Tony McNicol and David McNeill

Two recent libel cases have led to concerns that the freedom of Japanese journalists to investigate and, if necessary criticize the powerful is under attack. Both involve marginal publications that make a living tackling “taboo” subjects and which have suffered serious legal repercussions as a result. The mainstream media in Japan has so far declined to discuss the issues, still less to offer any expressions of solidarity for their plight. The cases coincide with the publication of a report by Reporters Without Borders, which called the “steady erosion” of press freedom in Japan “alarming” and again criticized the stifling role of press clubs on reporting in the world’s second-largest economy.

Imprisoned for libel

Tony McNicol

Publisher’s arrest and imprisonment for libel is ignored by the Japanese media.

Publisher Matsuoka Toshiyasu first realized something was up that July 2005 morning when he opened his Asahi Newspaper: “Kobe prosecutors issue arrest warrant for Rokusaisha publishing house president on suspicion of defamation.” Before long reporters and TV crews had gathered outside his Kobe home and office. At 8 a.m. prosecutors arrived and he barely had time to make a comment to the media before being taken away to Kobe detention center. “This is a violation of the 21st (free speech) clause of the constitution,” he said. “We will fight this.” He wasn’t to be released for another 192 days.

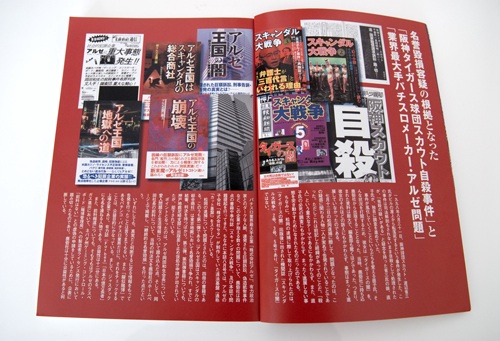

Prosecutors accused the publisher of defaming executives of Aruze Corp., a pachinko gambling machine and slot machine maker, with allegations of tax evasion and unethical business practices. They also accused him of defaming ex-employees of the Hanshin Tigers baseball team through allegations that a former scout for the team was murdered. Prosecutors cited books published by Rokusaisha, information on their website, and their quarterly magazine “Kami no Bakudan (“Paper Bomb”).

Rokusaisha’s flagship magazine had attempted to establish itself as a fearless outlet for the stories other publications wouldn’t touch. Before Matsuoka’s arrest it covered a range of so-called “taboo” topics in Japan, like Johnny’s Jimusho entertainment agency, financial scandals involving the Mitsui Sumitomo bank, and reports on politician Abe Shinzo (now Japan’s Prime Minister). It had, however, paid particular attention to Aruze Corp, with articles and books on the company by Rokusaisha president Matsuoka. The publisher was already being sued by Aruze for libel at the time of his arrest.

“I had been sued before, but I wasn’t expecting to be arrested,” said Matsuoka. He pointed out that criminal arrest for libel was almost unprecedented in Japan, never mind the 192 days he spent in jail before his case came to court. Last July the publisher was issued a suspended sentence of one year and two months imprisonment, which he is now appealing.

While the facts of the arrest were covered by most of Japan’s national newspapers, Japanese journalists – with the exception of local Kobe media – showed little solidarity with Rokusaisha. Even Japan’s leading liberal daily, The Asahi Shimbun, effectively looked the other way. Ironically, an Asahi reporter interviewed Matsuoka the day before he was taken into custody, and reported the arrest before it even happened. Kami no Bakudan editor Nakagawa Motohiro suspects the newspaper used its contacts in the Kobe prosecutor’s office. “The Asahi Shimbun reporters in the police press club knew more about what was happening than we did,” he said.

The Chief Spokesman for Matsuoka’s support group, Hayakawa Yoshiteru, said he made repeated, unsuccessful attempts to stage press conferences: “I contacted the national media, but the journalists who I spoke to said their stories wouldn’t get published.” (When this reporter pitched a story on Matsuoka’s arrest to a Japanese weekly magazine he occasionally writes for, he got a curt reply: “I don’t have any interest in a story on him.”)

Of the weeklies, only the Shukan Asahi weekly magazine offered robust support. In a two-page interview, Okadome Yasunori, the well known ex-editor of defunct scandal magazine Uwasa no Shinso (“the truth behind the rumors”), was unequivocal about the implications of the arrest. “If we casually permit a member of the media to be arrested on suspicion of defamation,” he said, “it is the same as if freedom of speech had died.”

Perhaps Kami no Bakudan, a small circulation magazine in Kansai far from the Tokyo based media, was unlikely ever to garner much support. The magazine had pledged to continue the work of Japan’s most daring scandal magazine Uwasa no Shinso, but it had failed to draw anything like that publication’s readership. At its peak, Uwasa no Shinso’s circulation rivaled other weekly magazines. Kami no Bakudan monthly sales were 25,000 before the arrest, and half that now.

And Kami no Bakudan’s murky image (even for a muckraking weekly magazine) can’t have helped its cause. “Even if it is attacked, Rokusaisha is the kind of company that other media won’t support,” said Yamaoka Shunsuke, an investigative journalist and freelance contributor to the magazine, “It is considered a scandal magazine . . . not a serious magazine.” He added that the publisher hasn’t established the friendly links with other media that Uwasa no Shinso enjoyed. Many of that magazine’s scoops came via journalists in the mainstream media.

“[Uwasa no Shinso] may have been a black sheep, but it was still part of the herd,” agreed Mark Schreiber, co-author of Tabloid Tokyo, a collection of summarized and translated articles from Japan’s weekly magazines. Rokusaisha, on the other hand, is on the fringes of the media in more ways than one, he noted. “This is a Kansai (Western Japan) based publication with national circulation; that’s very rare.”

“I think this is par for the course,” said Schreiber. “In one form or another, these publications are constantly in trouble.” He pointed out that the magazines rely on scandal-seeking reports, often outrageous invasions of privacy, for the bread and butter of their business. To that extent, legal action comes with the territory.

Nor does he believe that magazines like Uwasa no Shinso and Kami no Bakudan are quite the fearless taboo-breakers they make themselves out to be. “Some of [their journalists] take the position that they are crusaders,” said Schreiber. “They make a show of being fearless, but they don’t have the time or the money to go out there and really dig. They are dependent on people dropping stuff in their laps. It is a forum for people who want to spill the beans.”

There were suspicions too that Rokusaisha is embroiled in a factional struggle within the Pachinko industry. Unlike Uwasa no Shinso, who issued a wide-ranging assault on a spectrum of media taboos, Rokusaisha has concentrated on pachinko machine maker Aruze with four books and various magazine articles. Asked flatly at the FCCJ press conference whether Rokusaisha had received money from Sammy, Aruze’s pachinko industry rival, Matsuoka said no. But he also said he was surprised when Sammy pre-ordered 3,000 copies of his first Aruze book’s 13,000 print-run.

Nevertheless, observers say that the police’s highly unusual decision to take Matsuoka into custody has dark implications. Terasawa Yu, a freelance journalist who reports on the Japanese police for weekly magazines pointed out that both Aruze Corp. and the Hanshin Tigers baseball team employ ex police officers in “amakudari” adviser positions. The colossal 30 trillion yen pachinko gambling industry, technically illegal, is kept rolling through legal loopholes and the close cooperation of the Japanese police. Terasawa suggested that the companies may have used their police contacts to engineer Matsuoka’s arrest.

Matsuoka’s imprisonment has been an exceptional case, but Terasawa points out that huge libel demands have already become a tried and tested tactic for companies who wish to silence freelance journalists and small publications. He himself was unsuccessfully sued by loan company Takefuji. “The companies don’t even need or expect to win,” he said. “They just want to intimidate journalists.”

Uwasa no Shinso editor Okadome said that that libel payments have increased greatly in the last few years. Okadome was involved in around 40 libel cases during 25 years at the magazine, but he said payouts have grown 10 fold and that the most famous plaintiffs, notably TV personalities and politicians, get the most money.

Music journalist Ugaya Hiro is the latest freelance journalist to feel the heat. He came to the FCCJ not long before Matsuoka to talk about the ¥50 million law suit he is fighting against Oricon, the company that publishes Japan’s pop-music charts (see related article by David McNeill). Ugaya is being sued over brief comments he made in a telephone interview questioning the accuracy of the charts. He was also at the FCCJ to hear Matsuoka speak and during the Q&A he wryly asked the Rokusaisha editor for advice on defense against gangster thugs.

Asano Kenichi, Professor of Journalism and Mass Communications at Doshisha University, said that both Ugaya’s and Matsuoka’s cases were worrying signs for press freedom in Japan. “Matsuoka’s arrest has a chilling effect on journalists,” said Asano. “Mainstream journalists may say he is a scandal magazine journalist, so it doesn’t affect them. But if you see the history of Japanese journalism, the police always start with an extreme case. That’s what happened in the 1930s.”

Meanwhile Matsuoka pledged to keep investigating and publishing, despite imprisonment, intimidation, and the indifference of the Japanese media. Speaking at the Foreign Correspondent’s Club, he was candid about the reputation and position of his publications: “Compared to mainstream Japanese media, we are just trash. But if those with political and physical power can squash us, if we can’t publish, that’s suppression of free speech.”

“Lots of people in the mainstream Japanese media think because we are an extreme publication, it doesn’t matter,” he continued. “But that’s dangerous; because if one company can be subjected to this treatment, it creates a precedent for the next person who might not be as extreme.”

Tony McNicol is a freelance journalist and photographer. His work can be seen at www.tonymcnicol.com.

Enjoy the Silence

Lawyers warn that an ‘unprecedented’ lawsuit against a music journalist is a serious threat to press freedom in Japan. So why isn’t the local media interested?

David McNeill

When journalist Ugaya Hiro received a phone call last year from monthly investigative magazine Cyzo, he could hardly have known that his brief conversation with a harried editor would trigger a 50-million-yen lawsuit and propel him into the center of a debate about press freedom in this country.

Nine months after Cyzo published his comments in an article that questioned the accuracy of Oricon magazine’s music charts, Ugaya finds himself in the fight of his life following a decision by the publishing firm to sue him for libel. Win or lose, he will have to pay seven million yen in legal fees.

The freelancer recently spoke about the case at the Foreign Correspondent’s Club with his lawyers, Kamai Eiho and Mikami Osamu and Cyzo Editor-In-Chief Ibi Tadashi. All described the suit as “intimidation.” “The amount they are demanding is outrageous,” Ugaya said. “This lawsuit is for the sake of deterrence.”

Contacted by Cyzo in his capacity as a music critic, Ugaya said that Oricon’s charts — the Japanese equivalent of Billboard’s singles and albums rankings in the U.S. — are unreliable and possibly manipulated. He suggested that Oricon had failed to deal with suspicions that it counted pre-orders of CDs in its rankings.

Industry insiders allege that music companies hype their acts into the charts by pre-ordering CDs, waiting until their song rises in the charts then canceling the orders, by which time they’ve already registered as “sales.” The orders become, in effect, self-fulfilling prophecies.

The subject of the article was Johnny’s Entertainment, the powerful talent agency that has long fended off accusations of dirty tricks. Ugaya had little more than a peripheral relationship with the finished article and Cyzo was not sued. “I was the interviewee, not the writer or the interviewer,” he said.

Ugaya and his lawyers claim he is the first Japanese victim of SLAPP – a Strategic Lawsuit Against Public Participation; a legal maneuver by large corporations to intimidate and silence critics, usually targeting the weakest link in the journalistic chain. Oricon President Koike Koh, who accuses Ugaya of damaging Oricon’s “honor and credibility,” denies the charge of intimidation and says he merely wants a public apology and a retraction.

“If that’s the case, why didn’t they argue their case in print or on their website?” asked Ugaya.

Ugaya’s lawyers fought and won an earlier libel suit brought against a group of Japanese reporters by consumer finance firm Takefuji. Mikami said the Ugaya case is more troubling because Takefuji had targeted writers, not a commentator. “It is unprecedented to sue a person like Mr. Ugaya who has not written the article but merely answered questions on the phone.”

Like the Cyzo editor, Mikami called the implications of the Oricon lawsuit “huge,” explaining that a loss would make it necessary for journalists to issue potential interviewees with a libel warning. “I believe the libel law was designed to protect the rights of individuals,” Mikami said, “but recently we have seen that, on the contrary, politicians and big companies are using lawsuits to prevent and silence criticism.”

Ibi said it will no longer be possible for reporters to do their job if interviewees think they risk being sued. As Ugaya put it: “Who will now answer questions from journalists?”

These concerns are shared by media professionals outside Japan, including Reporters Without Borders, which has asked Oricon’s Koike to withdraw the lawsuit. “The amount of damages requested by Oricon is out of all proportion and would ruin Ugaya,” said the press watchdog. “It is already hard enough to be a freelance journalist in Japan, and this kind of lawsuit jeopardizes journalistic investigation into the activities of private enterprise.”

Given this weighty support and the implications for journalism, some might have expected Japan’s big media to have turned out in strength to hear Ugaya argue his case at the Club. Not so. Not one major local national newspaper or TV company appears to have sent a reporter to the press conference; the handful of TV cameramen at the back of the room were working for small Internet organizations. Apart from wire services like Kyodo and a couple of weekly magazines (notably AERA, which ran a piece on the lawsuit in its Feb. 26 edition) the case has been largely ignored by the Japanese media.

Local reporters can hardly claim they didn’t know about the press conference: Ugaya worked as a staff reporter for the Asahi Shimbun for 17 years and still has extensive industry contacts. Since the dispute erupted late last year, he has been working furiously to recruit supporters and warn about the dangers — to everyone — of losing. He told the press conference the dearth of press interest shows a failure of imagination, not courage. “The press is incapable of imagining the outcome of this lawsuit.”

The theme of the mysteriously absent press corps continued during Ugaya’s first hearing at the Tokyo District Court on Feb. 13. A small delegation of FCCJ members was told there were no press seats available in the public gallery and that a lottery system would decide who got into the courtroom. By the time the journalists arrived 30 minutes before the hearing began all 40 or so seats had been taken, mainly by Ugaya’s supporters and other freelancers.

Ugaya gave what was by all accounts an eloquent opening speech on the importance of being allowed to freely express one’s opinion. Unfortunately, the elite press club journalists in the same building did not see fit to walk the five floors up from their office to hear it. “It’s disappointing,” admitted Ugaya. “They apparently don’t understand this case or press freedom, the principle on which their job is based.”

A spokesman for the Tokyo District Court press club, Yasunori Namiki, who writes for the Nikkei newspaper, denied local journalists were deliberately ignoring the case or that they had felt intimidated by Johnny’s Entertainment. “Because it is up to each news organization or journalist whether to cover the court event, we are not in a position to answer questions about why Japanese journalists did not attend. We cannot dispatch a “representative” of the press club to the court.”

Speaking anonymously, another journalist for a major newspaper said Ugaya’s fight lacked “credibility.” “Frankly speaking, the reputation of the magazine is not so high and the journalist involved is not a member of a major organization. Many of my colleagues would question why they should cover such a case.”

Among the freelance journalists who did turn up on Feb. 13, however, was Egawa Shoko, famously targeted for assassination by Aum Shinrikyo for her investigative work on the cult. She said she came both as a friend of Ugaya and as a working reporter concerned about what might happen if he loses. “Well, I’m also regularly asked to give comments on the telephone,” Egawa said. “Sometimes I get really busy, so if I made a mistake or said something out of turn I would be the person responsible, not the writer or the publisher.”

She said that most of the local media knew about the story but had ignored it. “They don’t think it is their problem, even though it should be, because we could all be in trouble if it goes the wrong way.”

Are the big Japanese newspapers and TV companies slow to rally around a media organization to protect larger freedoms? It certainly appears so. Egawa says most have done little to help NHK in its struggle against government pressure to censor programming. “The other newspapers don’t think this is a problem for the media in general, they think it is a problem for NHK.”

Ugaya says the reason for the media blackout is simpler. “The quality of the reporters is declining compared to 10 years ago when I was an Asahi staffer.” But he also blames the press club system which he says deprives journalists of the “ability to set agendas.”

“They are protected by large news corporations, so they believe this lawsuit belongs to another world: a stupid freelance writer who got into trouble. After many years in a kisha club, journalists lose the ability to “smell” the news because the stories are always provided by the authorities – government, big corporations and so on. When the news is not provided by the authorities, they do not think it news. Or they wait until the authorities “authorize” it as news. My case is a strong proof.”

Ugaya continues to plod a lonely path toward his next hearing on April 3, sustained by the help of colleagues like Egawa and other mainly freelance journalists who have come to his aid. In early February, he launched a 50-million-yen countersuit, calling Oricon’s suit “an abuse of the legal system.” The fact that he has yet to receive a single call from any of Japan’s TV networks will not deter him, he says. “I’m disappointed rather than angry. But this is a matter of justice and freedom of the press for the whole world, not just Japan.”

David McNeill, a Japan Focus Coordinator, writes regularly for a number of publications, including the Chronicle of Higher Education and the Irish Times. These are extended versions of articles that first appeared in the March 2007 edition of the No.1 Shimbun, the house magazine of the Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan. Posted at Japan Focus on March 11, 2007.