The Rails Are Geopolitics: Linking North and South Korea and Beyond

Yonhap News and Georgy Bulychev

[The resumption of the railroad link between North and South Korea is emblematic of warming North-South relations and a key to the geopolitics and geoeconomics of Northeast Asia and beyond. This is a two part article on the the significance of the North-South railroad line crossing Korea’s DMZ and linking Korea with China, Russia and Europe. The South Korean Yonhap New Agency details the last-minute cancellation of the test run scheduled for May 25, 2006. Russian analyst Georgy Bulychev examines the geopolitics of the project and its importance for North-South and regional accommodation and cooperation.]

North Korea Cancels Test Run of North-South Railroad

Seoul, May 24 (Yonhap News) — North Korea on May 24 called off scheduled test runs of cross-border railways, an official at the Unification Ministry said.

The cancellation came one day before the Koreas were set to test the railways.

The South Korean government expressed deep regrets in a statement read by Vice Unification Minister Shin Un-sang during a press briefing.Shin said the North’s chief delegate to inter-Korean talks about linking the railways sent a telegram early Wednesday, saying it is calling off the test runs on the eastern and western lines.

“The North Korean side said in a telegram that it is no longer able to conduct the railway tests as scheduled because of the lack of a military agreement to guarantee the safety (of people taking part) in the trial runs and unstable conditions in the South,” Shin told the news briefing.

A train at Imjingak Station near the DMZ

The North’s delegation to the railway talks is headed by Park Jong-song, director of an external relations bureau at the country’s Railway Ministry, according to the Unification Ministry.

In the statement, the Seoul government criticized the last-minute cancellation, labeling the North’s cited reasons as absurd, or preposterous. “Speaking preposterously about unstable conditions in the South is especially unreasonable.”

Vice Minister Shin claimed it was a temporary delay until the countries’ militaries reach an agreement on the safety of people taking part in trial runs on the railway lines.

Seoul has unsuccessfully tried to win direct approval from the North’s military for the trial runs.

A North Korean delegation to the latest round of inter-Korean military talks on the South Korean side of the demilitarized zone last week returned home without signing a sought-after agreement on measures to guarantee the safety of passengers using the cross-border train services when they resume. The North Korean delegates had also refused to sign an agreement on the safety of people taking part in the historic test runs.

Still, the last-minute cancellation caught Seoul off guard as its agreement with Pyongyang to test the lines was believed to include consent, if not approval, from the communist state’s military.

“In the Tuesday telegram, North Korea called for discussions on redrawing the sea border in the West Sea in response to our telegram asking for any form of agreement regarding the railway operation,” a Defense Ministry source said, asking to remain anonymous.

North Korea’s military insists that a new sea border should be drawn further south away from its coast if there is any progress in talks involving both military authorities. But South Korea wants to discuss the sea border issue at a new round of inter-Korean defense chiefs’ talks.

The western sea border was not clearly marked when the 1950-53 Korean War ended. The U.S.-led U.N. Command delineated a de facto border, the Northern Limit Line, in the area, but the North has never recognized it.

In 1999 and again in 2002, the navies of the two Koreas fought bloody gun battles in the area that resulted in heavy casualties on both sides. Both clashes occurred in June, the peak of the blue crab season, which usually starts in March.

The Koreas agreed to conduct test-runs on both railways, one connecting Seoul to the North Korean capital Pyongyang and the other linking the countries’ eastern provinces of Gangwon, at the end of two-day talks on May 13.

A South Korean ministry official, speaking on the condition of anonymity, had previously claimed the May 13 agreement showed that the North’s military was finally giving in to the economic needs of its impoverished state. “What is important is that the North’s military seems to have no choice but to follow (the government’s position) in the process, although it is still showing a lukewarm attitude,” the official said Tuesday.

The communist state has depended on international aid, mainly from the South, to feed a large number of its 23 million population since the mid-1990s.

The Seoul-Pyongyang line was reconnected late last year for the first time in over 55 years, after it was severed during the 1950-53 Korean War. Construction for the new eastern line was also completed before the end of last year.

Seoul had expected that the scheduled tests of the railways would take place without any disruptions as it believed the May 13 agreement with Pyongyang could override any opposition from the communist state’s military. According to the Korean Armistice Treaty, any entry or exit to and from the reclusive North must receive prior approval from the North’s military.

The Koreas remain divided along a heavily-fortified border since the end of the Korean War, with more than 1.8 million troops from both sides still confronting each other.

This article appeared in Hankyoreh, the independent South Korean newspaper on May 24, 2006.

The Geopolitics of the North Korea-South Korea Rail Link to China, Russia and Europe

By Georgy Bulychev

Cancellation of the 25 May 2006 test run of a train scheduled to cross the DMZ between South and North Korea illustrates the exquisite delicacy of geopolitical issues that continue to defy South-North accommodation. If and when a test run proceeds, it will hold enormous significance for both sides. For once the train starts to run, its momentum will be difficult to stop.

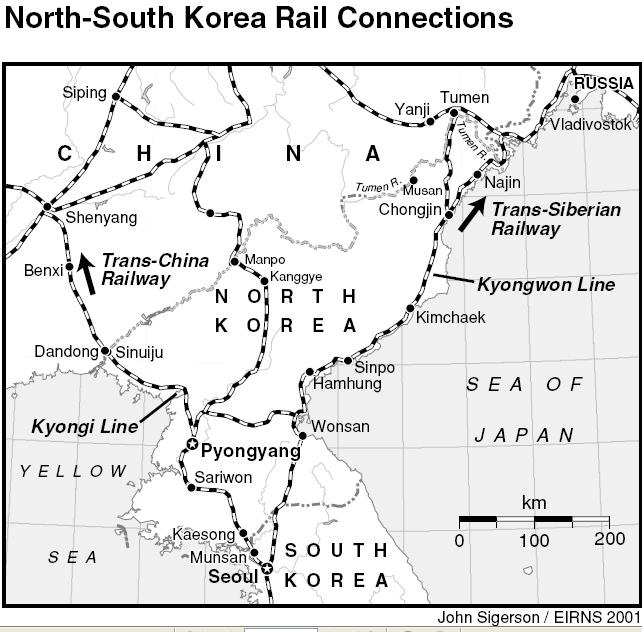

Southerners pay most attention to the Western line (Kyonguison), which would run from the DMZ north all the way along the West coast of North Korea to Sinuiju- and further to China. It would also help connect the two capitals, Seoul and Pyongyang. Northerners, for their part, concentrate on the Eastern route (Donghaeson) linking South Korean railroads – probably from Pusan – directly to the Trans Siberian Railroad and Europe beyond.

Irrespective of route, the opening of train communications will have important implications for regional geopolitics as well as (and perhaps even more than) North-South relations. From the broad geo-political perspective, even if former South Korean president Kim Dae Jung eventually takes the train on his projected June 2006 visit to Pyongyang (as he has indicated he hopes to do), the significance of real progress on the cargo transit from Korea to Europe (Trans-Korean-Trans Siberian TKR-TSR project) is much higher.

North and South Korea Rail Lines

The very natural idea of a land connection between South Korea and Eurasia from the start was highly politicized and it has become only a small part of a political game – both inside and outside the Korean Peninsula. Given the current showdown involving North Korea, it might seem naïve to expect that the project would get off the ground before the basic differences of opinion on the nuclear issue and the overall status of the DPRK are resolved. The sudden cancellation of the test run seems to support this point of view. But is that really so? After all, North Korean-South Korean, China-DPRK, Russia- DPRK cooperation has flourished despite the hostilities. Still, a compromise will have to be found between diverging economic and political interests of the major players in TKR-TSR project. What are these divergent interests?

For North Korea the railroad project is of great strategic importance. First, linkage with South Korea, China, Russia and the European Community would allow it to become an important international transportation hub. That in turn would increase its ability to resist volatile pressure from the US and its allies. Second, the idea of North-South joint efforts in international transportation does not seem to be at odds with the North Korean policies on relations with the South and unification. Economic cooperation without political concessions would benefit Pyongyang and increase its international standing. It would also be in line with Pyongyang’s tactics of attempting to alienate Seoul from Washington. Third, implementation of the project would result in upgrading of the entire decrepit DPRK rail network – the sorry state of which is seen in Pyongyang as a major stumbling block on the way to economic recovery.

Fourth, the revenue from transit – which would come almost without any additional expenses – would be very welcome in Pyongyang, although the temptation to try to achieve political pressure by abusing the power of ‘putting the red light’ on the railroad might be too strong to resist at times. However, such an interruption of the transportation system would come at a price. Fifth, the choice of transit alternatives is a good opportunity for Kim Jong Il to play his father’s favorite balancing game and have China and Russia at loggerheads.

However, North Korean conservatives fear that foreign trains running through the DPRK might contribute to the erosion of the regime, or even be used as an espionage/subversion instrument. North Koreans became very suspicious when they noted the priority Seoul placed on information about their railroads within the framework of the trilateral Russia-DPRK-ROK consultative mechanism. The military establishment seems to strongly oppose the route that runs through the sensitive areas of the country. Thus the most logical route, one crossing the DMZ in the center of the country in the vicinity of Chorwon (Kyongwongson) and joining the East Sea (Donghae) line further north, was excluded by North Koreans from negotiations. Such concerns, taking into account the current ‘semi-siege’ situation the DPRK finds itself in, would seem to outweigh any potential benefits. Hence North Korea’s current passivity toward the proposal. The refusal of the North Korean military to approve the agreement on safety measures, which was a background for cancellation of the test runs, is indicative of the extent of their resistance to the project itself.

Inside the ROK connecting the railroads between North and South has become a highly emotional and contested issue, while the problem of the subsequent extension of the route to reach Europe is largely seen as a matter to be dealt with in the future. That is why present discussion in the ROK on possible routes and on the financial and economic aspects of the Trans Korea-Trans Siberian rail (TKR-TSR) transit project is rather subdued. I believe this to be a short-sighted approach. The decisions made today will have significance not only for the two Koreas and their interaction but also for the geopolitics and geoeconomics of Northeast Asia as a whole, and it is South Korea that should carry primary responsibility for these prospects. They eventually will bear the greatest expenses – but reap most of the dividends – so it is high time for the South Korean head to be pulled out of the sand!

The US seems not very happy with the idea of the project and shares the concerns of South Korean conservatives about ‘opening the door to the enemy’ by eliminating physical barriers between the North and South. Even before the present nuclear crisis unfolded, an American general stated in November 2002 that the inter-Korean rail link could become ‘an invasion corridor’ for the North. Oddly, this mirrors the view of the North Korean top brass. Also, reconnecting South Korea to the continent would increase the influence of China, Russia or both on the ROK, as well as increasing South Korea’s interdependence with the North. This would hardly be in US interests. It is possible that US opposition will become more vocal if the project progresses.

It seems that Japan (if and when its relations with the DPRK become less hostile) would most likely not oppose the project as the route could provide for the freight transportation of Japanese goods to Europe and thus be a sensible investment. The EC has shown interest in the project – both from an economic and a political point of view – as it would help bring North Korea into the open and encourage it to honor internationally acceptable behavior patterns.

Beijing sees the inter-Korean rail link as an important tool to stabilize the security situation on the peninsula while simultaneously increasing its own clout throughout the region. Freight through North Korea would provide a new source of income to the DPRK, stimulating its movement towards Chinese-style economic reforms and openness, and demanding more predictable behavior. From the economic point of view China is eager to reinstate the rail link between itself and its increasingly important trade partner South Korea as well as attain a new transport access corridor to the Pacific. For its purposes, the Western (Kyonguison) transport corridor linking Seoul and Pyongyang to the Trans China railroad would seem to be particularly important for handling the swelling volume of bilateral trade with the ROK. There are several factors, however, working against this route becoming the basic ‘iron silk road’ to Europe. First, already existing congestion on the railroads of Northeast China would inhibit the transportation flow. Additionally the multitude of borders would require significant time for the formalities of customs (closer does not necessarily mean cheaper and faster). However, as no alternative route currently exists, transit freight from Korea – even via China – would eventually be funneled into the Trans Siberian road (TSR) near Baikal – leaving a considerable portion of the TSR unused. However, that would not necessarily mean a much-reduced income for Russia, since it could use its monopoly to determine transit fees.

Russia was very active in initiating the TKR-TSR project, seeing it as an opportunity to strengthen its position in the region, its role as a Eurasian bridge, and a chance to create a source of revenue for upgrading both the Trans Siberian railroad and adjacent lines. After Kim Jong Il’s famous railroad journey by this route in 2001 and subsequent bilateral discussions with Russian President Putin, the project became the centerpiece of Russian-North Korean cooperation. It is also high on the agenda of Russia-ROK relations. The Russian state-run railroad company RZD has conducted intensive feasibility studies inside the DPRK and is eager to continue.

Russia has succeeded in creating a unique trilateral consultative mechanism with the DPRK and ROK. After several working-level discussions, an unprecedented ministerial-level meeting took place in Vladivostok on March 17t h 2006, where the three parties agreed to start modernizing the TKR in the area between the Russian-DPRK border and the port of Rajin in the far Northeast of the DPRK (now part of the Rason free economic zone) which is on the Eastern (Donghae) route. In the Soviet era, the route was widely used to transport goods from the Pacific to the interior of Russia, but then it was destroyed.

There are a number of problems to be solved to insure the future operability of the transit route. The most worrisome is the question of the relevance of the Donghae (East Sea) line, which is favoured by Kim Jong Il. Without progress on the Donghae line, North Koreans will be unwilling to prepare to do anything about the Kyoungui (western) line, being wary of the possibility of further rapprochement between the ROK and China, to the detriment of Pyongyang’s interests.

The Donghae line would be costly to build (in thebillions of dollars range). Just to renovate the existing line with the DPRK would cost, according to Russian feasibility studies, at least $2-3 billion, and in South Korea at present the line goes nowhere much and a. new route to Pusan would have to be constructed. For that, land would have to be purchased from private owners along the East sea coast.

Kim Jong Il’s preference for this line seems to originate from his desire to get as much as possible of DPRK railroads upgraded in the framework of the project and to create a Russian alternative to the Chinese rail connection.

However, if this route proves to be a non-starter, Kim Jong Il could still overrule his generals and approve the more logical Kyongwon (middle) route. That would facilitate investment since much smaller amounts would be required compared with the Donghae line.

An international consortium for this project (advocated by Russia and now supported by both North and South Korea) is not unthinkable. Incidentally, apart from investment in construction, Russia could also agree to write off DPRK debt in return for some property rights such as shares in the consortium, making it doubly attractive for both countries.

To sum up, even after the North-South line opens to traffic, we are still at the very early stage in the process of working out an agreeable concept for the ROK-European transit route. Now is the time to intensify the search for a way to harmonize the various interests involved and reach a shared view of the future.

Georgy Bulychev is the research director of the Center for Contemporary Korean studies at the Russian Institute of International Relations and Global Economy (IMEMO). He wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted at Japan Focus on May 24, 2006.