What Role Japan’s Imperial Family?

By David McNeill

“Nothing attests more dramatically to the psychological sway of its lingering shadow than the very reluctance of today’s Japanese to debate in public the pros and cons of retaining the imperial family,” says Ivan Hall, a former Gakushuin University professor and author of Cartels of the Mind.

Yet changes are under discussion concerning the imperial succession that raise important questions about the nature and future of the institution. What are the consequences of change? How have other monarchies adapted to a changing world? And what are the consequences of hewing firmly to the present system? Why is it so difficult to have public discussion of issues central to Japan’s future, particularly the character of Japanese democracy?

Few people – let alone a gaijin – get to speak to the son of a living god. So on April 25 this year, I was nervously standing in front of the Emperor and Empress in the Imperial palace, hoping I wouldn’t fluff any of my carefully rehearsed keigo (honorifics). The imperial couple was about to travel to Ireland and Norway and as an Irish journalist I had been granted the privilege of asking two questions.

I wanted to quiz the emperor on his opinion about the compulsory singing of the national anthem at school ceremonies. As I rose to speak, an Imperial Household Agency (IHA) official signaled to the phalanx of TV cameras at the back of the room and they stopped filming and left. “They are worried that as a foreigner you might ask something that might embarrass his majesty,” said the Japanese journalist beside me.

Was this precaution necessary? Everything, from my query, submitted weeks in advance, to his majesty’s written reply had been carefully scripted and vetted by IHA bureaucrats. The whole episode capped to us foreign observers a slightly farcical 60 minutes: journalists asking mostly anodyne questions about their majesties’ health and their impressions of Ireland and Norway before wishing them a safe trip; the sight of 40 heads leaning forward to catch the Empresses’ whispered replies, which could hardly be heard by anyone in the room.

Emperor and Empress: Formal portrait

But my colleague’s point was important. The presence of somebody from outside the system threatens to disrupt the carefully rehearsed dance between the Imperial Palace and the press that covers it. The problem was the IHA had no leverage over people like me: a local journalist could be kicked out of the press club or fired for asking an unscripted question in front of the cameras.

The IHA’s control over their charges is legendary and, sometimes comical. Photographer Toshiaki Nakayama was banned from the imperial household after snapping Prince Akishino’s new bride brushing hair out of his eyes before a formal portrait. One former Imperial House correspondent says he was once admonished by bureaucrats for asking the emperor if he had recovered from a cold. “That’s how much they control things: even a boring [kudaranai] question like that,” says the journalist. “At least if you’re a foreign journalist the Imperial Household Agency cannot harass you.”

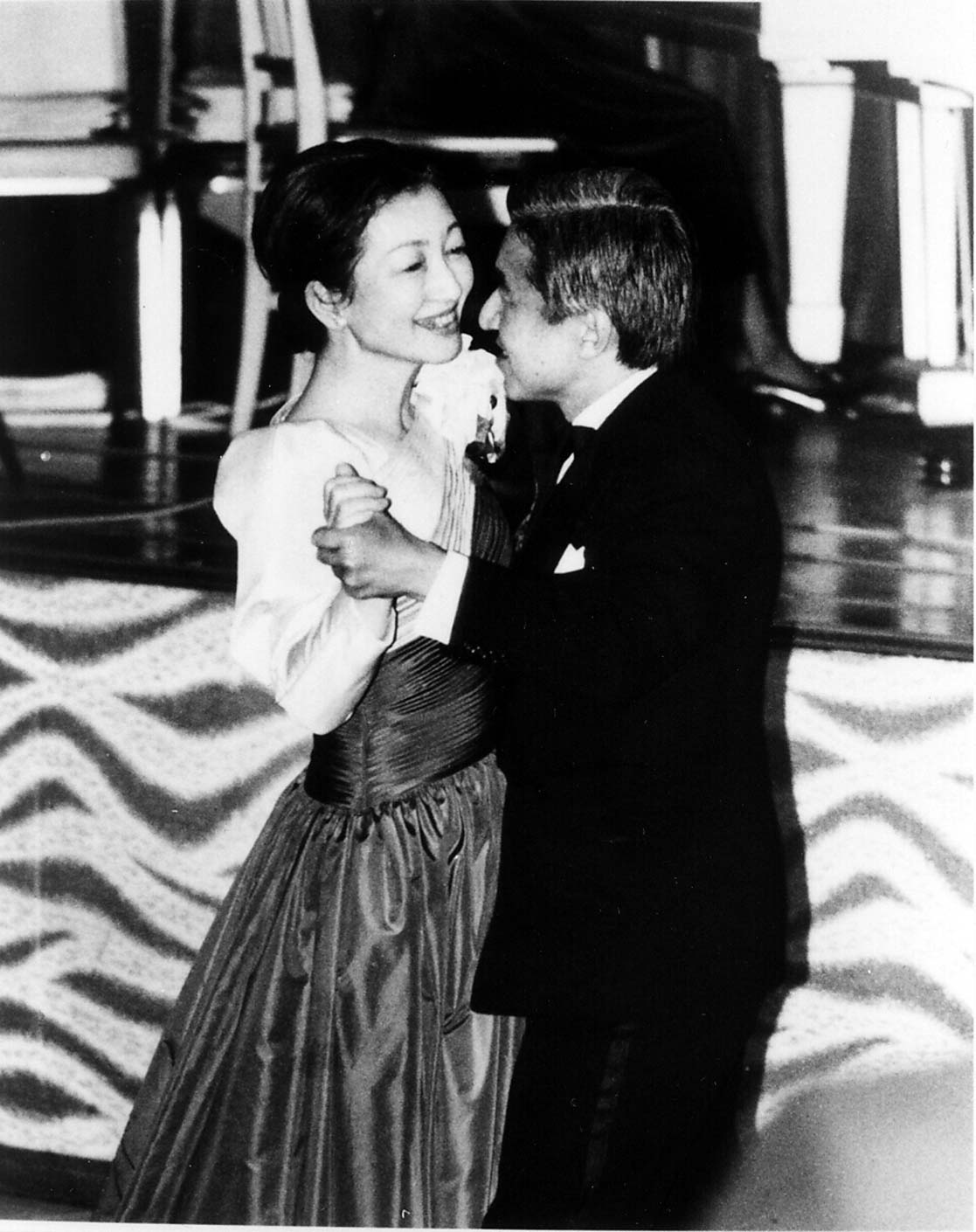

Emperor and Empress at the Foreign Correspondents Club of Japan, 1985

The IHA naturally denies they are all controlling. Spokesman Moriyama Yasuo claims the presence of cameras in press conferences makes their majesties ‘nervous’ and claims there was no question of the cameras leaving the room just because I was a foreigner. “There is a set time for camera coverage of their majesties’ replies and this time simply ran out,” he says, which raises the question: why was I left until last?

This rigid control and the strange institutional taboos that surround Japan’s first family helps explain why the emperor is the elephant in the room of Japanese politics. It is almost impossible in the mainstream media to openly debate the institution’s past, its current role or most importantly its future.

So while a government-appointed panel of experts recently recommended, after months of closed-session discussion, to save the Chrysanthemum Throne from extinction by allowing a female emperor, they avoided the fundamental question: should the institution continue at all?

How much do the imperials cost? What benefits do they bring Japan? What percentage of the population supports them? These basic questions hover around the supposedly 2,600-year-old institution but are seldom openly aired in the big media or in the political arena, despite the unique opportunity offered by the succession debate.

Such questions are of course unthinkable to traditionalists whose views of the emperor verge on the mystical. The granddaughter of wartime leader Tojo Hideki, Yuko, for example, believes that ‘Japan’ would cease to exist without the imperial family. “The emperor is a special existence,” she says. “He is not like normal people. The idea that he is a symbol of Japan as we have been taught in the postwar period is insulting. He is the essence of Japan.”

Tojo Yuko with photograph of Tojo Hideki

But for millions of Japanese, those views are hopelessly out of date. “I think the Imperial Family is an almost empty symbol,” says Kyoto University academic Asada Akira. “It is a symbol of tradition, continuity and stability but one that is devoid of content and almost fabricated. It is a residual, trivial thing.” Some are even harsher. “What are royal families anywhere good for these days,” asks veteran Japan commentator Chalmers Johnson. “Mainly laughs.”

Emperor Hirohito going to the people, 1946

There is no question that the institution is popular. An Asahi Shimbun survey in April 1997, for example, found 82 percent wanted the monarchy to continue with just 8 percent in favor of abolishing it (contrast this with support for the British monarchy which has fallen, according to one poll below 50 percent; see sidebar). Ken Ruoff, author of The People’s Emperor, says polls throughout the postwar period have shown similar results. “Those are remarkable polls,” he says. “Most politicians would be very happy to get results like that.”

In a 1992 NHK poll, however, 32.7 percent said they were ‘indifferent’ toward the first family, a figure that is likely to have increased in the last 13 years. The views of 35-year-old Takeuchi Masanori, a division chief at a Kanagawa construction firm, are fairly typical for men of his generation.

“The emperor probably has merit when it comes to diplomatic issues such as solving political problems in relations with South Korea,” he says, recalling the Emperor’s 2001 speech to Koreans that his roots can partly be traced to the Korean peninsula. “But he means nothing to me. Older people might be upset to lose the emperor, but people like me in their thirties or forties don’t care. But I feel sorry for the family, especially Masako.”

According to a 1999 opinion poll by the Yomiuri newspaper, 24% of respondents had no interest in the emperor and 14% of respondents had no interest in the Imperial Family. Young people were particularly indifferent to the emperor, with 55% of those questioned replying that he did not concern them.

Indeed, to foreign observers one of the most unsettling aspects of the succession crisis is the treatment of Masako. Where is the media and parliamentary debate about her plight – an accomplished professional who has suffered some sort of nervous breakdown under the relentless pressure to have another child?

“This was a career diplomat who wanted to continue her diplomatic work in imperial way,” says Asada. “And she was reduced to a means of biological reproduction. Which I think is awful. She symbolized a new Japanese woman, with a career and position who can speak English fluently and do business abroad. And actually this woman has to be confined in a gilded cage.”

Crown Prince Noriito, Princess Masako, and daughter Aiko

Asada believes the treatment of Masako and the rest of the family is “almost a human rights” issue. “They don’t have a family name, passport, budget, liberty. I think various human rights abuses are going on in the imperial household.”

But how much does this gilded cage cost? Thanks to a 2001 freedom of information law it has been possible to put together a pretty clear picture. According to former Mainichi IH correspondent Mori Yohei, taxpayers funded the imperial family to the tune of about US$260 million in FY 2004, approximately the budget of a small city like Sagamihara. That makes Japan’s monarchy much more expensive than the British royal family, which costs taxpayers about 88 million pounds sterling (about US$152 million a year), according to the Centre for Citizenship.Org.

But while the British royals are personally wealthy – Queen Elizabeth is one of the world’s richest women and Prince Charles inherited a 144,000-acre estate – the Duchy of Cornwall – on his 21st birthday – the Japanese imperials had most of their wealth confiscated after World War II. The Showa Emperor left 2 billion yen in stocks and cash when he died and Mori estimates that his son has just five million yen a year to spend on himself.

The Japanese imperials, in other words, are like well paid bureaucrats without many of the frills that most European royals take for granted.

Japanese taxpayers pay for the six core members of the Imperial Family: (Emperor, Empress, Prince Naruhito, Princess Masako, Princess Aiko and, before she left in November 2005 to marry a commoner, Princess Nori); 19 other family members live in residences provided by the state. The budget also pays for about 1,000 Imperial Household Agency staff: a 24-piece orchestra, 160 servants, 25 cooks, four doctors and a cellar stocked with 4,500 bottles of wine. The Agency runs properties around Japan, in Naha, Kyoto, Gifu, Tochigi and elsewhere; a total of 24.66 sq. km. of property, or about double the area of Chiyoda-Ku (11.64 sq. km).

When it comes right down to it, says Mori, the Heisei Emperor and his entourage costs every person in Japan about 214 yen a year, or about 1000 yen per family. Put it like that, and it doesn’t sound that much.

But Mori, who says he wrote his book to ‘atone’ (hensei) for failing to do his job as an IHA reporter, says the cost is likely to rise if the current succession laws are changed – a point seldom raised in the succession debate.

“If they allow an empress, the size of the imperial household will naturally rise increasing the burden on the taxpayer…potentially the number of new members is limitless.”

More continued: “The experts panel advising the Prime Minister says the number of Imperial Family members will be kept within reasonable limits through a flexible system of withdrawing imperial status. But in reality, I don’t think any members of the Imperial Family, whose livelihood is guaranteed by the state, are going to volunteer to become commoners. They are likely to resist the change in their status leading to a limitless expansion in the size of the Imperial Family.” He believes that those women who used to leave the Imperial Household at marriage will now stay on board and be joined by fresh blood from outside the family; another reason why he thinks the time has come for abolition. “Fundamentally, I don’t think we need them. Historical and culturally, they no longer have a purpose.”

How then does Japan benefit from the imperial presence? Supporters tend to cite the emperor’s diplomatic role as an ambassador for Japan abroad, although his father’s controversial role in the Pacific War means the institution is forever tainted in Asia.

Like their British counterparts, supporters also stress ‘tradition’ and the emperor system as a ‘source of stability,’ a key reason why Japan was able to make the postwar transition to peace and economic prosperity, says conservative cultural critic Yawata Kazuo, author of “Oyo-tsugi” (Imperial Succession): “In addition to economic growth, the reason for the success of postwar Japan is that the Japanese gathered around the Imperial family, who have long historical tradition, to create a peaceful state. The value of the Imperial family lives in its beneficial contribution to Japan’s stability.”

Suzuki Kunio, the central figure of the new-right and a former chairman of Issuikai, an ultranationalist organization dedicated to overthrowing Japan’s postwar system, considers the emperor Japan’s ‘spiritual core,’ binding the country together in times of crisis. He believes the status quo is better than the alternative, such as republicanism. “If the emperor became a private citizen, there would be a lot of moves to create political parties, and cultural or religious organizations alongside him. The Emperor could run for public office and become a much stronger presence than in the current system, in which he has no political power.”

But Ruoff is one of many who believes these arguments are out of date. “Historically the imperial family was the center of national unity. Does Japan need this central force now? It has no linguistic divide, no cultural divide; it doesn’t have any political divide that would split the country, such as a civil war. Do they need this symbol of national unity? No.”

Ivan Hall goes further, calling Japan’s monarchy: the “ultimate linchpin of the myth of Japanese uniqueness and the lodestar for the most repressive ideas of racial superiority.” He says keeping it around gives the ultra-right its sense of legitimacy, a belief shared by Pulitzer-award winning author Herbert Bix, who believes massive reform is needed to bring the family into sync with modern Japan.

“Consider how marital patterns and lifestyles have changed since General MacArthur, for his own short-term political reasons, had the monarchy written into the Constitution of Japan. Today marriage occurs late, divorces are frequent, women have fewer children, and they work after marriage. Conversely, men increasingly take part in child rearing and contribute to housework.

“In this twenty-first century society, with its diverse male and female lifestyles, the imperial family can no longer function as a model, let alone a symbol of national unity…The imperial institution is totally out of sync with the times.”

For most commentators – right and left – the key issue is openness, a quality many see lacking in the current debate about changing the Imperial Household Law. Suzuki calls the obsession with protecting the unbroken bloodline meaningless because it has already been broken. “The important point is not whether there is a king or Emperor, but whether democracy is being fully practiced or not,” he says.

To many, there was little democratic about the way the female succession issue was decided: a hand-picked team of elite government advisers reporting to the prime minister with no remit to discuss the wider role of the monarchy, its costs and benefits, or its future. Documentary filmmaker Mori Tatsuya says Japan knows only too well the dangers of allowing a remote monarchy to be politically manipulated. “There is a long history of ambitious people using the emperor system for their own ends which reached its peak in the Pacific War.”

But he sees no need to abolish it, as long as it is made open and accountable. “My metaphor for the Imperial Family is the appendix. Most of the time it has no function and you can cut it out when you’re young, although this can have some sort of harmful [hormonal] affect. But, if it is going to be allowed to continue it should be on the assumption that we have freedom of information and a system of accountability for the emperor. If we assume that, the emperor is just a decoration (kazari) so why not keep him?”

The bureaucrats who surround the emperor are of course well aware of the need for more openness, but they fear where it will lead. Many look with astonishment at the price paid by the British monarchs for more openness in their search for popularity.

Thirty years ago, Buckingham Palace was also a taboo-laden institution treated with kid gloves by the media. Few British knew that some members of the royal family supported fascism; that Prince Phillip is a racist, or the rumor (reported in Kitty Kelly’s book on the Windsors) that Queen Elizabeth, like Princess Aiko, was conceived through artificial insemination.

Today, most British people have heard stories of Princess Diana’s bulimia, depression and affairs; of Princes Charles’ adultery and his infamous cellular call to Camilla, reprinted in a newspaper, in which he fantasized about being her tampon. For IHA bureaucrats who live to protect the dignity of the imperial institution, the fate of the British royals is a horror story.

Some British people hark back to a golden age when they lived in ignorance of what went on behind the gates of Buckingham Palace, but most would rather know what their money is paying for. The Japanese public seems much less informed about what goes on behind the Chrysanthemum Curtain thanks to the complicity of the press. One former correspondent says he agrees that journalists help protect the “mystery” (shimpiteki na bubun) of the Imperial Family. “But no matter what we do the family will have to reform. And the more they reform the more the mystery will decline. That’s their dilemma.”

Reform, abolish or, worst of all, it seems, stay the same. What will the Imperial House do? Ruoff wonders what good would come out of abolition. “They could turn the palace into a public park, they could run the subway under the park. Symbolically it would be important: why should this family get this handout. It would take away this national symbol for the annoying far right, but they would just come up with something else to worship.”

But he points to something often lost in the fog that surrounds Japan’s most conservative institution: the emperor could not survive without public support. “He is essentially required to be the people’s emperor. If the people do not want the throne, it will be abolished. This royal family has got to maintain its popularity and they do that by reaching out to people as much as they can.”

Amid all the concern for Article 9 of the constitution, few seem to linger over article 1: “The Emperor shall be the symbol of the State and the unity of the people, deriving his position from the will of the people with whom resides sovereign power.” Will it forever be so?

My question to the emperor

This question is addressed to His Majesty The Emperor. According to a survey implemented by the Yomiuri Shimbun, the majority of students today have no interest in singing the national anthem or raising the national flag in ceremonies. In the autumn of last year, Your Majesty made a statement yourself in this regard. Please tell us your thoughts on the obligatory singing of the national anthem and raising of the national flag in schools].

Response:

World’s countries have their national flags and national anthems and I think it is important that respect for national flag and anthems be taught in schools. The national flag and national anthem are considered to be symbols of the nation and the feelings of the people towards them should therefore be valued. At the Olympics, there were a number of Japanese medal-winning athletes who took the national flag of Japan with them on their lap of victory. There is nothing forced about the happy face of an athlete. What is desirable is for each and every person to think for himself or herself about the national flag and anthem.

Countries that have abolished their monarchies – and have managed to survive

While Japan clings to its system of ancient hereditary power, Europe has been binning or modernizing monarchies for years.

Take the Italians. The House of Savoy claimed almost 1000 years of tradition, but that did not save King Umberto, who paid the price for supporting Mussolini’s fascists. In a 1946 referendum, the Italians voted to abolish the monarchy and send the king and his family into exile.

For good measure, the government banned the king’s male descendents from reentering the country until three years ago. Umberto’s grandson Vittorio Emanuele touched down in December 2002 and indicated he was ready if the Italians wanted him back. The Italians sniffed and said: no thanks.

King Constantine of Greece, one of Europe’s most popular royals, should have been taking notes. Instead he clashed with the Greek government in the 1960s and was widely blamed for the chaos that followed. The public rewarded him by abolishing the monarchy in a 1974 referendum. As the poll results came in, Prime Minister Constantine Karamanlis famously announced that “a carcinoma” had been removed from the body of the nation.

The state awarded the ex-king 4 million Euros in compensation for his 550 million Euros in confiscated assets. Constantine still refuses to recognize the Greek republic, is banned from owning a passport and has become a figure of ridicule. Many public figures openly mock him, calling him the ‘half-wit king’ and “o Teos” (“the former”).

Germany, Portugal, Hungary, Turkey and Romania have also waved goodbye to hereditary rule over the last century. Bulgaria threw out its king, Simeon Saxe-Coburg-Gotha in 1946 then much later elected him prime minister, making him one of aristocracy’s rarest figures: a born-again democrat. But other countries have debated abolition and decided against it, and at least one country – Spain – has restored its monarchy.

The Spanish ditched their king in 1931 but decided to invite his successor back in 1975: many Spanish saw him as a liberal beacon during the long years of fascist rule under General Franco. When Franco died, King Juan Carlos I was put back on the throne, although his power is today largely symbolic – more presidential than monarchial.

Those European monarchs still occupying tax-funded palaces know they must court popularity or die. In England, politicians now openly discuss downsizing Queen Elizabeth and her increasingly unpopular, dysfunctional family. Support for the monarchy, according to some polls, has fallen below 50 percent and a 2001 Observer newspaper poll found that only 43 percent of British subjects expect the monarchy to still be around in 2051.

Republicans criticize the Queen’s enormous inherited wealth and say Britain will never wipe out its stifling class system until it gets rid of the family that sits at its peak. Supporters say the monarchy must be kept in the interests of English ‘tradition’ although cynics say the Windsor’s family tree is not English at all: the Queen’s husband Prince Phillip is Greek, and the family’s roots are German: they changed their name to Windsor from the German-sounding Saxe-Coburg-Gotha during World War I.

Royalists also like the idea of the hard-working Queen as Britain’s figurehead, and say tourism would suffer if the Windsor family was put out to pasture, but critics point out the former palaces of the guillotined French royal family are bigger tourist attractions and wonder what the world will make of the queen’s successor, King Charles.

So far, these debates have yet to congeal into a popular republican movement. In the meantime, the press, which was almost as deferential as its Japanese counterpart until two decades ago, has taken the gloves off. Stories that used to stay behind the palace walls, such as adultery, homosexuality and extravagance, have come tumbling out.

Some British modernizers say to survive the Windsor family must copy the European models for a modernized monarchy. Denmark’s chain-smoking, easy-going Queen Margrethe, for example, runs an open, low-maintenance institution, gives her own press conferences and can at least pretend to make a living: she works as an artist and illustrator, designs costumes for TV shows and sells her paintings for charity. The Dutch imperials – once notoriously publicity-shy – have been forced on the defensive by a series of press revelations following accusations of dirty tricks by Princess Margarita de Bourbon Parme, Queen Beatrix’s nice.

Is this where Japan might be headed? In 2002, a journalist asked Empress Michiko if she could ever see Japan imitating the so-called ‘bicycling monarchs’ of Denmark and Holland. “I like riding a bicycle,” she said. “But the traffic in Tokyo is so heavy that I think I would be scared, and probably make people around me nervous too.”

The Furyu Mutan Incident, the media and the Imperial Family

In 1960, Fukazawa Shichiro dropped a bombshell on Japan from which it has never quite recovered.

In December of that year, Chuo Koron published a Fukazawa parody called “Furyu mutan” in which the narrator has a dream that leftists take over the imperial palace and cut off the heads of Crown Prince Akihito and Princess Michiko in front of an enthusiastic crowd. After watching the imperial heads roll, the narrator has an angry exchange with the Meiji Emperor’s wife.

The dowager empress tells him he owes his life to the Showa Emperor who “saved the country” by surrendering unconditionally on August 15, 1945. “How can you say that, you shitty old hag?” says the narrator. “Damn you! (Kon Chikushou!). Our lives were saved because people around your grandson persuaded him to! Unconditionally!”

The satire – unthinkable today – provoked fury in the Imperial Household Agency, which tried to sue the author and publisher, and among ultra-nationalists, who demonstrated daily outside Chuo Koron’s Tokyo offices. Finally, on February 1, 1961, a seventeen-year-old rightist broke into the home of Chuo’s president, Shimanaka Hoji, killed a maid with a sword and severely wounded Shimanaka’s wife.

The Furyu Mutan incident was for many a watershed in postwar Japan with devastating consequences for the freedom of the press. It was an ”epoch-making thing, a turning point from fairly open debate about the emperor to implicit taboo about the emperor,” says Asada Akira of Kyoto University. “It was much more common to question the existence of the emperor before then.”

Fukazawa went into hiding, Shimanaka apologized repeatedly, Chuo Koron pulled in its horns and other publishers followed suit. Bungei Shunjyu baulked at publishing the follow-up to Kenzaburo Oe’s anti-rightist novel, 17, and no mainstream publisher ever dared to publish such a satire again.

Ironically, Fukazawa wrote the piece to warn about the radical left, according to the editor who replaced Shimanaka at Chuo Koron. “It was a story about the terror of revolution but what remained in the mind was the visceral image of the crown prince and princess’ heads flying,” says Kasuya Kazuki, who helmed the magazine until 1978. “It was a mistake to publish such an inflammatory article during what was a revolutionary situation in Japan. The article itself was the problem, not the reaction to it.”

The incident and the fear of the ultra-right generally, help explain why the Japanese media has since trod so carefully around the Imperial Family. Mainstream journalists, hemmed in by the imperial taboo, seldom write anything today not officially sanctioned by the Imperial Household Agency. Over the years, the foreign media has repeatedly scooped Japanese journalists who know they could never get such stories past their own editors.

It was the Washington Post that first told the world about Princess Masako’s engagement to Crown Prince Naruhito in 1993, after the local media had sat on the story for months. It was the London Independent that suggested in 2001 that Princess Aiko was the product of in-vitro fertilization, although the story was widely rumored in Japan. And it was the Times that first carried a story about Princess Masako’s illness on May 21, 2004, called “The Depression of a Princess.”

Foreign publications have found it easier to parody Japan’s first family. Over the years, the British press has carried vicious caricatures of Emperor Hirohito, including several as he lay slowly dying in 1989. Germany’s Sueddeutsche Zeitung’s sparked a furor in 2001 when it carried a cover picture of Prince Naruhito with the words Tote Hose – literally “dead trousers” – printed over the prince’s crotch.

Japanese journalists, frustrated at the limits of their jobs, are often the source of foreign scoops. The Imperial Household Agency correspondent for a major Japanese newspaper said: “I probably put in writing less than one-tenth of one-percent of what I see and hear. For a writer, that’s a kind of torture.” The implication was that self-censorship was central to the job. Inevitably, some journalists pass on what they know to people like the Times correspondent Richard Lloyd Parry

“Japanese journalists knew all about Masako’s illness and it didn’t surprise any of them when we spoke to them,” says Parry. “So why didn’t they run the story? In my view it’s because of the strange institutional taboos that still surround the Imperial Family, which are very murky and not rational and which have a lot to do with Japan’s war and postwar history. This period has not been properly dispelled or digested. There is still unfinished business.”

Parry says over the years Japanese journalists who follow the imperial household have been ‘very helpful’ in pointing him in the direction of stories “they know they can never get published in their own country.”

Once the story breaks outside Japan, the Japanese media get to have their cake and eat it: they can cover the story freely and criticize the foreign press for breaking the rules. Furutachi Ichiro, the anchor of Asahi’s Hodo Station, was one of many commentators who slammed the Times for reporting on Masako’s personal problems. But Parry and others believe the public had a right to know.

“The fact that the person most likely to produce a male heir, amid a succession crisis, was ill meant that the public interest was at stake,” says Justin McCurry, the UK Guardian’s correspondent in Japan.

Some argued that Masako’s problems were personal, but Parry says he took that into consideration. “We heard about Masako’s illness in January 2004 but decided not to use it because we felt it was a personal matter. But in May when her husband blamed the Imperial Household for her illness, the question was in the public domain, and you couldn’t understand the story fully until you got the rest of the information. So at that stage we decided to run it.”

Documentary filmmaker Mori Tatsuya agrees: “The imperial family lives on our taxes and Masako is a future first lady, so if she gets sick it is important that we know about it.”

As in the UK and other monarchies, of course, there are journalists and editors who believe it is their job to protect the monarchy from dishonor, even if that means excluding other journalists from covering it. “The IHA is right to be careful of who they allow in, including foreigners,” says Chuo Koron’s Kasuya. “They can’t just let any clown [doko no uma no honeka mo wakaranai] ask his majesty a question.”

This is a modified version of an article that appeared (in Japanese) in Newsweek Japan on December 7, 2005. Posted at Japan Focus on December 16, 2005.

David McNeill is a Tokyo-based journalist who teaches at Sophia University. A Japan Focus coordinator, he is a regular contributor to the London Independent and a columnist for OhMy News.