Snakes and Ladders for Japan in Indonesia’s Energy Puzzle

David Adam Stott

‘Possibly the most important (challenges) are Indonesia’s declining oil and gas production and the fast increasing domestic requirements for oil and gas; the persistent electricity and petroleum subsidies and price controls; and the limited clarity in Indonesia’s energy sector governance, co-ordination and decision making regime.’

International Energy Agency (IEA), Energy Policy Review of Indonesia (2008)[1]

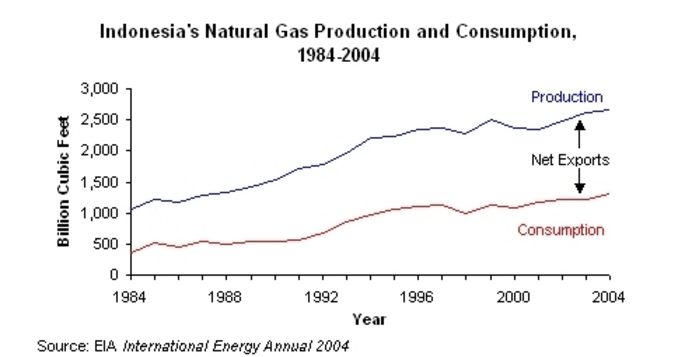

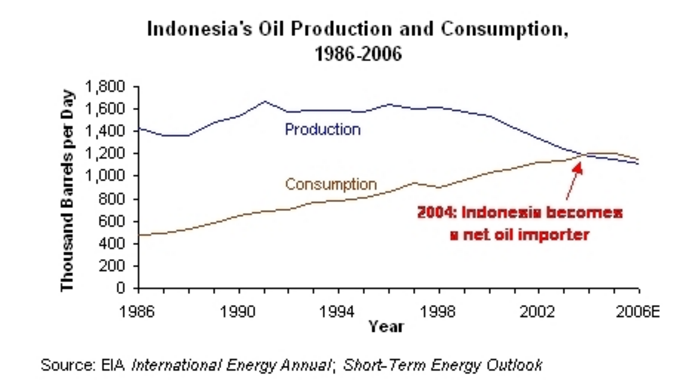

The Asian liquefied natural gas (LNG) industry is undergoing a major realignment. Whilst regional LNG demand continues to increase, Indonesia has relinquished its position as the world’s biggest exporter and is redrawing its energy export policy to reflect evolving priorities and changing circumstances. Indonesia became a net importer of crude oil in 2004, a costly encounter with reality for a country accustomed to domestic energy subsidies. A consequent lack of investment in energy infrastructure has resulted in both industrial output and overall quality of life being compromised by electricity shortages. The central government has responded by phasing out exports from its biggest LNG processing plant and prioritising supplying the domestic market. At the same time, Jakarta continues to promote foreign investment in new gas projects, albeit amid high levels of policy uncertainty.

Nevertheless, Japanese firms are behind moves to double the number of LNG processing plants in Indonesia to six within the next five years. Japan keenly feels any change in Indonesia’s gas export policies since it is the world’s largest importer of LNG and Indonesia’s biggest customer. As long-term contracts with Indonesia expire, Japanese buyers have been scrambling to secure replacement LNG supplies from the archipelago and elsewhere. Despite all the maneuvering, Indonesia remains attractive to Japanese energy firms due to its relatively proximity and its sheer size.

Five specific LNG projects are being affected by Jakarta’s energy policy reforms. This paper will firstly analyse the reasons for the policy change before presenting an overview of these five schemes. In doing so, other related aspects of Indonesian energy policy – such as fuel and electricity subsidies, the prospects for unconventional gas and the general foreign investment climate – will be assessed. In essence, this paper will seek to address the issues cited above by the IEA by focusing on LNG ties with Japan.

Most of Indonesia’s LNG plants are located far from its population centres. Sengkang, Senoro and Abadi have yet to start production.

Indonesia’s energy reforms

LNG processing plants are where natural gas is liquefied and compressed for transport, and are usually located near the natural gas fields, from where the gas is transported to the plant through pipelines or by freight transport. During processing, impurities in the gas are removed, and it is then cooled to minus 162C and kept in cryogenic storage. At such temperatures, natural gas becomes liquid and 615 times smaller in volume. The coolness also ensures that is not explosive and does not burn. The LNG is then sent by specially constructed double-hulled ships to an LNG receiving terminal, where it is reheated and subsequently distributed to the buyer.

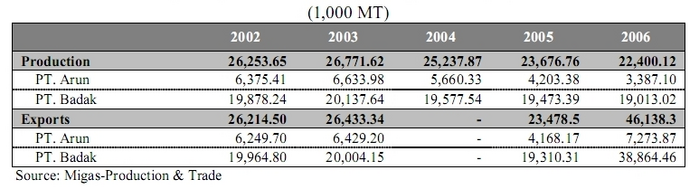

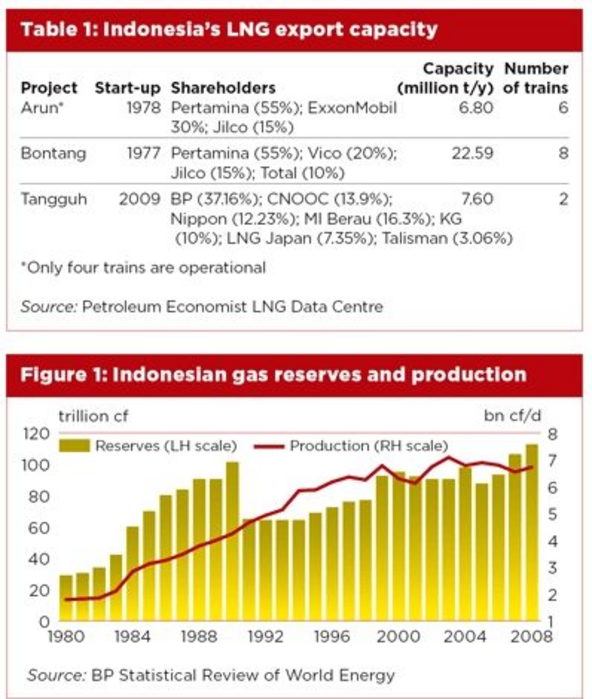

Indonesia became the world’s biggest LNG exporter from two processing plants – the ailing Arun facility in Lhokseumawe, Aceh province and the Badak plant in Bontang, East Kalimantan province – built under long-term supply contracts with Japanese buyers and opened in the late 1970s. The country’s third such plant, the Tangguh facility in West Papua province, opened in May 2009. Prompted by becoming a net oil importer in 2004, the Indonesian government now wants to replace costly oil with gas-fired power generation, and the expiry of these long-term LNG sales contracts will help them to do so. Natural gas that has long been destined for export will instead be sold domestically, bolstering Indonesia’s energy security and reducing reliance on oil imports. Since most of the country’s LNG exports end up in Japan, Japanese utilities will be the biggest victims of this policy reversal. Indonesia presently supplies about 20% of Japan’s total LNG imports, although this share has been steadily eroded as Qatar, Malaysia, Australia and Russia catch up. Nevertheless, Indonesia’s geographic proximity to the large LNG export markets of Japan, South Korea, Taiwan and, increasingly, China, guarantees its attractiveness to Northeast Asian developers and buyers.

Whilst several new LNG projects are in various phases of development, the Bontang LNG plant remains the jewel in the crown of Indonesia’s oil and gas industry. Despite being surrounded by ageing gas fields, upgrades to the processing plant and continuing exploration have ensured that Bontang is still the source of around 90% of Indonesia’s LNG exports to Japan. Indeed, the combined processing capacity of all of Indonesia’s new LNG projects will still fall short of Bontang’s annual output, at least in the initial stages of these new projects. Therefore, it was with dismay that Japanese customers greeted Jakarta’s decision to phase out exports from the East Kalimantan plant, especially since Japan is the largest bilateral lender to Indonesia, having provided loans totalling US$22.3 billion, which accounted for 43.2% of the Indonesia’s total external debt in 2009.[2] To understand this policy change it is necessary to examine certain economic, demographic and geographic realities in Indonesia.

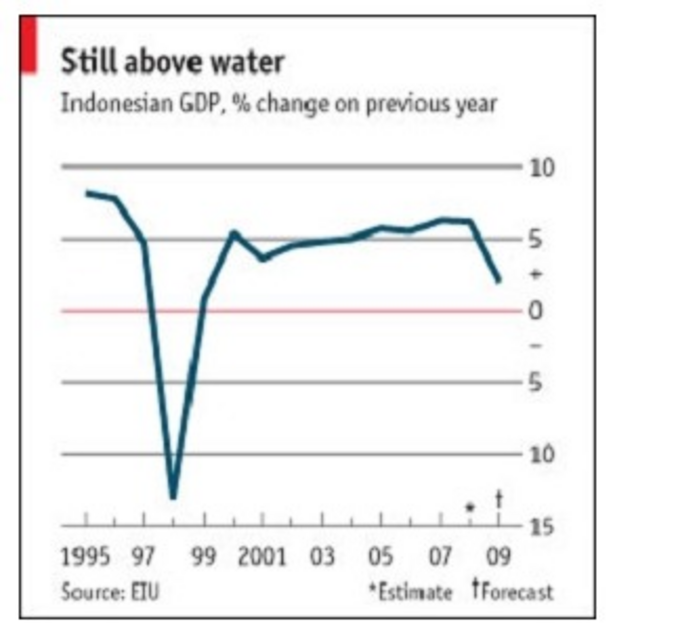

To keep pace with economic expansion and population growth, Indonesia requires ever greater amounts of oil and gas. Since recovering from the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997-98, the country has achieved consistent economic growth of 5-6% per annum, driven by a steadily expanding services sector. As the role of manufacturing and services in the economy increases, so does the country’s energy requirements. The service sector, encompassing trade, finance, transport, communication and construction, grew at about 8% per annum for several years before the Global Financial Crisis. Despite the Crisis, this sector still managed to grow 5.9% in 2009, almost double the growth rate of agriculture, mining and manufacturing. Consequently, the service sector accounted for 51.9% of Indonesian GDP in 2009, up from 48.9% in 2006.

The result is a dramatic increase in domestic gas demand. Government statistics report that industrial gas consumption rose from 3,541 million metric standard cubic feet per day (mmscfd) in 2005 to 4,233 mmscfd in 2009. The country’s fertiliser, ceramics and electricity industries are the biggest contributors to this rising demand, projected at 2.8% per annum to 2020. As investment in both production and distribution infrastructure has failed to keep pace with this extra demand, industrial and residential consumers have experienced increasingly scarce gas supplies.

To cover shortfalls in gas output from Aceh province, for several years gas has been diverted from Bontang so that Pertamina can supply a national fertiliser manufacturer and two small Japanese-owned fertiliser plants. The expiry of long-term sales contracts with Japanese utilities allows the central government to formalise this process and consolidate fertiliser supplies, thus boosting the agricultural sector. Government policy makers also see Bontang ameliorating electricity shortages and fostering economic growth by furnishing manufacturing industries with affordable gas supplies. Therefore, more of the Bontang output will instead be delivered to the West Java Floating Storage Regasification Terminal (FSRU) being constructed in Jakarta Bay to receive the LNG, which in turn will supply electricity to the capital and its hinterland. In October 2010, Japanese firm Inpex signed a preliminary sales agreement to supply 11.75 MT of Bontang LNG to the West Java terminal between 2012 and 2022. BPMigas has also stated that the Tangguh plant could supply 0.5 to 0.7 MT per annum to the West Java FSRU. The central government is also planning a further two LNG receiving terminals to supply Surabaya and Medan, the country’s second and third cities respectively.

Electricity shortages are a major concern as state electricity monopoly PLN struggles to cope with increasing demand. The country needs some 260-290 billion kilowatt hours (kwh) to avoid rationing and rolling blackouts, but in 2009 electricity output was only around 170 billion kwh, and demand is constantly rising. It is estimated that every 1% of future GDP growth will require a simultaneous 2.5% rise in electricity output. Given that the Indonesian economy grew at an annual rate of 5.7% in the first quarter of 2010 and 6.2% in the second quarter, to sustain such growth the country needs to bolster its electrical power output by at least 15% each year.[3] Indeed, in 2008 shortages prompted a group of Japanese firms, backed by the Japanese Embassy, to threaten to leave Indonesia unless electricity supplies were improved. The Jakarta Japan Club cited a survey of its 414 members throughout the archipelago which put these firms’ combined losses due to power cuts at some US$4.44 million. The other major complaint of these firms, mainly operating in chemical industries, precision parts and tyre manufacturing, was the lack of advance notice from PLN which would enable them to tailor operations around the blackouts.[4] In order to increase electricity generating capacity, Indonesia will divert gas that was previously destined for export, thus harming Japan’s domestic energy security but benefitting Japanese firms in Indonesia.

Rapid population growth exacerbates such shortages. The results of the latest nationwide census conducted in 2010 showed 237.6 million people in the country, up from 205.1 in 2000. This increase of 32.5 million people equates to average net population growth of 1.49% per annum during the last ten years, meaning that in the last 80 years Indonesia’s population has more than tripled.[5] Naturally, such growth threatens the government’s development targets in education and healthcare, increases pressure on Indonesia’s creaking infrastructure and challenges the economy to provide ever more employment opportunities.[6]

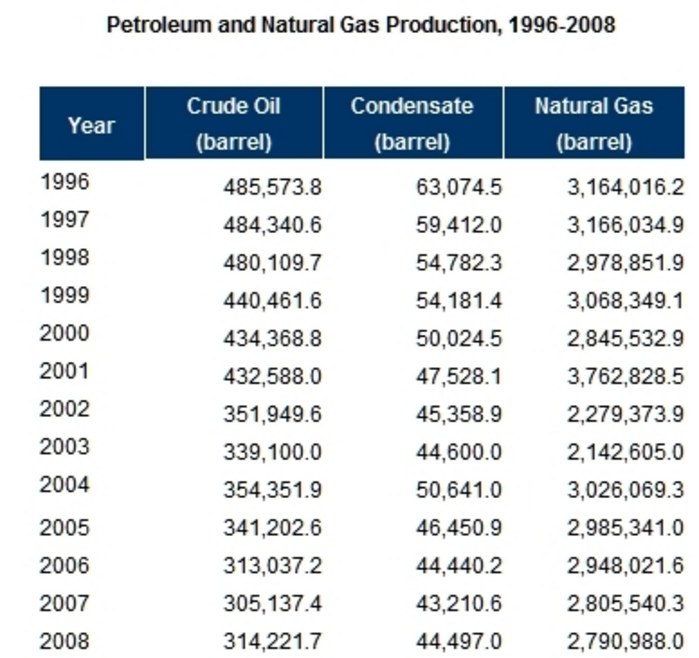

Naturally, economic and population growth exert ever greater pressure on scarce energy resources. Yet the overall health of Indonesia’s petrochemical industries has been in inexorable decline. The country’s oil industry is one of the world’s oldest, but annual crude oil production peaked in 1994 at just over 1.6 million barrels per day (bpd).[7] Since then output has declined steadily so that crude oil output fell from 1.4 million bpd in 2000 to 0.9 million bpd by 2009. Natural gas output also declined in the same period, albeit less dramatically from 2.9 to 2.5 trillion cubic feet (TCF).[8] While it remains a net exporter of energy, since 2004 Indonesia has been a net and steadily growing importer of oil. Imports of crude oil and associated petroleum products increased from 17% of Indonesia’s total imports in 2000 to around 33% by 2010. [9] Given that the Indonesian government has long provided fuel and electricity subsidies, such imports become increasingly unsustainable as Indonesia’s oil production falls at the same time that domestic demand rises.

As a result, Jakarta feels compelled to reshape gas export policy in order to improve its own energy security and investment climate. At the same time, oil and gas export revenues are not as vital to the Indonesian economy as they were in the 1970s and 1980s. Indeed, the share of the energy sector (oil, gas and mining combined) in Indonesia’s GDP has been steadily declining as energy sector investments have lagged. Oil, gas and mining currently contributes about 10% of Indonesia’s GDP, down from around 15% in 2000. Looking at Indonesia’s total exports during the same period, the share of oil and gas has fallen from 23% to around 19% of total value. Nevertheless, in the last 5 years the energy sector still contributed approximately one third of all government revenue, bolstered by high global prices and increases in coal and mining revenues.

Source: Badan Pusat Statistik Republik Indonesia (Statistics Indonesia)

The Bontang terminal is located relatively close to Java and Bali, where much of the country’s manufacturing is also concentrated. Not only is it Indonesia’s biggest LNG plant, but it is also more centrally located within the sprawling archipelago than either the ailing Arun plant in Aceh or the new Tangguh facility in Papua. Therefore, Bontang will be increasingly used to supply the domestic market whilst more remote plants such as Tangguh will still serve export markets given the higher gas prices overseas. Whilst some of the Tangguh gas will be sold domestically, Indonesia does not have a pipeline network in place capable of transporting large volumes from remote locations. Jakarta considers establishing inter-island pipelines over the long distances required to be prohibitively expensive. As Java is still dependent on expensive diesel oil to satisfy much of its power requirements, the development of LNG receiving terminals is seen as a more cost effective solution to supply its main population and industrial centres.

Whilst Indonesia’s population is the fourth highest in the world after China, India and the USA, population densities vary considerably. Java, the economic and political powerhouse of the country, houses some 58% of Indonesia’s population within only 7% of its landmass, and its six provinces have the highest population densities in the country. Smaller neighbour Bali has the highest population density of any province outside Java. These core islands also contain the lion share’s of Indonesia’s value added industries in manufacturing and services. By contrast, the outer islands account for nearly 93% of the country’s landmass but contain only around 40% of the population. However, much of Indonesia’s known resources are found in these outer islands, resulting in complex logistical challenges in delivering energy throughout the sprawling archipelago.

As a result, Indonesian state gas distributor PGN announced in March 2008 that it was planning to build three LNG receiving terminals for the Bontang and Tangguh gas. The first will be the West Java FSRU in Jakarta Bay with a capacity of around 3 MT a year. This will be followed by another terminal in East Java to supply second city Surabaya, and thereafter in Belawan, North Sumatra to service that island’s biggest city of Medan. The West Java terminal was originally expected to begin operations in 2011 but has been delayed by financial problems and technical difficulties. Golar Energy recently won the US$500 million contract for its construction, which will be the first FSRU project in East Asia. In addition, three gas transmission networks will also be established linking East Kalimantan and Java, and several cities in Java, Sumatra, Kalimantan and Sulawesi will benefit from the development of urban gas networks. These developments underline the fact that whilst Japan is still the main export market for Indonesian gas, it is increasingly having to compete with domestic buyers for supplies.

The effect of subsidies

One of the main reasons why Indonesia suffers from energy shortages is due to long-standing fuel and electricity subsidies, which raise consumption levels and encourage inefficiencies. Household consumers, especially those in the middle class, respond to artificially low prices by using more fuel and electricity than if they paying market prices, whilst businesses also have less incentive to conserve and innovate. Energy intensity data reveals that Indonesia uses more energy to produce electricity than its neighbours Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines, whilst some economists have even projected fossil fuel consumption to fall by 20% if fuel subsidies were eliminated.[10] Along with restricting gas exports, reducing subsidies is also integral to bolstering Indonesia’s energy security.

As a result of rising crude prices up to mid-2008, an increasingly large proportion of government spending has been required to sustain fuel subsidies, which are payments to Pertamina by the central government to compensate the firm for losses it experiences due to low domestic fuel prices. When oil prices reach unexpectedly high levels, subsidies consume a higher proportion of the state development budgetn. Likewise, when oil prices are underestimated, the central government risks overspending on development. The dramatic price fluctuations of recent years have thus made for a challenging policy environment for government planners.

Nevertheless, reducing fuel and electricity subsidies is still politically dangerous, with demonstrations against their removal having a history which stretches back to the 1960s. Indeed, it was their slashing at the insistence of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which triggered much of the unrest that culminated in ending President Suharto’s 33 year reign in May 1998. Subsequent attempts to phase out the subsidies also caused riots and protests as consumers feared rising living costs. Maintaining the subsidies has attracted criticism, however. Whilst fuel and electricity subsidies may be intended to help the poor, in reality the rich consume more of the subsidies since it is they who drive motorcars rather than small motorbikes and have more electrical appliances. Research commissioned by the OECD suggests that the wealthiest 40% of Indonesians benefit from 65% of fuel subsidy spending [11] whilst the Asia Development Bank (ABD) notes that “the top 10% of income earners receive 45% of the fuel subsidies and the poorest 10% less than 1%”.[12]

Furthermore, it can be argued that the current system of subsidies actually hurts the poor since less money is available for both development and welfare projects.[13] A World Bank report of 2008 put the cost of maintaining Indonesia’s total subsidies for both fuel and electricity at over US$20 billion annually – greater than total government spending on health, education, housing and public security. Whilst crude prices have fallen from a high of US$147 a barrel on July 11, 2008, the opportunity cost to Indonesia’s overall development remains significant. Based on an oil price of US$77 a barrel, the government’s 2010 budget projects that the combined cost of electricity and fuel subsidies will reach US$15.73 billion in 2010, some 13% of total government spending.[14]

Nonetheless, Jakarta realises that reducing and eventually removing the subsidies is unavoidable. In 2008 it announced that, since fuel subsidies are meant for those on low-incomes, it intends to gradually remove them for private car owners. This policy shift is due to commence in 2011 with a view to full implementation by 2014, when fuel subsidies will be restricted to public transport and motorcycles. The central government has already began reducing the electricity subsidy, which itself cost some US$6.2 billion in 2009. In June 2010, the House of Representatives (DPR) approved an Energy Ministry decree allowing state electricity utility PLN to raise rates by 15% for industrial users. Beginning in July 2010, these rates are to be increased annually as the subsidies are phased out. By 2014 all businesses and the top 5% of household consumers must pay market prices.[15] Current electricity prices in Indonesia of Rp600 (US7 cents) per kwh are around half of the unsubsidised market price.

As a result of selling electricity at far below cost, PLN posted losses of US$1.2 billion in 2008, the biggest loss of any state-owned enterprise in that year.[16] The rate hike is thus intended to stabilise the firm and to fund much-needed electricity infrastructure upgrades. The government has set itself a deadline of 2012 to add 10,000 megawatts to the power grid, a capacity increase of approximately 40%. Since a further 10,000 megawatt increase would still be needed to eliminate electricity rationing entirely, PLN is implementing a thorough overhaul of its generating capacity which requires an average investment of US$7.6 billion a year until 2018. Under the present system of subsidies, such ambitious expansion plans would be far too costly since greater output leads to ever more subsidies. [17]

New LNG projects

This section will deal with the five LNG projects being affected by Jakarta’s energy policy reforms. Japanese investors and energy buyers are closely involved in all five schemes, despite policy upheavals in Jakarta which threaten the viability of new LNG projects in Indonesia. Indeed, Japanese firms are behind moves to establish three new LNG processing plants within the next half decade. The long experience of Japanese firms operating in the archipelago, along with Indonesia’s geographic proximity and remaining untapped potential ensures that the country is still a viable investment destination. The Japan-Indonesia Economic Partnership Agreement (JIEPA) reinforces this perception given that one of Japan’s main objectives in signing was to strengthen the hand of its resource interests in Indonesia.

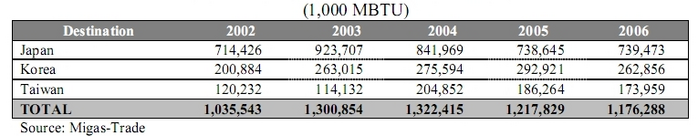

LNG production and exports [18]

LNG exports by volume

LNG exports by destination

Senoro Donggi

In resource terms, the first fruit of the JIEPA was supposed to be the Senoro Donggi LNG processing facility near the town of Luwuk in Central Sulawesi province. However, its development has been repeatedly delayed by pricing negotiations, threatened by government interference and subjected to legal challenge. Senoro Donggi, which was originally slated to become Indonesia’s fourth LNG processing plant, is now expected to come on line sometime in 2012 or 2013.

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries holds a controlling 51% stake in the project, and reportedly forged ahead after receiving export guarantees before the signing of the JIEPA in August 2007. The Japan Bank for International Cooperation (JBIC) agreed to partially finance the US$3.7 billion project, on condition that Japanese utilities Kansai Electric and Chubu Electric would each receive half of the plant’s 2 million tonne (MT) annual output for 12-15 years. In February 2009 provisional sales agreements, otherwise known as Heads of Agreement (HOA), were signed with both the Japanese utilities to supply each with 1 MT per annum over 15 years. By June 2009 the plant’s front end engineering and design (FEED) had been completed and the consortium had chosen the main contractor for the Engineer, Procure and Construct (EPC) stage of the project. The exports to Kansai and Chubu were set to commence in 2012 but the project stalled in June 2009 when Indonesia’s then Vice-President Jusuf Kalla, himself a Sulawesi native, insisted the gas be sold domestically instead, since Indonesia faced energy shortages at home. Moreover, Kalla claimed that the agreement to export all output to Chubu and Kansai contradicted legislation to prioritise domestic demand over exports. Indonesia’s Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry also rejected the contracts on the basis that the agreed sales price was too low. The contracted gas price had been set at US$3.85 per million British thermal units (MBTU), similar to prices secured by Chinese and South Korean firms for Tangguh LNG although for somewhat longer terms and bigger volumes. Despite the fact that this price would rise under the Japan Crude Cocktail index if oil prices also increased, in March 2009 Indonesian state petroleum firm Pertamina also argued that the agreed price was too far below prevailing global prices of between US$8 and US$9 per MBTU.

Throughout 2009 it appeared that the Indonesian side was trying to secure better terms from Mitsubishi and its Japanese customers, mindful of the furore surrounding its underselling of the Tangguh LNG to China and South Korea. Jakarta delayed the project again by setting six preconditions for final approval of the plant’s construction, chief among them a price increase. With the Tangguh issue having become politicised in campaigning for the July 2009 presidential elections, the administration wanted to be seen by voters to play tough with Japanese interests. As a result, it seized on a February 2009 floor-price proposal made by the Indonesian House of Representatives’ Commission VII on energy.

The Commission’s main precondition was Japanese acceptance of an absolute minimum price, determined by the Indonesian government, which would apply if crude prices fell to US$40 a barrel or under. The February 2009 provisional sale agreements did not specify any minimum price for the gas from the proposed LNG plant. As a result, it was rumoured that Chubu and Kansai might seek international arbitration to settle the case, potentially threatening the feasibility of the Senoro scheme. However, in July 2009 Evita Legowo, the Energy Ministry’s director general of oil and gas, dismissed this possibility by stating that the initial supply agreements were only provisional and that all prices have to be approved by the Ministry before they are finalised. She added that, “The government has not signed anything related to the project. The initial agreement was between the companies concerned”.[19]

Nevertheless, the possibility of Indonesia reneging on the Senoro agreement caused a diplomatic rift between the two governments that reached all the way up to the top. At first, the Japanese Ambassador Kojiro Shiojiri wrote to Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono warning of potential damage to bilateral ties if Jakarta restricted exports from Senoro. Soon after, Japanese Prime Minister Aso Taro also spoke about the issue with President Yudhoyono at the G-20 meeting in London on April 1, 2009. He reiterated Tokyo’s stance that the stability of Indonesia’s LNG supply is crucial to Japan. Despite such intense diplomatic pressure, in March 2010 Indonesian Energy and Mineral Resources Minister Darwin Zahedy Saleh backed Kalla’s stance over keeping the Senoro gas for domestic use despite Kalla no longer being Vice-President.

The Indonesian government was also insisting that the Mitsubishi-led consortium meet five other requirements to gain approval for the Senoro plant. These included selling at least 25% of the gas on the domestic market, a revision to the project’s development plan and resolution of an outstanding legal dispute between Mitsubishi and PT LNG Energi Utama. This dispute dates back to August 2008, when Jakarta-based Energi Utama sued Mitsubishi for more than US$709 million in damages. In addition to claiming it had exclusive rights to the Senoro scheme, Energi Utama also accused the Japanese firm of purloining confidential information regarding production costs, thus unfairly enabling it to win the LNG plant construction contract.

In March 2009 Energi Utama formally lodged a claim against Mitsubishi with Indonesia’s Business Competition Supervisory Commission (KPPU), which subsequently launched an investigation. Three months later, the KPPU cleared Mitsubishi of the alleged unfair business practice charges, citing a lack of evidence. Nonetheless, the body criticised state oil firm PT Pertamina and PT Medco Energi Internasional for not exercising appropriate corporate governance when choosing its partners in the scheme. It also pointed to insufficient oversight from the government and BPMigas, Indonesia’s upstream oil and gas regulator, which contributed to the dispute and the ensuing delays.

The case had appeared closed but in June 2010 the KPPU announced further investigations into Energi Utama’s allegations of collusion in the tendering process. The KPPU has again been looking into apparent violations of the Antimonopoly Act (Act No. 5/1999), specifically Article 22 concerning collusion and Article 23 regarding the use of confidential bidding information by competitors. The KPPU is additionally investigating a new allegation that Mitsubishi consortium also violated Article 19d, regarding discrimination in the business community. Mitsubishi and its local partners were summoned to hearings between July 19, 2010 and September 19, 2010, and the KPPU’s investigation was set to run until October 12, 2010. Reports in the Indonesian press suggest that irregularities in the tendering process did indeed occur. For instance, Mitsubishi won despite submitting a more costly bid than Energi Utama. Upon securing the tender, the Mitsubishi consortium subsequently doubled the cost of the required investment to complete the project.

Chubu Electric has remained committed to its HOA preliminary agreement. Japan’s third-biggest utility has had to pay a premium on the LNG short-term market in the last 12 months after an earthquake in August 2009 forced it to suspend operations at its Hamaoka nuclear power plant. However, the uncertainty surrounding the project prompted Kansai to pull out in August 2009. Conscious that Japanese customers will likely pay more for the gas than if it was sold locally, the consortium has maintained that export is the best option for both the plant’s financial viability and Indonesia’s reputation as an investment destination. In 2008, the OECD estimated that Indonesia’s domestic gas prices are at least a third less than international prices.[20] Nonetheless, Kansai’s decision prompted the two local partners Pertamina and Medco, which hold 31% and 18% respectively, to open talks with several potential domestic buyers who subsequently baulked at the asking price. Since Indonesia lacks the expertise to exploit and develop its own gas resources, and needs foreign investment to fuel its own economic growth, Mitsubishi’s role in the Senoro project is considered critical to its feasibility. Pertamina has also noted that both Mitsubishi’s participation in the scheme and the plant’s overall financial viability are predicated on its output reaching the Japanese market.

Jakarta eased the pressure somewhat when a decree was issued in September 2009 to allow firms to export gas if no domestic buyers were forthcoming. Subsequently, Japan’s Kyushu Electric and South Korea’s state-run Korea Gas (KOGAS) both signalled their interest in lifting 0.3 MT and 0.7 MT per annum respectively over a 15 year period, following Kansai’s decision not to renew its HOA for 1 MT per annum in 2009. This prompted Mitsubishi to propose US$2.5 billion of funding if they could export most of the LNG, and a compromise was announced on June 17, 2010 that the plant would have to sell only 25% of its production on the domestic market. At the same time, BPMigas chairman Raden Priyono confirmed that the project had satisfied all the regulator’s demands, and was only waiting for final approval from Vice-President Boediono, who replaced Kalla in October 2009.

Nevertheless, as of October 2010 the Senoro Donggi project was still in need of finance, with the developers canvassing both foreign and Indonesian financial institutions for investment capital. The figure of US$3.7 billion accounts for both upstream and downstream, with some US$2 billion still required to fulfill upstream commitments, namely the exploration and production of gas from the Senoro-Toili and Matindok gas blocks. The remaining US$1.7 billion is needed for downstream costs – the biggest being the actual plant construction. In September 2010, it was revealed that KOGAS, the world’s single largest corporate buyer of LNG and South Korea’s sole wholesaler, was in negotiations with Mitsubishi to acquire a 9.8% equity stake in the Senoro LNG project. [21] Mitsubishi is also hoping that the JBIC will make good on its original commitment to partially finance the project, especially now that the export issues seem resolved.

By October 2010, the project seemed to be finally falling into place. Chubu Electric has confirmed it aims to buy 1 MT per annum of LNG for about 13 years, commencing in the second half of 2014. The firm expects to sign a firm contract for the purchase in October 2010, and also intends to offload some of the Senoro LNG to third parties. Kyushu Electric, however, instead signed a HOA with the Gorgon LNG gas project in Western Australia for 0.3 MT per annum over 15 years, the same volume it was reportedly interested in acquiring from Senoro. The firm has also signed up to buy 0.7 MT per annum over 20-years from Wheatstone, another Chevron LNG project in Western Australia. Kansai Electric has recently performed a u-turn and reopened talks with Pertamina to purchase some of Senoro’s output. Nevertheless, doubts remain over the plant’s financial viability, given that the Senoro and Matindok fields’ reserves are not huge and 25% of their output must be sold domestically. Mitsubishi has yet to commit to a timeframe for its development but is under pressure from Jakarta to make a final investment decision (FID) as soon as possible. Furthermore, all export sales agreements remain preliminary and may be annulled in the event of further difficulties with the scheme. Indeed, with new LNG developments underway in Australia, Papua New Guinea and Qatar, Indonesia can ill afford to place further obstacles in the path of the Senoro project.

Sengkang

Despite such difficulties, Tokyo Gas has been in talks to join another LNG project in Sulawesi – the Sengkang scheme led by Australia’s Energy World Corp (EWC). The Japanese utility firm has been trying to acquire a 25% equity stake in each of EWC’s four wholly owned subsidiaries involved in the scheme, and has signed a HOA to buy 0.5 MT of LNG annually from Sengkang. Initial output is projected at 2 MT annually from 2012 before potentially rising to 5 MT per annum. However, in March 2010 BPMigas subsequently slammed rejected? the preliminary sales agreement with Tokyo Gas as it claims EWC has yet to apply for approval for the project from the regulator. It has even threatened to impose sanctions on EWC executives but the firm counters that copies of the project approval have been distributed to numerous government agencies and even the President himself. Despite improvements in recent years, this case illustrates that doing business in Indonesia can still be an opaque and murky process.

Indeed, this is not the first time that EWC and BPMigas have clashed over the Sengkang LNG plant. In January 2010, the regulator rejected plans for the plant as being incomplete. Specifically, BPMigas Chairman Raden Priyono charged that, “The plan of development is not backed up with valid data. How can we approve the plan of development if we don’t even know the reserve data? It’s strange they want to drill without an initial seismic survey.” EWC argued that a full 3D seismic survey would be overly expensive for such a marginal field as the Sengkang Block, and proposed a mini-seismic survey instead.[22]

The Sengkang project is scheduled to take less time to complete than other LNG processing plants as it will be tapping gas from an already active field, whose output is presently used to fuel the gas-fired Sengkang Power Plant operated by EWC subsidiary PT Energi Sengkang. The Sengkang Block is estimated to contain some 2-4 trillion cubic feet (TCF) of recoverable gas, whilst a further 300-500 billion cubic feet (BCF) of gas is apparently available for the US$500 million LNG plant.

In keeping with Indonesian government policy, it is also thought that much of the production will serve the domestic market. This could be the reason for the regulator’s criticism of any the preliminary sales agreement with Tokyo Gas. EWC does intend to export an unspecified ‘small percentage’ of the LNG in order to increase the facility’s financial viability although it remains to be seen if Tokyo Gas will indeed secure 0.5 MT of LNG annually. However, any delays in the plant’s development will likewise delay LNG supplies to state-owned gas distributor PT Perusahaan Gas Negara (PGN). EWC reportedly signed a preliminary agreement in September 2009 to sell between 1.5 and 5 MT of LNG annually over five years to PGN’s proposed regasification terminals in Java and North Sumatra. EWC has also secured a take-or-pay supply contract with state electricity firm PT Perusahaan Listrik Negara (PLN) until 2022. Since the Sengkang plant is located closer to Indonesia’s major population centres than any other LNG facility, it is unlikely that much more than 0.5 MT of LNG per annum would be available for export to Japan.

Abadi

Whilst other Japanese firms have been facing difficulties in Indonesia, Inpex has been consolidating its position as one of the major foreign resource firms operating in the archipelago. In September 2009, the company received formal approval from BPMigas to construct an offshore LNG plant to process gas from the Abadi gas field in the Timor Sea’s Masela block. Inpex puts estimated construction cost at around US$10 billion, significantly higher than Indonesia’s other new facilities in Papua and Sulawesi. Indeed, a degree of controversy has followed this plant, too. News reports surfaced in August 2009, just prior to the final approval announcement, that PT Tiara Energy, along with partners Flex LNG and Samsung, were offering to build the Abadi floating LNG plant for a cost of around US$4.5 billion.

Inpex holds a 100% stake in the Abadi field, and had been assessing what kind of processing plant to build after deciding not to process the gas in nearby Australia. BPMigas has pushed strongly for Inpex to build a floating LNG facility in Indonesia, arguing it is both more efficient and economical, and thus could be completed sooner. This is probably due to the field’s remote location, around 200 kilometers south of Saumlaki island in eastern Maluku province. The facility will be Indonesia’s first such offshore plant and is expected to come on stream in 2016. Such floating LNG facilities are seen as increasingly attractive by energy firms looking to exploit remote gas fields, since processing the gas into LNG is conducted offshore on large ships, instead of being piped to an onshore processing plant.

As with the exploitation of unconventional gas, Indonesia sees itself in a race with Australia to develop floating LNG plants. Royal Dutch Shell’s Prelude gas field, some 475km north-northeast of Broome in Western Australia, could become the world’s first floating LNG facility if it begins production on schedule in 2016. If Inpex can start production from the Abadi field before Prelude comes online, it could be a huge boost both for the firm and for the Indonesian oil and gas industry as a whole. However, the Abadi project cannot afford many controversial delays since as many as seven floating LNG projects could be under development or in production in northern Australia within the next decade. If the Abadi development goes awry, as with the Senoro plant in Sulawesi, then Australian LNG will become increasingly attractive to Asian firms. Likewise, foreign firms looking to tap other Indonesian gas deposits near the border with Australia might view processing the gas at an Australian floating LNG plant as a more attractive option than doing so in Indonesia. This risk is potentially significant given the profusion of smaller, so called ‘stranded’ natural gas deposits which are thought to exist in the Timor Sea between Indonesia, East Timor and northern Australia.

The proposed Abadi floating LNG plant.

Inpex estimates the Abadi field contains more than 10 TCF of gas reserves, which would make it Indonesia’s second-biggest new gas field after Tangguh in Papua province, which has combined reserves of 14.4 TCF. The firm expects annual production to reach around 4.5 MT per annum under its approved plan of development but Indonesia’s former Energy and Mineral Resources Minister Purnomo Yusgiantoro has stated that the estimated field reserves may actually yield up to 9 MT of LNG per year. Inpex intends to export the bulk of the LNG to Japan, although it will have to sell at least 25% of it on the domestic market. On this key issue BPMigas remains coy, and in August 2010 agency spokesman Elan Biantoro would only say, “Some of the LNG will be exported and some for the domestic market”. [23] Given the struggles which Japanese firms are experiencing over the Senoro and Sengkang LNG exports, it is seems likely that the Abadi field also faces an uncertain future. The plant’s huge construction costs mean that financial viability will only be guaranteed if the bulk of its LNG can be exported. However, unlike the centrally located Sulawesi LNG plants, Abadi’s remote location means its output is more attractive for export.

Whilst Inpex remains the sole operator of the Abadi field at present, Indonesian state oil and gas concern Pertamina has been eyeing a 30% participating stake in the project. As Indonesia lacks the expertise to tap its own natural gas reserves, it has become standard practice for Pertamina to piggyback on foreign-developed projects in the archipelago as it seeks to increase its gas reserves and production. Although Inpex is 30% owned by the Japanese government, in February 2009 it emerged that the firm was facing a liquidity shortage due to the global financial crisis, with Royal Dutch Shell also looking to buy into the Abadi project. It now appears that Inpex is instead raising additional investment capital by issuing new shares, although it might sell part of its 76% stake in the Ichthys LNG project near Darwin in Australia. Nonetheless, it is thought that Inpex’s lack of experience in developing floating LNG technology will force it to partner with another foreign firm such as Shell with a recent track record of innovative LNG development. However, the Anglo Dutch firm is heavily committed to developing its own floating LNG technology in Australia, where no concerns over export allocations exist.[24]

Inpex originally signed a 30-year agreement to develop the Abadi field back in 1998 but made little progress on the scheme until Jakarta issued an ultimatum in January 2008, ordering the firm to submit a firm development plan or lose its contract. It duly submitted one in June 2008. Now that formal approval has been secured, the Indonesian government is pushing for plant construction to begin in 2011 as it competes with Australia to open the world’s first floating LNG processing facility.

The Masela block is around 350km north of Darwin, Australia in water depths of 400m to 700m.

Tangguh

Meanwhile, a long delayed project that has finally come to fruition is the Tangguh LNG plant in West Papua province, operated by multinational BP. Soon after it started production in May 2009 both of its processing units, or trains, were shut down as then BP chief executive Tony Hayward revealed that the firm had intentionally delayed operations due to low global LNG prices. Aware that Jakarta would be unhappy about such delays, local management distanced themselves from Haywood’s remarks and blamed the shutdowns on technical issues instead. The result is that Tangguh shipped only 16 LNG cargoes in 2009, well under its original target of 56, although the plant is presently on target to deliver 116 cargoes in 2010. Of these, 28 are set for China’s Fujian province, 24 for South Korea, 55 for Sempra Energy’s new receiving terminal in Mexico and nine to Chubu Electric Power in Japan. BP Indonesia owns 37% of the project with its major partners being Japan’s Mitsubishi, Nippon Oil and Sumitomo along with the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), and the plant has a processing capacity of 7.6 MT per annum.

The Tangguh project has also been controversial as critics have attacked the low prices secured by Chinese and Korean buyers as a case of gross underselling. Customers were initially hard to find for the Tangguh LNG but BP eventually signed a 25-year contract to sell 2.6 MT per year to fellow shareholder CNOOC in 2002, in addition to 20-year purchase agreements with Korean firms POSCO and K-Power to supply 1.15 MT per annum signed in 2004. Rising world commodity prices thereafter prompted some Indonesian lawmakers to argue that these contracts even undercut domestic gas prices. Whilst the original contracts with CNOOC, POSCO and K-Power were subsequently revised upwards, with a closer tie to world crude prices, volatile global energy prices and a glut of LNG on the market in the Asia-Pacific made these pricing negotiations drawn out and complicated. When oil prices were inching towards US$140 a barrel, Jakarta even threatened to renege on these sales agreements unless the buyers agreed to pay more, although this could be viewed as verbal sparring prior to the 2009 legislative and presidential elections. Nevertheless, the spike in oil prices before the global financial crisis prompted some Indonesian politicians to suggest the country should receive greater economic benefits from its oil and gas exports.

In November 2009 it emerged that Chubu Electric was in advanced negotiations to secure 18 cargoes of the Tangguh LNG, equal to 0.5 MT a year for three years. Whilst no pricing specifics were revealed, BPMigas chairman Priyono claimed the buyer proposed quite a high price. Given the controversy over the original supply contracts, these comments suggest that Chubu will be paying substantially more per cargo than CNOOC, POSCO and K-Power, who finally agreed to pay around US$3.8 per MBTU. The Chubu gas will be diverted from a flexible contract to supply 3.7 MT of LNG annually to American firm Sempra Energy, who have the right to divert half of this volume elsewhere. BPMigas also announced in June 2010 that Tangguh will supply 0.5 to 0.7 MT of LNG per annum to the new receiving terminal near Jakarta, due for completion in 2012. The regulator was quick to stress that, as with the Chubu contract, this LNG will be part of Sempra’s diversion volume and will not affect exports.[25]

Despite the plant’s remote location, the central government has earmarked some of Tangguh’s future production for the domestic market. The facility presently has two LNG processing trains in operation, with a third train under consideration. Jakarta is adamant that output from this proposed third train will serve the domestic market. KOGAS has been interested in developing this third train, but has been deterred by Jakarta’s reluctance to provide export guarantees. As with Senoro Donggi, such a stance affects the viability of new LNG developments in Indonesia.

Bontang

Whilst several new LNG projects are in various phases of development, Bontang remains the jewel in the crown of Indonesia’s oil and gas industry. The facility currently has eight trains with a total processing capacity of around 22.5 MT per annum. Bontang, 15% owned by the Japan Indonesia LNG Co (JILCO), has been one of the world’s most prolific LNG facilities since it opened in 1977 under supply contracts with Japanese utilities.[26] Indeed, Bontang LNG has enabled East Kalimantan to post the highest Gross Regional Domestic Product (GRDP) figures of any Indonesian province.[27] Even as gas reserves around Indonesia’s other LNG plant in Aceh province dwindled, upgrades to Bontang allowed the country to consolidate its position as the world’s largest LNG exporter until Qatar displaced it in 2006. The plant’s output did subsequently increase to 24.59 MT per annum in 2004, but fell off soon after when its gas fields suffered production problems. As a result, Jakarta requested that Japanese buyers cancel 41 LNG cargoes set for delivery in 2005 and clearly signalled that Indonesia’s world leading LNG industry was in trouble. This was repeated in 2007 when the government failed to deliver some 72 cargoes to foreign buyers, mainly those in Japan. [28] Such difficulties fulfilling contracted export requirements presented Jakarta with further motivation to reduce Bontang’s LNG exports to Japan.

Bontang is presently the source of around 90% of Japan’s LNG imports from Indonesia Under long-term contracts with Japan’s Kansai Electric Power, Chubu Electric, Kyushu Electric, Osaka Gas, Toho Gas and Nippon Steel, the plant has been exporting around 12 MT annually to the island nation. Up to early 2010, approximately 230 MT of LNG has been exported from Bontang to Japan, South Korea and Taiwan, most of it to Japan. However, LNG exports to Japan from this plant in East Kalimantan province will end in 2020.Whilst it still has the ability to supply Japan with around 10-12 MT a year, export volumes to Japan are being dramatically reduced in order to service Indonesia’s domestic market. Contracts to supply Japan with 8.4 MT per annum expire at the end of 2010 and similar deals to sell a further 3.6 MT conclude in 2011. Even though such contracts typically run for 15 to 25 year periods, they will be renewed for only 10 years, with 3 MT annually until 2015 and thereafter 2 MT per annum until 2020. Highlighting the poor management of the industry, however, in May 2010 Indonesian Energy and Mineral Resources Minister Darwin Zahedy Saleh suggested that these smaller export contracts could be further revised downwards in order to supply the domestic market. Ironically, it has since emerged that Indonesia will have a considerable oversupply of LNG in 2011 as a result of restricting exports from Bontang, largely due to delays in establishing the West Java FSRU. For investors and customers seeking continuity and stability in Indonesia’s oil and gas industry such uncertainty is a major concern, especially since developing LNG processing facilities is a very lengthy and costly process.

Whilst the LNG market is generally more stable than crude, since around 85% of global supply is sold under multiyear contracts, and it was reported in March 2009 that buyers in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan might divert up to 12 cargoes of contracted Indonesian LNG to other markets in Asia or Europe. However, by August 2010 the effects of the global downtown had dissipated to the extent that both South Korea and China almost doubled their LNG imports compared to the previous August, whilst Japan too reported increased import volumes. In the short-term, this rebound in the regional LNG trade will benefit Indonesia. The floating receiving terminal to be constructed near Jakarta will receive 1.5 MT a year from Bontang once it becomes operational in 2012 but BPMigas estimates that Indonesia will have 68 excess cargoes of LNG in 2011, mostly from Bontang. The terminal had been due to commence operations in 2011 but has been delayed to at least December 2011, hence the glut of 68 cargoes. The regulator has stated that approximately 20 of them will be sold on the spot market, depending on domestic demand. At prevailing prices, each cargo is worth around US$30-65 million on this short-term market. BPMigas has also been marketing this excess in Japan, China, Taiwan, South Korea and Thailand. Osaka Gas, Kansai Electric and South Korea’s KOGAS are apparently among the interested parties as their long-term contracted supplies from Bontang are reduced. This extra gas has also been offered to Singapore’s new US$1 billion LNG receiving terminal, due to open in early 2013 with an initial capacity of 3.5 MT per annum. Any such deal would augment Indonesia’s existing long-term supply deal with the city state. Further highlighting the lack of clarity and coordination that characterises Indonesian gas export policy however, this decision followed statements the previous month that Indonesia was looking to reduce gas export volumes to Singapore in order to better supply its domestic market. [29]

As a result of Indonesia’s plans to reduce exports, Japan is anxious to diversify its LNG supply base. In September 2010 Nakanishi Kohei, managing director of state-backed JBIC, said that from 2011 the country is considering increasing its LNG imports from Russia’s Sakhalin-2 project, which began exporting in 2009. Russia presently supplies 4.3% of Japan’s overall LNG imports, compared to Indonesia’s 20% share. Over half of LNG output from Sakhalin-2 will be sold to Japanese buyers under long-term contracts. Nakanishi elaborated that Sakhalin is the most natural and convenient oil and gas source for Japan given that, “The distance between Sakhalin and Japan is one-sixth of the distance between Japan and the Middle East and nearly half the distance to Indonesia. This means we can offer our clients a better price due to lower transportation costs.” [30]

Since Japan is the world’s biggest buyer, accounting for around 30% of global LNG demand, such moves indicate that a major realignment is underway in the sector. Indonesia’s decision to restrict exports comes at a time when more LNG projects are set to come online worldwide, especially in its southern neighbour Australia. Indonesia has been the biggest supplier of LNG to Japan since the late 1970s, but has recently been overtaken by both Malaysia and Australia, who exported 6.88 MT and 6.33 MT of LNG respectively to Japan in the first six months of 2010, compared to Indonesia’s 6.30 MT. [31] Australia has a raft of LNG projects under development, from which Japan, South Korea, China and India have all made commitments to buy upon completion. Given that Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei have less scope to boost export output, these new projects in Australia will likely mean that the southern giant will increasingly dominate the Asian LNG trade. In 2011, Woodside Petroleum’s new Pluto processing plant in Western Australia is scheduled to commence exports of 2 MT per annum to Kansai Electric Power and 1.75 MT annually to Tokyo Electric Power. The Gorgon and Wheatstone projects, both led by Chevron, will follow thereafter, with deliveries to Japan possibly starting in 2014. Australia’s LNG exports to Japan are projected to reach 29 MT per annum by 2017, more than double present volumes.

Indonesia presently has three LNG plants in operation.[32]

Unconventional gas

The issue of natural gas is central to government development planning. During the Suharto era (1966-1998) oil and gas export revenues were used to finance agricultural and industrial development, particularly greater rice production. With little surplus from oil nowadays, LNG export earnings assume greater importance for government budgets. Whilst Indonesia has a dilemma over how to balance its domestic energy requirements with earning export revenues, a quiet revolution in energy development could assist government planners. In recent years American energy firms have been pioneering the exploitation of coalbed methane (CBM) and shale gas, and unconventional gas techniques and technology are now appearing outside of North America. It is thought that unconventional gas deposits might exist throughout the Asia-Pacific, and several schemes have already been proposed in Australia and Indonesia.[33] Indeed, Indonesia has been aggressively scouring for unconventional gas reserves like CBM and shale gas in order to boost its fragile energy security.

The archipelago is thought to possess significant CBM reserves of approximately 453.3 TCF across some 11 different locations. It is estimated that up to 112.47 TCF might be classified as proven reserves with some 57.60 TCF viewed as potential reserves. For CBM exploration and production, the potentially high yield basins are in South Sumatra (183 TCF); Barito in southeastern Kalimantan (101.6 TCF); Kutai in East Kalimantan near the Bontang LNG plant (89.4 TCF); and central Sumatra (52.5 TCF). Others are located in North Tarakan in northeast Kalimantan near a disputed boundary with Malaysia (17.5 TCF); Berau also in East Kalimantan (8.4 TCF); Bengkulu in Sumatra (3.6 TCF); Pasir Asam-Asam also in southeastern Kalimantan (3.0 TCF); southwestern Sulawesi (2 TCF); Jatibarang in northwestern Java (0.8 TCF); and Ombilin in West Sumatra (0.5 TCF). However, extracting gas from unconventional sources necessitates taking environmental risks since the rocks containing the gas must be made more permeable. Whilst most of Indonesia’s known deposits are not located in heavily populated areas, unconventional gas has the potential to wreak tragic environmental consequences nearby. As the Lapindo mudflow disaster in Java has demonstrated, Indonesia has a poor recent record in this area, especially when well-connected domestic capital is involved, and environmentalists will be concerned by plans to tap unconventional gas in the archipelago.

Source: Hari Karyuliarto, Head of LNG Business of Pertamina, December 8, 2009, presentation at International Petroleum Technology Conference, Doha, Qatar

In its bid to pioneer the Asian CBM sector, as it did the LNG industry, the Indonesian central government has so far awarded some 20 CBM contracts, and Jakarta hopes some of these blocks will begin production as early as 2011. It has also set a target of producing LNG from CBM before 2014 which, if successful, would make it the first country to produce LNG from methane. The Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry is confident that the required infrastructure will be in place by then since it maintains that CBM can be processed into LNG at the existing Bontang LNG plant. Evita Legowo, the Ministry’s director general for oil and gas, has been quoted on the Ministry’s official website as saying, “Australia is aiming to produce LNG from CBM by 2014. If we want to be the pioneer, we must beat them to the punch.” [34] The Ministry states that CBM LNG will be used to supply the Indonesian domestic market but that electricity production from CBM will take priority over LNG processing. Any excess CBM production will thereafter be converted into LNG although it is unclear whether any of this excess will be exported.

CBM production is still a cutting edge field of exploration and development. As with conventional gas, foreign oil and gas firms will have to spearhead any innovative gas projects within the archipelago. It remains unclear as to whether the requirement to prioritise the domestic market will also be enforced in unconventional gas, however. Compromises on export allocations will have to be made if foreign developers are to help Indonesia boost its gas output. Among the other potential players, China is also aggressively searching for homegrown unconventional gas sources as its LNG imports rise sharply. Faced with soaring demand and pressure for a cleaner energy makeup, the Chinese government is aiming to increase the share of natural gas in the country’s primary energy supply from 4% at present to 10% by 2020. Indeed, Beijing officials recently estimated that China might quadruple its imports of LNG by the end of 2015. As a result, Beijing has been signing deals with Western petroleum majors to tap unconventional gas resources and industry analysts Wood Mackenzie predict that this new avenue could supply over 25% of China’s overall gas demand by 2030. [35]

Analysts are still unsure as to what effect unconventional gas will have on the global LNG market. However, it seems likely that countries with large domestic sources of unconventional gas, such as the United States, will acquire less LNG from abroad, thus influencing global LNG prices. It is also thought that Chinese domestic coal-seam and shale-gas production, in tandem with a proposed pipeline from Russia, could reduce Chinese LNG demand and threaten the feasibility of new LNG developments in the Asia-Pacific. Some industry analysts, such as Franks Harris of Wood Mackenzie, see unconventional LNG reaching only 5% of total global LNG supply by 2020. More generally, Harris also sees unconventional gas accounting for some 15% of total global gas supply by 2020. [36]

Investment climate

To fully realise Indonesia’s ambitious LNG development plans requires large-scale foreign investment since domestic energy firms do not have the capacity to lead such technically demanding projects. This section will consider some of the issues which concern foreign energy investors, many of which also affect both foreign and domestic investment generally and the wider economy as a whole.

In the decade before the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997-98, Indonesia benefitted from large foreign investment inflows which fuelled GDP growth approaching 10% per annum. Much of this came from Japanese firms fleeing the rise of the yen by moving lower tier manufacturing operations to Indonesia, with its lower labour and other production costs. The archipelago has struggled to attract similar levels of foreign investment since 1997, however. Political instability was an issue in the early post-Suharto years but the archipelago has remained largely stable since 2001. Even though Yudhoyono has twice won the presidency on promises of clean government and policy reform, little progress has been made on issues that affect foreign investment and debate still rages in Indonesia over the efficacy of neo-liberal economic orthodoxy.[37]

The difficulties frequently cited by foreign investors in Indonesia include: opaque bureaucracy, vague legislation, a weak legal system and widespread corruption; all of which feed high levels of policy uncertainty. Indonesia’s creaking industrial infrastructure is a further deterrent for manufacturing investment. However, all of these factors also existed to a greater or lesser degree during the Suharto era but did not seemingly deter foreign investment. In particular, Indonesia suffers from insufficient investment in its energy sector to satisfy burgeoning domestic demand and attract investors into value added industries. To some extent, Indonesia is caught in a vicious circle whereby it requires substantial foreign investment to upgrade its industrial infrastructure but foreign investment demands better industrial infrastructure before committing to Indonesia.

Whilst Jakarta has made some moves since 1998 towards reforming its energy sector, recent research suggests that some of these reforms have actually heightened the sense of risk for foreign investors in this sector. For instance, upstream oil and gas regulator BPMigas is seen by foreign oil and gas investors as woefully understaffed with only 367 staff overseeing an industry which attracted US$10.9 billion of investment in 2009.[38] As a result, “the way BPMigas chooses to discharge its duty to supervise and control the operation of production-sharing contractors has the effect of severely delaying and impairing the development of Indonesia’s hydrocarbon resources”.[39] Thus, whilst the country’s resources remain attractive to foreign extraction firms, as demonstrated by the number of new production-sharing contracts (PSCs) sealed each year, the amount of actual realised development is seriously hampered by insufficient inducements. This is exacerbated by the dramatic price volatility of petroleum in recent years, which makes future returns more difficult to gauge and decisions where to place limited investment capital more challenging.

Compounding these failures is a perceived lack of understanding of the industry among policy makers, members of parliament and their support staff. The same research indicates that among this cohort the prevailing attitude is that it is better to wait and conduct negotiations with extraction firms from a position of strength rather than ‘undersell’ Indonesian resources. Given the market volatility of the past decade, judging the best time for such negotiations is more of an art than a science, however. Moreover, the long gestation periods for LNG schemes also work against such thinking, as demonstrated by the furore surrounding the Tangguh LNG sales contracts with China and South Korea. Related to this view is the feeling that Indonesia today is in much better shape than in 1967 when Suharto first opened up the country to foreign resource investment in a desperate bid to improve the country’s parlous fiscal position. Consequently, policy makers are not as anxious to attract foreign oil and gas majors as in previous decades.[40]

A glimpse behind the curtain of such thinking was seen in April 2010 when legislators were considering amending the Oil and Gas Law to give Pertamina first option to take over any oil or gas fields whose PSCs were coming to an end.[41] Some Indonesian policy makers want to redress foreign dominance of the country’s oil and gas sector, and such a move would undoubtedly strengthen Pertamina’s position relative to foreign firms. However, the reality is that Indonesia has a surfeit of capital, technology and expertise when compared to these foreign operators and risks damaging this vital sector by alienating foreign investors. From the perspective of foreign oil and gas firms, Indonesia’s management of this industry is wracked by complacency, inconsistency and even incompetence, fuelled by the long years when Indonesia dominated Asia’s oil and gas sector.

Another common criticism from foreign investors in the sector is the lack of clarity in Indonesian oil and gas legislation. This ambiguity is seen to be deliberately fostered to allow officials scope to take advantage of loopholes for personal gain.[42] Furthermore, those in the industry charge that even well-drafted laws can be bypassed by presidential and ministerial decrees, in essence changing the terms and conditions of contracts after their signing. More seriously, foreign developers complain that there is inadequate recognition in Indonesia that the process of finding and extracting fossil fuels is becoming progressively more difficult and costly due to the fact that the most easily accessible reserves have already been depleted. At the same time, these firms also perceive a deteriorating operating environment, in terms of regulations and the profitability of PSCs.[43] With the Indonesian crude oil industry in seemingly irreversible decline and a stream of new LNG projects under development among its neighbours, foreign oil and gas firms are hoping that Indonesian policy makers will take these factors into greater account when trying to boost domestic energy security.

Many of these concerns are replicated across the economy and are reflected in the World Bank’s Doing Business 2010 report, which placed Indonesia 122nd out of 183 economies surveyed for overall ‘ease of doing business’.[44] Whilst Indonesia ranked a reasonable 41st at ‘protecting investors’, it managed only 146th at ‘enforcing contracts’. Oil and gas developments are invariably large-scale and long-term investments whose viability is under the greatest threat from an inadequate legal system which does not provide a reliable and impartial system of dispute resolution. Indeed, several oil and gas majors directly attribute the decline in Indonesia’s oil production to insufficient legal protection of their investments. More generally, such uncertainty makes large-scale and long-term investments less attractive relative to short-term investments designed for quick returns. Such large-scale and long-term investments are essential for Indonesia’s energy security; thus legal uncertainty deters new development and negatively impacts the economy as a whole. Another familiar complaint among foreign companies in Indonesia is the difficulty involved in establishing new ventures, especially when compared to neighbours such as Singapore, Malaysia and Thailand. The World Bank ranked Indonesia only 161st in this category in its Doing Business 2010 report.[45] Many foreign startups in Indonesia see themselves as instant targets for official harassment from immigration, police and labour officials. Indeed, foreign firms operating in the archipelago have long voiced concerns that whilst their compliance with every single rule is regularly tested, local companies are not subject to the same strictures.

Counter-intuitively, even anti-corruption drives are perceived to have damaged the investment climate in Indonesia with the bureaucracy becoming much more circumspect in supporting new initiatives. In reformasi-era Indonesia, civil servants risk being accused of corruption if their decisions eventually become more expensive than projected, even if they were made with the best of intentions. Along with many other laws in Indonesia, the definition of corruption remains vague and open to a wide variety of interpretations. As a result, decision making takes place much more slowly than in the Suharto period, and this lethargy affects many sectors of the economy, not just the oil and gas industry.[46]

Another cornerstone of political reform in Indonesia has been devolution. During the last decade, Jakarta has reversed Suharto’s policy of concentrating political power in the capital by pursuing a radical decentralisation policy which has granted much greater powers to over 400 local district governments. Under Law 25 of 1999, 15.5% of oil and 30.5% of gas revenues are now meant to remain within their province of origin. This legislation was enacted during a period of violent conflict in various provinces which prompted many to fear the breakup of Indonesia itself. In particular, separatist demands were heard in the resource rich provinces of Aceh, Papua and Riau, although in Riau these demands were not particularly vociferous and were not considered a genuine threat to the central government. Giving local governments a better deal was seen as a way to keep them within the Republic and not join East Timor in seceding. However, whilst it may have served to forestall the disintegration of Indonesia, these changes have resulted in a more complex environment for foreign operations within the archipelago. Unlike in the Suharto years, when all major decisions were made in Jakarta, foreign firms now also have to deal with local governments, which often have different priorities to the centre. Moreover, additional layers of government often mean increased opportunities for rent seeking by a larger cohort of stakeholders, and each new piece of new legislation provides further avenues for such behaviour.[47] Compounding matters, these newly empowered local officials usually have less experience in dealing with natural resource issues than their colleagues in the central government. The result is a proliferation of government decision makers, further policy uncertainty and, in some cases, additional taxes and fees not specified in the original PSCs.[48]

It seems that a battle is now playing out between those in government who are trying to improve Indonesia’s investment climate and others who seek to profit from their position as gatekeepers. For instance, Evita Legowo, the Energy Ministry’s director general of oil and gas, has publicly expressed her concern over local government corruption in approving energy and mining projects. Meanwhile, Gita Wirjawan, Chairman of Indonesia’s Investment Coordinating Board, has detailed his agency’s increasingly interventionist attempts to promote investment by pressuring the Indonesian bureaucracy to speed up the approvals process.[49] Throughout much of Indonesia, the civil service offers unrivalled employment opportunities so that potential investors increasingly have to run the gauntlet of stakeholders eager to ride the bureaucratic gravy train.[50] Indeed, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) estimates that 48 new local government units in Indonesia are using some 70% of their budget just to pay civil servants’ salaries.[51]

Conclusion

The issue of natural gas is central to government development planning. Restricting gas exports is part of a comprehensive refashioning of energy policy, triggered by a nexus of declining oil production, increasing domestic energy demand and unsustainable reliance on costly oil imports. The expiry of long-term sales contracts with Japanese utilities will enable Indonesia to begin replacing costly oil with gas-fired power generation. However, Indonesia faces a dilemma. Longer-term domestic energy security dictates that the country reverse declining gas production from its ageing fields by promoting the exploration and development of new gas finds. Since this task will fall to foreign extraction firms, compromises on export allocations will have to be made as serving the Indonesian domestic market is not sufficiently lucrative. This logic dictates that Jakarta should allow gas in more remote locations such as Papua and Maluku to be mostly exported to Northeast Asia, whilst retaining output more centrally produced in Kalimantan and Sulawesi for the domestic market.

In order to attract foreign investment, Indonesia also has to improve its investment climate. Equitable cost-recovery rules and the regulatory environment are a source of concern for many foreign oil and gas firms, whilst Indonesia’s creaking industrial infrastructure hampers its manufacturing sector. As investment in infrastructure has lagged, so has investment throughout the economy. Thus, Indonesia is caught in a vicious circle whereby it requires substantial foreign investment to upgrade its industrial infrastructure but foreign investment demands better industrial infrastructure before committing to Indonesia. The answer is to deal with bureaucracy, corruption, legal issues and policy uncertainty first. Thus, President Yudhoyono needs to show greater commitment to tackle these issues, for the good of the Indonesian economy as a whole.

The country’s gas exports act as a shop window to attract investment across all industries. In particular, the country sees itself in competition with neighbour Australia to innovate both floating LNG plants and unconventional gas. If successful, this could give the whole oil and gas industry in Indonesia a significant boost. However, high levels of policy and legal uncertainty continue to frustrate investors and hampers consolidation of this sector. Much improved energy sector governance is needed to encourage large new investments, especially since LNG developments in Indonesia could be competing with more than 12 proposed LNG projects in Australia and Papua New Guinea. In Australia alone some 140 MT per annum of new LNG capacity could become available in the coming decade. Qatar, now the world’s biggest exporter, is also looking to increase its LNG exports. Therefore, a greater awareness of the external environment might be needed if Indonesia is to improve its domestic energy security and boost export revenue from its gas fields. For Japan, Indonesian LNG remains attractive because of its geographic proximity but new developments in Australia and Papua New Guinea also threaten this perception.

One of the key motivations for Tokyo signing the JIEPA was to secure access to Indonesian mineral resources, particularly gas. Whilst significant Japanese investment in new LNG projects has since followed, their viability has been threatened by political interference which illustrates the difficulties of doing business in Indonesia. Given the controversy surrounding both the Senoro and Sengkang LNG schemes, it seems likely that the Abadi development also faces an uncertain future. The plant’s huge construction costs mean that its financial viability will only be guaranteed if the bulk of its LNG can be exported. Unlike the centrally located Senoro and Sengkang LNG projects though, Abadi’s remote location means its output should be more attractive for export. However, if the Abadi scheme goes awry, then Australian LNG will become increasingly attractive to Asian investors. Likewise, foreign firms looking to tap other Indonesian gas deposits in the Timor Sea might view processing the gas at an Australian floating LNG plant as a more attractive option than doing so in Indonesia. In order to be prevent this scenario, Jakarta has to clean up the approvals process, improve the general investment climate and show greater flexibility regarding its gas export policy. Complicating matters, Japan is Indonesia’s biggest bilateral lender and Jakarta is aware that any such export deals transcend mere business considerations.

David Adam Stott is an associate professor at the University of Kitakyushu, Japan and an Asia-Pacific Journal associate. His work centers on the political economy of conflict in Southeast Asia, Japan’s relations with the region, and natural resource issues in the Asia-Pacific. From April 2010 he is on research leave at the University of Adelaide. He wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal.

Recommended citation: David Adam Stott, “Snakes and Ladders for Japan in Indonesia’s Energy Puzzle,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 47-1-10, November 22, 2010.

Notes

[1] International Energy Agency (IEA) (2008), Energy Policy Review of Indonesia, OECD Publishing.

[2] Japanese loans to Indonesia have been channelled directly through Japanese donor agencies, and indirectly through the Asian Development Bank and the International Monetary Fund.

[3] John Riady, ‘Cutting Off Indonesia’s Coming Energy Crisis’, Jakarta Globe, July 21, 2010.

[4] Novia D. Rulistia, ‘Japanese firms lodge protest over blackouts’, Jakarta Post, July 9, 2008.

[5] Arghea Desafti Hapsari, ‘Census may indicate population boom,’ Jakarta Post, August 19, 2010.

[6] Such figures remind Indonesians that one of Suharto’s major achievements was reducing population growth from an annual average of 2.31% to 1.49% during his 33 years in power.

[7] IEA (2008).

[8] Ministry of Energy and Mineral Resources, Data Warehouse.

[9] Hanan Nugroho, ‘Energy and economic growth’, Jakarta Post, July 15, 2010.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Luiz de Mello (2008), ‘Indonesia: Growth Performance and Policy Challenges’, OECD Economics Department Working Papers No. 637.

[12] Jorn Brommelhorster, ‘Asian Development Outlook 2008 Update’, Asia Development Bank, 2008.

[13] Those living in more remote regions of Indonesia do not enjoy the same benefits of the fuel subsidy as those living in the core islands of Java and Bali. As the subsidy is dispensed at fuel depots to the distributors, who then add the cost of transportation to the outer islands, residents of more remote areas inevitably pay much higher prices than those living in the centre. The reluctance of the central government to adjust the subsidies to reflect this reality is due to the fact that export-oriented manufacturing and related higher-value services are largely concentrated on Java and Bali, along with around 60% of the population.

[14] Reva Sasistiya & Yessar Rossendar, ‘Indonesia to End Energy Subsidies by 2014’, Jakarta Globe, March 22, 2010.

[15] Only business customers and residential customers who had a power subscribing capacity of more than 900 volt amperes would be subject to the planned hikes between 2011 and 2014. According to PLN data, only 5.1% of its customers fit into this category. Camelia Pasandaran, Faisal Maliki Baskoro, Arti Ekawati & Dion Bisara, ‘Indonesian Government Puts Cap On Electricity Rate Hike’, Jakarta Globe, July 20, 2010.

[16] Riady (2010).

[17] Indonesia placed 111th in the 2009 Human Development Index (HDI), compiled annually by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) which combines health, income and education statistics to rank 182 countries for whom sufficient data is available. Neighbours Malaysia, Thailand and the Philippines were listed 66, 87 and 105 respectively.

[18] Tables taken from US Embassy Jakarta (2008), Petroleum Report Indonesia 2008.