The Art of Chindogu in a World Gone Mad

By David McNeill

Kawakami Kenji’s weird inventions have brought him notoriety in his native Japan and in Europe, where some call him a surrealist genius and even a neo-dadaist. But there is method in his madness.

Let’s be frank. Kawakami Kenji looks a bit barmy: hooded eyes staring unnervingly beneath what appears to be shaved eyebrows, topped by an unruly mop of spindly hair. And this is before he happily poses for photographs with a toilet-roll dispenser on his head. “It’s for sufferers of hay fever,” he explains. “They blow their noses a lot.”

We are in Kawakami’s pokey office in central Tokyo, which is messier than an art student’s apartment, thanks to his weird inventions – a total of 600 dreamt up over ten years. Everywhere there are things that look like props from a Monty Python show: duster slippers for cats, self-lighting cigarettes, a portable zebra crossing, a double-headed toothbrush.

Some of the inventions look vaguely useful: I quite fancy the noodle cooler (a fan stuck to a pair of chopsticks), although actually using them outside the house invites a visit from men in white coats. But ridicule is grist to Kawakami’s philosophical mill: “If people laugh, that’s fine,” he says. “We need more of it. I believe in rejecting society by laughing at it.”

Humor is part of the art of Chindogu, which translates roughly as weird or unusual tool, but which some have dubbed “The

Japanese art of useless inventions.” The Chindogu movement has become something of a cult since Kawakami founded it over a decade ago and began publishing his ideas. Pictures of his inventions have been popping up in office e-mail inboxes for years, along with snaps of their poker-faced creator, often wearing them on his head.

Now boasting nearly 10,000 practitioners worldwide, according to Kawakami, there is even an International Chindogu Society run out of the US (http://www.pitt.edu/~ctnst3/chindogu.html.). Art critics have joined the ranks of Chindogu fans, praising its founder as a Zen satirist of consumer society, and Chindogu exhibitions are often staged around the world. In the US, however, the finer points of his critique of capitalism are sometimes lost. “Chindogu is considered radical in other parts of the world,” says Kawakami. “But in America they just laugh at the weird Japanese inventor.”

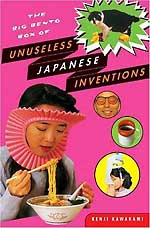

Kawakami’s books, which have sold about 200,000 copies in Japan, have been translated into English (101 Unuseless Japanese Inventions: The Art of Chindogu and 99 More Unuseless Japanese Inventions, both published by WW Norton & Co.), French, Chinese, German and Spanish, and he makes regular appearances on the BBC and other European TV stations. Barely a month goes by without a media invitation coming through the fax machine, along with diagrams for banana-openers, spaghetti-cutters and portable toilet seats from Chindogu enthusiasts around the world.

Kawakami himself, tongue firmly buried in cheek, says his creations are “strangely practical and utterly eccentric inventions designed to solve all the nagging problems of domestic life.” When he is being serious he will describe them as “invention dropouts,” ideas that have broken free from “the suffocating historical dominance of conservative utility.” “I describe them as unuseless. Technically they are convenient and you can use them but most won’t because of shame.”

It all seems like harmless fun, but Chindogu has a serious philosophy and set of rules. The inventions cannot be for real use, for example, but they must work, and they cannot be patented or sold. And humor must not be the only reason for making a Chindogu. It also helps a lot if you have the spirit of an anarchist and hate the way the world is run.

“I despise materialism and how everything is turned into a commodity,” says the 57-year-old inventor, while chugging on the first of an endless supply of cigarettes. “Things that should belong to everyone are patented and turned into private property. I’ve never registered a patent and I never will because the world of patents is dirty, full of greed and competition.”

So opposed is he to getting his hands dirty with filthy lucre that Murakami waives the interview fees many professional authors charge in Japan and gives the money he makes from his books and articles to his favorite causes. He says he began small, publishing his photos as a hobby in magazines (he still runs a small publishing business) before being inundated with requests for articles and then books. “I made little money from the inventions” he laughs. “I did the photos myself, so I had to find models, and pay for the printing and packaging. But I’d like to make more and set up a foundation to rid the world of landmines. Look at how the big powers create weapons that hurt little innocent people. I hate that.”

This has not stopped others from stealing his ideas, including his two-sided slippers, which can be found retailing for 1000 yen on the shelves of a well-known Japanese chain store. “Some people have no principles,” he says in disgust. “They’ll do anything for money.”

Kawakami’s anti-materialism appears genuine: He has the casual everyman look of an off-duty corporate worker and has not changed the oversized glasses he has worn for years. He is not married and has no children to send to private school. The only apparent concession to bourgeois luxury is the old 7-series BMW that sits outside his office, but a thick layer of dust makes it clear that the car has not moved in years. “I’m not much of a driver,” says its owner.

It’s at times like this that Kawakami sounds most like the radical young activist he once was, one of thousands in Japan who graduated from student politics in the sixties to direct action in the seventies and eighties. The key issues were the Vietnam War and Japan’s subservience to capitalist America, but after years of guerilla-style violence against the authorities the movement eventually became dominated by small leftwing sects and turned in on itself, consuming dozens of former radicals in deadly sectarian disputes. About 100 activists were killed in what was called uchigeba, or internecine warfare among the sects. Many more resigned themselves to life in the system they fought. Kawakami decided to lampoon it, after what one can only imagine was a very unhappy spell as editor of a home-shopping magazine.

“I’m an extremist,” he says. “I believe we have to do extreme things to make people think about this society and to question common sense. I want people to question everything because they don’t think and analyze any more. How else could they have elected a president like that in the United States? He’s an idiot. But I think my generation failed to change the world. I don’t regret fighting the system but I regret that we ended up fighting ourselves. We set a bad example for the young, which is why today they don’t have a clue about what is going on.”

Although most of his radical energy now goes into his inventions, Kawakami’s hatred for America, and its subservient Asian ally, is undimmed. “In Europe they treat me as an artist, a new Dadaist [after the early twentieth-century art movement that held irrationality and anarchy as the only rational responses to a world gone mad]. In Australia and Canada, I’m called a scientist. In China and Hong they wonder why I don’t try to make money from my inventions. But in Japan and the US, they consider me a maker of party goods. People have been trained not to think in Japan and America. I think it’s quite natural to hate America, its lack of logic and its brutality. But Japan is pitiable too, the way it follows everything the US does.”

In the meantime, the world’s Chindogu enthusiasts wait for Kawakami’s next book. Can he top the Drymobile (a clothesline attached to a car) and the Hold-It Helmet (a hat with a clipboard to allow reading on the move)? Their crackpot creator, who calls himself a purveyor of “invention art,” is confident. “I think my things show us our stupid obsession in Japan and America with making life as easy as we can with a new thing. Everybody has the ability to create. We just have to free our imaginations. The problem is that this society destroys out ability to think. We have to get this ability back.”

David McNeill is a Tokyo-based journalist who teaches at Sophia University in Tokyo and is a regular contributor to a number of publications, including the London Independent and the Irish Times. He is a Japan Focus Coordinator. This article originally appeared in the Independent as on May 18, 2004 and is published in a slightly edited version at Japan Focus on August 24, 2005.