Japan’s Nuclear Power Plant Siting: Quelling Resistance

By Daniel P. Aldrich

Japan’s government remains firmly committed to a large scale nuclear power program despite sustained resistance from local communities. Recognizing the concerns of many citizens about nuclear power and its health and property risks, the government instituted tactics to smooth the path for its nation-wide energy agenda undertaken in cooperation with private utilities. The responsible government office, the Agency for Natural Resources and Energy (ANRE, or Shigen enerugi cho), honed a wide variety of strategies designed to quell resistance to nuclear power plant siting. Despite innovative and expensive programs such as awards ceremonies for cooperative local government officials, pro-nuclear curricula for local schools, and extensive subsidies for host communities, the time necessary for siting new plans continues to increase and some plans have been defeated. Local communities and anti-nuclear activists remain resistant to central government inducements and will no doubt seek to block future siting attempts.

Germany, Italy, England, and other Western nations have backed away from initial enthusiastic support for commercial nuclear power, and pro-nuclear forces within the United States remain unable to overcome regulatory ratcheting, local resistance and economic difficulties which mire attempts at building new reactors. Japan, on the other hand, has developed one of the most advanced civilian nuclear energy programs in the world, with further plans for fast breeder and MOX-utilizing reactors, nuclear fuel recycling, and new plants. As of the summer of 2005, Japan has 53 operational nuclear power plants, with an additional 3 under construction and 8 reactors being prepared for construction. Japan is the world’s third largest producer of electricity via nuclear power, behind the United States and France. Its production capacity from its plants is larger than nations like Russia, Germany, Korea, and Britain. The only nation ever to have experienced first hand the effects of atomic weapons has developed a nation-wide nuclear program which provides close to forty percent of its generated electricity.

To explain this anomaly, some researchers focused upon the difficulties anti-nuclear groups have in overcoming centralized, exclusionary procedures which block attempts at slowing the plans of government and private industry (Tabusa 1992; Cohen, McCubbins, and Rosenbluth 1995). Others reference Japan’s supposedly passive political culture, in which deferential citizens rarely mobilize against state authorities (Nakamura 1975). This article instead illuminates attempts by the central government to overcome anti-nuclear sentiment through a variety of policy tools. I show that the Japanese state not only created new strategies in an attempt to smooth the siting of nuclear power plants, but that it continually upgraded and refined these tools as it learned from its experiences. Here I support previous work which found that bureaucracies and political leaders are rarely swayed by public opinion; instead, they attempt to sway it. Despite attempts at winning “hearts and minds” and a variety of innovative techniques designed to alter local preferences, the Japanese state has been fighting a losing battle.

Like other democracies which have promoted energy plans involving nuclear power, Japan faced increasing resistance to atomic reactors over time (Rosa and Dunlap 1994). Although private utility companies in Japan carry out the siting of nuclear power plants much like private firms in North America, the Japanese government plays a fundamental role in the process. ANRE identified the possible obstacles to its energy plans, primarily fishing cooperatives, local government leaders, youth, and women, and targeted them with programs designed to make them more receptive to nuclear power and hence more likely to host a nuclear reactor in their community or refrain from opposing one elsewhere.

Specific State Strategies

The Japanese central government, like all other nations, has the power to forcibly extract land from local citizens for projects deemed in the public good. The desire to use expropriation was especially strong during the Maki-machi wrangle, when, many years after the siting process of a nuclear power plant had begun, local citizens successfully brought about a referendum (jumin tohyo) which prevented the sale of land to the utility. Internal memos from ANRE officials to their colleagues indicate that all agreed that the plant would fit under the definition of “public enterprise” but that the possible negative reaction combined with the difficulties in convincing the legal authorities that the plant could not have been located in another spot prevented them from using the powers available to them. In interviews ANRE officials stated that they felt that if they had used land expropriation in the Maki case, future mayors who might incline to be pro-facility would respond negatively (Interviews, Fall 2002).

Rather than using force and land expropriation, government officials have sought to smooth the siting process through policy instruments which persuade and entice local citizens. In 1964 the Japanese government decided to promote its plans for nuclear power development by establishing a Nuclear Power Day to be celebrated yearly on 26 October. Since those early days of pro-nuclear public relations campaigns, central government ministires have developed more sophisticated tools in handling potential host communities. For example, in the case of Kaminoseki, as negotiations between land owners, fishermen, and the utility dragged on in the 1980s, ANRE officials visited local citizens and gave pep talks about the need for the plants in the scheme of the overall energy plan (Interviews, November 2002). Bureaucrats began establishing branch offices and “atomic energy centers” in 1972 in possible host localities to show the seriousness of government intent and provide officials more direct access to their “constituents.” These centers allowed citizens the rare opportunity to speak directly with local government representatives.

Mayors and other local elected officials feared that anti-nuclear sentiment could cost them future elections if they openly supported plans for nuclear siting. In response, the ANRE and the Prime Minister’s office began a program in the early 1980s that celebrated and rewarded local government officials who had contributed to the success of nuclear power plant and other energy facility siting. The Citation Ceremony for Electric Power Sources Siting Promoters (Dengen ricchi sokushin korosha hyosho) occurs yearly in July and provides these officials with the opportunity to appear in national media and gain acclaim for their actions.

Government officials early on recognized the power held by local fishermen’s’ cooperatives, gyogyo rodo kumiai. Because Japanese utility companies decided to utilize water drawn in from the ocean for cooling down their nuclear reactors, the cooperation of fishing cooperatives became vital to the success of Japan’s nuclear power industry. Japanese law requires companies which impinge upon the fishing areas of cooperatives to purchase the rights to those areas, with the fishing cooperative needing a two-thirds majority to approve compensation plans for selling those fishing rights. Without the approval of the local cooperatives, siting cannot continue. Cooperatives have a number of reasons to resist siting, primary among them being the permanent loss of fishing rights to the utility. Beyond that, however, cooperatives have feared the higher temperatures of water discharged by the plants will negatively affect aquatic life and its habitats. Further, utilities were notorious for having discharged polluted and radioactive liquids along with the water back into the ocean, resulting in Minamata disease and other disasters.

Reluctant fishing cooperatives that have refused to strike deals with authorities have forced cancellation or lengthy delays on a number of projects. In Kaminoseki, the fishing cooperative at Iwaishima continues to negotiate with government and business representatives, resulting in the ever lengthening “lead time” necessary for the plant’s construction (Interview with local activist, 4 November 2002). To diminish opposition among fishing cooperatives, the government has sponsored job creation through fish farms, published reassuring studies of the effects of nuclear power discharge in fishing magazines, and worked to ensure that fish and other local crops will find markets despite possible concerns over “contamination.”

The largest tools in the government’s arsenal are the Three Power Source Development Laws, known as the Dengen Sanpo, which provide enormous subsidies for communities hosting nuclear power plants. By 2002, a community accepting a 1.35 million kW reactor could receive as much as 450 billion yen from the government — an enormous sum for rural local governments which regularly struggle with deficits. Nevertheless, resistance continues to stall new siting plans. The government has been unable to spend the total amount of money collected for the Three Power Source Laws through an “invisible” tax levied on all power consumption.

Conclusions: A Contentious Road Ahead

Hayden Lesbirel’s work on nuclear power plant siting in Japan, focusing primarily on private sector bargaining (Lesbirel 1998), looked only indirectly at the role of the state while Samuels’ book on Japanese energy markets focused on the reciprocal relations between private utility companies and the central government (Samuels 1987). As a result, many analysts have categorized Japan’s nuclear power plant siting environment as a purely “voluntary market”, making only occasional reference to the role of the central government. Focusing directly on the activities of the state, this article revealed the wide ranging efforts of the central government to alter the preferences of citizens and smooth the siting of controversial facilities.

Political theorists often utilize normative models of democratic governance in which the goals and values of citizens drive politicians and hence bureaucrats to create new programs and advance the society toward a shared future. In Japan’s facility siting environment, this is reversed: non-elected officials, working in conjunction with electric power companies, seek to alter citizen preferences in order to achieve the state’s goals of energy independence. The state designed flexible and institutions to overcome resistance rooted in concerns about risk and inequity through the use of payments, public relations, and reassurance. While Japanese political culture and in-place procedures may have reduced resistance among some citizens, ANRE’s creation and then improvement of educational, compensatory, and persuasive policy tools have increased barriers to collective action against the state.

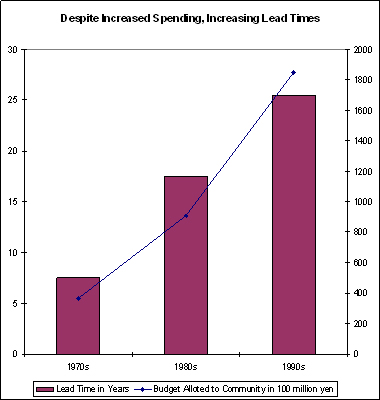

Nevertheless, despite years of such programs and hundreds of millions of dollars of expenditure on incentive, capacity, and symbolic policy instruments, citizens have become increasingly immune to such techniques. Progressively more active and organized movements have utilized citizen referenda, mayoral and town council recalls, and information dissemination to combat central government and utility efforts at resistance-free siting. Many citizens no longer accept explanations from central government bureaucrats at face value, and have pushed the state to enact more open and citizen-centered siting procedures. These actions from citizens, combined with fatal management errors and recent cover ups of poor reactor maintenance by private utilities have created a situation in which green-fields siting of new reactors now seems all but impossible and lead times continue to grow. The time necessary for negotiation and construction for nuclear power plants has tripled over the past three decades.

ANRE and other government ministries worked to improve their strategies, increasing the amounts of compensation, broadening their targets, and extending the time period of availability for payments along with providing more accurate mechanisms for citizen feedback and demands. Nonetheless, recent siting rates reveal that these measures have largely failed. Perhaps the most important lesson from this study has been that despite the use of flexible and adaptive institutions in siting processes, even the best designed and improved techniques cannot assure siting success in an era of increasingly active and concerned citizenry.

Sources:

Cohen, Linda, McCubbins, Mathew, and Rosenbluth, Frances. (1995). “The Politics of Nuclear Power in Japan and the United States,” in Peter Cowhey and Mathew McCubbins, eds, Structure and Policy in Japan and the United States. Cambridge University Press, pp. 177 -202.

Lesbirel, S. Hayden. (1998). NIMBY Politics in Japan: Energy Siting and the Management of Environmental Conflict. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Nakamura, Kikuo, ed. (1975). Gendai Nihon no Seiji Bunka [Contemporary Japanese Political Culture] Kyoto: Mineruba.

Rosa, Eugene and Dunlap, Riley. (1994). “Poll Trends: Nuclear power: Three decades of opinions,” Public Opinion Quarterly Vol. 58 Issue 2 pp 295 –324.

Samuels, Richard. (1987). The Business of the Japanese State. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Tabusa, Keiko. (1992). Nuclear Politics: Exploring the Nexus between Citizens’ Movements and Public Policy in Japan. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Columbia University.

Daniel P. Aldrich, Assistant Professor of Political Science at Tulane University, has published articles in Comparative Politics, Political Psychology, Asian Journal of Political Science, and Social Science Japan. This article, prepared for Japan Focus, draws on and extends a chapter published in an edited volume entitled Managing Conflict in Facility Siting: an international comparison (Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar 2005). Posted at Japan Focus June 13, 2005.