Jack London: The Adventurer-Writer who Chronicled Asian Wars, Confronted Racism—and Saw the Future (Revised)

Daniel A. Métraux

He stood among the Japanese soldiers wearing a weather-beaten visored cap over his short, dark hair and a rough hewn jacket covering his broad soldiers, a cigarette angling away from his square jaw and a camera dangling from his gloved hand. As they studied documents, the Japanese troops contrasted with Jack London in their box hats and high collared uniforms. A photographer present immortalized London looking like the adventurer and writer that he was, one drawn to the battle like a missionary to his calling, who skillfully recorded the machinations of great powers while sympathizing with the underdogs who struggled to survive.

|

London negotiates passage with a Japanese officer in Korea during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05 |

Jack London (1876-1916), easily the most popular American writer a century ago, is still praised for his Yukon novels and short stories such as The Call of the Wild, White Fang and To Build a Fire. However, his visits to Japan, Korea and Manchuria; his factual, hard hitting coverage of the Russo-Japanese War (1904-05); his astute short stories about Sino-Japanese competition; his prophetic essays predicting the rise of the Pacific Rim, and his call for respect and constructive interaction between Americans and Asians over “yellow peril” hysteria are undeservedly forgotten. These salient aspects of London’s life deserve to be remembered and respected. They evidence his keen intelligence, painfully accurate vision of the future and the progressive and humane values that are still needed to bridge the East and West.

The Yellow Peril Threatens the West?

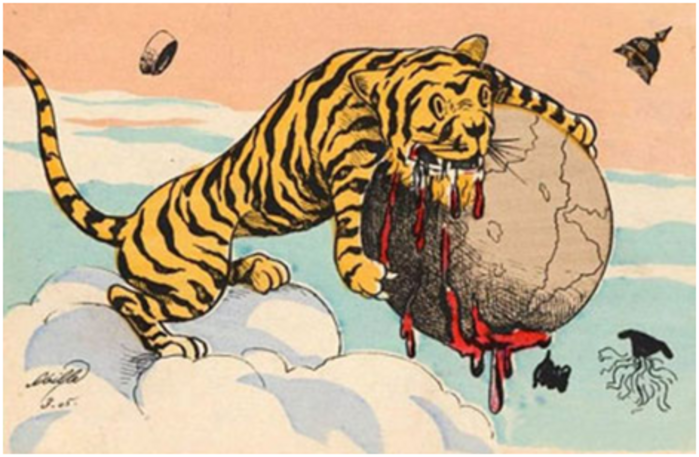

Today the term “The Yellow Peril” — but not necessarily the fears and fantasies that it engenders — has gone out of fashion. But in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Westerners’ dreams about the “superiority” of their civilization competed with their nightmares of Oriental hordes swarming from the East to engulf the advanced West. This was a popular theme in the day’s literature and journalism, which London knew well. The term “Yellow Peril” supposedly derives from German Kaiser Wilhelm II’s warning following Japan’s defeat of China in 1895 in the first Sino-Japanese War. The expression initially referred to Tokyo’s sudden rise as a military and industrial power in the late nineteenth century. Soon, however, its more sinister meaning was broadly applied to all of Asia. “The Yellow Peril” highlighted diverse Western fears including the supposed threat of a military invasion from Asia, competition to the white labor force from Asian workers, the alleged moral degeneracy of Asian people and the spectre of the genetic mixing of Anglo-Saxons with Asians.1

|

The Russo-Japanese War saw Japan alter the world balance of power that the West once dominated, triggering viceral fears of a yellow peril |

Many writers and journalists in the early 1900s wielded an unflattering pen when writing about Asians, boasting of Anglo-Saxon superiority over the “yellow and brown” Asians. The Hearst newspapers stridently warned of the “yellow peril”. So did noted British novelist M. P. Shiel in his short story serial, The Yellow Danger. One finds similar views in Kipling’s poem “The White Man’s Burden” and in some of his stories and novels.

London in the Dock: His Defense is on the Page

John R. Eperjesi, a London scholar, writes that “More than any other writer, London fixed the idea of a yellow peril in the minds of the turn-of-the-century Americans…”2 Many biographers quote London, just after his return from covering the first months of the Russo-Japanese War for the Hearst newspapers in 1904, as telling a coterie of fellow socialists of his profound dislike for the “yellow man.” Biographer Richard O’Connor quotes Robert Dunn, a fellow journalist with London during the Russo-Japanese war, as saying that Jack’s dislike of the Japanese “outdid mine. Though a professed socialist, he really believed in the Kaiser’s ‘yellow peril.’”3

Are these charges correct? If so, they would cast London as a bigot and alarmist.

In fact, a close examination of London’s writing shows the opposite: he was ahead of his time intellectually and morally. His Russo-Japanese war dispatches from Korea and Manchuria around 1904-5 are balanced and objective reporting, evincing concern for the welfare of both the average Japanese soldier and Russian soldier and the Korean peasant, and respect for the ordinary Chinese whom he met. As perhaps the most widely read of the journalists covering that war, London emerges as one of the era’s writers who sensed that the tide of white “superiority” and Western expansionism and imperialism was receding.

His positive views of Asians can be traced back a decade earlier to his first published stories and later writing such as his essays “The Yellow Peril” and “If Japan Awakens China” and his short story, “The Unparalleled Invasion” — see below. Even as many Americans held racist beliefs about Asians, London expressed more liberal views.

Japanese Aggression, Chinese Pride

In addition, as an analyst, London’s deep understanding of how the industrial, politico-strategic and social worlds were profoundly changing surpassed that of his peers. His fiction and essays explored the appearance of new industrial powers in the East, as well as Western counter moves and inter-Asian tensions, too. London shrewdly predicted elements of the coming age of revolution, total war, genocide and even terrorism. This renders his writing painfully relevant. As Jonah Raskin observed, “In a short, volatile life of four decades, Jack London (1876-1916) explored and mapped the territory of war and revolution in fiction and non-fiction alike. More accurately than any other writer of his day, he also predicted the shape of political power – from dictatorship to terrorism – that would emerge in the twentieth century, and his work is as timely today as when it was first written.”4

For instance, during and after his time in Korea and Manchuria, London developed a complicated thesis in his 1904 essay, “The Yellow Peril,” envisaging the rise first of Japan and then China in opposition as major twentieth century economic and industrial powers.

London’s starting point was his suspicion that Japan’s imperial appetite exceeded its swallowing of Korea in the Russo-Japanese War. He anticipated that Tokyo would eventually take over Manchuria and then attempt to seize control of China in the attempt to use China’s vast land, resources and labor for its own benefit.

London knew that Japan’s strength at the turn of the twentieth century lay in its ability to use Western technology and its national unity. London and some other contemporary writers, as well as many politically attuned Asians recognized that Japan’s defeat of Russia was a turning point in a history of Asian subjugation to white imperial powers. Japan’s victory called into question as no previous event the innate superiority of the white race.5

However, London believed that there were severe limits on Japan’s ability to become a leading world power. However impressive its initial gains, Tokyo would falter from lack of “staying power.” One reason was that it was too small. Although it had humbled Russian forces, London believed that it was not sufficiently powerful to create a massive Asian empire, still less to militarily or economically threaten the West. Seizing “poor, empty Korea for a breeding colony and Manchuria for a granary” would greatly enhance Japan’s population and strength — but that was not enough to challenge the great powers.

Simultaneously, London saw that Asians themselves would be antagonists. He clearly distinguished between the Chinese and Japanese, at times — ironically — referring to the Chinese as the “Yellow Peril” and the Japanese as the “Brown Peril.” Japan would launch its crusade promising “Asia for the Asiatics” as its clarion call, but its aggression would catalyze Chinese resistance.6

China’s Rise Provokes the White Peril’s Germs

In “The Yellow Peril,” London’s conclusion left the reader hanging. Although aroused, China’s vast potential is hindered. Its leaders hew tenaciously to the past. Clinging to power and tradition, they refuse to modernize and so China’s fate is uncertain. London does not tell the reader who will prevail. However, in his 1906 short story, “The Unparalleled Invasion,” London develops the theme of China’s rise. The Japanese are expelled from China and are crushed when they try to reassert themselves there. China then becomes a major power.

Writing a century ago, London warned that the imperial West, blissfully ignorant of what awaited it, was living in a bubble. The shift of power to Asia was the prick that would burst it. The transition would be peaceful because Asia’s rise was primarily economic, but eventually war between East and West was inevitable because China challenged the economic might of the West. Although critics have read different messages into the story, the clear irony is that the West is the paranoid aggressor. It is a White Peril and China is the innocent victim.

But “contrary to expectation, China did not prove warlike [so] after a time of disquietude, the idea was accepted that China was not to be feared in war, but in commerce.” The West would come to understand that the “real danger” from China “lay in the fecundity of her loins.” As the 20th century advances, the story depicts Chinese immigrants swarming into French Indochina and later into Southwest Asia and Russia, seizing territory. Western attempts to slow or stem the Chinese tide all fail. By 1975 it appears that this onslaught will overwhelm the world.

With despair mounting, an American scientist, Jacobus Laningdale, visits the White House to propose eradicating the entire Chinese population. He aims to drop deadly plagues from Allied airships over China. In May, 1976, the bombers appear over China and release a torrent of glass tubes.7 At first nothing happens, then an inferno of plagues gradually wipes out the entire population. Allied armies surround China and all Chinese die. Even the seas are closed because 75,000 Allied naval vessels blockade China’s coast. “Modern war machinery held back the disorganized mass of China, while the plagues did the work.”8

Here, let’s praise London’s piece as a stern warning about bio-warfare. He wrote when strategists were investigating the new concept of germ weapons. London sounds an alarm over such hazards that world powers ignored as they rushed into the gas clouds and carnage of World War I. Decades later, Japan would unleash bio-warfare against China’s cities in the China-Japan War of 1937-45, and China and North Korea would charge the US with waging germ warfare during the Korean War.

More broadly it is worth reflecting on London’s vision in light of the changes of the last few decades in East Asia. Above all, this has been a story of the rise of East Asia. First Japan’s, and later Taiwan’s South Korea’s and China’s, wealth and power have grown spectacularly. East Asia’s resurgence has challenged the status quo of American and European dominance. Now the exponents of the “China Threat” school insist that this could auger a military challenge that transforms the balance of power in Asia and the Pacific.

In short, long before Samuel Huntington, London anticipated a clash of civilizations. His readers see how the vast cultural differences that divide the West from China spark hatred and malice in the former. The focus here is not the Chinese danger to the West, but its reverse. As Jean Campbell Reesman points out, “London’s story is a strident warning against race hatred and its paranoia, and an alarm sounded against an international policy that would permit and encourage germ warfare. It is also an indictment of imperialist governments per se.”9

He anticipates that the wars of the twentieth century will exact an unprecedented death toll among armies and civilians. Indeed, the world can regret London’s prescience. To avoid this fate, London urges the West to understand the new Asia and to live with non-white peoples in a spirit of brotherhood.

Conclusion: London the Internationalist Still Speaks to Us

London’s views of Asians and the Pacific’s other non-white people became more refined in the last seven years of his life during and after his 1907-1909 trip to the South Pacific aboard his decrepit schooner, the Snark. London’s increasingly pan-national world view led to his 1915 recommendation of a “Pan-Pacific Club” where Easterners and Westerners could meet congenially in a “forum” to exchange views and share ideas as equals. Far from being the thoughts of a racist, they are the vision of an internationalist. In particular, London wanted Americans and Japanese to associate to promote mutual respect and understanding.

Jack London traveled extensively during his short but active life. He encountered diverse cultures that he tried to understand. He empathized with the downtrodden in the United States, Europe, East Asia and the South Pacific. His “Pan-Pacific Club” essay is his final appeal for the West to overcome stereotypical view of Asians as inferior peoples who needed Western domination for their betterment. Although London died in 1916, the words of this realistic and humane writer still speak to us.

Jack London Reporting From Manchuria

[Editor’s Note: The Hearst newspaper empire hired Jack London to be its chief correspondent covering the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905). When London arrived in Tokyo in late January 1904, he found that the Japanese government would not allow foreign correspondents near its army as it marched north through Korea to meet Russian forces in Manchuria. Refusing to spend the war attending banquets, London raced across Japan searching for a vessel to take him to Korea.

|

London astride Belle in Japan |

After considerable difficulty, he caught up with the Japanese army in late winter 1904 in Korea and accompanied the troops as they marched north through Korea and into Manchuria to confront the Russians. London continued his coverage of the war through June of 1904. The following dispatch followed Japan’s victory over Russian forces in a tense battle for control of the Yalu River between Korea and Manchuria.

“Beware the Monkey Cage”

ANTUNG, Manchuria. May 10th, 1904. The Japanese, following the German model, make every possible preparation, take every possible precaution, and then proceed to act, confident in the belief that nothing short of a miracle can prevent success. Opposed to their three divisions on the Yalu was a greatly inferior Russian force, but the Japanese had to cross the river under fire and attack an enemy lying in wait for them.

By the manipulation of their three divisions, and what of their ruses, they must have sadly befuddled the Russians. At the mouth of the Yalu the Japanese had two small gunboats, two torpedo boats and four small steamers armed with Hotchkiss-guns. Also they had fifty sampans loaded with bridge materials. These were intended for a permanent bridge at Wiju; but they served another purpose—first, farther down the stream. The presence of the small navy and the loaded sampans led the Russians to believe that right there was where the bridge was to be built. So right there they stationed some three thousand men to prevent the building of the bridge. Thus a handful of Japanese sailors kept 3,000 Russian soldiers occupied in doing nothing and reduced the effectiveness of the Russian strength that much.

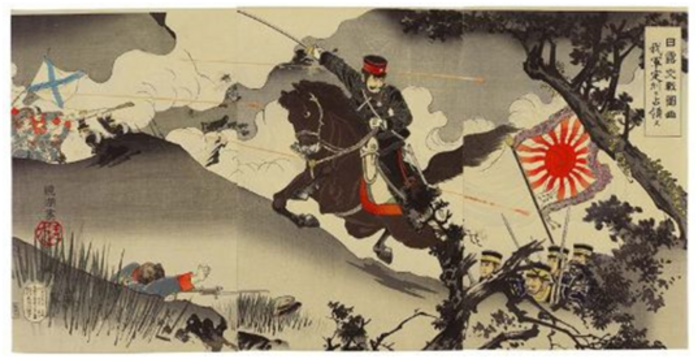

|

Woodblock print depicting Japanese victory over the Russians at Chongju. Kyōko Hasegawa Sonokichi Umezawa horu Illustration of the Russo-Japanese War: Our Armed Forces Occupy Chongju (Nichiro kōsen zuga, wagagun Teishū o senryō su) Ukiyo-e print; Russo-Japanese War 1904 (Meiji 37), March. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Visualizing Cultures. |

Another ruse was the building of a bridge in front of Wiju. This was in plain view of the Russians on the conical hill opposite just east of Kieu-Liang-Cheng, and they consumed much time and powder in shelling it. This was precisely what the Japanese intended for the bridge. While it held the Russian attention, a little farther down the stream the Japanese were at work on another bridge screened by small willow trees on the intervening island, and which, when completed, had never had a shot fired at it.

Have you ever stood in front of a cage wherein there was a monkey gazing innocently and peaceably into your eyes—so innocent and peaceable the hands grasping the bars and wholly unbelligerent, the eyes that bent with friendly interest on yours, and all the while and unbeknown a foot sliding out to surprise your fancied security and set you shrieking with sudden fright? Beware the monkey cage! You have need of more than your eyes; and beware the Japanese. When he sits down stupidly to build a bridge with his two hands before your eyes, have a thought to the quiet place behind the willow-screen where another bridge is builded by his two feet. He works with his hands and his feet, he works night and day, and he never does one thing expected of him, and that is the unexpected thing.

The night of April 29th and the day of the 30th was an anxious time for the Japanese. Their army was cut in half, and it was no less than the Yalu that divided it. One-third of its force, the Z division, had crossed the river to the right and was in Manchuria. They had no very accurate knowledge of the Russian strength, and it was not beyond liability that the Russians might make a counter attack on the Z division and destroy it. So the X and Y divisions on the south bank were in momentary readiness to prevent this by delivering an attack upon the Russians straight across the river. But there was no need for this. The Russians were not in sufficient force to attack a single division, advancing as it was across mountainous country. This, in turn, the Japanese did not know, but they prepared for the possibility as they prepare for everything.

The Ai-ho river flows out of Manchuria and enters the Yalu valley a mile or more above Kieu-Liang-Chen. It also flows past that village, close to the Manchurian shore, thus interposing an obstacle to the advance of the whole Japanese army (even the Z division), after it had crossed the Yalu proper. The crossing of the Ai-ho was seriously menaced by the sixteen guns of the Russian right on the conical hill. The day’s work for April 30th was to put these sixteen guns out of business. The Japanese bent themselves to the task. It was an exposed position and a concentration of fire lasting twenty-five minutes and in which time sixty common shells were thrown, did the work. The Russian fire was silenced and the guns were withdrawn that night! Incidentally the Japanese bombed the Russian camp, carelessly situated where it was exposed from the Korean hills, and wrought great havoc.

On the night of April 30th the X and Y divisions crossed the main Yalu and rested on the sands, with the Ai-ho between them and the Russians. The X division forming the Japanese left, faced the Russian right on the conical hill, and the Y division was extended near the mouth of the Ai-ho; and up the Ai-ho, extended for several miles, lay the Z division. Opposing these three divisions was a Russian actual fighting force of about 4,000 men. The Russian line, extending some six or seven miles, was not intact. In fact, because of the lay of the land, the Russians really occupied two positions—one on and about the conical hill at Kieu-Leng-Cheng, the other at the Ai-ho, from its mouth several miles up.

Against these two positions, occupied by about 2,000 men, was hurled an army of three divisions (probably 25,000 men actually on the spot), backed by a powerful artillery of field guns and howitzers. Prevented by shell fire and shrapnel from doing their best to repel the general attack, and being flanked by an immensely superior force, the Russian left on the Ai-ho broke first and fled in the direction of the Hamatan. The Russian right on the conical hill, fought more, tenaciously, the survivors in turn fleeing toward Hamatan.

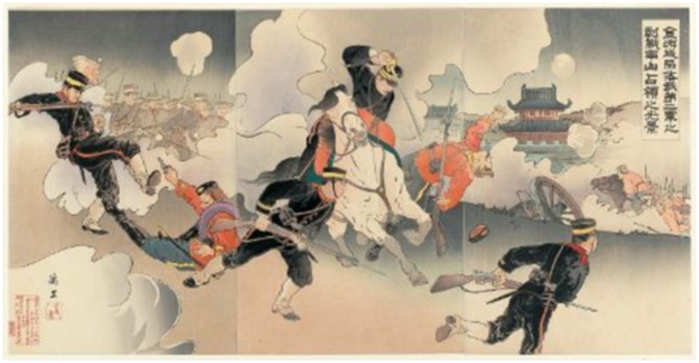

|

Banri Narazawa Kenjirō Umezawa horu Scene of Our Second Army Occupying Nanshan in a Fierce Battle at the Fall of Jinzhoucheng (Kinshūjō kanraku waga dainigun no gekisen Nanzan senryō no kōkei) Ukiyo-e print; Russo-Japanese War 1904 (Meiji 37), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Visualizing Cultures |

The Japanese understand the utility of things. Reserves they consider should be used, not only to strengthen the line or protect the repulsed line, but in the moment of victory to clinch victory hard and fast. The reserves, fresh and chafing from inaction wild to take part in a glorious day, received the order for general pursuit. Right, left and center, they took after the Russians. The field guns, delayed by the Ai-ho followed at a gallop.

The retreat became a rout. The Russian reserves, two regiments, had fled without firing a shot—at least the Japanese have no record of these two regiments. Hamatan is at the conjunction of three roads, six miles to the rear of the conical hill. Down these three roads the Russians ran, coming together and passing on to the main road—the Pekin or Mandarin road. And down these three roads, from left, right, and center, came the fresh reserves, and after them the artillery.

In the meantime, however, far from the Japanese right and outstripping the rest of the pursuit, arrived one company of men in time to cut off fifteen Russian guns and eight maxims. The remnants of the three battalions rallied around the guns. A hasty position was taken. The rest of the pursuing Japanese did not arrive. But one company of men stood between the Russians and the Pekin Road. And it stood. Its captain and three lieutenants were killed. One officer only remained alive. The last cartridge was fired. Those that survived fixed their bayonets ready to receive a charge. And in the moment, left, right, and center, their pursuing comrades arrived.

The Russians were assailed from three sides. The tables were turned but they fought with equal courage. The day was lost; they knew it; yet they fought on doggedly. Night was falling. As the Japanese grew closer the Russians turned loose their horses, destroyed or threw away the breechblocks of their guns, smashed the breeches of the maxims and then, as bayonet countered bayonet, drew white handkerchiefs from their pockets in token of surrender.

One other noteworthy thing occurred in the Japanese pursuit. Midway to Hamatan, flying on the heels of a rout, in the very heat and sweep of triumph, they dropped a line of reserves to receive and protect them should they be hurled back broken and crushed by Russian re-enforcements. Hand in hand with terrifying bravery goes this cold-blooded precaution. Verily, nothing short of the miracle can wreck a plan they have once started to put into execution. The men furnish the unfaltering bravery, confident in their knowledge that their officers have furnished the precaution.

Of course, the officers are as brave as the men. On the night of the 30th, when the army took up its position on the Ai-ho, it was not known whether that stream was fordable. Officers from each of the three divisions stripped and swam or waded the river at many different points, practically under the rifles of the Russians.

“Men determined to die” is the way one Japanese officer characterized the volunteers who answer in large number to every call for dangerous work. Not knowing whether the Ai-ho was fordable, three plans were seriously considered. First, each soldier was to go into action May 1st dressed in cartilage belt and equipped with a rifle and a board, the latter to be used as a means for paddling across the Ai-ho. Second, same garb and equipment with a tub substituted for the board, and third, the strongest swimmers to cross over with ropes, along which, when once fast on the other side bank, the weaker swimmers and non-swimmers could make their way. In any case, had the river not proved fordable, Kipling’s “Taking the Long-Tong-Pen” would have been repeated on a most formidable scale. Surely the Russians would have broken and fled perceptibly before so terrible a charge.

Every division, every battery was connected with headquarters by field telephone. When the divisions moved forward they dragged their wires after them like spiders drag the silk of their webs. Even the tiny navy at the mouth of the Yalu was in constant communication with headquarters. Thus, on a wide-stretching and largely invisible field, the commander-in-chief was in immediate control of everything. Inventions, weapons, systems (the navy modeled after the English, the army after the German) everything utilized by the Japanese has been supplied by the Western world; but the Japanese have shown themselves the only Eastern people capable of utilizing them.

If Japan Awakens China

[London wrote this piece in 1909, five years after his return from Manchuria. He predicts the rise of Japan and its endeavor to transform itself into a major world power by harnessing the labor of four hundred million Chinese. The Chinese, he suggested, would in turn eventually overthrow their conservative leaders, drive out the Japanese and develop a prosperous modern economy. Excerpts.]

The point that I have striven to make is that much of the reasoning of the white race about the Japanese is erroneous, because is it based on fancied knowledge of the stuff and fiber of the Japanese mind. An American lady of my acquaintance, after residing for months in Japan, in response to a query as to how she liked the Japanese, said: “They have no souls.”

In this she was wrong. The Japanese are just as much possessed of a soul as she and the rest of her race. And far be it from me to infer that the Japanese soul is in the smallest way inferior to the Western soul. It may even be superior. You see, we do not know the Japanese soul, and what its value may be in the scheme of things. And yet that American lady’s remark but emphasizes the point. So different was the Japanese soul from hers, so unutterably alien, so absolutely without any kinship or means of communication, that to her there was no slightest sign of its existence.

Japan, in her remarkable evolution, has repeatedly surprised the world. Now the element of surprise can be present only when one is unfamiliar with the data that go to constitute the surprise. Had we really known the Japanese, we should not have been surprised. And as she has surprised us in the past, and only the other day, may she not surprise us in the days that are yet to be? And since she may surprise us in the future, and since ignorance is the meat and wine of surprise, who are we, and with what second sight are we invested, that we may calmly say: “Surprise is all very well, but there is not going to be any Yellow peril or Japanese peril?”

There are forty-five million Japanese in the world. There are over four hundred million Chinese. That is to say, that if we add together the various branches of the white race, the English, the French, and the German, the Austrian, the Scandinavian, and the white Russian, the Latins as well, the Americans, the Canadians, Australians and New Zealanders, the South Africans, the Anglo Indians, and all the scattered remnants of us, we shall find that we are still outnumbered by the combined Japanese and Chinese.

We understand the Chinese mind no more than we do the Japanese. What if these two races, as homogenous as we, should embark on some vast race-adventure? There have been no race adventures in the past. We English-speaking peoples are just now in the midst of our own great adventure. We are dreaming as all race-adventurers have dreamed. And who will dare to say that in the Japanese mind is not burning some colossal Napoleonic dream? And what if the dreams clash?

Japan is the one unique Asiatic race, in that alone among the races of Asia, she has been able to borrow from us and equip herself with all our material achievement. Our machinery of warfare, of commerce, and of industry she has made hers. And so well has she done it that we have been surprised. We did not think she had it in her. Next consider China. We of the West have tried, and tried vainly, to awaken her. We have failed to express our material achievements in terms comprehensible to the Chinese mind. We do not know the Chinese mind. But Japan does. She and China spring from the same primitive stock—their languages are rooted in the same primitive tongue; and their mental processes are the same. The Chinese mind may baffle us, but it cannot baffle the Japanese. And what if Japan wakens China—not to our dream, if you please, but to her dream, to Japan’s dream? Japan, having taken from us all our material achievement, is alone able to transmute that material achievement in terms intelligible to the Chinese mind.

The Chinese and Japanese are thrifty and industrious. China possesses great natural resources of coal and iron—and coal and iron constitute the backbone of machine civilization. When four hundred and fifty million of the best workers in the world go into manufacturing, a new competitor, and a most ominous and formidable one, will enter the arena where the races struggle for the world-market. Here is the race-adventure—the first clashing of the Asiatic dream with ours. It is true, it is only an economic clash, but economic clashes always precede clashes at arms. And what then? Oh, only that will-o’-wisp, the Yellow peril. But to the Russian, Japan was only a will-o’-wisp until one day, with fire and steel, she smashed the great adventure of the Russian and punctured the bubble-dream he was dreaming. Of this be sure: if ever the day comes that our dreams clash with that of the Yellow and the Brown, and our particular bubble-dream is punctured, there will be one country at least unsurprised, and that country will be Russia. She was awakened from her dream. We are still dreaming.

Daniel A. Métraux is Professor of Asian Studies at Mary Baldwin College in Staunton, Virginia. He recently served as president of the Southeast Chapter of the Association for Asian Studies and as editor of the Southeast Review of Asian Studies. His books on Japanese and Asian affairs include The Soka Gakkai Revolution (1994) and Burma’s Modern Tragedy (2004). His most recent book, The Asian Writings of Jack London: Essays, Letters, Newspaper Dispatches, and Short Fiction by Jack London was published by Edwin Mellen Press in 2009. An earlier article on London, “Jack London Reporting from Tokyo and Manchuria: The Forgotten Role of an Influential Observer of Early Modern Asia,” appeared in Asia Pacific Perspectives in June 2008. He wrote this article for The Asia-Pacific Journal. The author thanks Victor Fic for editing this text.

Recommended citation: Daniel A. Métraux, “Jack London: The Adventurer-Writer who Chronicled Asian Wars, Confronted Racism—and Saw the Future,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, 4-3-10, January 25, 2010. ジャック・ロンドン、アジア戦争、「黄禍

Notes

1 See William F. Wu, The Yellow Peril: Chinese-Americans in American Fiction, 1850-1940 (Hamden CT: Archon Books, 1982).

2 John R. Eperjesi, The Imperialist Imaginary: Visions of Asia and the Pacific in American Culture (Hanover: Dartmouth University Press, 2005, 108)

3 Richard O’Connor, Jack London: A Biography (Boston: Little, Brown and Co., 1964), 214.

4 Jonah Raskin, The Radical Jack London: Writing on War and Revolution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 1.

5 John R. Eperjesi, The Imperialist Imaginary, 109.

6 “The menace to the Western world lies not in the little brown man, but in the four hundred millions of yellow men should the little brown man undertake their management.” Jack London Reports, 346

7 See Tsuneishi Keiichi, “Unit 731 and the Japanese Imperial Army’s Biological Warfare Program. See also Stephen Endicott, The United States and Biological Warfare: Secrets from the Early Cold War and Korea. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1998. Critics have strongly challenged Endicott’s key points concerning the alleged use of germ warfare in the Korean War.

8 Jack London, “The Unparalleled Invasion“ in Dale L Walker, Ed., Curious Fragments (Port Jefferson NY: Kenkat Press, 1976), 119.

9 Jeanne Campbell Reesman, Jack London: A Study of the Short Fiction (New York: Twayne Publishers, 1999), 91.