War, Memory, the Artist and The Politics of Language

Artists Hong-An Truong and elin o’Hara slavick

This conversation between two artists draws on, presents, and discusses visual representations including video, drawings and maps pertaining to the Nanjing Massacre and the US history of bombing. Discussion offers reflection on war, memory, history, biography, the relationship between language and visual representation, protest, the possibility of reconciliation, and the role of the artist in response to war.

Slavick – We are both artists who utilize history, memory and the archive to explore specific historical events. While we both focus on Japan here, we have chosen different aspects of history and utilize different methodologies and visual strategies in dealing with the subject. Initially, I was invited to contribute the drawings of Asia, including those of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, from my series Protesting Cartography for the Hiroshima Anniversary issue. Having been inspired by your work over the years, I invited you to discuss our related yet very different projects in terms of ethics, politics, history, memory and language.

Truong – When you first asked me to participate in this conversation with you, I was excited but a bit hesitant. First off, I was worried because my project has an uneasy relationship to “history.” Rather than being about history, or trying to re-tell history, or suggesting an alternative to history-telling, it is more interested in calling into question how we produce history by engaging the individual players within a bigger history. While your project provides a lot of information to the viewer, important information that most viewers might not know about (where and how much the U.S. has bombed around the globe), my work isn’t necessarily trying to give a history lesson.

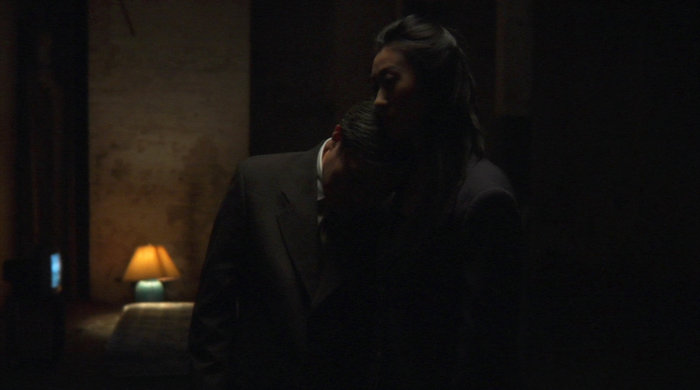

A Measure of Remorse is a single channel video installation that is part of a larger project provoked by the life of writer Iris Chang, author of The Rape of Nanking (1998), which brought intense and overdue attention in the English-speaking world to Japanese military atrocities committed against the Chinese in WWII. Exploring historical violence and the nature of apology through language, the body, desire, and trauma, the video re-imagines a confrontation on PBS in 1998 between Chang, the Japanese ambassador to the U.S., Kunihiko Saito, and journalist Elizabeth Farnsworth. The video is not a re-enactment of the past, but rather a kind of future made dark and deeply sensual, almost as an effect of Chang’s suicide in 2004. It raises questions about the effect of performative utterances – like apologies – when it comes to historical violence. The three figures acknowledge hurt, even death, and ask us about the claims our memories and voices can make against the past.

So in some ways, the project makes abstract the specifics of the history as a way to crystallize broader questions about trauma, memory, and language.

A Measure of Remorse may be viewed in full here (requires Quicktime 7). [The images here are stills from the video.]

Slavick – Who are the 3 protagonists in your video A Measure of Remorse? Are they countries?

Truong – In one sense they are, but on a basic level, they are three people. Part of what was compelling to me about this interview (you can read the full transcript here) was the way in which the two individuals interviewed oscillated between speaking for themselves and speaking for their countries / their people. Their positions are not simple, of course, and even an attempt to speak for a group of people is problematic. In the case of Iris Chang, she is a second generation Chinese American who is advocating for the Chinese victims (and their families) of these atrocities. I am interested in the way that political violence operates on the individual and on the nation, and in the slippery spaces in between these sites of trauma. Thinking about larger questions of nation-hood, nationalism, and the State, people have very strong feelings about whether and how governments should do the work of reparation. What is the role of memory in dealing with the history of political violence? My project does not re-hash national positions on this particular issue, but asks, how war and violence affect us as individuals transnationally.

Slavick – It is interesting that these people are individuals; yet in the video they do not speak – neither for themselves nor for their countries. The soundtrack is from PBS, a mass-media source. Do you see any contradiction there? It is as if they are slow-moving, embracing and beautiful pawns. Are we pawns in history, in the present?

Truong – Absolutely not –we are not pawns in history or in the present. The silence of the characters goes back to the question of language. How do we make ourselves heard? How effective is language in dealing with sorrow and pain and regret? How can we perform differently with our bodies than with our words? I follow Judith Butler’s thinking through performativity, both in words and with our bodies. In the PBS interview, the language that is used is a regulated discourse – the language of political debate, where one speaks for the institution that he or she represents. This is what Iris Chang is getting at in her frustration about the lack of an apology. Can the Ambassador speak for himself and not the nation? No. He speaks for the nation because he is constrained by the norms of political speech—and he does so because of his specific job, not just the general framework of political speech, which regulates the other two participants. We are also disciplined in our bodies. The three characters would never have an opportunity to engage each other’s bodies in the way that they do in the film. I bring these actions of tenderness, of embrace, of a stillness and slowness with the three characters – in and against language – as a way to challenge our performativity, and how we are disciplined in both language and body, as it relates to questions of history, violence, and remorse.

Slavick – Do you think that a government or history has a heart?

Truong – I don’t think so, but I do think that they know time. They know how to use time. There are differences in the way that we experience, measure and think about time. Time is an abstract notion that becomes concretized through art, science, and social structures, but also through history – history as it is relates to what we know, how we write and talk about it, what knowledge gets proliferated. So no, government does not have a heart; history does not have a heart, but they are bound up with time, bound up with consciousness.

Slavick – But memories, unlike history, come all mixed up together time-wise. They are rarely chronological. I don’t quite know how to separate consciousness from emotion (the heart) and am fearful of a government that does not act with compassion (again, from the heart).

Does the chatter, noise, impossibility to comprehend much of the soundtrack symbolize the impossibility of communication and of changing history? Does it symbolize the difficulty of a true apology, of understanding and accepting an apology, and the fact that an apology does not undo the action? Also the suppression / denial of information? What was your strategy in making so much of the soundtrack incomprehensible?

Truong – I wanted to create a kind of trance-like soundtrack, where the words become abstract sound and only some comprehensible sentences emerge, to draw attention to the problem of language. I had in mind J. L. Austin’s concept of language and performative speech acts — the idea that to say something is to do something — and what he calls ‘misfires’ when performative speech acts fail; they become ‘unhappy.’ In this project, I am not championing the spoken over the written word or vice versa. I was thinking about Derrida’s concepts of difference — that the spoken word is always in reference to the written word; it demands the written word so it renders what is spoken as suspect. The lack of clarity in the soundtrack is about my suspicion of spoken language and how we perform with language. It wasn’t about making clear who was in the right and who was in the wrong (in terms of the actual apology from Japan to China) but rather, about the fallibility of language and our struggle to articulate our sorrow, remorse and pain.

I think Derrida’s concept of différance is useful in conceptualizing the trauma of war violence through temporal and spatial terms. Différance is a play on words – it means both to defer and to differ, a deferral in time and space. Words are never adequate because they merely refer to more words. Words are fundamentally different than what they signify, and meaning is always deferred through language. Thus, this present, rather than assert itself as presence itself, splits that moment in a gesture of différance – a split that marks the trace of the future and the trace of the past in the present.

Slavick – Do you identify with one of the women in the video?

Truong – I identify with Iris Chang, but not without reservation or critique. Her life was the impetus for this piece and I hope to make a longer work about her soon.

Slavick – Could you speak more about Iris Chang here? I am particularly interested in your identification with her. How do you identify yourself? (I identify myself as a reluctant but privileged American citizen with roots planted firmly in Germany and France – for better or worse – wanting to be a citizen of the world.)

Truong – Iris Chang was born in the U.S., second generation like me. Her parents were Chinese academics, and she grew up in the suburbs. Her story is very different from mine (my family were refugees who fled Viet Nam after the end of the U.S. War; I was born soon after they arrived in the U.S. and I grew up in various parts of the country, refugee-poor). But there is a similarity in how we approach our family histories and shape our identities. She grew up hearing stories of the atrocities and genocide at Nanking, and these memories, while not from her own experience, functioned as her own. This parallels my own engagement with the U.S. War in Viet Nam, which has compelled me to make the work that I do. It’s what Marianne Hirsch has called post memory to describe the relationship between people of the second generation to the traumatic experiences that occurred before they were born, and the ways that these memories get transferred. Post memory is an in-between space where memory (which includes second-hand memory, memory through stories or archives, memories through the media) splits one’s sense of self, between here and there, between now and before.

Slavick – We are all second generation to traumatic experiences that occurred before we were born, processing the ways these memories get transferred: physically through lingering contagions and landmines; emotionally through countless absences, lacks, losses, denials, truths and lies. Of course, being second generation to the perpetrators or to the victims are very different positions, but ultimately, we all suffer the consequences of history.

Pierre Peju writes in Clara’s Tale, “War was everywhere. It had gone on for so long that people had forgotten what caused it…. In Germany, memories of the disaster that occurred still hang heavily, but nobody speaks about them. Their shadows lurk in the artificial post-war serenity, among the still visible traces of violence and ruin. A veil of unspoken words shades people’s kindly actions and disturbs the apparent innocence of things…Will my own life run its entire course in a similar kind of peace? A heavy, dense peace. An amnesic peace.”

Truong – For Chang, the stories she heard growing up were the impetus for her research into the history of atrocity and ultimately the writing of The Rape of Nanking (1998), and she committed her short life to seeking justice and reparations for its survivors. While her book was a best-seller, and she was highly praised for it in the Chinese-American community and beyond, she also received a lot of criticism for that book, in the U.S. and, especially, of course, in Japan, where the book still causes a lot of controversy. She also received death threats and personal attacks, leading to periods of mental instability. In 2004 she was researching her fourth book, on the Bataan Death March (an atrocity which also occurred during WWII, when the Japanese military moved American POWs many miles without rest or adequate food) when she was hospitalized for mental health reasons. She committed suicide soon after that. I am interested in how she struggled with this history that she could not claim as her own experience but which drove her commitment to political and social justice. But her life’s research and writing about war and violence also fueled her psychological instability. I am interested too, in how her own identity as a strong, outspoken, Asian American woman affected the way that her work was read and the criticism she received. In terms of her writing style, she had an ardent belief in the first person narrative and used emotional language in what is ostensibly considered history writing.

One of the reasons I chose to approach this topic the way I did is that I did not want to make a film about Iris Chang; I did not want to pathologize her, nor did I want to glorify her life and her work. On the contrary, I am using her story and this history critically as an attempt to get at wider questions about the role of memory in our understanding and relationship to war violence. Political violence is happening every day and quickly becomes the past. I was interested in this history in particular because of the ways that it can remind us how past political violence is also very much now.

I think the relevance of this story is made clear in the persistence of fraught relations between Japan and China, and the ways that this history – this historical memory – rears its ugly head in unexpected moments. There are Chinese activists who stage protests every time Japanese revise their school textbooks because of the way that this history is treated. Simply, the Chinese believe that the history is not being told truthfully – and this of course, has huge implications in the way that the Japanese see themselves and understand their history in relation to China and the rest of the world.

For me, though, my project does not take a humanist approach to violence. I am critical of a humanism that is founded upon a perceived universal moral order. To have empathy can be powerful – but it cannot work towards justice all by itself because I think it also problematically relies on the idea that there is an essential “goodness” of the individual and also doesn’t account for relations of power. I think this is what is weak about liberal democracy. It assumes that you have power without having to seize power. Humans don’t have an ahistorical essence – it’s important to remember that we are desiring subjects, operating within a set of power relations. We have to be critical of this and self-reflexive so that we can be active in our resistance.

In the video I wanted to create a tension between the words and the bodies of the three characters. The language that the characters used in the conversation fit within established codes that are based on a perceived moral order. The contrast between the language and the bodies was about proposing a kind of individualizing ideal, an experience of ethics that might question what and who we are. I think the framework for political action is not based on empathy within a set of moral rules, nor is it based on some notion of an essential sameness (our humanism), but rather a reflexive notion of the self where one can be something other, where difference and alterity are taken up.

Slavick – How do you see the difference in reception of a video vs. a series of drawings? We are both dealing with specific violent histories but utilize different media. I know my choice of drawing was deliberate, even though I am trained as a photographer. And I am sure video was a deliberate choice for you. Could you talk about why and how you make those formal decisions?

Truong – Since I started making videos, I have been dying to make a purely photographic project, and it just hasn’t happened. I just think in moving images, I am thinking in time-based images. I think electronically! In both sound and image — I am always thinking of movement. Part of it is because I am drawn to the archive, the digital archive, the photographic and filmic archive, and so I am just working in the medium in which I find my source material. In this case, it was the PBS broadcast of this argument between Iris Chang and the Japanese ambassador. I love video because of the way that it can be so evocative. It is a language that so many are familiar with.

Slavick – You make me want to make videos and films.

Truong – And you make me want to work on paper!

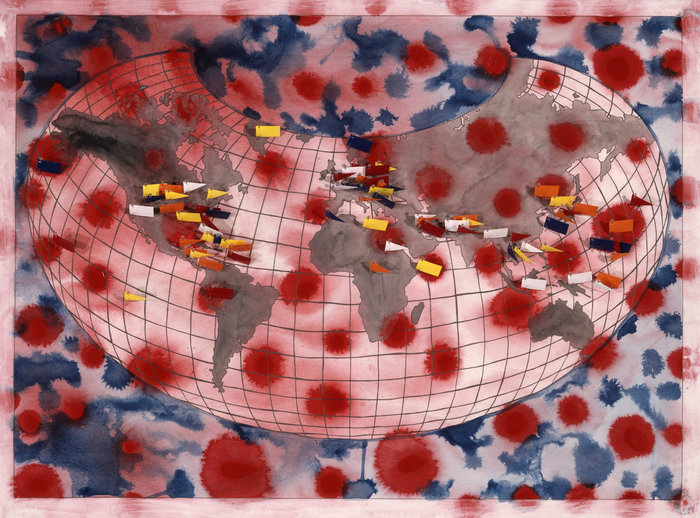

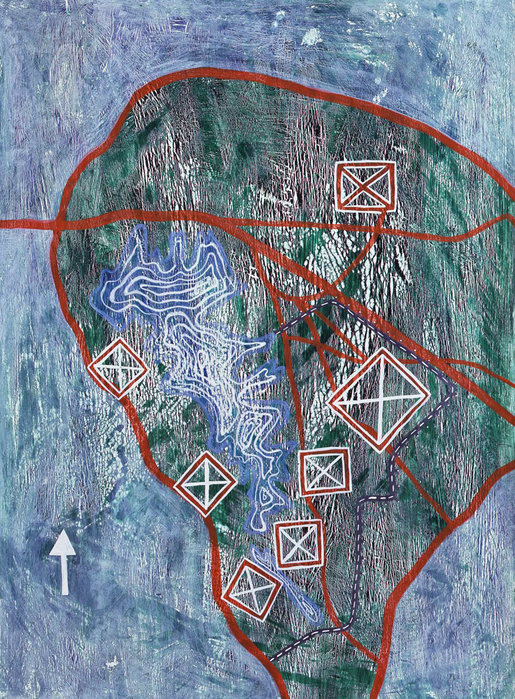

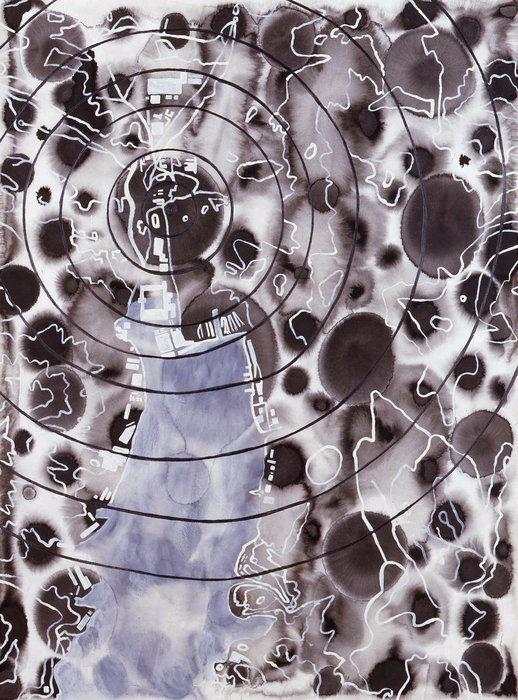

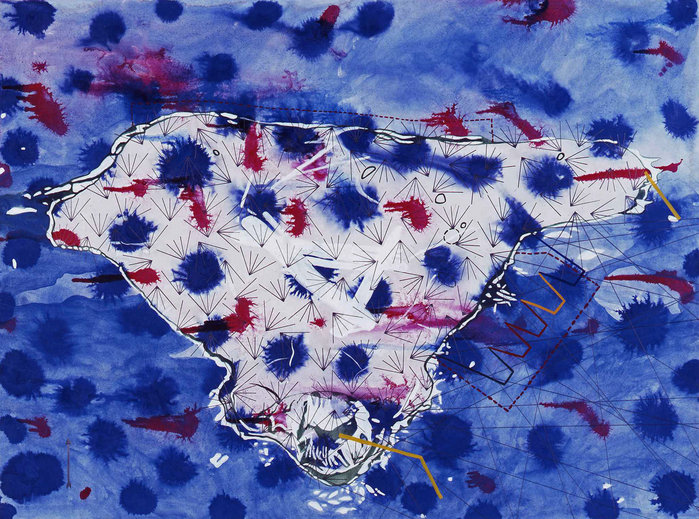

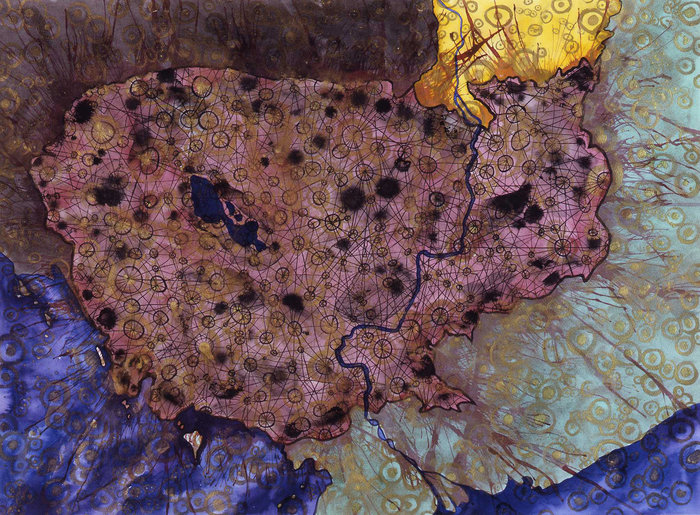

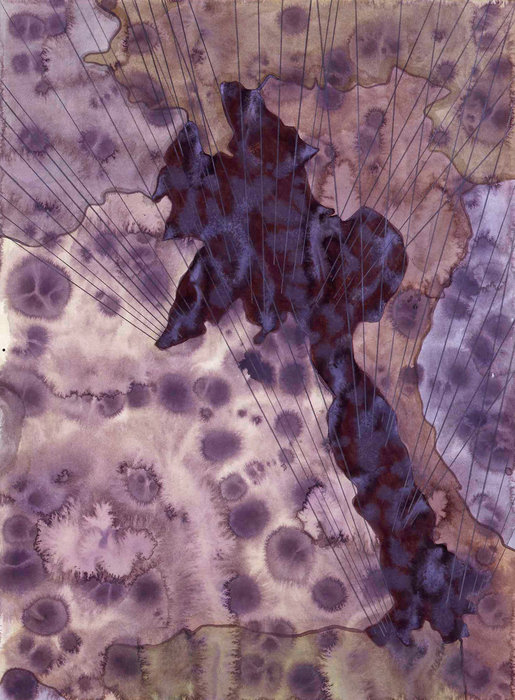

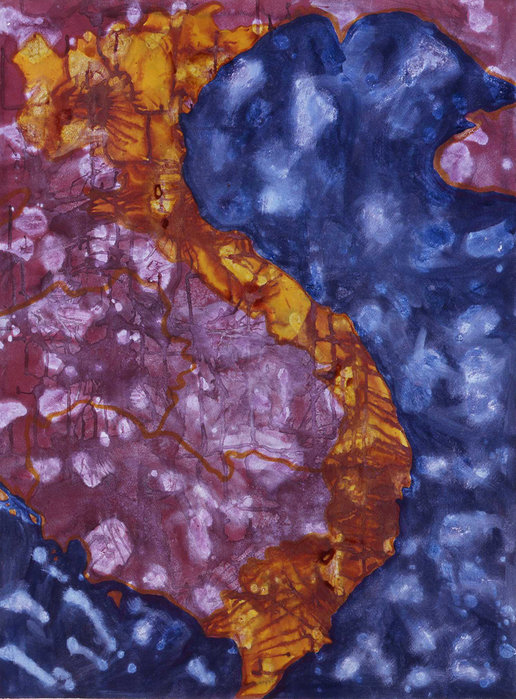

The images that follow are from Protesting Cartography: Places the United States has Bombed. All drawings are mixed media on Arches papers, 30 x 22 inches, unframed.

World Map, Protesting Cartography: Places the United States has Bombed

1854 – Ongoing

Flag pins mark bombsites for which there are corresponding drawings.

|

Dugway Proving Ground, Utah, USA 1942 – Ongoing |

Dugway is a “massive firing range that for 50 years was the U.S. Army testing ground for some of the most lethal chemical, biological and nuclear weapons ever made. A slope of mountains to the east is pockmarked with hundreds of fortified bunkers storing enough toxins to eradicate mankind. Ground water is fouled with carcinogens. This was where the cold war was waged, not in battlefields in foreign lands, but in factories, laboratories and testing ranges.” – Tony Freemantle, Houston Chronicle

|

Nevada Test Site II, USA 1955 – 1968 |

The drawing takes as its reference a photograph from Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory of a Project Schooner (part of Project Plowshare) crater and a football field (for scale), which was made by a 35-kiloton nuclear bomb.

“From 1957 to 1973, scientists and engineers working under the direction of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission and its Livermore laboratory investigated, experimented with, and promoted the idea of “peaceful” uses of nuclear explosives through a program called Project Plowshare. Proponents confidently argue that the “geographical engineering” of harbors, canals, dams, and mountain passes could be accomplished safely, economically, and scientifically by means of nuclear-blasted excavation. But the nuclear earthmoving explosions produced large amounts of radioactive fallout, and with it, significant challenges to the program on scientific grounds. The Project Schooner cratering explosion produced the highest levels of fallout in Utah recorded since 1962, and sent radioactive debris across the Canadian border.” – Scott Kirsch, Peaceful Nuclear Explosions and the Geography of Scientific Authority

Slavick – Protesting Cartography – Places the U.S. has Bombed (1998 – 2005) is a series of 60 drawings of places the U.S. has bombed. They include Dresden, the Bikini Atoll, Guatemala, Nicaragua, the Congo and France, among many other places. Pictured in this essay are the World Map, several of Asia, and two domestic ones of atomic test sites. (Order the book: Bomb After Bomb: A Violent Cartography) The drawings are manifestations of self-education on the subjects of U.S. military interventions, geography, politics, history, cartography, and the language of war. The drawings are also a means to educate others. The drawings are “beautiful” so that the viewer will take a closer look, slow down, and contemplate the accompanying information that may implicate her. As a photographer aware of the military’s use of the aerial view that flight and photography provide, using the aerial view seems like a logical choice to me. I utilize surveillance imagery, military sources and battle plans, photography and maps, much of which is from an aerial perspective. Maps are preeminently a language of power, not protest, yet I offer these maps as protests against each and every bombing.

Truong – I want to think about the relation between image and text — how do they work together and / or against each other? For your work, the accompanying titles are important for a kind of pivot in the reading and reception of the work. I wonder about the language that you use and how it works. Can you talk a little about your choice of language?

Slavick – It is important that people see and experience the drawings first as drawings, that is, as visual things, because I think the subsequent and accompanying texts, (usually hung beside each drawing as a title and published in my book at the end as “List of Annotated Plates”), if they choose to read them, shock them out of their initial enjoyment of the drawings as cartographic, abstract and semi-modernist compositions and into a more politicized, active and historical field. Mostly, the titles come from other sources – historians, writers and activists like Howard Zinn, Sven Lindqvist, James Bradley, William Blum, Terry Tempest Williams and Jeffrey St. Clair, and media sources like the New York Times and the Washington Post. I probably spent as much time finding these texts as I did on the drawings. During my research, I discovered previously unknown places the U.S. had bombed, including its own territories (Atomic tests in Nevada, Alaska, Utah, Mississippi and New Mexico; the fire bombing of a neighborhood in Philadelphia; bomb tests in Puerto Rico and North Carolina) and realized that I was giving myself a history lesson. I felt compelled to share this information with others. Perhaps this comes more from my position as an educator than it does from me as an artist, but I am a big fan of art that is described, often disparagingly, as didactic, pedagogical, propagandistic and political.

The drawings do not show any people. As Howard Zinn writes in the foreword to my book, I do not show “bloody corpses, amputated limbs, skin shredded by napalm.” Somehow though, the drawings compel the viewer to envision those things. The text does not show any people either, but it literally describes the historical events that took place – the number of the dead, the tonnage of bombs dropped. The text also compels you to imagine, to empathize. While some of the text is from an overtly political position, most of the titles are factual. While the drawings consistently work against the authority of maps as sources for specific information produced by those in power, the texts provide lots of specific information. I hope this provides a dynamic tension between the images and the text. The drawings seem to compel viewers to “figure them out” and once they start reading, they usually do not stop.

|

Hypocenter in Hiroshima, Japan 1945 |

The atomic bomb called Little Boy “dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945 turned into powder and ash, in a few moments, the flesh and bones of 140,000 men, women, and children. Three days later, a second atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki killed perhaps 70,000 instantly. In the next five years, another 130,000 inhabitants of those two cities died of radiation poisoning. Those figures do not include countless other people who were left alive, but maimed, poisoned, disfigured, blinded.

A Japanese schoolgirl recalled years later that it was a beautiful morning. She saw a B-29 fly by, then a flash. She put her hands up and ‘my hands went right through my face.’ She saw a ‘man without feet, walking on his ankles.’” – Howard Zinn, Hiroshima: Breaking the Silence

|

Nagasaki City at Bombing Time, Japan 1945 |

On the morning of August 9, 1945, the U.S. B-29 Superfortress dropped the nuclear bomb code-named Fat Man over the city. The explosion generated heat estimated at 7000 degrees Fahrenheit and winds estimated at 624 miles per hour. About 70,000 of Nagasaki’s 240,000 residents were killed instantly and up to 60,000 were injured.

Truong – It’s interesting that the text is what anchors the work politically – it is the pivot on which the meaning of the work is understood. So the text is incredibly necessary, and I see it as completely part of the work. We are both trying to challenge the negative perception of didactic political approaches to art practice. Considerable recent work takes up the language of political protest and uses it to both critique and engage (Sharon Hayes, Emily Roysdon, or even The YES! Men). In particular, a lot of work that takes up the language of the news media is about critiquing it. But you are taking that language, and lots of other languages, to simply inform. It’s interesting that these texts must be taken as facts. Do you see these annotations as really doing the work? Would the work function the way that you would want without them, and does that mean the texts then are the authority?

Slavick – I do not believe in one meaning of the work (or of any work). There have been pro-bombing people in the audience who appreciate this project too and that is fine with me. I strive for a multiplicity of experiences and understandings of my projects. I think the text is critical to the piece for you and me and many others, but not for everyone.

The language of political protest has always been utilized in art and has consistently gotten lots of attention – from Goya and Kathe Kollwitz to Hans Haacke and Alfredo Jaar, to name a few. I do think the text “does the work” in some sense, but not all of it. The drawings and titles, are co-dependent. I think the drawings, while working against authority and within subversive cartography, still do provide facts, information, and subsequently “authority” – this really is a representation of a real place where a bombing occurred. Ultimately, I am not sure that we need to distinguish between text and image in terms of language. Visual information functions and is understood in a very similar way as written text. Both function as language, even if they appear very differently.

I did feel a bit unqualified to make such a historical project, doubting my position and knowledge. Expertise makes us all insecure when we move outside our prescribed fields. Utilizing the texts from other sources did provide me with a sense of confidence and a community of support, even if I had to create it.

I think about A Measure of Remorse here. The “facts” are the PBS story that you use as a soundtrack, even though much of it is inaudible, we comprehend enough of it to know that this conversation really took place. The soundtrack is paired with a completely fictional reenactment or staging of the real event that happened years ago. Which form carries more authority – the soundtrack or the imagery? One reason you make me want to make videos and film is how these two elements are seamlessly contained within one piece, rather than placed side by side as autonomous elements.

We are both challenging the way history is told and represented, the way things are remembered, along with challenging traditional perceptions of art practice as a purely formal exercise. They are all inherently dependent on each other – the sidelining of conceptual, political, ethical practices for the privileging of mainstream history and sanitized memory.

|

The Firebombing of Tokyo, Japan 1945 |

On the night of March 9-10 American B-29 bombers attack Tokyo, a city of 6 million people. 600 bombers drop 1,665 tons of napalm-filled firebombs, destroying 16 square miles. “In one horrific night, the firebombing of Tokyo — then a city largely of wooden buildings — killed an estimated 100,000 people.” – Howard French, The New York Times, March 14, 2002

|

Assault on Iwo Jima, Japan 1944 – 1945 |

“B-29 Superforts and B-24 Liberators pummeled the island mercilessly. Iwo Jima was bombed for 72 consecutive days, setting the record as the most heavily bombed target and the longest sustained bombardment in the Pacific War. Every square inch of the island was bombed. The 7th Air Force dropped 5,800 tons in 2,700 sorties. In one square mile of Iwo Jima, a photograph showed 5,000 bomb craters – all this on an island 5.5. miles long and 2 miles wide.” – James Bradley, Flags of our Fathers

Truong – This also has to do with our choices of medium. We’re both deliberate about how we approach the topic — we are researching and turning to archives. I am curious about your decision to work with maps. How do you think about the relationship between the abstract (shapes / color) and the concrete (place / violence)?

Slavick – I had never worked with maps before but it was the logical form for this project for several reasons. First, as an American, it is crucial that I identify myself as a citizen of the bombing nation. Utilizing the cartographic perspective that is inherently photographic (I am a photographer) provides a bomber pilot’s view. I would never drop bombs and am opposed to each and every bombing, but it seemed critical to put myself in that position. Second, there is a long history of maps. They are usually used as instruments of power, determining borders and lines of private property, providing the source from which governments decide where to bomb. They are also considered to be true, factual representations of a place. I wanted to undermine that power. Bombs do not stay within their intended borders – chemicals and toxic agents flow freely across borders. Ideologically, bombings create more “terrorists,” (What is the difference between a terrorist and a soldier?), not just in the country under attack but in neighboring countries as well. I chose not to include geographic or cartographic symbols or information (other than the demarcation of a country or locality’s shape in many cases) as a means to open up the possibilities for reading a map, to disengage maps from the clenched fist of authority.

Some of the color choices were very deliberate, based on the source material from which I was working. For example, the Congo is the same ochre yellow color that it was in the old atlas and it is the one drawing in which I turned the orientation of the country on it’s side because the history of that country’s borders and name is so complicated and constantly changing. The World Map, that has flag pins at each place for which there is corresponding drawing, is fairly red, white and blue – patriotic colors in the name of professed democracy and freedom. But for an artist who usually has a reason for everything and a purpose for each formal decision, I was surprised by the lack of correlation between colors and specific countries and events. Sometimes, it makes sense: The Firebombing of Tokyo is full of flame red and burning yellow, ash black and the bay is bluish, the landscape green; The Nevada Test Site II is dessert sand beige, even the sky is striped white and brown, the bomb crater black and injured red. But more often, the colors do not make sense: Vienna is pink and Poland and Iwo Jima are both white with dark blotches. I tried to make each drawing different to avoid redundancy and so that people would stay interested in them.

And I also enjoyed making them – watching the ink bleed, experimenting with acrylic resist, intuitively choosing colors and patterns. This felt wrong to me because I was so troubled by the content, by the events, but again, the process kept me working on a very depressing topic and it became clear to me that to keep people going with it, I had to make them beautiful. There is a lot of red for blood, black for death, blue and bleeds for water, concentric circles for targets and the spiraling aftermath, grids and lines to represent the map, the grid of power. Each one is also different because each place has a very specific history. I did not want to collapse each place into one big target or try to equalize the traumatic violence.

|

Cambodia 1969 – 1973 |

“From 1962 through 1973 the United States struck Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia with eight million tons of bombs, more than three times the amount it dropped in World War II. U.S. Policy in Cambodia from 1969 to 1973 played a crucial, if unintended, role in building support for the Cambodian Communists (the Khmer Rouge). A once insignificant rebel group, the Khmer Rouge did not gain strength until the United States began secretly bombing Cambodia.” – Christian Appy, Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides

|

Laos 1964 – 1973 |

“Between 1965 and1973 more than 2 million tons of bombs rained down upon the people of Laos, more than the U.S. had dropped on both Germany and Japan in WWII.” – William Blum, Killing Hope: U.S. Military and CIA Interventions since World War II

“Fred Branfman was one of the first Westerners to expose the fact that the United States had been secretly bombing northern Laos since 1964. Many of the attacks focused on the Plain of Jars, a high plateau controlled by the Laotian Communists, the Pathet Lao. It had been populated by some fifty thousand Laotian peasants who lived among six-foot-tall vessels believed to be ancient funeral urns – the famous jars of the plain. Branfman writes, ‘Every single one of the refugees told the same basic story. The bombing started in May 1964, slowly accelerated, and got really bad in 1968.’ I later found out that when Johnson declared the bombing halt over North Vietnam just prior to the November 1968 election, they simply diverted all the planes into northern Laos. Then Nixon and Kissinger came in and leveled the entire Plain of Jars.

Many of the air strikes dropped ‘pineapple bombs’ – antipersonnel bombs. They couldn’t destroy trucks or antiaircraft emplacements. They were only meant to kill people. They’d shoot two hundred and fifty pellets across an area the size of a football field. Then they refined them with these little fleshettes so they’d enter your body and were almost impossible to remove.'” – Christian Appy, Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides

Truong – The way that you talk about this makes me think of them as memorials – maps that, unlike their typical function of telling you where you are, memorialize what was once there, what once existed. And because it doesn’t have the function of what we want a map to typically do, it pushes us to want to know more, to seek out information.

Slavick – Exactly. My work has been about memorials for a long time. I just came back from 6 months in Lyon, France where I was making work inspired by the French Resistance during World War II. I wrote about and photographed memorials. (My photographic essay comparing memorials in France to those in Hiroshima, Japan, is forthcoming in the Canadian journal Public.) Memorials mark history and provide a constant reminder of what once happened. Many memorials are monumental. When all 60 bomb drawings are exhibited together, they do verge on the monumental, but as autonomous drawings, they are fragile paper documents offered as witness, testimony and in memory of all those who perished beneath our bombs.

|

Korea 1950 – 1953 |

“American airpower in Korea was fearsome to behold. As was the case in Vietnam, its use was celebrated in the wholesale dropping of napalm, destruction of villages, bombing cities so as to leave no useful facilities standing, demolishing dams and dikes to cripple the irrigation system, wiping out rice crops, saturation bombing, and a scorched earth policy. It is worse than useless to destroy to liberate.” – William Blum, Killing Hope: U.S. Military and CIA Interventions since World War II

“Three years after the beginning of the war, a cease-fire was finally signed. Everything was back to where it had been in the beginning, with almost the same borders as before the war and the same unfulfilled dream of reunification. No one had won. Everyone had lost. The war is calculated to have cost the lives of 5,000,000 people, by far the majority of them civilians.” – Sven Lindqvist, The History of Bombing

Truong – Can you talk about your influences and references?

Slavick – I love Sue Coe and Kathe Kollwitz and their insistence on the hand being present in the work; the hand marking resistance, scratching alternative histories and slowing us down; making work against war. I am probably most inspired and challenged by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, how he addressed deeply personal and political issues with surprising and seemingly banal forms – heaps of candy as bodies, side-by-side clocks as gay lovers. I grew up loving the modernists and loved echoing some of their formal choices of abstraction, automatic writing, subconscious and childlike expressions, but for a different reason and in a completely different time, although war is ever present. I also grew up in an activist family where I was taught that our every gesture can change the world.

Truong – Can you talk about your deliberate choice of materials? Why drawing?

Slavick – I chose drawing because of my ongoing struggle with the problematic nature of photography. While the drawings are not photographs, they are photographic. Many of them are drawn from photographic sources and most of them are from an aerial perspective that is inherently photographic. But I can not make photographs of these damaged places. I did not survive the bombings as a victim but as a war-tax-paying citizen of the bombing nation. Even if I could make photographs, I would not because there are already too many photographs – too immediate and too brief – countries and lives reduced to singular images. I hope that if I labor on a series of drawings in which the artist’s hand is visible, that people will work to understand them on a deeper and more complicated level than they might when seeing a photograph.

|

Vietnam 1961 – 1971 |

“North Vietnam had been the target of secret U.S. military operations since 1961. In early 1965, just months after his landslide victory over Goldwater, Lyndon Johnson launched Operation Rolling Thunder, the sustained bombing of North Vietnam. In June, huge American B-52 stratofortresses began bombing targets in South Vietnam, each plane dropping up to twenty-seven tons of explosives per mission… Of the 53,193 American military fatalities in Vietnam, more than ten thousand were classified as ‘noncombat deaths’. U.S forces also suffered more than three hundred thousand wounded. In 1995 the Vietnamese government announced that 1.1 million Communist troops were killed and six hundred thousand were wounded during the American War.

The hardest figures to find reliable estimates for are the number of Vietnamese civilians killed during the war. Most estimates indicate that civilian deaths exceed combat deaths. The Vietnamese government estimates that two million Vietnamese civilians died during the American war. In total, the war extinguished some three million lives.” – Christian Appy, Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides

Truong – I am interested in how you think about mapping in the context of experimental geography and radical cartographies. Do you think of your work as a spatial practice? You talk about the specificity of history, but do you also think about what you are doing as re-production of space?

Slavick –Yes, these drawings must be considered as re-productions of space because that is what they are and I was aware of that as I made them. I wanted to re-present not only each place that the U.S. has bombed, but also the space between the airplane and the land, between the bomb and the people under the bomb. I also wanted to image the enormous space that these bombs have destroyed. We, the U.S., have practically bombed everywhere on earth, or at least a place close by.

Truong – I ask this question because cartography is having such a renaissance in the contemporary art world right now, fueled by the prevalence, proliferation and access to the way that we can map things nowadays (think Google Earth, MapQuest and the like).

Slavick – Many of the sources for my bomb drawings came from the web – interactive military battle maps, surveillance and aerial views from the Department of Defense and activist sites for example. It felt like swimming upstream to then translate these globally accessible maps into hand-drawn images, but also critical to the process, both in production and reception. I wish I thought electronically like you do. I am too worried that the plug will be pulled, my hard drive will crash, or that I will inadvertently delete a thought or emotion.

Truong – It’s a means of production that has been taken up by artists practicing a kind of critical geography whose works overlap with other disciplines like urban planning and architecture and are supported by fantastic organizations like the Center for Urban Pedagogy in New York. But I’m thinking through the way they function as maps, how they might create another space for a viewer (ostensibly an American viewer) to imagine the place of war, to imagine the U.S.’s history of violence. I think it’s important that you keep reminding us that the U.S. is also you – it’s also the viewer and it’s also me – to remind us of our complicity as Americans. But I am thinking about the role of map-making and space-making within that, and the ethical responsibility of re-presenting our orientation of the world that adequately addresses the imbalances of power and violence. The artist and geographer Trevor Paglen has written about this – the idea that experimental geography is a way of taking up a position within the politics of lived experience. The production of space is indeed a political act. Can you talk about how you see map-making as a kind of political act, and do you related it to a concept of ethics? What is your concept of ethics in this regard?

Slavick – I am familiar with the cartographic trend in the contemporary art world. Two of my bomb drawings are included in Katherine Harmon’s recent book, The Map as Art: Contemporary Artists Explore Cartography. There has been much written about it but I can’t help but think that much of it comes from our sense of placelessness. We can be anywhere and everywhere (via the screen), yet we are nowhere (always in front of our screens). Making maps gives us a sense of place, even if that place is war-torn or imaginary. I can’t imagine making anything as an artist without “taking up a position within the politics of lived experience.” Experimental geography is just one tool among many that you can use. I would argue that the production of art in itself is a political act, that the production of art is the production of space.

Ethics are intertwined with empathy. I believe in an ethic of reciprocity – do unto others, as you would have them do unto you. I believe in trying to cause no harm. I try to identify and stand in solidarity with those who suffer, especially due to my country’s policies. I am not interested in art for art’s sake. I believe we all have an ethical obligation to make our work serve a greater good. Art is no exception.

elin o’Hara slavick is an artist and Distinguished Professor of Art at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill where she teaches studio art, theory and practice. She received her MFA at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and her BA at Sarah Lawrence College. Slavick has exhibited her work in Hong Kong, Canada, Scotland, England, Cuba, and across the U.S. and Europe. Upcoming shows of Hiroshima: After Aftermath are scheduled for Chapel Hill, North Carolina, Lawrence, Massachusetts and Hiroshima, Japan. She is the author of Bomb After Bomb: A Violent Cartography, (Charta, 2007), with a foreword by Howard Zinn. Slavick’s essay “Hiroshima: A Visual Record” appeared in Asia-Pacific Journal in 2009. Her exhibit, Aftermath, on the aftermath of wars, is in progress at the Fedex Center for the Arts, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill from September 15-November 11, 2010.

Hong-An Truong is an artist and writer based in New York and North Carolina. Her photographs and videos have been shown across the U.S. and in Seoul, South Korea. Her work was screened at the PDX Documentary and Experimental Film Festival in 2009. Recent shows include Art in General, Gallery 456 at the Chinese American Arts Council, both in New York, a screening at DeSoto Gallery in Los Angeles, and a solo show at the New Media Gallery at the John Hope Franklin Center at Duke University. Currently her work can be seen in a group show at the International Center for Photography in New York. Truong received her MFA at the University of California, Irvine, and was a studio fellow in the Whitney Independent Study Program. She is the current recipient of a BRIC Media Fellowship from the Brooklyn Arts Council and will begin teaching at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill this fall, 2010.

Recommended citation: Hong-An Truong and elin o’Hara Slavick, “War, Memory, the Artist and The Politics of Language,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 31-2-10, August 2, 2010.

See also: To the end of the world with Noam Chomsky and elin o’Hara Slavick

Articles on related subjects

*Asterisked items relate to visual and exhibit representations of war and atrocities

Ishikawa Yoshimi, interviewed by Kono Michikazu, Healing Old Wounds with Manga Diplomacy. Japan’s Wartime Manga Displayed at China’s Nanjing Massacre Memorial Museum

Honda Katsuichi, From the Nanjing Massacre to American Global Expansion: Reflections on Japanese and American Amnesia

*Jeff Kingston, Nanjing’s Massacre Memorial: Renovating War Memory in Nanjing and Tokyo

David McNeill, Look Back in Anger. Filming the Nanjing Massacre

Takahashi Yoshida, The Nanjing Massacre. Changing Contours of History and Memory in Japan, China, and the U.S.

Herbert P. Bix, From Nanjing 1937 to Fallujah 2004: War Crimes in Perspective

Howard Zinn with Yuki Tanaka, Hiroshima: Breaking the Silence

Richard Falk & Yuki Tanaka, The Atomic Bombing, The Tokyo War Crimes Tribunal and the Shimoda Case: Lessons for Anti-Nuclear Legal Movements

Daniel Ellsberg, Building a Better Bomb: Reflections on the Atomic Bomb, the Hydrogen Bomb, and the Neutron Bomb

Richard Minear with Mark Selden, Misunderstanding Hiroshima

*Michelle Mason, Writing Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the 21st Century: A New Generation of Historical Manga

*Shinya Watanabe with Jean Downey, Into the Atomic Sunshine: Shinya Watanabe’s New York and Tokyo Exhibition on Post-War Art Under Article 9

*Nakazawa Keiji interviewed by Asai Motofumi, Barefoot Gen, the Atomic Bomb and I: The Hiroshima Legacy

Mark Selden, Living With the Bomb: The Atomic Bomb in Japanese Consciousness

*Greg Mitchell, Weapons of Mass Destruction, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the Atomic Testing Museum

*John W. Dower, Ground Zero 1945: Pictures by Atomic Bomb Survivors

Peter J. Kuznick, Defending the Indefensible: A Meditation on the Life of Hiroshima Pilot Paul Tibbets, Jr.

Peter J. Kuznick, The Decision to Risk the Future: Harry Truman, the Atomic Bomb and the Apocalyptic Narrative

Ben Kiernan and Taylor Owen, Roots of U.S. Troubles in Afghanistan: Civilian Bombing Casualties and the Cambodian Precedent