In Search of Peace: A New Generation of Japanese Encounters the Asia-Pacific War

Edan Corkill

I Words of War – Some young Japanese are striving to record the wartime memories of aging former combatants before they are forever lost to posterity

In among the familiar roll call of memorial services, television specials, peace ceremonies and other events in Japan planned to coincide with next month’s 64th anniversary of the end of World War II, one stands out for its unlikely involvement of youth.

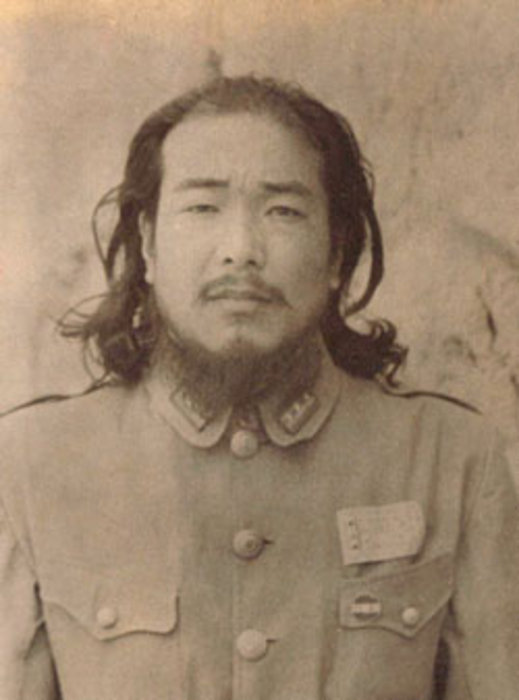

Nagatomi Hiromichi (front row, center), who served with the Tokumu Kikan (Special Services Section) in China, pictured with comrades in arms. He is one of more than 200 ex-servicemen who 32-year-old Sinitirou Kumagai has interviewed. Kumagai Sinitirou

Made by a director in his 20s, a documentary film titled “Hana to Heitai” (“Flowers and Troops”) will open at Image Forum in Shibuya, central Tokyo, and shortly after at other cinemas around the country.

The film comprises interviews with six former Imperial Japanese Army soldiers who opted, at war’s end, not to return to the country for which they had fought and so many of their compatriots had died.

In most cases, after escaping from their defeated military units, or from prisoner-of-war camps, they eked out a living with local villagers before eventually settling down, acquiring in due course jobs, wives, children and then, in the fullness of time, grandchildren.

Fascinating, certainly; but what’s really unusual about the film is that its director, Matsubayashi Yojyu, was in his 20s when he made it.

Interesting, too, is the fact that Matsubayashi is by no means an exception.

It turns out that, over the last few years, quite a few of his contemporaries have been reaching out to veterans of Japan’s mid-20th-century military exploits.

Generation-wise, of course, these budding historians are the veterans’ grandchildren, and as such they are likely the last people who have a chance to know and speak with them directly. Young enough to know very little of the war, they are also old enough to be able to ask.

As well as Matsubayashi, who is now 30, The Japan Times spoke to Sinitirou Kumagai.

For around 10 years, the 32-year-old has been recording the experiences of former soldiers who fought in China.

Then there is 31-year-old Jin Naoko, who has spent much of the last five years interviewing people who were on both sides of the fighting in the Philippines.

Intriguingly, though, none is particularly interested in using those battle tales for overtly moral or political ends. They are not out to administer parting condemnations for acts committed decades ago by the rapidly thinning ranks of their interviewees, nor do they want to pressure individuals into apologizing. Likewise, they do not marshal the testimonies they collect in an attempt to resist, for example, the current gradual watering down of Japan’s war-renouncing Constitution.

No, these level-headed observers are simply interested in recording and preserving the kinds of first-hand experiences that no other Japanese alive today has had.

The old soldiers appreciate the nonjudgmental, nonconfrontational approach, and in many cases they feel comfortable enough to reveal more than they ever have before. The interviewers’ genuine ignorance about what actually happened during the war also works in their favor, facilitating — necessitating, even — some extraordinarily frank exchanges.

But what else is motivating these young interviewers?

Two say that their experiences traveling in Asia set them on their current paths, after TV programs and the 1997 Asian financial meltdown helped make travel to the region both attractive and cheap in the late 1990s.

They got more than they bargained for. Talking to their Asian neighbors, the young travelers were made to realize for the first time that their own identities as Japanese were largely determined by a war about which they knew very little.

Matsubayashi, in particular, says his documentary film is an attempt to understand what exactly flashes across the mind of a Thai or a Filipino or a Chinese or a Korean, for example, when he utters the phrase: “I’m from Japan.”

Meanwhile, several other factors have predisposed these members of a war-divorced generation to take an interest in soldiers’ experiences.

All three mentioned the death in 1989 of Emperor Hirohito (posthumously known as Emperor Showa), and Prime Minister Hosokawa Morihiro’s apology for military aggression issued in 1993 — both of which dominated TV screens at a time when they were young enough to be still formulating their own opinions.

Still, it’s important not to get carried away in extrapolating broad generational trends. These are, after all, the experiences of just three young Japanese. And as Matsubayashi is quick to point out, he doesn’t harbor great hopes that vast numbers of his contemporaries will come to see his film — not like they would a Hollywood blockbuster, anyway.

There are at least two public institutions in Japan engaged in collating the kinds of oral histories that Matsubayashi, Kumagai and Jin are amassing. The national government- funded Shokei-kan, in Tokyo’s Kudanshita district, deals with the accounts of soldiers who became sick or wounded during the war; while Saitama Prefecture’s Peace Museum of Saitama in Higashi-Matsuyama looks at wartime experiences in general, including those of soldiers in battle.

However, thanks to the efforts of concerned young Japanese such as Matsubayashi, Kumagai and Jin as well, the country now has an extra rich vein to tap if it feels the need to dig deeper into the experiences that its wartime generation was put through all those years ago.

II China vets shock archivist with ‘horrible things they did’

In 1999, Kumagai Sinitirou dropped out of university, got on his motorbike and set out to begin what he now calls his “life work” — traveling from one end of Japan to the other to record the testimonies of former soldiers stationed in China between the 1930s and the end of World War II in 1945.

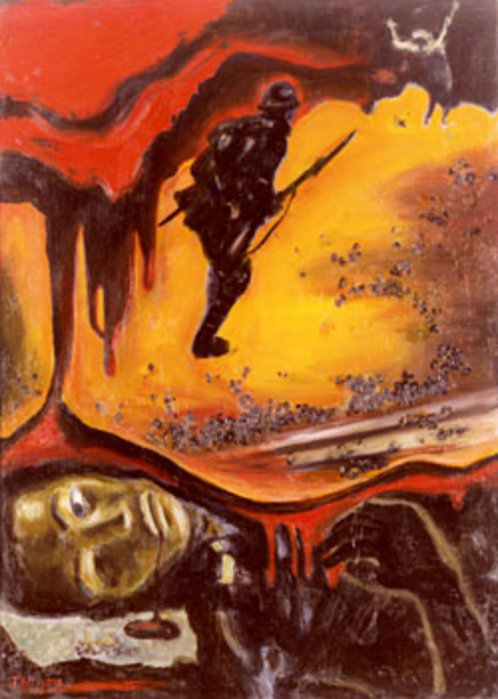

Hiyama Takao was a war artist with the Imperial Japanese Army in China. After the war he became an art teacher and also made pictures depicting his experinces on the front lines. Before he died in 1988, he left dozens of his paintings to Chukiren, a network for returnees from China. Kumagai Sinitirou

Kumagai, now 32, first became aware of those veterans when a friend gave him a copy of a magazine called Chukiren, which publishes the recollections of former soldiers who are members of a group called the Chugoku Kikan-sha Renraku Kai (Network of Returnees from China).

Kumagai said he was shocked to discover how, 70 years ago, normal young Japanese citizens like himself had been turned into monsters.

“The veterans are all normal people. They are good people. But when you read their stories, you realize they did some horrible things — really horrible things,” he explained.

Kumagai, who had his own share of problems — constant fighting and smoking saw him expelled from high school — decided to help the old soldiers publish their testimonies. Many were in their late 80s and were determined to “tell all” before they died, he explained.

Unlike most young Japanese who record the testimonies of former soldiers, Kumagai has not spent a lot of time overseas. Nevertheless, he understands his work is crucial for improving Japan’s regional ties.

“This was a war that Japan conducted overseas, so the general population here simply doesn’t know what happened,” he said.

The Chinese and Koreans, of course, remember, he said. “Unless the Japanese people know what the Japanese army did, we can’t hope to communicate properly with them.”

Of the 200-plus former soldiers who Kumagai has interviewed so far, the testimony of Nagatomi Hiromichi is particularly shocking.

Nagatomi was a direct student of Toyama Mitsuru, one of the most ardent proponents of the Pan-Asianism movement on which Japan’s expansionist polices were based.

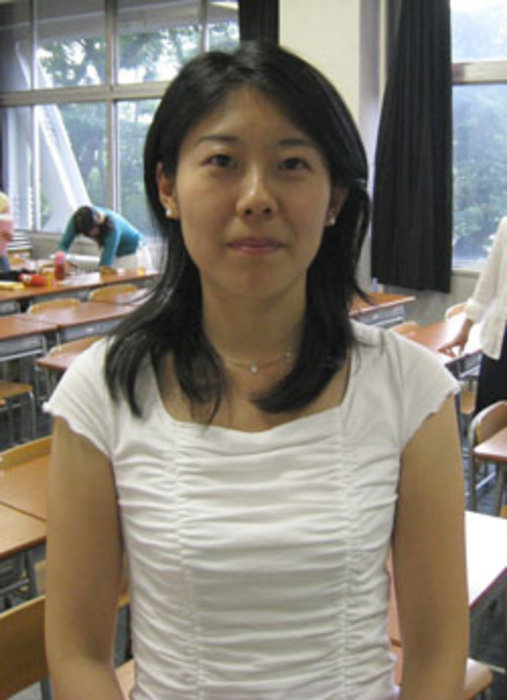

For 10 years, Kumagai Sinitirou, 32, has been recording the testimonies of former Japanese soldiers who served in China. Edan Corkill

Nagatomi was made a member of the Tokumu Kikan (Special Services Section), an elite group tasked with a variety of missions, including intelligence- gathering and various kinds of counter- insurgency work.

“I was training Chinese spies,” he told Kumagai. “We would capture Chinese farmers to seek information from them about the enemy. . . . We put the Chinese we caught in cells, didn’t give them food, made them go to the toilet in their cells until they reeked, beat them with clubs, tortured them using water and fire and, later on, killed them in vacant land behind the cells. . . . In this way, I personally killed well over 100 Chinese people.”

Before dying in 2002, Nagatomi gave Kumagai several old photographs and records of his service. In many of them he is seen with a long beard and wearing civilian Chinese clothes — trademarks of an undercover agent. Other interviewees have given Kumagai paintings they made to try to come to terms with what they did.

The testimonies of former soldiers who fought in China are often the subject of debate. After Japan’s defeat, many were detained in China, for up to six years, and were made to detail and recant their past deeds.

“When they came back to Japan,” explained Kumagai, “people started saying that they must have been brainwashed (by the Chinese), because they all seemed to express their remorse in similar ways.”

But Kumagai denies the testimonies he records are tainted.

“If it was brainwashing, it has lasted for 60 years, so it was amazingly effective,” he laughed dismissively.

“The problem with the people who talk about brainwashing is that they jump from there to the conclusion that we shouldn’t listen to these men at all,” he said.

Nagatomi Hiromichiin the guise of a Chinese (Left), while serving in the Japanese military’s Special Services Section in China in the 1930s, and in a Tokyo nursing home (Right) before his death in 2002. Kumagai Sinitirou

“That is not right. Maybe they were brainwashed, but we still have to listen to what they are saying.”

Since 2002, Kumagai has been conducting his interviews under the auspices of the Fujun no Kiseki wo Uketsugu Kai (Association to Carry on the Miracle of Fushun). Named after the location of one of the internment camps where Japanese soldiers were allegedly brainwashed, the group comprises about 400, mostly young, members.

Kumagai said he believes the veterans find it easier to talk to young people.

“When I first went to Chukiren, they were thrilled that a young person wanted to help them out,” he recalled.

“They can assume we know nothing about war, that we have no idea why they went to war or what they did there. They want to explain it,” he said. “They want to make us understand.”

Kumagai never met either of his grandfathers, who both died before he was born.

However, he says that his mother’s views have influenced him.

“She was born in Manchuria, so she had to be repatriated after the war,” he explained. “She hates war.”

His mother also hated the Soviet Union.

“Whenever we talk about politics, she always tells me to stay away from the Reds,” he said.

Kumagai put his parents at ease considerably around two years ago when he took a “day job” at publisher Iwanami Shoten.

“Up until then they were worried that I was just a delinquent riding around on my bike and talking to old men,” he laughed.

Kumagai said he wants to continue recording testimonies for as long as there are former soldiers alive who are willing to talk. He admitted, though, that now his wife is expecting a baby, spare time is becoming more and more difficult to find.

III Soldier who stayed on tells filmmaker how ‘We had to kill, kill, kill’

The most shocking moment in “Flowers and Troops,” a documentary film by Matsubayashi Yojyu, is when the young director leans close to one of his subjects — an 87-year-old former corporal in the Imperial Japanese Army — and says, “I’ve heard that some Japanese soldiers ate human flesh.”

Nakano Yaichiro, seen here with his Thai wife and his enlistment photograph, is one of six former Japanese soldiers who 30-year-old filmmaker Yojyu Matsubayashi tracked down in Thailand, where they have lived since most fled from prisoner-of-war camps at the end of World War II. Matsubayashi Yojyu

The former corporal, named Nakano Yaichiro, averts his eyes and, after a long pause, replies: “There are some things that I just can’t talk about.”

Nakano is one of six former soldiers interviewed in the film. What makes Matsubayashi’s question so poignant is that Nakano, like the five other interviewees, lives in Thailand — where they stayed at the end of the war to avoid being sent back to Japan after escaping from their defeated units or prisoner-of-war camps.

Matsubayashi’s blunt reference to cannibalism is his way of trying to pinpoint the experience that might have prompted these former soldiers to discard their country for good.

The film works both because, and in spite of, the director’s ignorance of his subject. During filming he was just 27 and 28 years old — now he’s 30.

“Because I was so young, I could honestly say that I didn’t understand what happened in the war. If I had been older, my questions would have angered the old soldiers because they would have thought I should know better,” the director said.

Matsubayashi traces his interest in Japan’s wartime past back to his time in primary school. When Emperor Hirohito (posthumously known as Emperor Showa) died in 1989, his teacher set him the task of interviewing relatives about their experiences in the war.

Matsubayashi Yojyu, who interviewed six former Japanese soldiers who stayed in Thailand after World War II for his film, “Flowers and Troops.” Edan Corkill

“I spoke to a friend’s grandfather. He fought in Burma, and I remember he said that things happened he couldn’t tell children. Those words stuck with me.”

Fast forward to 1999, and Matsubayashi was backpacking through Asia.

“I met lots of foreigners and realized they all had many bad impressions of the war. I met people in Singapore and Malaysia who don’t like the Japanese. I realized that when you’re Japanese, people look at you in lots of different ways,” he recalled.

A year later, Matsubayashi enrolled in the Japan Academy of Moving Images and came across director Shohei Imamura’s 1971 documentary, “Mikikanhei wo Otte” (“Pursuing the Soldiers Who Didn’t Return Home”), about a soldier who remained in Thailand after the war.

Nakano Yaichiro (left), a wartime army medic, sits at home with his wife in Mae Sot, Thailand. Matsubayashi Yojyu

“I wanted to know what really happened in the war,” Matsubayashi said. But he also felt that the nonreturnees could shed light on broader questions of what it means to be Japanese and the nature of Japanese society today.

“They have spent 60 years essentially without contact with Japan. I thought it would be interesting to hear their thoughts,” he said.

Matsubayashi said that the nonreturnees have generally been regarded as deserters, particularly by those soldiers who did return to Japan — like Matsubayashi’s own great uncle.

“But when I showed my great uncle photos of the former soldiers I met in Thailand, he said they looked like they have enjoyed very peaceful lives,” Matsubayashi recalled.

While their lives in Thailand do seem peaceful — in many cases they are surrounded by Thai wives, children and grandchildren — the soldiers Matsubayashi interviewed are still haunted by their wartime memories.

One of those, Isamu Sakai, recalls vividly his decision to remain in Thailand.

Former Japanese soldier Sakai Isamu (foreground), who died in 2007 at age 90, told filmmaker Matsubayashi Yojyu that he decided to remain in Thailand after the war when he heard a rumor that British planes had bombed a repatriation boat in the Strait of Malacca. He is pictured here in Mae Sot with his Thai wife shortly before he passed away. Matsubayashi Yojyu

“The information we got was not good. I heard that the Japanese ships (taking soldiers back to Japan) got bombed by a British plane in the Strait of Malacca. I lost all hope,” he said.

Like many others, Sakai was eventually welcomed into a village where he put to use his army-acquired skill as a mechanic.

Other former soldiers give accounts of battle so graphic they make you sit up in your seat.

“We had to kill, kill, kill,” barks 89-year-old Fujita Matsuyoshi through a toothless mouth. “We killed the Chinese children, their mothers, everything. There was an order that we had to kill them all if they were Chinese, good or bad. You understand? We had to kill the children.”

Fujita, who served in Singapore before being transferred to Burma, was the same soldier interviewed in Imamura’s 1971 documentary. He is well known in Japan for having built a memorial tomb and, over a 40-year period, buried the remains of more than 800 of his fellow soldiers.

“I built the memorial because the Japanese government wasn’t doing anything for the fallen,” he said.

He is also unequivocal about where blame lies for the war.

“It was a national operation, an order from the Emperor. We didn’t just go out there by ourselves. It was our Emperor Hirohito’s order. . . . If we didn’t follow an order, we’d get killed ourselves.”

Some former soldiers interviewed by Matsubayashi had been interviewed by Japanese journalists in the past. But he said he thought each had been more open with him than they had been with others.

“I think it’s because they are approaching death, and because I was so young,” Matsubayashi said.

Fujita’s testimony, in particular, is peppered with anxious confirmations that the Matsubayashi, who is in many of the shots, is comprehending what he’s hearing: “Do you understand what I’m saying?”

“There is this massive gap between my generation and his,” Matsubayashi said. “He knows we can never bridge that gap, but he still wants us to try to imagine what it was like — to understand why they did what they did.”

IV Bridge of sorrows – Videos help heal Japanese-Filipino wounds

When Jin Naoko tells former Japanese soldiers that the Filipinos they fought against during World War II are ready to forgive them, they simply don’t believe her.

Jin Naoko, left, Edan Corkill. Jin Naoko conducts a 2006 interview with a 91-year-old veteran of Japan’s occupation of the Philippines (right) Bridge for Peace

“They don’t expect to be forgiven,” said Jin. “They don’t think it’s possible that anyone could forgive them.”

For four years, Jin, 31, has ferried video messages back and forth between Japan’s former soldiers and their now-elderly victims in the Philippines — an attempt by her to bridge the gaping chasm in communication left by the violence of war.

She estimates she has interviewed around 70 Japanese and, in the course of five trips to the Philippines, dozens of Filipino nationals, too.

Asked why she started this kind of work, Jin recalled an experience in high school.

“I became friends with a German girl,” she said. “One day she told me that she didn’t want to be thought of as a German. I asked her why and she said because she was ashamed by what the Nazis had done.”

Jin explained that the Japanese education system doesn’t encourage students to see Japan’s history as something directly relevant to their own lives. “We were just made to memorize chronologies,” she said.

Motivated to confront her nation’s wartime history, Jin joined a study tour to the Philippines while she was a student at Aoyama Gakuin University in Tokyo in 2000.

“We toured some of the sites where fighting and massacres had occurred,” she said. “The Filipinos we met said straight out that they didn’t want to meet any Japanese. They asked us why we had come.”

Unperturbed, Jin and her fellow students listened intently to the old Filipinos’ stories.

“They told us so much that I wanted to give them something in return,” Jin explained.

In 2005, she did just that. Jin videotaped messages from former Japanese soldiers who had fought in the Philippines and delivered them to the same old Filipinos who had shared their experiences.

“They were really interested to see the videos,” she remembered. Some said they want to forgive the Japanese, she reported. Others were too upset to talk, and others still were just amazed that the Japanese still remembered the war so well.

“Many of the victims assumed that because Japan’s economy had developed so much, the Japanese had probably become too distracted to even think about the war,” Jin explained.

But her video messages showed the memories were still very much alive.

“Thinking about it now, we were like devils,” explained one former Japanese soldier. “Our commander ordered us: ‘They’re all guerrillas, so capture them all. Kill anyone who looks suspicious’.”

Others went into graphic detail; one described how he demanded food from two women he found hiding in an abandoned village and then raped them when they didn’t respond.

Jin explained that many of the soldiers find it easier to talk now that a lot of time has passed and they are nearing the end of their lives.

“One person said they could talk now for the first time because their commanding officer has died,” she recalled.

Others feel comfortable speaking to a young person.

“Many of them found their own children tended to criticize them for their involvement in the war,” Jin explained. That upset them, she said, because they never regarded their actions as being their own responsibility.

“I feel a lot of anger,” one soldier said. “At the time Japan was a country of militarism. It’s not like anyone became a soldier because they wanted to. I feel angry at those who were making the decisions. But who were they? Who was responsible? I don’t know.”

For their part, the Filipinos who talk to Jin are mostly forgiving. “The Philippines is, after all, a Christian country,” said Jin. But their stories are harrowing nonetheless.

“One soldier tried to take my baby cousin,” says one. “I held on to my cousin, but another put a gun in my side. I let go of the baby. They threw it up in the air and stabbed it with a bayonet.”

Jin’s work, which she does under the auspices of Bridge for Peace, a not-for- profit organization she started five years ago, is funded entirely by donations. She also holds down a day job.

While Jin initially focused on delivering messages back and forth between Japan and the Philippines, she soon began receiving many requests to show her videos at universities and other venues in Japan. Most surprising, she said, was the reaction of Japanese in their 40s and 50s, many of whom said it was the first time they had heard such war stories.

“It’s like, if people in their 50s don’t know about this, who does?” Jin exclaimed.

The lack of knowledge prompted her to redouble her efforts, and she now does two to three screenings a month in Japan in addition to her twice-yearly trips to the Philippines.

Jin said her thoughts are now focused on future generations.

“One day my children might come to me and say, ‘Mom, why didn’t you talk to those soldiers when you had the chance?’ I realized that because I am alive at the same time as them, I have a responsibility to listen to their stories and record them.”

This article was published in The Japan Times on July 26, 2009. Edan Corkill is a staff writer for The Japan Times.

Recommended Citation: Edan Corkill, “In Search of Peace: A New Generation of Japanese Encounters the Asia-Pacific War” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 32-3-09, August 10, 2009.