Sexual Harassment: The Emergence of Legal Consciousness in Japan and the US

Chika Shinohara and Christopher Uggen

Growing Sekuhara Claims

In 2008, 8,140 women working in Japan brought sexual harassment or sekuhara claims to prefectural equal employment opportunity (EEO) offices. This represents 64% of the 12,782 EEO related reports that women made to regional governments – a large increase since 2005. Sekuhara in fact is the largest discrimination concern reported to EEO offices among employed women in Japan today. These numbers do not simply reflect difficult employment conditions women face, but also provide evidence of growing legal consciousness among working women in response to broader legal and social change. How does such sekuhara consciousness emerge?

Working Women’s EEO-related Claims to Prefectural Governments in Japan (2008)

Source: Ministry of Health, Labour, Welfare, Japan 2008 (http://www.mhlw.go.jp/houdou/2009/05/h0529-2.html)

Ripe for the Development of Sekuhara Consciousness

Our study shows broad similarities in sexual harassment consciousness across working women in Japan and the US, with some notable differences in the rates occurring for different age groups. We compare data from Japan and the US where the employment and life course contexts differ greatly for employed women. Japan, compared to the US, delineates more rigid gender stratification and work-family expectations. Yet, both societies now have laws regulating work harassment. Sex discrimination at work was symbolically banned earlier in both societies. And then, their legal guidelines included specific definitions of “hostile work sexual harassment” and “quid pro quo sexual harassment” in later years. We argue that real and symbolic statements marking sex discrimination as illegal, including the US Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Japanese Equal Employment Opportunity Law (EEOL) of 1985, created conditions ripe for the development of sekuhara consciousness.

Sekuhara Complaints and Results

Harassment complaints appear to be more common when regulatory policy exists, in part because workers make sense of their experiences by referring to legal concepts and categories. This is especially the case for groups such as young women in Japan, who have become increasingly cognizant of women’s employment rights since passage of the EEOL in 1985. We will show our data analysis for the younger age cohort of Japanese working women towards the end of this essay. We first provide recent national statistics on sexual harassment complaints filed with regional EEO offices in Japan and by the EEO Commission (EEOC) and the state and local Fair Employment Practices agencies (FEPAs) in the US. These are not necessarily comparable; however, according to the national data from 2008, in Japan 13,529 (of those, 8,140 by women, 621 by men, 2,378 by employers, 2,390 by others) total cases of sexual harassment were filed, compared to 32,535 cases in the US. Of those in Japan, 364 sexual harassment complaints were filed officially asking support for resolution. Although specific numbers for harassment were not revealed, 70% (473) – of the total resolution- required complaints (676) including sexual harassment (365) as the largest number – reached resolution in Japan. In the case of the US, it is close to 80% (25,910 out of 32,535) that reached some kind of resolution.

Similar History of Law & Media Attention in Japan & the US

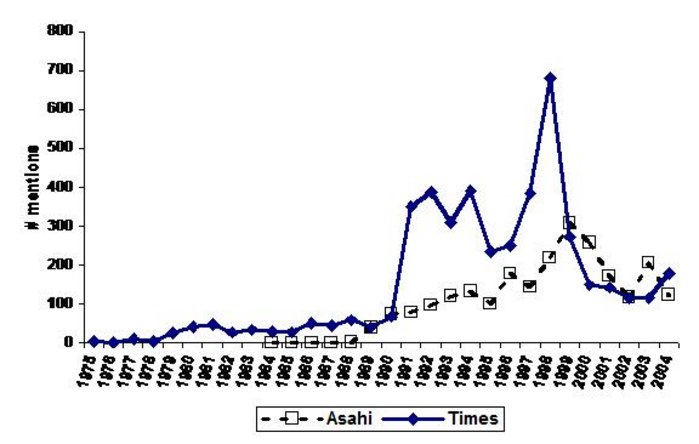

Japanese feminists and legal scholars followed developments of the issue in the US closely, but it was not until 1989 that the popular media coined the term “sekuhara” from the English phrase, sex-ual hara-ssment. Public consciousness of sekuhara in Japan grew after the first EEO legal reform as landmark legal cases were reported. The Fukuoka sexual harassment case (1989-1992), the first successful hostile work sexual harassment case in Japan, accelerated general societal recognition of sexual harassment and women’s employment rights in Japan. Despite the major legal system differences between the two nations, sexual harassment law has developed similarly, albeit on different timetables. As in the US, lawsuits in Japan appeared to spur development of sexual harassment law as part of the EEO policy and its inclusion under the broader rubric of civil rights law. The next chart shows a count of national newspaper articles including the word “sexual harassment” in Japan’s Asahi Shimbun since 1985 and in the New York Times since 1975. We found no mention of either “sekushuaru harasumento (sexual harassment)” or “sekuhara” in Asahi Shimbun Newspaper until 1988.

Newspaper Counts of “Sexual Harassment” in Japan & the US

Sources: New York Times (1975-2004) and Asahi Shimbun

(1985-2004)

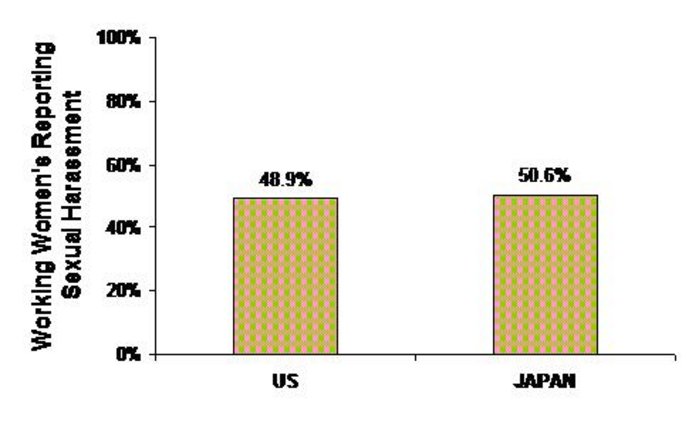

Working Women’s Reporting: Age, Income, & Job Satisfaction

The Japanese Survey on Working Women’s Consciousness (Recruit Works) and the US General Social Survey (NORC) show comparable rates of reported sexual harassment among working women. These are verbal, visual, and physical sexual harassment at work, including stalking and sexual assault in extreme cases. In both countries, about 50% of women in their 20s and 30s report experiencing sexual harassment in their work life. Although reporting rates are alike, younger women and women with higher income levels in Japan reported significantly more lifetime harassment experience, whereas older women reported greater harassment in the US. Such workers in Japan show much lower current job satisfaction rates than their US counterparts. These tell us about the structural challenges responsible for the relationship between work harassment and work (job satisfaction and income). Working women in Japan, particularly highly educated with higher income, have far lower job mobility than do similarly educated women in the US. Such restricted career mobility means they may be stuck in workplaces with their harassers, since women in Japan on career tracks have greater difficulty finding alternative employment.

Women’s Sexual Harassment Reporting in Japan & the US

Sources: Japanese Survey on Working Women’s Consciousness 1992 (N=1562), US General Social Survey 1994 & 1996 (N=642)

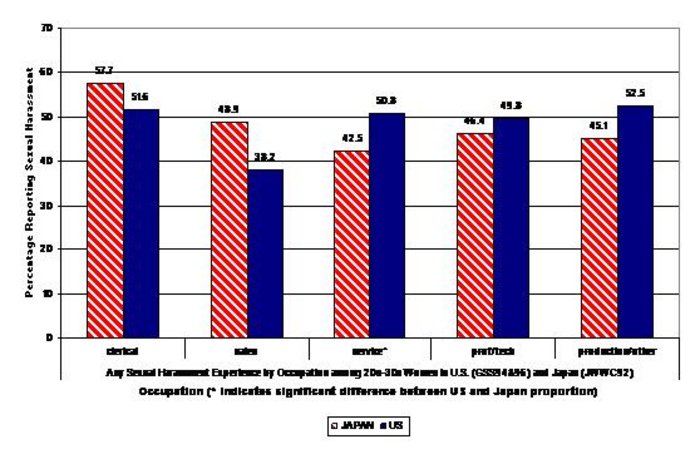

Occupations & Industries Matter to Work Harassment

Although general harassment report levels are similar, worker characteristics differ between the Japanese and American women. Certain occupations and industries show higher work harassment rates than others in both societies, in addition to the income and job satisfaction effects on women’s reporting in Japan. Clerical workers in both societies report higher rates of harassment experience than other types of workers. Similarly, we find significant industry differences of harassment reporting, but again observe little difference between the two countries. Both Japanese and American workers in the manufacturing industry show the highest harassment rates and in the government the lowest. The rate is also quite high in the Japanese finance, insurance, and real estate industries (F.I.R.E.). Overall, the data indicate that women’s work harassment experience reported varies by occupation and industry but show little difference across Japan and the US.

Sexual Harassment by Occupation

Sources: Japanese Working Women’s Consciousness (1992) and US General Social Survey (1994 & 1996)

Sexual Harassment by Industry

Sources: Japanese Working Women’s Consciousness (1992) and US General Social Survey (1994 & 1996)

Note: F.I.R.E.=Finance, Insurance, & Real Estate Industry

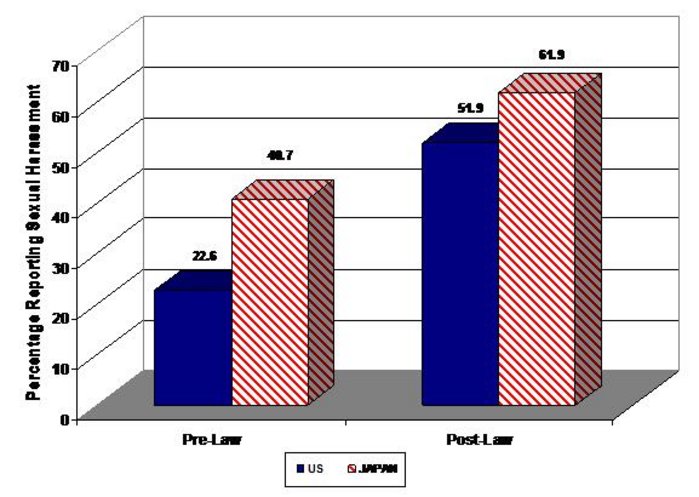

Pre- & Post-Law Cohort Effects on Sekuhara Consciousness

Because sexual harassment came to public attention earlier in the US than in Japan, we predicted differences in sexual harassment reporting across different legal age cohorts in the two nations. We looked at rates before and after major legal changes. . Older women (or the pre-law cohort) came of age before the legal change. Younger women (or the post-law cohort) have experienced the legal change or they came of age after the change. We might expect older working women to report more harassment experience simply because they have worked longer. However, younger women in Japan actually report higher lifetime rates of harassment. The “post-law” cohort reports the highest rate of sexual harassment in both countries (about 62% for Japan vs. 52% for the US). Most notably, the majority of working women in Japan leave their jobs for their family at least for a few years. This reduces the risk of sexual harassment at work. When they return to work, they tend to work lower-skilled jobs for part-time in often gender-segregated workplaces, where they are less subject to harassment. Note that the much lower reporting rate of the pre-law cohort in the US (22.6%) than in Japan (40.7%) is due to the age structure of the available data – the US data (GSS) includes older generations of working women while the Japanese data (JWWC) includes working women in their 20s and 30s only. Older women in both Japan and the US report lower rates of sexual harassment experience.

Sexual Harassment by Cohort

Sources: Japanese Working Women’s Consciousness (1992) and US General Social Survey (1994 & 1996)

Note: US, the pre-law cohort (born prior to 1938) and post-law cohort (1938-1969) Japan, the pre-law cohort (born prior to 1963) and post-law cohort (1963-1967). Japan does not have comparable data from older generations of working women. We omitted the youngest workers from our analysis because their work experience is too short to compare with older workers.

Higher Legal Consciousness among Younger Women

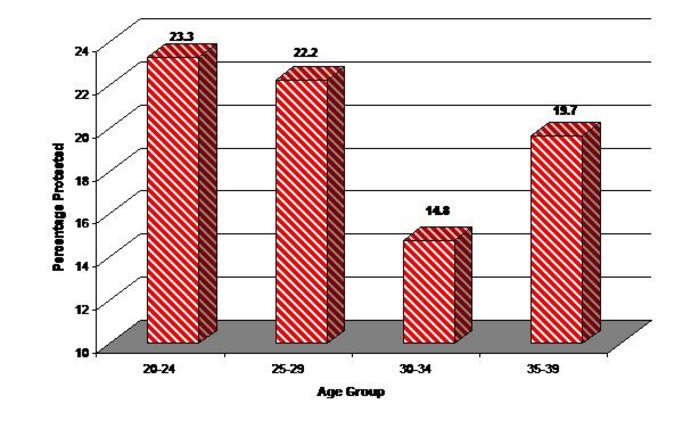

It is difficult to determine from the data whether cohort differences reflect changes in legal consciousness or in rates of actual harassment. If consciousness were changing over time, we would expect differences in these women’s response to harassment as well as in reports of harassment by cohort. The following chart represents this pattern graphically, showing the percentage of women who “strongly protested” when they experienced sexual harassment in Japan. It is important to note, reactions to sexual harassment are also linked to legal options, such that women are more likely to report harassment when they believe there is a mechanism for redress. Women in their 30s show much lower rates of protesting to harassers. A possible reason for this pattern is that they entered the job market before the EEOL implementation – they might not see protesting as their option for changing the situation. Another possible reason for it is that many harassed women in their early 30s are expecting to leave their jobs for marriage and childbearing.

% of Japanese Women Protesting Harassment by Age

Source: Japanese Working Women’s Consciousness (1992)

Sexual Harassment Consciousness in the Life Course

Our results reveal national similarities in work harassment consciousness rather than differences. Nevertheless, comparable rates of self-reported harassment in Japan and the US call attention to the distinctive differences among reporting women in their age, income, job satisfaction, and work types. Our study also identifies differences in sexual harassment on the relation between the employment structure and family life in Japan and the US. In this essay, we showed how the existence of the law increases workers’ legal consciousness or simply “encourages reporting.” Lack of data on work harassment before the inclusion of its definition into the EEOL guideline in Japan do not allow us to speak about the increase or decrease of actual sexual harassment behavior at work. It is possible that violent quid pro quo sexual harassment cases declined for fear of being penalized. Yet, it is highly possible that “hostile work sexual harassment” grows due to the increasing opportunity for male workers to be working with highly skilled women workers. Less talented male workers’ frustrations could be targeted toward their competitors – highly educated female workers. This comparative study on sexual harassment consciousness emphasized the institutional connections between work and family life and the cohort-specific development of legal consciousness.

This article, written for The Asia-Pacific Journal, draws on and extends the analysis of “Sexual Harassment Comes of Age: A Comparative Analysis of the United States and Japan,” The Sociological Quarterly 50(2): 201-234 (2009).

Christopher Uggen is a co-editor of Contexts magazine, Distinguished McKnight Professor, and the Chair of the Department of Sociology at the University of Minnesota.

Chika Shinohara is a Japanese Studies & Sociology Joint Postdoctoral Fellow at the National University of Singapore. This fall, she will start her Assistant Professorship at the Department of Sociology, Momoyama Gakuin University.

Recommended citation: Chika Shinohara and Christopher Uggen, “Sexual Harassment: The Emergence of Legal Consciousness in Japan and the US,” The Asia-Pacific Journal, Vol. 31-2-09, August 3, 2009.