Weapons of Mass Destruction, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the Atomic Testing Museum

by Greg Mitchell

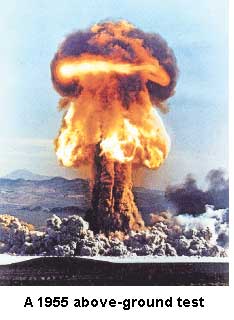

[For forty years, beginning with a desert test visible from the Sky Bar at Las Vegas’ Desert Inn, 928 nuclear devices were exploded at the Nevada test site, many of them above ground. In March 2005, the 8,000 square foot Atomic Testing Museum opened its doors near the Las Vegas strip. As Greg Mitchell records in the following piece, the museum is as notable for what goes unmentioned as for the events it depicts: these include the victims of the first atomic bombs dropped at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the plight of the “downwinders”, more than 12,000 of whom have filed claims in relationship to cancer and other illnesses that may be linked to the nuclear tests or uranium mining.]

Part I

April 23 — Judith Miller has a WMD problem. She sees them where they don’t exist. Where they did exist she tells only half the story.

Her prominent articles for The New York Times in 2002 and 2003 about alleged weapons of mass destruction in Iraq helped pave the way for a war that has killed or damaged thousands of soldiers and innocent civilians. Yet in a little-noticed essay last week in the same newspaper she downplayed the effects of WMD detonated in the United States that killed or damaged thousands of soldiers and innocent civilians.

This well-crafted Miller tale appeared last Wednesday in a special New York Times supplement on Museums. Buried on page 15, it no doubt attracted far fewer readers than her front-page stories offering proof of Iraq’s nuclear and chemical weapons. It described Miller’s recent visit to Las Vegas for a tour of the Atomic Testing Museum, a $3.5 million facility affiliated with both the Department of Energy and the Smithsonian Institution, which opened on February 20.

As a youth in Las Vegas, Miller, it turns out, lived through dozens of nuclear eruptions at the Nevada Test Site, about 65 miles away. In the story she recalls those days of “pride and subliminal terror,” though she doesn’t offer any personal details beyond a wild rumor about a dog melting after the Dirty Harry blast in 1953. She also recalls exchanging cereal box tops for an atomic ring, but this was not unusual: Almost 3,000 miles away in Niagara Falls, N.Y., I sent away for the same prize.

Miller asserts that there “probably never was a dead dog,” but fails to mention that the same 1953 test killed thousands of sheep and other animals. This is typical of her story.

In the article, Miller describes some of the pop culture artifacts at the museum, including a cutout display of Miss Atomic Bomb whose nude body is partly covered by a mushroom cloud. The gift shop sells an Albert Einstein “action figure.” But she does not review the Vegas theme park feature: the Ground Zero Theater, which simulates a nuclear blast, complete with countdown, explosions, vibrating benches, and a whoosh of air into the room to approximate a shock wave.

In passing, Miller discloses that Hank Greenspun, the rabidly pro-nuclear owner of the Las Vegas Morning Sun — he called health concerns surrounding the blasts “frivolous” — was a friend of her father’s. Two of the reasons Greenspun and others in Vegas defended the testing: 1) it brought tourists to town to witness the fireballs in the distance, and 2) if the blasts were seen as dangerous it might halt the local business boom in its tracks.

What Miller doesn’t reveal is that her father was one of those businessmen with a stake in keeping health hazards hush-hush. Bill Miller, former owner of the Riviera nightclub in Fort Lee, N.J., which hosted shows by Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin, had moved to Vegas in 1953. He bought a 10% interest in the Sahara Hotel and took over as entertainment director. Besides booking the big room, he is credited with inventing the “lounge act” as a highly profitable niche. Later he worked at the Flamingo and the International Hotel, where he booked one of Elvis Presley’s famed 1969 shows. A survey of the top 100 people “who shaped Southern Nevada” by the Las Vegas Review-Journal dubbed Miller, who died in 2002, “Mr. Entertainment.”

The casual reader of Miller’s article, nevertheless, might consider it fairly balanced, since it does (briefly) mention that fallout from the bomb tests likely caused harm to “some” of the 200,000 soldiers forced to witness them at close range. But Miller fails to note that the GIs were often used as “guinea pigs,” ordered to march right under the mushroom cloud, without protective clothing, to test the effects.

She admits that citizens who lived downwind from the blasts, principally in Utah, may have suffered, but quickly adds that the true effects “may never be known, given the paucity of epidemiological studies.” This is playing coy. A study issued at the request of Congress by the Centers for Disease Control and the National Cancer Institute in 2003, for example, estimated that fallout produced by the atomic tests and carried near and far might have led to approximately 11,000 excess deaths, most caused by thyroid cancer linked to exposure to iodine-131.

Miller recognizes that Americans have different views of the testing era — one side arguing that it saved the country from certain attack by the Soviet Union, the other pointing out the longterm damage caused by nuclear waste, nuclear proliferation, and the culture of secrecy (which all remain threats today) — but she suggests that the museum itself does not choose sides. But here’s what museum director Bill Johnson has said in widely published accounts: “This museum’s position is that the Nevada Test Site was a battleground of the Cold War and it helped to end it.”

The final artifact in his museum: a chunk of the Berlin Wall. It could have just as easily been a video of an angry leader of Iran or North Korea threatening us with the bomb today. Miller’s own paper today carries a lengthy report on U.S. plans to modernize an old nuke or build new ones.

As it happens, I know a bit about this subject. Besides living through the scary 1950s myself, I’ve co-authored a book and written dozens of articles (two for Miller’s newspaper) on the general subject, and I edited a magazine for several years called Nuclear Times. One thing that jumped out at me in Miller’s story was her failure to even mention Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the loss of more than 200,000 lives there following America’s first atomic test, though she was all too willing to raise the image of nuclear annihilation in some of her bogus WMD articles for the Times.

So I decided to take a closer look at the museum, its contents, and what, if any, criticism of it has emerged.

Not surprisingly, I learned that the “downwinders” had protested the official opening, calling the museum displays nothing less than “propaganda.” And it didn’t take long to find one major article that took a quite different tone than Miller’s. Written by Edward Rothstein after his visit to the museum, it was published in Miller’s own paper on Feb. 23. It reminded me that during Miller’s days on the Iraq WMD beat other Times reporters often contradicted her reporting, if to little avail.

Rothstein observed that “the history of testing, as told here, is largely the history of justification. Problems and issues are noted, including the debates about the effects of fallout that grew more intense as the testing proceeded. But such issues are mentioned and then put aside, to get on with the main story.”

Calling this a “crucial flaw,” he continued: “The entire museum would be stronger if it made those risks more palpable, and more directly addressed the fear knitted into the awe: the reasons, for example, epidemiological studies have asserted that childhood leukemia rose in areas affected by fallout; or the ways the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) of the early 1950’s has been accused of misjudging the effects of radiation and failing to inform the public fully. … The museum, despite its accomplishments, leaves many unanswered questions about the past.”

In fact, Miller fails to emphasize the outright boosterism of the museum, and its failure to call the official assurances to downwinders in the 1950s by their proper name: lies. Now that internal reports have been declassified, we know that the AEC chose to ignore warnings from its own scientists and outside researchers and continued the “nothing-must-stop-the-tests” policy, applauded by Las Vegas casino and hotel owners.

And that 1953 test that probably did not kill a dog but did off 4,390 sheep and lambs? A now-declassified AEC report reveals that “fallout from the burst covered most of the country east of the Rockies.”

From all I’ve read — and from my lengthy email exchange with museum director Johnson — it seems the latest Vegas tourist attraction pays homage to, perhaps even glorifies, the testing program, and by extension, the entire nuclear arms race.

In his dedication speech, Linton F. Brooks, chief at the National Nuclear Security Administration — who, incidentally, is pushing for those new, improved, nuclear weapons — said the museum “helps us celebrate victory in America’s longest war.” He meant the Cold War. Actually, American’s longest war is its fight to survive the worldwide nuclear menace, and it continues.

Part II

The Undead

The new Atomic Testing Museum in Las Vegas not only downplays the health and safety fallout from the nuclear era here at home. It also offers a misleading historical narrative on the only use of nuclear weapons against a foreign power, and it fails to mention that anyone died from that use.

In my previous column, I looked at New York Times reporter Judith Miller’s favorable account of her visit to the museum, affiliated with the Department of Energy and the Smithsonian, which opened Feb. 20. As I observed, another reporter at Miller’s paper, Edward Rothstein, after his own tour, struck a quite different note, citing a “crucial flaw” at the museum: its tone of “justification” and its leaving “many unanswered questions about the past.”

In her story, Miller also failed to make any mention of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, or the museum’s treatment of the atomic attacks — this from a reporter who helped pave the way for the war on Iraq by raising the specter of nuclear annihilation. But she’s not alone: I haven’t seen anything about the atomic attacks in any other press coverage of the museum.

It set me to wondering how the museum tackled the only use of The Bomb against an enemy (in contrast to the hundreds of times we used it on ourselves), so I emailed a set of questions to museum director William Johnson.

This is not just one of my (many) idle concerns. I have probed the use of the bomb against Japan, and its aftermath, for more than 20 years, after spending several weeks in Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1985 when I was editor of Nuclear Times magazine.

It’s an endlessly fascinating subject because even after nearly 60 years honorable people honorably disagree about whether the U.S. absolutely needed to use the bomb against Japan, at that time, in that way.

According to the lengthy e-mail reply from director Johnson, the museum does not merely cover the hundreds of Nevada tests starting in the early 1950s, but goes back to the beginning of the nuclear era with the first detonation at the Trinity site in New Mexico in July 1945. It then moves forward, briefly, to the atomic attacks less than a month later on Hiroshima (August 6) and Nagasaki (August 9).

From the exhibits, however, you’d never know for certain that anyone died in the attacks. In an email to me, director Johnson said: “The numbers are not explicitly stated.”

The museum does show a mushroom cloud and single images of the ruins of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, but here (as provided by Johnson) is the text of the main panel in the museum on this subject:”In an effort to end the war with Japan quickly and with the fewest casualties, an untested uranium bomb, named Little Boy, was detonated over Hiroshima, Japan, on August 6, 1945. When Japan did not surrender, a second bomb of the same design as the Trinity device, named Fat Man, was detonated over Nagasaki, Japan, on August 9, 1945, with devastating results. Japan surrendered five days later.”

The next panel, titled “Ending World War II,” goes back in time a bit for this narrative:

“A belief that an Allied invasion of the Japanese mainland would be very bloody with estimates of American casualties alone running up to one million abounded. Policy makers unanimously concluded the atomic bomb would end the war with the least bloodshed and should be used without warning against military targets. Accordingly, two atomic bombs were detonated over industrial military targets in early August 1945. Japan surrendered shortly afterwards ending World War II, avoiding a massive Allied invasion and post-war division among the victors.”

This echoes the result of the uproar surrounding the display of the Enola Gay, the plane that carried the Hiroshima bomb, at the Air & Space Museum in Washington, D.C., back in 1995, and later when it went on permanent display last year in Virginia. After protests, mainly from veterans groups and their congressional allies, no mention of Japanese casualties — or the historical debate surrounding the use of the bomb — was permitted.

One might call that the immaculate deception.

Space does not permit a full discussion here of the decision to drop the bomb. But, in brief, what’s wrong with the A-bomb narrative at the museum is the historical inaccuracies serving that “justification” tone cited by reporter Rothstein.

For example, the old chestnut that an American invasion of a clearly defeated Japan (assuming it did not surrender) would have cost a million lives has been discredited by leading historians for two decades now.

Then there’s the museum labeling the two cities “military” targets or, fudging, “military industrial” targets. Neither city was targeted because of its military significance: they were simply among the few cities left in Japan that had not already been devastated by U.S. bombs and so could serve as ideal test sites for the new weapon.

In fact, the aiming points for the bombs were not military bases but the very center of each city, to maximize civilian casualties. In Nagasaki there were only scattered Japanese military casualties (along with a few American POWs), and the civilian toll in Hiroshima outnumbered military deaths by about 6-1, as planned.

Finally, the museum’s narrative ties the end of the war strictly to the use of the bombs, without mentioning the utter hopelessness of the enemy’s cause, Russia’s declaration of war on Japan (as pre-arranged), and the United States’ suddenly changing policy to allow the Japanese to keep their emperor all prior to the surrender.

Actually, there’s an amazing admission in the museum’s text: a rare mention (in the official Hiroshima narrative) that a major factor in driving the use of the bomb was to avoid the “post-war division among the victors.” This oddly echoes critics of the bombing who call it not so much the last shot of World War II as the first shot of the Cold War.

This is a wholly inadequate discussion of these issues, of course, but that will have to do for now.

Given the fact that a majority of Americans, past and present, have always backed the atomic bombings — many World War II veterans, understandably, feel they owe their lives to it — my writing in this field has always focused on trying to inspire readers and reporters to revisit the historical record, to put aside emotion and conventional wisdom (as sadly reflected by the Atomic Testing Museum), take a second look at this question, weigh the evidence, and make up their own minds.

Many might be surprised, at least, to learn that Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, years later, declared that there was no need to attack Japan with “that awful thing,” and that Admiral William Leahy, President Truman’s wartime chief of staff, who chaired the Joint Chiefs, said “the use of this barbarous weapon at Hiroshima and Nagasaki was of no material assistance in our war against Japan. The Japanese were already defeated and ready to surrender … in being the first to use it, we adopted an ethical standard common to the barbarians of the Dark Ages.”

Why does this matter today? How we, as a nation, regard the first atomic bombings may dictate what happens when another urgent international crisis demanding a tough response arises. It’s often said that there is a taboo against using the bomb, but Americans have already made two exceptions, so why not more?

Greg Mitchell is the editor of Editor & Publisher and the author (with Robert Jay Lifton) of Hiroshima in America: A Half Century of Denial (Putnam, 1995), and other books. He was editor of Nuclear Times magazine from 1982 to 1986, and chief consultant to the award-winning documentary “Original Child Bomb” (2004).

These articles, slightly abridged here, were published in Editor & Publisher on April 3 and April 7, 2005. Posted at Japan Focus on April 27, 2005.