Hiroshima: A Visual Record

広島ーー視覚的記録

elin o’Hara slavick

On August 6, 1945, the United States of America dropped an atomic bomb fueled by enriched uranium on the city of Hiroshima. 70,000 people died instantly. Another 70,000 died by the end of 1945 as a result of exposure to radiation and other related injuries. Scores of thousands would continue to die from the effects of the bomb over subsequent decades. Despite the fact that the U.S. is the only nation to have used atomic weapons against another nation, Americans have had little access to the visual record of those attacks. For decades the U.S. suppressed images of the bomb’s effects on the residents of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, as they did the images of sixty-four other cities that were firebombed in the final months of the war. And as recently as 1995, on the fiftieth anniversary of the atomic bombing, the Smithsonian Institution cancelled its exhibition that would have revealed its human effects and settled for the presentation of a single exhibit: the Enola Gay, the plane that dropped the bomb on Hiroshima.

For the victims, the situation is quite different. Hiroshima is now a City of Peace. Everywhere there are memorials to this catastrophic event that inaugurated the Atomic Age and monuments to the commitment to peace at the center of the Hiroshima response to war. A-bombed trees continue to grow and A-bombed buildings remain – marking history, trauma and survival. The city is dotted with clinics for the survivors and their special pathologies. Names are added each year to the registry of the dead as a result of the bomb. This registry is central to the large Peace Memorial Park that houses the Peace Memorial Museum, countless monuments, and a Hall of Remembrance, all situated in the heart of downtown Hiroshima. It has been over 60 years since the atomic bomb was dropped, but the A-bomb is everywhere in Hiroshima.

The enormity of Hiroshima challenges the artist, especially the American artist, in ethical and formal ways. For several years I worked on a series of anti-war drawings of places the United States has bombed, subsequently published as the book Bomb After Bomb: A Violent Cartography, (Charta, Milan, Italy, 2007), with a foreword by former U.S. air force bombardier and radical historian Howard Zinn. After making relatively abstract drawings from the bomber’s aerial perspective that include no people – civilians, victims, soldiers or otherwise – I have now been on the ground, 60 years after the bomb was dropped, but still, on the ground. Hiroshima suddenly became real to me.

Hypocenter in Hiroshima, Japan, 1945, from the series Protesting Cartography: Places the United States has Bombed, 1999-2005.

Carol Mavor writes in her essay Blossoming Bombs in Bomb After Bomb: A Violent Cartography, “In slavick’s Hypocenter in Hiroshima, polka dots of alabaster wool hover over a pink and grey map speaking a silent sign language hailed by the city’s blasted center. At the center there was no sound, but slavick has prettily and eerily marked the silence with the sound of color. The pattern of slavick’s Hypocenter cartography could echo the decorative scheme of any woman’s fashionable forties American dress, of those women who sat at home unknowingly day dreaming as Little boy was dropped, as children (as every bit as precious as their own) vanished in Hiroshima, or left their childish shadows, their little prints, on the stone steps of their school. The writer Marguerite Duras, in her screenplay Hiroshima mon amour, has referred to these shadow-images, like the famous nebulous silhouette of the unknown person who sat on the steps waiting for the Sumitomo Bank to open, only to vanish with the light of the bomb, as “deceitful pictures.”

Sidewalk and Curb at the Hypocenter, 2008. “Carried to Hiroshima from Tinian Island by the Enola Gay, a U.S. Army B-29 bomber, the first atomic bomb used in the history of humankind, exploded approximately 580 meters above this spot. The city below was hit by heat rays of approximately 3,000 to 4,000°C, along with a blast wind and radiation. Most people in the area lost their lives instantly.”

Howard Zinn writes in Hiroshima, Breaking the Silence, “A Japanese schoolgirl recalled years later that it was a beautiful morning. She saw a B-29 fly by, then a flash. She put her hands up and “my hands went right through my face.” She saw a “man without feet, walking on his ankles.”

I never expected to live in a building built by the U.S. military in 1947, after the atomic bomb was dropped—built for soldiers and American scientists to study the victims of my country’s crime. But there I found myself for the summer of 2008, perched on a hill overlooking the city. It is an old compound – a little rusty and abandoned even though plenty of people still work there. Originally it was called ABCC (Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission). In the 1970’s it was renamed RERF (Radiation Effects Research Foundation) when it became a joint operation with the Japanese. I was there because my husband, an epidemiologist, was studying the A-Bomb data, to see if his assumption was correct—that things were much worse than reported.

The Japanese people had this to say about ABCC in the 1950’s, “They examine us but they do not treat us.” The people of Hiroshima do not like the fact that the compound is up there – out of the way, difficult for survivors to get to and on precious land. As far as I can tell, the American government has no plans to move it.

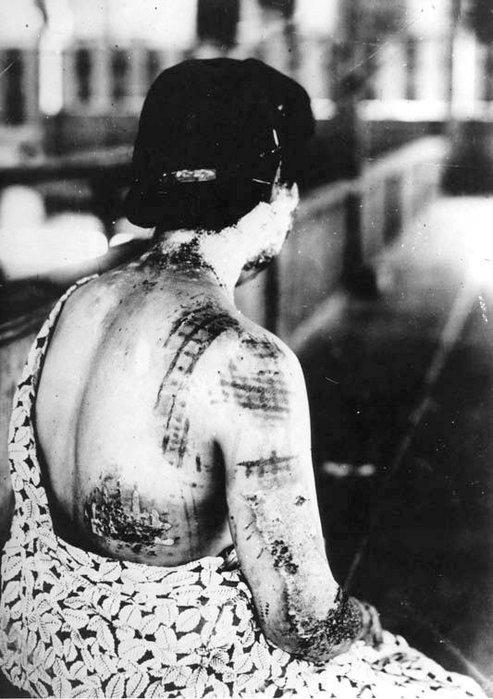

Mavor continues, “After seeing the cartography of violence in slavick’s flowery abstractions of ghastliness, I managed to get my hands on a copy of Iwasaki’s film, Hiroshima-Nagasaki, August, 1945. I watched its horrors on my home television, turning it on and off, as my eight-year-old son came in and out of the house. I did not want to scar him with the image of the Hiroshima woman whose skin had been dermagraphed by the design of her kimono from the heat flash of the bomb. The dark areas drew more heat and severely burned her skin. She was violently mapped with abstractions. She, too, was horribly photographed.”

Woman with Burns Through Kimono, 1945, Kimura Gon’ichi, Peace Memorial Museum

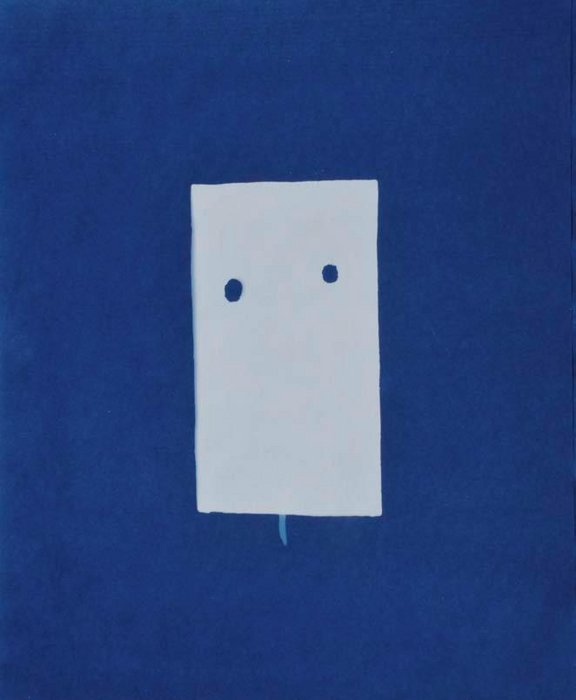

Ishiuchi Miyako, chromogenic print of an A-bombed dress from Hiroshima: Strings of Time, 2008

Coincidentally we lived right next to the Hiroshima City Museum of Contemporary Art that mounted an extraordinary exhibition while we were there of Ishiuchi Miyako’s Hiroshima: Strings of Time – a series of large color photographs of A-Bombed clothing from the Peace Memorial Museum’s collection. Miyako only chose things that were once in contact with human skin. She photographs these ghostly things on a light table to illuminate the fabric, stains and ruptures, holes and sutures. It is disturbing and oddly fulfilling to find so much beauty in the rendering of horror with spectacular aesthetics.

Miyako writes, “The objects that remained in the city after being subjected to a military and scientific experiment do not speak, they merely exist, but despite the horrors of the details, I found myself overwhelmed by the bright colors and textures of these high-quality clothes. It is difficult for a human being to survive for even one hundred years, but these objects have been bestowed with a longer existence. As parts of the largest scar the world has known, they will outlive us all, and never grow old.”

Schoolgirls having a picnic on the Motoyasu-gawa Riverbank in Peace Memorial Park, Hiroshima, 2008.

These girls are like the girls who wore those beautiful dresses.

I cried several times while in the Peace Memorial Park – once while listening to the audio at the Tower for Mobilized Students, and throughout the two devastating documentary films in the museum: A Mother’s Prayer from 1990 and Hiroshima and Nagasaki: The Harvest of Nuclear War from 1982. I am dumbstruck by the words, “In the searing flash, I became a picture. Blasted by the heat, I melted into the wall. Blasted by the wind, you disappeared into the earth.” Both films have footage of a two year old girl heaving and crying out for her dead mother and roving shots of the dead, of skulls, charred bodies, keloids, deformities, destroyed cities, everything completely obliterated and yet, and yet, the miracle of a kind of survival for some. A young girl fans the ashes of her father in an urn, wishing to cool him. He was a fisherman and died three days after being exposed to the atomic tests on the Bikini Atoll. In Hiroshima, all things atomic are connected. Sadako, the girl who died of leukemia while folding thousands of her medicine wrappers into paper cranes is tied to the girl who was damaged by radiation at the moment of conception and who would never understand the damage. There is no cure for the atom bomb.

Sculpture of Sadako Sasaki at the top of the Children’s Peace Monument, 2008. Teenager Sadako Sasaki died of A-Bomb disease – leukemia – in 1955. She had hoped to recover by folding a thousand paper cranes to bring good luck – a popular belief. Sadako folded over a thousand cranes but still she died. Students all over the world contributed to the funds for this monument to comfort Sadako’s soul and their own and to express their desire for peace. She holds up a large crane, about to take flight. Here she is seen on a rainy day by looking up through one of the many glass display rooms filled with paper cranes in her honor.

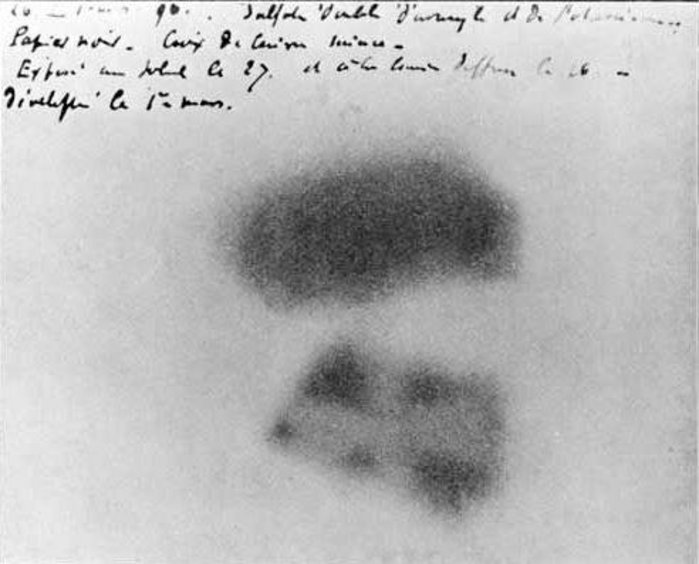

The history of the atomic age is intertwined with that of photography. The discovery of the radioactive energy possessed by natural uranium was via a photograph that launched the nuclear age. In 1896 Henri Becquerel placed uranium on a photographic plate, intending to expose it to the sun. However, because it was a cloudy day, he put the experiment in a drawer. The next day he decided to develop the plate anyway. To his amazement he saw the outline of the uranium on the plate that had never been exposed to light.

Image of Henri Becquerel’s photographic plate that has been fogged by exposure to radiation from uranium salt, 1896. The shadow of a metal Maltese cross placed between the plate and the uranium salt is clearly visible.

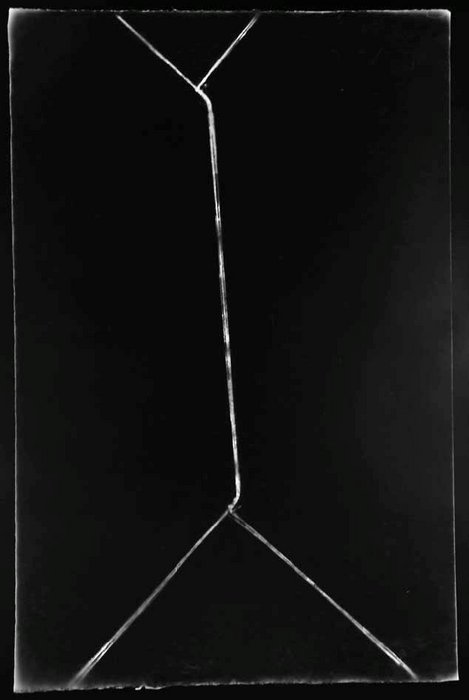

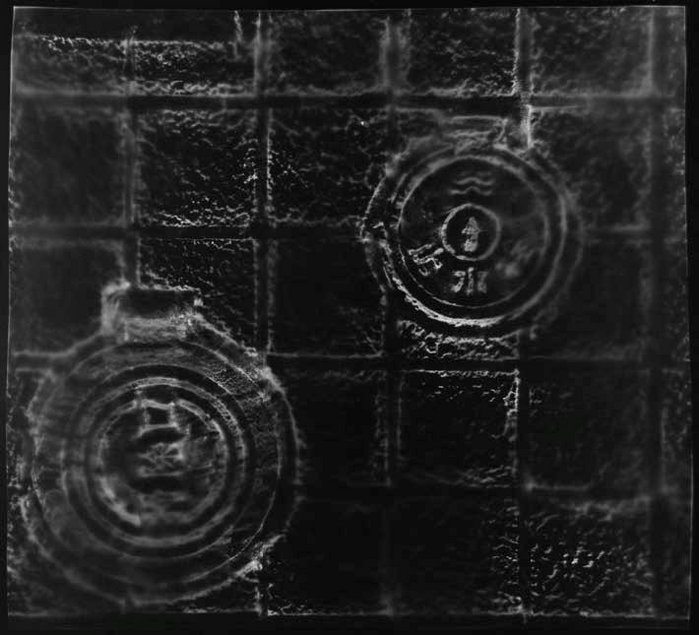

Silver gelatin contact print made from an autoradiograph – a sheet of x-ray film that captures radioactive emissions from objects, 2008. Here, a fragment of an A-bombed tree from the Peace Memorial Museum’s archive was placed on x-ray film in light-tight conditions for ten days.

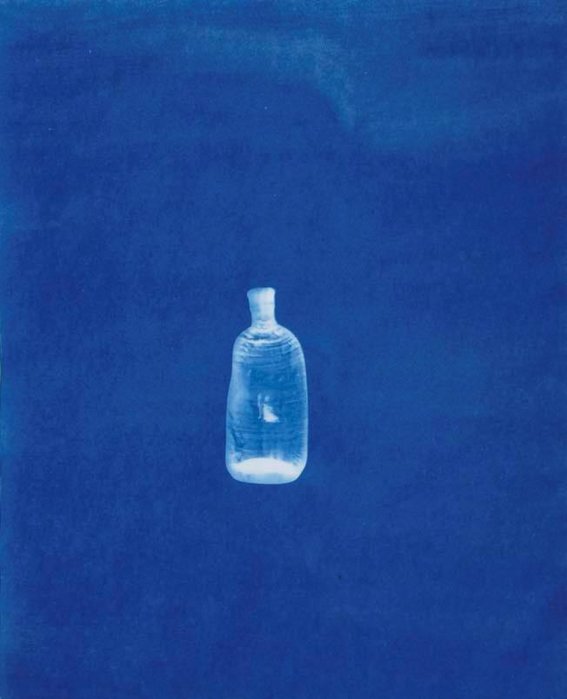

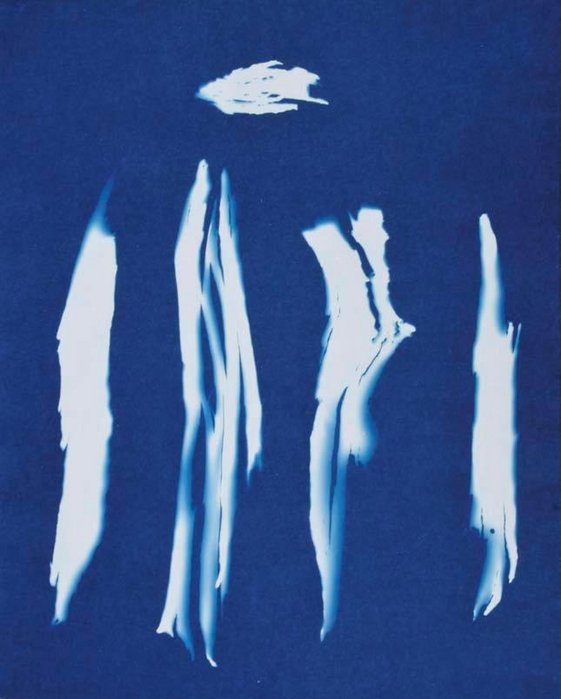

Becquerel correctly concluded that the uranium was spontaneously emitting a new kind of penetrating radiation and published a paper, ‘On visible radiation emitted by phosphorescent bodies.’ Following in the steps of Henri Becquerel, I worked in close collaboration with the staff of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum for 3 months during the summer of 2008. I commenced a pilot project on the use of autoradiography (capturing on x-ray film radioactive emissions from objects), cyanotypes (natural sun exposures on cotton paper impregnated with cyanide salts), frottages (rubbings) and subsequent contact prints from the frottages, and traditional photography to document places and objects that survived the atomic bombing. The Peace Memorial Museum’s collection holds over 19,000 objects, many donated by A-bomb survivors. My work with autoradiography involved placing A-bombed objects on x-ray film in light-tight bags for a period of ten days. Surprisingly, or perhaps not, abstract exposures were made on the x-ray film -spots, dots, cracks and fissures. The lingering radiation in the metal and roof tile fragments, split and burned bamboo, tree knots and glass bottles, appears on the x-ray film much like Becquerel’s uranium on photographic plates. It could be background radiation. It is not a very controlled or scientific experiment. But then again, radiation is radiation. And radiation in Hiroshima takes on a whole different meaning regardless of its origin, doesn’t it?

Cyanotype of a fragment of a steel beam from the A-bomb Dome, 2008. The A-bomb Dome is the ruin of the 1915 Secession style Hiroshima Industrial Promotion Hall. It is preserved as an appeal for world peace and as a witness to the horror of nuclear weapons.

Cyanotype of a bottle deformed by the A-bomb, 2008. Placing the bottle directly on cotton paper impregnated with cyanide salts and exposing it to the hot afternoon sun for about ten minutes made this blue sun print.

I am stunned by the footage in those documentary films of grasses, flowers and ladders, and yes, even people, burned white or black onto the surface of wood and stone ¬negative shadows, erased things, imaged absences, atomic ghosts.

The process and problem of exposure is central to my project. Countless people were exposed to the radiation of the atomic bomb. To this day, they say that someone in their family was “exposed” to the bomb. Now I am exposing these already exposed A-bombed objects on x-ray film, but this time, it is the radiation within them that is causing the exposure. The cyanotypes of exposed objects taken briefly out of the vaults of the Peace Museum’s collection to be exposed to the sun, render the traumatic objects as white shadows, ghostly silhouettes—like Anna Atkins botanical cyanotypes from the 1800s but with a violent force. I am oddly satisfied with the discovery of the blank shadows of the ragged aluminum lunch box and round canteen, the slender hair comb with one tooth missing and deformed glass bottles amid the deep and uneven cyanotype blue. The cyanotypes produce haunting images of objects that survived the bombing, evoking those that vanished.

Cyanotype of an A-bombed Canteen, 2008.

Cyanotype of dead Hiroshima Flowers, 2008

I am fortunate to have had access to these materials and bothered by the incalculable absence that these things mark and hold; aware that once again, these objects are being exposed—not to radiation, but from radiation and to light. The cyanotypes render these damaged objects in soft white forms, much like the white shadows cast by incinerated people and bridge railings, ladders and plants at the time of the A-bomb. Criminal absence has been made visibly present by itself. I am utilizing exposures to make visible the unseen, to reveal what is denied and hidden.

The Japanese people have attempted to make public maps from memory of the destroyed neighborhoods at ground zero – neighborhoods that were once full of artists and doctors, actors and writers, children and teachers, workers, peddlers and families. I am troubled by the name of the park – “Peace Memorial Park” – as if peace has vanished and we can only remember it, not live it, and I suppose that for the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, this is ultimately and absolutely true. It is ironic that a brutal slaughter is the reason for this park where children sing and have picnics and tourists come with paper cranes and cameras. Simultaneously, I am awed by the strength and purpose of the Japanese people to commemorate all those lost lives, to pay homage to their city that was – all in the name of peace, not revenge.

The old Fuel Hall and City Planning Office sits at one end of the Motoyasu-bashi Bridge that spans the Motoyasu-gawa River, 2008. Mr. Nomura Eizo survived the A-bomb in this building because he went down to the basement to retrieve some paperwork. When he came upstairs all he could see was a burning hell. He died in 1982 at the age of 84. The old Fuel Hall is now the Peace Memorial Park Rest House.

Toyofumi Ogura writes in his Firsthand Account of the Bombing of Hiroshima, Letters from the End of the World, “I imagine that the sight of Hiroshima so horribly transformed will stay with me for the rest of my life. Little more than 3 hours had elapsed since the blinding flash, and in those hours Hiroshima had ceased to exist. Japan’s 7th largest city, with a population of 400,000, had disappeared. Known as a water metropolis because it was built on the white deltas formed by the clear waters of seven rivers, the city was now burned and dry. It turned out that those 3 hours were really no different than an instant. I learned later that the city’s transformation did take place instantaneously, at the moment of the bluish flash of light.”

A man washes his feet in the Motoyasu-gawa River that was once blood red and filled with corpses, 2008. The river runs through downtown Hiroshima. The Rest House stands on the opposite riverbank.

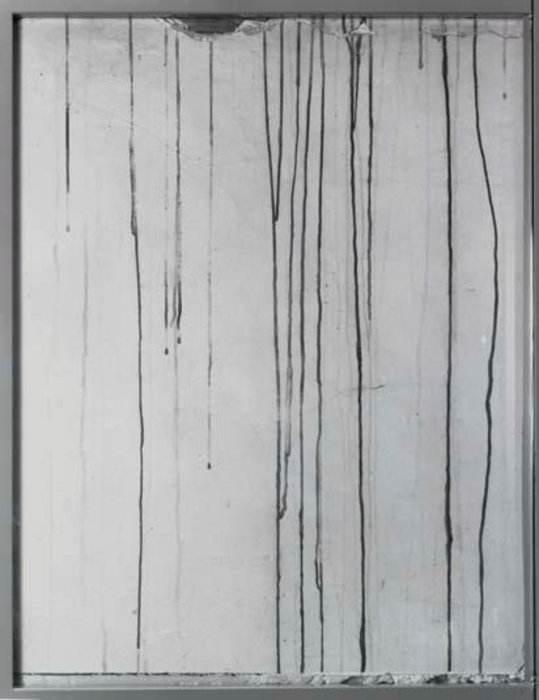

Silver Gelatin Contact Print of a frottage of one of the doors in the basement of the Rest House, 2008.

Black Rain on White Wall, Hiromi Tshucida, 1995. This chunk of wall is one of over 19,000 articles from the aftermath of the bomb that can be found in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum.

A detail of the wall in the old Fuel Hall basement, 2008.

Roland Barthes writes in Camera Lucida, “The person or thing photographed is the target, the referent, a kind of little simulacrum, any phantom emitted by the object, which I should like to call the SPECTRUM of the Photograph, because this word retains, through its root, a relation to “spectacle” and adds to it that rather terrible thing which is there in every photograph: the return of the dead…Photography is a kind of primitive theater, a kind of Tableau Vivant, a figuration of the motionless and made-up face beneath which we see the dead.”

Silver Gelatin Contact print of a frottage of keyholes in one of the basement doors in the Rest House, 2008.

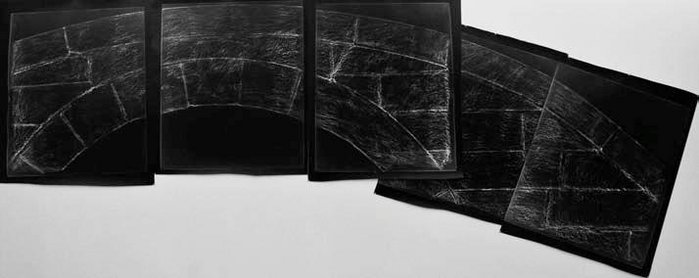

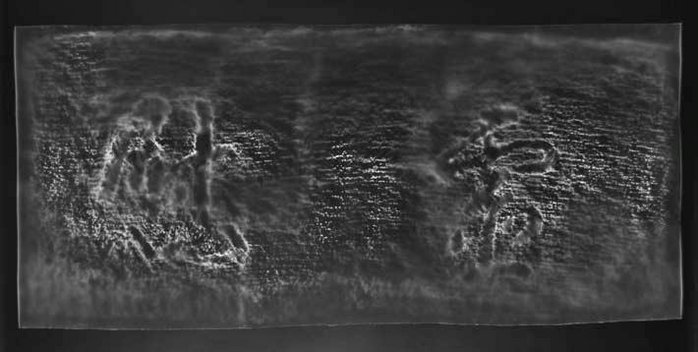

I am also making black crayon frottages, or rubbings, on Japanese paper of A-bombed places and things: the bridge that was the lone survivor in a traditional Japanese garden; a bank counter top, floor and vault; and trees, among other things. I was given permission to do rubbings and make photographs in the basement of the old Fuel Hall. I spent two days there, wearing the required hard hat to take pictures of the black-rain-like stains on the wall, the worn stairwell banister, the dark and damp room, the rusty door and empathetic origami offerings left for Mr. Nomura Eizo. I felt the lonely weight of survival. I made frottages of the old keyholes and broken columns, rusty doors and hallowed floor. The frottages are then exposed in the darkroom as ‘paper negatives’ used to make contact prints on photographic paper. The result is another ghostly trace, a negative index, almost as if the surface has been dusted with light or memory, or the subject has been x-rayed.

Silver Gelatin Contact Print of a frottage of the A-bombed Koko Bridge in Shukkeien Garden, 25ft x 6ft., 2009.

I walk over, again, to the Peace Memorial Museum and decide to go in this time with the hundreds of school kids. I can barely see the soft and thin clothing on display, the black rain on a white wall, the utensils and melted bottles. The schoolchildren take notes. I learn that the U.S. dropped the A-bomb to “justify expenditures”, that there were children called bomb orphans (who shined the shoes of westerners), and that “there is no such thing as a good war or a bad peace.” I also learn that Hibakusha say simply, “I met with the A-Bomb.” As of 2007, there were 251,834 Hibakusha in Japan, 78,111 survivors of the bomb still living in Hiroshima.

Schoolgirls looking at Sadako’s miniature paper cranes in the Peace Memorial Museum, 2008.

I am most struck by the disappearance of whole cities and peoples, structures and nature, not just by bombs and war, the A-bomb and natural disasters, but by deliberate and calculated progress, development, profit and growth. Most of the time, if I ignored the signs being in a language I do not understand, I could be anywhere – in New York or Lyon, Los Angeles or Charlotte.

Trees Behind the Hiroshima Train Station where hundreds of A-bomb orphans once lived, 2008.

Then there are the photographs themselves, still exposures of light upon matter and events. I made hundreds of exposures while in Hiroshima, digital and analog, color and black and white, images of survival and images of destruction. There is a large series of dandelion heads about to disappear into the wind, a small gesture in the midst of a profound event.

Hiroshima Dandelion, 2008.

This gesture hails back to the many flowers that blossomed shortly after the atomic bomb was dropped. As John Hersey writes in his unforgettable book Hiroshima, “The bomb had not only left the underground organs of plants intact; it had stimulated them. Everywhere were bluets and Spanish bayonets, goosefoot, morning glories and day lilies, the hairy-fruited bean, purslane and clotbur and sesame and panic grass and feverfew.” The blooming of flowers offered a false and fleeting hope to the victims and survivors of the A-bomb. And like this sign of regeneration, a dandelion vanishes, perhaps with a child’s breath of a wish, but usually it disappears without notice – small, wispy, fragile balls, tiny-stemmed and temporary stars. To me, the photographs of dandelions are as powerful and significant as the photograph of the hallowed basement and of the A-bombed gravestone of a government official. When the atomic bomb was dropped on Hiroshima, the stone ball on top of the gravestone was toppled, half buried in the ground. Engraved on the ball are the Japanese characters for sky and wind, but you can only see half of wind.

Hiroshima Gravestone, 200 meters from the hypocenter, 2008. This ruin in the Peace Memorial Park was the gravestone of Kunai Okamoto, a senior statesman of the Asano clan that controlled Hiroshima during much of the Tokugawa era. The top of the gravestone was hurled to the ground from the tremendous blast of the A-bomb. The words read sky and wind – wind being half buried in the ground.

I collected fallen leaves and damp bark from the A-bombed eucalyptus tree at Hiroshima Castle. I walked around to the back of the tree and saw it literally weeping thick burgundy tears, bleeding. I made a rubbing of the trunk. A Japanese man walked by and said “beautiful.” I also did a rubbing of the burlap rope tied around an A-bombed willow tree and snapped off a little branch to contact print on cyanotype paper. I rubbed the 1930’s wooden floor and walls pockmarked with shards of glass at the old bank – one of the only remaining buildings after the A-bomb – now an exhibition center. The show was of a million paper cranes heaped and hung and arranged in aisles. I collected leaves in various stages of decay to delicately render in gouache and to expose to the sun on cyanotype paper.

Cyanotype of bark from an A-bombed Eucalyptus tree, 2008.

Gouache of Hiroshima Leaves, 2008.

Cyanotype of Hiroshima Leaves, 2008.

Silver Gelatin Contact Print of a frottage of rope around an A-bombed Willow tree, 2009.

A-bombed Eucalyptus tree, weeping stigmata, 2008.

I hope to engage in ethical seeing, visually register warfare and address the irreconcilable paradox of making visible the most barbaric as witness, artist, and viewer. Susan Sontag asks the challenging question, “What does it mean to protest suffering, as distinct from acknowledging it?”

According to my tour guide, “There are 258,000 names of A-bomb victims registered under the cenotaph. Each year on August 6, new names are added. The Flame of Peace is not an eternal flame because it will only burn until nuclear weapons are abolished. Hiroshima has 20/20 vision—a vision of a nuclear weapons-free world 75 years after the A-bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. 2,000 cities outside of Japan participate in the annual conference of Mayors for Peace, an organization started in Hiroshima. During the 1970s and 80s Peace education was thriving. These days, Japan is becoming more militaristic and patriotic and the numbers of visitors to the Peace Park, especially of schoolchildren, are dropping.” I went to the Hall of Remembrance to hear a Hibakusha (A-bomb survivor), Okada Emiko, speak about her experience. She was 8 years old when she saw the sky blast and rip open and turn her world into ashes, death and poison. The following are scribbled notes as the translator spoke: “I am here today to speak about my A-bomb experience but also about what to do about our future. I was 8 years old when the bomb was dropped. In 10 seconds everything in a 2-kilometer radius from the hypocenter was burned. The winds from the blast, heat rays and radiation were the 3 elements that destroyed everything. Radiation was scattered in a 4-kilometer radius. 70,000 people died instantly. Another 70,000 died by the end of 1945.”

Hypocenter, 2008.

Silver Gelatin Contact print of a frottage of the sidewalk at the Hypocenter, 2009.

Hibakusha (A-bomb survivor), Okada Emiko continues, “August 5, the night before, many planes flew over. It was a sleepless night. All of us were dressed in clothes that had been altered from kimonos because kimonos were not suitable for work. All boys were dressed like soldiers. On the morning of the 6th there was an air raid warning but then it was lifted. We were all preparing for the day’s work. I heard the noise of a plane. I saw shiny airplanes flying over in the blue sky. With my 2 brothers I looked up and saw the shiny planes and thought, ‘oh, planes,’ and then there was an enormous flash; my mother was covered with blood from shattered glass. She took us and fled. In 10 seconds enormous flames came towards us. Those who didn’t die instantly tried to flee to the outskirts of the city, crying, yelling for help as they headed towards the mountains. Children were crying for their mothers, ‘mother, mother, mother,’ in desperation towards the mountainside. People were badly burned, flesh and bones exposed. What I remember about myself is I was very nauseous and vomited. I saw 2 horses that died with their intestines exposed. People were dying and calling feebly for help, ‘water, water’. There was a charred four year old but the eyeballs came out drooping and I could not tell if it was a boy or a girl.

Nobody knew what happened.

My family: my older sister had left home that morning with a cheerful goodbye. She was supposed to be near ground zero. She never came back and the city burned all night and was leveled. After the fires subsided, I saw nothing but wasted remains of buildings and I could see all the way to the Ugina port. My mother went out to search for my sister and saw bodies everywhere, including in all the rivers. The river was red. My mother tried almost 3 months to find her daughter, as far as Ninoshima Island (where some orphans were sent), to find some clues of her daughter, but there was no trace. After months of searching she became very sick. I think she had a miscarriage. We stayed in a bamboo grove. My brother had burns and maggots bred in his injuries. There was no medicine, no doctors, and no way to treat the injuries. The only treatment was powder made out of human bones. Myself, I had bleeding gums around the clock so my mouth was always sticky. My hair fell out. I was tired all the time and had no strength. We did know what it was. People said it was a poison.

In the rebuilding process, from the river and earth, many things have been dug out—belt buckles, buttons. Parents who lost children, old parents, rush to see with slight hope if they can find a clue of their children. These parents are in their 80s and 90s now. Today there are over 30,000 nuclear weapons in this world. Hiroshima and Nagasaki are not past events. They are about today’s situation.”

Detail of A-bomb Victim – the Monument of Hiroshima, students digging up A-bombed fragments from the Motoyasu Riverbank in the 1970s, 2008.

The hibakusha gives us each a paper airplane made by a bomb-orphan, now in his old age. When you spread the plane’s wings a paper crane rests on the plane’s spine—swords into plowshares, bombs into birds.

Paper Bomber Plane made by an A-bomb Orphan in his old age, 2009.

A-bombed glass at the Honkawa Elementary School Peace Museum, 2008.

Historical photograph of the playground at Honkawa National School after the A-bomb, 1946.

The Honkawa National School was almost completely destroyed by the A-bomb and is now a peace museum full of: paper cranes; scratched and cracked walls like Cy Twombly paintings; glass, buttons, wood, buddhas, ceramic and cloth artifacts in vitrines; broken switchboards; scarred stairs; repaired ceilings; buckets of rusty objects. When I walk outside of the dark and thick interior, I am blinded by the late July sun beating down on the new white school surrounded by palm trees and sculptures. Hiroshima will never be finished or resolved. It is a constant and eternal place. I could make art here forever.

Silver Gelatin Contact print of a frottage of a memorial to those who died on the island of Ninoshima, twenty minutes by ferry from Hiroshima, where contaminated horses were sent to be cremated, sick soldiers and orphans were sent to be quarantined and an orphanage was built, which is still in use today, 2009.

I learned from my tour guide that these Japanese characters I had seen on many memorials throughout Hiroshima, including the one above, translate as Comfort Souls. The Japanese use this term to comfort the souls not only of the dead but also of the living. Barthes writes in Empire of Signs, “This city can be known only by an activity of an ethnographic kind: you must orient yourself in it not by book, by address, but by walking, by sight, by habit, by experience; here every discovery is intense and fragile, it can be repeated or recovered only by memory of the trace it has left in you: to visit a place for the first time is thereby to begin to write it: the address not being written, it must establish its own writing.”

Again Sontag, “Remembering is an ethical act, has ethical value in and of itself. Memory is, achingly, the only relation we can have with the dead… Photographs of the suffering and martyrdom of a people are more than reminders of death, of failure, of victimization. They invoke the miracle of survival.”

Detail from the A-bombed Motoyasu Bridge, 130 meters from the hypocenter, 2008. “The blast from the atomic bomb struck the Motoyasu bridge, blowing the railings on both sides of the bridge outward, throwing them into the river. As it was directly under the blast’s center, the bridge itself was spared major damage, making it an important structure from which the precise location of the hypocenter could be measured. Two outer pillars from the original bridge are preserved here as a witness to history. – May 25, 1992, The City of Hiroshima”

May we know a better world.

Acknowledgments

Some of this essay is taken from a blog I made while living in Hiroshima.

Some of this essay can also be found in Hiroshima: After Aftermath, Critical Asian Studies (June, 2009, cover and pages 307-328).

This work is made possible by the extremely valuable professional contacts and support I have been granted by the people of Hiroshima. These include Directors, Associates and Curators at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, Peace Culture Foundation, Center for Nonviolence and Peace, City Culture Foundation, World Friendship Center, Peace Institute, as well as the Museum of Contemporary Art. These organizations have given me access to their collections and resources, and facilitated my receipt of permission from Hiroshima City Hall to make photographs and frottages of certain A-bombed places and memorials. I would like to especially thank Steven Leeper, Chairman of the Hiroshima Peace Cultural Foundation for his extreme generosity in allowing me to work in the Peace Memorial Museum with the help of his inspiring colleagues. None of this would be possible without the solidarity of my true comrade, David Richardson, with whom I am trying to raise two pacifist children.

Bio

elin o’Hara slavick is a Distinguished Professor of Art at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She received her MFA in Photography from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago and her BA in poetry, photography and art history from Sarah Lawrence College. Slavick has exhibited her work in Hong Kong, Canada, France, Italy, Scotland, England, Cuba, the Netherlands and across the United States. She is the author of Bomb After Bomb: A Violent Cartography, (Charta, 2007).

Recommended citation: elin o’Hara slavick, “Hiroshima: A Visual Record,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 30-3-09, July 27, 2009.