Donald M. Seekins

Summary

This report provides background information and analysis concerning the humanitarian crisis caused by Cyclone Nargis when it passed through the densely populated Irrawaddy Delta and Burma’s largest city Rangoon (Yangon) on May 2-3, 2008. One of the largest natural disasters in recent history, it caused the death of as many as 130,000 people (the official figure on May 16 was 78,000) and resulted in between one and two million people losing their homes and property.

Fatalities are likely to rise both because of the extremely unsanitary conditions in the disaster area, and the slowness of the State Peace and Development Council (SPDC), the Burmese military government, in getting assistance where it is most needed.

In the days following the storm, the SPDC placed major obstacles in the way of the rapid distribution of relief goods and services by the United Nations, foreign governments, international non-governmental organizations and local volunteer groups – a situation that has continued despite warnings from aid experts that a second, man-made disaster – the systematic neglect of people gravely weakened by thirst, hunger and disease and many more fatalities – is on the verge of occurring.

On May 10, the SPDC carried out a referendum on a new military-sponsored constitution, though the vote was postponed to May 24 in the townships most affected by the cyclone. Observers wondered why the referendum was considered so important by the SPDC, given the scale of the natural disaster and the need to commit resources immediately to its alleviation. Resources inside the country that could have been used for relief in the Irrawaddy Delta and Rangoon were in fact used to make sure that the referendum was carried out smoothly.

The military junta was originally willing to accept medicine, food, temporary shelters and other relief goods from foreign parties, but did not wish to have foreign aid workers inside the country distributing these goods or performing other services such as medical care and public health education. This is because the generals fear that a large number of foreigners would be politically destabilizing and they would be able to report to the outside world on conditions inside the country. As a result, the very small number of foreign journalists in the country (the authorities have been attempting to locate and deport them) and Burmese witnesses say that the government’s relief efforts have been grossly inadequate, given the scale of the catastrophe. Observers generally agree that only about a quarter of the worst affected population in the disaster area has received aid. As of this writing (May 26, 2008), it is unclear whether Senior General Than Shwe’s promise to United Nations Secretary General Ban Ki Moon on May 23 that “all” aid supplies and aid experts from foreign civilian sources would be accepted represents a genuine change of heart or is merely a tactic to hold the international community at bay while the military regime seeks to reassert full control over the Irrawaddy Delta.

The humanitarian disaster caused by Cyclone Nargis is likely to have widespread social, economic and political implications for a country where the military regime’s concern for human security as well as human rights has always been minimal. Although the SPDC has expanded armed forces manpower more than 200 percent since 1988 and has allocated a large part of its budget to purchase weapons from abroad and build a new capital, Naypyidaw, 335 kilometers north of Rangoon, it has invested little in health or social welfare. Indeed, many observers claim that social and educational services were actually better under the pre-1988 socialist regime of General Ne Win than under the post-socialist military regime. As a result, Burma is one of the poorest countries in Southeast Asia, outranked in terms of human security and social welfare even by such (former) “basket cases” as Cambodia and East Timor.

Despite heavy repression, popular unrest has periodically flared up, most recently in September 2007 when Buddhist monks and ordinary citizens demonstrated en masse in Rangoon and other towns over steep price hikes for fuel and the SPDC’s brutal treatment of protesters, especially Buddhist monks. The “Saffron Revolution” (so called because of the color of Buddhist monks’ robes) was the largest popular movement in Burma since the pro-democracy demonstrations of 1988. [1]

This report is based on information gathered from the international media (the British Broadcasting Corporation, CNN, MSNBC, New York Times/International Herald Tribune), Wikipedia, the on-line encyclopedia, and Burmese exile news sources (especially The Irrawaddy, published in Thailand) and other sources, as cited in the footnotes.

The following topics are discussed:

I. The Cyclone

II. The Areas Affected

III. Extent of Loss of Life and Property Damage

IV. International Response, SPDC Reaction, Popular Disgust

V. The Rice Crisis: Hunger and Politics

VI. Conclusion: Prospects for Post-Cyclone Burma

I. The Cyclone

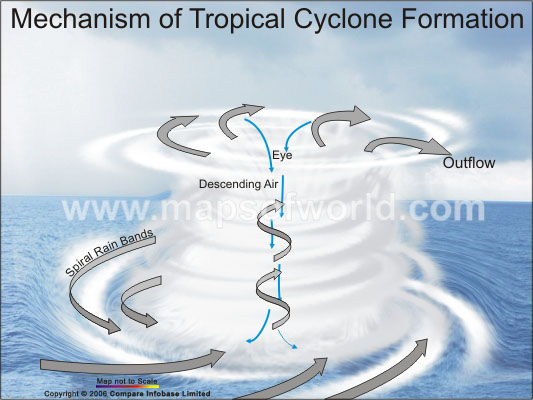

Tropical cyclones are powerful low pressure systems that form in the low latitude regions of the Indian Ocean; similar phenomena are known as typhoons in the western Pacific and hurricanes in the eastern Pacific and Atlantic Oceans.

Mechanism of the tropical cyclone

Mechanism of the tropical cyclone

The cyclone season in the northern Indian Ocean begins in April, but Nargis (as the storm was officially named) differed from most other tropical cyclones in the region by tracking eastward (toward southern or Lower Burma) rather than north or northeast (toward India, Bangladesh, or Burma‘s western state of Arakan). [2] It emerged in the middle of the Bay of Bengal on April 27, making landfall in the evening of May 2 with sustained winds of 121 mph (192 kmh) south/southwest of the town of Labutta (Laputta) in Irrawaddy Division. From there it moved in a northeasterly direction through Bogalay and Pyapon, veering just north of Burma’s old capital of Rangoon before moving into the hilly Burma-Thai border area and dissipating. Peak winds reached a speed of 135 mph (215 kph), but the force of the storm diminished as it passed over land (sustained winds of 81 mph-128 kmh in the vicinity of Rangoon). [3]

II. The Areas Affected

Over the centuries, the Irrawaddy Delta has been formed by alluvial soils brought from the northern part of the country by the Irrawaddy River, Burma’s longest, which has its headwaters in northern Kachin State. The river-borne soil has gradually changed the shape of Burma’s coastline, enlarging it in a southwestward direction. The city of Rangoon straddles the low-lying alluvial region of the Delta and higher ground that is associated geologically with the Pegu Yoma, a range of hills that divides the Irrawaddy River Valley from the Sittang River Valley to the east. To the south and southwest of Rangoon, the land is flat and very low in elevation, crisscrossed by hundreds of small creeks and as well as the major channels of the Irrawaddy River that empty into the Andaman Sea.

British writer and former colonial official Maurice Collis described the Delta in his 1953 book, Into Hidden Burma:

Myaungmya district lay among the tidal creeks of the Irrawaddy Delta, a vast rice plain of the utmost fertility but without natural features to relieve its monotony. Before the British entry into Lower Burma in 1825, the whole delta had been largely an uninhabited swamp. Seen to be very suited for the growing of rice, its cultivation had been gradually effected with the help of imported Indian labour. By 1920, it was yielding an enormous crop, a great part of which was bought by Rangoon merchants, British and Indian, and exported on British ships. [4]

Transportation within the Delta and to areas outside it has traditionally been by boat rather than road or rail, though there is a rail link between the Delta’s largest city Bassein (which seems to have escaped the worst storm damage) and Rangoon. Most human habitations are located close to the sea, or near creeks, ponds and other bodies of water inland: the most common form of housing is made of bamboo and thatch, rather than more permanent materials such as wood, concrete or bricks. Human settlement is dense by Burmese standards (470 people/square mile in Irrawaddy Division, well above the national average), but rural in nature. [5] As Collis mentioned, this was (and remains today) Burma’s rice bowl. Before World War II, Burma was the world’s largest exporter of rice, most of it coming from the Delta. Although the country’s rice exports have declined since 1941, the Delta still produces 65 percent of Burma’s total crop. [6] Though not now a major exporter, Burma is the world’s sixth largest producer of rice and damage to croplands by the cyclone will require large-scale emergency imports of rice from neighboring countries such as Thailand and Vietnam that are already strapped by shortages of the staple grain. [7] Fishing and aquaculture are also economically important, and the region is the major producer of ngapi (fermented fish paste), a Burmese diet staple.

Collis noted the ferocity of the Delta’s mosquitoes: “. . .wire netting of small mesh. . .was a protection against mosquitoes, which during the monsoon were so troublesome in the creeks that, unless shut in a room like a meat safe, you could not sit and read after dark.” [8] Following the cyclone, mosquito-borne diseases such as malaria and dengue fever are among the biggest threats to public health in the area.

Although accurate statistics on the ethnic composition of the Delta population are unavailable, they include Burman, Karen, Arakanese, Chin, Chinese and Indian communities. [9] Many and perhaps a majority of the people are Karens. Karen National Union insurgents have operated in the area as recently as 1991, making Delta Karens targets for government retaliation. [10] It is unclear whether the large Karen community and the history of Karen insurgency in the delta partially explains the SPDC’s indifference to the cyclone victims’ plight – the junta has generally displayed little interest in the human security of the population, no matter where they live or what ethnic group they belong to. [11]

III. Extent of Loss of Life and Property Damage

On May 16, 2008, the SPDC released official figures of 77,738 fatalities and 55,917 missing (figures on May 12 were 28,458 deaths and 33,416 missing), but United Nations and foreign embassy officials have said that as many as 130,000 may have died, a figure still cited by United Nations and other observers in late May. [12] They have also warned that unless aid measures are speeded up, as many as 1.5-2.5 million people are at dire risk from disease, dehydration and starvation. [13] Probably the exact number of victims will never be known. As a comparison, an estimated 300,000 people died in the Bhola cyclone that hit Bangladesh in 1970; the December 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake caused around 240,000 deaths in a number of countries (principally Indonesia), and a 1991 cyclone in Bangladesh killed around 140,000 people. [14]

In all of these cases, most of the victims died as a result of a powerful tsunami or “storm surge.” [15] When Nargis hit Burma, a three to four meter-high wall of sea water was driven up onto the low-lying land by the storm and inundated as much as 2,000 square miles (5,180 square kilometers) of the coastal area, drowning tens of thousands of local residents. Satellite images of the Delta published in the media reveal that several days after the storm large areas remained submerged under saline water. Whole villages disappeared, their houses completely destroyed, most boats were damaged beyond repair and most of the rice crop both in the fields and in storage was ruined.

Death rates were higher in the western and central parts of the Delta than in Rangoon, with an especially large number of casualties in the towns of Labutta, Bogalay and Pyapon. Although the storm passed close to Rangoon, a city of between five and six million people, fatalities were reportedly fewer because of the absence of a storm surge (Rangoon is located about 20 miles/32 kilometers inland), the more solid structure of many of the city buildings (though there was widespread damage, including metal roofs being blown off houses) and the fact that the winds had diminished in intensity by the time they reached Burma’s old capital in the early morning of May 3. [16] However, satellite towns outside of Rangoon were heavily damaged due to the prevalence of thatch and bamboo structures. These are the areas where the city’s poorest people live, most of them former central city residents forcibly relocated outside of town by the State Law and Order Restoration Council (as the SPDC was known before 1997) after it seized power in September 1988. Many of them are so poor they cannot afford to buy rice, and get nourishment from drinking the water that rice has been boiled in.

Thanks to the international airport at Mingaladon, delivery of aid is relatively unproblematic (in a logistic sense) in the Rangoon area, but the Delta provides serious challenges to providing relief because of the lack of good roads and the inundation caused by the storm surge, which has cut off many cyclone survivors from the outside world. Their shelter has been almost entirely destroyed. Aid specialists described a “race against time” to bring food, medical supplies and temporary shelter to these people, especially children, who are vulnerable to measles, dengue fever, malaria, digestive disorders and other illnesses. [17] In the days following the cyclone, the greatest need has been for clean water: even in Rangoon, observers described water being sold to residents that had been obtained from Inya Lake, a scenic but polluted body of water north of the city’s downtown area. In Delta areas, desperately thirsty people have gotten water from ditches or streams where the bodies of drowned humans and animal carcasses remain, unburied.

A major factor in high death rates in the Delta seems to have been the depletion of mangrove forests in the tidal areas along the coast, which act as a natural shield to stop or at least moderate storm surges moving inland. Following the 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, experts discovered that areas protected by mangrove forests suffered far less devastation than those where the forests had been cut down. Like other tidal areas of South and Southeast Asia, the Irrawaddy Delta has lost mangrove forests due to the clearing of new rice fields and the establishment of fish and shrimp farms. [18] Seafood (especially shrimps) grown on such farms is one of Burma’s major exports and foreign exchange earners.

IV. International Response, SPDC Reaction, Popular Disgust

Once information about Cyclone Nargis’ devastation reached the outside world, plans were made for an effective international response. Donors could draw on the recent experience of the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami to deal with a situation that was similar in many if not most respects. The United Nations called for US$187 million in funds for Burma relief. The French, British and US navies had ships located near the storm-stuck Delta from which aid materials could be brought quickly by helicopter.

On the ground, people were mystified by the SPDC government’s passive response to the disaster. Few troops or members of the Union Solidarity and Development Association (USDA), a pro-government “grass roots” organization, were evident on the streets of Rangoon or in the Delta; local residents and Buddhist monks were doing most of the recovery work, including removal of fallen trees and utility poles and the provision of temporary shelters. One group especially prominent in relief efforts both in Rangoon and the Delta has been the Free Funeral Service Society, a civil society group organized in recent years by Kyaw Thu, a well known actor and dissident, to provide decent burial for people whose survivors are too poor to afford it. [19]

One woman in Rangoon complained: “where are all those uniformed people who are always ready to beat monks and civilians? They should come out in full force and help clean up the area and restore electricity.” [20] She was referring to the “Saffron Revolution” protests of September 2007, when troops, riot police and paramilitary groups were quickly and efficiently mustered to crush dissent, causing (according to opposition sources) as many as two hundred deaths. Similar expressions of frustration were heard throughout the disaster area in the days that followed. On May 11, Japanese broadcast network NHK televised a feature in which a Burmese doctor interviewed in a makeshift clinic stated that no relief measures had been taken by the authorities, and injured or sick people had received absolutely no assistance. [21] According to the INGO Medecins sans Frontieres, “More than one week after the disaster, despite the sending of three cargo planes and some positive signals, it has been very difficult to provide highly needed supplies for the heavily affected population in Myanmar. . .In the areas we have been we haven’t seen any aid being delivered so far, so the amount that has reached people in the areas where we are has been minimal.” [22]

Although the SPDC affirmed that it was ready to receive foreign assistance, it became evident in the days following the cyclone that while it was willing to accept supplies, it did not want a large number of foreign experts inside the country, including persons monitoring the distribution of relief goods or involved in long-term post-disaster development projects. Only a trickle of aid came in, mostly by air to Rangoon’s Mingaladon airport. Some of it was confiscated and placed in storage by the authorities, but later released. Aid workers were subjected to long visa application processes at the embassy in Bangkok and elsewhere, planes waited at airports in neighboring countries for permission to deliver their supplies and relief personnel already in the country were given little or no assistance by the government in getting to the worst hit areas, where, as mentioned, as many as 2.5 million people were at risk a week after the storm. [23]

The junta’s initial slow reaction to the disaster is perhaps understandable: Burmese army and police have been trained exclusively in imposing internal order, not disaster relief. Moreover, there has been no catastrophe like Cyclone Nargis in living memory in Burma (in contrast to Bangladesh, where major cyclones have frequently caused huge losses of life). But in the aftermath of the cyclone, the SPDC’s behavior has seemed at times unbelievably callous. The May 10 referendum on the new constitution went ahead as planned, except in areas worst hit by the cyclone where the voting was held on May 24; the state media devoted more attention to the vote than to the natural disaster, including a telecast in which young ladies sung cheerful songs urging the people to cast their ballots “with sincerity” for the sake of the nation. SPDC Chairman Senior General Than Shwe, who kept an extremely low profile in his new capital of Naypyidaw in the days immediately following the disaster, was shown on state television casting his “yes” vote on May 10 for the new basic law along with his wife Daw Khaing Khaing.

Moreover, the Los Angeles Times reported on May 10 that while little food or fresh water was reaching the cyclone victims, rice was being exported from the Thilawa container port south of Rangoon to Bangladesh, apparently in an effort to generate foreign exchange while world rice prices are high. Such rice exports are not the responsibility of the private sector, but of a state corporation under the direct control of the military. People interviewed in the area said that they had received small amounts of “rotting” rice from the government, while officials kept supplies of instant noodles for themselves. [24] On May 11, the International Herald Tribune reported that Burmese rice was also being shipped from Rangoon to Malaysia and Singapore. [25]

By late May, spurred by the urgings of UN Secretary General Ban, who met with SPDC top general Than Shwe on May 23, a larger volume of aid has flowed in and the government has promised to allow foreign aid experts to work without restrictions in the affected areas. Yet the SPDC’s overall response to the disaster seems to be motivated by the principle that “politics is in command” – to borrow Mao Zedong’s well-known phrase. This is true in three ways. First, the military regime has made the country’s unity, independence and self-reliance a central theme in its propaganda, as reflected in the “Three Main National Causes” adopted after the SLORC takeover in September 1988: “non-disintegration of the Union,” “non-disintegration of national solidarity” and “perpetuation of national sovereignty”; and in another group of slogans, “People’s Desire,” which include “oppose those relying on external elements, acting as stooges, holding negative views” and “crush all internal and external destructive elements as the common enemy.” [26] For a regime so proud of its self-sufficiency to admit that it is helpless in the face of the cyclone disaster would be – for Than Shwe and his fellow generals – a terrible loss of face, even though the alternative – many more deaths and ever greater popular hatred of the SPDC – would undermine their legitimacy in the longer run.

Secondly, apart from considerations of face and prestige, the arrival of hundreds if not thousands of foreign relief workers in the Delta and Rangoon would have great potential for destabilizing an already tense political situation, especially in light of the large anti-government protests of September 2007. It would show ordinary people more vividly than ever how poor and undeveloped Burma has become under military rule, in comparison not only with western countries but Burma’s Asian neighbors (for example, Indonesia has promised substantial aid). Space might be opened up in which people could organize themselves more effectively against the regime with tacit if not open international approval. In the generals’ eyes, a foreign presence in the disaster area on the scale of the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake seems to be more unthinkable than accepting death tolls far higher than the May 16 official figure of around 78,000 or even the UN estimate of 130,000.

Thirdly, the SPDC can use aid donated by the United Nations and foreign countries to deepen the chasm between “Us” (the military and civilian supporters of the regime, such as the USDA) and “Them” (practically everyone else) in Burmese society. By using political rather than needs-based criteria to divert relief supplies to its supporters, the junta hopes it can solidify its grip on power even while the population at large regards it with increasing hatred and contempt.

This reflects a highly ironic development: SPDC apologists routinely accuse the old British colonial regime of dividing the Burmese people against themselves (especially ethnic minorities such as the Karens who served in the colonial army and police against the ethnic majority Burmans) while setting themselves up as an elite caste who became rich from the sale of the country’s natural resources. However, in the evolving political system that will be more firmly established with the almost unanimous (and highly manipulated) approval of a new constitution on May 10th and 24th, the Burman-dominated army has isolated itself not only from frontier area ethnic minorities such as the Karens, Shans and Kachins, but also from the largely Burman population in the central part of the country. While ordinary soldiers are often very poor, higher ranks enjoy their own schools and colleges, hospitals and clinics, stores, golf courses, comfortable living spaces and above all business connections that allow them to enjoy a standard of living far superior to that of civilians. Most military personnel live in self-contained cantonments not unlike those of the British colonial era.

To preserve its power base in an environment of growing scarcity (following the cyclone), the SPDC has to provide the 400,000 members of the armed forces and their families (a total of about two million people) and pro-regime groups such as the USDA, which was established in the early 1990s by Senior General Than Shwe, and the Swan Arr Shin (“Masters of Force”), a paramilitary group of more recent origin, with basic necessities, even while making little or no effort to make them available to the general population. [27] This may explain reports that food obtained from abroad such as high energy biscuits is being placed in army storehouses while the people are being given poor quality rice and other inferior foodstuffs. [28]

The USDA and Swan Arr Shin (“Masters of Force” in Burmese) have played an increasingly important role in suppressing civilian dissent, not only during the September 2007 “Saffron Revolution” but in the “Black Friday” incident of May 30, 2003, when toughs associated with the USDA attacked Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and her supporters in Sagaing Division in Upper Burma, killing as many as 70 or 80 people. [29] There is speculation that the USDA might be transformed under the new constitution into a “mass” political party – not unlike the Ne Win-era Burma Socialist Programme Party or Golkar in Soeharto-era Indonesia – that would function as the military regime’s main pillar of “popular” support in the new constitutional order.

In late 2005, Than Shwe ordered the removal of the nation’s capital from crowded and unrest-plagued Rangoon to a new city, Naypyidaw, in the central part of the country. The new capital site is relatively isolated and thinly populated, an ideal location from which to control Burma’s population in a largely coercive manner, a further decisive step in the isolation of the military elite from the society as a whole. Observers commented cynically that Senior General Than Shwe had been warned by his personal astrologer to move the capital, lest he and his fellow generals be overthrown; but the major factor in the capital relocation seems to have been the desire of the junta to insulate itself from popular unrest in Rangoon and other major cities.

V. The Rice Crisis: Hunger and Political Unrest

The connection between shortages of rice and political unrest is ne of the constants of Burmese and Southeast Asian history. During the 1920s and 1930s, when the country was under British colonial rule, the Burmese population suffered a decline in living standards, especially a decline in the consumption of rice, due to falling rural incomes, growing farmer indebtedness and the foreclosure of Burmese-owned farms (especially those in the Irrawaddy Delta), which often passed into the hands of Indian moneylenders. Former landowners became tenants, agricultural workers or part of a floating population that migrated to Rangoon and other towns in search of low-paid work, often competing with immigrant Indian workers for scarce jobs on the docks or in the rice mills. At the same time, rice exports remained at high levels, generating profits for British and other foreign companies. [30]

Colonial Burma witnessed numerous armed revolts against British rule of which the most prominent was the Saya San uprising of 1930, a rural insurgency that sought unsuccessfully to eject the colonialists and restore the old Burman dynastic order. Many of the most active young nationalists at this time came from the Irrawaddy Delta, such as Thakin Nu (later U Nu, independent Burma’s first prime minister), a native of Wakema, a town located on the path of the 2008 cyclone.

Flawed socialist economic planning and an inefficient and corrupt distribution system created rice shortages and inflation during the years when General Ne Win’s military regime was in power (1962-1988), and these in turn led to large-scale popular unrest: the anti-Chinese riots of May 1967, the labor strikes of May and June 1974 and especially the protests of 1988. In August 2007, the SPDC announced increases in fuel prices of as much as 500 percent, which had a major impact on food as well as transportation costs. The following month, the “Saffron Revolution” led by Buddhist monks constituted, as mentioned, the largest example of popular resistance against the state since 1988.

Given the severe damage inflicted by Cyclone Nargis on rice growing areas in the Irrawaddy Delta and the need to import rice from other countries (such as Thailand and Vietnam) that now have problems feeding their own people, rice shortages are most likely to be a fact of life in Burma for several years to come. These shortages will translate into chronic instability, made worse by the widespread (and apparently true) reports that the military regime is setting aside a large amount of the rice and other staples available (including foreign donated food) to feed the army and its civilian supporters (such as the USDA) rather than the general population. As in North Korea, which has been afflicted with natural disasters and famines in which hundreds of thousands of people have died, the international community is likely to face a vexing problem: although it would be morally unacceptable to deny food aid to Burma in coming years, the suspicion that such aid only helps the regime stay in power will undermine the will to provide relief.

VI. Conclusion: the Prospects for Post-Cyclone Burma

As in many parts of the world, people in Burma believe that natural disasters portend the fall of dynasties, a sign that the country’s rulers are losing their grip on power. Given the importance of Theravada Buddhism in Burmese culture for over a thousand years, the most baleful portents have involved storm or earthquake damage to Buddhist pagodas. In the early sixteenth century, a strong wind (a cyclone?) blew the hti (“umbrella”) or jewel-encrusted finial off the top of the Shwedagon Pagoda in Rangoon and left it at some distance from the pagoda hill. The Shwedagon is the most revered site in Burmese Buddhism, believed to contain the relics of not one but four Buddhas, and the dissolute king took the pagoda’s storm damage as a sign that he should repent of his many evil deeds. However, he died the next year. [31] In 1930, a large earthquake leveled the Shwemawdaw Pagoda in Pegu, northeast of Rangoon, causing hundreds of deaths. The calamity was followed by bloody communal riots between Burmese and Indians in Rangoon and the village-based rebellion of Saya San, which the British suppressed with considerable difficulty.

When the SPDC began an ambitious project to renovate the Shwedagon in 1999, replacing its old iron finial with a new stainless steel one, many people believed that they would fail, because they were morally unfit to carried out such religiously important work (only “true kings” could adorn major pagodas like the Shwedagon). Small earthquakes apparently occurred, but under the generals’ sponsorship the project was completed successfully in April 1999. [32] To ordinary Burmese, this was deeply discouraging, since it seemed to show that the SPDC had sufficient merit (kutho in Burmese, the karmic sum of good actions [karma in Sanskrit or kamma in Pali] performed in previous lives) not only to perform further Buddhist good works but also to stay in power indefinitely. [33] In the 2008 cyclone, the Shwedagon has reportedly been damaged, although there are no reports that the hti again has fallen from the Shwedagon’s summit. [34]

Is Cyclone Nargis a portent of regime change? Some observers argue the opposite. As mentioned above, Than Shwe’s personal astrologer is said to have advised him to move his seat of power, lest his regime be overthrown. With the relocation of the capital to Naypyidaw in the central part of the country, the Senior General has escaped the cyclone’s devastation. It has been suggested that his good fortune is due to his still abundant store of merit (also reflected in the successful Shwedagon renovation project). Had the SPDC remained headquartered in the old capital, its power structure would have been severely, perhaps irreparably, damaged. A former British ambassador to Burma has gone so far to claim that “. . .his [Than Shwe’s] karma has been saved and it is the people who have suffered, not the generals.” [35]

The natural and human disaster in Burma is now at a crucial turning point. Following the intervention of UN Secretary General Ban (his visit to the country on May 22-23, and his return to Rangoon in order to preside over a donors’ conference on May 25), Senior General Than Shwe’s promise to open the disaster area up to a large number of foreign relief workers may constitute a genuine departure from the junta’s previous obsession with total control and self-sufficiency. Over time, sustained relief operations may have the consequence of eroding the SPDC’s xenophobia, contributing to the emergence of a more open and liberalized society and politics. But this is a very optimistic scenario. Given its past behavior, it is more likely that the regime will insist upon continuing restrictions on access to the affected population in the Delta, not only for foreign aid workers but also for Burmese donors, who have faced serious obstacles in getting food, medicine and other supplies to the people who need them.

If this pessimistic scenario is played out, the conjuncture of vast human misery and SPDC misrule means that social and political unrest like the “Saffron Revolution” will continue in Burma over the coming years, a cycle of protest and repression that has marked Burma’s history since at least the establishment of the first military regime by Ne Win in 1962. The people will not be strong enough to overthrow the heavily-armed regime, but if past history is any indication they will not – despite talk of the Senior General’s kamma – passively endure SPDC misrule.

There is a Buddhist saying that there are three errors in understanding kamma: first, denying that kamma, or the sum of merit or demerit from past lives, can have consequences for one’s present life (good and ill fortune happen randomly); secondly, believing that good and ill fortune are the work of a Supreme Being; and thirdly, assuming that all things that happen in this life are due to the working out of kamma, that there is no room for individual responsibility and decision-making since everything has been pre-determined in past lives. [36] In the case of the Than Shwe regime’s unwelcome longevity, the basic problem is not karmic, supernatural, or even natural – but human.

Since the SPDC was established in 1988, the international community has repeatedly failed to forge a coherent and consistent policy to deal with the country’s deepening social, political and economic crises, in large measure because of differing national interests that have been covered with the fig leaf of “respecting national sovereignty.” Neighboring Asian states, particularly China but also India, Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia and others have propped the regime up, acquiring its natural resources, especially natural gas and forest products, in exchange for giving the SPDC economic, military and ideological backing. With the rapid economic development of China, India and some ASEAN states creating intense demand for Burmese raw materials, an increasingly integrated economy is emerging in continental Asia placing raw material-exporting countries like Burma in a position of “colonial” (or neo-colonial) dependence in relation to wealthier, more industrialized states. In this new (but also old) economic division of labor, the SPDC serves the function of delivering needed commodities to its wealthy neighbors while using its home grown army to make sure that the local inhabitants do not cause too much disruption – roles once played by the British Indian Army and military police, as described vividly by George Orwell in his novel Burmese Days.

Western countries, especially the United States, have made Burma an international human rights issue but have imposed poorly planned and ill-targeted sanctions that have harmed ordinary people more than the generals and their capitalist cronies (for example, President George Bush’s 2003 “Burmese Freedom and Democracy Act” which banned Burmese exports to the United States and caused layoffs among workers in textile factories). The United Nations, despite appointing numberless special envoys, has accomplished little in the way of getting the SPDC to improve its behavior toward the democratic opposition or the people in general. The worsening humanitarian disaster initially caused by Cyclone Nargis is primarily the regime’s responsibility; but the international community through its inaction has created an environment in which the junta can act with continued impunity.

If the disaster motivates the United Nations and major nations to successfully come together on Burma and implement a coordinated and effective policy, then one good thing will have come out of Cyclone Nargis. But it will have come at a terrible price.

Donald M. Seekins is Professor of Southeast Asian Studies at Meio University. He is the author of The Disorder in Order: the Army-State In Burma since 1962. E-mail contact: [email protected].

He wrote this article for Japan Focus. Posted on May 26, 2008.

Notes

[1] On that protest, see Human Rights Watch. Crackdown: Repression of the 2007 Popular Protests in Burma. New York: Human Rights Watch, 2007.

[2] Nargis meaning “daffodil” in Urdu, is described as “the world’s fifth largest natural disaster in four decades.” Denis Gray. “Myanmar set for political, economic shocks after greatest natural disaster.” Associated Press, Bangkok (May 11, 2008).

[3] “Cyclone Nargis” in Wikipedia; “Mapping the aftermath of Cyclone Nargis,” The New York Times, May 8, 2008.

[4] Maurice Collis. Into Hidden Burma. London: Faber & Faber, 1953: p. 61.

[5] Hla Tun Aung. Myanmar: the Study of Processes and Patterns. Rangoon: National Centre for Human Resources Development, 2003: p. 610.

[6] Wai Moe. “The Irrawaddy Delta: before the Cyclone.” The Irrawaddy on-line, May 10 2008.

[7] “Burma cyclone raises rice price.” BBC News on-line , May 9, 2008.

[8] Collis, Hidden Burma, p. 64.

[9] Hla Tun Aung, Myanmar, p. 611.

[10] Wai Moe, “The Irrawaddy Delta.”

[11] For example, many Burman residents of Pyinmana in centrally located Mandalay Division were forcibly relocated in order to make way for construction of the SPDC’s new capital of Naypyidaw in 2005.

[12] “Cyclone toll rises to almost 78,000.” Associated Press. MSNBC.Com, May 16, 2008, accessed 05-17-2008. The British government gave an “unofficial estimate” of as many as 217,000 dead or missing.

[13] “Burma eases restrictions on aid.” BBC News, May 11, 2008 .

[14] Amitav Ghosh. “Death Comes Ashore.” The New York Times, May 10, 2008.

[15] Ibid.

[16] “Mapping the Aftermath of Typhoon Nargis,” New York Times, May 8, 2008.

[17] Associated Press. “’Race against time’ to avoid disease disaster.” MSNBC.Com , May 10, 2008.

[18] Michael Casey. “Before cyclone hit, Burmese delta was stripped of defenses.” International Herald Tribune, May 9, 2008.

[19] “Myanmar exports rice as cyclone victims struggle.” Los Angeles Times, May 10, 2008 .

[20] “240 People Dead; Number of Dead, Injured Expected to Climb.” The Irrawaddy on-line, May 4, 2008.

[21] NHK News broadcast, May 11, 2008 (evening).

[22] Aung Hla Tun. “Agencies report aid deliveries to Myanmar ‘minimal.’” Reuters, in the International Herald Tribune, May 12, 2008.

[23] BBC News telecast, May 11, 2008, 22:00.

[24] “Myanmar exports rice as cyclone victims struggle.” Los Angeles Times, May 10, 2008.

[25] “Myanmar junta still blocking cyclone aid.” International Herald Tribune, May 11, 2008, accessed 05-12-2008.

[26] These slogans still appear prominently in government publications and large billboards, often written in both Burmese and English.

[27] Brian McCartan. “Why Myanmar’s junta steals foreign aid.” Asia Times on-line, May 14, 2008.

[28] Los Angeles Times, “Myanmar exports rice as cyclone victims struggle”; Associated Press. “Cyclone victims getting spoiled food.” MSNBC.com –on line, May 13, 2008.

[29] By contrast, the 1988 protests were suppressed by the army (Tatmadaw) and special Riot Police (Lon Htein).

[30] James C. Scott. The Moral Economy of the Peasant: Rebellion and Subsistence in Southeast Asia. New Haven: Yale University, 1976: pp. 87, 88.

[31] B. R. Pearn. A History of Rangoon. Rangoon: American Baptist Mission Press, 1939: p. 26.

[32] Aung Zaw. “Shwedagon and the Generals.” The Irrawaddy magazine, vol. 7: no. 4 (May 1999): pp. 12-14.

[33] Ingrid Jordt. Burma’s Mass Lay Meditation Movement: Buddhism and the Cultural Construction of Power. Athens: Ohio University Press, 2007: pp. 188-189.

[34] “Rangoon struggles to survive.” The Irrawaddy on-line, May 12, 2008, accessed 05-12-2008: “….more than 1,000 precious stones – jade, rubies, emeralds and sapphires – fell off the golden pagoda.

[35] Ed Cropley. “’Bad karma’ behind Myanmar cyclone?” The Japan Times Weekly, May 17, 2008: p. 5.

[36] “Karma in Buddhism.” Wikipedia on-line encyclopedia, accessed 05-18-2008.