Eric Johnston

Eight years ago, on the eve of the 2000 U.S. presidential election, a bipartisan group of Washington experts released the Armitage Report, named after Richard Armitage, one of the main authors and an eventual deputy secretary of state under President George W. Bush.

The report warned that America and Japan had drifted apart during the years of Bill Clinton’s presidency and urged a stronger military and security partnership.

Now, on the eve of the 2008 presidential election, advisers to Republican nominee Sen. John McCain and Democratic candidate Sen. Barack Obama are once again calling for a re-engagement with Japan, an admission that the relationship has problems.

Meanwhile, independent experts note the Bush years strengthened U.S.-Japan military relations but warn a lack of deep bilateral political ties and the global financial crisis will make it difficult for whoever ends up as president to forge a broader relationship with Japan.

At the National Press Club in Washington, D.C., in September, McCain and Obama’s main Asia advisers outlined how their candidates viewed the Japan-U.S. relationship and U.S.-Asian policy.

Obama’s advisers emphasized he saw security relations with Japan in the context of larger global issues, while McCain’s advisers said their candidate would strengthen the alliance in areas like dealing with Japan’s Asian neighbors.

“Obama believes the alliance with Japan is the cornerstone of U.S. security policy in the Pacific. Not only to focus on the challenges of East Asia, especially North Korea and the rise of China, but also on a global basis, on climate change, on peace operations in the Middle East, on economic development, and on democracy promotion,” said Frank Jannuzi, former East Asia regional political and military analyst for the U.S. State Department and Asia specialist for the Democratic staff of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

McCain campaign adviser Michael Green, senior adviser and Japan chairman at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, said McCain was sensitive to Japanese public and political opinion regarding North Korea.

“Our Japanese friends worry we’re not tending to real security issues that concern our allies. One of those is North Korea. McCain said he would not support lifting sanctions without progress in the abductees, without verification,” Green said.

Despite reassurances from both the Obama and McCain sides, however, the 2008 election campaign has produced comparatively little discussion on Japan, unlike the months prior to the 2000 election.

Both Obama and McCain have spoken at length about America’s future relations with China, both in the context of East Asian security, and especially regarding America’s trade deficit with China.

Japan and North Korea

Now that the Bush administration has announced it was lifting sanctions on Pyongyang, the next president will face the task of reassuring a disappointed Japan that it will keep the pressure on North Korea over the issue of Japanese nationals abducted by Pyongyang in the 1970s and ’80s.

And the way the Bush administration handled the situation is likely to be remembered in Tokyo if the new U.S. president seeks further Japanese military cooperation.

“The fact that it was only 30 minutes before the official announcement (of the delisting) that U.S. President George W. Bush actually picked up the phone to notify Japanese Prime Minister Taro Aso reminds me of how Richard Nixon let Prime Minister Sato Eisaku know about his visit to Beijing 37 years ago, where the latter notification was made only three minutes before the official announcement,” said Murata Koji, a political science professor at Doshisha University, in an Op-Ed article this week for The Association of Japanese Institutes of Strategic Studies.

“Donor countries have already pledged $20 billion in aid to Afghanistan. Given that many of the countries providing troops there are suffering from the financial crisis, Japan may well face a request for further economic assistance. Such a development could result in a deeper sense of abandonment among the Japanese over America’s North Korea policy on the one hand, and heightened fear that they have become “entrapped” in America’s global strategy on the other,” Murata added.

A McCain presidency would also mean continued U.S. pressure on Japan to contribute more to the bilateral defense and security relationship.

“McCain would encourage Japan to keep moving on the path of playing a larger role, including U.N. Security Council membership, where there is bipartisan support for Japan’s membership,” Green said.

Economic Relations and Nuclear Power

On economic relations, one area where Obama and McCain may strongly differ is the need for a Japan-U.S. free-trade agreement.

Business groups in both countries have voiced their support for such an agreement, but U.S. access to Japan’s agricultural markets remains a sticking point. McCain, his advisers say, would likely push harder for an agreement, while Obama’s advisers would have strong reservations and concerns about the effect on U.S. jobs.

The presidential candidates also differ on an issue getting little media attention: expanded bilateral nuclear power cooperation. During their second televised debate, McCain, a strong advocate of nuclear power, praised Japan and South Korea as countries with advanced nuclear power technologies that could help build 45 new nuclear plants in the U.S.

Obama is decidedly less enthusiastic about nuclear power and more interested in developing other energy technologies.

In speeches before he became a candidate, Obama praised Japanese automakers for developing fuel-efficient cars using clean and green technologies, and suggested there is much to learn from Japan in this regard.

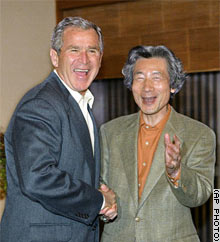

The Bush-Koizumi Relationship and the Future

While there is a perception in Washington that the Bush- Koizumi period was something of a golden era for U.S.-Japan relations, a growing number of policy experts on both sides of the Pacific warn the underlying political relationship is weak and there may be problems getting things done no matter who becomes president.

“The degree of U.S.-Japan cooperation under the Bush administration has been, to some extent, overrated. The alliance was strengthened during the Bush-Koizumi years, but the political base of the alliance was not broadened. That’s what the next administration should work on,” said Kent Calder, director of the Japan studies program at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies and a former special adviser to the U.S. ambassador to Japan, at a press briefing in Tokyo in August.

The new U.S. president will also have to deal with a Japan that could soon have a new prime minister and perhaps a new, Democratic Party of Japan-led government.

Here, the lack of political depth and connections between the Democratic Party in the U.S. and the DPJ could pose problems for U.S.-Japan security relations on issues ranging from the dispatch of Japanese forces abroad for missions without a United Nations mandate, which the DPJ opposes, to the reorganization of U.S. bases in Japan, an issue now stalled due to opposition in Okinawa over the Futenma replacement facility.

“The U.S. Democratic Party and the Japanese DPJ are unknown, or misunderstood, quantities in the other country. Late last year, Japan finally realized it had to take the possibility of a Democratic administration in the U.S. seriously. The U.S., on the other hand, is only reluctantly now getting around to that realization it may have to deal with the DPJ,” said Robert Eldridge, associate professor at Osaka University’s School of International Public Policy.

Eric Johnston is a staff writer for the Japan Times and a Japan Focus associate. This article was published at The Japan Times on November 1, 2008 and at Japan Focus on November 1, 2008.

He can be reached at [email protected]