Introduction by Jean Miyake Downey and Rebecca Dosch-Brow

Chisato (“Kitty”) Dubreuil, an Ainu-Japanese art history comparativist, has charted connections between the arts of the Ainu and those of diverse indigenous peoples of the north Pacific Rim. Currently finishing her PhD dissertation, Dubreuil co-curated, with William Fitzhugh, the director of the Smithsonian Arctic Studies Center, the groundbreaking 1999 Smithsonian exhibition on Ainu culture. Insisting on the inclusion of the work of contemporary Ainu artists, as well as art and artifacts of past Ainu culture, her input redefined the scope of the exhibition and reflected her ongoing activism to challenge the “vanishing people” myth about the Ainu. Dubreuil explains, “We are still here and our culture is still vibrant.”

Dubreuil, with Fitzhugh, co-edited Ainu: Spirit of a Northern People, published by the Smithsonian in 1999, a critically acclaimed volume of interdisciplinary contributions by scholars of Ainu issues. Library Journal described the volume as “the most in-depth treatise available on Ainu prehistory, material culture, and ethnohistory.”

Fig. 1: This is the most comprehensive, interdisciplinary book ever published on the Ainu in English or Japanese. It has 415 pages and over 500 illustrations.

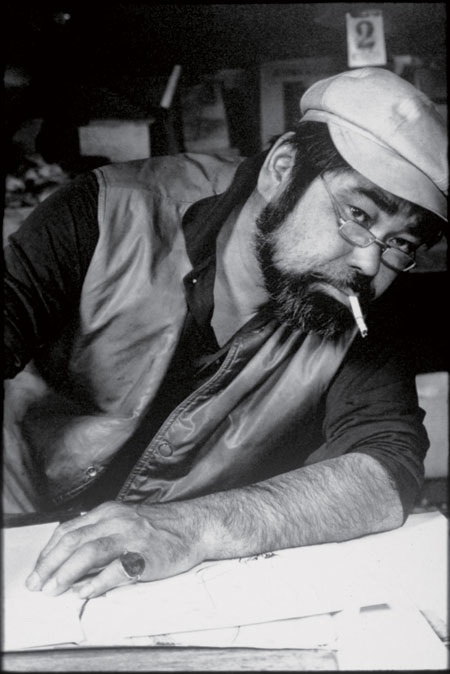

Her second award-winning book, From the Playground of the Gods: The Life and Art of Bikky Sunazawa, introduces the innovative visual artist and Ainu activist who led the “break out” of Ainu art from the tourist market into global fine arts, during a period of worldwide transformations of indigenous arts.Dubreuil’s fascinating account includes details of Sunazawa’s involvement in Japanese avant-garde circles of the 1960’s, when he became friends with originator of Ankoku Butoh, Hijikata Tatsumi, and the famous writers, Shibuzawa Tatsuhiko and Mishima Yukio.Rising to prominence in the 1970’s and 1980’s, Sunazawa helped to develop a powerful and creative reflection on Ainu identity, bridging the Ainu’s rich historical legacies with contemporary political concerns, and drawing inspiration from the work of his mother, one of the most respected textile artists of the twentieth century, and also indigenous art from the Northwest Pacific Coast.

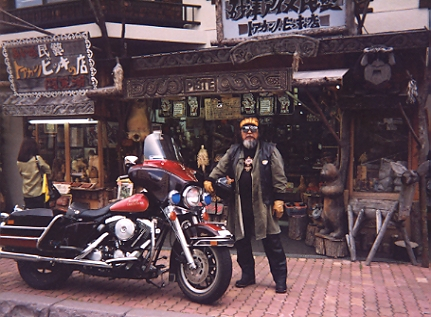

Fig 1 A: Bikky Sunazawa (1931-1989).

Dubreuil has also ventured into literary nonfiction, with an essay paying tribute to Bikky Sunazawa’s mother, Peramonkoro Sunazawa, included in Sky Woman: Indigenous Women Who Have Shaped, Moved or Inspired Us, an anthology of indigenous scholars, artists, writers from across North America, Mexico, Pacific Islands and Japan. It was published in 2005 by Native Women in the Arts, a Canadian organization that promotes the renewal of indigenous cultures.Dubreuil describes the impetus of this work: “The premise of this anthology was to pay honor to specific indigenous women who touched our lives in a special way. I was fortunate to have Peramonkoro as a role model to help me along the way. I suspect my story is different than the other authors in the book in that I never met her. It was through her that I became extremely interested in her son Bikky Sunazawa.”

Fig. 2: The woman in the center is Bikky’s mother, Peramonkoro with his daughter, Chinita, circa. 1965.

A Note to the Reader

The above introduction by Jean Miyake Downey and Rebecca Dosch-Brown was for an interview article entitled “Ainu Art and Culture: A Call for Respect,” that appeared in Kyoto Journal, (no.63, 2006), a widely respected English language journal dedicated to issues in Asia. I am Ainu, and my areas of study are the arts and cultures of the indigenous peoples of the North Pacific Rim.

I was first contacted by Jean Miyake Downey, an attorney dedicated to indigenous rights, in the early fall of 2005 to gauge my interest in a person-to-person interview on Ainu issues.She started our conversation by saying that she had been following my career working on Ainu issues for ten years.My ego properly attended to, I accepted the interview.The interview was to include Rebecca Dosch-Brown who was teaching at the Hokkaido University of Education in Asahikawa, Hokkaido.Asahikawa is the home of the Chikabumi Ainu, and she had developed a great interest in the Chikabumi.

As a setup for the interview and to gather information for the brief introduction, and to identify areas for the interview, Dosch-Brown left the frozen environs of Asahikawa to visit me in the comparatively balmy city of Sapporo.The upshot of the meeting was that Downey was finding a problem getting away from her home in Florida and we would have to do the interview via e-mail. I welcomed the idea for a written interview as it would allow me time to think in greater depth.

The Kyoto Journal gave us a great deal of space for the interview, plus a reprint of my short story, “Her Name is Peramonkoro!” and a review of my book, From the Playground of the Gods: The Life and Art of Bikky Sunazawa. Because so little is known about the Ainu, my inquisitors covered many topics, which required my answers to be more concise than I wished.

Early in 2007 I was contacted by Mark Selden of Japan Focus and asked if I was interested in developing the original article. Knowing that this was a great opportunity, I eagerly accepted.

Because I have published frequently on the Ainu and have given many papers internationally, both Downey and Dosch-Brown had thought my professional life was centered solely on Ainu issues, when actually the majority of my recent academic studies and research have been on the indigenous peoples of the Northwest Coast of Canada and Alaska. Keeping the original questions of Downey and Dosch-Brown, I have expanded my answers dramatically, often comparing the Ainu culture with the Indian cultures of the Northwest Coast. When I first did the interview for Kyoto Journal, we, my husband and I, had recently returned to Hokkaido after an absence of 20 years, and were basically living off the land, a most difficult task during sub-arctic winters. My time in Japan provided an opportunity to see and reflect on the changes of the past twenty years in both the Ainu and Japanese cultures. We subsequently returned to North America in the middle of 2006. Before our move to Hokkaido, we had returned several times to Japan in our search for the perfect bowl of ramen, and for family and research reasons of more then four weeks each, but it simply does not equate to living in the culture. My current free time has allowed me to pick and choose from general project offers. Without a doubt, this reexamination was time well spent.

Chisato O. Dubreuil

**************************************************************************

The Origins of the Ainu and their Culture

JD/RD: The Ainu have been depicted as “mysterious proto-Caucasians” unrelated to Japanese people. However, DNA research shows that Ainu are the direct descendants of the Jomon, the ancient people who created Japan’s first culture and one of the world’s oldest extant potteries. This means that the Ainu and present-day Japanese are biologically related. Would you comment?

KD: The findings were only new to those who wanted to cling to the myth of a lost Caucasian tribe. Some anthropologists have reluctantly supported the theories that came into question because of DNA evidence. True scholarship is open to change, and the advent of DNA research was threatening for some. Other anthropologists knew DNA would revolutionize the field, and were excited by what that might mean. What has been done so far is only the beginning. I don’t think that it is an exaggeration to compare DNA with finding out that the world isn’t flat.

Clearly DNA is the most recent pathway to ‘truth,’ but it’s not the only way to find connections to the past. A few Ainu, including myself, and even fewer freethinking Japanese anthropologists, had already looked at the art of the Jomon as it pertains to the Ainu of long ago. (The word ‘Jomon’ has become an all-inclusive word for early cultures in what is now called Japan; for convenience, I will also use this generic term). When most people think of Jomon, it is their pottery that first comes to mind, especially the highly imaginative vessels with designs made with twined cords. Through research I have found that many of these designs are remarkably similar to traditional Ainu designs. More important to my work are the lesser-known Jomon humanoid clay figurines that featured Ainu style clothing with Ainu-like designs, also placed where they are found on traditional Ainu robes.

Fig. 3: Ceramic figurine found at the Motowanishi site near Muroran, Hokkaido. It has been dated to 700 – 400 BC, from the Final Jomon period.

While DNA evidence makes the Jomon/Ainu relationship clear, the arts of any indigenous group are their visual literature. DNA findings have validated the belief of art historians that the combined age of Ainu/Ainu art makes it one of the longest continuous art traditions in the world. Of course DNA is not the final answer; future study of the history of art and culture must be based on a multi-disciplinary approach. Lastly, the DNA findings throw into dispute the arbitrary assigning of the date of origin of the Ainu as the 14th century BCE. Worse, many archaeologists have put the Okhotsk, Satsumon, and Epi-Jomon cultures in separate categories, even though the art, spiritual beliefs and ceremonies appear the same. More research, especially in the areas of the arts, and more DNA, will, I believe, lead to the reasonable conclusion that there were no cultural disconnects, making the Ainu culture older by more than 10,000 years.

JD/RD: What are some other misconceptions about the Ainu?

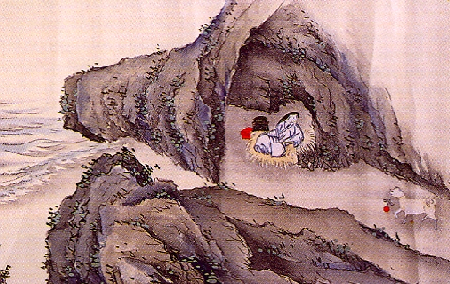

KD: I am always amazed at the number of Japanese who believe in mythological origins of the Ainu, the most prevalent being that we evolved from dogs. If it weren’t so serious it would be

funny. People who are into discrimination will always find reasons to fit their beliefs to their prejudices, however ridiculous the reasons.

Fig. 4: This Ainu-e (literally means paintings of the Ainu by Japanese), was painted by Murakami Shimanojo in Curious Sights of Ezo Island (1799). It depicts one of several origin myths of the Ainu. Japanese children still taunt Ainu children by chanting, “Ainu are dogs.” Children do not think of discriminatory taunts by themselves, they learn from adults.

Another origin myth that is losing credibility is the belief that the Ainu are some kind of lost tribe of Caucasians. The myth was created by early European scholars from the mid-nineteenth century, and because this was a respected view of Europeans, the myth can still be found as fact in some textbooks and reference books. There is some legitimate basis for the ‘mistake.’ The Ainu of the period looked nothing like the Japanese. The Ainu were muscular with skin tones similar to the darker French or Italians. They were very hairy, with thick and wavy hair, luxurious beards, and abundant body hair. Eye color was mostly brown, but could be ‘bluish’ or ‘greenish,’ no doubt a Russian influence. Most importantly, the very young were reported not to have the Mongolian ‘blue’ spot on their lower back. Today, because of intermarriage with the Japanese, the above features are not always present, but I have very thick wavy hair and in the summer I get a very dark tan, my eyes have a more European look, and my body build is somewhat muscular. For all these reasons during my youth I was subject to verbal taunts of “dojin.” While the dictionary meaning is “native,” it is often used as a pejorative term.

Fig. 5: Early visitors to ‘Ainu country’ had reason to question the origin of the Ainu. This picture from the 1860s is of an Ainu mountain hunter from Hokkaido.

One very important misconception is about the bear, the god of the mountains. Some people think that because the bear is ceremonially killed in the “iyomante,” the spirit-sending ceremony, it is a sacrifice to god. IT IS NOT! We believe that the bear IS a god spirit, disguised as a bear (or other living thing), who comes to the people with its gifts of food and fur. The death of the bear releases the spirit, allowing it to return to god’s land. I have been asked about my use of the term “god’s land” as opposed to the most familiar term “the land of the gods”? For us, “god’s land” refers to land belonging to the gods, whereas “land of the gods” suggests a more transient quality. We believe that the use of the term eliminates any ambiguity as to the proprietorship of god’s land.

Fig. 6: Bear ceremonially killed to release its god spirit. To prepare for the journey to god’s land, the bear is given food such as the salmon shown in the foreground. The huge medallion in front is part of a traditional tamasay (necklace) with large glass beads. The necklace identifies the bear as a female. A male bear would be identified with a sword. The sex of the bear has no bearing on matters of any kind.

The spiritual beliefs of the Ainu are complex, they do not fit the usual definition of animism, nor are they a form of Shinto. Kamuy-mosir, the Ainu land of spirits is on a separate track parallel to the human land (Ainu-mosir). There is a different relationship between god spirits and humans. Kamuy (gods) send good or bad gifts to humans depending on how humans treat the gifts of the gods. It is important to understand that we do not worship nature per se. All things in nature are spirits sent to Ainu mosir disguised as bears, trees, wind, etc. There is a big difference between what traditional Ainu believe and those who follow Shino beliefs. Traditionally all Ainu activities were based on respect for the gods. If humans were not respectful, the evil gods (wen-kamuy) would wreak havoc on the people. An easy example; if a village is respectful to kamuy, they would get soft gentle rains for their small gardens, if not, they would be visited by a hundred year flood. Wen-kamuy is very resourceful, and not to be taken lightly. Today most Ainu are Buddhists with a good measure of Ainu belief systems thrown in. There are some Ainu who are Christians, mostly among the Asahikawa Ainu.

JD/RD: The most accepted theory of migration is that the Ainu came from the northern route into Japan. So are the Ainu also a North Pacific people, related to native people from the northern Pacific Rim and adjacent Bering and Chukchi Seas? Do you see evidence of connections reflected in their arts?

KD: I have not seen DNA research comparing Chukchi Eskimo or other peoples of the North Pacific with the Ainu. Given that there has been mutual contact for thousands of years, I am sure that DNA evidence will show that all North Pacific peoples are part of an extended family.

People often ask me if the peoples of the Northwest Coast of the Americas are related.

I strongly believe that we are, but I don’t see what many people consider similarities between Ainu designs, and Northwest Coast carving designs found on house posts, totem poles, or shaman rattles, and designs on ceremonial regalia such as tunics, aprons, leggings and Chilkat blankets. Traditional Northwest Coast designs are not spiritual in the usual sense. Instead, they are mostly signs of social status and ancestral connections, usually related to members from the animal world that became family crests owned exclusively by the individual or family. These ‘rules’ still apply.

The animal itself could represent a spirit. For example, a totem pole is not a ‘religious’ symbol, but the images on it could be, especially with the Tsimshian. This is a new area of research for me. In contrast all Ainu art was made to please the gods (kamuy), but the art could never be made in the image of any of the spiritual gods except for special ceremonial items.

If that’s the case why do we see the ubiquitous Ainu carved bear, the god of the mountains, kimun-kamuy, wherever tourist items are sold? After we lost the wars of the 19th century, the Japanese outlawed fishing and hunting, our main source of food, and many Ainu starved to death. By 1900, our traditional way of life, based on hunting and fishing, was mostly gone. Unique to our beliefs is our relationships with kamuy, if we believe that we have been wronged, we can petition, or even argue with the gods for change. In this case we petitioned the gods through private prayer that we be allowed to change the dogma against making images in the form of gods. We desperately needed to enter the market, and gradually the “Ainu bear” and other animal gods, especially the salmon, kamuy-chep (god’s fish) were carved and offered for sale. Of course, we continue to carve kamuy figures on our most sacred ceremonial item, the ikupasuy, our prayer-sticks, which enable us to communicate directly with the gods.

Fig. 7: The carved bear is the most popular ‘souvenir’ among tourists who travel to Hokkaido. This bear, carved by Ainu artist Matsui Umetaro, is from the 1920s. In 1938 he was chosen to carve a bear for Emperor Hirohito. Unfortunately the overwhelming number of these ‘kanko kuma’ (tourist bears) are not carved by Ainu.

Fig. 8: This sacred ikupasuy (prayer-stick) depicts kimun-kamuy (the god of the mountain) and chep-atte-kamuy (the salmon god). It may have been used for the First Salmon ceremony.

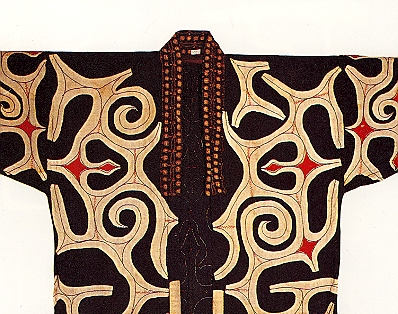

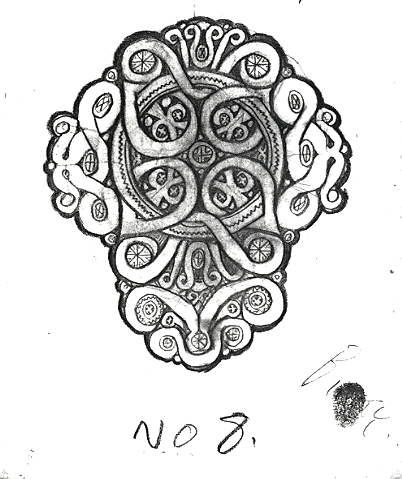

JD/RD: Some people say traditional Ainu designs are so abstract, no one can detect what they represent, while others believe that they see animals such as owls or bears in them. Could you comment further?

KD: Neither is true. First, there isn’t anything to detect in Ainu designs. As stated we believe that the evil gods (wen-kamuy) are so clever that if there was something ‘hidden’ in the design, they would know, and they could enter the image and cause great harm. The beautiful art on the clothes, platters, etc. is our way of honoring and respecting the gods, but the designs are not spiritual in any way. Importantly, tradition dictates that all designs be original. To make a ‘reproduction’ would be disrespectful to kamuy. When looking at a robe, the designs may look the same, but each is different, although admittedly the design differences may be subtle. Part of the problem is the subtle differences between design elements; for example, eight out of the nineteen design elements identified are variations of the whorl.

I do see a possible challenge to design diversity. There are Ainu dance groups that have similar dance robes such as the Asahikawa Chikabumi ‘style,’ the chijiri. They do all look alike, but as I stated, there can be minor differences. I have never had the opportunity to have all robes together to inspect. The designs are too complex to compare individually. Also, it is often reported that all designs on robes are symmetrical. While most are, my research has shown that approximately 15-20 percent are asymmetrical.

Fig. 9: A good example of asymmetrical design. All styles of robes have at least some examples of asymmetrical designs. However, most examples are much more subtle.

Northwest Coast designs are a bit easier to read, sometimes. For example, certain designs such as bears can be identified, but other designs on the bear can be very difficult, for example, frogs coming from the eyes, or wolves on sea bears, both very abstract. More difficult are design elements known collectively as “formline designs.” The known individual elements have been given names such as Ovoid, Tertiary-S, U-form, Split-U, the Salmon-trout’s head, and negative and positive space. Each design element may have countless variations. We don’t know the Native terms for the elements if in fact there were Native terms.

Fig. 10: One side of a contemporary bentwood dish by Tsimshian artist Lyle Wilson. Following the design of a very early dish, “it seems that the greater the masterpiece in Northwest Coast art the less we can say about its meaning” (Wilson Duff, 1983). I believe the simple designs on the Jomon figurine featured in figure 3 are forerunners of modern designs, but could the complex Ainu designs of today come from the spirit world of the Jomon, or from the Northwest Coast, or did the Jomon/Ainu influence the Northwest Coast cultures? We just don’t know.

Historically, other possibilities for east-west artistic influences existed through personal contact or through trade ‘brokers.’ My research reveals oral narratives on both sides of the North Pacific that tell of early contact with each other. Based on interviews of Ainu and Northwest Coast elders from the Tlingit area (now southern Alaska), the Aleutian Islands seem to have been the most logical trans-Pacific route for the Ainu, Aleut and Tlingit peoples. The Aleutian people, neighbors of the Tlingit, certainly traveled east and west, and they no doubt traveled to Kamchatka where the Kamchatka Ainu lived. We know with certainty that the Aleut and Ainu were forced by the Russians to trap sea otter together in the Kuriles in the 1700s, but the big question is, was there earlier contact?

Fig. 11: As this map indicates, the total territory of the Ainu was huge with a much smaller land mass. As maritime traders, they traveled great distances. The fact that there are oral traditions referring to early Tlingit/Ainu contact is exciting.

There is also some physical evidence. An engraved bone needle case was found from the Okhotsk culture (ca. AD 500), with designs very similar to those on early Tlingit Ravenstail robes (ca. 1750-1800). The designs are also similar to the tattoo designs historically found on the backs of hands and forearms of Ainu women. Admittedly the physical evidence is thin, but with more research, we may find new links to the past.

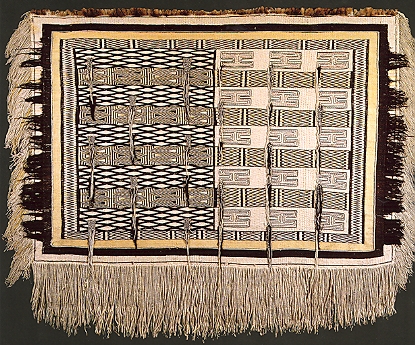

Fig. 12: Needlecases and the needles they contained were very important to the women fashion designers. This Okhotsk case, circa 500 AD, was found in northern Hokkaido. Other needle cases with geometric designs have been found on Shikotan, one of the disputed islands claimed by both Russia and Japan. I have no doubt that other objects from the Kurile islands have similar designs and are in Russian collections.

Fig. 13: The needlecase described in figure 12 has a design similar to those found on Tlingit Raven’s Tail robes. This robe was made circa 1750-1800. Due to climate and weather conditions, older robes are extremely rare with most discoveries being remnants.

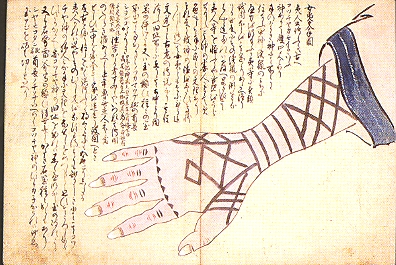

Fig. 14: Tattoos of similar design such as those shown in figures 12 and 13 were common on the backs of hands and forearms of Ainu women well into the first half of the 20th century.

I mentioned oral traditions. Unfortunately, oral narratives in their many forms including but not restricted to stories, songs, and dances, have received little respect. Importantly that is beginning to change among some indigenous groups as shown by the 1997 Supreme Court of Canada decision, Delgamuukw V. British Columbia. In this case the Supreme Court found in favor of the Gitxsan and the Wet’suwet’en tribes in their land claims against British Columbia. The High Court stated that future courts must accept valid Native oral history as evidence, and this will undoubtedly be a key ingredient in future land claim cases. At the time of this writing I am not suggesting that the Gitksan have won the land claims, but their case and future cases must take into account oral histories. The obvious question is how a Canadian ruling affects the Ainu. In the short term probably little, but the ruling is the first on the North Pacific Rim to accept evidence from oral history of an indigenous people, and it could act as a worldwide precedent.

Japan has often responded to international pressure, and now might be the time. The first order of business is to search for any evidence that could support Ainu claims. For example, the eminent Japanese scholar Tanimoto Kazuyuki has been researching the music and dance of Northern Pacific peoples for many years. His research is not based on a specific agenda, but rather seeks to record all these oral histories in dance and song form before they are lost. The late Donald L. Philippi spent years researching traditional yukar (Ainu oral narratives). A fresh look at both his material, and Tanimoto’s, could be especially important as it pertains to legal issues of the Ainu. There is one thing for sure; the Ainu will never cease their fight to reclaim their ancestral lands. I firmly believe that oral histories will aid our peoples. Another thing for sure is that the fight is not going to be easy.

JD/RD: Many people think of not only the Japanese, but also the Ainu as “homogeneous.” Yet haven’t the Ainu always been diverse?

KD: Today when the word “Ainu” is used, many people assume you mean Hokkaido Ainu, and that all Hokkaido Ainu communities are the same. Actually there were Ainu groups in Honshu such as the Tohoku Ainu, but there were also the Sakhalin Ainu, Kurile Ainu, Kamchatka Ainu, and the many Hokkaido groups, some of which either merged with other Ainu groups, or were assimilated in the wajin (Japanese) culture in Hokkaido. The Ainu ‘groups’ were not generic. Besides language differences, there were other differences including ceremonies, fashion, food, housing, dance, and oral histories. Even the major gods are different, depending partly on environmental differences. For example, in all physical environments of the Ainu that can support the bear, the god of the mountain, the bear is the major god. The Kurile Islands, on the other hand, did not have an environment in historical times that supported a bear population. The surrounding waters, however, support a very healthy population of orca whales (killer whales). The killer whale, the god of the ocean, is a major god equal to the bear. Interestingly, the Kurile Ainu, closest to Hokkaido, would occasionally trade for a cub bear for the iyomante, the bear-sending ceremony.

Fig. 15: The Jomon appear to have honored the same spirit animals as the Ainu. Killer whale from the middle Jomon period, 3,000 – 2,000 BC, found at a site in Hakodate, Hokkaido.

Today a very few Ainu claim to be pure blood Ainu. I am certainly not going to argue those claims, but pure blood Ainu would be extremely rare. We have been in social contact with other peoples for thousands of years. The biggest influence initially would have been other Native groups such as the Nivkhi and Orok on Sakhalin Island. The next major influence would have been Russians and later Japanese. Lastly, because the Russians forced the Aleut and the Kurile Ainu to work together harvesting sea otters in the early eighteenth century, there was bound to be genetic exchange.

Fig. 16: Bronislaw Pilsudski, a Polish prisoner of the Russians, took this picture of a wealthy Sakhalin Ainu man around 1905. Identified as a mixed blood Ainu/Russian, the bold designs on his robe, typical of Sakhalin robes, indicate the ready availability of fabrics that the Hokkaido Ainu could never afford. Notice the belt, a clear sign of prosperity. While the Sakhalin Ainu had a separate dialect, they had no problem communicating with Hokkaido Ainu as suggested by the number of intermarriages.

While many cultural differences continue, today some of the biggest differences are political. Unfortunately this has led to a lack of cohesiveness on major issues. Sometimes we are our own worst enemy. This is not only an Ainu problem: I know of no indigenous group that hasn’t experienced the problem of cultural division.

JD/RD: Do you think there are any Ainu left in the areas you mentioned?

KD: Most Japanese scholars believe that there are no “Ainu” in the Kuriles, Kamchatka, or Sakhalin. I totally disagree. There is absolutely no question that there are not only high numbers of mixed blood Ainu/ Russian people, and mixed blood indigenous and Ainu; and there is no doubt that there are at least some Japanese/Ainu in Sakhalin. It defies logic to think otherwise.

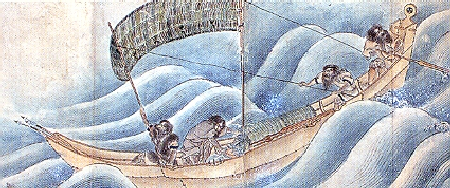

The Ainu, Russians and many ethnic groups were in social contact for centuries. We may never know the extent of Ainu contact, but it’s sure to be considerable. Many people do not know or have forgotten that the Ainu were an entrepreneurial maritime trading people who traveled great distances in the pursuit of business in the Ainu ocean-going canoe, the itaomachip. There are reports that by 1739, and perhaps much earlier, Ainu leaders had some Ainu live among their trading customers to learn their languages and customs to facilitate trade. The people of the North Pacific, not just the Ainu, traveled incredible distances. If the reader has the opportunity to go to New York City, I recommend going to American Museum of Natural History to see the huge Haida Canoe on display. After seeing it, there can be no doubt of long distance travel.

Fig. 17: Maritime travel required a sailing itaomachip (canoe). The trees on any of the Ainu islands were not as big as they are on the Pacific Northwest Coast. Innovation by Native peoples was necessary to compete in the Native maritime economy. To make a ship large enough to conduct business safely, the hull started as a dugout canoe, planks were then split from logs and laced to the hull ‘lapstreak’ style. In 1887, Romyn Hitchcock doing research in Hokkaido for the Smithsonian, measured an itaomachip that was 50 feet long with a 10-foot beam.

JD/RD: Some scholars think that the ancient Kennewick man, whose bones were found in Washington State, was an Ainu. What’s your opinion?

KD: The story of Kennewick Man with its intense legal fighting by several Indian tribes with their ‘allies,’ the affected federal, state, and local government agencies, against the scientists, is so complex, I think a little background is needed. In July 1996, two college students found some human bones on the banks of the Columbia River in Kennewick, Benton County, Washington, which is in the southeastern part of the state. The students led police to the find, and the police called forensic anthropologist James Chatters and took him to the site. Immediately Chatters knew the bones were old, but had no idea how old. Not only were they old, it did not appear that they were the bones of an American Indian. Chatters and a colleague, Catherine MacMillan, a physical anthropologist, were convinced that it was a white person. MacMillan closely examined the skull and other bones and declared that the bones were of a Caucasoid male from forty-five to fifty-five years at death. They had the pelvic bone Cat-scanned and found a stone spear point embedded.

In August samples from the bones were sent to the University of California, Riverside for radiocarbon dating, and the results were astounding! Kennewick Man, as he was now named, was approximately 9,300 years old with a 95 % confidence level. The news of the discovery and its age certainly raised the excitement level in the scientific community, but most especially it raised to a fever pitch the ire of every Indian group in the area, including the Umatilla Indian tribe in Oregon. They believed that Kennewick Man was an Indian, and one of their ancestors. Supporting the Umatilla position were the Army Corps of Engineers, which had oversight of the federal land where the discovery was found. The Umatilla were very unhappy that the bones had been sent to the University of California, Riverside. The Umatilla called the other tribes of their confederation which consisted of the Yakima, the Wanapum band of the Yakima, the Confederate Tribes of the Colvilles, and the Nez Perce, strongly pressured the Army Corps of Engineers, who were working from the Indian perspective, to repatriate Kennewick Man for reburial under the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA). Soon the US Department of Justice and the US Department of the Interior also backed the Umatilla et al. position using NAGPRA.

Immediately the tribes denounced Chatters and his supporters, which now included scientists from the Smithsonian and other academics, accusing them of grave robbing, and holding them liable for violations of the Archeological Resources Protection Act (ARPA). In sum, the tribes wanted to bury Kennewick Man with no scientific research on the bones as quickly as possible. At the same time Smithsonian scientists and several university anthropologists wanted the bones for research without the cumbersome restrictions of NAGPRA. Everyone knew if Kennewick Man were buried with the Umatilla ceremonial rituals, retrieval of the bones for scientific research would be extremely difficult if not possible. Now led by Douglas Owsley from the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, a lawsuit was filed in September 1996, and after two years of intense legal wrangling, the plaintiffs won the right to continue to examine the bones. The strongly worded seventy-six-page judgment from the U. S. District Court in Oregon, came on August 30, 2002. The bones of Kennewick Man are now housed at the Burke Museum on the campus of the University of Washington in Seattle, Washington. Most importantly, the victory established precedent for any discoveries of a similar nature in the future. Cracking NAGPRA was truly unexpected.

It was the early research on the ethnicity of Kennewick Man that was called into question. From the beginning James Chatters and other physical anthropologists strongly believed that the bones were not of an American Indian. The tribes fought back using oral histories on the origin of the Umatilla. Owsley, et al. then used the oral histories against the tribe! The scientists were able to prove the bones were much older than the oral histories of the earliest American Indian in the area, thousands of years older. Clearly the Indian oral histories were the most important part of the scientists’ case. The court agreed with the scientists.

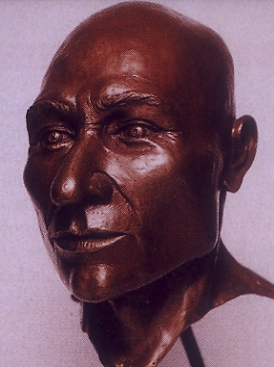

The possible Ainu connection seems to have first surfaced in July of 1996, in a hypothesis brought forth by Richard Jantz from the University of Tennessee. Supporting Jantz was C. Loring Brace of the University of Michigan, who, having seen a picture of Chatters holding Kennewick Man’s skull, believed that the skull was Ainu in appearance. (However, given the age of Kennewick Man, to call it an Ainu would be a misnomer. It should be recognized as having ‘Jomon’ heritage.) Doug Owsley, perhaps the most respected bone scientist in North America agreed that this was a definite possibility, but these scholars also offered other possibilities: that Kennewick Man could be an Easter Islander, Moriori, or a Polynesian. For whatever reason these and other possibilities were rarely mentioned in the press. The possibility that Kennewick Man could be Ainu was advanced by an article in the December 2000 issue of National Geographic, which had a two page spread featuring Kennewick Man. It’s hard to question the top bone man, from one of the best museums in the world, about the quotes in one of America’s most respected magazines. No one said the Kennewick Man was absolutely Ainu, but no other group was mentioned.

Fig. 18: The bust is based on the skull of Kennewick man. Identified as Ainu by some researchers, the skeleton was carbon dated to be 9,300 years old. At that age, the label of ‘Ainu’ is incorrect. To be that old, Kennewick man would be Jomon.

My husband and research partner David interviewed Chatters several times while we were at the Smithsonian. While the age of Kennewick Man is incredible, it is the ethnicity that is extremely important. Could Kennewick Man actually be Ainu/ Jomon? Based on my research, while improbable, I believe it’s certainly possible. If so he most probably came from the Kurile Island Ainu, or from the Kamchatka Ainu. He had the means to reach the Northwest Coast by a large canoe via the Aleutian Islands, a much more probable route than going by the Bering Straits. He could have then traveled south along the coast to what’s now Washington State and then moving upstream on the Columbia River to what is now Kennewick, Washington. Given the location of where Kennewick Man was found, it is interesting to me that no one, on either side of the issue, or the press, questioned where he actually died. He could have died near any river hundreds of miles east and his body carried by waters that emptied into the Columbia. This would be especially true if he died in spring when the rivers were at their swiftest. Of course, it would not have been in the best interest of either litigant to raise the issue, especially the tribes.

Unfortunately, the U.S. government’s actions made DNA identification most difficult if not impossible. For example, after Chatters was forced to give up the bones, some of the bones, under security of the various governments began to disappear. Some were stolen such as most of both femurs, but others were lost or destroyed by government researchers, these include parts of a tibia, a few ribs, and several hand and foot bones. Any loss of bone is inexcusable. There were those who believed that Chatters had stolen the bones, but there was no proof. Chatters and others working with him were pressured by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), and at least one person had to take a lie detector test. Chatters’ later behavior supported his innocence. For two years after the find, Chatters would walk the riverbank where the bones were found. He found more bones and gave them to government officials as required by court order.

Because of the importance of identifying who Kennewick Man ‘was,’ Chatters and others of the Smithsonian team who went to court, pressed the government on the subject of DNA. There are still a great many bones that would have good DNA properties. The fact that DNA testing has not taken place is not a technology problem; the technology needed for extraction of DNA from aged bones has been available for several years. The problem lies with the U.S. government agencies. Not only did the government drag their feet, using a helicopter and a crane they ordered hundreds of tons of rock and soil to be dumped on the site, and immediately planted many fast growing Russian Olive trees. The site was buried! No more Kennewick Man bones were to be discovered!

The question here is why were the various government agencies, including certain parties in the White House, so determined to turn Kennewick Man over to the Umatilla? Why did they ignore the scientific evidence? Why did they make DNA testing impossible? The government knew the age of Kennewick Man was beyond reproach, and that he was not Native American. It is our opinion, if Kennewick Man was proven to be Ainu, or any other non-American Indian, the basis for all ‘Native American’ treaties, would be under assault. The title, Native American, would no longer apply. My husband, part Mohawk and part Huron, believes strongly that all treaties would be in jeopardy, and the ‘Indian fighters,’ the people who are always trying to break Indian treaties, would bring hundreds if not thousands of law suits, legal actions that the Indian tribes would be ill prepared to fight. By claiming Kennewick Man should be under NAGPRA, the status quo would be maintained. Clearly it was in the tribes’ interest to fight for NAGPRA. Even though the problems are incredibly complex, at some point I believe Kennewick Man’s DNA will identify his origin and will be leaked to the public, which will lead to dire consequences. The story is too great to remain a secret.

Aside from the problems facing Native Americans, what if Kennewick Man is Ainu/Jomon, how would it affect today’s Ainu? Immediately interest in the Ainu would multiply a thousand fold around the world, but most especially by the Japanese government. All of a sudden the Ainu would be “National Treasures,” and the Ainu would reign supreme. This puts the Japanese in America very early, and would make for interesting changes in historical understanding. Even more interesting is a question that no one is asking. If Kennewick Man is Ainu/Japanese, is it credible to think he came to North America alone? I believe it would be physically impossible. This is no longer a rhetorical question. While there is a huge time difference, the work of Grant Keddie or George I. Quimby has shown that damaged Japanese ships were blown off course by ocean storms and landing in America and Canada in the early nineteenth century. While this discovery is important, the ‘landings’ were rare, unpredictable events. As I have suggested in earlier publications, I believe the east-west travel by Ainu and Aleuts using the Aleutian Islands as stepping-stones was a common occurrence. In any case, for those of us who believe in early indigenous trans-Pacific travel, it’s an exciting thought.

JD/RD: You insisted that the 1999 Smithsonian exhibition on the Ainu that you co-curated include contemporary art as well as “artifacts.” What does this imply about changes in academic and public discourse on Ainu people and culture?

KD: There are several important museums in Japan that have fine permanent exhibitions of traditional Ainu material culture. My problem with them is that there is no transition of any kind to contemporary work, not even a mention. I believe this is a powerful way to keep the Ainu in the past.

Change is always slow, especially if it is linked to discrimination. A sad example is art. The Japanese art establishment has been steadfast in thinking that Ainu art cannot be viewed as fine art, not even as simple art. There’s even a phrase for it, “craft Ainu.” I can’t believe that anyone who looks at the beautiful traditional abstract designs of Ainu women fashion artists can say it’s not fine art. The rejection of contemporary Ainu art is even more mysterious.

Fig. 19: A fine example of the excellent work by Kaizawa Maki. Her abstract piece “Kamuy Mintar” is, in my opinion, a beautiful work of art. I see her work as a continuation of the evolution of traditional Ainu art.

Before the Ainu exhibition at the Smithsonian, presenting the combination of historical and contemporary art had never occurred, and any exhibition of contemporary ‘craft’ was rare in Japan. It’s my belief that if Ainu art is not allowed to naturally evolve, it supports the Japanese discriminatory position that the Ainu are a backward people incapable of fine art. There was extreme pressure from some Japanese scholars that I not exhibit contemporary Ainu fine art. I asked why? I received no answer. I have given a lot of thought to the question. How could Ainu exhibitions of contemporary art threaten Japan or the Japanese art establishment? I am truly at a loss to come up with an answer.

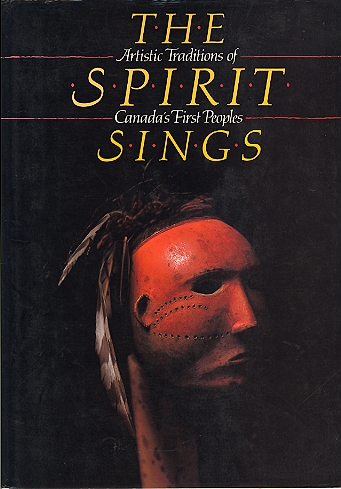

Exhibitions of contemporary Native art in Canada and the States are very popular. Early objects of Native art sell at auction for hundreds of thousands of dollars. Yes, there was a time when there was a lack of respect for Native American art, be it early or contemporary. But if the people and the governments of North America can learn to appreciate and place high value on the arts of Native people, why can’t Japan? Unfortunately, while times change, Japan’s death grip on Ainu culture continues to be unyielding. I know Japanese artists who have no problem recognizing Ainu art for what it is. What is the problem with Japanese scholars and officials?

Unfortunately I think too many Japanese scholars remain stuck in the “sakoku” isolation period (1641-1853) mindset. It was during this period that the Japanese were most aggressive toward the Ainu. I believe there may be a connection. The word, sakoku literally means “country in chains.” Metaphorically, sakoku certainly applies to what happened to the Ainu, their art and culture. I challenge the Japanese to think ‘out-of-the-box,’ and to go beyond keeping the Ainu in the 19th century. I know several Ainu and Japanese, young and old, including myself, who would work toward bringing the Ainu to the twenty-first century world of art. Perhaps the first step would be to work with Bunkacho (the Agency for Cultural Affairs). In Japan the stereotype is always difficult to change. Bunkacho has the prestige and respect to change attitudes.

In North America practically all tourist literature promoting Indians or places where many Indians live, the image of an Indian in traditional dress (i.e. in the Southwest, Oklahoma, or Alaska with totem poles), is designed to make money. These examples have positive elements. An important example is the Santa Fe Railway. The Railway, for over a hundred years, made a fortune using the Southwest Indian image to get people to travel to Santa Fe, New Mexico to have an Indian “experience,” to buy Indian jewelry and pottery, and to see the Old Pueblos. Of course, this image can be hurtful to Indians, but it is better than the images Ainu endure. Interestingly there are images of Native Americans in Hokkaido that are more positive than Ainu images. There is so much the Japanese government could do.

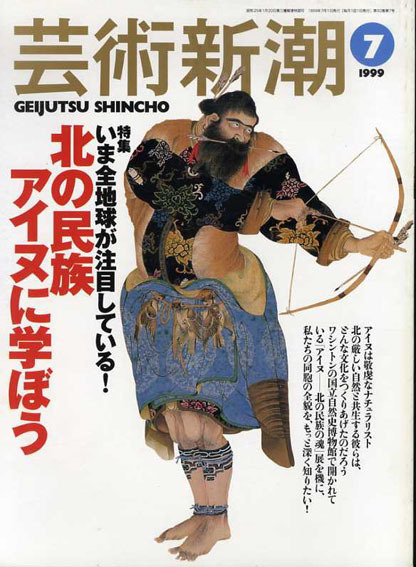

I have often asked myself, was the Smithsonian exhibition a success? I have no doubt that the exhibition was successful but what about in Japan. There were many excellent articles written in Japan such as in the Japan Times, Daily Yomiuri, Geijutsu Shincho, and a great many supportive articles in the Hokkaido Shinbun, which were important, but did it change any behavior? I believe there has been positive change, but currently only at the margins. For example, the Ainu people are now more involved in exhibitions about the Ainu. The Ainu exhibition, “Message from Ainu Craft and Spirit,” organized primarily by Ainu artists and curators, and funded by The Foundation for Research and Promotion of Ainu Culture in 2003, with specific emphasis on the voices of Ainu contemporary artists through their work. Interestingly the exhibition included the abstract work by Bikky Sunazawa which had not been included in Ainu exhibitions in Japan because Bikky’s work was too contemporary. While some Japanese Ainu scholars have categorized his work as “fine art,” this was a very small step considering there is no recognition of the artistic connections between Bikky’s work and traditional Ainu art. Sadly the title of the exhibition still promotes “Ainu Craft” not “Ainu Art.” Hopefully the Smithsonian exhibition has planted seeds for bigger change that will come to fruition at some point in the future.

Fig. 20: The exhibition, “Ainu: Spirit of a Northern People” held at the Smithsonian, received excellent coverage in Japan including major newspapers, and quality magazines such as Geijutsu Shincho shown above. I was even interviewed on Nichiyo Bijutsukan (Sunday Gallery). While this was great exposure, my question for the Japanese media is, where are the positive feature articles today? Must everything positive have to start in a foreign country? A Japanese movie in 2006, Kitano Reinen, was supposed to be a history of Hokkaido. This movie is both an insult and a disgrace. The producers gave a patronizing few minutes to the Ainu. The Japanese built Hokkaido on the backs of Ainu. Where was the story of the theft of Ainu land? The Japanese have much to answer for.

The Ainu Today

JD/RD: Media often still depict the “hairy Ainu” with tattooed faces, in traditional dress, hunting and fishing. Ainu people have changed, but media stereotypes remain. What is a more accurate image of Ainu today?

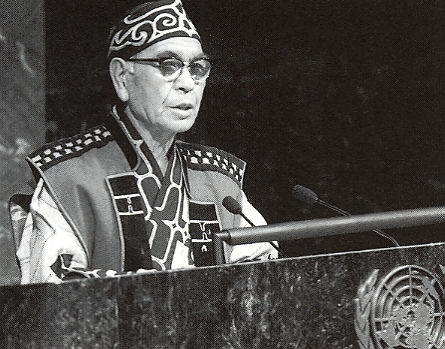

KD: The stereotypical image of tattooed Ainu in traditional dress is still the norm. I believe this is a double-edged sword. There is absolutely nothing wrong with our traditional dress, in fact, traditional dress is a visible political statement saying, “We are still here!”

Fig. 21: American and Canadian Indians have been wearing traditional dress for political reasons in official governmental meetings for over 100 years. It is an identity issue for both the indigenous and the ruling government. The government doesn’t like meeting with indigenous people in traditional dress, but it’s surprising how much more respect is given, if only for the moment. Here we see a meeting in Ottawa in 1969. Notice the drum being played. It is not unusual to start a meeting with a song asking for guidance from the Creator.

But when it’s the only image, it can become negative. However, it is not the image that needs changing; it’s what we do in Japanese society that must change. We are dramatically undereducated. There are no Ainu doctors, architects, anthropologists, engineers, biologists, or aerospace scientists. There are no motivational speakers, and only a few of us speak on Ainu issues.

I have been asked if there are Ainu doctors, architects or biologists who don’t advertise their Ainu heritage. An excellent question, certainly it is possible, but if this is the case, it’s a depressing thought. Why wouldn’t a person say they are Ainu? They don’t have to tattoo “I am Ainu” on their forehead nor do they have to sing and dance to the beat of an Ainu drum. That’s no problem, most Ainu don’t. But if it’s a case of being embarrassed about who they are, or that they will lose social status if they disclose who they are, they become part of the problem! For every Ainu who becomes successful they become a model for other Ainu. As more Ainu become successful, the need for more models lessons. We are looking forward to the day when an Ainu person competes for an important position without prejudice, becomes successful, and no one notices.

Unfortunately, ethnocentricity has always been a staple of Japan’s self-identity.

For example, since the Meiji Restoration the status of Korean residents in Japan has been especially sad. In America they would proudly view themselves as ‘Korean-Americans.’ In Japan they are considered foreigners, and must register with the government as aliens. You are either Japanese, or you’re not! Words like ‘multicultural’ and ‘diversity’ are most often expressed in the context of a proud strength, but these words are not part of the Japanese vocabulary in a meaningful way. If you happen to be born into the majority group it’s great, but if you’re born Ainu, Korean, black, Native American, etc., you will have to pay a social cost.

Fig. 22: Friendship clubs are popular in Japan. Here we see a Japanese friendship club for American Indians. The Indians are from the Blackfoot Nation in the American state of Montana. Interestingly only the Japanese are wearing traditional Indian clothes. I know of no Japanese friendship clubs for the Ainu.

When we only speak to issues and not to accomplishments, we don’t have an issue problem, we have an educational problem. The cruelest of many discriminatory actions is the lack of educational opportunity. This keeps us from gaining self-respect and respect from the Japanese. We can see where we would like to go, but the glass ceiling stops us. In our case, while we live among the Japanese, there are glass walls also. We see our Japanese neighbors taking jobs that are respected. As Ainu we would like to have the same opportunities as our Japanese neighbors. A lack of education is a huge problem. If the Japanese were educated about the Ainu and their issues, maybe, just maybe, both cultures would be winners.

JD/RD: We know official statistics that say there are only 25,000 Ainu people in Japan are disputed. In the past, many Ainu “passed” as mainstream Japanese and hid their Ainu or part-Ainu

ancestry because of discrimination. What does it mean to be Ainu today when all Ainu are of mixed background?

KD: That is a difficult question. The answer will be very different from person to person. Some are extremely proud of being Ainu. I know of a young brother and sister who participated in their college graduation ceremonies dressed in Ainu ceremonial attire made by their mother. Some Ainu have an activist demeanor while others keep their Ainuness a secret, even from their non-Ainu family members.

While it’s impossible to know how many people identify themselves as having an Ainu heritage, there is no doubt whatsoever that there are many more Ainu than the official statistics state. For example, the statistic does not include any Ainu living on any of the Japanese islands other than Hokkaido. It does not include any Ainu living abroad. For example, I am not counted. Even on Hokkaido, many are not included. The statistics published only include the membership of Utari Kyokai (Ainu Association) and many Ainu do not belong. Many Ainu see the Association as a quasi government organization, and a clique that does little for the average Ainu. If people believe the Association isn’t doing what they expect, or what they should do, they must intervene. We Ainu must do more as individuals to improve ourselves.

My husband believes you can’t be proud of something you had no choice in, for example, you can’t select what you’re born as, but if you are indigenous, you can be proud of what you do with your indigenousness. David has worked most of his life to better the lives of Indians, while his brother never tells anyone of his Indian heritage.

JD/RD: Do most Ainu live in the mainstream? Are they pressured to do so? How many Ainu still keep Ainu traditions? Do all Ainu live in Hokkaido?

KD: There is no doubt that all Ainu live in the mainstream Japanese culture. I have never heard of any pressure to enter the mainstream, it just happens. While the Ainu are more “visible” in Hokkaido because of political interaction with the Hokkaido government, as I said above, Ainu live throughout Japan. Of course, being “mainstream” does not mean equal to the Japanese. As to your question asking how many Ainu still keep Ainu traditions; it is impossible to say with any accuracy. However, a great many, perhaps thousands, will have Ainu art, or Ainu craft items in their homes. For example, my mother, who is elderly, has several art works in her home. She has not attended a ceremony in many years.

JD/RD: The Ministry of Education approved mandatory 2006 history textbooks for all schools in Japan, which contain only two brief mentions of Ainu people. How do you, as a scholar, respond to such a silencing?

KD: The Atarashii Rekishi Kyokasho (New History Textbook) for 2006, is an insult to the Ainu, and a huge disservice to the Japanese people. It is a disgrace that most Japanese know more about American Indians than they know about Ainu. Many Ainu, especially, boys, played “cowboys and Indians” as children. I have never heard of Japanese children playing ‘Ainu.’

Today there is much concern about identity theft by criminals, however, when the government commits cultural identity theft on a mass scale, destroying literally everything of Ainu history, there is no challenge. The proof is this officially approved textbook. The entire history of the Ainu in the book consists of a footnote to a discussion on the Okinawans: “On the other hand, the Ainu have lived in Ezo chi (Hokkaido) for a long time, living by hunting, fishing and trade.” Later, in the main text, in a discussion on the Matsumae domain, the Matsumae are described as “controlling the southern area of Ezo-chi, trading with Ainu who made their living by fishing. The Matsumae traded with the Ainu for seafood and fur; the Ainu also traded with the Kurile Islands and Sakhalin Ainu, and the northeast peoples of China who produced what became known as Ezo nishiki silk. The Ainu would then trade the silk to Japan. The Ainu protested unfair trade practices by the Matsumae, and the Ainu leader Shakushain led a hostile action against them.” It is a sad commentary when a people’s entire history is reduced to one hundred and one words.

In this particular case what the text omits is that representatives of the Matsumae called for a halt in the fighting to discuss peace. A meeting was held, and the Matsumae treacherously killed Shakushain and all his men. The total lack of scholarly integrity in this textbook is appalling. But this is just one example, there are many, many more. The Japanese government owes both the Ainu and the Japanese public the truth. While I can understand why the government would want to leave out its disgraceful disregard for Ainu civil rights, the theft of our land, and the continuing lack of respect, I find it mind numbing that the Japanese government can apologize to China for the Nanking massacre, and apologize, if half-heartedly, for their disgusting use of ‘Comfort Women’ during World War II, yet refuse to even discuss their injustices against the Ainu.

JD/RD: American “Indian-fighters” were sent into Hokkaido during the Meiji period to pacify the Ainu. What are the government policy similarities and differences you see between policies toward the Ainu and Native Americans?

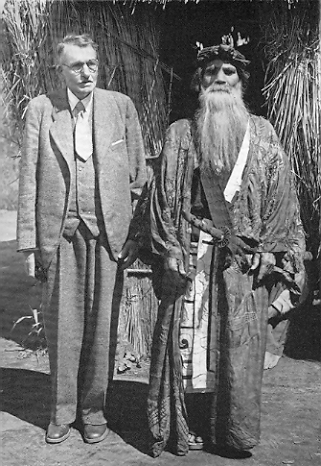

KD: I know of no American “Indian-fighters” who came to Japan during the Meiji Period or any other time. Until recently the Japanese have never thought there was an Ainu problem. During late Edo and early Meiji periods, Ainu were often made slaves or ‘comfort women’. During this time the Ainu were still thought of as sub-human, dogs. When you think of a people in this manner, their social condition is not a concern. The Japanese would see no need for an ‘outside expert.’ It was, and is, as simple as that. If you are in total control, you set the rules, and the Native has no recourse. With that as a given, there is no problem. We were never viewed as equal. There were, however, two important foreigners who did impact Japanese officials, especially Hokkaido officials. They were John Batchelor (1854-1944), an Anglican Church of England lay missionary who came to Hokkaido in 1877, and Dr. Neil Munro (1863-1942), a Scottish physician who lived with the Ainu in Nibutani from 1930 to 1942.

Fig. 23: Dr. Neil Munro with an unidentified Ainu ekashi, a respected elder. The title, “ekashi” is not given to everyone, it tells of a modest person who worked hard for his family and the Ainu people.

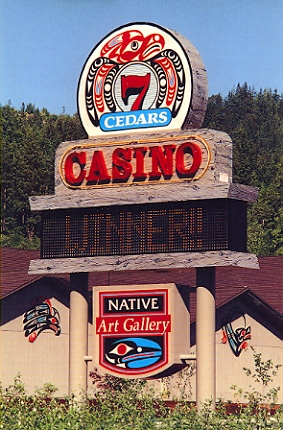

The major differences between the condition of Ainu and American Indians are political and legal. Legally recognized tribes are sovereign governments. The American government knew the land belonged to the Indians, and while this did not stop them from stealing most of it, it was the basis for treaties, many of which included reservations. More importantly, if you were believed to be the lawful owners of the land, you automatically had “legal standing”. This gave American Indians the right to seek redress in the American judicial system. Today legal standing still drives the agenda. For example, Indian tribal governments have the authority to operate gambling casinos, even when the state in which the reservation exists forbids gambling. That’s powerful! Of course, the story of the Indians is much more complex than this.

Fig. 24: An Indian casino can only make a great deal of money if the tribal reservation (the only place where a casino is allowed) is accessible to a much larger population. A tribe in a remote rural area that was extremely poor ten years ago without a casino or other ways to make money, is an extremely poor tribe today.

The problem is not all reservations are in populated or accessible areas that support gambling. Take for example, the Blackfeet Reservation in northern Montana. To simply say that the Blackfeet are in abject poverty is not to understand the situation. Extreme alcoholism, school dropouts, spousal abuse, child abuse, suicides, has translated to an almost total lack of social/educational opportunities. On all roads leading to the reservation there are many white crosses, sometimes with splashes of color from small bouquets of plastic flowers, sad memorials to commemorate the Indians who died at that exact spot. These crosses are the hallmarks of contemporary Blackfeet culture. Spending time there soon leaves you depressed. You ask yourself, is this America? How can the world’s richest nation continue to let this happen?

As bad as these conditions are, legal standing still makes a big difference. The Indians can, and do, sue the American government in court, and they occasionally win! Of course, there are those, including governments, who are devoted to breaking the treaties.

The Japanese and Russians arrogantly believed the Ainu had no rights. When they were able to beat the Ainu at war the winners got everything, while the losers lost everything, even the right to exist as a people. The Ainu have no treaties or reservations, and I know of no area where the Ainu receive treatment comparable to that of the American Indian in terms of rights. There are three areas that they do share to a certain degree: mental abuse, alcohol abuse, and suicide. As stated I believe the incidences of each of these are higher in Indian culture than in mainstream North American culture. Even here there are many programs at the tribal and state levels to help Indians, but welfare is not what is needed.

JD/RD: American Indian renewal has been mainstreamed by a growing number of American Indian scholars, writers, and artists. Are there Ainu Studies programs headed and taught by Ainu people in Japan or elsewhere?

KD: Yes, there are some courses, often with guest speakers who are Ainu. I know of one degree program, the Research Center for Ainu and Pacific Rim Cultures at Tomakomai Komazawa University. I have spoken there and was very impressed with the quality of the students, but when I asked director, Murai Yasuhiro, where the graduates for jobs, he had no answer. Interestingly, there may be more American schools that include Ainu studies as part of their programs at schools such as the University of Alaska, Central Michigan University, and Sterling College in Vermont. On the other hand, partly because of the reservation system, American Indians do have employment opportunities. More important, government and national corporations actively recruit Indians. Education has become a priority for most tribes. About twenty reservations have their own colleges, and most mainstream colleges have scholarships and special programs, including cultural support, for minority students. You can get a doctorate in American Indian studies or Indian art history at several universities such as Cornell, Harvard, University of Washington, and the University of Arizona. In addition to these areas of study, many Natives major in both the social sciences and scientific inquiry, especially in the area of environmental science. Many of these Indians remain on the reservation to work for their people. However, ‘brain drain’ is a problem. For many Indian professionals, there are very few opportunities on the reservations, so they go to where the good paying jobs are. Interestingly, a surprising number of these professionals return to the reservations when they retire. Even with the social problems, the reservations are still home.

Fig. 25: If you were traveling through Indian country in the American Southwest, you would see countless commercial images such as this. Is it appropriation? Of course, but the Native art sold is made by Native artists. The problem in Japan is that you never see similar advertising using Ainu images. The Indian girl is announcing that the business is open, why not an Ainu child? I find this very disturbing.

It is not just American Indians who are advancing. I would be remiss if I did not mention the many educational opportunities the Native people of Canada have. For example, you can get doctoral degrees at many universities, perhaps even more than America. I think it is important to repeat that Canadian aboriginal peoples have also made giant strides in the area of land claims using oral traditions as evidence. While there are many problems in Indian country, the situation of North American Indians is dramatically different from that of the Ainu.

JD/RD: Land rights are another shared issue between the Ainu and indigenous peoples around the world. While the Russians and the Japanese are discussing ownership of the Kurile Islands,

there is a lesser-known debate, among some Ainu people, that the islands should be instead returned to them. Some activists think the new World Heritage site, Shiretoko, should be reserved for Ainu spiritual ceremonies, hunting and fishing traditions. Are these struggles positive or futile?

KD: Political struggles are never a constant march forward. There are ups and downs depending on variables including personalities and events. Activist work on land issues began long before the 1997 Ainu law. The struggle for civil rights, land rights, and respect will continue until we convince the government, with the help of enlightened Japanese, that it is in their best interest to return what is ours. The modern struggle is not a case of being positive or futile, it is our fate, it is our hope. If we do not have hope to act on, we will have lost.

The issues of land theft of the Kurile islands are complex because both Russians and Japanese are involved. Of course the Ainu, victims of this theft, are not party to any negotiations. The Ainu have petitioned the Japanese for possession of at least one of the islands to be held in common for Ainu people should Japan “win.” (A point of clarification – only the four southern most islands of the Kurile chain are in dispute. The rest of the islands belong to the Russians. There are no discussions to return any of these islands to the Ainu.)

Considering that the Japanese have refused to enter into good faith negotiations with the Ainu over any land issue, I am not optimistic about the outcome. Even if the Russians cede the islands to Japan, which is unlikely, we will have to fight for every square meter of land. The likelihood of getting all the islands is unrealistic. To gain even one of the islands, the Ainu have to mount a legal campaign similar to the legal fight of Canada’s Gitksan people as discussed earlier. However, this is easier said than done. To fight legal wars with the Japanese government would require a great deal of money, time and commitment. Where is it going to come from? Who is going to work full time for zero wages? However, I am encouraged by the Gitksan’s victory. With a careful examination of our oral history and recent advances in international aboriginal land claims law, and with the help of those who respect the civil rights of all peoples, I can see a possibility of victory. As I said above, we have to hope, but it takes more than hope, it will take a great deal of work.

Equally unrealistic is the thought that Japan would ever give up Shiretoko. The Japanese government, with some Ainu participation, worked very hard to have Shiretoko made a World Heritage Site. While the Japanese claim was based exclusively on the marine and terrestrial ecosystem of the area of Northeastern Hokkaido (with no reference to Ainu civilization), the people of Hokkaido, both Ainu and Japanese, are excited and proud to have the site.

Revival

JD/RD: Artists such as Peramonkoro used the arts as a way to express and strengthen themselves personally and culturally. What are your thoughts on the role of the arts in Ainu cultural healing and revival, as well as in fostering diversity within Ainu culture?

KD: The arts and spirituality, for many artists, are one and the same. For indigenous people, the arts are more than personal expressions of freedom; they help us to stay in touch with the traditional inner self. The arts are the songs of our soul.

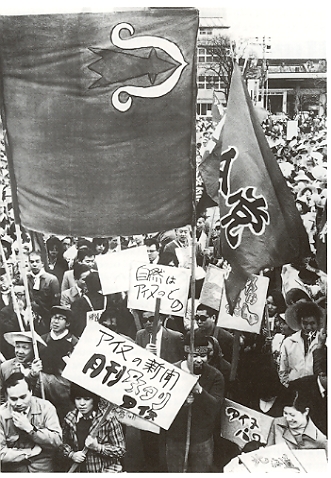

The work of Peramonkoro, and her son Bikky, gave artistic freedom to those Ainu who wanted to go beyond traditional constraints. There is always pressure to remain traditional, but their work gave us the “creative passport” to move forward. Together, they proved that it was possible to treasure tradition while at the same time traveling to the far reaches of our Ainu culture. Change will occur. It must! I believe strongly that indigenous art reflects the cultural health of the people. Bikky, who designed what has become accepted as the Ainu flag, showed us that we must not wait for “permission” to move beyond the mental boundaries forced on us. History is filled with countless indigenous cultures that have died out because, in part, they did not evolve. My research in the arts of the Native people of North America has shown that the more robust Indian cultures have the strongest combination of diverse traditional and contemporary arts.

Fig. 26: Bikky designed the Ainu flag in 1973. While accepted as the Ainu flag, it is rarely seen. Today a new sense of contemporary Ainu pride in part reflects collective dissatisfaction with the Ainu Shinpo (Ainu new law), which keeps the Ainu locked in traditional aspects of being Ainu. Because Bikky refused to be a “kanko Ainu” (tourist Ainu), I think he was saying we should never forget our traditional roots and we must move forward. The design in the flag consists of a red arrowhead (ay) whose color signifies the aconite poison used in hunting, a way of life that was banned by the Japanese. The white contemporary ‘Bikky mon’yo’ (Bikky design) represents the harsh snows of Hokkaido, which Bikky believed made the Ainu strong. Today the flag is occasionally seen at Ainu functions.

Bikky had little patience with Ainu who made being Ainu their only occupation, expecting the Japanese government to support them. Many young artists of today may not understand the legacy that Peramonkoro and Bikky have given us, that being the gift of growth. It’s not an artistic revival that the Ainu need; we have never lost our traditional artistic roots, but we could. We need the vigor of youth to build on those roots to lead us to new heights. But we can’t do it by ourselves. Native Americans and the indigenous people of Canada had the support of non-Natives in their fight for respect for Native art and culture. That respect gradually changed the view that Native art was indeed fine art. In North America the move toward fine art was shared by governments, art lovers, entrepreneurs, and art schools. All the above groups in Japan need to encourage artists to move beyond craft.

JD/RD: Bikky spent a short time on Canada’s Northwest Coast. Was he influenced by Northwest Native art?

KD: There is no doubt Bikky was impressed with the Canadian Northwest Coast art, especially old totem poles, but it was the condition of the Native artists deeply impressed him, above all because they were respected! People wrote books about them and their art because they were respected! Most of all, Bikky was an Ainu artist working among his Native North American peers. He had finally found respect!

Fig. 27: While Bikky finally found self respect in British Columbia, he never lost respect for the Ainu belief system. Upon receiving a log, he would hold a kamuy nomi, a prayer of thanks to the god of the tree, praying for its help in finding the image he was seeking. Ainu believe the object the artist is searching for is in the wood. It is up to the artist to find it. It is difficult to see the ikupasuy (prayer-stick) but Bikky has dipped the ikupasuy in sake, and is sprinkling it on the log.

Proof of this respect was his being invited by the late Haida artist Bill Reid to work in Reid’s studio. Reid, thought by many to be Canada’s most accomplished Native artist, was very impressed with Bikky’s talent and commitment to his art. When I interviewed Reid for my book on Bikky, Reid described Bikky as one who “Looked like a bear, drank like a fish, and worked like a beaver.” Bikky did have a drinking problem but he had an interesting outlook about drinking and art. While he drank moderately during the day, the nights were his biggest problem. When asked why he controlled the drinking the day and not at night? I found his answer most interesting; “I carve during the day, sometimes with power tools. If I got drunk, I could really hurt myself. At night I paint! Nobody gets hurt painting.” Very practical!

Fig. 28: Bikky could carve very delicate works of art, but I believe he really enjoyed attacking his works in the harshest of natural elements. Here he drives his axe through the ice and snow on the log as he seeks the image.

As talented as Bikky was, he had his own problems with self-respect, but as he fought demons, he became a political activist on Ainu issues. Bikky had lived the problems that all Ainu faced. To have self-respect and to be respected is something we all want, whether we are Native or not. I believe that there are more ‘Bikkys’ among our Ainu artists, artists who believe in themselves, artists with the passion to make themselves heard, and artists who are respectful of their traditional artistic roots, but will not be held hostage by them. However, no matter what you feel, you still have to have a chance, someone to believe in you.

It is no secret that I strongly support contemporary art, but not at the expense of traditional art. My research has shown it is ‘inexpensive’ art for the tourist that supports Indian artist’s’ families. This is most often not ‘fine art,’ it’s mostly craft, but the artist who can devote some time to improve his or her art may attain fine art. It is the rare artist that doesn’t begin his or her work in the tourist market, but they do not have to stay there. It is the Ainu people, not just artists, who need to stop listening to the racist remarks that assail us everyday. I know this is not easy, but what are the alternatives?

JDRD: Who are some other Ainu artists and activists?

KD: Without doubt the biggest influences on contemporary Ainu art and/or political activism have been Peramonkoro, her husband Ichitaro, and others such as Hokuto Iboshi, Genjiro Arai, Michi Arai, Kamegoro Ogawa, Tasuke Yamamoto, Shoji Yuki and Giichi Nomura. Unfortunately they have received little credit for their contributions. Without Peramonkoro, Bikky’s art and his activism would have no doubt been much different.

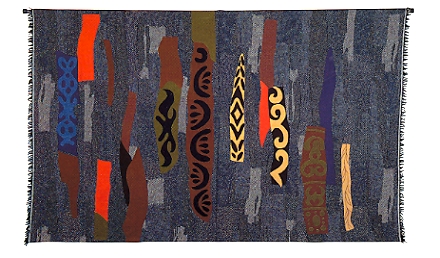

Today Kawamura Noriko continues the legacy that Peramonkoro left us. The art of the Jomon and Ainu have always had an abstract quality to it, and Noriko has taken that abstraction to a higher level. While much of our traditional art was ceremonial, today she produces work to be enjoyed for what it is, fine art. For the Smithsonian exhibition, I asked Noriko to create a large textile image that would represent the main theme of the exhibition, “Kamuy,” our gods, and the spirit of the Ainu. The result was awe-inspiring.

Fig. 29: For the Ainu, god is an abstract concept without human form. I was completely taken by Noriko’s image, it is so positive. Today most Ainu combine Buddhist with many traditional Ainu beliefs.

Fig. 30: This piece was inspired by our sacred prayer-sticks, the ikupasuy. Much of Noriko’s work is quite large, but she does take smaller commissions. This piece, Mokurei (Wooden Spirit) is 300 x 180 cm (10’ x 6’) an average size for her.

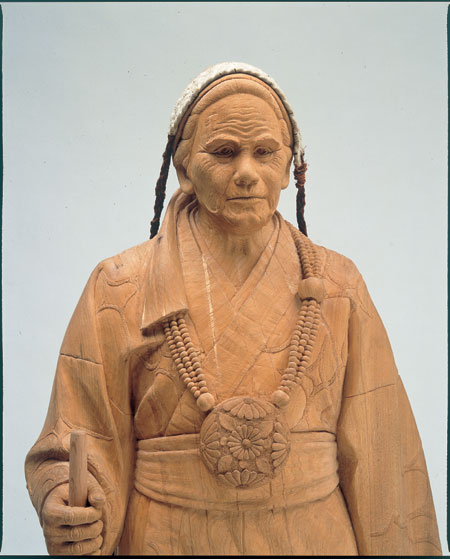

Fine art of another kind is the work of another incredible Ainu artist, Fujito Takeki. His realistic carvings of wildlife are not only breathtaking; they honor the spirits of our gods. He has also honored some of our Ainu elders who helped keep the fires of the Ainu alive during the last century. He immortalized them with life-sized sculptures. He gave each of them his best.

Fig. 31: The wildlife art of Fujito Takeki is truly amazing. He creates all manner of wildlife with equal intensity. An extremely modest man, he sees himself as a simple bear carver.

Fig. 32: Fujito has also honored the elders of the 20th century. This detail is from a life size statue of Fujito’s grandmother, Fujito Take. Words fail me to try to describe his work.

Certainly the most well known Ainu leader and writer is the late Kayano Shigeru. While not politically assertive such as those listed above, he has written more on things traditional than anyone, Ainu or Japanese. His work includes Ainu mythology, a dictionary of the Ainu language (emphasis on the Nibutani Ainu dialect), material culture and a very popular autobiography of his earlier life. In 1994 he entered the national political fray by running for the Japanese Diet, not on an Ainu platform but as a Socialist Party representative for the Nibutani area. He is often credited with being the first Ainu to be elected to the Diet. Actually he came in second in the election only to replace the winner who resigned. He did not win on his own merits.

Bikky Sunazawa and Kayano were good friends. A sign of their mutual respect for each other was Kayano’s use of the colors and symbolism in the Ainu flag that Bikky created, in his lapel pin (lapel pins are very important for Japanese politicians). Lasting only one term, Kayano’s efforts on behalf of the Ainu were basically ignored, and no pro-Ainu legislation was passed. He was deeply disappointed in the lack of achievements on behalf of the Ainu nation, a burden he carried the rest of his life. He was a good and gentle man. His legacy is great, as it should be, but it is sad that the others, the fighters, are not remembered as well.

Fig. 33: Kayano was the last real link to the traditional. I believe this photo captured not only his spirit, but his connection with the gods.

As stated above, Ainu art is held captive to the belief that Ainu art is not art. Unfortunately, it is not just the Japanese who think this way. The Ainu themselves refer to their work as craft. For example, Ainu organizers entitled their excellent 2003-4 traveling exhibition “A Message From The Ainu: Craft and Spirit.” If we don’t believe that we create fine art, we will never change the opinion of others. We must get past the negativity foisted on us.

Things are slowly changing for the better. Prior to the Smithsonian exhibition (1999-2000), Ainu were rarely consulted on Ainu exhibitions of any kind. It was the Japanese who were the curators. At the Smithsonian I argued for unprecedented Ainu participation, and my co-curator, Dr. William W. Fitzhugh, supported me. My husband David, who was project manager, and I traveled six times to Japan over a three-year period. We traveled throughout Hokkaido and Honshu to consult with many hundreds of Ainu. Because of them, many of the fine points of the exhibition plan were changed. For example, I hired Nomoto Masahiro, who is now a curator at the Ainu Museum in Shiraoi, Hokkaido, [www.ainu-museum.or.jp/english/english.html ] to create the major traditional Ainu items, including a “chise” (traditional house), and the itaomachip, the traditional ocean-going canoe. I am Ainu, but I knew nothing about traditional construction of canoes. I wanted authenticity. I knew the chances of anther important exhibition of the Ainu in America may never come again. Nomoto is an Ainu traditionalist, as close as anyone could be in the twenty-first century.

Fig. 34: When developing the Ainu exhibition at the Smithsonian, a large log was needed to make the itaomachip (canoe). Nomoto Masahiro makes the first cut as part of the ceremony to the god of the tree.