This article is the second in a three-part symposium. See parts one and three.

Contentious debates between historians who investigate and document the Imperial Japanese military’s active involvement in the establishment, maintenance, and operation of its system of enforced prostitution and those who seek to simultaneously refute and justify it have been ongoing since the mid-1990s. But Japanese far-right historical revisionists are now making concerted efforts to mobilize Japanese communities in the U.S. in an effort to induce sufficient doubt concerning the accepted historical knowledge of the WWII-era Japanese military “comfort women” to paralyze international efforts to hold the Japanese government accountable.

The existence of Japanese “comfort women” revisionism in the U.S. first came to light when former University of Southern California business professor Koichi Mera and his group, Global Alliance for Historical Truth (GAHT), filed a lawsuit in early 2014 against the City of Glendale, California to force the removal of the city’s “peace memorial” dedicated to the victims of Japan’s “comfort women” system. Mera and his co-plaintiffs lost both state and federal cases and are currently appealing.

In addition to Mera and other Japanese nationals and first-generation Japanese immigrants (shin issei) who live in the greater Los Angeles area, GAHT has enlisted prominent conservative activists and pundits from Japan as its board members, including Fujioka Nobukatsu, a founder of the Japanese Society for History Textbook Reform (Atarashii Rekishi Kyoukasho wo Tsukuru Kai), and Yamamoto Yumiko, the president of the “comfort women” revisionist group Nadeshiko Action and a former vice president and secretary general for Zaitokukai, a notorious anti-Korean hate group in Japan.

The convergence of far-right historical revisionists from Japan and the U.S. is not accidental: Japanese conservatives have argued for several years that the U.S. was going to be the “shusenjo,” the main battleground, in the “history war” they were fighting.

One of the first conservative activists to voice this perspective was Okamoto Akiko, in the May 2012 issue of Seiron, a conservative opinion magazine. There, Okamoto, who at the time headed the Family Values Society of Japan (Kazoku no Kizuna wo Mamoru Kai), confesses that she had assumed that the “comfort women” controversy had already been “won”-that is, she had believed that conservatives had already successfully proved that the whole “comfort women” issue was based on fabrication, and that the voices calling for justice for its victims (or “victims,” in her mind) were in their last throes.1

The construction of a “comfort women” memorial in Palisades Park, New Jersey in 2010 and proposals to erect similar memorials elsewhere in the United States (including Glendale) took Okamoto by surprise, and led her to re-evaluate the situation. She quickly realized that while conservatives continued to increase their domination of the Japanese political discourse surrounding “comfort women,” they were losing ground in the U.S. and in the United Nations.

Okamoto’s call to respond to criticisms against Japan’s history of “comfort women” is echoed by the conservative media and activists, so much that “the U.S. is the ‘shusenjō'” has now become a familiar slogan among Japanese conservatives, who call on the Japanese government to more forcefully promote “Japan’s side” of the “comfort women” controversy in the U.S.

Since the filing of the Glendale lawsuit, there have been several lectures and panel discussions by Japanese “comfort women” revisionists in the U.S. For example, in December 2014 Yamamoto Yumiko along with fellow revisionists Mera of GAHT, Fujii Mitsuhiko of Rompa Project (connected with the Japanese religious group, Happy Science), and others gave lectures in San Francisco and Los Angeles. In March 2015, Yamamoto, Mera, Fujii, and others held a series of events in New York City during the meeting of the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women. The U.S. branches of the nationalist Happy Science arranged the logistics for these events. In addition, there have been many smaller events in Los Angeles that centered on combating the “myth” of “comfort women.”

It should be noted that these events have specifically targeted Japanese nationals and “shin issei” immigrants residing in the U.S., not Japanese Americans. In fact, they are usually only promoted in Japanese-language media and conducted exclusively in Japanese without English interpretation. Even U.S.-based Japanese revisionist groups (such as GAHT) operate their websites in the Japanese language only. The goal of this approach appears to be twofold: first, it mobilizes Japanese residents in the U.S. to organize among themselves to influence the larger U.S. discourse; second, it shows their supporters in Japan that they are gaining ground.

Local Japanese American groups such as Nikkei for Civil Rights and Redress, the San Fernando Valley chapter of the Japanese American Citizens League, and the Japanese American Bar Association of California have joined Korean American and other Asian American communities in support of the memorials honoring the former “comfort women” and explicitly oppose “comfort women” revisionism.

Against this background, the announcement of a film screening and lecture to be held at Central Washington University in April 2015 was notable as the first Japanese “comfort women” revisionist event to be held in English primarily for a non-Japanese audience. It was also notable, unfortunately, as the first instance of a university campus allowing itself to be used as a platform for promoting the dishonest and bigoted narrative that is “comfort women” revisionism.

In the summer of 2014, I co-founded the Japan-U.S. Feminist Network for Decolonization (FeND) with other U.S.-based Japanese and Japanese American individuals to counter the mobilization of Japanese “comfort women” revisionism in the U.S. and to challenge both Japanese and U.S. colonialisms. Since our founding, we have worked with activists in other cities to protest revisionist events in San Francisco and New York City. Based in Seattle, I had not had the opportunity to be present at these protests until the Central Washington University event.

As they learned of the revisionist program, students, staff, and scholars at Central Washington University came together to organize an alternative event. Because of such overwhelming response from within the campus community, we members of FeND and the Seattle-based progressive Japanese American group Tadaima decided to bring copies of our handouts and booklets and support the alternative panel rather than organizing something on our own.

The CWU event was a civil yet firm response to the “comfort women” revisionists who descended on campus, as Mark Auslander and Chong Eun Ahn discuss in detail in a separate report. Hundreds of students and interested community members packed the alternative “academic panel” on the history of the “comfort women,” while barely a dozen or so attended the revisionist event, which took place at roughly the same time in the same building. But we were curious about the content of the revisionist event, so we drove back to Central Washington University the next day to attend day two of the revisionist event (the alternative panel took place only on the first day).

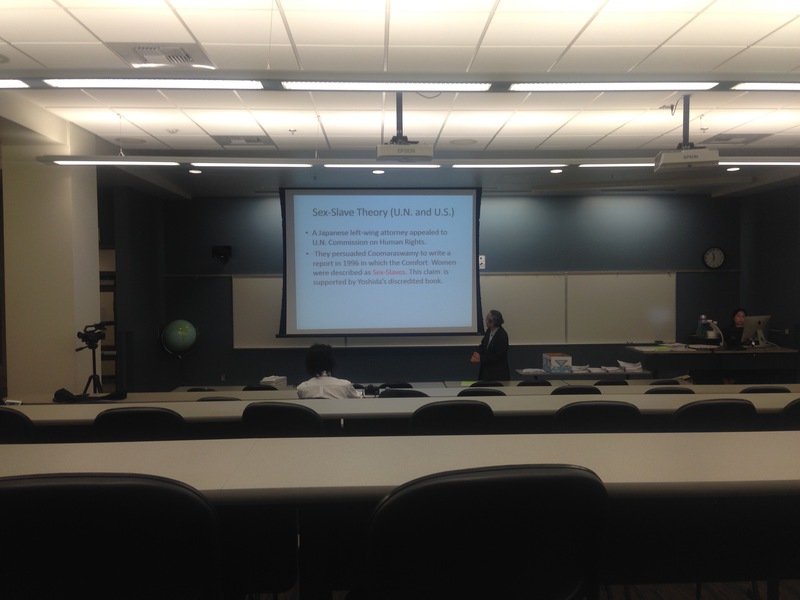

The revisionist event had been organized by Japanese language instructor Mariko Okada-Collins and featured a film and lecture by Taniyama Yujiro, a presentation by Koichi Mera of GAHT, an appearance by University of Wisconsin graduate student Jason Morgan over the internet, and a statement from scholar Chung Daekyun, a naturalized Japanese citizen of Korean descent. Even fewer people showed up on the second day.

Okada-Collins spoke first about how she had come to the topic of “comfort women.” She stated that she was unaware of “comfort women” or the controversy surrounding the topic until 2006, when a political scientist brought a former Korean “comfort woman” to campus. She began studying the issue, acquiring materials from Japan, and came to the conclusion that “comfort women” were “simply prostitutes.” She blasted the U.S. attitude on “comfort women” as “one-sided,” and expressed the need for “all aspects of the issue” to be evaluated, including the revisionist view.

Interestingly, Okada-Collins conceded that some expressions in Taniyama’s film were “offensive” even to her. But she argued that they should be understood as “outbursts of anger” at the “oppression” faced by Japanese people at the hands of Koreans. “His film may be offensive, but he is telling valuable information,” she said.

Following Okada-Collins, Taniyama appeared in a Rising Sun t-shirt and began his talk by acknowledging that Japan was “fighting a losing war on ‘comfort women.'” But he had to tell the truth, he said, because “the truth will set you free,” quoting the Bible.

In mentioning the protesters who stood silently holding signs at his event on the previous day, Taniyama referred to them as “Korean American protesters” despite the fact that he had been informed multiple times that the protesters were members of a Chinese exchange student club. He further stated that the protesters were “a threat to the First Amendment,” comparable to the “insurgency in Baltimore.”

He then discussed at length discrepancies among various survivor testimonies, suggesting that “allegation [against Japan] is wildly false.” He attacked “evangelical feminists” for denying the “truth”: , it was, for instance, Korean brokers who recruited women to be “comfort women,” not the Japanese military. As evidence, he quoted historian and Korea expert Bruce Cumings, who wrote that most recruiters were in fact Koreans but failed to mention that Cumings also wrote that the Japanese largely occupied managerial or supervisory roles, contracting or delegating the actual recruitment to Korean subordinates, and that he is quite critical of Imperial Japan’s use of “comfort women.” He also cited Korean scholars C. Sarah Soh and Byong Jik Ahn, similarly quoting them out of context and consequently distorting their work.

Taniyama then attempted to justify his naming his film, Scottsboro Girls, an obvious reference to the “Scottsboro Boys,” young African American men who were falsely convicted and imprisoned for two decades for the supposed crime of raping white women. “Comfort women issue is not the same, but the same lessons apply,” he said. “This whole issue is based on racial hatred. So much lies, injustices… Comfort women don’t have the right to falsify history. Comfort women issue is an issue of social justice.”

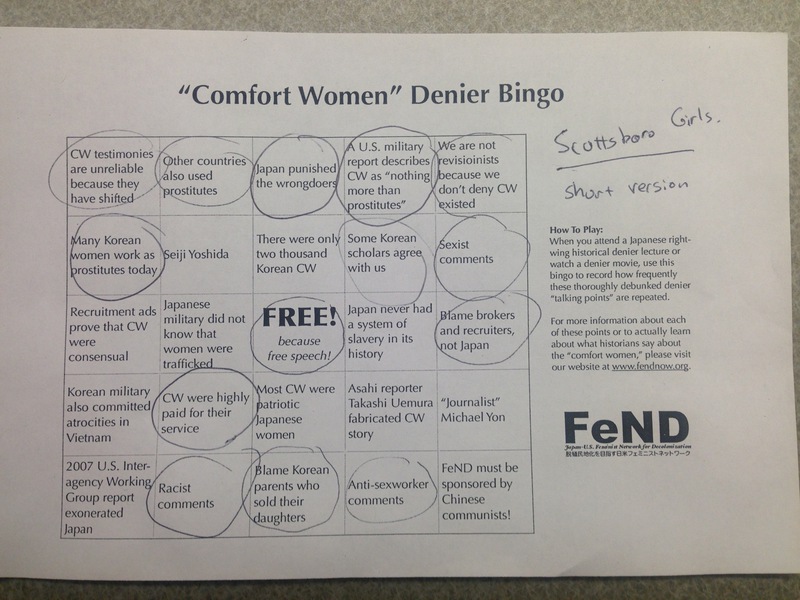

Scottsboro Girls is three-hour long in its full version but Taniyama had edited the film down to 45 minutes for this event. The film repeated familiar revisionist talking points (see “Debunking the Japanese Right-Wing ‘Comfort Women’ Denialism” on FeND’s website, as well as the photo of the completed “Comfort Women Denier Bingo” scorecard below) without providing any new information. It used decontextualized quotes from many sources such as Bruce Cumings, mentioned above, and radical feminist theorist Susan Brownmiller.

|

Completed “‘Comfort Women’ Denier Bingo” scorecard. Photo by the author. |

The film starts off with, Taniyama talking about the sexual abuse allegation against actor and director Woody Allen. “Did Woody Allen actually abuse his seven year old girl? I don’t know. I wasn’t there.” He then applies the same logic to the topic of “comfort women”: “Were these women actually sex slaves? I don’t know; I wasn’t there. And neither were you.” He follows up on this disclaimer with the observation, “Sometimes, people are falsely accused. You could be sued tomorrow by a vengeful ex-girlfriend. Just like Trayvon Martin.”

Taniyama’s lack of sensitivity toward the suffering of child sexual abuse victims and African Americans is telling. His scattershot narrative is also revealing about the political aim of the historical revisionist project. It is not necessarily about proving a point but seeks to obfuscate reality and cast doubt about the historical consensus in the minds of the public. Historical revisionists do not need to win an argument to score a political victory: they win simply by concealing their dishonesty and turning the history of “comfort women” into a historical episode that experts can legitimately disagree about. To this end, they neither introduce new evidence nor re-evaluate existing evidence but cherry-pick what suits them and blend it with political pressure.

Following Taniyama was Jason Morgan, a University of Wisconsin history graduate student who is studying in Japan on a Fulbright. Morgan, who has been heralded by the American conservative media for refusing to take part in diversity trainings that were required of teaching assistants at his university, lambasted political correctness in the American academy throughout his presentation.

Morgan took the position that “documentary evidence is overwhelmingly on our side,” meaning the side denying the Japanese military’s culpability for the “comfort women” system. He criticized the group of twenty historians who had earlier issued a statement against the Japanese government’s attempt to pressure U.S. publisher McGraw Hill to revise its description of “comfort women” in a world history textbook. The twenty historians were “consistently appeal[ing] to emotion” and arguing from authority rather than from facts, he stated.

Morgan argued that American academia used to be more objective and “value-free scholarship” had been the norm, but it had been overrun by political correctness, which deployed words such as “trigger warning” and “microaggression” to stifle academic exchange. “The academy has been completely sanitized of opposing views,” he complained.

Morgan also did not hesitate to make false claims, such as that the former Asahi Shimbun reporter Uemura Takashi “wrote about Seiji Yoshida’s false testimony,” and that all of his reporting about “comfort women” was later retracted. Contrary to Morgan’s claim, Uemura did not write any articles mentioning Yoshida, and he was cleared of any journalistic misconduct by an independent review, despite the right-wing defamation campaign that has led to death threats against his family.

Koichi Mera of GAHT spoke next. Like Taniyama and Morgan, Mera repeated many of the same tropes, blaming Korean Americans for using the “comfort women” issue as “an excellent vehicle to accelerate their disdain against Japanese nationals.”

The written statement from Chun Daekyun did not present any particular claim regarding the “comfort women” controversy but appeared to insist that Koreans are inherently dishonest: ”Now in Korea, almost all beautiful women took plastic surgery. It is quite the same problem in History science field… I warn Japan to be careful to play this history game with Korea.” He accused the government of Korea, not Japan, of historical revisionism, urging CWU students to “understand” “why supporting a government-promoted version of history, on any subject, is dangerous for liberal democracies.”

There were no questions from the audience, which by that time numbered only two or three, excluding FeND members, Japanese reporters, and the presenters. Concluding the event, Mera exclaimed, “I’d congratulate Ms. Okada for this wildly successful event!” without any sign of irony.

After returning to Japan, Taniyama posted that he had met someone in the U.S. whom he described as a “fake feminist,” “old maid,” “self-identified ‘Japanese’,” and “horrifyingly sad,” in a transparent attack on me, despite our having had a cordial interaction after the event.

But Taniyama was outdone by his travel companion Miyake Makoto, a far-right member of the Komae (part of metropolitan Tokyo) city council who referred to me by name on social media and bragged about having refused to exchange business cards with me (as Japanese people conventionally do when they meet each other) because, in his own words, Miyake is “not into homosexuals.” Coming from an elected official in Tokyo, this might seem shocking, but none of his supporters apparently minded.

On each day, I was able to talk to a student who had attended at least part of the right-wing event. Both students told me that they had attended the event out of curiosity but were shocked to see for themselves that there were people who actually held such reprehensible views. I would like to have interviewed more students, but there weren’t many to begin with.

Within days after the CWU event, the conservative daily Sankei Shimbun published a story featuring Morgan as the fresh new voice of “true” American scholarship. But he is not the only such figure: in their “history war” whose “major battleground” has shifted to the United States, conservatives have been busy recruiting barely qualified American “experts” to their side, including video blogger Tony Marano (known as “Texas Daddy” in Japan), writer Michael Yon, and others who are showered with lucrative book deals and speaking tours in Japan for repeating the same revisionist talking points.

A member of FeND who went to the event with me, who was born in Japan but came to the U.S. as a young child, told me that the experience motivated her to become more fluent in Japanese so that she could understand the issue further and fight the Japanese historical revisionists more effectively. My friends in the Seattle Asian American communities are now also interested in learning more about the issue. I myself renewed my commitment to push “comfort women” revisionism out of the U.S.-especially from the Japanese communities in the U.S.-and support people in Japan who continue to fight it there.

Emi Koyama is an activist and writer living in Seattle. She is a co-founder of Japan-U.S. Feminist Network for Decolonization (FeND) http://www.fendnow.org/ and blogs at http://eminism.org/

Recommended citation: Emi Koyama, The U.S. as ‘”Major Battleground” for “Comfort Woman” Revisionism: The Screening of Scottsboro Girls at Central Washington University’, The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 13, Issue 22, No. 2, June 1, 2015.

Notes

1 Okamoto Akiko. “Kankoku no Ianfu Hannichi Senden ga Man-en suru Kozu: Beikoku no Houjin Shitei ga Ijime Higai.” (How South Korea’s “Comfort Woman” Anti-Japanese Advertising Spread Everywhere: Japanese Children in the United States Are Bullied. Seiron, May 2012: 126-133.