Introduction by Richard Tanter

While most recently mainstream discussion of peace and security in Asia has focussed on the rise of China and its consequences, a little noticed arms race that has been underway since the end of the Cold War involves many more countries than China. According to Desmond Ball, one of its most constant analysts, this began with widespread modernization of armed forces after the end of the Cold War, but has moved on to continuous systematic increases in military capacity in most countries in the region. Action-reaction patterns of competitive armament cycles are evident, and most disturbingly, there are few bilateral or regional political institutions to dampen these negative feedback cycles. For Ball, the most important areas where this kind of action-action momentum can be seen, are major naval capabilities; long-range ballistic and cruise missiles, and missile defence systems; electronic warfare systems; and information warfare (IW) and cyber-warfare capabilities.1

Those naval capabilities include submarines, and their counterpart, the electronic technologies of anti-submarine warfare. Submarine builders are busy in Asia at the moment. India is building six new nuclear attack submarines, and China is selling Pakistan eight diesel/electric submarines. South Korea has established a consolidated submarine command to manage its Harpoon-equipped missile diesel-electric fleet of nine German-designed Type 209 submarines, and will have five more by 2019. Russian builders handed over a Yasen-class nuclear attack sub and a Borey-class SSBN last year, and four more nuclear boats have been laid down in Archangelsk’s shipyards, some of which will go into the modernization of the Pacific fleet. And China’s nuclear attack submarines now pass through the Malacca Straits to Indian Ocean patrols. India, meanwhile, in addition to its expanding nuclear fleet, has approached Japan to buy six of its big, 4,600 tonne Soryu-class diesel-electric submarines with its air independent propulsion system.2 In the largest of the non-nuclear plans in the region, albeit with a policy process not notable for either strategic rationality or transparency, Australia is making final decisions on buying or building 12 large submarines – most likely Japanese Soryu-class submarines, or smaller European submarines.3

Consequently, anti-submarine warfare planners are busier still, particularly those in China, and in America’s East and Southeast Asian allied countries. Like Soviet submarines before them, Chinese submarines attempting to reach the protection of the deep waters of the mid-Pacific must run the gauntlet of the American-dominated choke points between the island chains that reach from the Kurils through Japan and the Ryukyus and the Philippines and Indonesia. In a complex set of regional maritime environments for the perennial contest between submarines and their surface, air and undersea hunters, the current clear US and allied naval dominance, including in anti-submarine warfare, will be increasingly tested in coming decades, with consequent implications for long-term submarine-building plans.4

The critical wider context for these armaments dynamics is of course the complex relationship between the United States and China, and the fateful question of its future possible directions, in the short term, and especially in the longer term. Despite American power transition narratives of inevitable military conflict between established and revisionist powers, there are choices to be made, with alternative possible futures. But at present, one of the most dismaying aspects of much US v. China thinking in Washington and its regional allied capitals is talk, often in a blasé or insouciant way, of the near-term possibility of war between the US and China, with a matching chorus in China itself.

The veteran Australian journalist Hamish Macdonald here examines the strategic consequences of one aspect of these naval arms races in Japan’s development, together with the United States, of a remarkably extensive and powerful system of underwater electronic surveillance capacities based on Desmond Ball’s and my study The Tools of Owatatsumi: Japan’s Ocean Surveillance and Defence. Together with Robert Ayson, Ball subsequently closely examined the question ‘Can a Sino-Japanese war be controlled?’, reviewing the widespread, indeed barely questioned, assumption that such a conflict, for example over the East China Sea territorial disputes, can be contained to a ‘limited war’.5

Examining in detail both technical and political aspects of such a confrontation, including the vulnerability to attack of Japan’s potent undersea surveillance capacities that we documented, Ball and Ayson concluded that in the relationship between Japan and China:

there seems to be minimal political understanding of, or commitment to, avoiding escalation…These political obstacles increase the pressure created by military considerations that encourage swift escalation, to the point at which even nuclear options seem attractive…The subsequent involvement of the United States could lead to Asia’s first serious war involving nuclear-armed states. And we have no precedent to suggest how dangerous that would become.

While it looks like China has the US and Japan on the defensive in pushing its maritime claims and expanding its maritime power, a closer look suggests the two powers have the Chinese cornered.

It’s about “humanitarian civil aid”, Australia’s Defence Department would have us believe about Exercise Balikatan which began in and around the Philippines on April 20. And indeed about 70 army engineers were duly sent to work on projects in Filipino villages on Luzon and Palawan when Australia joined the militaries of the United States and the Philippines for 10 days of exercises.

Practising for “natural disasters” has become something of a cover story, it seems, for what is going on in the tightening network of American alliances in the Western Pacific since Barack Obama announced the annual rotation of a US Marine Corps task force through Darwin in November 2011 as a part of a strategic “pivot” or “rebalancing” to Asia.

But if it were just about cleaning up after cyclones, it is unlikely Canberra would be sending along one of the Royal Australian Air Force’s AP-3C Orions to Exercise Balikatan as well as the engineers. Bristling with electronic, infra-red and magnetic sensors, acoustic buoys to drop, and on-board computing power, the aircraft is one of the world’s most advanced aerial platforms for detecting hostile ships and submarines and vacuuming up local communications.

In fact, the sea and air elements of Balikatan play out close to where Chinese dredgers have been frantically pumping sand onto coral reefs in the Spratley Islands, also claimed by the Philippines and other Southeast Asian states. The Filipinos themselves say the exercise will “increase our capability to defend our country from external aggression”.

The exercise comes just after the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington institution close to the thinking in the Pentagon, published before and after satellite pictures of the Chinese reclamation work in the Spratly Islands, and the visiting chief of the US Navy’s Pacific fleet, Admiral Harry Harris, told a Canberra audience about the “Great Wall of Sand” China was building in the disputed islands far out from its coast, studded with ports and airstrips to intensify control over the South China Sea.

Meanwhile Chinese ships and aircraft continue regular incursions around the Japanese-controlled Senkaku islands to the north of Taiwan, to assert claims of historical ownership. As recently as last year, Chinese fighter jets have jostled American patrol planes in the area.

With all this Chinese aggression, or “assertiveness” as it’s often more diplomatically put, you might be forgiven for thinking that the naval and air wings of the People’s Liberation Army have the Americans and Japanese on the back foot, unwilling to risk a clash that the Chinese seem all too ready to escalate.

But a new study by two Australian experts suggests it is the Chinese who are cornered. Desmond Ball, the Australian National University nuclear strategist and analyst of electronic spy craft, and Richard Tanter, an expert on Northeast Asian security and nuclear issues at Melbourne University and the Nautilus Institute, suggest Japan and the US have China’s forces surrounded by trip wires.

Their book The Tools of Owatatsumi (the name refers to the sea god protecting Japan in ancient legend), details the networks of undersea hydrophones and magnetic anomaly detectors which, combined with data collected by ground stations, patrol aircraft and low-orbit satellites, make it virtually impossible for Chinese ships and submarines to break out into the wider ocean undetected.

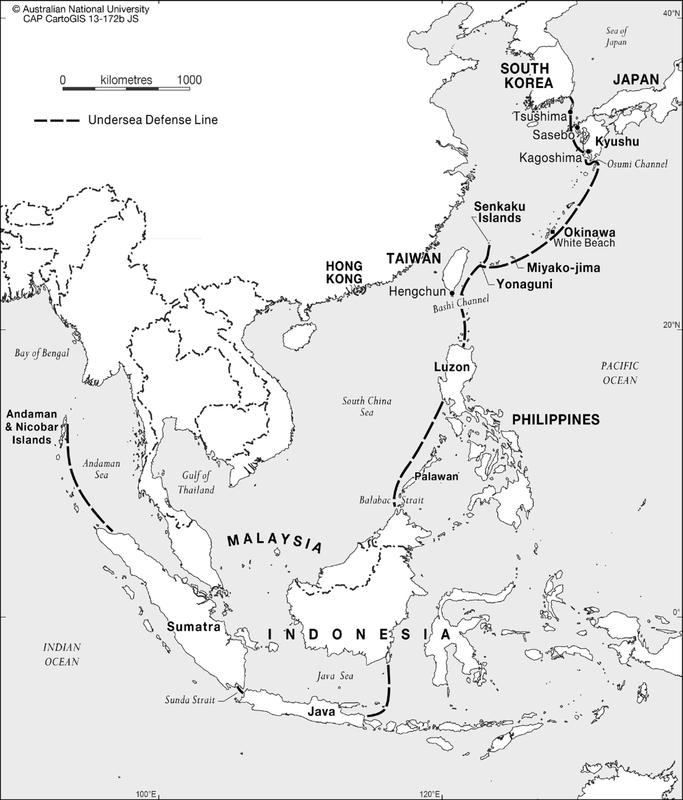

The tripwire around the Chinese navy extends across the Tsushima Strait between Japan and Korea, and from Japan’s southern main island of Kyushu down past Taiwan to the Philippines. When first revealed, in a little-noticed article by Taiwan military intelligence official Liao Wen-chung in 2005, it was described as a “Fish Hook Undersea Defence Line”.

Controversially, the curve of the hook stretches across the Java Sea from Kalimantan to Java, across the Sunda Strait between Java and Sumatra, and from the northern tip of Sumatra along the eastern side of India’s Andaman and Nicobar island chain. Unlike the northern stretches around Japan and Taiwan where the network involves close Japanese and American collaboration, these extensions into Southeast Asia would be largely American installed and operated.

Indonesia and India, both historic adherents of non-alignment despite recent warming to the US in the face of rising Chinese power, would be loath to admit allowing the Americans to wire up their nearby waters, and would be perhaps even more embarrassed to learn that it had been done without their permission or knowledge.

Ball himself is not sure whether these Southeast Asian sections of the line consist of fixed acoustic surveillance arrays in the manner of the long northern sections from Tsushima down past the Philippines. “I would expect the more southern segments to have been fully surveyed and prepared for expeditious deployment of other elements of the integrated undersea surveillance system in contingent circumstances,” he says.

These include towed-arrays trailing behind surface ships and small acoustic sensors that can be scattered across the seabed unobtrusively at short notice in a program called the Advanced Deployable System.

“Outward movement of the Chinese subsbasedat Hainan would be very closely monitored, whether they headed south or north,” Ball said.

Information sharing between the US and Japan joins the undersea defence line up, effectively drawing a tight arc around Southeast Asia, from the Bay of Bengal to Japan. China can’t move in or out of this net without being spotted by the potential hunters.

It is with all this in mind that one might reconsider the purpose of the US-led Exercise Balikatan in the Philippines –and the presence of weapons platforms like the RAAF’s AP-3C Orion. It is for fishing inside the net.

The undersea system has not gone unnoticed by the Chinese. Their surveillance ships have sailed close to the Japanese shore stations where data from the arrays is processed. In 2006, Japan arrested for espionage a naval petty officer at its Tsushima Island anti-submarine base: he had made eight trips to Shanghai and been compromised by a relationship with a hostess from a karaoke bar. Swarms of Chinese fishing boats, sometimes called a “maritime militia”, have jostled American semi-civilian survey ships like the Impeccable that sail close to Chinese submarine bases in Hainan and elsewhere towing long sonar arrays to map local waters and record acoustic signatures of Chinese vessels.

In July 2013, Chinese newspapers reported that Japan and the US had built “very large underwater monitoring systems” north and south of Taiwan, and that large numbers of hydrophones had been installed “in Chinese waters” close to Chinese submarine bases.

More recently China has raised the alarm at the commissioning of Japan’s largest post-1945 warship, the helicopter-carrier Izumo, which could be modified to carry the jump-jet version of the F-35 strike fighter, and at the Abe government’s floating of the idea of extending Japan’s air and sea patrols into the South China Sea.

“The underwater approaches to Japan are now guarded by the most advanced submarine detection system in the world,” Ball and Tanter write. In addition, the “Fish Hook” ensures that Chinese submarines are unable to move undetected from either the East China Sea or the South China Sea into the Pacific Ocean. “It suggests that even without recourse to the overwhelming US assets, Japan would be ascendant in any postulated submarine engagement with China,” they said.

While this leaves the Chinese able to reinforce their positions in the South China Sea against the weaker regional claimants to territory – Vietnam, Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei, the Philippines and Taiwan as the alternative China – it might suggest a comfortable level of conventional deterrence held by Japan and reduce the prospect of war between East Asia’s two biggest powers and in Australia’s case, its two biggest trading partners.

However, it raises two uncomfortable conclusions. One is that the US and Japan now have more reason than ever to discourage Taiwan from re-unifying with the Chinese mainland, because it would irreparably break the tripwire. Taiwan’s presidential election next January could see the Chinese nationalist party (Kuomintang, or KMT) lose power to an opposition DPP that has previously flirted with declaring independence and would at the very least back peddle on the KMT’s efforts to integrate Taiwan’s economy with that of the mainland. This would be another blow to China’s recent soft line of economic and people-to-people ties, encouraging Communist Party and PLA hardliners to think of sudden strikes.

The other, raised by Ball and Tanter, is the risk of uncontrolled escalation of clashes at sea or in the air. Japan’s superiority relies on these electronic surveillance facilities. While China might try jamming them, their isolated locations might tempt China into commando operations or strikes with guided weapons.

This vulnerability brings pressures to escalate any clash – on Japan to take out Chinese naval forces before the ability to track them is lost, on China to take out the shore stations first. Some facilities, such as the Japanese naval data processing centre at White Beach, Okinawa, “might be regarded as sufficiently important to warrant pre-emptive nuclear attack,” they write.

The US could not avoid entanglement, Ball and Tanter say. Aside from its treaty obligations to Japan, its own surveillance systems are co-located with Japan’s and the northern sections of the “Fish Hook” are as vital to US interests as those of Japan.

“The US Navy could not abide its degradation,” Ball and Tanter said. “At a minimum it would be compelled to attempt to destroy any Chinese missile-carrying submarines while aware of their locations, before they are able to pass through a broken ‘Fish Hook’ line and come within firing range of the continental United States.”

This is the standoff that Australia’s defence forces are eagerly equipping themselves to join. Current procurements include a doubling of the submarine fleet to 12, with a new generation of large conventional submarines. The Australian Prime Minister, Tony Abbott, has made little secret of his wish for those submarines to be derivatives of Japan’s new Soryu-class boats. In addition there are three Aegis-radar equipped air warfare destroyers that the US Navy would like to integrate into theatre missile defence cover. Two new amphibious ships each capable of transporting a battalion of troops for landing by helicopter and boat seem vastly in excess of smaller capabilities required for interventions in likely trouble spots in the South Pacific. The air force is gaining F-35s, Poseidon patrol aircraft, and drones.

The Australian forces are becoming a model for the kind of “interoperability” being pushed on allies and friendly nations around Asia, which veteran diplomats like John McCarthy, a former Australian ambassador to Washington, Tokyo, Jakarta and New Delhi, fret could lead to “automatic” involvement in conflicts that don’t directly affect Australian interests.

Hamish Macdonald is a former foreign editor of The Sydney Morning Herald and regional editor of the Far Eastern Economic Review. He is now world editor of the Australian weekly The Saturday Paper where the original version of this article appeared.

Richard Tanter is Senior Research Associate at the Nautilus Institute and teaches in the School of Politics and Social Science at the University of Melbourne. He is a Japan Focus contributing editor.

Recommended citation: Hamish McDonald with an introduction by Richard Tanter, “The Wired Seas of Asia: China, Japan, the US and Australia”, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 16, No. 2, April 20, 2015.

Related articles

•Vince Scappatura, The US ‘Pivot to Asia’, the China Spectre and the Australian-American Alliance

•Richard Tanter, The US Military Presence in Australia: Asymmetrical Alliance Cooperation and its Alternatives

•Richard Tanter, An Australian Role in Reducing the Prospects of China-Japan War over the Senkakus/Diaoyutai?

Notes

1 Desmond Ball, “Asia’s Naval Arms Race: Myth or Reality? 25th Asia-Pacific Roundtable”, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 29 May – 1 June 2011.

2 Jeremy Page, “China’s Submarines Add Nuclear-Strike Capability, Altering Strategic Balance”, Deep Threat, Wall Street Journal, 24 October 2014; David Tweed, “Xi’s submarine sale raises Indian Ocean nuclear clash”, Bloomberg, 17 April 2015; Trude Pettersen, “Four nuclear submarines under construction in Russia’s Far North”, Barents Observer, Alaska Dispatch News, 18 February 2015; Zachary Keck, “China’s Worst Nightmare? Japan May Sell India Six Stealth Submarines”, The Buzz, The National Interest, 29 January 2015; Akhilesh Pillalamarri, “Watch out, China: India is building 6 nuclear attack submarines”, The Buzz, The National Interest, 18 February 2015; Zachary Keck, “Silent but Deadly: Korea’s Scary Submarine Arms Race”, The Buzz, The National Interest, 13 February 2015; and Yoo Kyong Chang and Erik Slavin , “South Korea Establishes Submarine Command”, Stars and Stripes, 23 February 2015.

3 Richard Tanter, “The $40 billion submarine pathway to Australian strategic confusion”, Nautilus Institute, NAPSNet Policy Forum, 20 April 2015.

4 Owen R. Cote Jr., “Assessing the undersea balance between the U.S. and China”, MIT Security Studies Program, SSP Working Papers, February, 2011; Paul Dibb, “Maneuvers make waves but in truth Chinese navy is a paper tiger”, The Australian, 7 March 2014; and Desmond Ball and Richard Tanter, The Tools of Owatatsumi: Japan’s Ocean Surveillance and Defence, ANU Press, 2015.

5 Desmond Ball and Richard Tanter, The Tools of Owatatsumi: Japan’s Ocean Surveillance and Defence, ANU Press, 2015; and Robert Ayson and Desmond Ball, “Can a Sino-Japanese War Be Controlled?”, Survival: Global Politics and Strategy, (2014) Vol. 56, No. 6, pp. 135-166.