Chris Giles and R. Taggart Murphy

Wrong Lessons Drawn From Asia’s 1997 Financial Crisis: The IMF Revisited

Chris Giles

It is January 15 1998. Standing grim-faced and with arms folded, Michel Camdessus, the International Monetary Fund managing director, peers down as President Suharto of Indonesia signs his acceptance of the latest list of 50 IMF demands. Mr Suharto has no choice, even though many of the intended reforms are politically unpalatable. Such has been the outflow of money from Indonesia over the past six months that the economy would implode if a second international bail-out were refused.

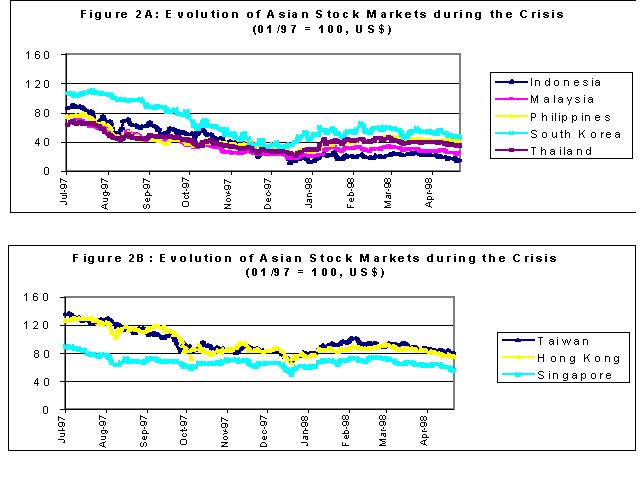

This is the enduring image of the Asian financial crisis, which started 10years ago today with the plunge of the Thai baht after currency speculatorsdestroyed its peg to the dollar. Financial turmoil spread across east Asia,plunging economies into deep recession, bankrupting once-mighty banks and companies, forcing countries into supplication before the IMF and generating much political turmoil.

For Asia, Mr Suharto’s humiliation and subsequent downfall after more than 30 years in power symbolised the domineering attitude of the west and the late-1990s humbling of the Asian tiger economies. “Never again” was the lesson learnt by Asian politicians, whether or not they came from a crisis-hit economy.

With a decade of hindsight, it is clear that the crisis economies of a decade ago Thailand, South Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore and the Philippines suffered only a “temporary setback”, according to David Burton and Alessandro Zanello, who head the IMF’s Asia and Pacific department: “Asia shines in the global economic landscape and its vitality stands out as a remarkable

achievement.”

Economic growth rates are high, if not quite back at pre-crisis levels; the same sort of financial upheaval seems inconceivable today as Asian central banks are stuffed full of ready-to-use foreign exchange reserves; and debts to the IMF have been repaid early. But the effects of the crisis linger in the structure of the region’s economies, in the relevance of the IMF to emerging economies and even in the global balance of economic activity.

The concern now is that the economies of emerging and industrial Asia, along with the US, Japan and Europe, might be vulnerable to a new financial calamity: one that stems from the unprecedented trade imbalances that exist between the US and Asia, yet has its roots directly in the Asian financial crisis of a decade ago.

Few in 1997 were surprised that Thailand’s economy was suffering. With extremely large current account deficits of around 8 per cent of gross domestic product, a vulnerability to speculative attack had been noticed by the IMF, which had recommended a more flexible exchange rate.

Thailand refused. Instead, speculators battled with the central bank through the spring of 1997 over the value of the baht. When the authorities ran out of foreign exchange reserves, they admitted defeat and allowed the currency toplunge on July 2, inflicting great pain on banks and finance companies, which had borrowed in dollars in the belief that the currency would remain pegged.

At this point the consensus view was that Thailand was a special case. But sensing blood, speculators pummelled the currencies of Indonesia, the Philippines and Malaysia through the summer of 1997 even though none of these countries had remotely as large a current account deficit or initial financial

vulnerability as Thailand.

By October, Indonesia went to the IMF for assistance. A furious row broke out over who was to blame for the failure of the initial rescue package, which led ultimately to Mr Suharto’s humiliation in January 1998. The country was already on the road to political turmoil, devaluation and hyperinflation.

South Korea had seemed immune but it, too, fell victim to an international rush to the exit. The currency dropped like a stone in November 1997, losing almost half its pre-crisis value by December, threatening the world’s financial system. The capital outflow was stemmed only when the IMF persuaded foreign creditors to roll over loans as the year ended.

In a few short months, a contagious financial crisis had spread through the region. Although not much recognised at the time, the common features were that each crisis economy had enjoyed a period of high foreign capital inflows in short-term assets before the crisis hit, they each had current account deficits, fixed exchange rates to the dollar, poor regulation of their banking and financial sectors and they each had massive borrowing in foreign currency. The first three features ensured vulnerability to a crisis while the final two guaranteed that the crisis would be painful.

As Anne Kruger, IMF deputy managing director in 2001-06, has said: “Devaluation then left financial institutions facing massive losses, or insolvency …The contraction in GDP that most crisis countries experienced made things even worse, of course, because the number, and size, of non-performing loans grew rapidly. The further weakening of the financial sector inevitably had adverse consequences for the economy as a whole. In short, the crisis economies found themselves in a vicious downward spiral.”

For the IMF itself, the upshot was that it lost the confidence of the most rapidly expanding region in the world. Asian academics such as Takatoshi Ito, a professor at Tokyo University, argue that it provided too little money with too many conditions: “The IMF lost credibility as an institution that could give a seal-of-approval effect to financial markets to stop capital outflows.” He contrasts its actions with subsequent crises in Latin America, particularly in Argentina, where it provided too much money with too few conditions.

The fund concedes that some of its fiscal advice was too harsh, that it took time to get the conditions of its loans right and that it is still struggling to regain credibility and legitimacy in Asia.

The consequence for Asian economies was initially bleak. In 1998, Indonesia, Thailand, South Korea, Malaysia and the Philippines each saw economic activity fall by between 8 per cent and 13 per cent, creating deep social problems. But growth returned quickly in what became known as the “V-shaped recovery”.

The lost output of 1998 was never recovered and the Asian Development Bank calculates that the post-crisis average growth rates “have slipped by an average 2.5 [percentage points] in the five countries that were most directly affected”. The main reason for slower growth has been a sharp decline in the rate of investment as a share of GDP in each of the economies, which allowed the

countries to move from having persistent trade deficits to surpluses but also slowed both actual and potential rates of economic expansion.

In a recent study (Ten Years after the Crisis: The Facts about Investment and Growth, Asian Development Bank) the Asian Development Bank says it is difficult to see why investment rates have fallen so far in the crisis countries, except for South Korea where its prosperity would naturally suggest lower investment. It suggests that “firms and investors may now be more circumspect than a decade ago” and recommends more effective regulation, better governance, greater competition and improved financial systems as the route back to the pre-crisis growth rates.

What people in Asia are reluctant to concede, but US academics such as Nouriel Roubini of New York University claim, is that the lesson learnt by Asia was the wrong one.

Asia learnt that it must never again allow itself to be vulnerable to capital outflows. Governments have managed their currencies this decade to ensure they have low exchange rates and trade surpluses. The biggest emerging Asian economy, that of China, studied the lesson particularly closely, even though capital controls had limited hot money flows in the 1990s.

It has since accumulated foreign exchange reserves of more than $1,200bn (GBP600bn, 892bn) at a rate that is now approaching $40bn a month. According to Prof Roubini, Asian countries led by China have in effect returned “to fixed exchange rates in spite of the rhetoric of a move to floating rates”.

Initially, this policy of buying dollars to hold currencies down was benign, because the crisis economies needed to rebuild their foreign exchange war chests to prevent a repeat of the crisis and China was still relatively insignificant in the global economy. But all Asian countries now have vastly more reserves than are needed to cover their public and private sector short-term debts.

The Bank for International Settlements, the central bankers’ bank, concluded in typically understated language last week that “the stock of reserves does appear to be well above standard measures of adequacy based on liquidity considerations alone”. China is now the world’s fourth largest economy, with a rapidly rising share of global exports.

Alone, the post-crisis actions by Asian countries would not have created the vast trade imbalances of this century. To be stable, those also required the US to become the consumer of last resort. The Federal Reserve slashed interest rates in 2001 and the government cut taxes in response to the recession of thebeginning of the decade, encouraging Americans to spend their way back to prosperity.

These actions ensured that US and Asian policies were in alignment, with unconstrained spending and trade deficits in the former balanced by mercantilismand trade surpluses in Asia.

The result has been an unbalanced global economy, with Asian countries arguably too dependent on exports to the US and building up unnecessary foreign currency reserves, while the US economy can be seen as distorted towards non-tradable services such as real estate.

This potentially fragile state of the world’s economy has continued for much longer than many thought possible, even with periodic fretting at the IMF and elsewhere. The unanswerable question is how long such imbalances can continue.

The IMF is concerned that a hard landing in the US could lead to a painful slowdown in Asia, undermine the fragile balance in world currency and financial markets and raise the threat of protectionism. With Asian countries’ financial systems still weak, particularly in China, the wider Asian economy is vulnerable to a sudden change of view about its prospects.

In the current fragile global equilibrium, all countries like to present themselves as the helpless victims of other countries’ economic choices and so not to blame. That makes them reluctant to take the hard medicine needed to move to a more sustainable world economy. Achieving a co-ordinated response greater consumption and investment in Asia alongside greater savings and the production of tradable goods in the US has proved notoriously difficult.

No one knows whether Asian governments would learn to spend heavily if demand from elsewhere diminished. Optimists believe they would; pessimists suggest that it is already in China’s self-interest to allow its citizens to consume more, yet it does not pursue policies that encourage spending. There is also little sign of US consumers rediscovering the habit of saving.

So while the impact of the crisis a decade ago seems long gone, its lasting legacy has a profound effect on the development of the global economy. It is a bequest that, while temporary, looks ever more intractable.

Corporate groups are pressed to reduce their opacity

Before the Asian crisis erupted in July 1997, corporate governance in emerging markets received minimal attention. After the dramatic outflow of funds from Thailand, South Korea, Indonesia and other countries in the region, the subject was transformed into a political hot topic, writes John Plender.

International policymakers concluded that improved corporate governance was part of the key to promoting more stable capital flows to developing countries to lessen their vulnerability to the vagaries of hot money. For the Group of Seven leading industrial nations, along with the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, it became a priority in responding to the crisis.

Whether better corporate governance could have helped prevent a debacle whose origins were primarily financial seems implausible. Efforts to improve governance have also proved irrelevant in terms of reducing financial vulnerability in the region. The commitment of Asian countries to preventing a repetition of this economic catastrophe has led to an accumulation of official reserves on a scale that far exceeds what is needed to prevent speculative runs on their currencies.

That said, the impetus for corporate governance reform in the region has not gone away. Initiatives such as the Asian Roundtable on Corporate Governance, organised by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, foster efforts to address shortcomings, as in a meeting in Singapore last month where delegates pledged themselves to further reforms.

A recognition is growing, too, of the role corporate governance plays in enhancing corporate performance, reducing the cost of capital and promoting capital market efficiency. Above all it has been the spur to reform arising from corporate scandals. Foremost among those have been a fraud at Procomp, the Taiwanese Enron, and criminal mis-statements in relation to derivative losses at China Aviation Oil in Singapore. A host of other cases across the region have involved the exploitation of minority shareholders by controlling families or government shareholders. But after a decade of reforms, Asia’s company law frameworks and corporate governance codes are close to global best practice. The flaws are largely in implementation and enforcement.

The biggest challenge stems from the structure of Asia’s corporate sector. Roughly two-thirds of listed companies and nearly all private companies are family-run. Asian families tend to run large interlocking networks of subsidiaries and sister companies that include partly-owned quoted companies. This gives them a degree of control over operations and cash flow that is disproportionate to their equity stake.

The extent of their ownership is often opaque. Concentrated and convoluted structures lend themselves to related-party transactions whereby family shareholders can exploit outside investors.

In China the controlling shareholder is often the state. Chinese provincial governments have been particularly adept at expropriating minority investors.

There was general agreement at the roundtable that disclosure requirements on related-party transactions should be strengthened and that regulators needed a greater capacity to monitor dealings and impose sanctions. On the wider governance agenda, obvious priorities include clarifying and strengthening directors’ duty to act in the interests of the company and all its shareholders, prohibiting the indemnification of directors for breaches of that fiduciary duty and entitling investors to pursue class actions.

This is easier said than done. The judicial infrastructure in Asia is often underfunded and beholden to powerful interests. The political will to reform is frequently absent: corporate governance is not politically sexy without the spur of corporate scandal. Stock exchange authorities are subject to conflicts of interest since their desire for a high volume of initial public offerings and share dealings can militate against regulation and supervision.

Accountancy and audit quality remains patchy. Accountancy firms have difficulty maintaining uniform audit standards across the region.

A striking governance lacuna concerns the role of institutional investors. Asian institutions have been very passive. Jamie Allen, secretary general of the Asian Corporate Governance Association, points out that a growing number of foreign investors such as Calpers, TIAA-Cref, Hermes, F&C and British Columbia Investment Management, together with advisers such as Governance For Owners are engaging with company managements behind the scenes. But it is, he adds, a relatively small group. The same is true of those engaged in more high-profile activism.

The reality is that the vast majority of institutional investors in Asia do not even vote their shareholdings. Conflicts of interest are largely to blame. Few want to alienate corporate managers from whom they hope to win fund management business. Nor do they want to jeopardise their own access to management.

When economies are buoyant and markets are high, bad governance is too readily overlooked. But in financial markets, history has a nasty way of repeating itself, if never in quite the same way. The current state of most Asian economies’ balance sheets makes a repeat of the 1997-98 outflows inconceivable. But that does not mean stock markets are immune from a dramatic plunge, followed by a renewed cycle of scandal-induced corporate governance reform.

Chris Giles is Economics Editor, The Financial Times.

This article appeared in The Financial Times, July 1, 2007.

Japan, the United States and the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997: reflections a decade On

R. Taggart Murphy

Chris Giles suggests in his piece that Asian countries may have drawn the “wrong” lessons from Asia’s 1997 Financial Crisis. They were determined never again to find themselves vulnerable either to the sudden capital outflows that precipitated the crisis or the dictates of the IMF that arguably exacerbated it. So countries such as Thailand, South Korea, Indonesia and Malaysia – not to mention China — set about accumulating foreign exchange reserves far in excess of their import and debt service needs. Denominated largely in U.S. dollars, these reserves were acquired via trade surpluses and have fostered eye-popping imbalances: huge U.S. trade deficits that are the flip side of Asia’s lopsided surpluses, export-dependent Asian economies, and a U.S. economy “distorted towards non-tradable services such as real estate” that spends like the proverbial drunken sailor.

The sheer, unprecedented size of these imbalances frightens analysts such as Giles. While he concedes that Asia’s response to the earlier crisis “makes a repeat of the 1997-98 outflows inconceivable”, he frets – like many — that something, somewhere is going to give with all kinds of potentially nasty consequences that we can barely foresee. He laments the state of corporate governance in Asia, but admits that bringing about greater transparency and accountability is “easier said than done.”

Back in 1965, the satirist Tom Lehrer mocked the supposed bravery of soldiers in the “folk song army” standing up in crowded campus coffee shops to plea for such controversial goals as peace and brotherhood. Calls for accountable management and transparent corporate governance in the pages of the global financial press have a similar ring. Giles knows this, which is why he acknowledges that the notion that “better corporate governance could have prevented a debacle whose origins were primarily financial seems implausible.”

So we have a conundrum. Asia’s economies may have learned the “wrong lesson” from the crisis, but like immune systems that, once exposed, develop the ability to ward off a particular strain of a given pathogen, they have made themselves largely invulnerable to a repeat of the events of the late nineties. Alas, they may be unable to cope with a new pathogen whenever and wherever such might appear and in the meantime, the antibodies they developed for the 1997 infection have provoked an allergic reaction in the form of runaway imbalances. It would be really, really great if these economies had better corporate governance. But all the transparency and good governance in the world wouldn’t have helped them much back then and would not lessen the imbalances that have developed since. And things being what they are, better corporate governance is probably not going to happen. The snowballing imbalances look terribly frightening, but they have “continued much longer than many thought possible.” Meanwhile, an IMF that was conceived back in 1944 precisely to treat such imbalances is as clueless as everyone else. While “concerned that a hard landing in the US could lead to a painful slowdown in Asia” not to mention “undermine the fragile balance in world currency and financial markets” the IMF has “lost the confidence of the most rapidly expanding region in the world.” Even if the IMF doctors knew what to do about the imbalances, which they don’t, no one will listen to them any more.

This history is important today for two reasons. First, the carry trade is back and at levels that may exceed those of the mid-nineties. The BOJ is continuing to pump money into the Japanese banking system via its low interest rate policies. While the banks are in better shape now than they were a decade ago, domestic lending is still anemic and large amounts of money continue to leak overseas via the carry trade, fueling asset price surges around the world. No one now can predict with certainty which of these surges bears the seeds of a systemic crisis, although given market tremors last week, the U.S. sub-prime housing loan market seems like a good bet. But it bears remembering that what may seem crystal clear in retrospect is rarely clear at the time; people caught up in a mania – whether Tokyo real estate of the late 1980s, Bangkok office properties of the mid-nineties, or U.S. home mortgages of the mid 2000s — do not recognize it. When they do, the mania is over, usually with unpleasant results for all concerned.

Second, the IMF’s critical error in the mid nineties lay in what might be termed an educated blindness to the institutional fabric of development. Committed to an ideology that sees the free movement of goods and capital as everywhere and anywhere a good thing, IMF officials forgot that it can be very dangerous to liberalize certain sectors of an economy while others remain closed. (“Forgot” because John Maynard Keynes, whose brainchild the IMF is, would never have made such a mistake – Keynes openly advocated international capital controls.) Asia’s economies were pushed to liberalize their financial systems without, as Giles notes, transparent corporate governance and the institutions of accountable management in place. To be sure, the original pressure on countries such as Korea to open up their financial systems came as much from the U.S. Treasury as the IMF (leaving aside the question of the degree to which the IMF is independent of the U.S. Treasury). One can understand why the United States might insist that it be allowed to sell something at which it is highly competitive – financial services – to countries with which it runs gaping trade deficits. But as the crisis demonstrated, it is very dangerous to remove the means that governments have to steer financial markets in desired directions in countries where informal power alignments rather than law and accounting standards determine corporate control and viability. One may tut-tut all one wants at Indonesia’s powerful Liem family or the Korean chaebol, but forcing these countries to expose their banks to global competition while corporate ownership remained opaque simply set the stage for meltdowns of their respective banking systems.

Japan never made this mistake, which leads to a curious blind spot in Giles’ piece. Giles describes as if it were something new the post-crisis policy response of many Asian countries: export like mad and build up huge reserves of dollars. But this is what Japan has been doing since the 1950s. To be sure, it was only in the late 1960s that Japan emerged with a sufficient cushion of dollars that it could put balance of payments crises behind it. Ever since that time Japan has insulated itself from the vagaries of global markets with its vast accumulations of dollars.

Japan always, however, maintained tight controls over its financial system. Even today, when many of the formal controls have been lifted, no Japanese financial institution would openly defy the Ministry of Finance. The importance of the web of controls was demonstrated in the late 1990s when for a variety of reasons – the Asian financial crisis being one of them – the Japanese banking system came close to meltdown.

It bears remembering that banks do not collapse because their assets – their loans and other investments – deteriorate. They collapse when they cannot raise sufficient deposits to cover those assets; i.e., when their depositors flee. This is what happened in countries such as Thailand, Indonesia, and Korea. But not in Japan; the Japanese authorities kept the system afloat. Their control over the financial system and their vast holdings of dollars enabled them to ride out the crisis.

This is what the rest of Asia saw. Did they learn the “wrong” lessons – i.e., accumulate as many dollars as you can and make sure you have the tools to insulate your financial system if you need to? I suppose it depends on one’s perspective. If one wishes for a world where Americans saved more, where Asian economies were led by buoyant domestic demand and the American government was constrained in its military adventures because it couldn’t borrow the money to pay for them, well, then, perhaps the lessons were “wrong.” But if one is an Asian leader trying to ensure that one’s country can make it through the next global systemic crisis with its independence intact and without a sudden and politically dangerous drop in living standards, maybe they’re not so “wrong” after all.

R. Taggart Murphy is Professor and Vice Chair, MBA Program in International Business, Tsukuba University (Tokyo Campus). He is the author of The Weight of the Yen (Norton, 1996) and, with Akio Mikuni, of Japan’s Policy Trap (Brookings, 2002). He contributed this article to Japan Focus. Posted on August 1, 2007.

On the Asian Financial Crisis see also Walden Bello, All Fall Down: The Asian Financial Crisis, Neoliberalism and Economic Miracles a Decade On.