Tide Change in Saga, Japan

By Gavan McCormack

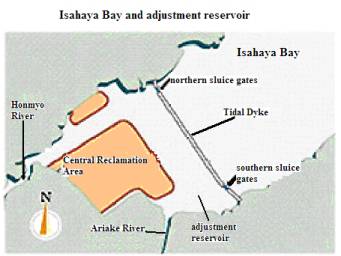

Coastal defenses in Western Japan were threatened in late August by a ferocious storm, typhoon no. 16, that happened to coincide with the highest tide of the year. At the same time, a remarkable judgment, more startling and possibly more devastating than the typhoon, emerged from a court in Saga in Kyushu. The tide of Japan’s civil society protest against the corruption, waste, and destruction wrought in the name of “public works” has long been rising. It is here that flotillas of hundreds of fishing boats have from time to time blockaded the government’s reclamation works at Isahaya Bay, drums beating and flags flying as in the righteous uprisings of feudal times, till now always beaten back by the authorities. This unexpected judicial intervention had the potential to raise the tide to the point of threatening, or even breaching, the dikes surrounding Japan’s infamous construction state (or doken kokka).

Accepting the arguments of a group of local fishermen, the Saga District Court criticized the national government for not implementing the medium and long-term reviews prescribed by a committee it had itself appointed, overruled the objections of the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport, and ordered the Isahaya Tidal Wetlands Reclamation works suspended pending a review of the whole project, even though by then it was 90 percent complete. The final outcome remains impossible to predict. The national government announced that it would appeal against the Saga court’s decision. Still, no Japanese court had ever before issued an explicit “stop” order on a government-directed public works project. The bureaucrats, politicians and construction companies that together make up the “iron triangle” of the “construction state” were at last on the defensive.

The Isahaya Tidal Wetlands Reclamation project represents in concentrated form the essence of the construction state, the developmental state that helped drive Japan’s economic growth in the 1960s and 1970s but then contributed to its implosion in the 1990s and still has the power to impose economically irrational and environmentally devastating projects. Despite Prime Minister Koizumi’s often-reiterated promise since he took office in April 2001 to “reform without sanctuaries,” it seems that no sanctuary is more sacred than that of the construction state. No project has been more characteristic of the construction state and more contentious than Isahaya, yet till 26 August none had seemed more impervious to criticism or more impossible to block.

The bay is the largest wetland component of the Ariake Sea and the most important surviving tidal wetland in Japan. Its shallow expanse is swept by a five to eight meter tide, and its silt, rich in nutrients, small organisms and oxygen, is constantly replenished by the flow of nutrient from adjacent rivers and circulated by intense marine activity. Such mudflat sites lack the dramatic beauty of the coral reef or the tropical forest, yet rival them in biodiversity. Life itself, in its myriad higher forms, is sometimes thought to have originated in just such primeval slime. The nitrogen and phosphate of rotting and decaying marine life but also of household waste, sewage and other detritus, is broken down, eutriphication suppressed, and new life created in the form of micro algae or benthic microorganisms, which are in turn then eaten by other tiny creatures such as lugworms, which in turn are food for larger creatures such as crabs, shellfish and mudskippers, upon which humans, at the top of the food chain, could then feast. Such sites are precious. Isahaya came to be known among fishermen as the “womb” or “cradle” of the Ariake Sea.

The bay used to teem with fish. Fishermen, and local residents, from children to old folk, skated over its muddy surface on wooden sleds, occasionally dipping their arms into the mud to pull out shellfish, eels, seaweed or fish, including many unique species and sub-species. Most remarkable of the 200 varieties of fish that inhabited the Bay is the bulging-eyed mutsugoro or “mudskipper,” a local variety of goby. The mutsugoro buries itself deep in the mud to hibernate during winter months, not stirring until April, and its English name derives from its habit of “surfing” along the mud with the receding tide. There are also forty-two kinds of shrimp, ninety-six of crab, three of octopus, two hundred and fourteen of shellfish, and at least three hundred different kinds of benthos (flora and fauna of the sea bottom), including some unknown till a 1994-6 survey, and eighty different kinds of lug-worm, many of them too previously unknown. A single square kilometer of tidal wetlands can produce 22.6 tons of fish-shellfish/year. Alternatively, all life-forms included, it can sustain a maximum of four kilograms of biota to each cubic meter of water, which places it on a par with coral reef. For migratory shore birds that breed in Siberia or Alaska, Isahaya is the sole stopping point for feeding and rest on the long flight to winter in South China, Southeast Asia, Australia, or New Zealand. The Showa Emperor, Hirohito, himself a marine biologist, once wrote a poem expressing the sentiment that it would be nice if somehow the myriad creatures of the Ariake Sea could be protected from the wave of development. It is a plea to which, until the judgment on 26 August, the Japanese state had turned deaf ears.

The idea of draining and reclaiming the bay was born more than a half century ago, with grandiose visions of blocking off the sea at its mouth, which is about 12 kms across, and reclaiming the whole expanse, which is roughly 17 kms deep and 76.6 kms2 in area. It looked easy enough to do. The plan, however, has had three distinct rationales, successively promoted or abandoned at bureaucratic whim while only one fundamental principle has stood firm: that the work would be done.

The first detailed plan was simply to build a huge dike and drain the whole of the bay, to create a vast stretch of new farmland. That idea, however, was blocked by fishermen, and it lost bureaucratic favor as the design for Japanese agriculture itself underwent drastic change, a mountain of surplus rice grew, and farmers were pressed to take their rice fields out of production. This plan was abandoned in 1970. The lands would still be created, but only as a by-product, so to speak, rather than as principal purpose of the reclamation.

In slightly different guise, the plan next was promoted as the “Comprehensive Regional Development Plan for Southern Nagasaki,” its rationale transformed into “multi-purpose,” but with especial weight attaching to the provision of fresh water for industrial and urban consumption. In 1982, this second version too was cancelled. The creation of large quantities of water for industry made no sense both because there was no such demand (as high-growth tapered off and grandiose regional industrialization plans collapsed) and because the continual flow of household wastewater turned the “freshwater” reservoir into a polluted pond whose quality was well below the level required for licensing for irrigation.

A third phase then began under the “Isahaya Bay Comprehensive Flood Prevention Reclamation Plan.” This time, the focus was on flood prevention. Only one-third of the bay would be drained, creating about 1,500 hectares of farmland and a 1,700 hectare freshwater reservoir, but the lands and the water would become ancillary to the plan’s main purpose, flood control. However, when heavy rains came in the summer of 1999, waters swirled again over the floorboards of homes built on reclaimed lands. As the Ministry of Agriculture’s reclamation at Isahaya proceeded, the Ministry of Construction in 1994 began work independently on its own plan to dam the Honmyo River and thereby “flood-proof” Isahaya against even a “once in a hundred years” downpour. An official of that Ministry’s River Bureau declared, with thinly concealed contempt for the massive nearby works by its rival Ministry: “This dam should make any other flood control measures redundant for this area.” During the 1980s, under this scheme fishing cooperatives one-by-one signed away their fishing rights and accepted compensation packages, feeling that they had no alternative because of the relentless bureaucratic pressure and because the works were represented as necessary for flood protection and for the protection of lives and property.

The question – what are these works for – was thus answered in various, contradictory and unsatisfactory ways but, in essence, they were because the construction state required them. As all other justifications collapsed, bizarre and outlandish ideas began to circulate: the new lands might be dubbed an “Ecopolis” and used for a series of leisure facilities – boat races, leisure farms, race horse training camp, and even a “bird sanctuary.” Critics derided this as “green paint on a bald mountain.”

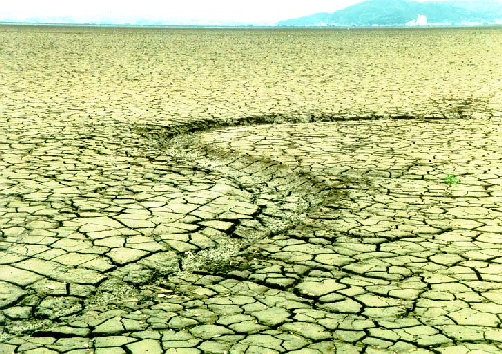

In due course a seven kilometer seawall was built to cut off the tidal flow, and in April 1997 293 giant steel shutters were lowered into place to block the aperture from the bay to the Ariake Sea. The event took place on prime time national television before a grand convocation of national and local dignitaries. Intended as a celebration of the construction state and of the human capacity to engineer, control, and exploit nature, the effect was quite contrary: the overwhelming impression was of the sea being “guillotined.” The country watched horror-stricken as death and devastation spread over the bay.

The area that lay exposed by the departing sea slowly turned into a cracked, spongy, wasteland, sprouting a ragged coat of vegetation, while the rest of the site became covered with stagnant, murky water, and the air filled with the smell of dying fish, oysters, clams, cockles and crabs. The bay was beset thereafter by chronic “red tides” of phytoplankton caused by the excess of nutrients. Many fishermen took other jobs, mostly in construction, even as workers on the actual Isahaya site. Ironically, almost at a stroke, the guillotine wielded by the national government seemed to have wiped out stocks of Japan’s best sushi ingredients: the laver (nori) yield, once a quarter of Japan’s total, collapsed, and the harvest of clams and cockles (especially the bivalve asari, hamaguri, agemaki and tairagi) sank precipitously. Local catches of striped mullet, white croaker, sea bass and other in-shore fish plunged to “around 20 percent of their peak years.” Fishermen believed that it was not only the closure but the periodic opening of the sluice gates to flush out polluted waters that was having ruinous effects.

The philosopher, Umehara Takeshi, saw a profound symbolic meaning in the Isahaya reclamation. For him, what Isahaya manifested was nothing less than the emptiness of the postwar Japanese soul: “believing in no religion, valuing no morality, carelessly killing living things for profit, and feeling no sense of sin.” Yet the bureaucratic enthusiasm was undimmed. Nagasaki Governor Takeda Isamu spoke of the project ensuring “a bright future for Japanese agriculture in the coming century” – surely a preposterous view of the salty, sodden, and inferior lands that were being created at fabulous public expense – and Fujinami Takao, Minister of Agriculture (who bore the primary responsibility for the decision), remarked that “the current ecosystem may disappear, but nature will create another one.” The insight of the fishermen, that to cut off the sea’s womb was to cause sterility, contrasted sharply with the bureaucratic view that one ecology was the equal of another.

Not only the usefulness but the safety of the works was also at issue. The construction was carried out on a base of a clay soil which one expert described as “the worst possible foundation, not only in Japan but on a global scale as well,” likely to disintegrate under pressure. The foundations of the dykes and sea wall sank steadily, and the project has been described as rather like building a fortress on yogurt. To make matters worse, the entire district is within an earthquake zone, subject to regular tremors, and in the past has been the scene of vast catastrophes such as in 1792 when an eruption of the adjacent Mt. Unzen was accompanied by an earthquake and tidal wave that killed around 15,000 people. The Ministry of Agriculture had evidently not taken such contingencies into account in its design and construction works.

The symbiotic cycle they so rudely disrupted was delicate. Japan’s wetlands, especially tidal and estuarine wetlands, in their natural state, had economic value not only for the food and raw materials regularly taken from them but for the complex of functions best described as “ecological services”: water regulation, nutrient recycling, waste treatment, disturbance regulation and erosion control, not to mention recreation and leisure. The internationally accepted calculation of the economic value of such tidal flats puts it at a minimum of $US22, 832 per hectare per year, a figure likely to rise as, or if, natural capital and ecosystem services become more stressed and more scarce in future. Addressing only one of these “ecological services,” waste recycling, the economic value of the Isahaya wetlands in their natural state would seem to be greater than the total cost of the works, because of its capacity to break down the sewage of 300,000 people. The state was therefore responsible not only for pouring huge amounts of public funds into a project to develop useless land and polluted water, thereby plunging a regional ecology into crisis, but also for destroying a major public asset. The Saga court judgment suggested that it was time to settle these long-overdue accounts.

The obvious question is why did people allow such a plainly misguided, unnecessary and damaging project. Why did they not simply vote those responsible out of office? In theory they might have, but in practice the network of “private” interests served by “public” works was too finely woven and intricate. First of all, the usual rule in public works is that approximately two-thirds of the costs are met by national government and one-third by prefectural and local authorities, but Isahaya being a special case the proportion was set at 82:18. In other words, local communities got the works at minimal cost, whether they wanted them or not and national taxpayers footed the bill, likewise without ever exercising any political or environmental judgment. For the former, short-term economic advantage was served by saying yes, while for the latter the price only slowly dawned on people as they were told of the bankruptcy the country faced and their pension and welfare systems were declared insolvent.

Secondly, also typical of public works projects throughout the country, this project has long been embedded in a network of bureaucratic-construction industry-political collusion. Nearly 90 per cent of 654 public works contracts related to the Isahaya works between 1996 and 2000 were allocated at administrative discretion without competitive bidding. More than 400 former officials from either the national agriculture ministry or the prefectural government were employed in the 61 companies involved in the works. The Nagasaki prefectural branch of the (ruling) Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) depends heavily on political funds donated by firms benefiting from works contracts and the interests of many local people are involved, some as sub-contractors and some as laborers. Local fishing cooperatives are also paid substantial sums, nominally for “research into fisheries” but plainly intended to buy their silence. Such a network of economic and political interest has always been stronger than any fishing net. One critic coined the term “reclamation fascism” to try to describe it.

Initially, all that had been required under the Public Water Reclamation Law was a perfunctory review, carried out in 1986 by the Environment Agency, which simply referred to materials provided by the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries without being able to contest their accuracy or to conduct independent experiments or investigation. Its conclusion, that the impact on Isahaya Bay and its marine surrounds would be “within acceptable limits” remained thereafter the crux of the bureaucratic justification for the project. Faced with a growing local sense of disaster over the collapse of the laver and shellfish harvests, however, in 2001 the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries commissioned a “reassessment.” This new review committee in due course came to the feeble conclusion that the works could proceed but should be reconsidered (minaoshi) in the spirit of “serious and deeper concern for the environment.” It recommended that the reservoir gates be opened, on short, medium and long-term basis, to investigate the project’s environmental impact on tide flows and water quality. Yatsu Yoshio, Minister for Agriculture and Fisheries in the Mori government, promised “maximum respect” to the committee’s findings and in April of the following year the gates were indeed opened for about a month for a short-term impact survey.

The more contentious matter of medium and long-term opening, which had obvious implications for the completion of the project as a while, however, was merely referred to as a new “specialists” committee. In December 2003, that committee (made up of seven ex-bureaucrats, including several major proponents of the project from the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries) came to the expected conclusion that to implement this recommendation would cause delay on the project (by then already 94 per cent complete), and would therefore be too “technically difficult.” In other words, it would cost time and money, and negative findings might even threaten the completion of the project as a whole. In May 2004, the then Minister (Kamei Yoshiyuki) announced the decision to “set aside” the medium and long-term impact studies. Instead he chose a technical, engineering “fix:” the dredging of the seabed and insertion of large quantities of sand and steps to improve the quality of the reservoir water. This was essentially the prescription of the “Ariake Sea and Yatsushiro Sea Special Measures Law” adopted in 2002: new sewage treatment plants, dredging and clearing works, the planting of trees and reed beds, and the promotion of fish and technology for the development of marine resources. It was a characteristically capital intensive, bureaucratic, technological fix for an ecological problem caused by bureaucratic irresponsibility, if not criminality.

It seems unlikely that such piddling measures would stop the spreading ecological crisis or bring the former “Sea of Fertility” back to life. The best independent scientific opinion, as presented by a committee of leading academic specialists, was that such steps would treat the symptoms, not the disease, and that the basic problems of the Ariake Sea would continue, and likely worsen. The bureaucratic bottom line was that there could be no turning back, the works must go on.

The Liberal Democratic Party, faced in the 1990s with growing protest against its public works programs, abandoned a small number of projects, cut the public works budget, and adopted “nature regeneration” as a major slogan. Most dramatic of the cancellations was that of the reclamation and desalination project at Lake Nakaumi on the borders of Tottori and Shimane prefectures. The Nakaumi works, designed to create both land (2,540 hectares) and water (desalination of the lake to create 2.7 billion cubic meters of fresh water) had been underway for nearly 40 years, with periodic suspensions because of the protest, and were also almost complete when the decision to abandon them was finally taken in 2002. It differed from Isahaya in that the “flood prevention” justification did not apply, and the opposition from the surrounding communities was united. It seems likely that the authorities in Tokyo decided to draw a line between the two projects and to insist on completion of Isahaya.

Despite the Nakaumi cancellation, and the suspension of wetland reclamation projects in Nagoya and Chiba, other major dam and reclamation projects were given the go-ahead. Overall, the reforms were more cosmetic rather than surgical. In 2001, Prime Minister Koizumi gained widespread national support and became an extraordinarily popular Prime Minister because of his pledge to reform Japan even if it meant having to destroy his own party to do so. After more than three years, however, his slogans rang hollow. His record was of the consistent defense of established bureaucratic, irresponsible, and environmentally devastating policies of the construction state. The challenge he faced was that the doken kokka was the virtual alter ego of his party. Under him, the bureaucracy seems to have concluded that, while sacrificing Nakaumi, it would otherwise not be necessary to stop, let alone reverse, any of its major projects. LDP-led governments continued to worship the sacred cow of construction, despite the rising mountains of public debt and despite the slowly growing realization that Japan’s severely functionalist, riverine, coastal, and wetlands engineering was out of step with best practice around the world. In Holland, Italy, the US, and South Korea, a fundamental rethinking is underway on the centuries-old policy on reclamation. Holland, with its long experience, has decided to phase out all further reclamation, return sectors of reclaimed land to tidelands and wetlands, and leave its sea sluice gates open save at times of storms and extra high tides. Italy moves to reverse its long commitment to wetlands reclamation by restoring the Po Delta region. The US has begun to restore reclaimed lands in the San Francisco Bay area to wetlands. South Korea, which only belatedly signed the Ramsar Convention in 1997, promptly passed a Wetlands Protection Law and canceled the mammoth Lake Sihwa tidelands reclamation project in the vicinity of Ansan City south of Seoul, one similar in character to Isahaya but almost six times greater in scale. It seemed to be moving to rethink significant elements of its approach to “modernization,” and in doing so to challenge the “Japanese” model.

The pattern at Isahaya – of decision-making without consultation, extravagant use of public monies to buy consent, and resolute pressure against dissenters or opponents – is the same as in other villages and towns designated as sites for dams, nuclear reactors, garbage disposal plants, and in some cases airports. The continuation of the Isahaya project demonstrates that grand design without limit for transforming the Japanese archipelago, drawn up in the early 1970s and best known in Tanaka Kakuei’s formulation of “Rebuilding the Japanese Archipelago,” still informs the bureaucratic mentality. Rivers, coast, wetlands, mountains and forests, continue to be sacrificed to feed the engine of growth.

In 2006, the works are scheduled for completion. The flow of contracts, jobs, subsidies, and bribes will cease and the permanence of the damage being done to the Ariake Sea and its environs will have to be faced. Saga District Court Judge Enoshita is asking must the country wait for this to happen. By directly contradicting the government of the day he asks his countrymen to confront the fundamental question of the meaning of life: what purpose do the Japanese people collectively wish to serve in the 21st century? Late 20th century Japan found such meaning in GDP growth at all costs, a consensus first moulded by the bureaucracy and then vigorously pursued under its direction. Isahaya, and other sites, now confront bureaucrats and citizens alike with the stark implications of that choice. The national consensus appears to be slowly shifting in favour of sustainability, accommodation with and respect for nature, and the recognition of human limits, but the adjustment in institutions and policies has still a long way to go. The Isahaya judgment is an important milestone.

Gavan McCormack wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted December 17, 2005.

Gavan McCormack, Australian National University and International Christian University, Tokyo, is a Japan Focus coordinator. His most recent writing has been about North Korea (Target North Korea, Nation Books 2004), but he here returns to his longstanding interest in the Japanese public works political economy, elaborated previously in The Emptiness of Japanese Affluence (ME Sharpe, 2nd edition, 2001. email: [email protected]