Memories of the Dutch East Indies: From Plantation Society to Prisoner of Japan

Elizabeth Van Kampen

Introduction

In 1928, at the age of one and a half years, Elizabeth van Kampen, daughter of a Dutch plantation manager, arrived with her parents in Sumatra in the former Dutch East Indies (today’s Indonesia), a land which she evokes from childhood memory as “paradise on earth.” But the attack on Pearl Harbor of December 7, 1941, when she was fourteen, was quickly followed by Japanese invasion of the Dutch colony and the nightmare to follow.

Elizabeth and her family experienced extraordinary times between two empires, that of Holland in Asia at the end of a 400-year epoch, and that of a rising militarist Japan. The following images convey a sense of a range of experiences of plantation life through the lens of the Dutch planters.

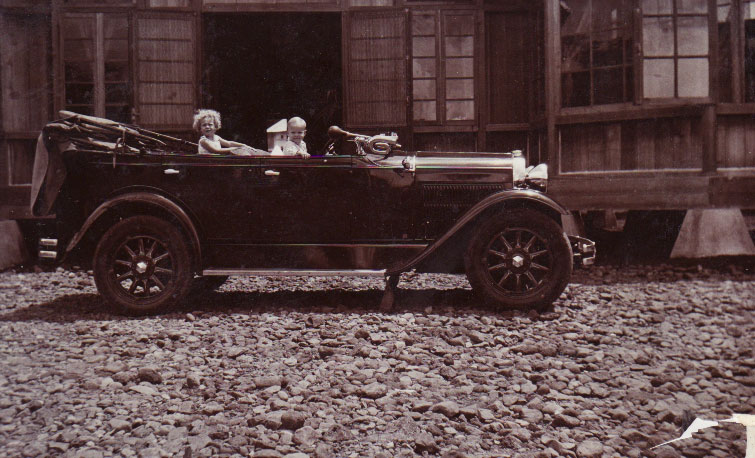

Car of the head of the plantation Subam Ayam, Benculu, 1929.

Elizabeth’s father inspecting coffee seeds.

A home in Elizabeth’s neighborhood. Many houses were built on stilts.

Disinfecting rubber trees on the plantation.

Coffee factory where berries were sorted, dried and roasted.

A young married couple in a plantation wedding.

For the young girl, it was a passage from heaven to hell, but an experience that she faced with the resilience of a spirited youth. With Japan’s capitulation in August 1945, Elizabeth was finally released following a three year incarceration in a prison-gulag from which her beloved father would not return alive.

The abrupt surrender of the Japanese Imperial Army all across occupied Southeast Asia created a power vacuum and hiatus for aspiring Asian nationalists from Vietnam, to Malaya, to Indonesia, even before the return of colonial armies. As witnessed by Elizabeth in the heady post-surrender days, Indonesian nationalists around Sukarno declared independence (August 17, 1945), somewhat incongruously in the Jakarta-house of a Japanese Admiral. Before the arrival of returning British and Dutch forces, Japanese units surrendered arms to the independence forces. In any case, Elizabeth witnessed Indonesian pemuda or pro-independence youth groups, with or without support of Japanese-armed heiho auxiliaries, taking the law into their own hands.

In 2008, at 81 years of age, Elizabeth van Kampen offers a personal reflection on her youthful experiences spanning the years of privilege as a child growing up in Dutch colonial society, those of trauma in a Japanese prison, and the uncertainties of the early Indonesian revolution of 1945. Her remarkable account, written first in Dutch in 2006, is especially instructive for its dispassionate, albeit wistful, eyewitness reportage, one that strives to find good in the midst of adversity and cruelty, as with her account of the “good” Japanese doctor who acted to save her sister’s life and the kind and caring Javanese families who protected her in tumultuous times. She also recounts the inexplicable, as with the frightening human-pig basket story, the heartless separation of boys from mothers in the prison camp, and the larger-than-life grotesqueries of the ubiquitous kempeitai.

Fifty years after the war, Elizabeth returned to the East Java prison sites seeking clues as to her father’s missing grave only to find that the Kempeitai had destroyed all records. She also traveled on to Japan visiting well-wishers and learning that Japanese people too had suffered from militaristic excesses. As elaborated below, she is part of a group that stages periodic demonstrations in front of the Japanese Embassy in the Netherlands seeking official acknowledgment of Japanese war crimes committed in the Dutch East Indies, not only against Dutch but Indonesian people as well.

We offer below excerpts and photographs from a long and layered personal diary, together with Elizabeth’s responses to questions about her experience, whose full text can be read at www.Dutch-East-Indies.com. Additional historical photographs added. Elizabeth’s bilingual English-Indonesian website story continues to evoke interested and sympathetic comment from a variety of audiences in modern-day Indonesia and around the world.

Geoffrey Gunn

The Dutch East Indies is lost forever

On the 10th of January 1942, the Japanese invaded the Dutch East Indies. The newspapers brought us a lot of bad news. My father had long ago advised me to read some of the articles I liked from the Malanger and the Javabode starting since I was almost eleven years old, so now I could read all the bad news in the papers when I was at our Sumber Sewu, plantation home near the East Java city of Malang during the weekends.

Now and then we saw Japanese planes flying over Java. I found it all strange and very unreal. The only Japanese I knew where those living in Malang; they were always very polite and friendly towards us. But from now on Japan was our enemy.

On Saturday the 14th of February 1942, my father came to fetch Henny (my younger sister) and I from our boarding-school for the weekend. We went into town where we did some shopping for my mother and next we went to the Javasche Bank. When my father came out of the bank, we heard and then saw Japanese planes coming over. This time they machine-gunned Malang. I saw two working men, who were hit, falling from the roof where they were busy. They were dead, we saw them lying in their blood on the street. I had never seen dead people before; Henny and I were deeply shocked. Henny started crying, my father took us both quickly away from this very sad sight.

On Sunday the 15th of February we received the bad news over the radio that Singapore had fallen into Japanese hands. Indeed, that was a very sad Sunday. Who had ever thought that Singapore could fall? Were the Japanese so much stronger than the Allies? And then there was the Battle of the Java Sea from 27 February to 1 March 1942. The Dutch warships Ruyter and Java were hit by Japanese torpedoes; they sunk with a huge loss of life. The Allies lost this battle. The 8th of March 1942, the Dutch Army on Java surrendered to the Japanese Army.

The 9th of March, when we were in the recreation-room from our boarding-school while all the girls were looking through the windows into the streets, the Japanese entered Malang. Henny and I stood there together.

They came on bicycles or were just walking. They looked terrible, all with some cloth attached at the back of their caps, they looked very strange to us. This was a type of Japanese we had never seen before. Much later I learnt that many Koreans also served as shock-troops in the Japanese Army.

The nuns went to the chapel to pray for all those living in the Dutch East Indies. But the Dutch East Indies is lost forever.

Dutch a forbidden language

My father found it too dangerous for my mother and youngest sister Jansje to stay with him at Sumber Sewu, because there were still small groups of Australian, English and Dutch military fighting in the mountains in East Java against the Japanese troops, notwithstanding the fact that the Dutch East Indies government and Army had surrendered.

My mother and Jansje came to stay at our boarding school [at Malang], where there were small guest rooms. We all stayed inside the building, only the Indonesians working for the nuns went outside to do the shopping.

A few days later we received the order that all Dutch schools had to be closed down, so several parents came to take their daughters. The school looked empty and abandoned. We all felt very sad, our happy schooldays were over.

Dutch became a strictly forbidden language. Luckily we had a huge library at school so I had lots of books to read in those days.

A few weeks later my father phoned my mother and said that the four of us should return to Sumber Sewu as he had heard that Malang was no longer a safe place for us to stay.

I was really very happy to be back home. Rasmina, our cook, and Pa Min, our gardener, were happy to have my mother back again. There was absolutely nothing to fear on the plantation, the “Indonesians” (actually Javanese and Madurese) on the plantation were nice as ever and we didn’t see any Japanese soldiers around.

Indeed we were safer at Sumber Sewu. Life began to feel like a vacation,

I started walking with my father again and visited the local kampung (village) and since we had no more newspapers to read, I started reading several of my parent’s books.

We received a Japanese flag, together with the order that the flag had to be respected and had to hang in the garden in front of our house.

My father no longer received his salary, just like all the other Dutch, British, Americans and Australians, living in Indonesia. All our bank accounts were blocked; no one was even allowed to touch their own money.

We still had rabbits and eggs to eat, and several vegetables my mother and Pa Min had planted long before the war in the kitchen garden, and we had many fruit trees.

The thought that we might have to leave Sumber Sewu made me feel very sad. To me this plantation was a real paradise on earth, with its pond in front of the house with the two proud banyan trees, the lovely garden my mother and Pa Min had made, the kitchen where Rasmina made so many delicious meals. The sounds early in the morning, and the sounds in the evening were also very special, I can still remember them so well.

Of course we hoped that this Japanese occupation would soon be over. My father had broken the seal of the radio, hoping that he could get some more news from outside Java.

My mother and her three daughters.

Bamboo Baskets

And then one day at the end of October 1942, when my father and I walked back home for lunch, we heard a lot of noise. It was the sound of trucks coming in our direction as we were walking on a main road. So we quickly walked off the road and hid behind some coffee bushes. We saw five trucks coming and we heard people screaming. When the trucks passed we could see and hear everything, especially since we were sitting higher than the road. What we saw came as a real shock to both of us.

We saw that the open truck platforms were loaded with bamboo baskets, a type of basket used to transport pigs. But the bamboo baskets we saw that day were not used for pigs but for men. They were lying crammed in those baskets, all piled up three to four layers of baskets high. This sight shocked us deeply, but the screaming of all those poor men, for help and for water, in English and Dutch, shocked us even more. I heard my father softly saying; “Oh my God?”

We walked home without saying a word. We had just come out of a nightmare. Even today I can still hear the harsh voices of these poor men crying and screaming for help and for water.

At lunch time my father told my mother the whole story — she could hardly believe that people could do such things. She asked who were driving the trucks. My father told her that in each truck he had seen a Japanese driver and another Japanese sitting next to them.

This tragedy that I saw together with my father happened in the mountains of East Java.

It was only much later on the 11th of August in 1990 that I read in the Dutch newspaper, De Telegraaf, that many more people had seen what my father and I witnessed that day in 1942. Other people had seen many of these men transported in bamboo baskets not only in trucks but also in trains. The article said that the men had been pushed into the bamboo baskets, transported, and then, while still in those baskets, thrown into the Java Sea. Most of the men in the bamboo baskets were Australian military.

I have often wondered: Did my father learn what happened to those poor men we saw that day? Did the local people see it as well? I shall never know.

Come! Let’s walk home

It was strange that we didn’t get Japanese military visitors at Sumber Sewu since they went to Wonokerto the head plantation and other plantations as well, and asked many questions there. My parents were of course more than pleased that the Japanese hadn’t visited Sumber Sewu yet.

But then one day in November 1942 my parents received a phone call from the police in nearby Ampelgading. My father had to bring his car to the police station. It was summarily confiscated. Still, he was happy to have my company on this very difficult afternoon. We went by car but– a real humiliation – we had to walk back home.

When my father came back from work, he said that he really hoped that the Americans and Aussies would come soon to rescue us all from this Japanese occupation of Indonesia. Many Dutch civilian men were now interned all over Java, but not only men, as the Japanese had also started to open camps for women with their children as well.

We were still “free” but for how long?

Christmas 1942

My mother did her utmost in the kitchen to prepare a nice Christmas meal. And then at last it was the 25th of December, 1942. It must have been around 12 noon when we started our delicious Christmas meal, sitting there all six happy around the table.

All of a sudden we heard Pa Min calling; “Orang Nippon, orang Nippon.” (lit. Japanese). My father stood up and went to the front door, my mother took little Jansje by her hand and they went to the living room. Cora went to our bedroom with a book; she was very scared. Henny and I stood at the back of the house and so we could see that there were about six or seven Japanese military getting out of two cars. One of them was an officer. Directly approaching my father, he said that his men had received an order to search the house for weapons. My father told him that there were no weapons hidden in the house.

It was our last Christmas as a whole family together. I can still feel the special warmth of that gathering we had that day because, notwithstanding the Japanese military visit, we were still together.

A Japanese soldier outside oil tanks near Jakarta destroyed by Dutch forces in March 1942

Jungle and Indian Ocean

Soon it was the New Year. We had no more Japanese visitors. There were not many Dutch or other Europeans outside of camps. In Malang there was already a camp for men called Marine Camp. And another camp, we were told, called De Wijk, prepared to house women and children. Taking a long, last walk through the rubber plantations and jungle, my father and I beheld the Indian Ocean. My father looked at me and said, “I have to ask you something, you are almost 16 so you are old enough. I want you to look after Mama and your sisters when I have to leave Sumber Sewa. Will you promise me that?” I remonstrated, but he insisted and I agreed.

And so, at the beginning of February 1942, my father received a phone call ordering him to leave our home in Sumber Sewu within six days and report to the Marine Camp in Malang. This would be a fateful separation. By now, most Dutch men were internees.

A Japanese visitor

My 16th birthday passed. We missed Father terribly and it didn’t look as if he were coming home any time soon, although he always wrote us optimistic postcards. My mother was much less optimistic; she was very worried about the future.

One morning in May 1943 my mother received a phone call from Mrs. Sloekers, who told her that she just had a Japanese visitor who was very polite and friendly. The visitor had asked her if she could play the piano, she told him that she couldn’t play well but that Mrs. van Kampen (my mother) played wonderfully. The Japanese gentleman was on his way to our house, she told my mother.

My mother was not pleased at all. She was very angry with Mrs. Sloekers. Cora and I tried to calm her down, because it wouldn’t do us any good to be so angry before our Japanese visitor.

A tall Japanese officer stepped out of his car when his driver opened the door. I can still see him walking up the stairs greeting my mother very politely and saying that he liked her beautiful living room.

Luckily my mother wasn’t angry anymore so she asked him what he would like to drink and I remember that he asked for a lemon juice. While he sat down he looked at us all and asked my mother if we were all four her daughters.

“No,” my mother said, “she (pointing at Cora) is my eldest daughter’s friend staying with us for a while. I have three daughters.”

He then asked my mother if she would mind very much playing something for him on her piano. “Yes, I hope that I may keep my piano, I have had this piano since I was 8 years old,” my mother answered. Our visitor just smiled and my mother started to play as beautifully as always.

While my mother played the piano our Japanese visitor closed his eyes now and then. He really seems to like the way my mother played. But he also looked at Henny several times and that started worrying me. After a while my mother stopped playing and our Japanese visitor stood up and applauded her. He said that she really played very well, and thanked her.

Then he wrote down something in Japanese on a piece of paper and gave it to my mother. He said that he advised her to go to the Lavalette Clinic (that was our hospital in Malang) with Henny. My mother could then hand over his note and they would call for him because he was a doctor working at this hospital. He told my mother that he wanted to examine my sister, as he found her abnormally skinny.

My mother asked when she could come and he told her that he would phone her.

He gave my mother his hand, thanked her again for the lovely music she had played for him, stroked Jansje’s hair, waved good-bye to Henny, Cora and me and left us all astonished, just standing there.

Within a week my mother had a phone-call from the Lavelette Clinic. They told her that Henny had to stay two weeks in the hospital, and that the Japanese doctor, our visitor, had arranged that Henny should get artificial sunlight since he had diagnosed my sister as suffering from rickets in an early stage.

My mother was advised to stay in Malang during these two weeks, and so she did. She also visited my father several times while she was in Malang.

Before Henny left the Lavalette Clinic the doctor spoke one more time with my mother and gave her a small box with all sorts of medicines, such as quinine, aspirin, iodine, and so on. I didn’t know this of course, but she told me that many years after the war, when I once mentioned that I had found our Japanese visitor that day in May 1943 a nice and friendly man.

This kind Japanese doctor has given my sister a chance to get through the war. By giving her those two weeks of treatment and giving my mother a small box with medicines, he most certainly helped us a little when later the Japanese occupation became a real hell on earth. I have often wondered whether the Japanese visitor know what was coming. Did he know that we were going to suffer terribly and that many Dutch children were going to die?

I don’t know his name, but I would like to say: “Thank you Japanese visitor, thank you very much for your help Japanese doctor.”

“De Wijk,” my first internment camp

In early June 1943 my mother received the bad news that we would have to leave Sumber Sewu on the 11th. Even my mother had hoped that the war would be over before we had to leave our home.

The truck that drove us from Sumber Sewu to Malang stopped in front of Welirang Street 43A, a street I knew very well. Our luggage was put on the pavement and my mother, Henny and I brought everything inside.

We received one room for the four of us. It didn’t look too bad in my eyes. Before the war, the house had belonged to the Hooglands. Mr. Hoogland had been sent to a camp in Bandung. We shared this house with several families, occupying all the rooms of Mrs. Hoogland’s pretty home.

It was nice for my mother because now that she had several women around her she could talk with, she was no longer lonely as on the plantation. A good point was that my father also stayed in Malang, not far away from our camp. He was still writing us but we couldn’t see or visit each other.

As for me, I was quite happy to be back in Malang, I had found some of my friends back, but I missed my father and I missed Sumber Sewu where I had felt so free, so happy.

“De Wijk” camp consisted of many houses with barbed wire all around and some sentry-boxes with Japanese or Indonesian soldiers here and there, to take care that we didn’t try to escape. There were about 7,000 women, children and a few men interned in “De Wijk” from Malang. The Japanese called the camp a protection camp against the local people who saw the Dutch as their “musuh” (enemy). The Japanese used lots of propaganda against the Dutch, British, Australians and Americans. It worked, especially among the local Javanese and Madurese youth in Malang.

De Wijk camp was in hands of Japanese civilians, Japanese “economists” as they were called. That meant that there wasn’t too strict a policy towards the Dutch prisoners. But Malang had a very strict and very cruel Kempeitai management. We all knew that we had to stay out of the hands of the infamous Kempeitai. Sometimes we heard the most horrible stories from some of the Eurasians who were still outside the camps. Even the locals were very scared of the Kempeitai. Malang became completely different from the town I previously had known.

In November 1943, my mother had a visitor. He came by bicycle from the “Marine” camp where my father stayed. He told my mother that he was bringing bad news. He had been sent by the military at the marine camp to tell my mother that my father had been taken by the Kempeitai. It seems that my father had hidden weapons and ammunition at Sumber Sewu. This was a nightmare. Would my father have to stay at the Kempeitai prison Lowok Waryu? Were we ever going back to Sumber Sewu? Sadly enough there were many true rumours about how the Kempeitai treated their prisoners.

Welirang Street 43A

My prison in Banyu Biru

There was no more news about my father, no more letters. The complete silence was very frightening. He had written us so many letters while he was in the Marine Camp and most of those letters had been quite optimistic.

Christmas came, New Year came and so it was already 1944, almost two years since I had seen the first Japanese troops walking into Malang. To me it seemed many years ago and while I had felt absolutely safe at Sumber Sewu, I was now beginning to feel quite insecure at Malang because more and more people were transported to other camps.

The rumours were that we would all be transported to Central Java. But since my sister Henny was ill, the four of us could not go until she was better again. Alas, on the 13th of February 1944, we had to leave Malang. We had to pack our luggage and my mother, Henny, Jansje, and I had to stand with many others on a truck while being driven to Malang station.

Invincible Japan. Poster demonstrating Japan’s military strength to Indonesians

Along the roadside many young people called us all sorts of names. They shouted at us that they were happy that the Dutch had been captured by the Japanese. Tears welled up slowly in my eyes and I bowed my head.

This was happening in Malang, the town where I had been to school. Now I had to leave this beautiful mountain town, “my Malang.” I had to leave my wonderful father behind in a Kempeitai prison. I couldn’t stop the tears falling on my cheeks.

Kempeitai in Indonesia

Adieu Daddy, adieu Malang.

At the station, we were pushed into long blinded goods-trains, we had to sit on dirty floors, and there was no toilet either. There was no food and, worse, there was no water to drink. Luckily my mother had taken some bananas and something to drink with her for the four of us. She also had taken a toilet-pot with her and that was a great help for several of us. Little children started crying, especially when the train stood still (sometimes several hours) and that while the sun was shining on the roof; it was unbearable. We didn’t know where we were being brought; we could hardly see anything at all. This horrible journey took more than 24 hours.

It was in the late afternoon of the 14th of February that we arrived at the station of Ambarawa, in Central Java. A transport of 680 Dutch women and children from Malang stepped out of the train, happy to get some fresh air. The Japanese military yelled at us, and that yelling was translated for us by an interpreter. We all had to climb in the trucks, waiting for us outside the station. Everybody panicked about their luggage, my mother too. She hoped to find our four mattresses, so that at least we could sleep well that night. But we didn’t see our luggage at all.

The trucks drove through a beautiful landscape. At least this time we didn’t have to stand as we had to in Malang. We were all dead tired, hungry and thirsty.

When we arrived at Banyu Biru, we saw a place surrounded by very high walls. What could that be? When we walked towards the entrance I read: ROEMAH PENDJARA, which means Prison. My poor mother almost fainted and she said; “Oh my God, oh my God, how horrible!”

Banyu Biru landscape

My prison

The Banyu Biru bed-bugs and other horrors

The gate was opened by a group of shabby looking Indonesian men who were very surprised when they saw all those Dutch women and children. Slowly we walked into the prison, into a new nightmare. It was a very old and very dirty prison. Later, when we lived there with 5,000 women and children, we learned that this prison was built for just 1,000 prisoners.

My mother, Henny, and little sister Jansje and I were brought to ward 14, an empty ward. We were told to wait for our mattresses so we just stood there, tired as we were from our horrible journey.

Thank goodness our trunks arrived, so we found some clean sheets to cover those stinking mattresses. We lay down, Henny, my mother, Jansje and I, the four of us close together. We were very hungry by now and frightened because the Japanese had barred the door of our ward and that had made an elderly lady, Mrs. Schaap cry. She kept saying that her heart was hurting her and that she couldn’t breathe well. We all felt very sorry for her, but we couldn’t help her. She looked so helpless on her mattress, the poor woman.

At last the door was opened and locals, also prisoners, brought us some sort of a soup in a big barrel. Everybody in ward 14 said “good night” to each other but hardly any of us slept that night. The elderly lady was dying, and she kept on crying from pain. She died around 5 o’clock in the morning and was the first dead woman in this prison. It was all so terribly sad, and made a deep impression on Henny and me. I was half asleep when Mrs. Schaap was taken away from our ward.

Another nightmare: everybody in our ward was bitten by thousands of bed-bugs! So we all started killing those bugs and when we went outside the ward while the sun was rising we saw that the whole camp had had the same type of visitors that night.

I looked up at those high walls around me. Was this going to be our life and for how long? Luckily for me and everyone else, we didn’t know yet how long we had to stay in this place. It was the 15th of February 1944, for the Japanese the year 2604.

Three days later, the 18th of February, we heard a lot of noise and people talking outside the walls and then when the gate was opened, we saw 950 more women and children walking into our prison. They came from Kediri and Madiun, in East Java. One of them was our aunt Miep. She told my mother that my uncle Pierre had been taken to the Kempeitai prison in Batavia, now called Jakarta.

This meant that both brothers were now imprisoned by the Kempeitai. I felt very sad that day.

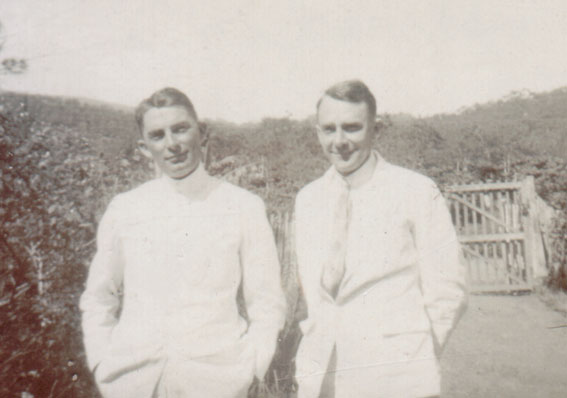

Two brothers Pierre and Theo in better times

My first Banyu Biru camp job

All of us age fifteen and up had to work. I was almost 17 years old so I had to join the group of grass cutters in our camp. It was not a heavy but a very tiring job. A Japanese soldier, Mr. Ito, stood there with a whip in his hand watching us. We were not allowed to talk or to sit on the ground. We could only squat on our haunches, and that was painful after a few hours. In the beginning we had to work three hours only, but after a while it became four to five hours a day.

The boys of our age had to do the hard work in the kitchen, and they received some extra food. The boys also had to empty the poop-barrels, an extremely dirty job. The boys had to empty the sewers coming from the toilets into those poop-barrels and take them outside the camp. Later on, when the boys had to leave our camp, the work was taken over by the young women and girls. In the afternoon our “lunch” and then our last daily meal of “starch soup” was brought to us by the boys and dished up by one of the kitchen ladies.

Our home was now only a bed, planks on the floor and the dirty mattresses on top of them and then those bed bugs. We often tried to clean the mattresses and air them for a short while outside. Every morning we killed some bugs. Many of us had mosquito nets but that didn’t protect us against the malaria mosquitoes. Banyu Biru was a real malaria region, we later learned.

Because we were living so close together, people began to quarrel, mostly about the children.

On the 10th of June that same year, 400 women and children were transported to Banyu Biru camp 11, which was a military complex. The camp was behind our camp 10, not too far away. Of course they were happy to leave this prison with those high walls and it gave us, who had to stay behind, a little more room.

My mother asked if she could get a cell for the four of us. Thank goodness we were able to leave ward 14 and move to a cell in group “C– D”. That gave us more privacy at least, though we had very little room to move around. We put two mattresses on the three cabin trunks, for my mother and Jansje, and two on the floor for Henny and me.

A normal life seamed so far away, this prison life so unreal. I very often asked myself if I would ever see Sumber Sewu again, if I could ever walk again through the jungle with my father. I often dreamed that I was with my father, but when I woke up in the morning he was gone.

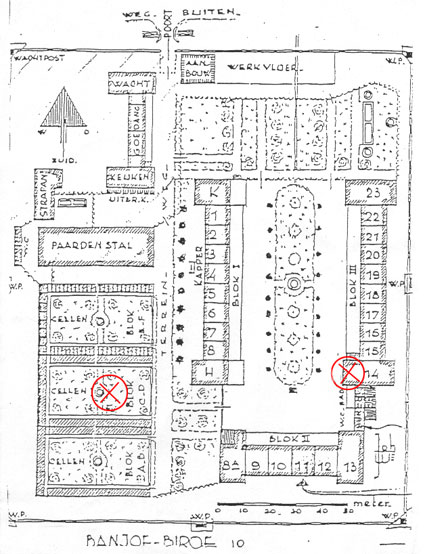

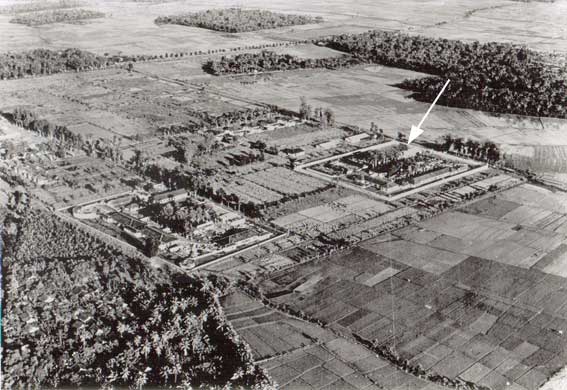

Banjoe Biroe 10

The Banyu Biru camp menu

Every morning we had roll call just after we had received our tea. We were allowed to eat our starch, our breakfast, before starting our various daily jobs. At the prison Banyu Biru, camp10, the menu was always the same from the 15th of February 1944 right until the end of November 1945.

MENU

Tea early in the morning before roll call

Breakfast: a bowl of starch

Lunch: a cup of boiled rice, a heaped tablespoon of boiled green cabbage and a heaped teaspoon of sambal, a sort of Spanish pepper

Tea in the afternoon

Dinner: starch soup with a few leaves of cabbage. One could count the small pieces

As my mother rightly said, it was just enough not to die too soon.

But in the meantime we discovered another problem and that was the malaria mosquito. Many of us fell ill, my mother, Jansje and I among them. We found out a little later why Henny didn’t get malaria, when we saw that she had jaundice.

There were no medicines and no fruit to help us get a bit better either. There were three doctors, Dr. De Kock a surgeon from Surabaya, his pediatrician wife, and then there was Dr. Kruine.

All three of them stood with empty hands. There was extremely little they could do to keep everyone alive. Dr.de Kock operated on one little boy with a razor blade and boiled water, and the operation succeeded. It was a real miracle.

Banjoe Biroe 10

The toil and moil group

On the 18th of September, 1944, a group of boys between twelve and seventeen years old, several nuns and several old men, altogether 217 people, were transported to Camp 8 in Ambarawa, not far from Banyu Biru. That very same day 200 women and children from camp Ambarawa 8 were transported to our prison Banyu Biru 10.

Many girls of my age had to take over the jobs the boys of 16 and 17 used to do, and so I came to be in a toil and moil group. We had to work outside the camp ploughing the fields, or walk to Ambarawa with several old Dutch cavalry carts loaded with all sorts of luggage, or we had to carry stones from one place to another, just to be kept busy.

It was often very hard work but I was also happy that I could walk outside of that prison every morning after roll call and after eating that sickening small bowl of starch. At least we had fresh air, a beautiful panorama and we could see the real world again with all its wonderful colours.

The Japanese camp commandants

Our first camp commandant was Sakai. In November 1944 Suzuki became our second commandant and, in February 1945, Yamada became our third and last camp commander. They not only had the Banyu Biru prison under their commands but also camps 6, 7 and 9 in Ambarawa as well as camp 11 in Banyu Biru. The camp commandants came now and then to give some orders and to tell us what we had to do as well as what was not allowed.

Our first camp keeper was Ochiai; the second one from May 1944 was the very strict Ito; the third one from December 1944 was Hashimoto, who stayed with us just for the month December 1944. Then Ishikawa stayed one month, January 1945, and in February Hashimoto came back again and stayed until May. Our last camp keeper was Wakita, who left us in August 1945.

We were told that from January 1944, we were no longer Internees. From that date on we were considered Prisoners of War, even the youngest children. And so, from January 1944 we were treated as POWs.

It was a strange situation, because in Malang we had been told that the Japanese military had put us in camps to protect us against the Indonesians. Now in Banyu Biru we learnt a different story.

My malaria attacks came more often, more or less every two weeks. With each bout I had a very high temperature, which made my “job” much harder.

My mother and my sister Henny grew very thin, and my youngest sister Jansje hardly played at all. She had quite a few malaria attacks as well. My poor mother also began to lose some of her teeth, and I felt sad to see my family slowly become sicker and sicker.

In the meantime more women and children entered our prison. On the 19th of November 1944, 600 came from Kareës and on the 21stt of November, 350 women and children came from the Tjihapit camp. The trouble was of course that when more people came to our prison, there was less food, less space, less water.

Everyone walking into our prison said the same thing: “What a horrible camp.”

Elizabeth advises that only long after the war she learnt that Koreans using adopted Japanese names were also deployed as camp guards, especially as it was no great honor for the Japanese military to perform this role. Even so, the camp commanders were Japanese and all camps in her region were under the control of the Ambarawa-based Kempeitei.

Christmas 1944

There were many rumours in Banyu Biru camp 10. The Japanese were losing the war. The Americans, British and Australians were winning.

The Japanese camp keeper and his soldiers were quick to be angered about next to nothing. The yelling became louder, and more Dutch women were slapped in the face. That must be, we thought, a positive sign since it was very clear that our Japanese suffered from loss of morale. But of course we were not sure, as we had no contact with the Indonesians either, and the Heiho [Indonesian draft laborer-conscripts] were under strict control of the Japanese camp commandant and his soldiers.

Heiho conscripts

Christmas came, a hungry, filthy, sad Christmas in 1944.

How can you dream while you are locked up in a dirty, overcrowded prison, when you are lying on a filthy mattress full of bugs? How can you dream while your stomach cries for food? How can you dream without music?

I was seventeen years old, but I became a little scared to dream at all.

Banyu Biru 10. This picture was taken after World War Two.

Banyu Biru 10 , our home, the cells were meant for 1 person only, but all 4 of us stayed there.

Banyu Biru 10 , our cells. I received the photos from Mrs.Wood.

Donata desu ka?

Everyone above 15 years old was placed on the list for night watch duty. I was on duty every fortnight between two and four o’clock at night. It was a horrible time right in the middle of the night.

There were always two of us walking together during the night, and each pair of watchers had their own territory. We were supposed to stop smuggling near the wall, but we usually did the opposite. We warned smugglers when Japanese soldiers were coming.

When a Japanese soldier would pass at night he would ask us; “Donata desu ka? [Who’s there?]” We had to learn these Japanese words but I still have no idea what they really mean.

But most of the time there was no Japanese control at all. We only saw many women and children running for the toilets at night since so many of us had diarrhea. It was quite cold at night, especially in our worn-out clothes. There was nothing to warm us up either, no tea or coffee.

For me there was always a ray of hope when walking to Ambarawa with my working group. Of course it was a long walk barefoot right over the hot asphalt road, but still when we arrived at the station in Ambarawa we came into another world.

Today the Ambarawa station is a museum.

Elizabeth clarifies that, in contrast to the men’s camps where some kind of pro-Japan indoctrination was the norm, there was no systematic education program at all in the women’s camps. In fact it was strictly forbidden to teach the children. Even though orders were barked or shouted in Japanese, neither were the women allowed to learn Japanese. “No education at all, just hard work.” Every morning, however, the prisoners bowed deeply toward the emperor in Japan.

Ambarawa station. This picture was taken by my youngest sister.

Sixty-five little Boys

On the 16th of January, 1945, 65 little boys had to leave their mothers. The boys were 10 and some of them even 9 years old. They were taken to Camp 7, a camp for boys and old men. Their fathers were somewhere in Burma, Japan or elsewhere and, from that day on, they were also without their mothers. This was a real nightmare for their mothers. The Japanese turned more and more nasty. It was clear that Japan was losing the war.

A nightmare

When we came back from our work outside the prison, we saw some cars standing outside the prison, so we understood that we had important Japanese visitors. When we walked through the gate of our prison, we couldn’t believe our eyes. Teenage-girls and young women stood in a queue, while Japanese officers were looking them over from top to toe.

We were ordered to stand in the line as well. I could feel a malaria attack coming up, so I started to tremble a little. I can’t remember how long we stood there, I was afraid that I would faint and had only one thought; “Let me please lie down on my mattress.” When the Japanese officers passed, I didn’t dare look up. I kept my head down in despair.

The very young women who were taken away by the Japanese were crying. This was a real nightmare, after all we had been through so far. This was just too horrible for words. When we could go “home” at last, I found my mother very upset, but she was more than happy when she saw me coming back. She had been so scared that the Japanese would take me away. She had wanted to tell them that they could take her instead of me. But luckily some of the others had held her back, saying that she would only make things worse. And at last I could lie down. I had a high fever by then, but I was so tired that I fell asleep right away. Later on I heard that several of the young women who had been taken away had to leave their children behind. The children were looked after by other mothers. This was a real nightmare!

Not long after this drama, rumors went around our Prison: “All the girls from ten years old would stay in Banyu Biru and Ambarawa and the mothers with the younger children would be sent to Borneo.” Luckily, this didn’t happen.

On the 3rd of May 1945, 600 women and children from Ambarawa camp 9 arrived on foot, and on the 31st of May, 350 women and children came in from Solo. The next day, the 1st of June, 150 more women and children arrived from Solo. On the 4th of June, 21 women and children came in from Ambarawa camp 6 and, on the 3rd of July, 47 came in from West Java. Then, on the 3rd of August, 50 women left the prison and were transported to Ambarawa camp 9 and on the 8th of August, 2,094 women and children walked into our prison. (Data from Japanse burgerkampen in Nederlands-Indië).

It became extremely crowded. We numbered some 5,300 women and children trying to stay alive in this rank, filthy prison. It was really disgusting. I think that it was just to torment us. I was absolutely convinced that Japan was going to lose this war against the Allied Powers. Surely this couldn’t go on forever?

My mother and Henny looked ill. They had pellagra. Big red spots broke out, especially on their arms and legs, because of a vitamin deficiency. Jansje was completely apathetic, the poor girl just sat there in front of our cell, waiting until some food was brought to us. And I had beri-beri, also a vitamin deficiency disease. My face and belly were swollen, full of water, or at least that was how it felt. My mother was losing some of her teeth, which gave her lots of trouble, and there was nothing we could do to stop this.

My poor sister Henny looked dangerously yellow from jaundice, and my poor mother was a bundle of nerves. I was quite worried about her. My mother just had to be better by the end of the war when my father would try to find us. We really had to fight to stay alive, day after day.

Elizabeth informs that all the young women and girls taken from the camps were sent to Semarang, a large port city on the north central coast of Java, from where they were dispatched to brothels for up to two months at a time. From her understanding, around 200 Dutch women and girls were forced to work as “comfort women,” alongside of course numerous Eurasians, Chinese and local women. One of the former Dutch “comfort women is an active member of the Foundation for Japanese Honorary Debt, as explained below.

The Japanese Surrender

Something strange was going on. We received a little more food than usual, and maybe it was just a tiny bit better in quality as well. It was very silent in the Japanese corner. We could see them moving, but for several days they didn’t come anywhere near us.

At last we were told that the war was over. Japan had surrendered to the Allies on the 15th of August, nine days earlier. Nine long days the Japanese had kept this wonderful news to themselves. They knew that they had lost the war and that they should have given their Dutch prisoners their freedom, but they didn’t.

We were free at last and yet we still couldn’t believe it.

In the meantime, several local women came into our prison, looking for work. Our neighbours advised my mother not to take one of the women to help her, because she wore a merdeka badge, which meant that she opposed Dutch rule. Merdeka means independence. Luckily my mother didn’t listen, and she trusted this lovely Javanese lady who brought us all sorts of food from her home, because she felt so sorry for the four of us.

One day she asked my mother if she could take Henny, Jansje and me to her home in the nearby kampung. And so the three of us went with our very nice Javanese hostess who really spoiled us. Her whole family was so nice to us as well. We had a wonderful afternoon.

I can’t remember the name of our Indonesian angel, but I shall never forget her kindness!

Fort Willem I My youngest sister took this picture in 2003

Again we are prisoners

Not long after, we were ordered to stay inside the prison because groups of pemuda, or youth defending the newly proclaimed Indonesian Republic, were trying to kill Dutch prisoners, or so we were told. With Sukarno now the proclaimed President of the Republic, his supporters among the pemuda and others refused to accept Dutch rule. Again the gate of our prison was closed. We now had Japanese soldiers protecting us against angry young nationalists. The lovely Javanese lady who had been so kind towards my mother, sisters and me was no longer allowed to enter our prison; we missed her.

Pro-Independence Rally, August 1945

I also began to worry how my father could find us now that the prison was locked again. But then I saw several Dutch men walk through the gate and so I understood that the Dutch could freely travel around Java to make contact with their families, although this was very risky. I also saw some women leaving the prison, saying that they were going “home,” and that sounded really good. After the war we learnt that thousands of ex-prisoners were killed by the pemuda, not regular soldiers from the newly formed Indonesian army (TNI).

One morning Henny and I saw one of the Japanese soldiers who was protecting us against the pemuda crying his heart out. Someone asked the Japanese why he was crying. They told us that a terrible bomb had killed his whole family. We felt very sorry for him, but we didn’t know anything about the big bomb they were talking about. Only much later did we learn about the atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Another day my mother and I were carrying our washtub to fetch water from our prison well, when some pemuda hiding in the tress outside the wall started shooting at us.

About two weeks later the Japanese soldiers left and Gurkha soldiers, serving in the British army, came to protect us.

Yes, life was definitely better than before. The only trouble was that we were still living behind walls even though the war was over.

I started helping to clean up the gudang (store) where the Japanese had dumped all sort of things. We found out that there were many boxes full with anti-malaria tablets, quinine, and several other medicines that could have saved the lives of the many who died in this prison. We were really shocked, even more so when we found a few cards that had been written to some of the women staying in our prison. In fact, they had never received their cards during the war. This was disgusting and very sad.

Our father didn’t come yet, and we had no news from him. But of course he was in a Kempeitai prison in Malang, which could make it more complicated to come over to Banyu Biru. He also had to travel alone. The other men came from camps in our neighborhood and they usually came walking in a group. Maybe my father was trying to organize something to get my mother, my two younger sisters and me to Malang.

Maybe my mother would soon receive a letter from him.

Banyu Biru, picture was taken after the war

We become refugees

It became far too dangerous in the prison at Banyu Biru. The internees from Ambarawa and the two other camps in Banyu Biru were evacuated before us. Perhaps because our prison had high walls, we were the last to be rescued.

In October 1945 the British Gurkhas started evacuating the first women and children from our prison, and of course they were more than relieved to be able to leave this prison behind them.

It was only at the end of November 1945, that the four of us finally left with the last group of women and children the horrible, dirty, foul-smelling prison. And so this last small group walked through the gate into a world of freedom, of fresh air.

But once again there was no news about my father.

Halmaheira, picture taken by my youngest sister

Final acknowledgment of the death of my beloved father

Towards the end of January 1945 in Kandy in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), where we recuperated en route to Holland, my mother received a letter from my aunt in Holland conveying the sad sad news that she found my father’s name on the death list from the Dutch East Indies. Around the 15th of May we sailed from Colombo bound for the Netherlands, a country I hardly knew. Upon return to the Netherlands, as I discovered, not all were disposed to welcome home such returnees as ourselves from the Dutch East Indies. It was only in February 1947 that my mother received official notice of my beloved father’s death.

Elizabeth and the “Foundation for Japanese Honorary Debt”

Elizabeth has not remained inactive. Quite the contrary. In later life, as mentioned, she re-visited the site of her childhood in Java as well as painfully but unsuccessfully seeking out information on the whereabouts of her father’s gravesite. Having struck up correspondence with Japanese pen-friends, she also visited Japan for a first time pondering upon Japan’s postwar society and the kind of sufferings that ordinary Japanese also endured. Even so, as confided, she still remains perplexed as to Japan’s postwar remembering or understanding of the full consequences of the wartime occupation of the Dutch East Indies.

Among other activities, Elizabeth is an active member of the Holland-based organization called the “Foundation for Japanese Honorary Debts.” As she told Japan Focus in an interview, rain, hail or snow, she and fellow members regularly picket the Japanese Embassy in The Hague. Among other questions, we asked her about the goals of the Foundation.

G.G. Please tell us more about the “Foundation for Japanese Honorary Debt,” for example, its goals, achievements, as well as problems.

Elizabeth van K. The aim of the Foundation for Japanese Honorary Debts is (to demand) an admission of guilt and an expression of regret from the Japanese Government towards the Dutch war victims of the former Dutch East Indies, that was occupied by the Japanese military from March 1942 till August the 15th 1945. We are all still hoping for a goodwill compensation from Japan for the pain and distress of the Dutch war victims, men, women and children suffered during the Japanese occupation.

G.G. Are all the members direct victims? Or do you have sympathizer members? Indeed, do you have any Indonesian supporters? Have you been able to make links with organizations in Japan, if so name them?

Elizabeth van K. Yes all members of the Foundation are direct victims. I do not know how many are still alive, but I do know that many of us have died during the last five years. We do have donors who were not war victims, but they are of course not counted as victims. Yes, we do have Indonesian members of the Foundation. They are from the Moluccas. They were soldiers in the former Dutch East Indies army. No, there are no real links with Japanese organizations as far as I know. The Foundation does go to the United Nations in Geneva now and then, where they get a few minutes to tell their story.

G.G. Any ex-“comfort women” members? How has the exposure of the “comfort women” issue impacted on the Dutch public?

Elizabeth van K. Yes, we do have several Dutch ex-comfort women, as members of the Foundation. Our Dutch Minister of Foreign Affairs, Mr. M. Verhagen has given a good speech. While he was in Japan [he raised the question] about those poor women and asked for an apology and compensation for these ladies. The Dutch people are in general not really interested in what happened during WWII in the Far East where people were occupied by Japan. The Netherlands was occupied by Germany for five long years. The WWII enemy was Germany in the Dutch eyes, not Japan.

G.G. What are the standard answers offered by the Japanese Ambassador or other officials when you speak with them?

Elizabeth van K. Only two members, the Foundation’s chairman, Mr. J. F. van Wagtendonk and the secretary of the committee, go inside the Japanese Embassy, while all others stand outside the gate for at least one hour. The Ambassador does nothing except point to the San Francisco Treaty! The Japanese Embassy is not happy at all with us standing there with our notice boards, because it attracts quite a few passers-by who ask us what is going on.

G.G. Any other comment you wish to make?

Elizabeth van K. You see we also want Dutch apologies and a small compensation from the Dutch government, so the Foundation is still fighting on two fronts. We know that Australia, Great Britain, Canada and Norway paid their war victims from the Far East, but not Holland. Quite sad really, since Holland declared war on Japan while she completely let down all the residents (Indonesians, Chinese and Dutch) from the Dutch colony.

The Foundation for Japanese Honorary Debt has edited a small book in Dutch and English with 60 stories by or about the experiences of Dutch people in Japanese-occupied Dutch East Indies. The stories include those from men and women in Java and Sumatra but also accounts from the Burma railroad. The English version of the book is titled Eyewitness to War.

Posted at The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus on January 1, 2009.

Recommended Citation: Elizabeth van Kampen, “Memories of the Dutch East Indies: From Plantation Society to Prisoner of Japan” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 1-4-09, January 1, 2009.