Okinawa’s Turbulent 400 Years

Gavan McCormack

[Japanese text available here]

This three part New Year essay was commissioned by the Okinawan daily Ryukyu shimpo and published on January 6, 7, and 8, 2009, under the title “Satsuma shinko 400 nen – “Gekijo” kokka to shite no Okinawa,” (400 Years since the Satsuma Invasion: Okinawa as ‘Theatre’ state”).

For Japanese text, carried here with permission from Ryukyu shimpo, see the headings of each section.

2009 is an especially important date in Okinawan history. It marks the 400th anniversary of the invasion and conquest of the islands in 1609 by 3,000 musket-bearing samurai from the mainland Japanese domain of Satsuma. Till then, as the Ryukyu kingdom, the islands had been an autonomous part of the East Asian “tribute” world centring on Ming China. After the invasion, the appearance of independence continued but henceforth in fact the Ryukyu kings were subject to Satsuma, and to the Edo Japanese state.

East Asia map

270 years later, in 1879, even the residual sovereignty of the Okinawan kings was finally extinguished and the islands were incorporated as Okinawa prefecture within the modern Japanese state (the Meiji state, established in 1868).

The 400th anniversary of Okinawa’s incorporation in the pre-modern Japanese state, which is also the 130th anniversary of its incorporation in the modern state, offers an occasion to reflect on four turbulent centuries, from the perspective of a territory that has uniquely been both “in” and “out” of the Japanese state. Once Japan’s remotest periphery, for long butt of discrimination and exploitation and literally sacrificed to try to stave off attack on the “mainland” in 1945, Okinawa in the 21st century is at the heart of the Northeast Asian region and, as the following essay argues, raises crucial questions over Japan’s identity and role in the world.

(1) Okinawa as Theatre State [Japanese text here]

In the late 20th and early 21st century, as in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, the old order breaks down; the new struggles to be born. On all sides there is uncertainty and flux. Then, globalization opened new routes of commerce, spread new ideas and technologies and dissolved and reformed states: China’s Ming, already in its third century, faced growing challenges and unrest; Japan, emerging from a long period of chronic civil war and a failed attempt to displace the Ming and subject Asia to Japanese rule, had begun to retreat to concentrate on developing its unique closed country (sakoku) polity; Europe was expanding vigorously, despoiling Africa and enslaving its people, colonizing the Americas and violently displacing existing Amerindian kingdoms. Capitalism and nationalism were ascendant, underpinned by war and its technologies.

400 years on, again a familiar world order crumbles and the world is in flux. Western (especially US) hegemony, and the Cold War frame that underpinned the last phase of that hegemony, fades and begins to be seen as a historical aberration; the certainty that but yesterday surrounded capitalism and nationalism crumbles. The sovereignty of states is eroded by the very globalizing forces – of capital, technology, war systems – that engendered them in the first place.

Okinawa was and is profoundly affected. Then, it was the remotest periphery, subjected within the Tokugawa system to an Edo Bakufu keen to revive the relations with Ming China that had been suspended since the Hideyoshi-led invasions of Korea (1592 and 1598), and the Satsuma domain on Japan’s southern border that had already seized control of the Amami Islands. Okinawa was to be Satsuma’s African or Caribbean colony. Now, still geographically remote, it has become politically central – for the alliance between the two global powers rests on it. Furthermore, while it is embedded in the old system of Western, especially US hegemony, its location makes it potentially a core element in a future regional and world order still only dimly visible. Okinawa would be one candidate to house some of the core institutions of a Northeast Asian concert of states. How to negotiate the present clashing of world orders is Okinawa’s problem but also its opportunity.

From Okinawa’s viewpoint, it goes without saying that 1609 is a date to commemorate but not to celebrate. Having flourished for centuries as an autonomous kingdom, thriving on commerce and culture, Okinawa was in no position to offer resistance when 3,000 Satsuma samurai, many bearing muskets (only a few decades after firearms were introduced to East Asia), sailed menacingly into their world. Within days, the court submitted and King Sho Nei and his entourage were carried off to Kagoshima. The new order that was imposed was more “modern,” rationalized and bureaucratic, than the shamanistic, ritual court world it displaced, but it was also unequal and often harsh. The kingship continued, but kings were no longer sovereign.

King Sho Nei

Post-1609 Okinawa/Ryukyu was a Potemkin-like, theatre state: Okinawans were required to pretend to continuing incorporation within the Chinese tribute world, the people ordered to speak Ryukyu dialect and forbidden to speak Yamato (ie. Japanese) language, and kings traveling to Edo (Tokyo) were ordered to wear Chinese costume. Thus the façade of independence was preserved and the prestige of the Bakufu heightened by the appearance of a foreign mission pledging fealty to it. In few states were tatemae and honne so strictly bifurcated. The anthropologist Clifford Geertz once famously wrote of the Java of the pre-Dutch colonial era as a “Theatre State,” but when he used the term he meant a state concentrating on ritual, performance, and spectacle for their own sake as the stuff of politics and expression of power. Okinawa was a “theatre state” of very different kind, required to perform theatre designed to conceal the locus and nature of political authority. Shuri Castle itself was a carefully constructed stage, all Okinawans, and especially the court, actors.

Shuri Castle, Seiden

The curtain came down on that theatre in 1879, with full incorporation as a prefecture in Meiji Japan. As the last, least, and lowest component of the Meiji state, eventually sacrificed to try to protect the “core” parts of the country and then offered to long-term US occupation by the emperor himself, there is not much to celebrate in that anniversary either.

Following American rule, in 1972, the curtain rose over a different kind of “theatre state.” Nothing was what it seemed. The formal documents and instruments of power in late 20th and early 21st century Okinawa have been as deceptive and misleading as the Ryukyu expressions of tribute fealty to China in the 17th to 19th centuries.

Okinawa was required to perform Japanese sovereignty, constitutional pacifism, prefectural self-government, and regional autonomy. The reality, however, was that sovereignty was only partially returned (bases retained), the US-Japan security treaty continued to serve as Okinawa’s key charter, in effect contradicting and functioning as superior to the constitution, the reversion was secured by enormous Japanese payments. In short, it was a “purchase” rather than a “return,” and Japan was to continue paying ongoing reverse “rental” to the US to make it continue the occupation. Okinawan prefectural autonomy was as empty as the pretence of Okinawan autonomy in the 17th and 18th centuries. Crucially, Okinawa under Japan’s peace constitution retained its war state character under a condominium Japan-US command.

Throughout Okinawa’s 400 years, two sets of contradiction have persisted: between Okinawan deep-seated peace orientation and the imposed priority to war and subjection by force, and between Okinawa’s multicultural and open, Asia-Pacific universalism on the one hand and “mainland” Japan’s dominant identity construct, defined by rejection of Asia and assertion of superiority, in forms often constructed around the emperor as divine, on the other.

According to one story, probably apocryphal, as King Sho Nei in 1609 chose non-resistance to the superior force of Satsuma, he uttered the words Nuchi du takara. Whether or not he ever spoke them, these words have come to be understood as a statement of Okinawan value. Sho Nei’s submission did not mean surrender. Facing physically superior opponents, submission was unavoidable, but conscience and value were not to be appropriated by force.

In two particular respects, this essay explores the contradiction between Nuchi du takara, the affirmation of the supremacy or sanctity of life, as the expression of Okinawan values and the competing principles imposed from outside: the priority to force (in the extreme form war, and therefore death over life) on the one hand, and the priority to growth, expansion, conquest, extended under fundamentalist capitalism to involve the appropriation and exploitation of nature itself over stability and conservation, on the other.

Okinawa’s subjection to different regimes in different eras is sometimes referred to by the word “shobun,” a term that implies passivity, being acted upon or disposed of, never able to take the initiative. The question in 2009 is whether or not, with its long and bitter experience, Okinawa even now may rise above its past, articulate its life affirming message, and play a core role in establishing a sustainable community of peace and life, as a prototype, sustainable Northeast Asian community.

(2) Okinawa as a Site for Constructing Peace [Japanese text here]

Militarism has long been the bane of Okinawa – under Satsuma from 1609, the modern Japanese state from 1879, the US from 1945, and the joint US-Japan regime from 1972. Japan’s problem, and a fortiori Okinawa’s problem, is that Japanese state and official thinking on security and defense is locked within the Cold War paradigm in which the bilateral treaty relationship with the United States is so overwhelmingly important that Japan must do anything and everything required to maintain it, and it places the burden overwhelmingly on Okinawa. In the post-Cold War world (from the 1997 “New Guidelines” to the 2005-6 “Beigun Saihen” or US military realignment), the US has called on Japan to play a greatly stepped up military role as in the Iraq and Afghan wars, and governments in Tokyo have done their best to comply, deepening and reinforcing Japan’s dependence and, indeed, its irresponsibility. It is the path from the long-term dependent and semi-sovereign Japanese state of the Cold War towards becoming a full “Client State.” Japan’s pain is so much the greater because this stepped-up subordination coincides with diminished US credibility on all fronts – economic, political, and especially moral. Today’s political confusion stems at root from an identity crisis: is Japan an independent state or a “Client State?” The recent hubbub over the Tamogami affair, the latest in the battles over war memory, reflects a deep-rooted national schizophrenia.

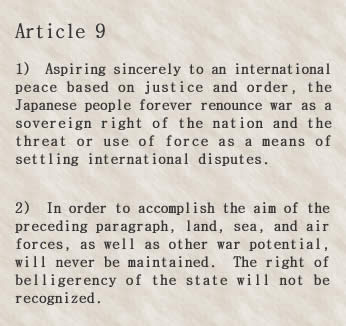

From 1947 to 1972, Japan‘s mainland “peace state” enjoyed its peace Constitution while Okinawa was severed from it as a “war state,” both, however, tied symbiotically within the US’s Pacific and Asian Cold War system. After the “reversion,” and especially under the present and ongoing Beigun saihen, the Okinawan “war state” has been reinforced, the constitution’s Article 9 steadily emptied out (for both Okinawa and the “mainland”), and the “peace” and “war” functions gradually merged. Mainland Japan becomes “Okinawa-ized,” Ampo trumps Kempo.

Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution

Okinawa’s present raison d’être in the US-Japan condominium is as a base for the projection of force and the threat of force against North Korea (some would also include China). Security under this system is assumed to rest on military alliances and weapons (including nuclear weapons – which constitute the core of the US-Japan defense system). By contrast, the basic principle of the United Nations when it was formed in 1945, and of Japan’s constitution when it was adopted in 1946, was to diminish and ultimately supplant, force as a determinant of world affairs. Both charters were consonant with the Okinawan principle of nuchi du takara.

Okinawans had imagined that “reversion” would bring them under the constitution, release them from the parameters of force and restore something of their ancient ideal of demilitarized, peaceful islands. It was not to be. The Okinawan people would never have chosen a permanent military identity, so the political challenge facing the Japanese state has been to neutralize the opposition to militarization and to secure the compliance of the Okinawan people to an agenda whose core is priority to the US alliance over the constitution, to military over civil or democratic principle, and to the interests of the Japanese state over those of the Okinawan people. Reversion, therefore, had to be built on deception and trumpery, bribery and lies. The post-reversion state used smoke and mirrors to try to create a theatre capable of deceiving and persuading on a mass scale.

US military bases on Okinawa

The deceptions were thinly concealed. What was called “reversion” was actually purchase, at a cost greater even than Japan had paid a few years earlier to compensate South Korea for four decades of colonialism; “return” was also “non-return” since the bases remained (and Japan would pay the US to continue occupying them) and those who attempted to expose the truth of the deal were pursued mercilessly and their truths denounced as lies (continuing to this day, despite the emergence of proof of their truth from the US archives). When mass discontent against the bases threatened to boil over, a new round of “reversion” was promised, but again deception was the keynote: “reversion” actually meant substitution, modernization, expansion; the scale of the new works was concealed by calling them a “heliport,” and the expression “seiri shukusho” (base reduction) was chosen to try to convey the impression that overall that was what was happening.

Since Nago was the centre of opposition and the popular struggle centred there was able to block and frustrate the state design for a full decade, 1996 to 2005, money was poured into it to try to divide, weaken and corrupt it. Nobody, even the Governor, could openly state a preference for construction of a new base for the US over preservation of Oura Bay, with its newly discovered blue coral and its dugong colony, or the adjacent Yambaru forest and its creatures, so the Governor adopted the tortuous logic of arguing that the planned Cape Henoko structure would not really be a “new” base because it would in part be constructed on the site of an existing one.

Yambaru forest

In the centuries before 1609, Okinawa’s geopolitical location was its strength; since then it has been its weakness. Outside forces have tended to see Okinawa’s location as crucial for the defense of “Japan proper” or for the projection of force against other countries. Such thinking implied distance and even hostility between Okinawa and its neighbors. Security in real terms, by contrast, depends on the forging of close, friendly, and cooperative ties with neighbor countries. Such security calls for Okinawa’s “war preparation” functions to be converted into “peace building” functions. Though the war preparations on Okinawa are directed at the Korean peninsula and the Taiwan Strait, neither official nor civil society Okinawa has, to my knowledge, ever tried to promote Okinawa as a centre for dialogue between South and North Korea, Beijing and Taipei. But is not Okinawa perfectly placed by reason of its geographical location and its uniquely multicultural history to serve as a peace centre, and as home to some of the key institutions of a future Asian community?

The Okinawan Nuchi du Takara ideal has lived in popular memory for these four centuries. Is the time not ripe now to revive and globalize such a life-affirming ideal, to insist, after 400 years, that the samisen is, after all, superior to the gun?

(3) Okinawa, Nature and Sustainability [Japanese text here]

Capitalism in 1609 was in its very early, mercantilist stage, but that same ruthless drive, expansionism, and search for profit that drove the European exploration, conquest, and colonial expansion has continued to morph through different phases, eventually becoming the dog-eat-dog neo-liberalism whose bankruptcy has become so plain today. The Edo state tried in vain to resist it and to preserve intact its own social and economic order. With the modern, Meiji state, Japan launched full pelt into its own version of expansion at all costs, first colonial, then post colonial.

While in 1609 the East Asian pre-modern, pre-capitalist order was taking shape, in 2009 what takes shape is post-modern, late- or post-capitalist. At its peak, and before the main thrust of Western imperialism, Asia’s share of global GDP was around 50 per cent. It sank to extremely low levels in the 19th and 20th centuries, but rapid growth in recent, post-colonial decades means that it is now about 25 per cent and even by conservative estimates is expected to be 50 per cent again by around 2030. Western imperialism, based on Europe’s weapons and its primacy in the adoption of industrial capitalism, was rising over Asia 400 years ago; now it recedes, but in its wake the capitalist ethic has become universal.

Asia’s share of world GDP 2006 (purchasing power parity)

In its most untrammelled, pure, market and profit-driven mode, “Chicago”-style capitalism has brought the world economy to the brink of collapse. Even more importantly, it has stretched the fabric of the earth to breaking point, putting at risk our survival as a species. The earth warms, the polar ice caps melt, the glaciers and the coral reefs shrink, the seas rise, the deserts advance, the polar bear, the tiger (and countless other species of land, sea, and sky) are endangered. Our present trajectory offers the prospect of gradual decline into chaos, punctuated by water wars, oil wars, food wars, and epidemics.

Latin America’s first indigenous state president since the European conquest, Bolivian president Eva Morales, recently spoke of the four hundred years of capitalist transition as his people saw it, noting that “everything became a commodity: the water, soil, human genome, indigenous cultures, justice, ethics, death … and life itself.”

The world’s best scientific brains have come to something close to a consensus that human activity, pumping carbon into the atmosphere at steadily increasing rates ever since the industrial revolution, must be changed. The pre-industrial concentration of carbon in the atmosphere was 280 ppm. The present figure is 387 ppm, rising at around 3.1 ppm per year. To prevent runaway global warming we must at all costs keep it below 450 ppm (many scientists think that the real tipping point is more likely to be 400 ppm – in any case now unavoidable and imminent).

Carbon dioxide emissions by country

Short of some technological breakthrough (of which at present there is no sign), we must reduce economic activity and its necessary carbon emissions, cut back on production, consumption, and waste, eliminate the unnecessary and inefficient and switch as a matter of urgency to use of renewable over non-renewable energy sources. We have to minimize consumption and restore “traditional” values of frugality. You cannot buy human community and the bounty of nature with GDP.

In such a view, recession might be not such a bad thing. Political and economic leaders in Japan, however, insist on the need to strive for 3 per cent growth. If that were accomplished, by mid-century the economy would be almost four and a half times, and by the end of the century nineteen times, greater than now. Within the remaining years of this century, i.e. roughly five generations, materials and energy inputs and waste outputs would multiply by 19 times. Such projections for any developed country are inconceivable and especially absurd in the Japanese case because the projections for population suggest steady decline, so that an aging, shrinking population will somehow have to consume at a rate more than 20 times greater than today. For Japan and the developed world zero growth – meaning zero waste, extensive material recycling, and the substitution of renewable for non-renewable energy sources – is the only politically and morally justifiable goal.

But few are the politicians anywhere bold enough to pledge to reduce their country’s GDP, or their electorate’s economic output. Despite its lunacy, conventional politics is based on the assumption that society must be organized so as to maximize production, consumption, and waste, irrespective of what is produced, under what conditions (social, ecological), and how the profits are distributed, and irrespective of the implications for the planet.

Okinawa is locked into this destructive, GDP-obsessed frame of thinking by several conditions: firstly because it is seen (and sees itself) to be “backward” in that its per capita GDP and other economic indices are below the rest of Japan and it therefore has to “catch up,” and secondly because “development” funds are seen by state bureaucrats as the best device to foster the sort of dependent, mendicant mentality in which the anti-base and environmental movements will lose momentum. “Development” has therefore tended to be concentrated on infrastructural “public works” projects that are often economically retrogressive, ecologically damaging, and debt and dependence-building.

No spectacle is sadder to the regular visitor to Okinawa than to see, in the North, the steady pressure designed to impose a huge new military complex on the quasi-pristine waters and reef of Oura Bay (and associated helipads through the Yambaru forest), and in the South, the gradual reclamation of the Awase tidal wetlands (Okinawa’s “rainforest”). In the public works-centred economy that has prevailed in Okinawa for the three and a half decades since reversion, nature has come to be seen as something to be “fixed” (by seibi) in a process that has virtually no limit, with the result that the natural environment – coral, dugong, noguchigera (the Okinawan prefectural bird) – is under siege, even as the public works-led, doken kokka-type development is now almost totally discredited elsewhere in Japan. It cannot be beyond the wit of Okinawans to find alternative ways, rooted in social need, to employ its people productively in ways relevant to addressing the present global crisis and beyond either militarism or public works type development: in regional and global peace building, nature preservation and regeneration, organic food production, sustainable energy programs, leisure (probably fusing tourism, education, art, and environment in fresh ways), aged care, health and recreation.

Oura Bay

If it were indeed the case that Nuchi du Takara principle encapsulates some Okinawan moral essence, then it is up to present-day Okinawans to spell out ways, not just for Okinawa but for humanity, to come to terms with nature, finding a way beyond both militarism and developmentalism to assert the primacy of life over war, and of sustainability and symbiosis over growth. In the early 21st century, humanity’s best hope is for a recovery of Okinawa’s Nuchi du takara values. Okinawa’s anti-base and anti environmental destruction struggles are central to the global struggle for peace and sustainability.

Gavan McCormack, emeritus professor at Australian National University, is a coordinator at Japan Focus. His most recent book is Client State: Japan in America’s Embrace.

This article was revised for The Asia-Pacific Journal and Posted on January 12, 2009.

Recommended Citation: Gavan McCormack, “Okinawa’s Turbulent 400 Years” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 3-3-09, January 12, 2009.

![Okinawa’s Turbulent 400 Years [Japanese text available]](https://apjjf.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/eastasiamap.png)