The Copenhagen Challenge: China, India, Brazil and South Africa at the Barricades (Chinese translation available)

Peter Lee with a post-mortem on Copenhagen’s COP15 by Eric Johnston

On January 25, 2010, the West was handed the bill for continuing the Copenhagen climate change process: $10 billion for the developing world, due immediately.

The invoice was delivered by Brazil, South Africa, India, and China—the so-called “BASIC” nations–after their meeting in New Delhi on January 25.

Representatives of the BASIC nations, Brazil, India, China and South Africa

The four nations also transmitted a challenge from the world’s rising economic superpowers to the West’s continued leadership of the global climate effort.

In their joint communiqué, the four nations promised to submit their emissions reductions goals—“voluntary mitigation actions” in the jargon—to the UN’s Framework Convention on Climate Change by January 31. The other substantive point covered was urging the developed world to pony up the $10 billion it had promised at Copenhagen in December 2009:

The Ministers called for the early flow of the pledged $10 bn in 2010 with focus on the least developed countries, small island developing states and countries of Africa. (link)

As the Indian media pointed out, this was a move by the BASIC countries to “claim the moral high ground”. In fact, the battle for the moral high ground—and political advantage—has been driving the international climate change negotiations since November of 2009. That was when the United States conceded that the U.S. Congress would not pass any climate change legislation before the Copenhagen climate summit.

With President Obama unable to make any binding commitments on behalf of the United States, the best Copenhagen could hope to achieve was a political agreement—with a healthy dose of political posturing.

The Obama administration made an interesting but perhaps shortsighted choice in its selection of political targets—China and the other BASIC countries. As a result, the chances for coordinated international action to mitigate global warming by reducing greenhouse gases—never good to start with—have become virtually nonexistent.

The United States is a late and still ambivalent player in the global warming game. The United States Congress never ratified the Kyoto Treaty—a document designed to impose legally binding emissions limits on the 40 Annex 1 signatories representing the developed world.

President Obama came to office determined to restructure the U.S. economy around a vigorous response to climate change. His approach was to legislate U.S. limits on greenhouse gases, then leverage the U.S. commitment into a robust successor treaty to Kyoto.

Unfortunately, the critical first step—Senate passage of the Waxman-Markey “American Clean Energy and Security Act” a.k.a. ACES—fell victim to the delaying tactics of the Republicans and the Obama administration’s strategic decision to achieve a big healthcare win first and parlay that victory into further legislative triumphs down the road.

As healthcare reform was slowly and cruelly eviscerated in the Senate, it was clear that Waxman-Markey was a project for 2010 at best, and President Obama would have to attend Copenhagen under the Bush cloud—as president of a country that had never ratified the Kyoto treaty or passed any legislation to limit greenhouse gases.

Instead of punting and hoping to get the ball back in time to try to score some points at the 2010 climate meeting in Mexico (to use an American football metaphor), the Obama administration made the decision to ignore its lack of leverage and nevertheless try to advance its climate change political agenda by asserting U.S. leadership at Copenhagen in December 2009.

That meant dealing with the China problem.

There is no question that China is at the heart of the climate change dilemma. The Kyoto Treaty gave China and the other developing countries a free pass while imposing legally binding emissions limits on the developed countries of Europe, East Asia, Australasia, and Russia.

But nobody wants to give China a free pass anymore. China now has the distinction of being the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases. And it’s going to get worse. As China’s population grows and prospers and demands all the nice, energy-intensive things like automobiles and electric appliances, its production of greenhouse gases will inevitably increase, perhaps growing by 80% over the base year of 2000 by 2030.

Nevertheless, China is a prominent participant in the world climate change conversation.

To a certain extent, strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions dovetail with its own energy-security and energy-efficiency strategies. Its reliance on coal is an insurmountable obstacle to any effort to reduce its emissions on an absolute scale in the near future, but it is committed to reducing its “energy intensity”—energy consumed per capita.

China’s vision of its role in a future greenhouse gas emissions regime probably draws on the example of Russia, the “invisible man” among the superpowers in climate change negotiations.

With the post-1990 collapse of its heavy industry, Russia is luxuriating under a generous Kyoto cap negotiated with the USSR, selling hundreds of millions of dollars in offsets to Europe, and working hard to avoid any scrutiny, let alone renegotiation, of its Kyoto obligations.

No doubt China would also like to negotiate an advantageous emissions cap and then make a little bit of financial hay by coming in under the cap and selling offsets as well as green technology and equipment to the developed world.

In the context of carbon trade, China has engaged in detailed discussions on the monitoring, reporting, and verification or “MRV” issue—the need to document emissions and reductions in order to create a tradable financial instrument. Indeed, it was claimed that China and the United States had achieved a meeting of the minds on MRV during President Obama’s trip to China in November 2009, paving the way for resolution of the issue at Copenhagen.

Barack Obama and Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao

That was possibly the case. Certainly, there was a lot of discussion about MRV in the context of sovereignty, applying it in different degrees depending on whether mitigation projects were undertaken locally or were foreign-funded, or would be eligible for some international payday under global cap-and-trade.

If Copenhagen had stuck to the climate change lingua franca of “MRV”, things might have gone much more smoothly.

However, “MRV” is not sufficiently red meat for America’s contentious politics. Any international treaty that would impose legally binding limits on the United States would have to make sufficiently onerous demands on China and the other polluters in the developing world in order to have any chance of passing the hostile scrutiny of the U.S. Senate and gain the 67 votes needed for ratification.

Indeed, the received wisdom inside the United States is that not even the Waxman-Markey bill, a piece of domestic legislation, can get the sixty votes it needs in the Senate unless China is pulling its weight. China-bashing being what it is, it was stated that “transparency” and “international verification” of China’s efforts—the adversarial terms usually reserved for arms, trade, and human rights issues and springing from the assumption that China can’t be trusted–were a necessary condition for pushing climate change legislation through the U.S. Congress.

As the political newsletter The Hill put it:

Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse (D-R.I.), a liberal who strongly backs mandatory U.S. emissions curbs, also said the China verification issue is important.

“There is a sense that we have been burned on the free trade agreements in terms of noncompliance,” Whitehouse said.

In addition to his own concerns, Whitehouse said that an absence of outside verification of China’s efforts would provide fuel for critics of climate legislation.

“It helps the opponents of the bill who argue it will lead to an exodus of jobs because of comparative advantage problems,” he said.

The Obama administration came to Copenhagen determined to talk about “transparency” instead of “MRV”–and demanded that China accept its demand for “transparency” or face a loss of its standing with the lesser developed countries.

In advance of President Obama’s arrival, Secretary of State Hillary Clinton laid out the American position:

…in the context of a strong accord in which all major economies stand behind meaningful mitigation actions and provide full transparency as to their implementation, the United States is prepared to work with other countries toward a goal of jointly mobilizing $100 billion a year by 2020 to address the climate change needs of developing countries.

In response to a question about how China fit in, she stated:

Time and time again leading up to these negotiations, all the parties have committed themselves to pursuing an agreement that met the various standards, including transparency. It would be hard to imagine, speaking for the United States, that there could be the level of financial commitment that I have just announced in the absence of transparency from the second biggest emitter – and now I guess the first biggest emitter, and now nearly, if not already, the second biggest economy.

President Obama tried to play good cop after he arrived in Copenhagen:

“These measures need not be intrusive, or infringe upon sovereignty,” he said, in a direct reference to the concerns expressed by Chinese officials, who have been balking at proposed verification measures.

“They must, however, ensure that an accord is credible, and that we are living up to our obligations. For without such accountability, any agreement would be empty words on a page.”

Perhaps the Obama administration intended to act out some political kabuki for the benefit of the suspicious U.S. domestic audience: first use the tougher (and more loaded) term of “transparency” instead of the UN and tree-hugger-friendly “MRV”, and couch the exchange in terms of a demand that China live up to its responsibilities or risk the devastation of the developing world, then stage the mutual concessions and triumphant grip-and-grin of two tough negotiators to climax Copenhagen.

It is perhaps a telling point that Clinton’s ballyhooed summons to “transparency” was never defined and the final agreement largely regurgitated the standard MRV terms, concepts, and scope of application discussed at Bali in 2007 that China and the United States had been quietly negotiating for months.

However, whether by reason of diplomatic miscalculation or political calculation, the U.S. chose to employ a politically expedient but divisive and perhaps unnecessary tactic: using the public threat of withholding billions of dollars of climate adaptation aid for the developing world as a public club to gain Chinese acceptance of the “verification” regime.

The Chinese were not alone in seeing the U.S. stand as a cynical ploy to embarrass Beijing in front of the small and poor countries.

John Lee, a China critic writing at Foreign Policy, described the maneuver as “a clever trap”:

Having just announced that the United States would establish and contribute to a $100 billion international fund by 2020 to help poor countries cope with the challenge of climate change, Clinton added a nonnegotiable proviso: All other major nations would first be required to commit their emissions reduction to a binding agreement and submit these reductions to “transparent verification.” This condition was publicly reaffirmed by Obama, who argued that any agreement without verification would be “empty words on a page.”… The onus was now on Beijing to agree to standards of “transparent verification.” If it did not, poorer countries standing to benefit from the fund would blame China for breaking the deal. Clinton’s proposal had cunningly undermined Beijing’s leadership over the developing bloc of countries.

The Chinese response was unalloyed fury. China’s premier, Wen Jiabao skipped a meeting with President Obama to show his displeasure. When President Obama tracked down Premier Wen for an impromptu face to face, China’s top climate official, Xie Zhenhua, confronted the leader of the free world with an angry finger-pointing tirade—that Wen instructed his interpreter not to translate.

It appears that the Chinese felt blind-sided by the U.S. tactic and deeply resentful of its attempt to put China in the wrong at Copenhagen by linking “transparency” to the aid billions. Xie Zhenhua, who has presumably spent many months discussing the tedious minutiae of MRV with the United States, perhaps had good reason for his finger-wagging fury.

The Chinese were far from alone in their distaste for the U.S. tactics. America’s “clever trap” performed the amazing trick of uniting China, America’s designated strategic competitor and India, America’s designated counterweight to China, in a spirit of intense resentment at the unambiguous U.S. efforts to split the developing world bloc and undercut their diplomatic standing with the smaller nations of the developing world.

India’s Jairam Ramesh described the fallout from the U.S. tactics as follows:

“During the last day of the summit (18 December) when the talks had reached an impasse, it was the intention of European Nations and the US to announce the breakdown and hold the four Basic nations (India, China, Brazil and South Africa) accountable for its failure,” Environment Minister Jairam Ramesh said addressing the Aspen Institute of India recently.

Speaking about the talks on the concluding day of the Summit, he said the US President (Barack Obama) kept on saying to the head of state of Bangladesh and Maldives that “you are not going to get money (for climate steps) unless these four guys (BASIC nations) sign the Accord.”

He (Obama) made it categorically clear that any money flow to the developing countries will be linked to the Accord provided the four countries of BASIC group come on board, Ramesh said.

“Bangladesh Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina did ask me whether India will deny her country this money. This was the line taken by UK and Australia as well.

“Against this background, none of the heads of the four states wanted to be responsible for the breakdown of the talks. China was particularly wary being world’s largest green house gas emitter,” Ramesh recalled.

This “was the moral line taken at the summit and against this background the Accord was noted,” he added.

The Western press valiantly pitched in on the United States’ behalf in order to paint China as obstructionist.

The Independent obligingly offered up a classic inversion of blackmailer and blackmailee: China holds the world to ransom: Beijing accused of standing in the way of climate change treaty at Copenhagen as US throws down the gauntlet by backing $100bn fund to help poorest countries.

While piling on China for Copenhagen’s failure, the United States assiduously ignored the embarrassing fact of ostensible ally India’s move into the BASIC camp—and skated over the issue of how Washington’s conference planning found it lined up against both New Delhi and Beijing instead of playing one off against the other.

When one considers that the essence of U.S. diplomacy in Asia involves pushing China and India into opposition, forcing these two rivals into an alliance is a remarkable if dubious achievement.

India, for its part, was frank about its identity of interests with China, at least on the issue of climate change India has come out quite well in Copenhagen: Ramesh (Lead):

[Environment Minister] Ramesh said: “A notable feature of this conference is the manner in which the BASIC group of countries (Brazil, South Africa, India and China) coordinated their position.

“BASIC ministers met virtually on an hourly basis right through the conference; India and China worked very very closely together.”

The final Copenhagen document was an embarrassment—a three-page statement of non-binding principles cobbled together in a smoke-filled room by the U.S., the EU, and the newly-minted “BASIC” group without input from the small, poor, and at-risk nations—the G77–attending the massively hyped summit.

Post-summit finger pointing began almost immediately.

Speaking for the Western team, Ed Miliband condemned China for its intransigence.

In a widely-circulated article in the Guardian entitled How do I know China wrecked the Copenhagen deal? I was in the room, climate activist Mark Lynas provided an indignant account of what he characterized as Chinese “gutting” of the deal:

To those who would blame Obama and rich countries in general, know this: it was China’s representative who insisted that industrialised country targets, previously agreed as an 80% cut by 2050, be taken out of the deal. “Why can’t we even mention our own targets?” demanded a furious Angela Merkel. Australia’s prime minister, Kevin Rudd, was annoyed enough to bang his microphone. Brazil’s representative too pointed out the illogicality of China’s position. Why should rich countries not announce even this unilateral cut? The Chinese delegate said no, and I watched, aghast, as Merkel threw up her hands in despair and conceded the point. Now we know why – because China bet, correctly, that Obama would get the blame for the Copenhagen accord’s lack of ambition.

China, backed at times by India, then proceeded to take out all the numbers that mattered…

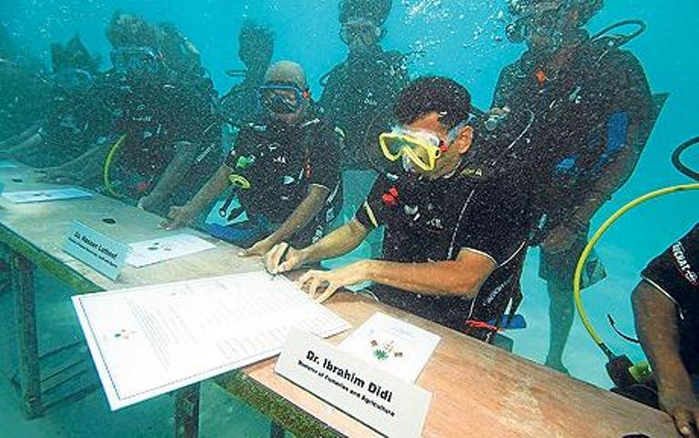

Actually, in his role as unpaid advisor to the Maldives, home of the underwater cabinet meeting, Mr. Lynas attended some of the larger confabs but was not “in the room” when the final deal was cut between the BASIC countries and the U.S.-led coalition.

Maldives underwater Cabinet Meeting

The United States showed up in Copenhagen as the one major power that had never ratified the Kyoto Treaty and with no legal mandate from its legislature to negotiate. It made an embarrassingly small pledge to reduce greenhouse gases (far below the heroic efforts of the EU), promised hundreds of billions of dollars of vapor aid that it had no expectation of funding itself, and tried to turn the negotiations into political theater that would strengthen the Obama administration’s hand back home.

Not surprisingly, China, the other BASIC countries, and many of the G77 saw the U.S. tactics as an effort to paper over the fact that the Obama administration saw no prospect of the U.S. Congress ever passing Kyoto and wanted to dodge the blame for collapse of the existing climate change regime by pinning the “obstructionist” tag on the developing world instead.

Indeed, they were well aware that Washington had already gained EU support in October 2009 for scrapping Kyoto and replacing it with a new regime (immortalized in the notorious “Danish text”) that relieved the developed world of some of its obligations (and the U.S. of its domestic political burden) by transferring a healthy chunk of the emissions reduction load onto the backs of the newly developing but still far from wealthy BASIC nations.

China and India wanted to make sure that there was no way that the toothless Copenhagen goals could be presented as a substitute for the legally-binding Kyoto Treaty (with its advantageous free pass for developing countries), or used as a justification for unilaterally pressuring the BASIC countries to take matching steps while the Obama administration stood on the sidelines and calculated its political fortunes in the U.S. Senate.

Unsurprisingly, the Chinese delegation, with India’s support, took the lead in stripping the Copenhagen agreement of anything—including the emissions cuts commitments by the EU, Japan and others– that could allow it to be construed as a successor to Kyoto.

As Environment Minister Ramesh reported to the Indian parliament on December 22 India has come out quite well in Copenhagen: Ramesh (Lead):

“India, South Africa, Brazil, China and other developing countries were entirely successful in ensuring there was no violation of the BAP [Bali Action Plan] (of 2007),” Ramesh said.

“Despite relentless attempts made by developed countries, the conference succeeded in continuing negotiations under the Kyoto Protocol for the post-2012 period”, when the current period of the protocol runs out.

To a certain extent, the Western tactics did expose an embarrassing divergence between China’s emphasis on its “right to development” (and to increase its emissions in absolute terms while reducing the per capita “intensity”) and demands by smaller and vulnerable nations for a highly restrictive cap of 1.5 degree C temperature rise and a commitment by the supereconomies of the developing world—and not just the Annex 1 developed countries—to binding emissions targets.

In a Copenhagen post-mortem obtained by Britain’s The Guardian, a Chinese environmental group glumly concluded:

“A conspiracy by developed nations to divide the camp of developing nations [was] a success,” it said, citing the Small Island States’ demand that the Basic group of nations – Brazil, South Africa, India, China – impose mandatory emission reductions.

The true nature of the split was not necessarily between the developing nations and BASIC; it was between those developing nations, led by Tuvalu, that sought to advance their goals in alliance with progressive governments and forces in the West—let’s call them the idealists—and those developing nations, led by Sudan, that decided to make common cause with China and India in pressuring the West—the realists, shall we say.

Pro-Tuvalu Demonstration

Both China and India chose to characterise Tuvalu—the tiny Polynesian nation that started the ruckus by demanding that the developing nations also submit to legally binding caps—as a proxy for the West charged with providing a veneer of third-world credibility to efforts to shift emissions burdens away from the developed world.

Indeed, Tuvalu is closely allied to Australia. Its climate change negotiator, Ian Fry, is on the faculty of Australian National University’s law school—he resides in Australia, not Tuvalu, a fact that his critics used to score political capital—and also acts as the spokesman for the nettlesome Alliance of Small Island States that the Chinese report referenced.

Tuvalu threw its weight behind a proposal that appeared technically unfeasible—demanding an actual reduction in current levels of atmospheric CO2 to 350 ppm (something that modern science has yet to figure out how to do) while prohibiting the use of nuclear and large-scale hydropower.

When China, India, and the oil producing countries responded negatively, Tuvalu staged a walkout, giving the West useful anti-Chinese talking points and reinforcing China’s suspicion that Tuvalu was just there to make life difficult for Beijing.

However, Tuvalu’s draft had been tabled with the UNFCC six months earlier and seems to have reflected environmental optimism that the developed world would go to Copenhagen and display the shared determination to devote hundreds of billions of dollars in a moral crusade to preserve the low-lying real estate of Tuvalu (26 square km; maximum elevation 4.5 meters above sea level; population 12,000), other island nations, and vulnerable and impoverished states in Africa.

By the time of the Copenhagen climate summit, the Obama administration was unable to provide meaningful leadership in committing to a reduction of emissions and the idealists were left without an effective partner.

By end-December 2009, the idealist climate-change agenda was in a shambles and environmentalist finger-pointing had come full circle. Tuvalu turned on Australia for pressuring it to back off on its 1.5 degree Celsius demands and accept a 2 degree rise (which might doom Tuvalu) so that the conference could be closed with a meaningless but face-saving agreement.

It would appear that the group of nations that allied with China and spoke through Sudan felt a greater sense of vindication for their stance. They concentrated on the issue of preserving Kyoto and keeping the onus on the United States to make legally-binding commitments on emissions before leaning on the developing world.

Certainly, the takeaway at the end of the conference for idealists and realists alike was the awareness that the West was not ready to lead on climate change.

In the Western press, Sudan was scorned as a stalking horse for China. However, it gave voice to widespread feelings among G77 countries.

Bernarditas De Castro Muller, a Filipina, was Sudan’s negotiator. Her circumstances illustrate the West’s heavy-handed and counterproductive approach to the nations it was trying to wean from China.

In the runup to Copenhagen, an environmental website, Eco Factory reported:

…the Philippines dropped their chief climate negotiator, Bernarditas de Castro Muller, who was one of the most aggressive and outspoken advocates for emissions reductions in the entire G77 plus China group. De Castro Muller was promptly brought on by the Sudanese government as their new negotiator. There is speculation that the United States and European Union pressured the Philippines to drop De Castro due to her work in unifying developing nations to demand action from industrial countries. Known as the “enforcer” and “dragon woman,” de Castro Muller is expected to demand that most or all of the proposed emissions cuts come from developed nations, and that developing countries should receive billions in aid annually.

When the bastardized final agreement was force fed to the plenary meeting on the last day, the sense of Western discomfiture, disconnect, and arrogance was palpable. In the Guardian, de Castro Muller described how the final deal was pushed through the plenary session in a maelstrom of confusion and resentment:

The final plenary, which all members from all parties must attend, broke out in confusion when the Danish prime minister and conference chairman, Lars Løkke Rasmussen, marched in after making the delegations wait for nearly five hours without any explanation. He took the microphone to announce that a deal (the Copenhagen accord) was done, and secretariat personnel frantically distributed the text. Countries had just an hour to read the text and come up with their positions.

Rasmussen then closed the session without following normal procedures of soliciting views of parties and proceeded to march out again, leaving pandemonium on the floor. The only way to be allowed to speak in the subsequent debate was to ask for points of order, which were not heeded until delegates began banging name-plates on the table. During the interventions, the chairman looked on, glaring at the proceedings, turning now and then to consult the secretariat. No courtesy nor proper attention were accorded to the speakers. The claim that only three or four countries spoke against the accord is false.

Rather thickheadedly, the UK apparently believed that it had won the moral high ground by the intervention of its climate and energy secretary, Edward Miliband, to whip the sullen plenary session into shape by touting the $30 billion in fast-start economic aid and dismissing the comments of G77 spokesman Sudan:

Miliband returned to the conference centre in time to hear Sudanese delegate Lumumba Di-Aping comparing the proposed agreement to the Holocaust. He said the deal “asked Africa to sign a suicide pact, an incineration pact, in order to maintain the economic dominance of a few countries”. A furious Miliband intervened and dismissed Di-Aping’s claims as “disgusting”.

To add a note of genuine farce to the proceedings and punctuate their futility, the plenary session ended with a resounding ovation for a speech by the president of oil-pumping Venezuela, Hugo Chavez, proposing world socialist revolution as the solution to the climate change crisis.

According to the report on an Australian eco-website:

[After Australia’s climate change minister had been interrupted with “jeers and chants”] … Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez received “a standing ovation” for his call for system change to stop climate change. “Socialism … that’s the way to save the planet, capitalism is the road to hell … let’s fight against capitalism and make it obey us”, he said.

Now, all that remains of Copenhagen beyond the brave words and fluttering papers is the “the clever trap”—the Obama administration’s well-advertised promise to deliver billions in immediate climate adaptation relief to the desperate countries of the world, an offer which, by the end of the conference, Tuvalu likened to the 30 pieces of silver that Judas received to betray Jesus.

Concerning the infamous pledge, Sudan’s negotiator, Bernarditas de Castro Muller noted cynically but presciently:

It is sad to say but pledges of financing have a way of evaporating over time, and financing done through existing institutions are unpredictable, difficult to access, conditional and selective.

Fast forward to February 1, 2010 and AFP’s Marlowe Hood reports:

But more than a month after the nearly scuttled climate deal, rich nations have yet to say when and how they will deliver emergency funds to help poor ones begin to green their economies and cope with climate impacts….

The accord also commits developed countries to paying out 10 billion dollars per year to developing nations over the next three years, to be ramped up to 100 billion dollars annually by 2020.

“But it remains far from clear where the funding will come from, if it is genuinely new and additional, and how it will be allocated,” said Saleemul Huq, a researcher at the International Institute for Environment and Development in London.

Many of the poor nations most vulnerable to climate change complained of being sidelined in Copenhagen, and delays in providing the financing could increase tensions as talks proceed, he suggested.

Japan has taken the lead in promising some 15 billion dollars over the next three years, while the European Union has said it will stump up 10 billion.

The United States has yet to announce what share of the 30 billion it will shoulder, but analysts say it is likely to be substantially less, in the 3.5 to 4.5 billion range.

The 3.8 trillion dollar budget unveiled Monday in Washington is thought to contain provisions for 2011.

But so far none of this money has materialised.

“Looking at past experience of overseas development aid and climate funding, it may take several years to disburse even the ‘fast-start’ finance promised for 2010 to 2012,” Huq said.

Then, in New Delhi in January, it was payback time for China and India for the humiliation and frustration of Copenhagen. The BASIC meeting in New Delhi emphasized that the Copenhagen Accord, a “political agreement”, was no substitute for the two track process immortalized as the “Bali Action Plan”, an effort to extend and enlarge the binding legal commitments of the Kyoto Treaty.

In acronym-speak:

The Ministers underscored the centrality of the UNFCCC process and the decision of the Parties to carry forward the negotiations on the two tracks of Ad hoc Working Group on Long-term Cooperative Action (AWG-LCA) under the Convention and the Ad hoc Working Group on further emission reduction commitments for Annex I Parties under the Kyoto Protocol (AWG-KP) in 2010.

The BASIC statement pointedly demanded that the West make good on its promise asap of $10 billion of aid in 2010—a political and financial stretch for the Western powers struggling to distance themselves from the toxic fallout of Copenhagen.

BASIC went the extra mile in turning the tables on the United States. The Brazilian representative in New Delhi indicated that BASIC will set up its own fund to assist imperiled small and island countries at its next meeting in South Africa in April 2010.

Given China’s deep pockets, streamlined foreign aid and finance mechanisms, and desire to embarrass the United States, it is quite possible that BASIC will come up with the money while the West dithers–and it will be the United States and not China that suffers the public relations damage.

In New Delhi, the BASIC countries also announced they were submitting goals to the UNFCCC for reduction of “energy intensity”—energy per capita, their preferred metric, instead of the reduction in absolute emissions they consider unattainable—to show they were not obstructionists.

Brazil, a relatively quiet member of BASIC, used the opportunity to put the boot in with some rather cutting remarks:

“This should be a slap in the face of the developed countries. Frustration comes from Copenhagen as the rich countries did not come up with cuts, but we will not cry about that,” pointed out Brazil’s Environment Minister Carlos Minc.

China has also decided to test its geopolitical muscle by agitating for a greater voice in the creation of the massive IPCC reports that underpin climate change negotiation.

China’s lead climate negotiator, Xie Zhenhua, received some attention for his statement at the BASIC conference observing that there were different viewpoints on the causes of global warming, including the idea that it might be caused by long-term climactic cycles, and it was good to have “an open mind”. This was not a casual statement by Xie—China’s media has shown a growing tolerance for climate change skepticism.

However, it was not a denial of the anthropogenic (human-caused) nature of global warming; the reality of anthropogenic global warming, the central role of Western industrialization in the creation of the greenhouse gas problem, and the subsequent Western responsibility for mitigation are central to the concept of “differentiated responsibility” that China and India use to minimize their own obligations—and serve as the basis for demanding that the West give the vulnerable nations billions of dollars to counter the effects of climate change.

Instead, Xie meant to take advantage of the concerted attacks on the IPCC’s scientific credentials by climate change skeptics in order to assert the propriety of a larger role for the BASIC countries in evaluating the science of climate change, as they already do in the political negotiations, instead of accepting the dominance of Western scientists and their governments in defining the scientific agenda.

Xie’s view was one that Jairam Ramesh—who had endured the IPCC’s slurs of “voodoo science” for his ultimately vindicated view on the stability of the Himalayan glaciers—was happy to second.

In an interview on January 19, Ramesh also called attention to other instances in which he claimed Indian science had been disrespected in the service of Western climate change alarmism:

“In 1990, US raised a scare that methane emissions (an intense greenhouse gas) from wet paddy fields in India were as high as 38 million tonnes. It was later found by Indian scientists and globally accepted that it was as low as 2-6 million tonnes,” Ramesh said.

Again in 2000, just before crucial negotiations, US and other industrialised countries flogged an unverified report of UNEP that claimed soot from chullahs (earthen cookstoves) was adding greatly to climate change, calling it the Asian Brown Haze.

The BASIC communiqué also raised the specter of the group’s emergence as a dominant bloc for negotiating and implementing climate change policy, both on their own behalf and as spokesmen for the G77 nations:

They agreed to coordinate their positions closely as part of climate change discussions in other forums. They emphasised the importance of working closely with other members of Group of -77 & China in order to ensure an ambitious and equitable outcomes in Mexico through a transparent process.

The Ministers also emphasised that BASIC is not just a forum for negotiation coordination, but also a forum for cooperative actions on mitigation and adaptation.

Beyond the creation of an intimidating bloc of rising economies opposed to Western dictation on climate matters, Copenhagen’s primary legacy looks to be little more than anger, distrust, and disappointment. Perhaps it will be remembered as America’s final, failed effort to claim leadership of a great and necessary multinational effort by virtue of its financial and scientific might and moral example.

Certainly, the prospects for President Obama creating a multinational miracle of creativity, determination, and shared sacrifice to rescue the world from the threat of global warming are dimming.

Reeling from the loss of its supermajority in the Senate following the victory of Republican Scott Brown in a by-election for Ted Kennedy’s old seat—and anticipating a further drubbing in the Fall 2010 congressional elections—the Obama administration is paring back its legislative goals, including the Waxman-Markey energy bill.

In order to pass his energy bill, President Obama appears ready to throw cap-and-trade under the bus. On February 2, he stated:

“The most controversial aspects of the energy debate that we’ve been having: the House passed an energy bill and people complained that, ‘Well, there’s this cap-and-trade thing,'” Obama told the crowd.

“We may be able to separate these things out. And it’s conceivable that that’s where the Senate ends up,” he continued.

The leading U.S. progressive political website, TPM, reported Obama’s remarks with the terse obituary entitled Stick A Fork In Cap-and-Trade.

At a town hall style event in New Hampshire a short time ago, President Obama acknowledged that cap and trade might have to be cleaved from the energy bill in the Senate and passed separately, which is to say, not passed at all. (source)

No cap on U.S. emissions probably means no binding climate change treaty—ever.

If the $10 billion does materialize, it is simply a down payment to enable the doomed Copenhagen process to continue so long as it suits the political interests of the participants.

After Copenhagen. Where to from here?

Eric Johnston

In about 10 months, delegates to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change will pack their bags for Mexico City, and the next meeting of the Convention of the Parties (COP). Just six months ago, the Mexico City gathering was considered a pro forma meeting where delegates would spend time tweaking relatively minor issues related to the major issues that were supposed to be settled at Copenhagen. Even on the eve of the Copenhagen summit, when it was clear no legally binding agreement would be reached, optimists in the UN and NGO communities still held out hope that a basic understanding would be reached on issues that had divided delegates since 2007, when, at Bali, the world agreed to come up with a new series of commitments for reducing greenhouse gases beyond 2012. In 2010, the optimists hoped, various lower level UN meetings would meet to work out the details of a few fundamentals agreed to at Copenhagen and a basic treaty would be concluded by early summer. At Mexico City, they hoped to iron out the details. None of that is likely to come to pass, for reasons that Peter Lee so painstakingly details. As dispirited and angry delegates and participants headed out of Copenhagen’s Bella Center conference hall for the last time to catch their planes home on a cold Saturday morning two weeks after the conference began, and following the all-night marathon negotiating session that ended in the weak and heavily criticized Copenhagen Accord, the question on everyone’s lips was “What now?”

Yvo de Boer, the head of the UNFCCC, told journalists at the final press conference that he could not imagine 120 world leaders gathering again in Mexico City. Over the past month or so, those hoping for a scientifically valid agreement anytime soon must surely have been disappointed at the headlines, which indicate that few countries are prepared to formally register their commitments in the Copenhagen Accord. In the U.S., polls show growing numbers of Americans either doubt climate change science or question whether the human race has much to do with whatever change is occurring. Questions at Copenhagen of whether or not President Obama had the will and wanted to spend the domestic political capital with his Congressional opponents necessary to even finish the deal at Mexico City, let alone lead the world to a treaty based on the science, have turned into deep pessimism.

Jonathan Pershing, one of the top U.S. negotiators at Copenhagen, indicated in January that the U.S. would be open to some sort of new negotiation forum with countries like China. But the U.S. refusal to commit to the reduction targets the Bali agreement recommends for developed nations, combined with China’s continued insistence that developed nations adhere to Bali and its refusal to agree to place its “voluntary” domestic reduction targets announced last November in an international treaty precisely because they don’t have to under the Bali agreement has created a stalemate that shows no sign of being broken. It is possible Japan could play a role in helping bring the two sides together, assuming that (1) both Japanese Prime Minister Hatoyama Yukio and Obama want Japan to play a role, and (2) assuming the problems currently plaguing the U.S.-Japan relationship (the Futenma base relocation issue, the problems with Toyota) can be resolved or at least set aside at the top levels of both governments in favor of working on climate change. It also assumes Japan is willing to take the lead in a highly visible way, something that was certainly not on display at Copenhagen. For despite being the only major industrialized country outside the European Union to (more or less) commit to greenhouse gas reductions in line with UN targets (25 percent reduction by 2020, based on 1990 levels) and despite the fact that Japan pledged to provide nearly half of the 30 billion dollars the UN requested for start-up funding for mitigating climate change in developing countries, Japan had an extremely low profile at COP15. While the U.S., the EU, and China had open and inviting delegation booths that all delegates, visitors, press and NGOs could easily access, the Japanese delegation was shut away in a windowless office, whose closed doors merely boasted signs promoting the “Welcome to Japan” tourism campaign. Whereas the U.S., the EU, China, India, the Group of 77, Indonesia, Brazil, and Bangladesh held regular, open press briefings to all media in a large, quiet room with proper sound and lighting, the Japanese delegation provided kisha club (Press Club)-only briefings around a small, cramped table in the back of their partitioned-off, extremely noisy delegation office. The first open press conference by Japan was finally held just four days before the end when Environment Minister Ozawa Sakihito arrived in Copenhagen with the 15 billion dollar total pledge in hand.

This low profile is in contrast with the fact that when people in the conference hall did speak of Japan, it was in a positive tone of voice. In comments to The Japan Times, U.S. Senator John Kerry praised Japan’s financial contribution, while NGOs like Greenpeace generally saw Japan’s influence as a quiet, but positive, one. Whether or not such positive international reviews of its climate change policies under Hatoyama, especially in the face of sustained opposition by major Japanese utility, steel, and auto companies who warn of high costs to consumers and job losses, will translate into international leadership on climate change in the form of bringing the U.S. and China back together on the issue remains to be seen. But there will be two major opportunities in 2010 to demonstrate such leadership.

Japan is due to host a major UN conference on biodiversity preservation in Nagoya this October (link), a conference that is supposed to agree on new ways to preserve biodiversity in the coming years. It will be attended by numerous UN representatives involved in climate change, as the two are closely linked, although far fewer delegates are expected than attended Cop15. A few weeks later, Japan will host the Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) forum, where the leaders of not only the U.S. and China, but also India and Indonesia will be in attendance, and where dealing with climate change will be one of the issues leaders will surely want to discuss. But given the disaster, in the words of the Swedish Prime Minister, that was Copenhagen, given questions, valid or not, raised about the IPCC’s integrity, and given that a growing number of voices in government, NGOs, and the media wonder if it isn’t time to rethink the basic structure of UN climate change treaty negotiations, climate change is lower on the international political radar than it was just a few short months ago. Negotiations to get things back on track, de Boer admitted at the very end of the Copenhagen conference, are likely to be very long and very complex, with no guarantee the momentum can be regained. Some UN delegates leaving Copenhagen as the meeting closed remarked to the press that perhaps the warmth and sunshine of Mexico would be more conducive to an agreement than dark, cold Copenhagen. But as Lee demonstrates, given the breakdown at the end and the fundamental differences that led to that breakdown, the domestic political realities and fundamental differences in views over numbers, be they scientific or financial, the forecast at the moment for a new agreement by Mexico City that is both scientifically valid and politically acceptable is extremely cold and cloudy, with political thunderstorms likely.

Peter Lee is the moving force behind the Asian affairs website China Matters which provides continuing critical updates on China and Asia-Pacific policies. His work frequently appears at Asia Times. He wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Eric Johnston is Deputy Editor for The Japan Times and a Japan Focus associate. He covered the Copenhagen conference and wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: Peter Lee and Eric Johnston, “The Copenhagen Challenge: China, India, Brazil and South Africa at the Barricades,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 8-4-10, February 22, 2010.