Binational Pearl Harbor?

Tora! Tora! Tora! and the Fate of (Trans)national Memory

Marie Thorsten and Geoffrey M. White

The fifty-year anniversary of the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between Japan and the United States, signed on January 19, 1960, was not exactly a cause for unrestrained celebration. In 2010, contentious disagreements over the relocation and expansion of the American military presence in Okinawa, lawsuits against the Toyota Motor Corporation, ongoing restrictions on the import of American beef, and disclosures of secret pacts that have allowed American nuclear-armed warships to enter Japan for decades, subdued commemorative tributes to the U.S.-Japan security agreement commonly known as “Ampo” in Japan.1

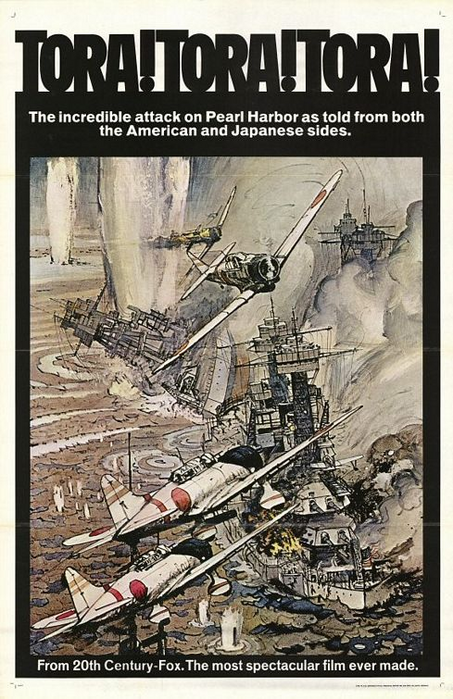

In this atmosphere it is nevertheless worth recalling another sort of U.S.-Japan pact marking the tenth anniversary of Ampo, the 1970 historical feature film, Tora! Tora! Tora! (dir. Richard Fleisher, Fukasaku Kinji and Masuda Toshio).2 Whereas the formal security treaty of 1960 officially prepared the two nations to resist future military attacks, Tora! Tora! Tora! unofficially scripted the two nations’ interpretations of the key event that put them into a bitter war, the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941. Although conceived by the American film studio Twentieth-Century Fox as a way to mark a new beginning for the two nations, certain popular opinions at the time, particularly in Japan, regarded Tora! Tora! Tora! as a cultural extension of the unequal security partnership.

On the American side, Pearl Harbor has come to wield such iconic proprietorship that it may seem inconceivable that the authorship of such pivotal memory could ever be shared with the former enemy. Airing his vehement disapproval over whether to build a mosque near the site of the World Trade Center attacks, a controversy preoccupying Americans in 2010, political stalwart Newt Gingrich (former Republican Speaker of the House of Representatives), analogized, “We would never accept the Japanese putting up a site next to Pearl Harbor.”3 In the realm of education, a series of teacher workshops that had brought American and Japanese educators together to discuss approaches to teaching about Pearl Harbor was recently brought to an abrupt end when an American participant complained to federal sponsors that the program amounted to “an agenda-based attack on the U.S. military, military history, and American veterans.”4 The fact that this criticism, directed to the federal funding source (the National Endowment for the Humanities as well as the U.S. Congress) quickly found receptive audiences through political blogs and veterans groups’ listservs suggests an insecure, zero-sum mentality in which listening to other controversies and points of view somehow erases dominant narratives, which must then be vigilantly protected.

Nevertheless, we consider Tora! Tora! Tora! a noteworthy exception to such assumed proprietorship for its splicing together of two, mostly parallel, national productions from America and Japan. It is perhaps inevitable that such a film encountered difficulties narrativizing the events of Pearl Harbor for two national audiences—events that have been the subject of contested and shifting memory for Americans throughout the postwar period. This shift has been made manifest in the last decade through highly misguided efforts to summon Pearl Harbor memory to serve America’s “war on terror” —in the hopes of recreating American revenge, triumph, occupation and democratization of the vanquished.5

Despite its claims to tell both national sides of the attack, Tora! Tora! Tora! evoked discussions of genre and accuracy in cinematic representations of war and nation, with much interest, especially in America, over the “American view” and the “Japanese view.” Japanese critics were less concerned about the film’s reference to Pearl Harbor in 1941 than the politics of the 1960s framing the film as an expression of unequal bilateral relations or glorification of state violence. While there is validity to such concerns, the film also offered a unique space for integrating narratives not entirely reducible to exigent security matters. Especially in response to the Gingrich statement above, we express some cautious appreciation of the film’s gesture not only of bridging the stories of both nations but also acknowledging mistakes made throughout the chains of command in both the United States and Japan leading to Pearl Harbor attack.

Tora! Tora! Tora!’s screenplay was adapted from the extensive writings of historian Gordon Prange, including an early work titled, Tora! Tora! Tora!6 and Ladislas Farago’s The Broken Seal (1967). Though Prange died in 1980, his former students, Donald M. Goldstein and Katherine V. Dillon, published his meticulously documented oeuvre on Pearl Harbor as the posthumous At Dawn We Slept: The Untold Story of Pearl Harbor (1981), widely considered an epic, unparalleled book compiling Prange’s thirty-seven years of research. After researching both national perspectives and claiming “no preconceived thesis”7 (and originally intending to do primarily the Japanese side), Prange’s “reflective” rather than “judgmental” conclusion, expressed by Goldstein and Dillon, was that there were “no deliberate villains”:

[Prange] considered those involved on both sides to be honest, hardworking, dedicated, and for the most part, intelligent. But as human beings some were brilliant and some mediocre, some broad-minded and some of narrow vision, some strong and some weak—and every single one fallible, capable of mistakes of omission and commission.8

Writing mostly in the post-Occupation years yet before the 1980s, Prange’s Pearl Harbor books including At Dawn assumed a “happy ending on both sides” marked by peaceful relations and the rise of the Japanese economy under the American military umbrella.9 As technical adviser to the film version of Tora! Tora! Tora! Prange’s signature themes of communication failures, mutual mistakes and diffused responsibility are prominent.

For many Japanese citizens during this time, however, the inescapable backdrop of the mutual security treaty acquired a narrative power of its own, metaphorically coding the film in terms of the unhappy hegemony of one side’s overwhelming military superiority. There are no indications of the filmmakers making an Ampo statement willfully, though certainly the American power equation coupled with the gravitas of a major Hollywood studio conditioned audiences and critics to connect the dots to American military dominance. Major events shape people’s understanding of the world around them according to the storylines they half-consciously absorb and retain. Associating time periods to social understanding of films, we are attentive to the narrative power of key events that shape societal world views, whether Ampo in Japan, or Pearl Harbor more generally as a moment that, in one Admiral’s view, “never dies, and no living person has seen the end of it.”10

Plans for launching Tora! Tora! Tora! were announced to the Japanese public in November1966 as involving the renowned filmmaker Kurosawa Akira and Kurosawa Productions’ manager, Aoyagi Tetsuro, working with Twentieth Century Fox. Kurosawa and two other writers who often worked with him, Oguni Hideo and Kikushima Ryuzo, wrote the Japanese portion of the screenplay over the course of nearly two years. Larry Forrester, a British journalist and novelist, wrote the American portion of the screenplay. According to Japanese sources, the screenplay rights were owned by Fox. As a result of a conflict explained below, Kurosawa was replaced by directors Fukasaku Kinji and Masuda Toshio. Tora! Tora! Tora! often brings up memories of the war’s “backstage” during the production process, which, though usually referring either to the firing of Kurosawa and/or the film’s associations with unequal bilateral relations, also reflect the inevitable politics of translation encountered in transnational coproductions.11

Feature vs. Documentary: Blurred genres

Given the conventional wisdom that Japan and the U.S. maintain divergent national memories of the Pearl Harbor attack–America remembers, Japan forgets–we are faced with the puzzle of how filmmakers from the two nations merged their creative efforts. To add to the irony, the film enjoyed relatively greater box office success in Japan than in the United States. Although a feature film, it inevitably produced critical debates about historical truth and the politics of national war memory.12 Although the Pearl Harbor attack has generated a significant body of both documentary and feature film production, a close examination of both types of films suggests that these genre distinctions have little, if any, significance for cinematic claims of historical veracity. Though classified as a feature film, Tora! Tora! Tora! can easily be viewed as a comprehensive “documentary” for its relentless attention to detail and causal sequence. In contrast, the first documentary produced about Pearl Harbor, December 7th, an official production of the U.S. Office of War Information (and recipient of a 1943 academy award for best short documentary), uses such devices as deceased American sailors speaking from the grave to tell its “complete and factual” story.13

The ambiguous area between documentary and fiction has been well noted.14 Elizabeth Cowie explains that fictional films offer “narrative causality and psychological motivation,” whereas documentaries provide “the terms [for] believability” through the authority of the narrator and factual evidence. In viewing documentaries, audiences expect both believability and psychological resonance, but fill in the gap between their expectations by reaching for fantasy and symbolic imaginaries.15 Whether documentary, feature, newsreel, or “docudrama,” films of Pearl Harbor draw from narrative structures that plot the bombing as a moral parable that speaks to Americans (or Japanese or others) about the lessons of war. The force of this mythicized story of Pearl Harbor accounts for much of the discursive similarity of Pearl Harbor films across diverse genres and, to an extent, through shifting historical circumstances.

Pearl Harbor Films through Time: 1940s through 1970s

Narratives of history mutate as they cross national as well as temporal borders.16 Just as analyses of key anniversaries of Pearl Harbor have plotted their shifting significance for American audiences, it is possible to consider the fate of Pearl Harbor films at different moments in national time.17

1940s, 1950s: World War II, as it is known in the U.S., was the first worldwide conflict in which cinema, primarily newsreel and Hollywood film, played a dominant role in shaping public understanding of the war.18 A singularly dramatic event that drew the United States into global conflict, the attack on Pearl Harbor became known immediately through photographs in Life magazine and images run in Hearst newsreels within weeks of the attack.19 The spectacular images of exploding and burning battleships, captured in both still photographs in national magazines as well as in a limited amount of film footage, quickly became the iconic signature of Pearl Harbor—images that continue to focus Americans’ “flashbulb memory” of America’s only incident of “foreign attack” since the burning of Washington D.C. in the war of 1812.

In both Japan and the United States, the bombing of Pearl Harbor was quickly taken up by the machinery of state-sponsored image making. Immediately following the attack, a U.S. naval film unit under the direction of John Ford and Gregg Toland began work on an official American documentary that could be used to support the war effort. But photographic and newsreel images of the attack had circulated so quickly that the filmmakers had to come up with something new for audiences who had already seen most of the footage taken during the bombing.20 The film they made, December 7th, mixed documentary and feature film styles in ways that ultimately defeated the project, resulting in suppression of the 83-minute film never released because of objections by U.S. Navy and Department of War reviewers. This film begins with a fictionalized “Uncle Sam” character and includes an extended dramatized depiction of spying by local Japanese Americans (undeterred by the fact that no cases were ever recorded). Ford later salvaged a shorter version of December 7th for use in official “moral(e)-building” programs and it was this version that received the Academy Award for ‘best short documentary’ in 1943.

Despite its troubled origins, this first official American film of the bombing exerted a strong influence on subsequent cinematic depictions of Pearl Harbor. Because only a small amount of film was shot during the attack itself (until recently the only footage that was used in the bulk of Pearl Harbor documentary consisted of about 200 feet of film, or six minutes, shot by two cameramen and some additional footage of damage in urban Honolulu), December 7th undertook extensive model-building, recreations and staged re-enactments with special effects to capture the drama of combat. Those scenes, springing from the imagination of Gregg Toland and his crew, were reused in numerous documentary and feature films during postwar decades. They were “recycled as reality by countless, naive documentary filmmakers, blurring the lines between fiction and documentary in ways Toland and Ford couldn’t have predicted.”21 Indeed, the influence right through to the 2001 Disney epic feature Pearl Harbor is clear, with specific scenes and camera angles reproduced faithfully, as if history was at stake.

The Japanese made only a minimal film record of the attack, favoring still photographs taken from the attacking planes that were incorporated in a variety of films and publications.22 A newsreel report on the attack was released in December 1941, using martial music to accompany the “march of battleships.”23 Official Japanese filmmakers dealt with the relative absence of footage just the way that Toland and Ford were doing across the Pacific—using models and miniatures to construct an elaborate set where the attack could be simulated in the documentary The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya (1942). Pearl Harbor was also the subject of the first feature length Japanese animated film in 1943, Momotarō’s Sea Eagle (Momotarō – no umiwashi)—a 37 minute black and white epic film telling the story of the attack using animal characters led by the children’s story hero Momotarō. As the liner notes proclaim, “To the tune of Hawaiian music, they rush into the enemy harbor at dawn, beginning an exciting bombing and torpedo attack.”24

Of course, numerous Hollywood films, such as From Here to Eternity (dir. Fred Zinnemann, 1953), have utilized elements of the Pearl Harbor story in building their own narratives. Films produced during the war itself incorporated references to Pearl Harbor and some, like Air Force released in 1943, worked in extended scenes of the attack to dramatize the outbreak of war and set the scene for longer stories of American heroes (and Japanese villains) at war. Major feature films would take Pearl Harbor as their subject, rather than as backdrop to other forms of cinematic storytelling. As the war moved further into the realm of an imagined national past, Pearl Harbor acquired an even larger, mythic status, as a signpost in national memory that is repeatedly redeployed to meet changing circumstances.

1960s, 1970s: How then, to account for the willingness of American and Japanese filmmakers to work together just a quarter-century after the attack? To begin with, except when used as brute propaganda, war films in general often use affective, technological and strategic components to attract “war buffs” and technophiles regardless of nationality. Tora! Tora! Tora! deployed all such devices, along with the somewhat anodyne humbling of national identities achieved through the Prange-ian assertion that “they all made mistakes.” Yet the film also enabled, some feared, the forging of a more forgetful binational identity serving the mutual security alliance. The forgetting began less than one month after Japan’s surrender to transform the nation from enemy to friend. The Marine Corps publication Leatherneck Magazine morphed its infamously simian cartooning of Japan during wartime into a “smiling Marine with an appealing but clearly vexed monkey on his shoulder, dressed in the oversized uniform of the Imperial Navy.”25

The period from the late 1950s through the early 1970s, characterized by intense Cold War diplomacy, atmospheric nuclear testing, and wars in Korea and Vietnam, offered a period for strengthening relations between America and Japan, among officialdom at least. The war was past and the intense trade friction era was yet to come. Japan was proving its loyalty to U.S. global ambitions in the Korean and Vietnam Wars. Official discourses in both countries needed to forge a strategic code of friendship. Japan would be made into a pivotal Cold War ally, a capitalist partner in the global war against communism, a friendly place of rest and relaxation for American servicemen in Asia. America’s security umbrella in turn was promoted in Japan, both to compensate for Japan’s own (imposed) military allergy and to give the defeated nation a new legitimacy in global markets. The 1960 US-Japan Mutual Security Agreement required Japan to host American bases in Japan with the promise of the return of Okinawa (accomplished in 1972). Japan was allowed to develop its own Self-Defense Forces and continue its role as a military procurer for American wars in Asia. Meanwhile, this was also the so-called “golden age” of Japanese cinema, and filmmakers hoped to exploit each other’s lucrative markets.

The masses were less convinced of the bilateral arrangement. Japanese demonstrations against America’s hand in the remilitarization of their country had already begun in the 1950s, after the first US-Japan Security Treaty in 1951 was signed as part of the San Francisco Peace Treaty process bringing an end to the Allied Occupation. Both leftists and rightists saw this earlier treaty giving permission to America to keep bases in Japan as a violation of sovereignty. Leftists also knew it betrayed the very antiwar principles that Americans themselves scripted into their Constitution. Anti-base movements merged with the anti-nuclear movement, ignited further by the accidental irradiation of Japan’s Lucky Dragon fishing crew during America’s Bikini hydrogen bomb test in 1954. By 1960, when the Treaty recognized today was negotiated to return Okinawa but continue the expansion of America’s bases and troops, the demonstrations had peaked as a multi-layered, socially diverse peace movement. Protesters decried the American presence in Japan as anachronistic extraterritoriality, and vented outrage at violations against women victims of sexual crimes committed by base personnel. They opposed global nuclear weapons testing, with legitimate concern that Japan would be targeted in a possible Cold War conflict.26 It was in this atmosphere of intense social unrest against the U.S.-Japan military alliance from the 1950s through the early 1970s that Japanese critical reaction to the binational narrative of Pearl Harbor is best understood.

I Bombed Pearl Harbor

Another film from the Ampo era was Japan’s more obscure 1960 Japanese film Hawai Middouei Daikaikūsen: Taiheiyo no Arashi (lit., The Sea and Air Battles of Hawaii and Midway: Storm on the Pacific), released in the U.S. in 1962 under several titles (Attack Squadron, Kamikazi, Storm Over the Pacific), most commonly I Bombed Pearl Harbor.27 Even if somewhat difficult to find, I Bombed Pearl Harbor is one of the only Japanese war films known in the United States among war history buffs (as distinct from art house audiences to whom the more coherently pacifist films such as the Burmese Harp and Black Rain are well known). Its marketing across both nations warrants some critical comparison with Tora! I Bombed Pearl Harbor was directed by Matsubayashi Shuei, whose fame was eclipsed by the Special Effects Technician, Godzilla‘s peerless creator Tsubaraya Eiji. Given their experience with monster movies, including Godzilla, as well as other war movies, it is unsurprising that they favored technological inscriptions in the cinematography. Matsubayashi was also a Navy veteran. This film is also notable for its mega-star, Mifune Toshiro, who acted the part of Admiral Yamamoto.

|

I Bombed Pearl Harbor (Taiheiyō no arashi), 1960, advertised in the US Taiheiyō no arashi, 1960, in Japan |

I Bombed’s three-act drama starts with the Pearl Harbor attack, cuts back to what is happening to the characters’ home lives in Japan, and ends with an extended treatment of the defeat of the Japanese invasion fleet at Midway, widely regarded as the turning point in the war. The extended treatment of the Midway battle—a military and national debacle that sealed Japan’s fate, even if it would take over three years of catastrophe to finalize it–sets up a tragic narrative that frames the film’s multiple parts. Within this framework more personal stories can be told, depicting humanized individuals caught in the machinations of geopolitics. The film concludes with a coda that has been a dominant theme in Japanese reflections on the Pacific War, questioning the militarism and patriotism that took citizens into war- an entirely different ending from the prototypic American moral imperative for Pearl Harbor (“be prepared,” fight back, and overcome).

Yet as in other films, there are enough layers and ambiguities that I Bombed yields multiple interpretations. As some critics have noted, this narrative of inevitable defeat also creates a context for accentuating the actions of Japan’s loyal young men as noble self sacrifice, an impulse that has received full expression in recent cinematic depictions of the sacrifice of young kamikaze pilots such as Firefly (Hotaru), directed by Furuhata Yasuo (2001) or For Those we Love (Ore wa, kimi no tame ni koso shini ni iku) scripted by Ishihara Shintarō (dir. Shinjo Taku, 2007).28

Despite its blockbuster special effects and all-star cast, I Bombed Pearl Harbor is barely known, even in Japan. Kinema Junpō reported that the film was popular when it first opened in the year of Ampo, 1960. High-profile film critic Yodogawa Nagaharu ‘s critique for that publication may have been responsible for the film’s evaporation from the war genre pantheon, as we failed to find any other reviews beyond his. While praising Tsubaraya’s skills, he was profoundly skeptical of the Hollywood-ization of the narrative: the need to make everything big, violent and expensive. (Ironically, Yodogawa subsequently became known for his infatuation with Hollywood and promotion of American blockbusters on television.) Yodogawa’s main concern lay with the unintended consequences of the narrative, how young people with no experience in war would react to it, if they might put on uniforms and go off to war as if it were “the most interesting big game” humanly possible. Just to tell the story of the battles of Pearl Harbor and Midway would be a reasonable thing in itself, he acknowledges, but in Japan that story might easily become a template for a Pacific War Chushingura – the classical story of botched vengeance told thousands of times in theatre, narrative and film. I Bombed Pearl Harbor however, is not even worthy of such a dubious prospect, he lamented, since it is nothing but a “spineless umbrella,” a spectacle of special effects and fireworks.29

Yodogawa hoped for a stronger human component, arguing that if the film had better dramatized the war’s effects on more ordinary people on the home front, such as the scene where the protagonist returns to see his mother and get married, then more violent war scenes could have been spared. He was skeptical about the miniaturized special effects and found the ending sloppy as well; the whole film was just “playing around”.30

Even the low level of response to I Bombed Pearl Harbor in Japan seems substantial in comparison with the near invisibility of the film in the United States. When distributed in the United States, the film was always billed as a story of the bombing of Pearl Harbor “from the Japanese perspective.” The promotional notes proclaim, “. . . . these are the events of the war seen through the eyes of the Japanese.” At the time of release in the U.S., one of the film’s posters depicted a large image of the attack pilot’s face and asks, “Where were you on December 7, 1941? This man was in a Japanese Zero over Pearl Harbor.” While this strategy of promoting the film as a glimpse into the perspective of former enemies might intrigue those interested in war history and technology, it did not engage mainstream American audiences.

A cover blurb for the video of I Bombed concludes with a note that the film’s realistic recreations of battle scenes make the film “especially interesting for history buffs.” As is also the case for Tora! the film clearly has a high techno appeal for audiences interested in war history and the fine details of special effects productions. The promotional liner touts the film as a “Technicolor epic that holds the record for most ships destroyed per minute of film.” There is, then, likely to be little overlap between the audience for this film and those interested in antiwar dramatic films such as Kobayashi Masaki ‘s trilogy The Human Condition, Burmese Harp, or Fire on the Plains.

Tora! Tora! Tora!

If I Bombed… received limited distribution in the United States, Tora! Tora! Tora!, released a decade later, quickly gained a place in cinematic history as a classic of its genre. Though poorly reviewed on release, it developed enormous staying power, with sales boosts at each major anniversary. A survey at the USS Arizona Memorial in 1994 determined that for Americans the film was the most common source of popular knowledge about the Pearl Harbor attack.31 Whereas for later generations this might be displaced by the 2001 feature film Pearl Harbor, the tone and structure of the film resembles closely that of the short documentary film shown at the Memorial itself to provide an overview of the attack and its historical significance.

Tora! required years of negotiation between Japanese and American investors, leading to parallel productions under the control of Twentieth Century-Fox edited somewhat differently for each national audience. The film cost over $25 million, a sum that was not earned back at the box office in the U.S., although the film did well in Japan.

Advertising for Tora! suggested the film would help seal the past—following Prange’s thematic that mistakes were made on both sides–and open the future:

Tora! Tora! Tora! shows the deceptions, the blunders, the innocence, the blindness, the brass minds, the freak twists. The all-too-human events that led to the incredible sea and sky armadas that clashed at Pearl Harbor.

Tora! Tora! Tora! recreates the monumental attack from plan to execution, as seen through both eyes—theirs and ours. Which is what any honest motion picture about the past must do, if it is to speak to the people of the present: the people who will make the future.32

Tora’s brochure distributed after the film’s premiere also implies that the film was governmentally approved, if not an artifact of “closure” in itself:

For several years, there was great skepticism within both American and Japanese film circles about the making of “Tora! Tora! Tora!” Yet, by summer of 1968, both governments looked favorably on the re-telling of these dramatic events and moments in history. Bitter enemies no longer, but allies in an uncertain world, they agreed that the monumental story of both sides should be told; that it contained great historical meanings for the future.33

In all probability, the extent of Japanese governmental negotiations was probably limited to obtaining consultation from ex-pilot Genda Minoru, the lead strategist of the Pearl Harbor attack, who happened to be a member of the Japanese Diet (parliament) at the time. (Prange also interviewed Genda and other Japanese veterans for his books.) U.S. governmental approvals focused on obtaining (and using) vintage war props and gaining permission to shoot the film on the same military bases in Hawai‘i where the attack occurred.

Conceived by Darryl Zanuck of Twentieth Century Fox studios as a Pacific variant of his epic The Longest Day (1962), which had been a major box office success, Tora! was a big-screen spectacle depicting historical events with fine detail. In this regard, as a portrayal of history, Tora! may have succeeded too well, so well that in retrospect it became rather one of the most detailed and complete “documentaries” ever made on the subject of Pearl Harbor. The Motion Picture Guide agreed, saying “TORA! TORA! TORA! is probably as accurate a film ever to be made about the events that led the United States into WWII…”34 The structural symmetries between the American and Japanese parts in the film’s narrative are striking, showing the mishaps on both national sides that, when spliced together, make for an amazing litany of “what ifs.” The American side details the operation and failure of communications and military technology involving codes, cables, telegrams, and radar.

Here the human details stand out, unlike most postwar (and Cold War) American narrations of the attack that coalesce into purely strategic necessities to “Remember Pearl Harbor,” i.e., be prepared. The Japan production portrays the intense emotions of the leaders, generational conflict, inter-service rivalries between the Army and Navy, and feelings that the attack was a mistake – the latter embodied particularly in the figure of Yamamoto. Japan’s hubristic attack culminates in the fictional Admiral Yamamoto uttering the famously fabricated line, “”I fear all we have done is to awaken a sleeping giant and fill him with a terrible resolve.” (A slightly different version was copied into Disney’s Pearl Harbor mentioned below.) By depicting the tragic nobility of Yamamoto, a strategist with his own American experience and sensibility, the film reproduces one of the primary means through which postwar America came to reconcile its visions of Japan as wartime enemy with Japan as postwar ally. As we shall see, this aspect may have been missed by the first cohort of American viewers, while despised by Japanese critics expecting a stronger censure of leaders.

Twentieth Century Fox revealed much of the research for the film in its production notes. It seemed particularly important to proclaim this aspect of the film—its historical accuracy and authenticity—for the Japan side:

According to Japanese film trade publications, no other film in the history of the nation’s industry received “such elaborate and meticulous research.” Poring over government records, examining old photos, consulting with the family of the late Admiral Yamamoto, digging out the plans and specifications of naval aircraft, tracing the architect’s blueprints for the battleship Nagato and carrier Akagi, researchers delved into every possible facet of the period to meet official Tokyo demands that the motion picture be authentic.”35

Kurosawa Debacle: The War-Within-the War Story

While some Americans voiced reservations about incorporating a Japanese view of Pearl Harbor into Tora!, their reservations are minor when compared with the vituperations of some of Japan’s own critics, which began years before the film was released. The actual narrative of Tora! may never be as well known as the political maneuverings that took place behind the scenes, a war-within-the-war-story, involving legendary director and screenwriter, Kurosawa Akira.

By the mid-1960s, when Kurosawa entered a contract with Fox as screenwriter and director for the Japan side of Tora!, he was already an internationally acclaimed filmmaker. He had directed 23 films and won first prize at the Venice Film Festival in 1951 for Rashomon. Kurosawa’s correspondence reveals a commitment to the ideals of the binational coproduction, saying that although Americans thought Japanese were an “inferior race” and that Japanese accused Americans of being “hostile,” there was really only the “smallest difference” in their ways of thinking. Though such sentiments are consistent with the director’s renowned humanism, Abé Mark Nornes quipped that they might have been his “famous last words.”36

In the 1960s Kurosawa began to think about expanding his international résumé, mainly for financial reasons. Japanese studios were becoming overly commercialized, appealing to low and middle brow taste and not willing to finance an auteur with such a known expense account as Kurosawa. He attempted to make Runaway Train (from his own screenplay) in New York, but while the film was suspended for inclement weather, Fox hired him for Tora! and Runaway Train was aborted. (It was later produced by a Soviet studio). Either film would have offered him his first chance to work with color, but he was unable to complete either film. Later, Kurosawa would explain that he filmed 27 scenes of the film and made 200 drawings for it. According to Joan Mellen, Kurosawa only worked on the filming in December 1968 and by 1969 was effectively fired by Fox.37

From the extensive treatment of this conflict offered by Abé Mark Nornes (2007), it is difficult to pin down the Kurosawa termination to friction between national factions in a botched attempt to create a seamless Ampo. One problem was Kurosawa himself, displaying such authoritarian intransigence that his crew walked off the set in protest. The larger problem with joining the two nation’s stories, however, came with the role of the translator between the very different linguistic, workplace and cultural communities. Producer Aoyagi assumed the complex job of negotiating between both nations and both studios, work involving many idealistic, yet opportunistic, perfectionist, and cross-culturally inexperienced, individuals. Certainly the American studio “deferred the typical arrogance of the hegemonizer” in not appreciating the painstaking role of translating led by Aoyagi.38

Yet Nornes also situates the incident in the larger pattern of films moving across borders through various modes of global traffic, not exclusively pinioned by geopolitical strategies. Attention often turns to various translation strategies, since “translation is built into the very substance of the moving image.”39 While Aoyagi discoursed about his role as mediator using liberal translations to prevent “Pearl Harbor all over again” (Nornes’ words), he was clearly “working both sides for selfish ends,” withholding meanings of words in communicating with either Japanese or Americans.40 One film critic who wrote several pieces on the scandal claimed the whole thing reminded him of Kurosawa’s Rashomon, since no matter how much he studied it, he still wound up with contradictory stories.41 Yet, for better or worse, we are left to speculate that the vagueness and withheld meanings contributed to Tora’s “Ampo” mentality of joining the two nations in a project that entailed mutual forgetting as well as remembrance.

As director, Kurosawa was replaced by two other esteemed filmmakers, Masuda and Fukasaku. His name is not listed in the credits of the 30-page publicity brochure, either as screenwriter, artistic advisor or director. All of the scenes he filmed were cut. American reviews of the film often did not mention his involvement.

Critical commentary on Tora! Tora! Tora!

The Asahi Shimbun, one of Japan’s leading daily newspapers, introduced Tora! Tora! Tora! as the “the film for which Kurosawa was fired for an unknown reason.” It remarked that the Japanese imperial navy had never been “so politely” filmed, and strangely so, since this was an American film, and Americans were supposedly the victims. While praising the film’s cinematography and special effects, the Asahi review nevertheless felt there was something peculiar about the fact that Tora! seemed to be cheerleading the Japanese side: “under Ampo, one might even say that the civilian American filmmakers gently extended their hands.”42

Perhaps the most scathing denunciation of Tora! Tora! Tora! was delivered by critic Satake Shigeru in Eiga Geijutsu in 1970.43 Cynically denouncing Tora! Tora! Tora! as an “enlargement of truth” (shinjitsu no bōdai), he found it suspicious that the mega-length film flaunted spectacular battle scenes and views of the imperial palace while “a certain president and the so-and so emperor are nowhere to be found.” He assailed the film’s implications of conflicted innocence on the part of the emperor and Admiral Yamamoto.44 In the film, diplomats speculate on the emperor’s anti-war stance by his reading of the poem (actually written by his grandfather, Emperor Meiji and delivered on September 6, 1941): “Methinks all the people of the world are brethren. Then why are the waves and the winds so unsettled today?”45 By denying the emperor’s culpability, and by agreeing to a security alliance that merely remolded the emperor as a living being rather than a deity, the mentality of Tora! Tora! Tora!, Satake felt, acquitted the imperialism of both America and Japan. Scoffing at the script’s references to Yamamoto’s alleged scientific reasoning or the awakening of America as a “sleeping giant,” he claimed that Tora! Tora! Tora! missed the basic point of why Japan lost the war: it wasn’t a matter of might, but rather that the war was basically inhuman: “Tora! Tora! Tora! rehashes the ‘enormously false myths’ over and over again; ergo, Japan-US relations are peaceful.”46

Whereas Japanese commentators focused on the film’s relationship to the political environment of the sixties, American critics zeroed in on the film’s failure as narrative, as cinematic storytelling, in short, as entertainment. The producers no doubt hoped that the dramatic historical events, even told in a “balanced” binational format, would, combined with the special effects of a big-screen spectacle, carry the film. It did not, as severe words from critics and poor box office showing made clear. Critic after critic lamented the absence of dramatic story in a film intent on representing historical detail. Vincent Canby, titled his review in the New York Times “Tora-ble, Tora-ble, Tora-ble” writing, “a movie of recreated history like “Tora! Tora! Tora!” which, with the best of motives . . . , purports to tell nothing but the truth, winds up as castrated fiction. . . “Tora! Tora! Tora!” aspires to dramatize history in terms of event rather than people and it just may be that there is more of what Pearl Harbor was all about in fiction films. . . than in all of the extravagant posturing in this sort of mock-up.47 The metaphor of “castration” here is indicative of the significance of Pearl Harbor narrative as an affirmation of American military masculinity embodied in the human stories associated with victory in the Pacific.

Time magazine echoed these sentiments, “No single man can be blamed, and no villains or heroes emerge from this foundering, slipshod–and hypnotic–drama. . . . Without Kurosawa, the film is a series of episodes, a day in the death. As for real men and causes, they are victims missing in action.”48 And Newsweek, referring to the film’s “cold neutrality,” took up the same line, “. . .the events themselves, however astonishing, authentic, ironic and inherently dramatic, carry a cold neutrality that belongs to history, perhaps, but not to art. Director Richard Fleischer and his squad of American and Japanese screenwriters make no interpretation of the history they recount. They do not probe the personalities at play or the cultures in collision. Instead they settle for the melodrama of a straight action film . . .”49 Life Magazine called the film an exercise in “pusillanimous objectivity in which so many questions were left unanswered that “no one was responsible for Pearl Harbor—not even the Japanese, really.”50 Note that film critic Richard Schickel here makes the very point argued by Satake and the Japanese critics, that the technographic style and the narrative impulse to create a human enemy erases any sense of responsibility or culpability among those who drove the Japanese nation to war.

Reviews and commentaries of these films inevitably became opportunities for characterizing the other’s subjectivity (and, by implication, historical sensibility). Americans especially wondered, “Just how does Japan remember the war?” But this attitude consistently overlooked internal Japanese protest against that country’s America-led (re)militarization, and the painful irony of America’s own collusion with Japanese war amnesia in the project to build an anti-Communist stronghold in Asia. The most uninformed critics often assumed that Tora! Tora! Tora! presaged Japan’s resurgent national pride. One US politician stated that the Japanese would probably cut Tora! in half and rename it “The good old days.”

Pearl Harbor Films through Time: 1980s-2011

1980s, 1990s, 2000s

To put Tora! Tora! Tora! into more contemporary perspective, films on Pearl Harbor leading up to the fifty-year commemoration of the attack (and the first Iraq War, “Desert Storm”), 1991, likely reflected the atmosphere of U.S.-Japan trade conflict in the eighties. In The Final Countdown (dir. Don Taylor, 1980), a nuclear-powered United States Navy aircraft carrier (“Nimitz”) cruises into a time warp, arriving at Pearl Harbor on December 6, 1941. Flaunting American Cold War-acquired superiority, the time travel sets up a revenge fantasy for supersonic F-14’s to “splash” down the primitive Japanese Zeros.

Then, following the ennui with US-Japan relations in the latter nineties, which came to be known as Japan’s “lost decade,” the Disney Corporation released Pearl Harbor, a major, highly anticipated “blockbuster” in May 2001. Studio publicity described the film’s melodramatic juxtaposition of children at play with attacking warplanes as “the end of innocence…” followed by, “and the dawn of a nation’s greatest glory.”

On the Japan side, in 2000, “Beat” Kitano Takeshi, a globally popular director and actor, made a far more low-profile yakuza film, Brother (Aniki), with rough allusions to Pearl Harbor. Set in contemporary Los Angeles, Kitano’s character, “Yamamoto” (after Admiral Yamamoto), invades the American drug trade. Critics were unkind to both films, although the Arizona Memorial (Pearl Harbor) may have experienced a spike in Japanese visitors owing to their attraction to Pearl Harbor’s star power.51

In 2006, with Japan once again confirmed as a “war on terror” ally, veteran actor and director Clint Eastwood developed his own binational approach to Pacific War film by making two films about the battle of Iwo Jima: first the patriotic yet reflectively nuanced Flags of Our Fathers, based on a book of the same title by the son of one of those who famously raised the American flag on Mt. Suribachi, followed by a second, Letters from Iwo Jima, using Japanese actors, Japanese language and a screenplay written by a Japanese-American, Iris Yamashita. In his review of these films Ian Buruma was taken with the effectiveness of Eastwood’s strategy of humanizing the battle histories through personal stories from both sides. He even argues that Eastwood is the first foreign director to successfully make a war film that makes cultural others [the enemy] “wholly convincing and thoroughly alive.”52

The year 2011 will witness both the tenth anniversary of the 9/11 attacks and the seventieth anniversary of Pearl Harbor, again raising questions of how narrations of that pivotal attack, and the Pacific War more generally, adapt to changing national and generational audiences.

|

Visual Ampo Culture in 2010: ANPO: Art X War (2010) film by Linda Hoaglund; USFJ “Our Alliance” manga |

With the US-Japan alliance looking more variable, how was the fiftieth anniversary of the security treaty put into visual culture? 2010 brought two contrasting examples.

First, the fact that American critics, and laypeople as well, were apparently unaware of the extent of Japan’s anti-war, anti-Ampo sentiment in the postwar period was a topic recently addressed in a documentary film by Linda Hoaglund titled, ANPO: Art X War (2010). Hoaglund, American born and raised in Japan, surveys the responses of Japanese citizens during the peak moments of massive anti-Anpo (alternative spelling) protest in the 1960s, including harsh and sometimes violent government crackdowns, with special attention to the works of diverse visual artists whose pacifist or anti-treaty expressions have been nearly forgotten by society. The security treaty continues to permit “the continued presence of 90 U.S. military bases throughout Japan, an onerous presence that has poisoned U.S.-Japanese relations and disrupted Japanese life for decades,” states the film’s publicity narrative.53 The release of Anpo coincided with growing mass sentiment in 2010, especially arising from the anti-base movement in Okinawa that brought down the administration of former Prime Minister Hatoyama, to possibly “revisit the formula on which the post-war Japanese state has rested and to begin renegotiating its ‘Client State’ dependency on the United States.”54

Hoaglund stated that in making Anpo, she hoped to emulate Under the Flag of the Rising Sun, a film directed by Fukasaku Kinji, released in 1971. Calling it “one of the best films about war ever made,” Hoaglund stated that it addressed “the fundamental relationship between the individual and the state,” a subject Fukasaku often spoke about,55 and made films about, including many bloody gangster stories and the junior high school dystopia, Battle Royale. Fukasaku, of course, was the co-director for the Japanese portion of Tora! Tora! Tora! who replaced Kurosawa, and he used his co-director fee to finance Under the Flag. Though it is safe to say that he lacked Kurosawa’s unflinching humanism and balked at the nebulous idea of pacifism,56 Fukasaku was also unlikely to have seen Tora! as a vehicle to promote Ampo given his criticisms of the state.

In sharp contrast to the tone of Anpo, the scripting of a binational visual narrative came—officially—from The United States Forces-Japan (USFJ), deploying the ubiquitous Japanese “cute” (kawai). In the USFJ manga (comic) titled, “Our Alliance: A Lasting Partnership” (Watashitachi no dōmei: eizokuteki na paatonaashipu), an androgynous doe-eyed boy named “Usa-kun” (as in USA, also usagi, Japanese for bunny) goes to “protect” the home of a Japanese girl named “Arai Anzu” (“Alliance”). Usa-kun’s heroic feat is to terminate the cockroaches in Miss Arai’s kitchen, after which the two friends discuss what they have in common: freedom, happiness and dislike of carrots. Sidebars with official policy explanations outline the two nation’s combined military and economic power.57 “Our Alliance” was apparently vetted by “all senior leadership within USFJ, representatives in the International Public Affairs Office of the Japanese Ministry of Defense, the North America desk of the Pacific Command in Hawai’i, as well as the Pentagon.” Its first installment was available for download two days before the 65th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.58

Conclusion

Far more complex in comparison to cute, metaphoric cockroaches, Tora! Tora! Tora! offers a snapshot of the cultural politics of Pearl Harbor and, by implication, Pacific War memory, as they evolve and migrate across historical epochs and national borders. It prompted vigilant wariness among pacifist-leaning critics in Japan, and evocations of nostalgia for big-screen, patriotic and technographic entertainment in the United States. At the same time, as a project that entailed binational collaboration and global circulation, it also opened up a unique discursive space for international cooperation between former enemies, unusual in the genre of big-screen war films.

We are left with conflicting images of Tora! Tora! Tora! as war or peace in its own time. The film is noteworthy for its pledge to mutuality—whether that was interpreted in the form of geopolitical aims of Ampo, Kurosawa-style humanism, or simply the marketing requirements of globalization. Meanwhile the protests of Japanese critics — that the film served as a vessel for the U.S.-Japan security alliance — speak directly to the flawed pretensions of mutual amnesia that Japan is still living with.

As a transnational production, however, Tora! Tora! Tora! at least presumed a public willing to accept different, even self-critical, remembrances of a single story. This was a marked contrast from Disney’s Pearl Harbor that drew its dramatic tension from an us-them moral imperative more unforgiving of Japan, and less willing to dwell on America’s own errors. And after 9/11, with “otherness” recast as “Islamofascism,” those with zero-sum geopolitical sentiments are more interested in insulating the solidity of national narratives. Other indications that current U.S. representations of Pearl Harbor return Japan to the role of former enemy, seen from afar, may be found in the intensely patriotic film at the national World War II Museum in New Orleans and the recent attacks on the NEH teacher program that had sought to develop an international dialogue on teaching Pearl Harbor and the Pacific War. At the same time that these developments suggest a return to a single American-centered narrative of the war, the US-Japan alliance has been mystified in a veil of cuteness.

Marie Thorsten is Associate Professor of Global Communications at Doshisha University, where she researches and teaches courses on U.S.-Japan Relations, Visual Cultural Studies and Global Education. She is the author of Superhuman Japan: Knowledge, Nation and Culture in US-Japan Relations (forthcoming, Routledge, 2011).

Geoffrey White is Professor and Chair of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Hawai‘i Manoa. He is co-editor of Perilous Memories: The Asia Pacific War(s). His co-edited volume, The Pacific Theater: Island Memories of World War II, received the Masayoshi Ohira Memorial book prize in 1992.

Recommended citation: Marie Thorsten and Geoffrey M. White, Binational Pearl Harbor? Tora! Tora! Tora! and the Fate of (Trans)national Memory, The Asia-Pacific Journal Vol 8, Issue 52 No 2, December 27, 2010.

Acknowledgments: We thank numerous individuals who have provided information on these films and discussed their significance for Japanese and American audiences. We particularly would like to mention Daniel Martinez, historian at the USS Arizona Memorial in Honolulu and John DeVirgilio, oral historian, among others whom we have not forgotten. We are also grateful to Tessa Morris-Suzuki, Abé Mark Nornes, Mark Selden and anonymous Asia-Pacific Journal reviewers for their incisive comments on earlier drafts.

Notes

1 Also spelled Anpo, an abbreviation of Anzen Hoshō Jōyaku, meaning, Mutual Security Treaty.

2 Tora! Tora! Tora! refers to the code words confirming that Pearl Harbor attack was underway. While one meaning of tora is “tiger,” this code is also believed to combine “to” from totsugeki, meaning “charge” and “ra” from raigeki, meaning “torpedo attack.”

3 Lisa Miller, “The Misinformants,” Newsweek, August 28, 2010.

4 See the updated workshop website for details: National Endowment for Humanities, “History and Commemoration: Legacies of the Pacific War,” link.

5 John W. Dower, Cultures of War: Pearl Harbor / Hiroshima / 9-11 / Iraq (New York: Norton, 2010); Emily S. Rosenberg, A Date Which Will Live: Pearl Harbor in American Memory (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003); Geoffrey White, “National Subjects: Pearl Harbor and September 11,” American Ethnologist 31(3), 2004, pp. 1-18.

6 Gordon W. Prange, “Tora! Tora! Tora!” excerpted in Reader’s Digest 83 (499) (Nov. 1963), pp. 274-324; also Gordon W. Prange, Toratoratora: Shinjuwan shūgeki hiwa [Tora! Tora! Tora!: The untold story of the attack] trans. Chihaya Masataka (Tokyo: Reader’s Digest Japan, 1966).

7 Cited in Donald M. Goldstein and Katherine V. Dillon, “Introduction” to Gordon W. Prange, At Dawn We Slept: The Untold Story of Pearl Harbor (New York: Viking Penguin, 1991), p. ix.

8 Donald M. Goldstein and Katherine V. Dillon, “Introduction” to Gordon W. Prange, At Dawn We Slept, pp. ix-x. Also see John W. Dower, Cultures of War, p. 35 for a similar cross-citation regarding Prange.

9 Gordon W. Prange, At Dawn We Slept, pp. 752-3.

10 Remarks attributed to Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, Commander-in-chief of the Pacific Fleet in Pearl Harbor who was removed from office after the attack. Citied in Donald M. Goldstein and Katherine V. Dillon, “Introduction” to Gordon W. Prange, At Dawn We Slept, p. xiii.

11 See Abé Mark Nornes, Cinema Babel: Translating Global Cinema (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007).

12 Iriye Akira, “Tora! Tora! Tora!” in Mark C. Carnes, ed., Past Imperfect: History According to the Movies (New York: Henry Holt, 1996). pp. 228-231.

13 Geoffrey White and Jane Yi, “December 7th: Race and Nation in Wartime Documentary,” in D. Bernardi, ed., Classic Whiteness: Race and the Hollywood Studio System (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001).

14 Michael Renov, The Subject of Documentary (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2004).

15 Elizabeth Cowie, “The Spectacle of Actuality,” in Jane M. Gaines and Michael Renov, eds., Collecting Visible Evidence (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.1999) pp. 30-34.

16 Lisa Yoneyama, “Critical Warps: Facticity, Transformative Knowledge, and Postnationalist Criticism in the Smithsonian Controversy,” Positions: East Asia cultures critique 5(3), 1997, p. 779.

17 Roger Dingman, “Reflections on Pearl Harbor Anniversaries Past,” The Journal of American-East Asian Relations 3: 3(1994): 279-293; Geoffrey White, “Mythic History and National Memory: The Pearl Harbor Anniversary,” Culture and Psychology 3:1 (1997): 63-88; Emily S. Rosenberg, A Date Which Will Live.

18 G. H. Roeder, Jr., The Censored War: American Visual Experience During World War II (New Haven, Yale University Press, 1993).

19 Susan D. Moeller, Shooting War: Photography and the American Experience of Combat (New York: Basic Books, 1989).

20 Abé Mark Nornes, “December 7th,” in Abé Mark Nornes Nornes and Fukushima Yukio, eds., The Japan/America Film Wars: World War II Propaganda and its Cultural Contexts (Chur, Switzerland: Harwood Academic, 1994), p. 191; White and Yi 2001.

21 Abé Mark Nornes, “December 7th,” in Abé Mark Nornes Nornes and Fukushima Yukio, eds. The Japan/America Film Wars, pp. 189-191.

22 Shimizu Akira, “War and Cinema in Japan,” in Abé Mark Nornes Nornes and Fukushima Yukio, eds. The Japan/America Film Wars, p. 46.

23 Yamane Sadao, “Greater East Asia News #1: Air Attacks Over Hawaii,” in Abé Mark Nornes and Fukushima Yukio, eds. The Japan/America Film Wars, p. 189).

24 Komatsuzawa Hajime, “Momotaro’s Sea Eagle,” in Abé Mark Nornes and Fukushima Yukio, eds. The Japan/America Film Wars, pp. 191-192.

25 John Dower, War Without Mercy (New York: Pantheon Books, 1993), p. 302.

26 Andrew Gordon, A Modern History of Japan: From Tokugawa Times to the Present (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009), sec. ed. , pp. 271-273.

27 Other “exceptions” add up to the possibility that shared memories at the Pearl Harbor site are not so exceptional. In the first place, the Japanese Buddhist Aiea Hongwanji Mission is less than half a mile away from the Pearl Harbor site, and dozens of others are not so far away in Honolulu (see Lisa Miller, “The Misinformants.”). Yaguchi Yujin studied the reactions of Japanese tourists at the Arizona Memorial in Honolulu, noting that despite their feelings of difference, as descendant of the attackers, they consider themselves “integral part of the site” (see Yaguchi Yujin, “War Memories Across the Pacific: Japanese Visitors at the Arizona Memorial,” in Marc S. Gallicchio, ed., The Unpredictability of the Past: Memories of the Asia-Pacific War in U.S.-East Asian Relations (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), p. 243). Marie Thorsten studied reunions between both Japanese and American veterans of Pearl Harbor that took place between 1991-2001. (see Marie Thorsten, “Treading the Tiger’s Tail: Pearl Harbor Veteran Reunions in Hawai`i and Japan,” Journal of Cultural Research [aka Cultural Values] 6(3), 2002, pp. 317-340.

28 Tessa Morris-Suzuki, “The War in Popular Media: redrawing the Frontiers of Memory,” presentation given at “History and Commemoration: Legacies of the Pacific War” workshop, East-West Center. Honolulu, August 6, 2010.

29 Yodogawa Nagaharu, “Taiheiyō no arashi” [I Bombed Pearl Harbor] Kinema Jumpo 1074(259) (May 15, 1960), p. 82.

30 Yodogawa Nagaharu, “Taiheiyō no arashi,” p. 82.

31 Geoffrey White, “Mythic History.” 1997.

32 Life Magazine, September 18, 1970, p. 16.

33 Twentieth Century Fox, “Tora! Tora! Tora!” (brochure) Los Angeles: Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corporation, p. 10.

34 The Motion Picture Guide, Vol. VIII, 1972-83, p. 3502.

35 Twentieth Century Fox, “Tora! Tora! Tora!,” p. 25.

36 Abé Mark Nornes, Cinema Babel, p. 38.

37 Joan Mellen, “Dodeskaden,” in Donald Richie, ed. The Films of Akira Kurosawa (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996), p. 18).

38 Abé Mark Nornes, Cinema Babel, p. 41.

39 Abé Mark Nornes, Cinema Babel, p. 240.

40 Abé Mark Nornes, Cinema Babel, p. 51.

41 Abé Mark Nornes, Cinema Babel, p. 48.

42 “Hakarikaneru seisaku ito: 20seiki fokkusu Tora•Tora•Tora” [The unfathomable production plan: Twentieth Century Fox’s Tora! Tora! Tora!], Asahi Shimbun, October 1, 1970, p. 9

43 Satake Shigeru, “Kakute nichibei doumei wa antei da: Tora tora tora, Moeru senjou” (Alas, the US-Japan alliance is secure: Tora! Tora! Tora! and Burning Battlefield), Eiga Geijutsu, November 1970, pp. 94-96.

44 Satake Shigeru, “Kakute nichibei doumei, p. 95.

45 Cited in Gordon W. Prange, At Dawn We Slept, p. 211.

46 Satake Shigeru, “Kakute nichibei doumei, p. 95.

47 Vincent Canby, “Tora-ble, Tora-ble, Tora-ble,” The New York Times, October 4, 1970, pp. 1,7.

48 Stefan Kanfer, “Compound Tragedy,” Time, October 5, 1970, p. 65.

49 Paul Zimmerman, “Remembering Pearl Harbor,” Newsweek, September 28, 1970, pp. 92-3.

50 Richard Schickel, “TTT-A TKO at Pearl Harbor,” Life Magazine, October 23, 1970, p. 20.

51 Yaguchi Yujin, “War Memories Across the Pacific: Japanese Visitors at the Arizona Memorial,” in Marc S. Gallicchio, ed., The Unpredictability of the Past: Memories of the Asia-Pacific War in U.S.-East Asian Relations (Durham: Duke University Press, 2007), pp. 234-255.

52 Ian Buruma, “Eastwood’s War,” The New York Review of Books, February 15, 2007, pp. 21-23.

53 “Press Notes,” ANPO: Art X War (dir. Linda Hoaglund, 2010), online here.

54 Gavan McCormack, “The US-Japan ‘Alliance’, Okinawa, and Three Looming Elections,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 37-1-10, September 13, 2010.

55 Linda Hoaglund, “Fukasaku film review,” Anpo Blog, July 25, 2010, online here.

56 Linda Hoaglund, e-mail to author (Thorsten), November 15, 2010.Hoaglund did the subtitling for Under the Flag of the Rising Sun as well as other films by both Fukasaku and Kurosawa.

57 United States Forces-Japan [USFJ], “Our Alliance; A Lasting Partnership”[Watashitachi no dōmei: eizokuteki na paatonaashipu]’, online here, 2010.

58 Sabine Frühstück, “AMPO in Crisis? US Military’s Manga Offers Upbeat Take on US-Japan Relations,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 45-3-10, November 8, 2010.

Bibliography

Buruma, Ian2007 Eastwood’s War. The New York Review of Books. February 15: 21-23.

Canby, Vincent1970 Tora-ble, Tora-ble, Tora-ble. The New York Times. October 4: II: 1,7.

Cowie, Elizabeth.1999 The Spectacle of Actuality. In Jane M. Gaines and Michael Renov, eds., Collecting Visible Evidence. Pp. 19-45. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Dingman, Roger1994 Reflections on Pearl Harbor Anniversaries Past. The Journal of American-East Asian Relations 3(3): 279-293.

Dower, John2010 Cultures of War: Pearl Harbor / Hiroshima / 9-11 / Iraq. New York: Norton.

Farago, Ladislas1967 The broken seal: the story of “Operation Magic” and the Pearl Harbor disaster. London: Barker.

Fox, Twentieth Century1970 Tora! Tora! Tora! California: Twentieth Century-Fox Film Corporation.

Komatsuzawa, Hajime 1994 Momotaro’s Sea Eagle. In The Japan/American Film Wars: World War II Propaganda and Its Cultural Contexts. A.M. Nornes, ed. Pp. 191-195. Chur, Switzerland: Harwood Academic Publishers.

Iriye, Akira1995 Tora! Tora! Tora! In Past Imperfect: History According to the Movies. J.M.-M. Ted Mico, David Rubel, ed. Pp. 228-231. New York: Henry Holt and Co.

Kanfer, Stefan1970 Compound Tragedy. Time October 5:65.

Mellen, Joan1996 Dodeskaden. In The Films of Akira Kurosawa. D. Richie, ed. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Moeller, Susan D.1989 Shooting War: Photography and the American Experience of Combat. New York: Basic Books.

Morris-Suzuki, Tessa2010 The War in Popular Media: redrawing the Frontiers of Memory. Presentation given at “History and Commemoration: Legacies of the Pacific War” workshop. East-West Center. Honolulu. August 6, 2010.

Neisser, Ulric1982 Memory Observed: Remembering in Natural Contexts. San Francisco: W.H. Freeman.

Nornes, Abé Mark1994 December 7th. In The Japan/America Film Wars: World War II Propaganda and its Cultural Contexts. A.M. Nornes and F. Yukio, eds. Pp. 189-191. Chur, Switzerland: Harwood Academic Publishers.

Nornes, Abé Mark2007 Cinema Babel: Translating Global Cinema. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Prange, Gordon W.1961 Tora! Tora! Tora! Tokyo: Readers Digest.

Prange, Gordon W.1981. At Dawn We Slept: The Untold Story of Pearl Harbor. New York: Putnam.

Renov, Michael2004 The Subject of Documentary. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Richie, Donald1984 The Films of Akira Kurosawa. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Rosenberg, Emily S.2003 A Date Which Will Live: Pearl Harbor in American Memory. Durham: Duke University Press.

Sadao, YamaneYamane Sadao 1994 Greater East Asia News #1–Air Attacks Over Hawaii. In The Japan/America Film Wars: World War II Propaganda and its Cultural Contexts. A.M. Nornes and F. Yukio, eds. Chur, Switzerland: Harwood Academic Publishers: 189.

Satake, Shigeru 1970 Kakute nichibei doumei wa antei da: Tora tora tora, Moeru senjou (Alas, the US-Japan alliance is secure: Tora! Tora! Tora! and Burning Battlefield), Eiga Geijutsu, November: 94-96.

Schickel, Richard1970 TTT-A TKO at Pearl Harbor. Life Magazine. October 23, p. 20.

Shimizu Akira1994 War and Cinema in Japan. In The Japan/American Film Wars: World War II Propaganda and Its Cultural Contexts. A.M. Nornes, ed. Pp. 7-57. Chur, Switzerland: Harwood Academic Publishers.

Sturken, Marita1997 Tangled Memories: The Vietnam War, the AIDS Epidemic, and the Politics of Remembering. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Thorsten, Marie2002 Treading the Tiger’s Tail: Pearl Harbour Veteran Reunions in Hawai`i and Japan. Cultural Values 6(3): 317-340.

White, Geoffrey, and Jane Yi 2001 December 7th: Race and Nation in Wartime Documentary. In Classic Whiteness: Race and the Hollywood Studio System. D. Bernardi, ed. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

White, Geoffrey M.2004 National Subjects: Pearl Harbor and September 11. American Ethnologist 31(3): 1-18

2002 Disney’s Pearl Harbor: National Memory at the Movies. The Public Historian Special Issue: Beyond National History: World War II Recollected. 24 (4): 97-115.

1997 Mythic History and National Memory: The Pearl Harbor Anniversary. Culture and Psychology, Special Issue edited by James Wertsch 3(1): 63-88.

Yaguchi, Yujin

2007 War Memories Across the Pacific: Japanese Visitors at the Arizona Memorial In The Unpredictability of the Past: Memories of the Asia-Pacific War in U.S.-East Asian Relations, ed. Marc S. Gallicchio (Durham: Duke University Press): 234-255.

Yodogawa, Nagaharu1960 Taiheiyō no arashi. Kinema Jumpo 1074(259) (May 15): 82.

Yoneyama, Lisa1999 Hiroshima Traces: Time, Space and the Dialectics of Memory. Berkeley: University of California Press.

1997 Critical Warps: Facticity, Transformative Knowledge, and Postnationalist Criticism in the Smithsonian Controversy. Positions: East Asia cultures critique. 5(3): 779.

Zimmerman, Paul D.1970 Remembering Pearl Harbor. Newsweek September 28:92-3