Tokyo Architects SANAA Score in US, Europe, Japan. Museum of Contemporary Art Opens in New York. Profile [Updated]

Edan Corkill

Nishizawa Ryue (left) and Sejima Kazuyo are the recipients of the Pritzker Prize for 2010, architectures highest honor.

Being an architect requires patience and endurance. For argument’s sake, let’s just say it’s 2002 and, as the highlight of your career to date, you win the competition to design a new art museum in one of the most prized locations in the world: Manhattan.

Nishizawa Ryue (left) and Sejima Kazuyo, Miura Yoshiaki photo

Time to crack open the champagne? Well, not quite. For architects, winning a competition is like taking the first, nervous step into a giant labyrinth — a labyrinth so vast and complicated that it might be years before you emerge at the other end.

Japanese architecture office SANAA — centered on its principals, Sejima Kazuyo (born 1956) and her protege-turned-business-partner Nishizawa Ryue (born 1966) — was set up in 1995. Old-timers? Well, after winning several high-profile competitions around the turn of the century (the New Museum in Manhattan included), it’s only in the last three or four years that they have finally begun to emerge from their labyrinths and present the world with the tangible fruits of their amazing architectural vision.

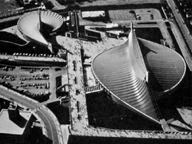

In 2004, the 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa, a large circular glass structure encasing a random sprinkle of square galleries, opened in that city in Ishikawa Prefecture in rural west-central Japan — and was promptly bestowed with the coveted Golden Lion award at the Venice Biennale for architecture.

Museum of Contemporary Art opened in Manhattan in December. Dean Kaufman photo

A year earlier, they completed their first major work in Tokyo: the elegant, glass curtain-fronted Christian Dior Building Omotesando in swanky Aoyama. In 2006, along with several buildings in Europe, they finished their first major commission in America, the Toledo Museum of Art’s Glass Pavilion, which stunned critics for being perhaps the world’s first genuinely transparent museum — both external and internal walls are made of glass.

By early last year it had become de rigueur in architectural circles to cite SANAA in lists of the most innovative architects in the world — alongside the likes of Frank Gehry, Rem Koolhaas, Renzo Piano, Tadao Ando and Toyo Ito.

Then came the Manhattan project: On Dec. 1, 2007 the New Museum of Contemporary Art opened to the public on the Bowery. Just before they headed off for those opening festivities, Sejima and Nishizawa sat down to talk about that project and how they got where they are.

SANAA stands for Sejima and Nishizawa and Associates, and it is the business you operate together. How did it start?

Sejima: When I set up my own office in 1987, Nishizawa was still a graduate student. He came and worked for me part time. When he finished his studies in 1990 he started working full time. After a while, when he started thinking about quitting to open his own office, I asked him if he’d work with me. Then we started SANAA (in 1995).

Nishizawa: Well originally, I had no intention of making a joint office with Sejima-san, but when I was about to quit we decided that for international competitions and large-scale domestic jobs it might be interesting to work together. So SANAA, the joint office, was created essentially to do those large jobs, such as the 21st Century Museum and the New Museum. I have my own office too, for smaller jobs: houses, shops, interiors.

So, Sejima was your boss and then became your partner, right?

N: She’s still my boss! It just looks like a partnership from the outside!

S: No, he was actually one of the first part-timers who came to work for me, so it was always like we were working together.

Can you describe your work process? Who actually comes up with the design ideas?

S: We get asked a lot if there is any division of the responsibilities between us. But there isn’t! Our way of working was never that one of us would lead with a sketch, and then our staff would work from that. Rather, from the very beginning, all our staff throw in ideas — How’s this? How’s that? — and then we decide on the direction through a process of discussion. But when it’s time to decide on something, Nishizawa and I do it together.

Your building for the New Museum in Manhattan has a very distinctive appearance — it’s like variously shaped boxes piled on top of each other. Where did that idea came from?

Nishizawa and Sejima with model of MCA

S: Well, the New Museum opened in 1977, and it was a museum that a group of curators had started themselves so they could do what they wanted, with more freedom. The building had to be free, new and different, like the art.

N: First, with a plot of land as small as that 740 sq. meters, there was no alternative but to stack the galleries on top of each other. But when you put galleries on top of each other, you end up with a high-rise building, right? In that situation the most cost-effective method is to make what’s known as a “typical floor plan.” In other words, all the floors end up the same and, as a consequence, the building ends up looking more like an office tower than a museum. So we decided that each floor needed to look different from the others, and to achieve that we needed to vary their sizes.

The other thing was that by changing the size and shifting the positions of each floor, or each gallery (because there is essentially just one gallery per floor), it was possible to add skylights in the middle floors. Normally you can’t have skylights in the middle floors of a high-rise, right, because there’s a room the same dimensions above.

S: The different-sized floors also made terraces on the middle floors possible, and they were important too. In galleries it’s difficult to make windows, because you need walls for the art. So we came up with the skylight and terrace idea. Maybe you could put art on the outside terraces, or something. And people can go out there too, and then you can see the New York skyline from an unusual height.

Museum of Contemporary Art interior. Christian Richters photo

You know, if it’s an office building then the general public doesn’t have free access, but they do in an art museum. So they can come in and enjoy a new dialogue with the city. Also, the building needed to be set back from the street, so each floor is a little smaller than the one below. And we’ve added further variety by changing the ceiling heights of each floor, so a smaller gallery might have a higher ceiling.

The exterior surface of the building is also unusual. What material did you use?

N: It’s a polished aluminum mesh, and it is positioned slightly away from the surface of the building, meaning it is like a double-layered wall. Consequently the wall appears to have a depth to it. Its appearance also changes depending on the weather. When it’s cloudy it looks gray and flat, but when the sun shines the aluminum reflects the sun, and the shadows of the mesh are visible on the internal wall.

S: The other factor was the surrounding neighborhood, the Bowery, which is home to restaurant-equipment suppliers. The mesh was a kind of reference to that, but we’ve made the gauge of the mesh much larger than it would be in any product.

So you tried to relate the building to its surrounding environment?

S: You always need to think about how a building will look beside its neighbors. Of course, that doesn’t mean you should merely imitate them. Neither does it mean you should make the other buildings look bad. The ideal is to create something that, through its presence, makes the overall environment look better, and at the same time makes your own building look good by virtue of its relationship with the surrounding buildings.

Did the New Museum curators have any particular requests?

S: One thing was that they wanted it to be very open to the city, and the public. Of course the galleries are very important, but we’ve also given a lot of attention to the theater, the bookshop, the admission-free zone on the ground floor and even the loading dock, which is right next to the main entrance. There are lots of ways people can interact with the museum.

What impression would you like visitors to have of the architecture when they leave?

S: With a lot of buildings you have no idea, from the outside, how the inside looks. We wanted to make the exterior a more accurate representation of the interior. I’d like visitors to be able to look back at the building and say, “Oh, yeah, I went up there” — and, maybe, “In that room there was this or that piece of art.” I think this design will naturally help them understand the building itself.

Changing the subject, when did you first decide to be architects?

S: When I was in primary school my mother had a magazine with a photo of the Sky House, by (Japanese architect) Kikutake Kiyonori. My parents were about to build a house, so they just happened to have that magazine, and I saw it by accident. I really became interested — interested in the fact that a house could look like that. [Built in 1958 in Tokyo’s Bunkyo Ward, the design consisted of a single volume, elevated on four pylons.] Seeing that photo left a deep impression on me. But I was really small, and they ended up not building their own house, so that spark of interest was quickly forgotten. Then in Japan when you get to the third and last year of high school at about age 16 or 17, you have to decide on a university course. I remembered about that house that had impressed me so much, and so I applied for architecture. At that point I didn’t realize the house was famous, but when I went to university and was in the library I realized that it was.

Toledo Museum of Art’s Glass Pavilion. Arcspa photo

Did you consider anything else?

S: When I was in junior high school I liked fashion, so I was a fan of fashion designers, but I didn’t really have any idea how I could do that. We’re talking about 30 years ago and I was out in the sticks in Sendai, so the idea of becoming a designer was really foreign to me. At least “kenchiku” (architecture) wasn’t a foreign loan word (like “design,” or dezain, as it is pronounced in Japanese). Kenchiku sounded more like the sort of thing you studied at school and then took on as a profession.

Much is made here of the fact that Japanese universities generally include architecture in engineering faculties, whereas in the West it is closer to art.

S: Yeah, that’s right, it’s a branch of engineering. But these days everyone, young people too, have better access to information. At that time, you couldn’t really consider design to be a profession. At the time it was more about, well, I’m not into medicine, not into law, and then I see architecture in the faculty of engineering and it seems like it might be OK to try.

I believe your father was an engineer.

S: Yes, but he is an engineer engineer, not an architect.

Were you influenced by him?

S: No, not really.

N: There was never any particular point when I decided to be an architect. I’m an archetypal Japanese in that way: one day I looked at myself and I was an architect.

S: But you applied to study architecture, right?

N: Yeah, but I only did that because my high-school teacher was like, “You like music and film, and you’re good at mathematics. OK, you’re going into architecture.” I wasn’t really interested in it at all, but I was like most Japanese people and just went along with what I was told. I was set on the tracks and before I knew it I was an architect.

Why did you go to Sejima’s office?

N: It looked interesting. I sensed a real future in her work. When I was doing postgraduate studies at university, I was working part time with Sejima-san and, you know, that hasn’t changed since then. It was fun. They were fulfilling days. I don’t even remember graduating — it was just a continual progression.

Who are your architectural heroes? You have worked together for a long time, so I wonder how well you know each other by now. Nishizawa, do you know who Sejima’s favorite architect is?

N: Mies van der Rohe. (A German-born American architect [1886-1969] known, along with Frenchman Le Corbusier [1887-1965] and German Walter Gropius [1883-1969], as one of the founders of Modern architecture and its pared-back, function-over-form aesthetic that unseated the decorative architecture of the 19th century.)

What does she like about him?

N: Mies, um, I can’t express it. It’s like, “Bam!”

S: “Bam!?”

N: There’s a real stateliness, and sharpness. It’s got originality, with a splendor, or a gorgeousness — no, a splendor. Mies is cool. Yeah, cool. That’s what she likes. And there’s nothing showy about it, nothing unnecessary.

Who does Nishizawa like?

S: Hmm, Le Corbusier! I think he likes lots of things about him. What he often says is that Le Corbusier had his own way of living, and his own ideal, and they coincided. I think he says he likes that. Choosing just one person is always difficult.

N: Yeah, like I’ve never once thought that Le Corbusier was above Mies!

Architecture students have a habit of going on pilgrimages to see famous buildings when they are studying. Where did each of you go?

S: Ah, with me that was . . .

N: A package tour!

S: No, I didn’t actually go on one of those trips.

N: Sejima-san doesn’t do that kind of commoners’ stuff!

S: No! No! But OK, when I was in second year at university I went to Kyushu and saw Isozaki Arata ‘s office/gallery facility, the Shukosha Building, by myself. And then in my third year, my parents said I should see some things outside of Japan, so I applied for this package tour — and the title of the tour was “Looking at Architecture” or something like that. But it was more like a study and recreation trip for construction company employees. I was a student with no money, but everyone else was better off, and they went off here and there on optional tours.

Did you see modern architecture?

S: Well, I thought we would when I applied, but it was more a tour of Middle Ages villages.

N: No modern architecture?! You mean you saw Assisi and places like that?

S: Yeah, and we went to [the World Heritage-listed medieval walled hill town of] San Gimignano in Tuscany, and then to Scandinavia, where we did see (some buildings by Finnish Modern architect) Alvar Aalto. Then we went back to Paris, and they all went off on their optional tours, and I went by myself to see some of Le Corbusier’s buildings.

N: I went to all sorts of places, but I think the first I can remember was with my brother — he is an architect too — and I was in second year. In the middle of summer he issued a directive: “We’re going to look at architecture!” So we walked around Tokyo: Ando Tadao, Maki Fumihiko, Azuma Takamitsu — buildings by all the famous architects. And I think I got sunstroke. You know, I saw lots of architecture, but I still didn’t really get it. Only Ando’s architecture was kind of, like, well this is different from the others. But, you know, it was all architecture. I mean, Tokyo is full of architecture, and when you’re told something is good, you don’t just instantly get it, right? I didn’t know anything. But then after that, when I got a bit older, I decided to go to look at architecture myself in Europe — Paris, Florence, Rome and Greece.

Encased by a glass, full-perimeter wall, SANAA’s 21st Century Museum of Contemporary Art, Kanazawa has no “front” or “back,” so creating an impression of openness and accessibility

Which buildings left the most lasting impressions?

N: First, Paris surprised me with its elegance. I remember I was dropped off by the river near Notre Dame Cathedral. It was night, but it was lit up. I took one look at that glowing scenery and it was like, wow, this is an amazing place. So I found a hotel, and I was so excited that I got up early the next morning. The dawn was more beautiful than any image of Paris I had ever seen in the movies. The other place I remember vividly was St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome. There were lots of memorable things. And the Basilica di Santa Maria Novella in front of the train station in Florence, too.

What about architecture in Tokyo? Which buildings in Tokyo do you recommend to foreign visitors?

N: Maybe Kenzo Tange’s National Gymnasium at Yoyogi (built for the 1964 Olympics) or Kiyonori Kikutake’s Sky House — it’s a great example of Modern Japanese architecture, but it’s a private house, so you can’t really just go and look at it.

Kenzo Tange’s National Gymnasium

S: In a more contemporary vein, maybe Herzog and de Meuron’s Prada Building in Aoyama (which is made of glass). You know, they actually had the nerve to come up with that! Or the Yokohama International Passenger Terminal by Foreign Office Architects. That’s very interesting.

The architecture world has an image of being dominated by men — especially egoistic men who seem to love leaving their mark on the world with big buildings. Do you experience any difficulties or advantages because you’re a woman?

S: Women love making big things too! And small things. With large buildings there are so many people who get involved — and so many people who use the buildings. On the other hand I make small things too; I like designing objects, such as spoons and private residences, which is a very personal process. There is an image that it is only men who make big projects, but I think that’s just because there weren’t many women in architecture in the past. Now that is really changing. There are more women architects now — but people often say that women have a softer image, a softer exterior. We make things through discussion.

So, rather than saying it’s difficult to be a woman, I think maybe there is just a difference of nuance in how we make something. And yes, it is a male-dominated society, and there are good and bad things there. Because I’m a woman, maybe where a man might start yelling I would not yell, and instead say calmly, “I can’t have you doing that.” On the other hand, because there aren’t many women, then sometimes men go easy on us a bit.

How have New Yorkers reacted to the New Museum?

S: Of course, if you asked 100 people and they all said they loved it, then it would be too weird. We’ll be happy if more than half of the people like it. Last week Nishizawa went to see the completion of the building, and a lot of people were stopping to take photos. That was nice to hear.

N: New York, compared with the rest of America, is a really special place. I find it a really special city. Things are always changing in New York. It’s a town constantly in the present-continuous tense. You go there and you can feel the world changing. And of course the New Museum is, you know, new. So for us the idea of the New Museum was the same as the city itself. When you look at New York, most of it was built in the 19th century. We wanted to make a really new, 21st-century building — appropriate for a museum in a city that is always in the business of defining what is new.

Edan Corkill is a staff writer for the Japan Times.

This interview was published in The Japan Times on January 6, 2008 and in Japan Focus on January 6, 2008.