Shobo, Tokyo, 1983.

[68] Usuki Keiko, Contemporary Comfort Women, Tokuma Shoten, Tokyo, 1992, and Yuki Tanaka, Hidden Horrors: Japanese War Crimes in World War II, Westview Press, Boulder, 1996, chapter 3, ‘Rape and War’, pp.79-109.

[69] Ruff-O’Herne, pp.144-5.

[70] Peter Stone, Hostages to Freedom: The Fall of Rabaul, Oceans Enterprises, Yarram, 1994 (but 1995 on the Foreword).

[71] The headlines show the sequence: ‘Japanese denial on wartime sex slaves’ (Weekend Australia, 3-4 March 2007), ‘Abe orders new sex slave inquiry’ (Canberra Times, 9 March 2007), ‘Abe apologises for sex slaves’ (Canberra Times, 27 March 2007), and ‘Japan tries to defuse row over sex slaves’ (Sydney Morning Herald, 2 April 2007).

[72] Thomas, ms, p.24.

[73] Hicks, p.82, makes the point that the women were ‘brought in “as quickly as the ammunition”’.

[74] Douglas Gillison, Australia in the War of 1939-1945: Royal Australian Air Force 1939-1942, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1962, p.578 notes a heavy raid of August 1942.

[75] Hiromitsu Iwamoto, ‘The Japanese Occupation of Rabaul, 1942-1945’, in Y. Toyoda and H. Nelson, eds, 2006, p.255.

[76] Tanaka, p.95 points out that that there were three types of brothels: those run directly by the army, those with civilian managers but in fact run by the army, and those run by civilians and allowing some civilian customers but having an agreement with the army.

[77] Igusa, p.16.

[78] Anonymous, A Woman in Berlin: Eight Weeks in the Conquered City A Diary, Metropolitan Books, New York, 2005.

[79] Thomas, ms p.35. It is interesting that Thomas with his notion of a strict hierarchy of races did not mention Melanesian women.

[80] David Dexter, Australia in the War of 1939-1945: The New Guinea Offensives, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1961, p.392; Gavin Long, Australia in the War of 1939-1945: The Final Campaigns, Australian War Memorial, Canberra, 1963, p.272. The total of Japanese landed on the New Guinea mainland was over 100,000.

[81] US Bombing Survey, p.35.

[82] P. Cahill, The Chinese in Rabaul 1942-1945, MA qual, thesis, History Department, University of Papua New Guinea, 1970, p.83.

[83] Cahill, p.83

[84] Cahill, pp.84-5. Cahill went back to this material in his MA thesis: The Chinese in Rabaul 1914-1960, History Department, University of Papua New Guinea, 1972, pp.145-7. Cahill concedes that he was reluctant to press for details and that different Chinese gave different accounts. Chinese women also suffered sexual assault by some New Guineans.

[85] Cahill 1972, p.160.

[86] David Y. H. Wu, The Chinese in Papua New Guinea: 1880-1980, Chinese University Press, Hong Kong, 1982, p.77 says that informants told him the Japanese were ‘well disciplined’.

[87] Report on Native Conditions in Rabaul, NAA Victoria, B3476, 24.

[88] As noted earlier, one of the main charges against General Hitoshi Imamura was his responsibility for the ill-treatment and death of the prisoners (NAA Victoria, MP742/1, 336/1/1205, Trial of Senior Japanese officers, and see evidence of Major Waheed, 1st Bn Hyderabad Infantry for a detailed statement of what happened to the Indians).

[89] Reports which were subject of a trial referred to as Vunarima Massacre … AWM54, 1010/6/65.

[90] Keiko Tamura has pointed out that it is the Japanese term ‘ian-fu’ that has been translated as comfort women. ‘Ian’ is still used in terms such as ‘ian ryoko’ (comfort trip) and ‘ian-kai’ (comfort party). Both terms are used within work places. They indicate that a company is accepting responsibility for the pastoral care of employees and are not just providing occasions for indulgence. For the Japanese military, the use of the term ‘ian’ may have implied that the women were made available as part of the military meeting its obligations to look after what were seen as the needs of the men (and to protect them and others from the spread of venereal disease) rather than simply providing for sensual pleasure.

[91] See footnote 66. Aso Tetsuo’s material is obviously important.

[92] A final qualification: nearly all the material used here to build up a picture of what was known about the comfort women and how they worked in Rabaul has been gathered while researching other topics relating to Rabaul. It could be that research directed at comfort women in New Guinea and other parts of the southwest Pacific, and drawing on documents in both English and Japanese, would make a more substantial contribution to the international debates on comfort women and to the broader debates on nations’ acknowledging their own histories.