Charter 08 Framer Liu Xiaobo Awarded Nobel Peace Prize. The Troubled History and Future of Chinese Liberalism

Feng Chongyi

Introduction

Liu Xiaobo, the primary drafter of Charter 08, has just been awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for 2010 for “his long and non-violent struggle for fundamental human rights in China.” The award signals international recognition of the Chinese people’s quest for justice, universal human rights and democracy through peaceful means.

China is a rare example of a Leninist party-state that wields power in the wake of the collapse of communism and the Soviet Union in the late twentieth century. Its remarkable economic growth for three decades has triggered enthusiasm home and abroad for the “Beijing Consensus” or the “Chinese Model”, a loose conceptualization of the Chinese experience in achieving economic growth, capitalist development, rapid urbanization and social change at the expense of human rights. Contrary to the view that human rights and social justice are dispensable in order to achieve economic efficiency and create wealth, contemporary Chinese society shows signs of deep striving for human rights, constitutional democracy, social justice and equitable distribution. These values are clearly articulated in the monumental document Charter 08 and powerfully exemplified in recent waves of social protest.

The publication of Charter 08 in China at the end of 2008 was a major event generating headlines all over the world. It was widely recognized as the Chinese human rights manifesto and a landmark document in China’s quest for democracy. However, if Charter 08 was a clarion call for the new march to democracy in China, its political impact has been disappointing. Its primary drafter Liu Xiaobo, after being kept in police custody over one year, was sentenced on Christmas Day of 2009 to 11 years in prison for the “the crime of inciting subversion of state power”, nor has the Chinese communist party-state taken a single step toward democratisation or improving human rights during the year.1 This article offers a preliminary assessment of Charter 08, with special attention to its connection with liberal forces in China.

Liu Xiaobo

The Origins of Charter 08 and the Crystallisation of Liberal and Democratic Ideas in China

Charter 08 was not a bolt from the blue but the result of careful deliberation and theoretical debate, especially the discourse on liberalism since the late 1990s. In its timing, Charter 08 anticipated that major political change would take place in China in 2009 in light of a number of important anniversaries. These included the 20th anniversary of the June 4th crackdown, the 50th anniversary of the exile of the Dalai Lama, the 60th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Republic of China, and the 90th anniversary of the May 4th Movement. Actually Chinese liberal intellectuals had earlier begun to advocate and discuss a road map and timetable for the march to constitutional democracy.2 Charter 08 was discussed from the second half of 2008. Its three primary initiators and drafters were leading dissidents Liu Xiaobo, Zhang Zuhua and Jiang Qisheng.

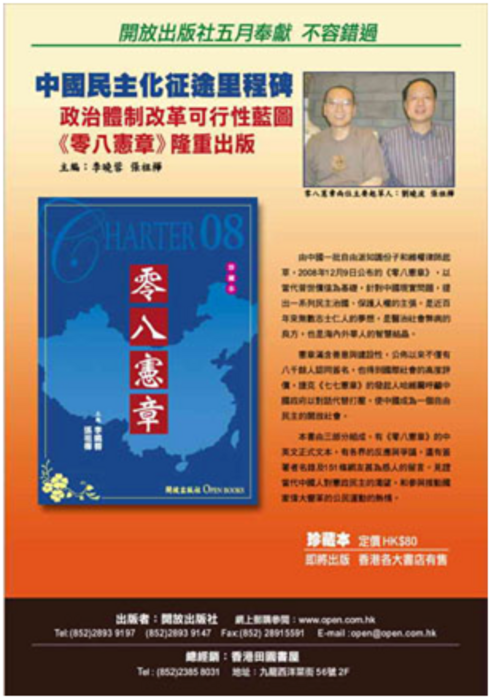

The front cover of edited volume Charter 08. Liu Xiaobo (left) and Zhang Zuhua, two primary drafters of the Charter.

Liu Xiaobo, born in 1955, joined the faculty at Beijing Normal University in 1984 and received a PhD in literature there in 1988. He was one of the four celebrated intellectuals who took part in the student hunger strike at Tiananmen Square in 1989 and played a key role in mediating between the students and the troops for the peaceful withdrawal of students from the square. Nevertheless, he was jailed after the June 4th Tiananmen Massacre and subsequently lost his job. Liu became a freelance writer, political commentator and human rights activist, and served as President of the Independent Chinese Pen Center3 for the period of 2003-2007. Liu was repeatedly arrested and detained by Chinese authorities for criticizing the ruling Chinese Communist Party and promoting democracy and human rights. Zhang Zuhua, born 1955, received a BA in political science from Nanchong Normal University in 1982 and was a member of the Communist Youth League Standing Committee in charge of Youth League affairs of the CCP Central Committee and the State Council in 1989 when the Tiananmen Massacre took place. He lost his position for supporting the democracy movement and became a self-employed researcher with a focus on Chinese civil society. He has published extensively on political reform in China and was briefly detained by the police in 2004 for his dissenting political views. Jiang Qisheng was born in 1948 and was a leader of the Tiananmen student movement in 1989 when he was a PhD candidate in Philosophy at People’s University in Beijing. His PhD candidacy was terminated and he was imprisoned twice, for about two years between 1989 and1991 for participation in the student movement and four years during the period 1999 to 2003 for distributing pamphlets to commemorate the Tiananmen movement. To avoid crackdown by the security apparatus, the draft Charter was hand delivered to a small circle in Beijing for comments and revision, although it was sent as an email attachment for signatures once it was finalized. To avoid the accusation of “colluding with hostile forces abroad”, Chinese overseas were deliberately excluded from the original signatories. After acquiring 303 signatories nationwide, the organizers planned to release Charter 08 on 10 December 2008 in commemoration of the 60th Anniversary of the Universal Declaration Human Rights by the United Nations. However, it was released on the Internet one day earlier as Liu Xiaobo and Zhang Zuhua were detained on 8 December 2008 because of their association with the document.

Charter 08 takes its name from Charter 77 written by intellectuals and activists in the former Czechoslovakia and borrows ideas and language from several international documents on human rights and democracy, including the Constitution of the United States, the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen, the Universal Declaration Human Rights of the United Nations, and the reconciliatory approach of South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, as well as relevant Chinese documents throughout the modern era, including the Constitution of the People’s Republic of China.

Vaclav Havel (right) and other Charter 77 signatories address demonstrators in Prague on December 10, 1988, to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Universal Declarations of the Human Rights.

Charter 08 is a wide-ranging and comprehensive political reform program that embraces human rights, constitutional democracy and social policies for distributive justice.4 Part one is a “preamble”, providing an overview of the Chinese democracy movement over the last century, identifying fundamental problems of current communist rule in China, urging the regime to “embrace universal human values, join the mainstream of civilized nations, and build a democratic system”. Part two lays down five “fundamental concepts” of freedom, human rights, equality, republicanism, democracy and constitutional rule as fundamental principles and defines these concepts according to the tenets of liberal democracy. Part three offers nineteen specific recommendations calling for amending the constitution, separation and balance of powers, democratizing the lawmaking process, judicial independence, nonpartisan control of public institutions, protection of human rights, election of public officials, urban-rural equality, freedom of association, freedom of assembly, freedom of expression, freedom of religion, citizen education, protection of property, fiscal reform, social security, environmental protection, a federal republic, and transitional justice (seeking social reconciliation on the basis of the findings of a Truth Investigation Commission investigating the facts and responsibilities of past atrocities and injustices). Part four is a short “conclusion” about China’s responsibility to humankind, appealing to all Chinese citizens to participate in the democratic movement and echoing the call in the preamble that human rights and democracy are vital for China as a major country of the world, as one of five permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, and as a member of the UN Council on Human Rights. Charter 08 categorically sets constitutional democracy as the goal for Chinese political development and peaceful reform as the means to achieve that goal.

The concepts, standpoints and recommendations elaborated in Charter 08 represent a remarkable progress in sophistication of liberal and democratic ideas in China since the 1989 democracy movement symbolised by the hunger strike at Tiananmen Square and demonstrations on the streets of Beijing and other major cities. The connection between the two events is obvious, as all three primary drafters and many of the signatories took part in the democracy movement in 1989. For all of its significance, impact and extraordinary level of social mobilisation, the 1989 democracy movement produced no comprehensive document of political demands and aspirations, not even unified slogans for political change and democracy. This limitation was not due to negligence on the part of the democracy movement leaders and activists, but reflected the reality that even they had not understood core concepts of democracy and human rights.

May 15, 1989, Tiananmen the day after the hunger strike was proclaimed

Charter 08 represents a significant step forward and provides a remedy for the limits of the 1989 democracy movement. Despite harsh suppression of democracy and liberal ideas by the Chinese party-state, and partly due to this suppression, liberalism and the quest for human rights have been on the rise and achieved a level of sophistication in China since the late 1990s. Charter 08 can be seen as an embodiment and synthesis of theoretical and intellectual achievements by Chinese liberal intellectuals over a decade. The first achievement is the open embrace of constitutional democracy in rejection of one-party dictatorship, including the illusion of “socialist democracy” or “proletarian democracy”. For those who are critical of the practice of constitutional democracy or liberal democracy in the West, the universal values, liberal concepts and democratic recommendation summarized in Charter 08 are nothing but common sense. However, as argued by the signatories of Charter 08, one-party dictatorship is the root of social ills and inequality in China, whereas constitutional democracy or liberal democracy, less than perfect as it is, forms the basic institutional framework that is the prerequisite for other improvements, including deliberative democracy, social justice and economic equality. This is a lesson that has been paid for in the blood of millions living under state socialism.

We know that Chinese “liberal elements” in the 1980s, including the most profound thinkers such as Wang Ruoshui, Su Shaozhi and Yan Jiaqi, even the most radical dissidents such as Wei Jingsheng, were confined to the Marxist framework in their quest for democracy, typically expressed as “socialist democracy and legality”. This limit was overcome by Chinese liberals by the late 1990s, when Li Shenzhi, a senior communist expert on international affairs and former vice-president of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences with the rank of vice-minister, solemnly proclaimed that:

After three hundred years of comparison and selection in the whole world since the age of industrialization, and particularly after more than one hundred years of Chinese experimentation, the largest in scale in human history, there is sufficient evidence to prove that liberalism is the best, universal value. Today’s revival of the liberal tradition stemming from Beijing University will beyond doubt guarantee the emergence of a liberal China in the world of globalization.5

The conversion to liberalism also means that Chinese liberals are no longer confined to formulations of “socialist democracy” that guarantee the leading role of the CCP. The experience of the June 4 crackdown and the collapse of communism in the former Soviet Union and eastern Europe provided an opportunity for Chinese liberals to deeply reflect on the illusion of “socialist democracy”, and they were awakened to the fact that the party-state had long been deceiving itself and others in claiming communist one party rule as a higher form of “democracy”. They sharply pointed out that the CCP under Mao’s leadership overthrew the Nationalist dictatorship only to supplant it with the CCP dictatorship, and Mao’s successors, the post-Tiananmen leadership, has maintained the despotic system and become yet more corrupt. Since the 1990s, based on their new found conviction that one party dictatorship and democracy are not compatible, Chinese liberals have categorically abandoned one party rule for constitutional democracy with all of its inherent features such as multi-party elections, legal safeguard of human rights by limiting the power of the government, and checks and balance of powers among legislative, executive and judicial branches.6

Front cover of monthly journal Charter 08.

The second achievement is to address the issues of social justice from a liberal perspective based on an “overlapping consensus” between liberalism and social democracy. The Chinese new left has labelled Chinese liberals “neo-liberals”, resulting in grave confusion and misunderstanding.7 Even some China scholars in the West assume as a matter of course that the Chinese new left champions the cause of social justice, which is neglected by Chinese liberals. However, in the context of the contemporary West, neo-liberals are widely regarded as a right wing political and intellectual force prioritising efficiency over equality and promoting market mechanisms at the expense of the welfare state. Contemporary Chinese liberals differ fundamentally from “neo-liberals” in the West. They understand liberalism in the classical sense as a political philosophy that considers individual liberty as the most important political goal and upholds liberal principles such as legal protection of individual rights, the rule of law and limitations on state power. They not only strive for individual freedoms and seek to replace the despotism of the Leninist party-state with liberal democracy, but many also fight in the forefront against social inequality and seek to champion the cause of the working class quest for equality and a better life. Three out of nineteen specific recommendations in Charter 08 are devoted to the issues of social inequality, including the demands to strictly protect peasant land rights (recommendation 14), build a social security system that covers all citizens (recommendation 16) and repeal the current urban-rural household registration system and implement equal rights for all citizens.8 Chinese liberals are tackling the burning issues in China, including increasing social inequality. Apart from promoting market efficiency, liberty, democracy and the rule of law, they also took pains to advocate social justice, well before the new left took up the issue; apart from promoting equality of opportunity and procedural justice, they also stand for distributive justice.9 In the eyes of liberals, without accompanying processes of democratizing political power, China’s reform has been distorted by the power elite and turned into a process of “stealing what is entrusted to their care” (jianshou zi dao) and “taking all the food by those in charge of cooking” (zhangshao zhe si zhan daguofan).10 As summarised by Xu Youyu, “most liberals do not promote the market at the expense of justice. What they have consistently advocated are as follows: 1) resolutely support markets economy as a mechanism to prevent plunder by power; 2) expose the grave injustices resulting from the current reform and demand further reform to eliminate abuses of power; 3) take political reform as the fundamental solution and the top priority”.11 As a matter of fact, the social democratic elements within the liberal camp in particular have strongly supported the egalitarian implications of the welfare state.

In tackling the issues of equity and inequality, Chinese liberals differ from both the Chinese old and new left in two fundamental ways. Firstly, liberals see the despotic political system, as well as the marketisation of political power in the process of transition to the market economy (rather than the market economy per se), as the primary source of inequality, including the unequal distribution of wealth. Based on the observation that power holders have abused their power in the course of presiding over “yuanshi jilei” (original accumulation), Chinese liberals draw the conclusion that unfair distribution in China today is not primarily manifested in the distribution of national income in the form of wages and property, but in the allocation and control of resources through political power.12

“Current social evils in China”, argues leading liberal Zhu Xueqin, “cannot be simplified and equated with a ‘western disease’ and a ‘market disease’. They are a ‘Chinese disease’ and a ‘power disease’ resulting from the peculiar circumstances where the market mechanism is parasitical, distorted, and even suppressed by an outmoded power mechanism. Liberals raised the issue of social justice earlier than the new left did, and they dug deeper to the root of the problem, pointing out that it already existed in the Mao era, as in the plunder of private property, possession of public property and suppression of different political views by the privileged stratum. These social injustices took shape from the inception of that system, but were concealed by Mao’s illusory egalitarianism. The power mechanism has not changed with the introduction of the market mechanism but has increased its privileges and augmented the scope of rent seeking. Hence there is structural corruption and unprecedentedly acute social injustice in our society.13 Qin Hui also argues that the secret of China’s current economic advance is its low human rights standards, a salient feature of “power elite capitalism” (quangui zibenzhuyi). China has become an investor’s paradise because the prices of the four prime factors of production (human capital, land, credits and non-renewable resources) have been kept artificially low by reducing the bargaining power of providers through political suppression.14

Secondly, instead of waging an all-out war against the market, capitalism and the “middle class” as the left did, the liberals firmly defend the market and the “middle class” while focusing their attacks on the unjust power structure presided over by the party-state, including the “power elite” (quangui) and the “upstarts” (baofahu) who are “getting rich ahead of others” (xian fu qilai) through the abuse of political power in one way or another. It is the belief of Chinese liberals that universal protection of rights, including property rights, is the foundation of social justice. Xu Youyu points out that “the new left picks up other people’s phrases to attack marketisation, ignoring the positive effect of marketisation in breaking down the oppressive old system”. According to Xu, as equal rights forms the necessary condition for economic and social equality, what should be done is to protect the interests of working people against “bigwig privatisation” (quangui siyouhua) through the creation of a just legal framework to regulate the market and human behaviour.15

Qin Hui points out that since social injustice in China today is rooted in an unfair process of competition where some abuse political power to create and accumulate wealth while others lose out, “what is important is that there should be a simultaneous process of taking away both the constraints and protections of the old system, avoiding thereby the consequences in which some people continue to enjoy protection after taking away the constraints and others continue to suffer from the constraints after losing the protection, that the opportunities are monopolised by the former whereas the risks are taken by the latter, and that the former take the ‘fruits’ whereas the latter pay the price”.16

The third achievement of Chinese liberalism since the 1990s is a sound understanding of the rule of law. Unprecedented in Chinese history, a clear distinction has been made first by liberal intellectuals and then by the government and the public in general between rule by law (law as a tool for the rulers) and rule of law (rulers subject to and limited by the law).17 Inspired by the liberal discourse on human rights and the rule of law, citizens with growing rights consciousness have become increasingly assertive in using the constitution and other laws to protect their rights. Since 2003 there has been a powerful and comprehensive rights defence movement (weiquan yundong) involving all social strata and covering every aspect of human rights, ranging from protests by villagers against forced seizures of farmland by the government and developers to strikes by workers against low pay and poor working conditions, from campaigns by ex-servicemen for unpaid social entitlements to protests by affected residents against environmental pollution, from campaigns by petitioners for redressing injustice to campaigns by journalists for a free press, and from campaigns by Falun Gong practitioners for the freedom of belief to campaigns by the Christian family churches for the freedom of assembly.18

Signatories of Charter 08: Rallying the Liberal Camp

To a great extent, signatories of Charter 08 can be seen as the apotheosis of the Chinese liberal camp. In term of professional and social diversity, the 303 original signatories of Charter identified themselves as scholars of all disciplines, lawyers, writers, journalists, editors, teachers, artists, officials, public servants, engineers, businessmen, workers, peasants, democracy activists and rights activists. In political or ideological perspective, they are liberal leaders in all walks of life.

China’s “reform era” can be divided into two different phases punctuated by the June 4 massacre of 1989, which brought a premature end to the healthy trend of political liberalisation inspired by democratic aspiration. Following the massacre, and in the wake of the collapse of communism in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, the CCP led by Deng Xiaoping took two resolute measures for survival: a ruthless purge of democratic forces in society and within the CCP on the one hand and accelerated introduction of “market economy” on the other. With the aid of capital, technology and consumer markets, facilitated by globalisation, China rapidly evolved into a new order of market Leninism, a useful term coined by New York Times correspondent Nicholas Kristof in which the Leninist party-state is sustained by the combination of relatively free-market economics and autocratic one-party rule.19 In other words, it is an astonishing paradox, putting together previously incompatible elements of both capitalism and communism, the latter of which by definition aims at eliminating capitalism. To the surprise of many throughout the world, this strange hybrid has produced an economic dynamism parasitic on the exceptionally low cost of productive factors, the expanding global market and the expansion of imported and indigenous technologies and expertise. The enormous wealth generated by this new prosperity has provided greater incentive for Chinese communist power holders to hang on to power and more resources to co-opt other social groups and repress the opposition. The result is a transition to and consolidation of “power elite capitalism (quangui zibenzhuyi)”, in which the capitalism is dominated by the communist bureaucracy, leading to rapid, sustained economic growth on the one hand and endemic corruption, striking social inequalities, ecological degeneration and political repression on the other. This unexpected outcome has disheartened many democracy supporters who fear that China’s transition is “trapped” in a “resilient authoritarianism” which could be maintained for the foreseeable future.20

However, because it has produced both acute social tensions beyond management and the new social and political forces challenging the one-party dictatorship, market Leninism’s resilience may prove to be limited, especially when facing concurrent economic downturn and deep social unrest. The social tensions have led to an amorphous but increasingly powerful wave of “rights defence movements” mentioned above. The most promising new political force engendered by market Leninism in China is the formation of a liberal camp in the late 1990s, consisting of at least six distinctive but partially overlapping categories: liberal intellectuals, democracy movement activists, liberals within the CCP, Christian liberals, human rights lawyers and grassroots rights activists.21 Each of these groups propounded liberalism from its own perspectives through publications and speeches, took part in a variety of social and political activities for the cause of democracy, sometimes expressed mutual support for one another when persecuted by the party-state, and occasionally joined in issuing joint petitions or open letters on the internet to express their shared concerns or demands for democratic changes.

Liberal intellectuals

The majority of intellectuals in China today are at least prone to liberalism in the sense that they share beliefs in market economy, individual rights, criticism of state monopoly power, and, to a lesser extent, liberal democracy, although few dare to actively confront the party-state and put their beliefs into practice.22 Chinese liberals have proclaimed a “rebirth” or “resurfacing” of liberalism since the late 1990s, beginning with 1998, a decade after the Tiananmen crackdown.23 Several factors contributed to this development of liberalism, including the expectation for change after Deng Xiaoping’s death, the belief that the Asian financial crisis was rooted in authoritarianism, the perception of further reforms necessitated by economic development, the provocative attacks on liberalism by the new left, growing awareness of the accelerating pace of globalisation, and the posture of Jiang Zemin’s leadership with respects to human rights and the rule of law, as shown by the political report of the Fifteenth Party Congress and the signing of the “International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights” and the “International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.”24

The core of the emerging liberal camp is a group of mainly middle aged scholars and intellectuals who can be broadly identified as members of the “Cultural Revolution Generation”, such as Zhu Xueqin, Xu Youyu, Qin Hui, He Weifang, Liu Junning, Zhang Boshu, Sun Liping, Zhou Qiren, Wang Dingding and Zhang Weiying. Their liberalism is rooted in their own political experience as well as their exposure to liberal theories. While their experience in and reflections on totalitarian rule during the Cultural Revolution provided strong stimuli to search for a new political belief, in the 1970s they were intoxicated with various brands of humanism and since the 1980s they were attracted to both Western and modern Chinese liberal traditions. They published their ideas in monographs, theoretical journals, such as Dong Fang (Orient) and Kaifang Shidai (Open Times), and newspapers, such as Nanfang Zhoumo (Southern Weekends) and Nanfang Dushibao (Southern Metropolitan Daily), and, more freely, on the internet. The party-state has prevented them from forming an organisation for their political endeavour, but they manage to gather regularly on informal occasions and at conferences organised by colleagues.25

Gathering of Chinese liberal intellectuals for a conference on Chinese liberalism, Sydney, January 2003. First row from the left: Xie Yong, Xu Youyu, Zhu Xueqin, Jean-Philippe Beja (guest discussant), Qin Hui, and Gao Hua. Second row from the left: Qiu Queshou, He Yihui, Feng Chongyi, Xiao Gongqin, Wu Guoguang, You Ji (guest discussant), Ren Jiantao, and Xiao Bin.

Zhu Xueqin, born 1952, is a leading historian and public intellectual based at Shanghai University. He established his belief in liberalism through a thorough examination of the French Enlightenment in his PhD thesis and became a major exponent of contemporary Chinese liberalism.26 Xu Youyu, born 1947, is a philosopher and public intellectual based at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Apart from promotion of liberalism, Xu is also an expert on Western social theories including Marxism and the Frankfurt School and a well-known historian of the Cultural Revolution.27 Qin Hui, born 1953, is a historian and public intellectual based at Qinghua University. Within the liberal camp, Qin stands out particularly for his preferences for privatisation under strict conditions of democratic openness, and the primacy of social justice and institutions of social democracy.28 He Weifang, born 1960, is a law professor and public intellectual based at Beijing University, striving for judicial independence and modernisation of the Chinese judicial system in accordance with the principles of the rule of law.29 Liu Junning, born 1961, is a political scientist and public intellectual currently based at the Institute of Chinese Culture after his dismissal from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences due to his expression of liberal views. Liu has played a leading role spreading the concept of constitutional government and organising several liberal journals and book series such as Gonggong Luncong (Res Publica) and Minzhu Yicong (Translated Works on Democracy).30 Zhang Boshu, born 1955, is a philosopher and public intellectual formerly based at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. Among liberal intellectuals in China today, Zhang goes farthest in directly confronting the autocracy and systematically promoting liberal-democratic alternatives.31 Sun Liping, born 1955, is a sociologist and public intellectual based at Qinghua University. Sun is well known for his criticism of the inequities in the current social system and his advocacy of transformation to an open and liberal society.32 Zhou Qiren (born 1950), Wang Dingding (born 1953) and Zhang Weiying (born 1959) are like-minded economists and public intellectuals based at Beijing University, sharing an emphasis on private property rights.33

Liberals within the CCP

Liberals within the CCP are usually known as “dangnei minzhupai” (democrats within the CCP). They are CCP members who have shifted their belief from communism to liberal democracy and have been actively striving for a democratic transition in China, although some may continue to believe in the possibility of democratic socialism.34 What distinguishes them from the former group of liberal intellectuals is primarily that they are CCP members and in some cases officials. However, liberals within the CCP usually choose to speak mainly to the top party leadership in a coded language familiar to communist officials. They also have special outlets to publish their ideas, such as Yanhuang chunqiu (Chronicles of China), Tongzhou gongjin (Advance in the Same Boat) and Zhongguo shichang jingji luntan wengao (Chinese Market Economy Forum Drafts), the journals under their control. In fact, liberals within the CCP have used their positions to create space for the discourse on liberalism and played key roles in facilitating the resurfacing of liberalism in China in the late 1990s.

Most active members of this group are retired officials including Bao Tong, former director of the Political System Reform Research Office of the CCP Central Committee and secretary of the CCP Politburo Standing Committee; Du Daozheng, director of Yanhuang chunqiu, former director of the State Press Bureau and former chief editor of Guangming Daily; Du Guang, former director of Research Office and the Librarian at the Central School of the CCP; Du Runsheng, secretary general of the Central Rural Work Department in the 1950s and head of the Rural Policies Office of the CCP Central Committee in the 1980s; He Jiadong (1923-2006), former deputy director of Workers’ Press; Hu Jiwei, former chief editor and director of the People’s Daily; Jiang Ping, former president of Chinese University of Political Science and Law; Li Rui, vice-minister of the Ministry of Water Conservancy in the 1950s and deputy chief of the Organization Department of the CCP Central Committee in the 1980s; Li Pu, former deputy director of Xinhua News Agency; Li Shenzhi (1923-2003), former deputy president of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences; Lin Mu (1927-2006), former deputy chief of the Propaganda Department of the CCP Shaanxi Provincial Committee and former Party Secretary of Northwest China University; Ren Zhongyi (1914-2005), former Party secretary of Guangdong Province; Wu Jinglian, senior research fellow at the Development Research Centre of the State Council; Xie Tao, former deputy president of China People’s University; Yang Jisheng, deputy director of Yanhuang chunqiu and former senior journalist of Xinhua News Agency and chief editor of Chinese Market; Zhao Ziyang (1919-2005), deposed General Secretary of the CCP;35 Zhong Peizhang, former director of the Theory Bureau, the Propaganda Department of the CCP Central Committee; Zhu Houze, former Party Secretary of Guizhou Province and chief of the Propaganda Department of the CCP Central Committee; and Zong Fengming, former Party Secretary of Beijing Aeronautical Engineering University.

Gathering of liberal intellectuals and liberals within the CCP for a forum on liberalism and social democracy, Beijing, December 2005. First row from the left: Zhu Houze, Feng Chongyi, Du Runsheng, Li Rui, and Zhang Sai.

Democracy movement activists

This group also shares with the liberal intellectuals a common political belief but adopts a different strategy to achieve the goal of democracy. Democracy movement activists openly challenge the ban on political organisation, form various organisations, and replace the communist government’s monopoly on power through mass movement, peacefully or otherwise, compared to liberal intellectuals who act within the legal framework and seek to persuade the CCP to reform and play a role in democratic transition. It is therefore not surprising that in 1998, while the liberal intellectuals launched an “open discourse” on liberalism and the democracy movement activists were busy organising the Zhongguo minzhudang (China Democracy Party), the two groups did not communicate with each other at all. The core leaders of the China Democracy Party are either Democracy Wall Movement veterans, such as Xu Wenli and Qin Yongmin, or former student leaders of the 1989 Tiananmen protest such as Wang Youcai and Liu Xianbin.36

However, within the group of democracy movement activists, many have softened their activist stance and moved closer to the liberal intellectuals. Veteran democracy movement leaders such as Chen Ziming and Liu Xiaobo belong to exactly the same “Cultural Revolution Generation” of liberal intellectuals and share similar experiences and intellectual sources. Although still identified as a “hostile force” by the party-state due to their involvement in the democracy movement, their publications since the 1990s have been almost identical to those of the ordinary liberal intellectuals promoting rational, peaceful and lawful approaches to advance constitutional democracy in China. After his release from prison Chen Ziming was permitted in 2004 to set up the website Gaizao yu Jianshe (Reform and Construction), with support from He Jiadong and other liberal intellectuals. He has earned wide recognition as a scholar in the Chinese academic community and has been able to publish widely on theoretical and practical issues with his real name on major public websites in China such as Tian Yi (Training & Education in China, TECN for short) and Xuanju yu Zhili (China elections) Liu Xiaobo was elected President of The Independent Chinese PEN Center in 2003 and worked to substantially expand the association among liberal intellectuals during his tenure, which continued to the time of his arrest in 2009. He has been able to develop extensive contacts with liberal intellectuals and work together in preparing many coordinated actions, including the drafting of Charter 08. Since the late 1990s, some journals published abroad, such as Beijing Zhichun (Beijing Spring) edited by Hu Ping and Guancha (Observation) edited by Chen Kuide have published regular contributions by moderate liberal intellectuals in China. For those who were originally officials or advisers serving reform leaders Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang, such as Chen Yizhi, Su Shaozhi and Yan Jiaqi, exile to the West has also provided them opportunities for reflection and further understanding of liberalism.

Christian liberals

The emergence of Christian liberals is a new phenomenon of the social and political landscape in the first decade of 21st century China.37 The journey from politics to Christianity among some Chinese democracy activists started with Yuan Zhiming, who first became well-known as one of the three authors of the influential political TV Series River Elegy aired in 1988. As a PhD candidate in philosophy at China People’s University, Yuan escaped to the United States in 1989 after the June 4 massacre and, due to profound disappointment with the failure of the Chinese democracy movement and infighting among its leaders in exile, he converted to Christianity in 1991 while a visiting scholar at Princeton University. The circulation of his 12 part VCD Why Do I Believe in Jesus Christ circulating widely in China, sent shock waves among colleagues of the Chinese democracy movement. Equally influential was the conversion of Yang Xiaokai (1948-2004), a forerunner of the Chinese democracy movement who was well known during the Cultural Revolution for his big-character poster Zhongguo xiang hechu qu (Whither China) circulated widely in 1968 when he was 19 years old. Yang earned a PhD in economics from Princeton University in 1988, became a well-known neoclassical economist at Monash University, and was twice nominated for the Nobel Prize in Economics (2002 and 2003). For his Chinese audience, Yang is particularly recognized for promoting xianzheng jingjixue (constitutional economics), championing the view that constitutional democracy provides the best framework for economic development.38

In the last few years many liberal intellectuals have converted to Christianity and some have become leaders of the rapidly expanding “family churches” (jiating jiaohui), whose membership has been estimated in the range of 50-100 millions.39 Chinese “family churches”, also known as the “Underground” Church or the “Unofficial” Church (they do not belong to a single church but operate autonomously), are assemblies of unregistered Chinese Christians independent of the Three-Self Patriotic Movement, the government-run Christian organisation.40 “Family churches” operate outside government regulation and restriction, but they are not officially outlawed.41 Their leaders and members are often harassed by Chinese authorities who regularly break up the gatherings organized by “family churches”, confiscate bibles and other property, and even demolish venues used as temporary churches and arrest church leaders,42 mainly for fear of popular mobilisation beyond government control. The rank and file members of “family churches” are originally apolitical, but government persecution and harassment have driven many into reluctant opposition, as happened to Falun Gong practitioners in the 1990s.

Gathering of Chinese liberal intellectuals and Christian liberals for a conference on prospect for constitutional democracy in China, Sydney, February 2006. First row from the left: Edmund Fung (guest discussant), Feng Chongyi, Chen Kuide, Qin Hui, He Weifang, Jin Yan, Li Dong, and Ding Dong.

Christian liberals have served in a dual capacity as liberal intellectuals and Gospel preachers.43 They have encountered mixed responses among Christians of family churches, which are characterized by internal diversity. In terms of geography and demography, family churches can be divided into two major categories, namely the rural family churches as the main stay and the emerging urban family churches, with the former populated by villagers and the latter by young, educated urban Christians. In terms of organizational structure, these churches can be divided into the centralized hierarchical model, popular in the rural areas in inland provinces such as Henan, Anhui and Shanxi before the 1990s, and the decentralized federal model, prevalent in big cities and rural areas in coastal provinces such as Zhejiang Jiangsu and Fujian.44 Members of urban family churches, predominantly university students and young professionals and business people who have received higher education, are closer to Christian liberals. As stated by family church trainer Zheng Muxing in an interview, these members are open-minded and versed in law, sociology and other social sciences. They are attracted to the modern political system based on the core values of human rights, tolerance and universal fraternity.45 To a lesser extent, other members are fellow travellers of Christian liberals too, particularly in their common struggle for autonomy, freedom of belief, freedom of association, freedom of speech and freedom of press. However, most members and pastors of family churches prioritize autonomy and independence of the churches and maintain a distance from democracy activists who are perceived to use churches as a political tool. According to family church trainer Yu Tianyuan, separation between politics and religion is a fundamental principle of genuine Christians who oppose the use of churches for political purposes.46

Leading Christian liberals are converting Chinese family churches and bringing them toward liberalism, in both internal governance and external relations. As believers in the liberal principle of separating politics from religion, they are fully aware of the tension and dilemma between striving for the legal status and independence of the family churches on the one hand and maintaining the neutral position of the churches on the other, a dilemma rooted in the Chinese communist regime which does not tolerate religious independence and regards religion as a united front tool of the party state. The strategy adopted by Christian liberals to overcome this dilemma is to “defend rights according to the law” (yifa weiquan), promoting the rule of law and establishing a new relationship with the government within a legal framework and seeking change through legal channels, rather than rebelling against the government. Yu Tianyuan argues that, according to both Christian creed and Chinese law, a responsible Chinese citizen can act as both a good Christian and a rights activist at the same time, because Christians have the right and duty to defend the integrity of their beliefs and human rights of other citizens.47 By involvement in or providing leadership for rights defence movements, Christian liberals are exercising their constitutional rights and performing their duties as Christians and citizens, but they are not responsible for politicizing Christianity in China. “Under a tolerant social environment”, wrote a Chinese scholar, “the churches show their social concerns in cultural development, social service and charity. . . . The social concerns of the churches focus on rights defence and other political aspects in the environment in which the churches are not legalized”.48

It is precisely the strategy to “defend rights according to the law” that has become a rallying point and transformative force of Chinese Christian churches. At the outset, Christian family churches in China were characterized by underground activities, hierarchical structure and personal cult, similar to secret societies in traditional China. Under the leadership of Christian liberals, struggle for legal status and independence of family churches have become an essential part of the broad rights defence movement characterized by openness, peace and rationality. Christian churches in China today openly organize worship service, training and other activities; establish federal structures and elect their leaders through democratic processes.49 The decisions to maintain independence from the government and not register as subsidiaries of the “Three-self Patriotic Movement Committee” are also achieved through debates and democratic processes. The consensus among leaders of family churches is that these churches should not directly participate in politics but play a role as an indirect driving force in democratic transition, providing spiritual resources and preparing qualified citizens.50 Fan Yafeng even believes that if the party-state cannot take down the family churches in the current round of suppression, “a big opening will be made for China’s democratization and Christianization, and religious freedom will become a pioneer of Chinese freedoms”.51

Human rights lawyers

Known as “weiquan lüshi” (rights defence lawyers), these liberals use the courts to fight for justice, the rule of law and constitutional democracy. Rights lawyers have not only rigorously defended various victims whose rights were abused by the party-state or corporations, but also played a role as opinion leaders in linking rights defence cases with political aspirations for the rule of law and constitutional democracy. Apart from representing clients in ordinary cases, they take up politically sensitive cases involving victims of state power, defend political and civil rights in cases of wide social and political significance, and provide legal aid for individual and collective rights defence actions. Some have also played important roles as legal activists and opinion leaders. They publish regularly on “sensitive topics” via the Internet and other media outlets, organise or participate in Political petitions, and consciously use lawsuits as social mobilisation linking rights defence cases with political aspirations for the rule of law and constitutional democracy.52

Zhang Sizhi, born 1947 and known among Chinese lawyers as “the conscience of lawyers”, is the human rights lawyer with the highest prestige in China today, although he mocks the fact that he has never won a case. This prestige comes with his seniority as a long time CCP member, as a Rightist serving in a labour camp for 15 years during the 1950s and 1960s, and as a human rights advocate and a defense lawyer for prominent state enemies ranging from the “Lin Biao Clique” and the “Gang of Four” to Wei Jingsheng, Wang Juntao and Bao Tong since 1980. Zhang has fought for human rights and judicial independence for decades and believes that every lawyer should be a human rights advocate. Awarded the 2008 Petra Kelly Prize by the Heinrich Böll Foundation for his “exceptional commitment to human rights and the establishment of the rule of law in China”, Zhang was praised internationally for “shaping China’s difficult path towards democracy and the rule of law” in his unique way.53

Following in Zhang Sizhi’s path are a generation of younger Chinese human rights lawyers, including Mo Shaoping (born 1958) in Beijing who has defended tens of political dissidents; Zheng Enchong (born 1950) in Shanghai who was sentenced to 3 years in prison in 2003 for representing evicted Shanghai residents in a lawsuit against real estate developers and the local government; Li Baiguang (born 1968) in Beijing who was arrested in 2004 for representing peasants in Fujian Province fighting for their land rights; Zhu Jiuhu (born 1966) in Beijing who was arrested in Shaanxi in 2005 for representing oil-field operators in Shaanxi who were arbitrarily stripped of contractual right to operate oil wells by the local government without proper compensation; Guo Guoting (born 1958) in Shanghai, whose licence was suspended in 2005 for representing political dissidents and Falun Gong practitioners; Gao Zhisheng (born 1966) in Beijing, who in 2006 was sentenced to 3 years in prison with 5 years of probation and whose law firm was shut down by the government for representing political dissidents and Falun Gong practitioners; Li Heping in Beijing who was beaten by secret police in 2007 and 2008 for representing political dissidents, Falun Gong practitioners and family church Christians; Teng Biao in Beijing who was abducted and detained by secret police for representing political dissidents, Falun Gong practitioners and family church Christians; Pu zhiqiang (born 1965) in Beijing who regularly represents political dissidents; Zhang Xianshui (born 1967) in Beijing who regular represents political dissidents and family church Christians; and Xu Zhiyong (born 1965) in Beijing who focuses on the cases of wronged petitioners.54 It is interesting to note that many of these human rights lawyers are also Christians.

Liberal intellectuals and rights lawyers commemorate the first anniversary of the death of liberal scholar Bao Zunxin at his tomb, October 2008. Rights lawyer Mo Shaoping holds the spade. Others include liberal intellectuals Yu Haocheng (blue jacket and hat, centre), Liu Xiaobo (black leather jacket , fourth from the right), Zhang Zuhua, Jiang Qisheng and Yu Jie; and rights lawyers Ten Biao and Pu Zhiqiang. All are prominent Charter 08 signers.

The clashes between rights lawyers and the party-state indicate profound contradictions in current legal and political systems. On the one hand, since 1978 when the legal profession did not exist and there were only two laws (the constitution and marriage law), remarkable legal reforms have taken place, such as importing legal institutions from the West, establishing a modern court system, enacting hundreds of laws, establishing hundreds of law schools, and participating in the international human rights regime.55 On the other hand, the Chinese Communist Party seeks to maintain a monopoly on political power and the entire power structure of the Leninist party-state, creating intrinsic contradictions between the rule of law and the supremacy of the Party. The constitution is granted the “highest legal authority”; courts are granted power to handle legal cases; and legal norms and procedures are created to protect citizens against abuses. However, under the concept of “socialist rule of law”, the principle of “Party leadership” must be upheld and Party power must not be undermined by law. As a consequence, rights lawyers are punished when they cross the arbitrary line drawn by the Party, although the authorities have refrained from suppressing the legal activism of rights lawyers entirely, at least partly because they operate carefully within the law and use China’s judicial system to advance their aims.

Grassroots rights activists. Legal activism of human rights lawyers has led to the emergence of a vibrant “rights defence movement” (weiquan yundong) since 2003, which can be defined as assertion of human rights through litigation (falü susong) supplemented by the pressure of public opinion (yulun yali).56 Rights lawyers’ leadership of the emerging “rights defence movement ” is shared with grassroots human rights activists, an encouraging indication that liberalism has reached down to the bottom of Chinese society.

Chen Guangcheng (born 1971), a blind “barefoot lawyer” who could not acquire a formal licence to practice law but managed to audit law classes and learn enough to advise fellow villagers when they sought his assistance on legal issues, is a typical grassroots activist fighting at the forefront of the “rights defence movement”. In early 2005, Chen exposed harsh illegal measures by local authorities enforcing the one-child policy in Linyi County, Shandong province. Family planning officials there forced thousands of people to undergo sterilization or to abort pregnancies. The officials were also accused of detaining and torturing relatives of people who had evaded the forced measures. Chinese national regulations prohibit such brutal measures, but they have been common practices throughout the country, especially in the 1980s and 1990s. Chen filed a class-action lawsuit on the women’s behalf against Linyi officials and drew attention to the plight of the villagers. He also travelled to Beijing in June 2005 to seek redress. When local authorities arrested Chen in September 2005, human rights lawyers from Shandong and Beijing immediately formed a defense team and demanded a fair trial, only to be beaten, detained and barred from the court room. After much delay Chen was tried in November 2006 and sentenced to four years and three months in prison on charges of “damaging property and organising a mob to disturb traffic”.

Similarly, Yang Maodong (pen name Guo Feixiong, born 1966) has also been imprisoned for rights activism on behalf of villagers. In July 2005, Taishi villagers in Panyu County, Guangdong, attempted to recall a corrupt village head only to face crackdowns by the local government and police. Civil rights activists and Chinese and foreign journalists who went to report on the incident were blocked or threatened. With other rights activists Guo, who had worked in Guangdong for many years as a private publisher and in other capacities, provided legal advice to the villagers in his capacity as a legal adviser of the Beijing-based Zhisheng Law Firm. Repeatedly detained, beaten and harassed, he was finally arrested in September 2006. In November 2007 Guo was sentenced to five years in prison on charges of “illegal business dealings”. The sentences to Chen, Guo and others send powerful signals to lawyers who dare to defend citizens against official malfeasance.

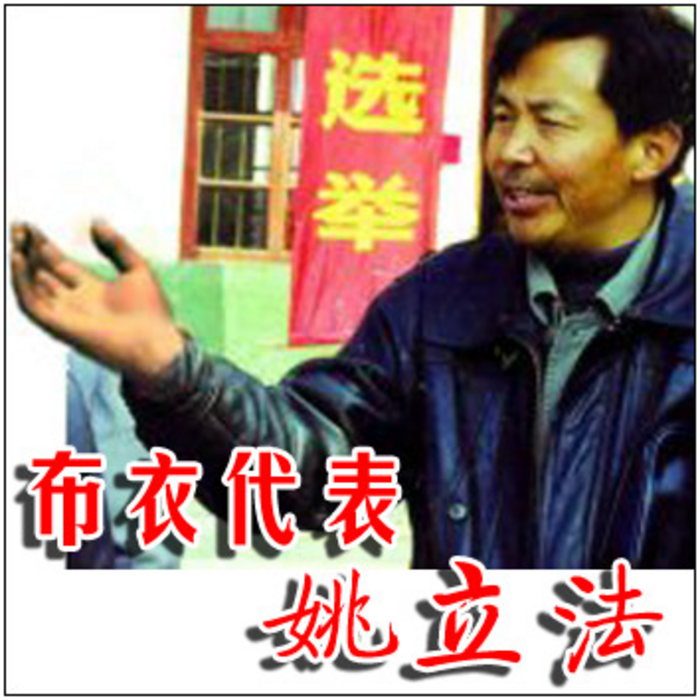

Yao Lifa (born 1958) of Qianjiang City in Hubei is the first deputy to be elected through self-nomination to a municipal-level people’s congress. Yao, who runs a vocational school education program and teaches in an elementary school, began competing for a seat in the local people’s congress in 1987, when the election law was first promulgated. The law allows for self-nominated candidates, and Yao used this provision to run for office. Twelve years later, in 1998, he finally succeeded. Over the course of the next five years, Yao was a busy and controversial figure—he raised 187 of the 459 suggestions, opinions, and criticisms presented to the local people’s congress. Yao has campaigned on issues of excessive taxes and levies, seizures, corruption, and access to health care. Sensing a mandate, he railed against the detention of peasants who refused to pay illegal fees, collected more than 10,000 signatures criticizing a Party official, and denounced the waste of public money on dubious projects.57 With Yao’s example and help, more independent candidates have turned to grassroots democracy; a small number have won seats in local congresses.

Election campaign poster for Yao Lifa.

Massive environmental protests represent another new social movement arena in China. Apart from the growing claim of victimhood through official channels, protests led by environmental non-governmental organisations (ENGOs) and other popular actions are increasing rapidly. According to Pan Yue, deputy minister for State Environmental Protection, pollution-induced mass incidents grew about twelve times in ten years between 1995-2005, an increase of 29% every year, with more than 50,000 pollution disputes across the country in 2005 alone.58 Yu Xiaogang (born 1951) in Yunnan is a grassroots environmentalist who set up the ENGO Green Watershed and succeeded for the first time in China in involving local villagers in watershed projects. His campaigns have helped raise consciousness of environmental protection among both villagers and government officials who began to pay attention to the socioeconomic impact of dam construction on local Chinese communities. Yu played a key role during 2003 and 2004 in blocking the Yunnan provincial government’s plans to construct 13 new dams on the Nu River, one of the Three Parallel Rivers – the Nu, Jinsha (Yangzi) and the Lancang (Mekong), for which he was awarded the prestigious Goldman Environmental Prize in 2006.

Wu Xian (born 1987) in Fujian is a young environmentalist who played an important role in the Xiamen PX (Paracylene) Project Incident in 2007. When Wu, a small karaoke bar manager, heard about the plan for the giant petrochemical plant (investment of US$1.41 billion) with strong political connections, he immediately set up an online discussion group and urged Xiamen residents to protest against the plant. Local residents eventually launched strong campaigns that forced the plant to be relocated to a safer location.

Protest of Xiamen residents against the Xiamen PX (Paracylene) Project, June 2007.

Likewise, Yang Yang (born 1977) in Shanghai, a shy young saleswoman, is also an environmental protection activist who has achieved great success. When she learned from her housing development’s electronic bulletin board of the city’s plans to extend Shanghai’s futuristic magnetic levitation, or maglev, train line within 30 meters of her house, angered by the noise and radiation pollution, the misuse of taxpayers’ money and the effect on property values, she began networking with other opponents both in her neighbourhood and all along the planned train route. Word of opposition sentiment quickly gathered momentum and Yang and her fellow residents organised a “collective walk” (jiti sanbu) on the People’s Square. On 12 Jan 2008, a sunny Saturday afternoon, Yang found herself in Shanghai’s most important public square, with a few thousand other disgruntled residents in one of the largest demonstrations the city had seen in recent years. Yielding to the pressure, the Shanghai government put on hold the Maglev Train project to connect the Hongqiao International Airport to the Pudong International Airport.

Shanghai residents’ “collective walk” at People’s Square in protest against the Maglev Train project, January 2008.

In every one of these events, liberal bloggers and “citizen reporters” (gongmin jizhe) launched Internet campaigns and played important roles in social mobilisation. Hu Jia (born 1973) joined ENGO Friends of Nature in 1996 and participated in protests against deforestation in northern China. He then he became an AIDS activist and rights activist and published regularly on the internet criticizing government abuses of human rights. He was detained by the police several times and sentenced in April 2008 to three and a half years in prison for “inciting subversion of state power”. Ai Weiwei (born 1957), a designer by profession, in December 2008 took a team to collect data on the Wenchuan earthquake victims for government compensation and punishment of those responsible for shoddy construction resulting in fatal injuries. Ai quickly became one of the most popular bloggers in China, attacking corruption and power abuses. Another extremely popular blogger is Yang Hengjun (born 1965) who earned his BA in Politics from Fudan University and PhD in China Studies from The University of Technology, Sydney. Yang became a freelance writer well-known for his penetrating current affairs commentaries.

It bears noting that, given internal diversity within the liberal camp, what Charter 08 has expressed is a minimum consensus. Even so, some leading liberals have expressed reservations and have not signed the documents. Leading liberals within the CCP, such as Li Rui and Zhu Houze, regarded Charter 08 as a direct confrontation with the Party leadership and politely declined the invitation to join.59 Their concern is shared by some leading liberal intellectuals such as Zhu Xueqin and Xiao Han who held that the document should have allowed greater space to accommodate the ruling communist party.60 Some leading social democrats within the liberal camp, such as Qin Hui, did not sign the document either, on the ground that it did not go far enough in spelling out demands for social welfare and economic rights of the poor.61

Conclusion

Charter 08 is the most important collective expression of Chinese liberal thought to emerge since the founding of the People’s Republic in 1949. It embodies Chinese liberals’ sincere invitation to both the government and the public for constructive interaction and negotiation to effect and manage a fundamental political change toward constitutional democracy. Despite the Communist Party’s official agenda for democratic reform and human rights, the current leadership lacks the confidence to directly engage the Charter 08 framers and signers in theoretical debate on the issues raised, or to launch all-out war against signatories of the document. After hesitating for one year, the Chinese authorities severely punished Liu Xiaobo, but at this writing have left other signatories alone, although most of the 303 original signatories were “summoned for interrogations” (chuan huan) by the police within a month of the publication of the document. Out of fear of organized opposition, the authorities have emphasized blocking circulation of the document and “punishing one as a warning to others” to minimize the impact of Charter 08. This strategy has not succeeded in forcing one single signatory to withdraw, nor has it prevented more than ten thousand Chinese at home and abroad from adding their names to the document. However, the strategy of Chinese authorities has had a certain effect, at least for the time being, in leading many more who share the values and aspirations of Charter 08 to remain silent. In the long run, the proposals made in Charter 08 could serve as a guide for the emergence of a genuine Chinese democracy.

Feng Chongyi is Associate Professor in China Studies at the University of Technology, Sydney, and adjunct Professor of History, Nankai University, Tianjin. He is author of numerous books in English and Chinese including Peasant Consciousness and China; From Sinification to Globalisation; The Wisdom of Reconciliation: China’s Road to Liberal Democracy and Liberalism within the CCP: From Chen Duxiu to Lishenzhi. He is also the editor of Constitutional Government and China; Li Shenzhi and the Fate of Liberalism in China; Constitutional Government and China; and Constitutional Democracy and Harmonious Society. He wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

This article, originally published on January 11, 2010, is being republished with a new introduction on October 11, 2010 following the award of the Nobel Peace Prize to Liu Xiaobo.

Recommended citation: Feng Chongyi, “Charter 08, the Troubled History and Future of Chinese Liberalism,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 41-5-10, October 11, 2010.

Notes

1 The sentence also sent shock waves through the international community, the government of the United States in particular, which had hailed the Charter and asked for the release of Liu Xiaobo.

2 For instance, Feng Chongyi and Yang Hengjun, ‘Mingnian qibu, sannian chengjiu xianzheng daye’ (Start Next Year and Achieve Constitutional Democracy in China within Three Years).

3 Link.

4 There are two slightly different versions of the text available in English. One English text was provided by Perry Link whose translation was based on a draft version of the original text and published in The New York Times Book Review, volume 56, number 1, January 15, 2009; the other translation with the list of 303 signatories, based on the finalised version of the original text, was provided by Human Rights in China and is available at its website, which also provides a link to a Chinese text in both full and simplified Chinese characters. The text in other languages, such as Japanese and French can be found on this website.

5 Li Shenzhi, ‘Hongyang Beida de ziyou zhuyi chuantong, (Promoting and developing the liberal tradition of Beijing University), in Liu Junning, ed., Ziyou zhuyi de xiansheng: Beida chuantong yu jinxiandai Zhongguo (The harbinger of liberalism: The tradition of Beijing University and modern China), (Beijing: Zhongguo renshi chubanshe, 1998), 1-5. Similar ideas had been put forward by others earlier, albeit with much less impact. For example, see Xu Liangying, ‘Renquan guannian he xiandai minzhu lilun’ (The concept of human rights and modern theory of democracy), Tanshuo (Exploration), August 1993; also in Xu Liangying, Kexue Minzhu Lixing: Xu Liangying Wenji (Science, Democracy and Reason: Selected Works of Xu Liangying), New York: Mirror Books, 2001, p.258-276.

6 See Bao Tong’s recent work Zhongguo de yousi (China’s Anxiety), Hong Kong: Taipingyang Century Publishing House, 2000; Hu Jiwei, “Xin chun fang yan: yige lao gongchandang yuan de shensi ” (Unrestrained comments at new spring: reflections by a senior member of the CCP), Beijing zhi chun (Beijing Spring), no. 34, March 1996, p.6-14; Hu Jiwei, ‘Mingbian xingshuai zhilu, huainian Hu Zhao xin zheng’ (Understanding the causes for the rise and decline in commemoration of new undertakings by Hu Yaobang and Zhao Ziyang); Li Rui, “Yingjie xin siji yao sijiang” (Four stresses to usher in the new century), Yanhuang chunqiu (Chronicles of China), no. 12,1999, p.5; Li Shenzhi, ‘Fifty years of storms and disturbance’, China Perspectives, no. 32 (November-December 2000), p. 5-12; Guan Shan, ‘Ren Zhongyi tan Deng Xiaoping yu Guangdong gaige kaifang’ (Ren Zhongyi’s talks on Deng Xiaoping and the reform and opening in Guangdong), Tongzhou Gongjin (Advance in the Same Boat), no.8, 2004, p.6-14; Xie Tao, ‘Minzhu shehui zhuyi moshi yu zhongguo qiantu’ (The model of democratic socialism and the future of China), Yanhuang chunqiu (Chronicles of China), no. 2, 2007, p1-8.

7 For details see Feng Chongyi, ‘The Third Way: The Question of Equity as a Bone of Contention Between Intellectual Currents’, Contemporary Chinese Thought, 34: 4, Summer 2003, p. 75-93.

8 For a discussion by leading liberals on China’s household registration system from an historical perspective, see Qin Hui, ‘Qiangu Cangsang hua huji (Vicissitudes of Household Registration System through the Ages), in Qin Hui, Shijian Ziyou (Practising Freedom), Zhejiang People’s Publishing House, 2004, p.3-10.

9 Qin Hui (Bian Wu), ‘Gongzheng zhishang lun’ (On Supremacy of Justice), Dongfang (Orient), 1994:6; Qin Hui (Bian Wu), ‘Zailun gongzheng zhishang: qidian gongzheng ruhe keneng’ (The Second Essay On Supremacy of Justice: Possibility of Justice as the Starting Point), Dongfang (Orient), 1995:2; Qin Hui, ‘Shehui gongzheng yu zhongguo gaige de jingyan jiaoxun’ (Social Justice and the Lessons of Reform in China), in Qin Hui, Wenti yu Zhuyi (Issues and Isms), Changchun: Changchun Publishing House, 1999, p. 33-40; Qin Hui, ‘Ziyou zhuyi, shehui minzu zhuyi yu dangdai zhongguo “wenti”’, Zhanlue yu Guangli (Strategy and Management), 2000:5, p. 83-91; He Qinglian, Xiandaihuade Xianjing (The Pitfall of Modernisation), Beijing: China Today Publishing House, 1998; Xu Youyu, ‘Ziyouzhuyi yu dangdai zhongguo’ (Liberalism and Contemporary China), Kaifang Shidai (Open Times), 1999:3, p.43-51; Xu Youyu, ‘Ziyou zhuyi, falankefu xuepai ji qita’ (Liberalism, Frankfurt School and Others), in Xu Youyu, Ziyoude Yanshuo (Liberal Discourse), Changchun Publishing House, 1999, p. 305-318; Zhu Xueqin, ‘1998: ziyouzhuyi xueli de yanshuo’ (Discourse on Liberalism in China in 1998), Zhu Xueqin, Shuzai li de geming (Revolution in the Study), Changchun: Changchun Publishing House, 1999, p.380-399.

10 Liu Junning, ‘Ziyou zhuiyi yu gongzheng: dui ruogan jienan de huida’ (Liberalism and Justice: a reply to some criticisms), Dandai Zhongguo Yanjiu (Modern China Studies), No.4, 2000; Qin Hui, ‘Chanquan gaige yu minzhu’ (Democracy and Property Rights Reform).

11 Xu Youyu, ‘Dangdai zhongguo shehui sixiang de fenhua he dui’ (Ideological Division in Contemporary China).

12 He Qinglian, Xiandaihuade Xianjing, p. 4.

13 Zhu Xueqin, ‘Ziyouzhuyi yu xin zuopai fenqi hezai’, ‘What Is the Difference Between Liberals and the New Left’, in Zhu Xueqin, Shuzai li de geming (Revolution in the Study), Changchun: Changchun Publishing House, 1999, p.419-420. There are those who argue that state socialism cannot be reformed and market socialism is an illusion, simply because market coordination and bureaucratic coordination are not compatible. See Janos Kornai, The Socialist System: the Political Economy of Communism, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1992.

14 Qin Hui, ‘Zhongguo jingji fazhan de di renquan youshi’ (The Advantage of Poor Human Rights in China’s Economic Development).

15 Xu Youyu, ‘Jiushi niandai de shehui sichao’ (Intellectual Trends in the 1990s), in Xu Youyu, Ziyoude Yanshuo (Liberal Discourse), Changchun: Changchun Publishing House, 1999, p. 257, 260.

16 Qin Hui, ‘Shehui gongzheng yu xueshu liangxin’ (Social Justice and Academic Conscience), in Li Shitao (ed), Ziyou zhuyizhizheng yu zhongguo sixiangjie de fenhua (Debate on Liberalism and the Split in the Chinese World of Thought), Shidai Wenyi Publishing House, 2000, P.395-396.

17 Li Buyun, ‘Cong fazhi dao fazhi: ershi nian gai yige zi’ (From the Rule by Law to the Rule of Law: taking 20 years to change one word), Faxue (Legal Studies), no.7, 1999; The Law Institute of Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, ed., Zhongguo fazhi sanshi nian (The Rule of Law in China during the Past 30 Years, 1978-2008), Beijing: Social Sciences Academic Press, 2008, p.59-65.

18 Feng Chongyi, ‘The Rights Defence Movement, Rights Defence Lawyers and Prospects for Constitutional Democracy in China’, Cosmopolitan Civil Societies: An Interdisciplinary Journal, Vol 1, No 3 (2009).

19 Nicholas D. Kristof, “China Sees ‘Market-Leninism’ as Way to Future,” The New York Times, September 6, 1993.

20 Andrew Nathan, ‘Authoritarian Resilience’, Journal of Democracy 14, no. 1, 2003, pp.6–17; Minxin Pei, China’s Trapped Transition: The Limits of Developmental Autocracy, Harvard University Press, 2006.

21 Feng Chongyi, ‘The Liberal Camp in Post-June 4th China’, China Perspectives, no.2 2009, p.30-42

22 The term “liberals” in this article refers to those who firmly believe in philosophical, economic, and political liberalism and openly defend their belief in practice. In the context of contemporary China a clear distinction can be made between liberals and semi-liberals, the latter being proponents of economic liberalism who support the project of privatization and marketization but reject political liberalism and oppose or lack interest in the democratization project. For details see Feng Chongyi, ‘The Return of Liberalism and Social Democracy: Breaking through the Barriers of State Socialism, Nationalism, and Cynicism in Contemporary China’, Issues & Studies, 39: 3, September 2003, p. 1-31.

23 Zhu Xueqin, “1998: ziyou zhuyi xueli de yanshuo” (Discourse on liberalism in China in 1998), Nanfang Zhoumo (Southern Weekend), 25 December 1998; Liu Junning, “Ziyou zhuyi: jiushi niandaide ‘busuzhike’” (Liberalism: An “unexpected guest” of the 1990s), Nanfang zhoumo (Southern Weekend), May 29, 1999; Xu Youyu, “Ziyou zhuyi yu dangdai Zhongguo” (Liberalism and contemporary China), Kaifang shidai (Open Times), no. 128, May/June 1999.

24 For the impact of human rights discourse on China, see Merle Goldman, From Comrade to citizen: The struggle for Political Rights in China, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2005; also Michael C. Davis, ed., Human Rights and Chinese Values: Legal, Philosophical and Political Perspectives, New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

25 The first conference exclusively comprised of Chinese liberals was organised by Feng Chongyi at University of Technology, Sydney on Constitutional Government and China, January 2003, leading to publication of the book series Zhongguo Ziyouzhuyi Luncong (Chinese Liberalism Series).

26 For Zhu’s liberal ideas see Zhu Xueqin, Daode lixiang guo de fumie (Downfall of the Moral Utopia), Shanghai: Sanlian, 2004; and Zhu Xueqin, Shuzhaili de geming (Revolution in the Study), Changchun: Changchun Publishing House, 1999.

27 For Xu’s liberal ideas see Xu Youyu, Ziyou de yanshuo (Discourse on Liberalism), Changchun: Changchun Publishing House, 1999

28 For Qin’s liberal ideas, see Qin Hui, Wenti yu zhuyi (Issues and isms; and Qin Hui, Shijian ziyou (Practising Liberalism), Hangzhou: Zhejiang People’s Publishing House, 2004.

29 For He’s liberal ideas, see He Weifang, Sifa de linian yu zhidu (Judicial Ideals and Institutions), Beijing: Chinese University of Political Science and Law Publishing House, 1998; and He Weifang, Yunsong zhengyi de fangshi (Ways to Carry Out Justice), Shanghai: Sanlian Books, 2003.

30 For Liu’s liberal ideas, see Liu Junning, Minzhu, gonghe xianzheng: ziyou zhuyi sixiang yanjiu (Democracy, Republicanism and Constitutional Government: A Study of Liberalism), Shanghai: Sanlian Books, 1998.

31 For Zhang’s liberal ideas, see Zhang Boshu, Zhongguo xianzheng gaige kexingxing yanjiu baogao (A Study of the Feasibility of Constitutional Democracy Reform in China), Hong Kong: Chenzhong Books, 2008; and Zhang Boshu, Cong wusi dao liusi: 20 shiji zhongguo zhuanzhi zhuyi pipan (From May 4 to June 4: Criticism of Chinese Despotism in the 20th Century), Hong Kong: Chenzhong Books, 2008.

32 For Sun’s liberal ideas, see Sun Liping, Boyi: duanlie shehui de liyi chongtu yu hexie (Contestations: Conflict of Interests and Social Harmony in a Rift Society), Beijing: Social sciences Academic Press, 2006.

33 For their liberal ideas, see Zhou Qiren, Chanquan yu zhidu bianqian (Property Rights and Institutional Change), Beijing: Beijing University Press 2005; Wang Dingding, Yongyuan de paihuai (Wavering Forever), Beijing: Social sciences Academic Press, 002; and Zhang Weiying, Qiye lilun yu zhongguo qiye gaige (Enterprise Theory and Enterprise Reform in China), Beijing: Beijing University Press,1999.

34 See Feng Chongyi, ‘Li Shenzhi he zhonggong dangnei ziyou minzhu pai’ (Li Shenzhi and Liberal Democrats within the Chinese Communist Party), in Feng Chongyi, ed., Li Shenzhi yu ziyou zhuyi zai zhongguo de mingyun (Li Shenzhi and the Fate of Liberalism in China), Hong Kong Press for Social Sciences, 2004, p. 121-146; and Feng Chongyi, ‘Democrats within the Chinese Communist Party since 1989’, Journal of Contemporary China, vol.17, no. 57, November 2008, p. 673-688.

35 For Zhao’s liberal ideas in his final years, see Zhao Ziyang, The Secret Journal of Zhao Ziyang, Hong Kong: New Century Press, 2009; Zong Fengming, Zhao Ziyang: ruanjin zhong de tanhua (Zhao Ziyang: Captive Conversations), Hong Kong, Open Publishing House, 2007. During the 1980s Hu Yaobang was more liberal politicly than Zhao Ziyang, but Hu did not have opportunities to convert from a Marxist to a liberal.

36 For details of their activities and the crackdown by the Chinese communist regime, Teresa Wright, ‘Intellectuals and the Politics of Protest: The case of the China Democracy Party’, in Edward Gu and Merle Goldman, eds., Chinese Intellectuals Between State and Market, London and New York: RoutledgeCurzon, 2004, p.158-180; see also Merle Goldman, From Comrade to citizen: The struggle for Political Rights in China, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2005, chapter 6.

37 Not counting contacts during ancient times, the Chinese have experienced modern Christianity for more than three centuries since the Ming Dynasty, which received the first groups of Western missionaries. Millions of Chinese were converted to Christians during the late Qing and the Republican period when, in spite of many troubles, Christianity was legal and welcome as a healthy religion and the Churches were allowed to be independent from the government, contributing to the development of modern education, modern science, modern medicine, and modern charity. Many Chinese reformers saw the trinity of modern industry (science), democracy and Christianity as the secret of Western success. This development was brought to an end in 1949 when China was taken over by the communist regime, which regarded Christianity as a hostile force and brought it under strict government control.

38 Yang Xiaokai, ‘Jingji gaige yu xianzheng zhuanxing’ (Economic Reform and Transformation to Constitutional Democracy).

39 Yu Jianrong, ‘Jidujiao de fazhan yu zhongguo shehui wending: yu liangwei jidujiao jiating jiaohui peixun shi de duihua’ (Development of Christianity and Social Stability in China: dialogue with two trainers of Christian family churches ); Yu Jie, ‘Zhongguo dangdai zhishi fenzi de guixin licheng (The conversion of intellectuals to Christianity in contemporary China), in Yu Jie, Bai Zhou Jiangjin (Daylight Approaching), Hong Kong: Chenzhong Books, 2008, p. 241-249.

40 The organization was founded in the early 1950s by a group of government officials and church leaders who were sympathetic to the new Communist regime. It took its name from the principles of self-government, self-propagation, and self-support, which foreign missionaries years before had set forth as goals for the Chinese Church. Thousands of Chinese Christians refused to join the government-run organization, precisely because they wanted to maintain their independence and the principles of self-government, self-propagation, and self-support. After 1955 the independent Christians were driven underground and many were jailed. The first known Chinese “family church” was founded by a senior priest Yuan Xiangchen in Beijing in 1980, when he was released after imprisonment of 21 years. After three decades of quiet development, members of “family churches” are several times more numerous than those of official churches, which many devoted Christians view as harmful to the integrity of their belief precisely because of the close relationship with the government. See Yu Jianrong ‘Zhongguo jidujiao jiating jiaohui xiang hechu qu: yu jiating jiaohui renshi de duihua’ (Whither the Christian Family Churches in China: dialogue with Christians of Family Churches).

41 Apart from the atheist state ideology, the basic institutional obstacle to legalize family churches in China is the state corporatist approach adopted by the party-state toward civil society, allowing only one association for one profession. The Religious Affairs Office and the Civil Affairs Bureau do not approve the registration of any Christian churches unless they are affiliated to the Three-Self Patriotic Movement Committee. Most Chinese Christians, as their counterparts elsewhere, believe it is unacceptable to reduce the churches to subsidiary bodies of the state. For an analysis of contradictions and flaws in the laws and regulations governing religious affairs in China, see Wang Yi, ‘Zongjiao fagui: dangqian de zhengjiao chongti jiqi qushi’ (The Religious Laws and Regulations: conflicts between religions and the government at present and the trends in the future).